Elena Bacaloglu

Elena (Hélène) Bacaloglu | |

|---|---|

Bacaloglu in 1933 | |

| Born | December 19, 1878 Bucharest |

| Died | 1947 or 1949 (aged 69–71) Bucharest |

| Occupation | journalist, critic, political militant |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Period | 1903–1923 |

| Genre | essay,psychological novel |

| Literary movement | Impressionism |

Elena A. Bacaloglu,also known asBakaloglu,Bacaloglu-Densusianu,Bacaloglu-Densușeanuetc. (FrancizedHélène Bacaloglu;December 19, 1878 – 1947 or 1949), was a Romanian journalist, literary critic, novelist andfascistmilitant. Her career in letters produced an introduction to the work ofMaurice Maeterlinck(1903), several other critical essays, and two novels. She married and divorced writerRadu D. Rosetti,thenOvid Densusianu,theSymbolistpoet and literary theorist.

Bacaloglu lived most of her later life in theKingdom of Italy,where she affiliated with the literary and political circles. Her subsequent work included campaigns forPan-Latinismand Romanianirredentism.This second career peaked upon the close of World War I, when Bacaloglu became involved withItalian fascism.Introduced toBenito MussoliniandBenedetto Croce,she helped transplant fascism on Romanian soil. HerNational Italo-Romanian Cultural and Economic Movementwas a minor and heterodox political party, but managed to earn attention with its advocacy of political violence.

This classical Romanian fascist movement merged into the more powerfulNational Romanian Fascio,then reconstructed itself under Bacalogu's own leadership. It survived the troubles of 1923, but was disbanded by government order in 1925, and was entirely eclipsed by theIron Guard.Shunned by Mussolini, Bacaloglu lived her final decades in relative obscurity, enmeshed in political intrigues. Her fascist ideas were taken up by some in her family, including her brother Sandi and her son Ovid O. Densusianu.

Biography

[edit]Early life and literary debut

[edit]The Bacaloglus, whose name is theTurkishfor "grocer's son" (var.Bakkaloğlu),[1]were a family of social and political importance, descending from theBulgaro-RomanianIon D. H. Bacaloglu, a recipient of theOrder of Saint Stanislaus.[2]Elena's ancestors were first mentioned inBucharestabout 1826, having settled inWallachiaas foreign nationals, and set up business as land speculators.[3]Elena's father was Bucharest civil administrator Alexandru Bacaloglu (1845–1915), related to scientistEmanoil Bacaloglu.He was married to Sofia G. Izvoreanu (1854–1942).[2]Alexandru and Sofia's children, other than Elena, were: Constantin (1871–1942), aUniversity of Iașiphysician; Victor (1872–1945), an engineer, writer and journalist; andGeorge (Gheorghe) Bacaloglu,an artillery officer and literary man.[4]Another brother, lawyer Alexandru "Sandi" Bacaloglu, was less known until a 1923 incident propelled him into the public arena.[5]

Elena was born in Bucharest on December 19, 1878.[6]Compared to other Romanian women of thefin de siècle,and even to some men, she was highly educated, taking her diplomas at theUniversity of BucharestFaculty of Letters and theCollège de France.[7]Her study interests wereFrench culture,art history, and philosophy.[6][8]It was in Paris (where she was chaperoned by Constantin Bacaloglu) that she met Ovid Densusianu, her future lover.[9]However, her first marriage was toRadu D. Rosetti,who was to become a highly successful lawyer and a minorneoromanticpoet.[10]Reportedly, she fell "madly in love", and convinced her reluctant parents to approve of him.[11]They were engaged on December 19, 1896, and had their religious wedding in January of the next year, with politicianNicolae Filipescuas godfather.[12]They had a daughter together.[8][11]

The marriage did not last: by 1897, unable to make ends meet, Rosetti deserted his wife and daughter, who moved back into Alexandru Bacaloglu's home. In June 1898, she attempted suicide by shooting herself in the chest, and was saved by an emergency intervention on her right lung.[11]The Rosetti–Bacaloglu divorce was registered in 1899.[13]On August 7, 1902,[14]Elena married Ovid Densusianu, who was fast becoming the theoretician ofRomanian Symbolism.Historian Lucian Nastasă describes theirs as an odd union. Elena was "extremely beautiful"; Ovid, much less educated than his wife, was also "short and limp".[15]They had a son, Ovid Jr (or Ovid O. Densusianu), born in March or April 1904.[16][17]

Bacaloglu's editorial debut was in 1903, whenEditura Socecpublished her monographDespre simbolizm și Maeterlinck( "On Symbolism and Maeterlinck" ).[18]Together with the essays ofAlexandru Bibescu(1893) andIzabela Sadoveanu-Evan(1908), it constitutes an early Romanian attempt to define the limits of Symbolism,Decadenceand modernity. In Bacaloglu's interpretation, Symbolism and Decadentism were the two sides of a coin: while the Decadents gave voice to the late-19th-century "degeneration" of theLatin race,the Symbolists epitomized the Latin "revival", a triumph of mysteries and metaphysics. Straddling these two eras were Maeterlinck'sHothouses,which she was the first to discuss from a Romanian perspective.[19]According to literary historianAngelo Mitchievici,Despre simbolizmtackles the literary critic's perspective as a "participatory-impressionisticformula, not lacking in refinement ".[20]

In 1906, Bacaloglu also published herpsychological novel,În luptă( "In Combat" ), followed in 1908 by another novelistic work,Două torțe( "Two Torches" ).[21]Her writing was poorly reviewed by the literary chronicler atViața Românească,who argued thatÎn luptăwas impossible to read through.[22]The book was presented to theRomanian Academyas a candidate for the annual literary prize, but was rejected with objections regarding Bacaloglu's "tortured" writing technique and her poor grasp of literary Romanian.[23]Other magazines, includingNoua Revistă Română[24]andConvorbiri Critice,[25]hosted samples of her literary work.

Relocation to Italy

[edit]Meanwhile, Bacaloglu had separated from Densusianu, divorcing him in 1904.[26]Having traveled through much of Western Europe,[6]she spent most of her time in Italy, writing articles forIl Giornale d'Italia,Madame,and the political magazineL'Idea Nazionale.[27]For a few months in 1908, she had an affair with the poet-playwrightSalvatore Di Giacomo,whoseAssunta Spinashe translated forConvorbiri Critice(August 1909).[27]She later married a third time, to an Italian.[28]

In the early 1910s, Bacaloglu was living in Rome, where, in September 1912, she published a monograph about the love affair between Romanian poetGheorghe Asachiand his Italian muse, Bianca Milesi.[29]A recipient of theBene Merentimedal, granted by theRomanian KingCarol I,[30]she translated into French the prose work of his consort,Carmen Sylva.[31]She also represented Romania at theCastel Sant'AngeloNational Exhibit, and, as "Hélène Bacaloglu", gave French-language conferences about Di Giacomo. During the period, she came into conflict with Romanian antiquarianAlexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș.Mandated by the Romanian government, Tzigara replaced Bacaloglu at the National Exhibit's Romanian Committee. He described Bacaloglu as an illegitimate, self-appointed, representative, and noted that the Italian press also mistrusted her abilities.[32]Bacaloglu presented her own version of the events in a protest to the curators, later published as a brochure.[33]

Her conferences on Di Giacomo were received with more sympathy: Alberto Cappelletti gave them a good review inIl Giorno,and E. Console republished them as a fascicle, but all such collaborations ended abruptly when her collaborators became dissatisfied with her character and the quality of her prose.[34]She still continued to be held in esteem by her Romanian peers and, in 1912, was voted into theirRomanian Writers' Society.[13]

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, Bacaloglu turned to political activism andinterventionism,campaigning for still-neutral Romania to join theEntente Powers,and supporting the annexation of Romanian-inhabitedTransylvania.To this goal, she published in Bucharest the Italian-language essayPer la Grande Rumania( "ForGreater Romania") and the French-languagePreuves d'amour. Conférences patriotiques( "Proofs of Love. Patriotic Conferences" ).[21]In Bacaloglu's activity, irredentism blended with the cause ofPan-Latinism.She joined the Pan-Latin associationLatina Gens,which welcomed in members of all "Latin"nations and looked forward to a" Latin federation "of states.[35]Working for this organization, she became close to Italian GeneralLuigi Cadorna,described by Romanian officials as her "protector",[36]andForeign MinisterSidney Sonnino.[30]

Her efforts to popularize the Romanian cause among the troops fighting on thenorthern Italian frontwere interrupted in October 1917 by theBattle of Caporetto,which Italy lost, forcing Bacaloglu to take refuge inGenoa.[36]She subsequently played a part in creating the "Romanian Legion in Italy". Grouping Romanians from Transylvania and Italian sympathizers, this military formation fought theCentral Powersin Italy. However, Bacalogu andLatina Genswere not invited at the Legion's founding ceremony, held atCittaducalein June 1918.[37]

According toVictor Babeș,the Transylvanian doctor and publicist, Elena Bacaloglu was "the great propagandist of Romanianism abroad, and especially so in Italy".[38]The cause of "Greater Romania" fascinated two of Bacaloglu's three brothers: Victor, the author of patriotic plays,[39]created one of the first all-Romanian newspapers inBessarabia;George fought with distinction during thewar of 1916,fulfilled several diplomatic missions, and was later aPrefectofBihor County,Transylvania.[40]Elena, Constantin and Victor were all correspondents for George Bacaloglu's cultural review,Cele Trei Crișuri,well into the 1930s.[41]

Fascist experiment

[edit]After the war, Elena Bacaloglu remained in Italy as a correspondent ofUniversul,the Bucharest daily.[42]One of the first Romanians to gain familiarity with the modern far-right movements in Europe, and, historians assess, driven by an "enormous ambition",[43]she contemplated transplantingItalian fascisminto Greater Romania. This project had preoccupied her since the "red biennium"of 1919–1920, when she presented aproto-fascistappeal to the Italian nationalistGabriele d'Annunzio[44]and wrote articles forIl Popolo d'Italia.[45]Benito Mussolini,who presided over theFasci Italianiparamilitaries, also received Bacologlu's letters, but was noticeably skeptical at first.[44]She also addressed Italian journalistsGiuseppe BottaiandPiero Bolzon,who agreed to become members of Bacaloglu's Romanian fascist steering committee.[44]At the time, Bacaloglu was also a friend of philosopher and fascist admirerBenedetto Croce,and corresponded with him on a regular basis.[13]

Just as she was embarking on this ideological mission, Bacaloglu was drawn into a conflict with the Romanian political establishment. In theItalian Chamber of Deputies,Mussolini'sNational Fascist Partytook up her cause: in August 1920, deputyLuigi Federzoniaccused the Romanian state of trying to kidnap and silence Bacaloglu, "a person of the highest respectability".[46]In 1922, the tribunal ofCasale Monferratoheard her complaint against Romania over copyright issues.[36]Bacaloglu again complained that RomanianSiguranțaagents tried to kidnap her during theGenoa Conference.[36]The same year, fascist deputyAlessandro Dudantook Bacaloglu's side in her conflict with Romanian authorities, noting that the latter were abusing their powers.[36]Bacaloglu and her claims were shunned by successiveRomanian Ambassadors,who simply noted that she suffered from a "mania for persecution".[30]

Mussolini himself acknowledged Bacaloglu's admiration. He corresponded with Bacaloglu, sending her point-by-point instructions about "Latin expansionism" and about economic cooperation againstcapitalism.These were made public by Bacaloglu in her brochureMovimento nazionale fascista italo-romeno. Creazione e governo( "National Italo-Romanian Fascist Movement. Creation and Steering" ), published in Milan after Mussolini's victorious "March on Rome".[47]Seeking to "draw the fascist chief [Mussolini] closer to Romania's political course",[48]Bacaloglu also made visible efforts to prevent a rapprochement between Italy and Romania's rival,Regency Hungary.[30]She denounced Romania's foreign policies in articles she wrote for the Italian newspapers, depicting liberal politicians as lackeys of theFrench Republic.[49]

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism inRomania |

|---|

|

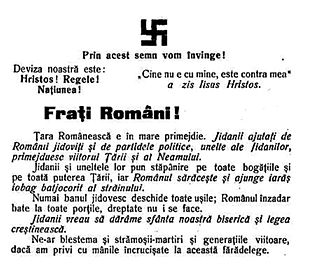

At some point in 1921, with Mussolini's acquiescence, Bacaloglu established an Italo–Romanian fascist association, later known asNational Italo-Romanian Cultural and Economic Movement(MNFIR).[50]Her followers began setting up fascist leagues in Romania—one of the first such clubs was founded in the Transylvanian regional capital,Cluj.[51]The main difference between the Italian and Romanian fascists was their respective stance on the "Jewish Question":the Italo-Romanian Movement wasantisemitic;the originalFasciwere not.[52]The goal was supported by other Constantin Bacaloglu, in his work at Iași University. Working with the antisemitic opinion leader,A. C. Cuza,he gave endorsement to rioters who called for the expulsion of mostRomanian Jewishstudents, and tolerated fascist symbolism.[53]However, according to political scientist Emanuela Costantini, the antisemitic agenda of the Movement was comparatively "moderate"; she highlights instead Bacaloglu's other ideas: "ananti-industrialismin thepopulistmold ", and a version of nationalism heavily inspired by theAction Française.[54]

The Romanian branch of Italian fascism was always minor, and vied for attention with a plethora of paramilitary groups. As suggested by Costantini, it shared theiranticommunismand contempt for democracy, but was the only one to be directly inspired by Mussolini.[55]In 1922, MNFIR split, and its more powerful sections, presided upon byTitus Panaitescu Vifor,[52]merged with theNational Romanian Fascio(FNR).[56]However, in 1923, Bacaloglu reentered central politics as leader of the reconstructed MNFIR, directly modeled on theFasci Italiani.[57]On December 30 of that year, she founded the propaganda weeklyMișcarea Națională Fascistă,of which she was also the "political director".[58]Only about a hundred people were persuaded to join,[59]even though, as historian Francisco Veiga notes, many represented the more active strata of Romanian society (soldiers, students).[52]Powerful cells gravitated around theUniversity of Cluj(Transylvania)[60]and Constantin Bacaloglu's own Iași University.[61]Women themselves were largely absent: still not granted the vote under the1923 Constitution,they generally preferred enrollment in specificallyfeministorganizations, and were never popular with the more significant Romanian fascist parties (including, from 1927, theIron Guard).[62]

Antifascist clampdown and disgrace

[edit]Throughout its short existence, Bacaloglu's association was very vocal in condemning the Romanian status-quo and theTreaty of Versailles.She believed that theLittle Entente,which was partly dedicated to counteringItalian irredentismbut included Romania, would leave the two countries prey to capitalist and Jewish exploitation.[63]Some reports suggest that the "Romanian fascio" took it upon itself to threaten enemies of the deposed, but politically ambitious,Crown Prince Carol(who did not in fact approve of the Romanian fascists).[64]In October 1923,Nicolae Iorga,a historian who opposed Carol's return, accused the organization of sending himhate mail.[64]

The MNFIR became the object of government repression, soon after the antisemitic studentCorneliu Zelea Codreanuwas arrested on charges of terrorism. Codreanu had attempted to assassinate the staff ofAdevărul,including the Jewish managerIacob Rosenthal,and, during the interrogations, implicated other fascist alliances. His testimony was disputed byVestul României,the pro-fascist newspaper ofTimișoara,which claimed: "The attempt [...] is not the work of terrorists, as was quickly proclaimed by some of our colleagues, but the mere revenge of one Sandi Bacaloglu who wished to defend the honor of his sister, that had been compromised by oneAdevărularticle, wherein it had been claimed that Elena Bacaloglu had been convicted for immodesty by the appellate court of Genoa. "[65]Several other theories circulate regarding Codreanu's motivation, but it is known that his group of assassins included an FNR man, Teodosie Popescu, and also that the act was celebrated in the FNR media.[66]

The news was taken up in another Transylvanian paper,Clujul,which claimed that "the lawyer Bacaloglu" had "taken revenge on his sister's slanderer".[67]Also according toClujul,Vifor, who lived in Rome and was not involved in the Rosenthal incident, remained recognized as the "fascist leader" —as FNR president. Meanwhile, George Bacaloglu, interviewed by the press, denied any connection with his sister's movement.[68]According to historian Armin Heinen, the MNFIR was never a fully fledged party, whereas Vifor's more powerful movement could present a more attractive platform to some of Bacaloglu's disillusioned followers.[69]The FNR was explicitlyNazias well ascorporatist,and as such still had little to do with the Mussolinian program.[70]Somewhat larger in numbers, it managed to absorb two other nationalist political clubs, emerging from this fusion with a program supporting dictatorial politics and the expulsion of all foreigners.[71]

Sandi Bacaloglu was soon imprisoned, facing charges of attempted assassination and sedition.[72]The court only cleared him of the more serious charges, and fined him 50Lei.[73]Accounts differ as to what became of Elena Bacaloglu's fascist party. She is credited as a founder of the successorNational Fascist Movement(MNF), closed down byRomanian Policein 1925.[74]However, this mainly Transylvanian party did not have a direct link with the Bacaloglus. Before the police clampdown, the FNR announced inClujulits goal of destroying "the intrigues of foreigners", and its motto ( "The Fascio does not forget!" ).[75]It also informed Transylvanians that Sandi Bacaloglu, recently freed and presenting himself as a Mussolini envoy, was not a fascist, and could not claim to represent any local fascist party.[75]

Bacaloglu became apersona non grataand was deported from Italy once Mussolini grew aware of her dissident stance.[76]A Romanian police report of the period suggests that "the Fascist Party of Romania" intended to join up with Cuza and Codreanu'sNational-Christian Defense League(LANC) and theRomanian Action,into a "National Christian Party".[77]In October 1925, however, Cuza officially announced that the National Romanian Fascio, the Romanian Action, and the Transylvanian Social-Christian Party had voted to dissolve and merge with the League, with the common goal being "the elimination of the kikes". Sandi Bacaloglu signed his name to the appeal as a Fascio representative, and became a member of the LANC's executive council, on par withIoan Moța,Ion Zelea Codreanu,Iuliu Hațieganu,Valeriu Pop,Iuniu Lecca.[78]Afterward, Sandi Bacaloglu ran in thegeneral election of 1926on the same list as Cuza and Codreanu.[79]

In 1927, his sister still held claim to being leader of "the national fascist movement", with temporary headquarters in "the Solacoglu House",Moșilor.[80]She also pursued her dispute with the Romanian state. She claimed that the authorities still owed her some 4 million Lei, which she tried to obtain fromInterior Affairs MinisterOctavian Gogaand from Writers' Society presidentLiviu Rebreanu.In her letters to Rebreanu, she made transparent allusions to the possibility of mutual help but, researcher Andrei Moldovan suggests, was incoherent and needlessly haughty.[81]

Later years

[edit]In 1928, Bacaloglu left Romania on a visit to theKingdom of Spain,where she continued to campaign for Pan-Latinism and collaborated withLa Gaceta Literaria.[31]The latter introduced her as "that Central European feminine type, dedicated to journalism, to embassy work, to zigzagging and daring missions."[31]For his part, Vifor had probably put his activity on hold by January 1929, when he was assigned a diplomatic post inBarcelona.[82]He later returned to Bucharest as a representative of Balcan Oriente news agency.[83]Also in 1929, the Romanian fascio was revived a third and final time, when a certain Colonel August Stoica tried to use it in his coup against government, variously described as an "operatic plot"[52]or a "shambolic conspiracy".[84]The conspirators were rounded up and made subject to a public trial, during which prosecution invoked theMârzescu Lawagainst fascist as well as communist sedition.[85]

Bacaloglu herself remained active on the margin of Romanian politics, witnessing from the side as Prince Carol retook his throne with the help ofIuliu Maniuand theNational Peasants' Party.She approached the Maniu government and theForeign Ministrywith offers of support and complaints about past persecutions, but these were poorly received.[8]She was eventually allowed to return to Italy in support of the Romanian propaganda effort, protected by the National Peasantist undersecretary,Savel Rădulescu(and, allegedly, by theLeague of Nations'Nicolae Titulescu), but lost endorsement in a subsequent transfer of power.[86]She continued with her appeals to Rebreanu (who was also being asked to help George Bacaloglu reviveCele Trei Crișuri)[87]and writer-bureaucratEugen Filotti.In 1931, she claimed that a conspiracy, headed by diplomatFilip Lahovaryand the leaders of theNational Liberal Party,wanted to assassinate her "through hunger" and prevented her from even talking to people of influence.[88]Bacaloglu also stated that, in exchange for recognition of financial support, she could obtain Mussolini's endorsement for the National Peasantists, who were in the opposition.[88]

Sandi Bacaloglu carried on a LANC activist and then joined the successorNational Christian Party(PNC), running in thelegislative election of 1937in Bucharest'sBlack Sector.[89]As a Bucharest PNC leader, he also led street battles with a more minor LANC splinter group, the Fire Swastika.[90]By then, Elena's son by Densusianu was also entering public life. Educated in Italy and Romania, Ovid Jr trained as a schoolteacher[17]and then became a press officer at the Interior Ministry.[91]He also had prospects of becoming a writer, and is especially remembered for a 1937 novel,Stăpânul( "The Master" ).[92]He adhered to his mother and uncle's fascist ideology: he was a staff writer for the Iron Guard paperPorunca Vremii,translated the political essays of Mussolini andAntonio Beltramelli,and campaigned in support of Italy during theEthiopian War.[17]In May 1936, he helpedMihail Manoilescuestablish the local network ofFascist Action Committees(CAUR).[93]

Always a staunch critic of fascism,[94]Ovid Densusianu Sr died unexpectedly on June 8, 1938, after surgery andsepsis.[95]A year into World War II, Elena was again living in Rome, but had to return to Romania because, as she put it, "fake Latin nationalists" wanted her gone.[8]She was issued new papers attesting her move to Bucharest, and was still living there in April 1945.[96]During the same interval, Titus Vifor reactivated his fascism. He was assigned by the Iron Guard's "National Legionary State"to direct the Romanian Propaganda Office in Rome, together with writersAron CotrușandVintilă Horia,[97]and, in May 1941, became its president.[83]

In old age, Bacaloglu witnessed theAugust 1944 Coup,Soviet occupation,and the transition from fascism to democracy, then to communism. In 1947 she sold the letters she had received from Italian literati to the publicistI. E. Torouțiu,who passed them on to theRomanian Academy Library.[8][30]She maintained friendly contacts with the left-leaning writerGala Galaction,but nevertheless lived to see the effects of political retaliation and recession on the Bacaloglu family: her daughter by Rosetti was sacked from her government job.[8]

Bacaloglu died later that year (or, according to some sources, in 1949),[98]and was buried inBellu cemetery.[2]She was survived by Ovid Jr. After the official establishment ofCommunist Romania,he focused on his work as a philologist, but was still arrested in 1958, and spent six years as a political prisoner.[17]He died in Bucharest, on April 19, 1985.[17]

Notes

[edit]- ^Alexandru Graur,Nume de persoane,Editura științifică,Bucharest, 1965, p.31.OCLC3662349

- ^abcGheorghe G. Bezviconi,Necropola Capitalei,Nicolae Iorga Institute of History,Bucharest, 1972, p.58

- ^George Potra,Documente privitoare la istoria orașului București (1800–1848),Editura Academiei,Bucharest, 1975, p.38, 247–248, 325–326, 525–526

- ^Babeș, p.12. Vital dates in Onofreiet al.,p.239, 242

- ^Vestul României,Nr. 32/1923, p.3, 4

- ^abcCalangiuet al.,p.xxi

- ^Nastasă (2010), p.51, 117, 133–134, 310. See also Calangiuet al.,p.xxi

- ^abcdef(in Romanian)Nicolae Scurtu,"Note despre prozatoarea Elena Bacaloglu"Archived2015-06-24 at theWayback Machine,inRomânia Literară,Nr. 22/2015

- ^Nastasă (2010), p.133–134

- ^Călinescu, p.593

- ^abc"Diverse. Din Capitală. Drama din strada Lucacĭ", inEpoca,June 18, 1898, p.2

- ^"Ultime informațiuni", inEpoca,December 24, 1896, p.3

- ^abcNastasă (2010), p.51

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxxv; Nastasă (2010), p.134

- ^Nastasă (2010), p.50–51

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxxvi

- ^abcdeMaria Șveț, "Ovid-Aron Densușianu", inCalendar Național 2004: Anul Ștefan cel Mare și Sfânt,National Library of Moldova,Chișinău, 2004, p.110.ISBN9975-9992-9-8

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxi, xxxvi; Mitchievici, p.130–133; Onofreiet al.,p.243

- ^Mitchievici, p.131–133, 135

- ^Mitchievici, p.132

- ^abCalangiuet al.,p.xxi; Onofreiet al.,p.243

- ^P. N., "Recenzii. Elena Bacaloglu,În luptă",inViața Românească,Nr. 4/1906, p.175–176

- ^"Secțiunea literară. Premiul Năsturel", inAnalele Academiei Române. Seria II,Vol. XXIX, 1906–1907, p.251, 266–267

- ^Elena Bacaloglu, "Vis și realitate", inNoua Revistă Română,Nr. 9/1908, p.129–137

- ^"Revista Revistelor", inNoua Revistă Română,Nr. 6/1909, p.306

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxxv; Nastasă (2010), p.57, 117, 275

- ^abSallusto, p.174

- ^Payne, p.135

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxi; Călinescu, p.983; Onofreiet al.,p.242–243

- ^abcdeBurcea (2005), p.101

- ^abc"Transeuntes literarios", inLa Gaceta Literaria,Nr. 46/1928, p.4

- ^Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș,Memorii. II: 1910–1918,Grai și Suflet – Cultura Națională, Bucharest, 1999, p.9.ISBN973-95405-1-1

- ^"Memento", inNoua Revistă Română,Nr. 23/1912, p.356; Onofreiet al.,p.243

- ^Sallusto, p.174–175

- ^Tomi, p.280–282

- ^abcde(in Italian)"2a tornata di venerdì 16 giugno 1922. Interrogazioni e interpellanza",inAtti Parlamentari. Legislatura XXVI: CXXVII,p.6329

- ^Tomi, p.281–282

- ^Babeș, p.12

- ^Onofreiet al.,p.242

- ^Babeș, p.12–13

- ^Ileana-Stanca Desa, Elena Ioana Mălușanu, Cornelia Luminița Radu, Iliana Sulică,Publicațiile periodice românești (ziare, gazete, reviste). Vol. V, 1: Catalog alfabetic 1931–1935,Editura Academiei,Bucharest, 2009, p.261.ISBN973-27-0980-4

- ^"O mare prietenă...", p.95

- ^Bucur, p.77; Heinen, p.103

- ^abcHeinen, p.103

- ^"O mare prietenă...", p.95–96

- ^(in Italian)"2a tornata di lunedì 2 agosto 1920. Interrogazioni e interpellanza",inAtti Parlamentari. Legislatura XXV: LXXIX,p.4672

- ^Epure, p.116; Heinen, p.103

- ^"O mare prietenă...", p.96

- ^Epure, p.116

- ^Clark, p.38; Heinen, p.102–104

- ^Attila Gidó,Două decenii. Evreii din Cluj în perioada interbelică,Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităților Naționale, Cluj-Napoca, 2014, p.139.ISBN978-606-8377-28-5

- ^abcdFrancisco Veiga,La mística del ultranacionalismo: Historia de la Guardia de Hierro, Rumania, 1919–1941,Autonomous University of Barcelona,Bellaterra, 1989, p.140.ISBN84-7488-497-7

- ^Nastasă (2011), p.218, 234, 238, 240, 243, 268, 301, 304–305

- ^Constantini, p.20

- ^Constantini, p.19

- ^Clark, p. 38; Heinen, p.103–104

- ^Bucur, p.77; Constantini, p.19–20; Epure, p.115–116; Heinen, p.102–104

- ^Marin Petcu (ed.),Istoria jurnalismului din România în date. Enciclopedie cronologică,Polirom,Iași, 2012, p.1941.ISBN978-973-46-3855-0

- ^Bucur, p.77; Constantini, p.20; Heinen, p.103

- ^Constantini, p.20; Heinen, p.103

- ^Nastasă (2011), p.40

- ^Bucur,passim

- ^Heinen, p.102–103

- ^ab(in Romanian)Petre Țurlea, "Din nou despre poziția Partidului Naționalist Democrat față de evrei", in Vasile Ciobanu, Sorin Radu (eds.),Partide politice și minorități naționale din România în secolul XXArchived2012-04-25 at theWayback Machine,Vol. IV, TechnoMedia, Sibiu, 2009, p.139.ISBN978-606-8030-53-1

- ^Vestul României,Nr. 32/1923, p.3

- ^Clark, p.56, 60, 203

- ^(in Romanian)"Martirul Rosenthal",inClujul,Nr. 31/1923 (digitized by theBabeș-Bolyai UniversityTranssylvanica Online Library)

- ^(in Romanian)"Fascismul în Bihor",inVestul României,Nr. 29/1923, p.2 (digitized by theBabeș-Bolyai UniversityTranssylvanica Online Library)

- ^Heinen, p.103–105

- ^Payne, p.135–136

- ^Constantini, p.20; Heinen, p.104

- ^Vestul României,Nr. 32/1923, p.4

- ^"Știri", inRenașterea. Organul Oficial al Eparhiei Ortodoxe a Vadului, Feleacului, Geoagiului și Clujului,Nr. 26/1924, p.7

- ^Constantini, p.20; Heinen, p.103; Payne, p.135

- ^ab(in Romanian)"Mișcarea fașcistilor români. Programul fașcistilor",inClujul,Nr. 6/1924 (digitized by theBabeș-Bolyai UniversityTranssylvanica Online Library)

- ^Burcea (2005), p.101, 106; Constantini, p.20; Heinen, p.103

- ^Nastasă (2011), p.324–325

- ^(in Romanian)A. C. Cuza,"Chemare către toți românii",inÎnfrățirea Românească,Nr. 11/1925, p.3–4, 10 (digitized by theBabeș-Bolyai UniversityTranssylvanica Online Library). See also Mezarescu, p.47–48

- ^"200 Anti-Semitic Leaders Are Candidates for Election in Roumania",Jewish Telegraphic Agencyrelease, May 12, 1926

- ^Moldovan, p.42

- ^Moldovan, p.24

- ^(in Spanish)"Cámara de Comercio rumanoespañola",inLa Vanguardia,January 9, 1929, p.8 (hosted byLa Hemeroteca de La Vanguardia desde 1881)

- ^abBurcea (2005), p.102

- ^Bazil Gruia,"Complotul fascist", inChemarea Tinerimei Române,Nr. 21/1929, p.4

- ^"Procesul fasciștilor", inDreptatea,September 15, 1929, p.2

- ^Burcea (2005), p.101, 106

- ^Moldovan, p.45–46

- ^abMoldovan, p.44

- ^Mezarescu, p.327

- ^"Incăerare între cuziști și membri ai grupării 'Svastica de foc'", inAdevărul,May 30, 1937, p.5

- ^Nastasă (2010), p.310

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxxvi; Călinescu, p.1032

- ^Veronica Turcuș, "Din raporturile intelectualității universitare clujene interbelice cu elita academică italiană: Emil Panaitescu în corespondență cu Giuseppe Lugli", in theRomanian Academy(George Bariț Institute of History)Historica Yearbook2011, p.10

- ^Perpessicius,"Note. O. Densușianu și fascismul", inRevista Fundațiilor Regale,Nr. 4/1945, p.932–933

- ^Nastasă (2010), p.429–430, 448–449, 463–464. See also Calangiuet al.,p.lxxvi

- ^"Partea II. Particulare", inMonitorul Oficial,April 24, 1945, p.2520

- ^(in Italian)Carmen Burcea,"L'immagine della Romania sulla stampa del Ventennio (II)"Archived2018-04-21 at theWayback Machine,inThe Romanian Review of Political Sciences and International Relations,No. 2/2010, p.31

- ^Calangiuet al.,p.xxxv

References

[edit]- (in Romanian)"Buletin politic etc.",inVestul României,Nr. 32/1923 (digitized by theBabeș-Bolyai UniversityTranssylvanica Online Library)

- "O mare prietenă a Italiei: Elena Bacaloglu", inCele Trei Crișuri,Nr. 7-8/1933, p. 95–96

- Victor Babeș,"Răspuns rostit de D-l Prof. Dr. Victor Babeș", inGeorge Bacaloglu,Ardealul ca isvor cultural: Discurs de recepțiune rostit la Ateneul Român la 1 iunie 1924. Publicațiile Secției de Propagandă Crișul Negru, No. 10,Cele Trei Crișuri, Oradea-Mare, 1924, p. 12–16

- Maria Bucur,"Romania", in Kevin Passmore (ed.),Women, Gender and Fascism in Europe, 1919–45,Manchester University Press,Manchester, 2003, p. 57–78.ISBN0-7190-6083-4

- (in Romanian)Carmen Burcea,"Propaganda româneascã în Italia în perioada interbelică",inRevista de Științe Politice și Relații Internaționale,No. 1/2005, p. 94–108

- Anca Calangiu, Mihai Vatan, Maria Negraru,Ovid Densusianu 1873–1938. Biobibliografie,Central University Library,Bucharest, 1991.OCLC895141035

- George Călinescu,Istoria literaturii române de la origini până în prezent,Editura Minerva,Bucharest, 1986

- Roland Clark,Sfîntă tinerețe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică,Polirom,Iași, 2015.ISBN978-973-46-5357-7

- Emanuela Costantini,Nae Ionescu, Mircea Eliade, Emil Cioran: antiliberalismo nazionalista alla periferia d'Europa,Morlacchi Editore, Perugia, 2005.ISBN88-89422-66-1

- (in Romanian)Nicoleta Epure,"Relațiile româno-italiene de la sfârșitul Primului Război Mondial la 'Marșul asupra Romei' (noiembrie 1918 – octombrie 1922). Geneza unor contradicții de lungă durată"[permanent dead link],in theDimitrie Cantemir Christian UniversityAnalele UCDC. Seria Istorie,Vol. I, Nr. 1, 2010, p. 112–117

- Armin Heinen,Legiunea 'Arhanghelul Mihail': o contribuție la problema fascismului internațional,Humanitas,Bucharest, 2006.ISBN973-50-1158-1

- Ion Mezarescu,Partidul Național-Creștin: 1935–1937,Editura Paideia,Bucharest, 2018.ISBN978-606-748-256-0

- Angelo Mitchievici,Decadență și decadentism în contextul modernității românești și europene,Editura Curtea Veche,Bucharest, 2011.ISBN978-606-588-133-4

- (in Romanian)Andrei Moldovan,"Din corespondența lui Liviu Rebreanu",inVatra,Nr. 11/2011, p. 20–68

- Lucian Nastasă,

- (in Romanian)Intimitatea amfiteatrelor. Ipostaze din viața privată a universitarilor "literari" (1864–1948)Archived2016-03-03 at theWayback Machine,Editura Limes,Cluj-Napoca, 2010.ISBN978-973-726-469-5;e-bookversion at theRomanian AcademyGeorge Bariț Institute of History

- (in Romanian)Antisemitismul universitar în România (1919–1939). Mărturii documentare,Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităților Naționale &Editura Kriterion,Cluj-Napoca, 2011.ISBN978-606-92744-5-3

- Neonila Onofrei, Lucreția Angheluță, Liana Miclescu, Cornelia Gilorteanu, Tamara Teodorescu,Bibliografia românească modernă (1831–1918). Vol. I: A-C,Editura științifică și enciclopedică,Bucharest, 1984

- Stanley G. Payne,A History of Fascism, 1914–1945,University of Wisconsin Press,Madison, 1995.ISBN978-0-299-14874-4

- Filippo Sallusto,Itinerari epistolari del primo Novecento: lettere e testi inediti dell'archivio di Alberto Cappelletti,Luigi Pellegrini Editore, Cosenza, 2006.ISBN88-8101-321-5

- (in Romanian)Raluca Tomi,"Italieni în slujba Marii Uniri. Mărturii inedite"[permanent dead link],inRevista Istorică,Nr. 3–4/2010, p. 279–292 (republished byThe Research Group for the History of Minorities[permanent dead link])

- 1878 births

- 1940s deaths

- 20th-century essayists

- Romanian essayists

- Romanian literary critics

- Romanian women literary critics

- Romanian novelists

- Romanian opinion journalists

- Romanian women journalists

- Romanian newspaper editors

- Romanian newspaper founders

- Women newspaper editors

- Romanian propagandists

- Romanian women novelists

- 20th-century Romanian women writers

- Romanian women essayists

- Romanian writers in French

- Romanian translators

- 20th-century translators

- Romanian–French translators

- Italian–Romanian translators

- Impressionism

- Romanian women in business

- 20th-century Romanian women politicians

- Romanian fascists

- Women fascists

- Terrorism in Romania

- Leaders of political parties in Romania

- Writers from Bucharest

- Romanian people of Bulgarian descent

- University of Bucharest alumni

- Collège de France alumni

- Romanian expatriates in Italy

- Romanian people of World War I

- People deported from Italy

- Burials at Bellu Cemetery