Electrum

Electrumis a naturally occurringalloyofgoldandsilver,[1][2]with trace amounts ofcopperand other metals. Its color ranges from pale to bright yellow, depending on the proportions of gold and silver. It has been produced artificially and is also known as "green gold".[3]

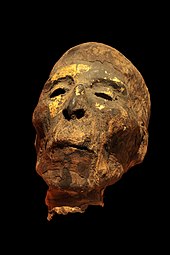

Electrum was used as early as the third millennium BC in theOld Kingdom of Egypt,sometimes as an exterior coating to thepyramidionsatopancient Egyptianpyramidsandobelisks.It was also used in the making of ancientdrinking vessels.The first known metalcoinsmade were of electrum, dating back to the end of the 7th century or the beginning of the 6th century BC.

Etymology[edit]

The nameelectrumis theLatinizedform of theGreekword ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron), mentioned in theOdyssey,referring to a metallic substance consisting ofgoldalloyed withsilver.The same word was also used for the substanceamber,likely because of the pale yellow color of certain varieties.[1]It is from amber’selectrostaticproperties that the modern English wordselectronandelectricityare derived. Electrum was often referred to as "white gold" in ancient times but could be more accurately described as pale gold because it is usually pale yellow or yellowish-white in color. The modern use of the termwhite goldusually concerns gold alloyed with any one or a combination ofnickel,silver,platinumandpalladiumto produce a silver-colored gold.

Composition[edit]

Electrum consists primarily of gold and silver but is sometimes found with traces of platinum, copper and other metals. The name is mostly applied informally to compositions between 20–80% gold and 80–20% silver, but these are strictly called gold or silver depending on the dominant element. Analysis of the composition of electrum in ancient Greek coinage dating from about 600 BC shows that the gold content was about 55.5% in the coinage issued byPhocaea.In the earlyclassical periodthe gold content of electrum ranged from 46% inPhokaiato 43% inMytilene.In later coinage from these areas, dating to 326 BC, the gold content averaged 40% to 41%. In theHellenistic periodelectrum coins with a regularly decreasing proportion of gold were issued by theCarthaginians.In the laterEastern Roman Empirecontrolled fromConstantinoplethe purity of the gold coinage was reduced[quantify][citation needed]

History[edit]

Electrum is mentioned in an account of an expedition sent by PharaohSahureof theFifth Dynasty of Egypt.It is also discussed byPliny the Elderin hisNaturalis Historia.

Early coinage[edit]

The earliest known electrum coins,Lydian coinsandEast Greekcoins found under theTemple of ArtemisatEphesus,are currently dated to the last quarter of the 7th century BC (625–600 BC).[4]Electrum is believed to have been used in coins c. 600 BC inLydiaduring the reign ofAlyattes.[5]

Electrum was much better for coinage than gold, mostly because it was harder and more durable, but also because techniques for refining gold were not widespread at the time. The gold content of naturally occurring electrum in modern western Anatolia ranges from 70% to 90%, in contrast to the 45–55% of gold in electrum used in ancient Lydian coinage of the same geographical area. This suggests that the Lydians had already solved the refining technology for silver and were adding refined silver to the local native electrum some decades before introducing pure silver coins.[6]

In Lydia, electrum was minted into coins weighing 4.7 grams (0.17 oz), each valued at1⁄3stater(meaning "standard" ). Three of these coins—with a weight of about 14.1 grams (0.50 oz)—totaled one stater, about one month's pay for a soldier. To complement the stater, fractions were made: thetrite(third), thehekte(sixth), and so forth, including1⁄24of a stater, and even down to1⁄48and1⁄96of a stater. The1⁄96stater was about 0.14 grams (0.0049 oz) to 0.15 grams (0.0053 oz). Larger denominations, such as a one stater coin, were minted as well.

Because of variation in the composition of electrum, it was difficult to determine the exact worth of each coin. Widespread trading was hampered by this problem, as the intrinsic value of each electrum coin could not be easily determined.[5]This suggests that one reason for the invention of coinage in that area was to increase the profits fromseignioragebyissuing currency with a lower gold contentthan the commonly circulating metal.

These difficulties were eliminated circa 570 BC when theCroeseids,coins of pure gold and silver, were introduced.[5]However, electrum currency remained common until approximately 350 BC. The simplest reason for this was that, because of the gold content, one 14.1 gram stater was worth as much as ten 14.1 gram silver pieces.

-

Electrum coin fromEphesus,620–600 BC

-

Electrum trite ofAlyattes of Lydia,610–560 BC

-

Electrum stater,Carthage,c. 300 BC

See also[edit]

- Corinthian bronze– a highly prized alloy in antiquity that may have contained electrum

- Crown gold- A 22 carat gold alloy highly valued for its use in gold coins from the 16th century onwards

- Hepatizon

- Orichalcum– another distinct metal or alloy mentioned in texts from classical antiquity, later used to refer to brass

- Panchaloha

- Shakudō– a Japanesebillonof gold and copper with a dark blue-purple patina

- Shibuichi– another Japanese alloy known for its patina

- Thokcha– an alloy ofmeteoric ironor "thunderbolt iron" commonly used inTibet

- Tumbaga– a similar material, originating inPre-Columbian America

References[edit]

- ^abChisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 252.

- ^"Coinage".worldhistory.org.

- ^Emsley, John (2003)Nature's building blocks: an A–Z guide to the elements.Oxford University Press.ISBN0198503407.p. 168

- ^Kurke, Leslie (1999).Coins, Bodies, Games, and Gold: The Politics of Meaning in Archaic Greece.Princeton University Press. pp. 6–7.ISBN0691007365.

- ^abcKonuk, Koray (2012)."Asia Minor to the Ionian Revolt".In Metcalf, William E. (ed.).The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage.Oxford University Press. pp. 49–50.ISBN9780199372188.

- ^Cahill, Nick; Kroll, John H.New archaic coin finds at Sardis, AJA 109 (2005).pp. 609–614.