Elf

Anelf(pl.:elves) is a type ofhumanoidsupernaturalbeing inGermanicfolklore.Elves appear especially inNorth Germanic mythology,being mentioned in theIcelandicPoetic EddaandSnorri Sturluson'sProse Edda.

In medievalGermanic-speaking cultures, elves generally seem to have been thought of as beings with magical powers and supernatural beauty, ambivalent towards everyday people and capable of either helping or hindering them.[1]However, the details of these beliefs have varied considerably over time and space and have flourished in both pre-Christian andChristian cultures.

Sometimes elves are, likedwarves,associated with craftsmanship.Wayland the Smithembodies this feature. He is known under many names, depending on the language in which the stories were distributed. The names includeVölundin Old Norse,Wēlandin Anglo-Saxon andWielandin German. The story of Wayland is also to be found in theProse Edda.[2]

The wordelfis found throughout theGermanic languagesand seems originally to have meant 'white being'. However, reconstructing the early concept of an elf depends largely on texts written by Christians, inOldandMiddle English,medieval German, andOld Norse.These associate elves variously with the gods ofNorse mythology,with causing illness, with magic, and with beauty and seduction.

After the medieval period, the wordelftended to become less common throughout the Germanic languages, losing out to alternative native terms likeZwerg('dwarf') in German andhuldra('hidden being') inNorth Germanic languages,and to loan-words likefairy(borrowed from French into most of the Germanic languages). Still, belief in elves persisted in theearly modern period,particularly in Scotland and Scandinavia, where elves were thought of as magically powerful people living, usually invisibly, alongside everyday human communities. They continued to be associated with causing illnesses and with sexual threats. For example, several early modern ballads in theBritish Islesand Scandinavia, originating in the medieval period, describe elves attempting to seduce or abduct human characters.

With urbanisation and industrialisation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, belief in elves declined rapidly (though Iceland has some claim to continued popular belief in elves). However, elves started to be prominent in the literature and art of educated elites from the early modern period onwards. These literary elves were imagined as tiny, playful beings, withWilliam Shakespeare'sA Midsummer Night's Dreambeing a key development of this idea. In the eighteenth century, GermanRomanticwriters were influenced by this notion of the elf and re-imported the English wordelfinto the German language.

From the Romantic idea of elves came the elves of popular culture that emerged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The "Christmas elves"of contemporary popular culture are a relatively recent creation, popularized during the late 19th century in the United States. Elves entered the twentieth-centuryhigh fantasygenre in the wake of works published by authors such asJ. R. R. Tolkien;these re-popularised the idea of elves as human-sized and humanlike beings. Elvesremain a prominent featureof fantasy media today.

Relationship with reality

Reality and perception

Elves have in many times and places been believed to be real beings.[3]Where enough people have believed in the reality of elves that those beliefs then had real effects in the world, they can be understood as part of people'sworldview,and as asocial reality:a thing which, like the exchange value of a dollar bill or the sense of pride stirred up by a national flag, is real because of people's beliefs rather than as an objective reality.[3]Accordingly, beliefs about elves and their social functions have varied over time and space.[4]

Even in the twenty-first century, fantasy stories about elves have been argued both to reflect and to shape their audiences' understanding of the real world,[5][6]and traditions about Santa Claus and his elves relate toChristmas.

Over time, people have attempted todemythologiseorrationalisebeliefs in elves in various ways.[7]

Integration into Christian cosmologies

Beliefs about elves have their origins before theconversion to Christianityand associatedChristianizationof northwest Europe. For this reason, belief in elves has, from the Middle Ages through into recent scholarship, often been labelled "pagan"and a"superstition."However, almost all surviving textual sources about elves were produced by Christians (whether Anglo-Saxon monks, medieval Icelandic poets, early modern ballad-singers, nineteenth-century folklore collectors, or even twentieth-century fantasy authors). Attested beliefs about elves, therefore, need to be understood as part ofGermanic-speakers' Christian cultureand not merely a relic of theirpre-Christian religion.Accordingly, investigating the relationship between beliefs in elves andChristian cosmologyhas been a preoccupation of scholarship about elves both in early times and modern research.[8]

Historically, people have taken three main approaches to integrate elves into Christian cosmology, all of which are found widely across time and space:

- Identifying elves with thedemonsof Judaeo-Christian-Mediterranean tradition.[9]For example:

- In English-language material: in theRoyal Prayer Bookfrom c. 900,elfappears as aglossfor "Satan".[10]In the late-fourteenth-centuryWife of Bath's Tale,Geoffrey Chaucerequates male elves withincubi(demons which rape sleeping women).[11]In theearly modern Scottish witchcraft trials,witnesses' descriptions of encounters with elves were often interpreted by prosecutors as encounters with theDevil.[12]

- In medieval Iceland,Snorri Sturlusonwrote in hisProse Eddaofljósálfaranddökkálfar('light-elves and dark-elves'), theljósálfarliving in the heavens and thedökkálfarunder the earth. The consensus of modern scholarship is that Snorri's elves are based on angels and demons of Christian cosmology.[13]

- Elves appear as demonic forces widely in medieval and early modern English, German, and Scandinavian prayers.[14][15][16]

- Viewing elves as being more or less like people and more or less outside Christian cosmology.[17]The Icelanders who copied thePoetic Eddadid not explicitly try to integrate elves into Christian thought. Likewise, the early modern Scottish people who confessed to encountering elves seem not to have thought of themselves as having dealings with theDevil.Nineteenth-century Icelandic folklore aboutelvesmostly presents them as a human agricultural community parallel to the visible human community, which may or may not be Christian.[18][19]It is possible that stories were sometimes told from this perspective as a political act, to subvert the dominance of the Church.[20]

- Integrating elves into Christian cosmology without identifying them as demons.[21]The most striking examples are serious theological treatises: the IcelandicTíðfordrif(1644) byJón Guðmundsson lærðior, in Scotland,Robert Kirk'sSecret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns, and Fairies(1691). This approach also appears in the Old English poemBeowulf,which lists elves among the races springing fromCain's murder of Abel.[22]The late thirteenth-centurySouth English Legendaryand some Icelandic folktales explain elves as angels that sided neither withLucifernor with God and were banished by God to earth rather than hell. One famous Icelandic folktale explains elves as the lost children of Eve.[23]

Demythologising elves as indigenous peoples

Some nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars attempted to rationalise beliefs in elves as folk memories of lost indigenous peoples. Since belief in supernatural beings is ubiquitous in human cultures, scholars no longer believe such explanations are valid.[24][25]Research has shown, however, that stories about elves have often been used as a way for people to thinkmetaphoricallyabout real-life ethnic others.[26][27][5]

Demythologising elves as people with illness or disability

Scholars have at times also tried to explain beliefs in elves as being inspired by people suffering certain kinds of illnesses (such asWilliams syndrome).[28]Elves were certainly often seen as a cause of illness, and indeed the English wordoafseems to have originated as a form ofelf:the wordelfcame to mean 'changelingleft by an elf' and then, because changelings were noted for their failure to thrive, to its modern sense 'a fool, a stupid person; a large, clumsy man or boy'.[29]However, it again seems unlikely that the origin of beliefs in elves itself is to be explained by people's encounters with objectively real people affected by disease.[30]

Etymology

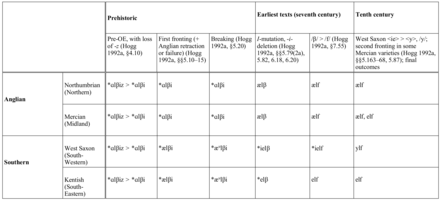

The English wordelfis from theOld Englishword most often attested asælf(whose plural would have been *ælfe). Although this word took a variety of forms in different Old English dialects, these converged on the formelfduring theMiddle Englishperiod.[33]During the Old English period, separate forms were used for female elves (such asælfen,putatively from Proto-Germanic*ɑlβ(i)innjō), but during the Middle English period the wordelfroutinely came to include female beings.[34]

The Old English forms arecognates– linguistic siblings stemming from a common origin – with medieval Germanic terms such as Old Norsealfr('elf'; pluralalfar), Old High Germanalp('evil spirit'; pl.alpî,elpî;feminineelbe), Burgundian *alfs('elf'), and Middle Low Germanalf('evil spirit').[35][36]These words must come fromProto-Germanic,the ancestor-language of the attestedGermanic languages;the Proto-Germanic forms are reconstructed as *ɑlβi-zand *ɑlβɑ-z.[35][37]

Germanic*ɑlβi-z~*ɑlβɑ-zis generally agreed to be a cognate with Latinalbus('(matt) white'), Old Irishailbhín('flock'), Ancient Greek ἀλφός (alphós;'whiteness, white leprosy';), and Albanianelb('barley'); and the Germanic word for 'swan' reconstructed as*albit-(compare Modern Icelandicálpt) is often thought to be derived from it. These all come from aProto-Indo-Europeanroot*h₂elbʰ-,and seem to be connected by the idea of whiteness. The Germanic word presumably originally meant 'white one', perhaps as a euphemism.[38]Jakob Grimmthought whiteness implied positive moral connotations, and, noting Snorri Sturluson'sljósálfar,suggested that elves were divinities of light.[38]This is not necessarily the case, however. For example, because the cognates suggest matt white rather than shining white, and because in medieval Scandinavian texts whiteness is associated with beauty,Alaric Hallhas suggested that elves may have been called 'the white people' because whiteness was associated with (specifically feminine) beauty.[38]Some scholars have argued that the namesAlbionandAlpsmay also be related (possibly through Celtic).[35][failed verification–see discussion]

A completely different etymology, makingelfa cognate with theṚbhus,semi-divine craftsmen in Indian mythology, was suggested byAdalbert Kuhnin 1855.[39]In this case, *ɑlβi-zwould connote the meaning 'skillful, inventive, clever', and could be a cognate with Latinlabor,in the sense of 'creative work'. While often mentioned, this etymology is not widely accepted.[40]

In proper names

Throughout the medieval Germanic languages,elfwas one of the nouns used inpersonal names,almost invariably as a first element. These names may have been influenced byCelticnames beginning inAlbio-such asAlbiorix.[41]

Personal names provide the only evidence forelfinGothic,which must have had the word *albs(plural *albeis). The most famous name of this kind isAlboin.Old English names inelf- include the cognate ofAlboinÆlfwine(literally "elf-friend", m.),Ælfric( "elf-powerful", m.),Ælfweard( "elf-guardian", m.), andÆlfwaru( "elf-care", f.). A widespread survivor of these in modern English isAlfred(Old EnglishÆlfrēd,"elf-advice" ). Also surviving are the English surnameElgar(Ælfgar,"elf-spear" ), and the name ofSt Alphege(Ælfhēah,"elf-tall" ).[42]German examples areAlberich,AlphartandAlphere(father ofWalter of Aquitaine)[43][44]and Icelandic examples includeÁlfhildur.These names suggest that elves were positively regarded in early Germanic culture. Of the many words for supernatural beings in Germanic languages, the only ones regularly used in personal names areelfand words denoting pagan gods, suggesting that elves were considered similar to gods.[45]

In later Old Icelandic,alfr( "elf" ) and the personal name which in Common Germanic had been *Aþa(l)wulfazboth coincidentally becameálfr~Álfr.[46]

Elves appear in some place names, though it is difficult to be sure how many of other words, including personal names, can appear similar toelf,because of confounding elements such as al- (fromeald) meaning "old". The clearest appearances of elves in English examples areElveden( "elves' hill", Suffolk) andElvendon( "elves' valley", Oxfordshire);[47]other examples may beEldon Hill( "Elves' hill", Derbyshire); andAlden Valley( "elves' valley", Lancashire). These seem to associate elves fairly consistently with woods and valleys.[48]

In medieval texts and post-medieval folk belief

Medieval English-language sources

As causes of illnesses

The earliest surviving manuscripts mentioning elves in any Germanic language are fromAnglo-Saxon England.Medieval English evidence has, therefore, attracted quite extensive research and debate.[49][50][51][52]In Old English, elves are most often mentioned in medical texts which attest to the belief that elves might afflict humans andlivestockwith illnesses: apparently mostly sharp, internal pains and mental disorders. The most famous of the medical texts is themetrical charmWið færstice( "against a stabbing pain" ), from the tenth-century compilationLacnunga,but most of the attestations are in the tenth-centuryBald's LeechbookandLeechbook III.This tradition continues into later English-language traditions too: elves continue to appear in Middle English medical texts.[53]

Belief in elves causing illnesses remained prominent in early modern Scotland, where elves were viewed as supernaturally powerful people who lived invisibly alongside everyday rural people.[54]Thus, elves were often mentioned in the early modern Scottish witchcraft trials: many witnesses in the trials believed themselves to have been given healing powers or to know of people or animals made sick by elves.[55][56]Throughout these sources, elves are sometimes associated with thesuccubus-like supernatural being called themare.[57]

While they may have been thought to cause diseases with magical weapons, elves are more clearly associated in Old English with a kind of magic denoted by Old Englishsīdenandsīdsa,a cognate with the Old Norseseiðr,and also paralleled in the Old IrishSerglige Con Culainn.[58][59]By the fourteenth century, they were also associated with the arcane practice ofalchemy.[53]

"Elf-shot"

In one or two Old English medical texts, elves might be envisaged as inflicting illnesses with projectiles. In the twentieth century, scholars often labelled the illnesses elves caused as "elf-shot",but work from the 1990s onwards showed that the medieval evidence for elves' being thought to cause illnesses in this way is slender;[60]debate about its significance is ongoing.[61]

The nounelf-shotis first attested in aScotspoem, "Rowlis Cursing," from around 1500, where "elf schot" is listed among a range of curses to be inflicted on some chicken thieves.[62]The term may not always have denoted an actual projectile:shotcould mean "a sharp pain" as well as "projectile." But in early modern Scotland,elf-schotand other terms likeelf-arrowheadare sometimes used ofneolithic arrow-heads,apparently thought to have been made by elves. In a few witchcraft trials, people attest that these arrow-heads were used in healing rituals and occasionally alleged that witches (and perhaps elves) used them to injure people and cattle.[63]Compare with the following excerpt from a 1749–50 ode byWilliam Collins:[64]

There every herd, by sad experience, knows

How, winged with fate, their elf-shot arrows fly,

When the sick ewe her summer food forgoes,

Or, stretched on earth, the heart-smit heifers lie.[64]

Size, appearance, and sexuality

Because of elves' association with illness, in the twentieth century, most scholars imagined that elves in the Anglo-Saxon tradition were small, invisible, demonic beings, causing illnesses with arrows. This was encouraged by the idea that "elf-shot" is depicted in theEadwine Psalter,in an image which became well known in this connection.[65]However, this is now thought to be a misunderstanding: the image proves to be a conventional illustration of God's arrows and Christian demons.[66]Rather, twenty-first century scholarship suggests that Anglo-Saxon elves, like elves in Scandinavia or the IrishAos Sí,were regarded as people.[67]

Like words for gods and men, the wordelfis used in personal names where words for monsters and demons are not.[68]Just asálfaris associated withÆsirin Old Norse, the Old EnglishWið færsticeassociates elves withēse;whatever this word meant by the tenth century, etymologically it denoted pagan gods.[69]In Old English, the pluralylfe(attested inBeowulf) is grammatically anethnonym(a word for an ethnic group), suggesting that elves were seen as people.[70][71]As well as appearing in medical texts, the Old English wordælfand its feminine derivativeælbinnewere used inglossesto translate Latin words fornymphs.This fits well with the wordælfscȳne,which meant "elf-beautiful" and is attested describing the seductively beautiful Biblical heroinesSarahandJudith.[72]

Likewise, in Middle English and early modern Scottish evidence, while still appearing as causes of harm and danger, elves appear clearly as humanlike beings.[73]They became associated with medieval chivalric romance traditions offairiesand particularly with the idea of aFairy Queen.A propensity to seduce or rape people becomes increasingly prominent in the source material.[74]Around the fifteenth century, evidence starts to appear for the belief that elves might steal human babies and replace them withchangelings.[75]

Decline in the use of the wordelf

By the end of the medieval period,elfwas increasingly being supplanted by the French loan-wordfairy.[76]An example isGeoffrey Chaucer's satirical taleSir Thopas,where the title character sets out in a quest for the "elf-queen", who dwells in the "countree of the Faerie".[77]

Old Norse texts

Mythological texts

Evidence for elf beliefs in medieval Scandinavia outside Iceland is sparse, but the Icelandic evidence is uniquely rich. For a long time, views about elves in Old Norse mythology were defined by Snorri Sturluson'sProse Edda,which talks aboutsvartálfar,dökkálfarandljósálfar( "black elves", "dark elves", and "light elves" ). For example, Snorri recounts how thesvartálfarcreate new blond hair for Thor's wifeSifafterLokihad shorn off Sif's long hair.[2]However, these terms are attested only in the Prose Edda and texts based on it. It is now agreed that they reflect traditions ofdwarves,demons,andangels,partly showing Snorri's "paganisation" of a Christian cosmology learned from theElucidarius,a popular digest of Christian thought.[13]

Scholars of Old Norse mythology now focus on references to elves in Old Norse poetry, particularly theElder Edda.The only character explicitly identified as an elf in classical Eddaic poetry, if any, isVölundr,the protagonist ofVölundarkviða.[79]However, elves are frequently mentioned in thealliteratingphraseÆsir ok Álfar('Æsir and elves') and its variants. This was a well-established poeticformula,indicating a strong tradition of associating elves with the group of gods known as theÆsir,or even suggesting that the elves and Æsir were one and the same.[80][81]The pairing is paralleled in the Old English poemWið færstice[69]and in the Germanic personal name system;[68]moreover, inSkaldic versethe wordelfis used in the same way as words for gods.[82]Sigvatr Þórðarson's skaldic travelogueAustrfaravísur,composed around 1020, mentions análfablót('elves' sacrifice') in Edskogen in what is now southern Sweden.[83]There does not seem to have been any clear-cut distinction between humans and gods; like the Æsir, then, elves were presumably thought of as being humanlike and existing in opposition to thegiants.[84]Many commentators have also (or instead) argued for conceptual overlap between elves anddwarvesin Old Norse mythology, which may fit with trends in the medieval German evidence.[85]

There are hints that the godFreyrwas associated with elves. In particular,Álfheimr(literally "elf-world" ) is mentioned as being given toFreyrinGrímnismál.Snorri Sturluson identified Freyr as one of theVanir.However, the termVaniris rare in Eddaic verse, very rare in Skaldic verse, and is not generally thought to appear in other Germanic languages. Given the link between Freyr and the elves, it has therefore long been suspected thatálfarandVanirare, more or less, different words for the same group of beings.[86][87][88]However, this is not uniformly accepted.[89]

Akenning(poetic metaphor) for the sun,álfröðull(literally "elf disc" ), is of uncertain meaning but is to some suggestive of a close link between elves and the sun.[90][91]

Although the relevant words are of slightly uncertain meaning, it seems fairly clear that Völundr is described as one of the elves inVölundarkviða.[92]As his most prominent deed in the poem is to rapeBöðvildr,the poem associates elves with being a sexual threat to maidens. The same idea is present in two post-classical Eddaic poems, which are also influenced bychivalric romanceorBretonlais,KötludraumurandGullkársljóð.The idea also occurs in later traditions in Scandinavia and beyond, so it may be an early attestation of a prominent tradition.[93]Elves also appear in a couple of verse spells, including theBergen rune-charmfrom among theBryggen inscriptions.[94]

Other sources

The appearance of elves in sagas is closely defined by genre. TheSagas of Icelanders,Bishops' sagas,and contemporarysagas,whose portrayal of the supernatural is generally restrained, rarely mentionálfar,and then only in passing.[95]But although limited, these texts provide some of the best evidence for the presence of elves in everyday beliefs in medieval Scandinavia. They include a fleeting mention of elves seen out riding in 1168 (inSturlunga saga); mention of análfablót( "elves' sacrifice" ) inKormáks saga;and the existence of the euphemismganga álfrek('go to drive away the elves') for "going to the toilet" inEyrbyggja saga.[95][96]

TheKings' sagasinclude a rather elliptical but widely studied account of an early Swedish king being worshipped after his death and being calledÓlafr Geirstaðaálfr('Ólafr the elf of Geirstaðir'), and a demonic elf at the beginning ofNorna-Gests þáttr.[97]

Thelegendary sagastend to focus on elves as legendary ancestors or on heroes' sexual relations with elf-women. Mention of the land ofÁlfheimris found inHeimskringlawhileÞorsteins saga Víkingssonarrecounts a line of local kings who ruled overÁlfheim,who since they had elven blood were said to be more beautiful than most men.[98][99]According toHrólfs saga kraka,Hrolfr Kraki's half-sisterSkuldwas thehalf-elvenchild of King Helgi and an elf-woman (álfkona). Skuld was skilled in witchcraft (seiðr). Accounts of Skuld in earlier sources, however, do not include this material. TheÞiðreks sagaversion of theNibelungen(Niflungar) describesHögnias the son of a human queen and an elf, but no such lineage is reported in the Eddas,Völsunga saga,or theNibelungenlied.[100]The relatively few mentions of elves in thechivalric sagastend even to be whimsical.[101]

In hisRerum Danicarum fragmenta(1596) written mostly in Latin with some Old Danish and Old Icelandic passages,Arngrímur Jónssonexplains the Scandinavian and Icelandic belief in elves (calledAllffuafolch).[102] Both Continental Scandinavia and Iceland have a scattering of mentions of elves in medical texts, sometimes in Latin and sometimes in the form of amulets, where elves are viewed as a possible cause of illness. Most of them have Low German connections.[103][104][105]

Medieval and early modern German texts

TheOld High Germanwordalpis attested only in a small number of glosses. It is defined by theAlthochdeutsches Wörterbuchas a "nature-god or nature-demon, equated with theFaunsof Classical mythology... regarded as eerie, ferocious beings... As themarehe messes around with women ".[106]Accordingly, the German wordAlpdruck(literally "elf-oppression" ) means "nightmare". There is also evidence associating elves with illness, specifically epilepsy.[107]

In a similar vein, elves are in Middle High German most often associated with deceiving or bewildering people in a phrase that occurs so often it would appear to be proverbial:die elben/der alp trieget mich( "the elves/elf are/is deceiving me" ).[108]The same pattern holds in Early Modern German.[109][110]This deception sometimes shows the seductive side apparent in English and Scandinavian material:[107]most famously, the early thirteenth-centuryHeinrich von Morungen's fifthMinnesangbegins "Von den elben wirt entsehen vil manic man / Sô bin ich von grôzer liebe entsên" ( "full many a man is bewitched by elves / thus I too am bewitched by great love" ).[111]Elbewas also used in this period to translate words for nymphs.[112]

In later medieval prayers, Elves appear as a threatening, even demonic, force. For example, some prayers invoke God's help against nocturnal attacks byAlpe.[113]Correspondingly, in the early modern period, elves are described in north Germany doing the evil bidding of witches;Martin Lutherbelieved his mother to have been afflicted in this way.[114]

As in Old Norse, however, there are few characters identified as elves. It seems likely that in the German-speaking world, elves were to a significant extent conflated with dwarves (Middle High German:getwerc).[115]Thus, some dwarves that appear in German heroic poetry have been seen as relating to elves. In particular, nineteenth-century scholars tended to think that the dwarf Alberich, whose name etymologically means "elf-powerful," was influenced by early traditions of elves.[116][117]

Post-medieval folklore

Britain

From around theLate Middle Ages,the wordelfbegan to be used in English as a term loosely synonymous with the French loan-wordfairy;[119]in elite art and literature, at least, it also became associated with diminutive supernatural beings likePuck,hobgoblins,Robin Goodfellow, the English and Scotsbrownie,and the Northumbrian Englishhob.[120]

However, in Scotland and parts of northern England near the Scottish border, beliefs in elves remained prominent into the nineteenth century.James VI of Scotlandand Robert Kirk discussed elves seriously; elf beliefs are prominently attested in the Scottish witchcraft trials, particularly the trial ofIssobel Gowdie;and related stories also appear in folktales,[121]There is a significant corpus of ballads narrating stories about elves, such asThomas the Rhymer,where a man meets a female elf;Tam Lin,The Elfin Knight,andLady Isabel and the Elf-Knight,in which an Elf-Knight rapes, seduces, or abducts a woman; andThe Queen of Elfland's Nourice,a woman is abducted to be a wet-nurse to the elf queen's baby, but promised that she might return home once the child is weaned.[122]

Terminology

InScandinavian folklore,many humanlike supernatural beings are attested, which might be thought of as elves and partly originate in medieval Scandinavian beliefs. However, the characteristics and names of these beings have varied widely across time and space, and they cannot be neatly categorised. These beings are sometimes known by words descended directly from the Old Norseálfr.However, in modern languages, traditional terms related toálfrhave tended to be replaced with other terms. Things are further complicated because when referring to the elves of Old Norse mythology, scholars have adopted new forms based directly on the Old Norse wordálfr.The following table summarises the situation in the main modern standard languages of Scandinavia.[123]

| language | terms related toelfin traditional usage | main terms of similar meaning in traditional usage | scholarly term for Norse mythological elves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danish | elver,elverfolk,ellefolk | nøkke,nisse,fe | alf |

| Swedish | älva | skogsrå, skogsfru,tomte | alv,alf |

| Norwegian (bokmål) | alv,alvefolk | vette,huldra | alv |

| Icelandic | álfur | huldufólk | álfur |

Appearance and behaviour

The elves of Norse mythology have survived into folklore mainly as females, living in hills and mounds of stones.[124]The Swedishälvorwere stunningly beautiful girls who lived in the forest with an elven king.[125][126]

The elves could be seen dancing over meadows, particularly at night and on misty mornings. They left a circle where they had danced, calledälvdanser(elf dances) orälvringar(elf circles), and to urinate in one was thought to cause venereal diseases. Typically, elf circles werefairy ringsconsisting of a ring of small mushrooms, but there was also another kind of elf circle. In the words of the local historian Anne Marie Hellström:[124]

... on lake shores, where the forest met the lake, you could find elf circles. They were round places where the grass had been flattened like a floor. Elves had danced there. ByLake Tisnaren,I have seen one of those. It could be dangerous, and one could become ill if one had trodden over such a place or if one destroyed anything there.[124]

If a human watched the dance of the elves, he would discover that even though only a few hours seemed to have passed, many years had passed in the real world. Humans being invited or lured to the elf dance is a common motif transferred from older Scandinavian ballads.[127]

Elves were not exclusively young and beautiful. In the Swedish folktaleLittle Rosa and Long Leda,an elvish woman (älvakvinna) arrives in the end and saves the heroine, Little Rose, on the condition that the king's cattle no longer graze on her hill. She is described as a beautiful old woman and by her aspect people saw that she belonged to thesubterraneans.[128]

In ballads

Elves have a prominent place in several closely related ballads, which must have originated in the Middle Ages but are first attested in the early modern period.[122]Many of these ballads are first attested inKaren Brahes Folio,a Danish manuscript from the 1570s, but they circulated widely in Scandinavia and northern Britain. They sometimes mention elves because they were learned by heart, even though that term had become archaic in everyday usage. They have therefore played a major role in transmitting traditional ideas about elves in post-medieval cultures. Indeed, some of the early modern ballads are still quite widely known, whether through school syllabuses or contemporary folk music. They, therefore, give people an unusual degree of access to ideas of elves from older traditional culture.[129]

The ballads are characterised by sexual encounters between everyday people and humanlike beings referred to in at least some variants as elves (the same characters also appear asmermen,dwarves, and other kinds of supernatural beings). The elves pose a threat to the everyday community by lure people into the elves' world. The most famous example isElveskudand its many variants (paralleled in English asClerk Colvill), where a woman from the elf world tries to tempt a young knight to join her in dancing, or to live among the elves; in some versions he refuses, and in some he accepts, but in either case he dies, tragically. As inElveskud,sometimes the everyday person is a man and the elf a woman, as also inElvehøj(much the same story asElveskud,but with a happy ending),Herr Magnus og Bjærgtrolden,Herr Tønne af Alsø,Herr Bøsmer i elvehjem,or the Northern BritishThomas the Rhymer.Sometimes the everyday person is a woman, and the elf is a man, as in the northern BritishTam Lin,The Elfin Knight,andLady Isabel and the Elf-Knight,in which the Elf-Knight bears away Isabel to murder her, or the ScandinavianHarpans kraft.InThe Queen of Elfland's Nourice,a woman is abducted to be awet nurseto the elf-queen's baby, but promised that she might return home once the child is weaned.[122]

As causes of illness

In folk stories, Scandinavian elves often play the role of disease spirits. The most common, though the also most harmless case was various irritating skinrashes,which were calledälvablåst(elven puff) and could be cured by a forceful counter-blow (a handy pair ofbellowswas most useful for this purpose).Skålgropar,a particular kind ofpetroglyph(pictogram on a rock) found in Scandinavia, were known in older times asälvkvarnar(elven mills), because it was believed elves had used them. One could appease the elves by offering a treat (preferably butter) placed into an elven mill.[123]

In order to protect themselves and their livestock against malevolent elves, Scandinavians could use a so-called Elf cross (Alfkors,ÄlvkorsorEllakors), which was carved into buildings or other objects.[130]It existed in two shapes, one was apentagram,and it was still frequently used in early 20th-century Sweden as painted or carved onto doors, walls, and household utensils to protect against elves.[130]The second form was an ordinary cross carved onto a round or oblong silver plate.[130]This second kind of elf cross was worn as a pendant in a necklace, and to have sufficient magic, it had to be forged during three evenings with silver, from nine different sources of inherited silver.[130]In some locations it also had to be on the altar of a church for three consecutive Sundays.[130]

Modern continuations

In Iceland, expressing belief in thehuldufólk( "hidden people" ), elves that dwell in rock formations, is still relatively common. Even when Icelanders do not explicitly express their belief, they are often reluctant to express disbelief.[131]A 2006 and 2007 study by the University of Iceland's Faculty of Social Sciences revealed that many would not rule out the existence of elves and ghosts, a result similar to a 1974 survey byErlendur Haraldsson.The lead researcher of the 2006–2007 study,Terry Gunnell,stated: "Icelanders seem much more open to phenomena like dreaming the future, forebodings, ghosts and elves than other nations".[132]Whether significant numbers of Icelandic people do believe in elves or not, elves are certainly prominent in national discourses. They occur most often in oral narratives and news reporting in which they disrupt house- and road-building. In the analysis ofValdimar Tr. Hafstein,"narratives about the insurrections of elves demonstrate supernatural sanction against development and urbanization; that is to say, the supernaturals protect and enforce religious values and traditional rural culture. The elves fend off, with more or less success, the attacks, and advances of modern technology, palpable in the bulldozer."[133]Elves are also prominent, in similar roles, in contemporary Icelandic literature.[134]

Folk stories told in the nineteenth century about elves are still told in modern Denmark and Sweden. Still, they now feature ethnic minorities in place of elves in essentially racist discourse. In an ethnically fairly homogeneous medieval countryside, supernatural beings provided theOtherthrough which everyday people created their identities; in cosmopolitan industrial contexts, ethnic minorities or immigrants are used in storytelling to similar effect.[27]

Post-medieval elite culture

Early modern elite culture

Early modern Europe saw the emergence for the first time of a distinctiveelite culture:while theReformationencouraged new skepticism and opposition to traditional beliefs, subsequent Romanticism encouraged thefetishisationof such beliefs by intellectual elites. The effects of this on writing about elves are most apparent in England and Germany, with developments in each country influencing the other. In Scandinavia, the Romantic movement was also prominent, and literary writing was the main context for continued use of the wordelf,except in fossilised words for illnesses. However, oral traditions about beings like elves remained prominent in Scandinavia into the early twentieth century.[127]

Elves entered early modern elite culture most clearly in the literature of Elizabethan England.[120]HereEdmund Spenser'sFaerie Queene(1590–) usedfairyandelfinterchangeably of human-sized beings, but they are complex, imaginary and allegorical figures. Spenser also presented his own explanation of the origins of theElfeandElfin kynd,claiming that they were created byPrometheus.[135]Likewise,William Shakespeare,in a speech inRomeo and Juliet(1592) has an "elf-lock" (tangled hair) being caused byQueen Mab,who is referred to as "thefairies'midwife".[136]Meanwhile,A Midsummer Night's Dreampromoted the idea that elves were diminutive and ethereal. The influence of Shakespeare andMichael Draytonmade the use ofelfandfairyfor very small beings the norm, and had a lasting effect seen in fairy tales about elves, collected in the modern period.[137]

The Romantic movement

Early modern English notions of elves became influential in eighteenth-century Germany. TheModern GermanElf(m) andElfe(f) was introduced as a loan-word from English in the 1740s[138][139]and was prominent inChristoph Martin Wieland's 1764 translation ofA Midsummer Night's Dream.[140]

AsGerman Romanticismgot underway and writers started to seek authentic folklore, Jacob Grimm rejectedElfas a recent Anglicism, and promoted the reuse of the old formElb(pluralElbeorElben).[139][141]In the same vein,Johann Gottfried Herdertranslated the Danish balladElveskudin his 1778 collection of folk songs,Stimmen der Völker in Liedern,as "Erlkönigs Tochter"(" The Erl-king's Daughter "; it appears that Herder introduced the termErlköniginto German through a mis-Germanisation of the Danish word forelf). This in turn inspired Goethe's poemDer Erlkönig.However, Goethe added another new meaning, as the German word "Erle" does not mean "elf", but "black alder" - the poem about theErlenkönigis set in the area of an alder quarry in the Saale valley in Thuringia. Goethe's poem then took on a life of its own, inspiring the Romantic concept of theErlking,which was influential on literary images of elves from the nineteenth century on.[142]

In Scandinavia too, in the nineteenth century, traditions of elves were adapted to include small, insect-winged fairies. These are often called "elves" (älvorin modern Swedish,alferin Danish,álfarin Icelandic), although the more formal translation in Danish isfeer.Thus, thealffound in the fairy taleThe Elf of the Roseby Danish authorHans Christian Andersenis so tiny he can have a rose blossom for home, and "wings that reached from his shoulders to his feet". Yet Andersen also wrote aboutelvereinThe Elfin Hill.The elves in this story are more alike those of traditional Danish folklore, who were beautiful females, living in hills and boulders, capable of dancing a man to death. Like thehuldrain Norway and Sweden, they are hollow when seen from the back.[143]

English and German literary traditions both influenced the BritishVictorianimage of elves, which appeared in illustrations as tiny men and women withpointed earsand stocking caps. An example isAndrew Lang's fairy talePrincess Nobody(1884), illustrated byRichard Doyle,where fairies are tiny people withbutterflywings. In contrast, elves are small people with red stocking caps. These conceptions remained prominent in twentieth-century children's literature, for exampleEnid Blyton'sThe Faraway Treeseries, and were influenced by German Romantic literature. Accordingly, in theBrothers Grimmfairy taleDie Wichtelmänner(literally, "the little men" ), the title protagonists are two tiny naked men who help a shoemaker in his work. Even thoughWichtelmännerare akin to beings such askobolds,dwarvesandbrownies,the tale was translated into English by Margaret Hunt in 1884 asThe Elves and the Shoemaker.This shows how the meanings ofelfhad changed and was in itself influential: the usage is echoed, for example, in the house-elf ofJ. K. Rowling'sHarry Potterstories. In his turn, J. R. R. Tolkien recommended using the older German formElbin translations of his works, as recorded in hisGuide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings(1967).Elb, Elbenwas consequently introduced in 1972German translation ofThe Lord of the Rings,repopularising the form in German.[144]

In popular culture

Christmas elf

With industrialisation and mass education, traditional folklore about elves waned; however, as the phenomenon of popular culture emerged, elves were re-imagined, in large part based on Romantic literary depictions and associatedmedievalism.[144]

As American Christmas traditions crystallized in the nineteenth century, the 1823 poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas"(widely known as" 'Twas the Night before Christmas ") characterized St Nicholas himself as" a right jolly old elf. "However, it was his little helpers, inspired partly by folktales likeThe Elves and the Shoemaker,who became known as "Santa's elves"; the processes through which this came about are not well-understood, but one key figure was a Christmas-related publication by the German-American cartoonistThomas Nast.[145][144]Thus in the US, Canada, UK, and Ireland, the modern children's folklore of Santa Claus typically includes small, nimble, green-clad elves with pointy ears, long noses, and pointy hats, as Santa's helpers. They make the toys in a workshop located in the North Pole.[146]The role of elves as Santa's helpers has continued to be popular, as evidenced by the success of the popular Christmas movieElf.[144]

Fantasy fiction

Thefantasygenre in the twentieth century grew out of nineteenth-century Romanticism, in which nineteenth-century scholars such asAndrew Langand the Grimm brothers collected fairy stories from folklore and in some cases retold them freely.[147]

A pioneering work of the fantasy genre wasThe King of Elfland's Daughter,a 1924 novel byLord Dunsany.TheElves of Middle-earthplayed a central role inTolkien's legendarium,notablyThe HobbitandThe Lord of the Rings;this legendarium was enormously influential on subsequent fantasy writing. Tolkien's writing had such influence that in the 1960s and afterwards, elves speaking an elvish language similar to those in Tolkien's novels became staple non-human characters inhigh fantasyworks and in fantasyrole-playing games.Post-Tolkien fantasy elves (which feature not only in novels but also in role-playing games such asDungeons & Dragons) are often portrayed as being wiser and more beautiful than humans, with sharper senses and perceptions as well. They are said to be gifted inmagic,mentally sharp and lovers of nature, art, and song. They are often skilled archers. A hallmark of many fantasy elves is their pointed ears.[147]

In works where elves are the main characters, such asThe Silmarillionor Wendy and Richard Pini's comic book seriesElfquest,elves exhibit a similar range of behaviour to a human cast, distinguished largely by their superhuman physical powers. However, where narratives are more human-centered, as inThe Lord of the Rings,elves tend to sustain their role as powerful, sometimes threatening, outsiders.[147]Despite the obvious fictionality of fantasy novels and games, scholars have found that elves in these works continue to have a subtle role in shaping the real-life identities of their audiences. For example, elves can function to encode real-world racial others invideo games,[5][148]or to influence gender norms through literature.[6]

Equivalents in non-Germanic traditions

Beliefs in humanlike supernatural beings are widespread in human cultures, and many such beings may be referred to aselvesin English.

Europe

Elfish beings appear to have been a common characteristic withinIndo-European mythologies.[150]In the Celtic-speaking regions of north-west Europe, the beings most similar to elves are generally referred to with theGaelictermAos Sí.[151][152]The equivalent term in modern Welsh isTylwyth Teg.In theRomance-speaking world,beings comparable to elves are widely known by words derived from Latinfata('fate'), which came into English asfairy.This word became partly synonymous withelfby the early modern period.[119]Other names also abound, however, such as the SicilianDonas de fuera('ladies from outside'),[153]or Frenchbonnes dames('good ladies').[154]In theFinnic-speaking world,the term usually thought most closely equivalent toelfishaltija(in Finnish) orhaldaja(Estonian).[155]Meanwhile, an example of an equivalent in theSlavic-speaking worldis thevila(pluralvile) of Serbo-Croatian (and, partly, Slovene)folklore.[156]Elves bear some resemblances to thesatyrsofGreek mythology,who were also regarded as woodland-dwelling mischief-makers.[157]

In the Italian region ofRomagna,themazapégulare mischievous nocturnal elves who disrupt sleep and torment beautiful young girls.[158][159][160][161]

Asia and Oceania

Some scholarship draws parallels between the Arabian tradition ofjinnwith the elves of medieval Germanic-language cultures.[162]Some of the comparisons are quite precise: for example, the root of the wordjinnwas used in medieval Arabic terms for madness and possession in similar ways to the Old English wordylfig,[163]which was derived fromelfand also denoted prophetic states of mind implicitly associated with elfish possession.[164]

Khmer culture in Cambodia includes theMrenh kongveal,elfish beings associated with guarding animals.[165]

In the animistic precolonial beliefs of thePhilippines,the world can be divided into the material world and the spirit world. All objects, animate or inanimate, have a spirit calledanito.Non-humananitoare known asdiwata,usually euphemistically referred to asdili ingon nato('those unlike us'). They inhabit natural features like mountains, forests, old trees, caves, reefs, etc., as well as personify abstract concepts and natural phenomena. They are similar to elves in that they can be helpful or hateful but are usually indifferent to mortals. They can be mischievous and cause unintentional harm to humans, but they can also deliberately cause illnesses and misfortunes when disrespected or angered. Spanish colonizers equated them with elves and fairy folklore.[166]

Orang bunianare supernatural beings inMalaysian, BruneianandIndonesian folklore,[167]invisible to most humans except those with spiritual sight. While the term is often translated as "elves", it literally translates to "hidden people" or "whistling people". Their appearance is nearly identical to humans dressed in an ancientSoutheast Asianstyle.

In Māori culture,Patupaiareheare beings similar to European elves and fairies.[168]

See also

Footnotes

Citations

- ^For discussion of a previous formulation of this sentence, seeJakobsson (2015).

- ^abManea, Irina-Maria (8 March 2022)."Elves & Dwarves in Norse Mythology".worldhistory.org.World History Encyclopedia.Retrieved19 December2022.

- ^abHall (2007),pp. 8–9.

- ^Jakobsson (2006);Jakobsson (2015);Shippey (2005);Hall (2007),pp. 16–17, 230–231;Gunnell (2007).

- ^abcPoor, Nathaniel (September 2012). "Digital Elves as a Racial Other in Video Games: Acknowledgment and Avoidance".Games and Culture.7(5): 375–396.doi:10.1177/1555412012454224.S2CID147432832.

- ^abBergman (2011),pp. 215–29.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 6–9.

- ^Jolly (1996);Shippey (2005);Green (2016).

- ^e.g.Jolly (1992),p. 172

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 71–72.

- ^Hall (2007),p. 162.

- ^Hall (2005),pp. 30–32.

- ^abShippey (2005),pp. 180–81;Hall (2007),pp. 23–26;Gunnell (2007),pp. 127–28;Tolley (2009),vol. I, p. 220.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 69–74, 106 n. 48 & 122 on English evidence

- ^Hall (2007),p. 98, fn. 10 andSchulz (2000),pp. 62–85 on German evidence.

- ^Þorgeirsson (2011),pp. 54–58 on Icelandic evidence.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 172–175.

- ^Shippey (2005),pp. 161–68.

- ^Alver, Bente Gullveig;Selberg, Torunn (1987),'Folk Medicine as Part of a Larger Concept Complex', Arv,43:21–44.

- ^Ingwersen (1995),pp. 83–89.

- ^Shippey (2005),p.[page needed].

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 69–74.

- ^Hall (2007),p. 75;Shippey (2005),pp. 174, 185–86.

- ^Spence (1946),pp. 53–64, 115–131.

- ^Purkiss (2000),pp. 5–7.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 47–53.

- ^abTangherlini, Timothy R. (1995). "From Trolls to Turks: Continuity and Change in Danish Legend Tradition".Scandinavian Studies.67(1): 32–62.JSTOR40919729.;cf.Ingwersen (1995),pp. 78–79, 81.

- ^Westfahl, Gary; Slusser, George Edgar (1999).Nursery Realms: Children in the Worlds of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror.University of Georgia Press. p. 153.ISBN9780820321448.

- ^"oaf, n.1.[permanent dead link]","auf(e, n.[permanent dead link]",OED Online, Oxford University Press,June 2018. Accessed 1 September 2018.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 7–8.

- ^Phonology.A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 1. Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell.1992.

- ^Hall (2007),p. 178 (fig. 7).

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 176–81.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 75–88, 157–66.

- ^abcOrel (2003),p. 13.

- ^Hall (2007),p. 5.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 5, 176–77.

- ^abcHall (2007),pp. 54–55.

- ^Kuhn (1855),p.110;Schrader (1890),p.163.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 54–55 fn. 1.

- ^Hall (2007),p. 56.

- ^Reaney, P. H.; Wilson, R. M. (1997).A Dictionary of English Surnames.Oxford University Press. pp.6, 9.ISBN978-0-19-860092-3.

- ^Paul, Hermann(1900).Grundriss der germanischen philologie unter mitwirkung.K. J. Trübner. p.268.

- ^Althof, Hermann, ed. (1902).Das Waltharilied.Dieterich. p. 114.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 58–61.

- ^De Vries, Jan(1962). "Álfr".Altnordisches etymologisches Wörterbuch(2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill.

- ^Ann Cole, 'Two Chiltern Place-names Reconsidered: Elvendon and Misbourne',Journal of the English Place-name Society,50 (2018), 65-74 (p. 67).

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 64–66.

- ^Jolly (1996).

- ^Shippey (2005).

- ^Hall (2007).

- ^Green (2016).

- ^abHall (2007),pp. 88–89, 141;Green (2003);Hall (2006).

- ^Henderson & Cowan (2001);Hall (2005).

- ^Purkiss (2000),pp. 85–115; Cf.Henderson & Cowan (2001);Hall (2005).

- ^Hall (2007),p. 112–15.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 124–26, 128–29, 136–37, 156.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 119–156.

- ^Tolley (2009),vol. I, p. 221.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 96–118.

- ^Tolley (2009),vol. I, p. 220.

- ^Hall (2005),p. 23.

- ^Hall (2005).

- ^abCarlyle (1788),i 68, stanza II. 1749 date of composition is given on p. 63.

- ^Grattan, J. H. G.;Singer, Charles(1952),Anglo-Saxon Magic and Medicine Illustrated Specially from the Semi-Pagan Text 'Lacnunga',Publications of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum, New Series, 3, London: Oxford University Press, frontispiece.

- ^Jolly (1998).

- ^Shippey (2005),pp. 168–76;Hall (2007),esp. pp. 172–75.

- ^abHall (2007),pp. 55–62.

- ^abHall (2007),pp. 35–63.

- ^Huld, Martin E (1998). "On the Heterclitic Declension of Germanic Divinities and the Status of theVanir".Studia Indogermanica Lodziensia.2:136–46.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 62–63;Tolley (2009),vol. I, p. 209

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 75–95.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 157–66;Shippey (2005),pp. 172–76.

- ^Shippey (2005),pp. 175–76;Hall (2007),pp. 130–48;Green (2016),pp. 76–109.

- ^Green (2016),pp. 110–46.

- ^Hall (2005),p. 20.

- ^Keightley (1850),p. 53.

- ^Hall (2009),p. 208, fig.1.

- ^Dumézil (1973),p. 3.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 34–39.

- ^Þorgeirsson (2011),pp. 49–50.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 28–32.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 30–31.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 31–34, 42, 47–53.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 32–33.

- ^Simek, Rudolf(December 2010)."The Vanir: An Obituary"(PDF).The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter:10–19.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 35–37.

- ^Frog, Etunimetön; Roper, Jonathan (May 2011)."Verses versus the Vanir: Response to Simek's" Vanir Obituary "(PDF).The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter:29–37.

- ^Tolley (2009),vol. I, pp. 210–217.

- ^Motz, Lotte (1973)."Of Elves and Dwarves"(PDF).Arv: Tidskrift för Nordisk Folkminnesforskning.29–30: 99.[permanent dead link]

- ^Hall (2004),p. 40.

- ^Jakobsson (2006);Hall (2007),pp. 39–47.

- ^Þorgeirsson (2011),pp. 50–52.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 133–34.

- ^abJakobsson (2006),p. 231.

- ^Tolley (2009),vol. I, pp. 217–218.

- ^Jakobsson (2006),pp. 231–232;Hall (2007),pp. 26–27;Tolley (2009),vol. I, pp. 218–219.

- ^The Saga of Thorstein, Viking's SonArchived14 April 2005 at theWayback Machine(Old Norse original:Þorsteins saga Víkingssonar). Chapter 1.

- ^Ashman Rowe, Elizabeth (2010), Arnold, Martin; Finlay, Alison (eds.),"Sǫgubrot af fornkonungum::Mythologised History for Late Thirteenth-century Iceland "(PDF),Making History: Essays on the Fornaldarsögur,Viking Society for Northern Research, pp. 11–12

- ^Jakobsson (2006),p. 232.

- ^Þorgeirsson (2011),pp. 52–54.

- ^Olrik, Axel(1894)."Skjoldungasaga in Arngrim Jonssons Udtog".Aarbøger for nordisk oldkyndighed og historie:130–131.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 132–33.

- ^Þorgeirsson (2011),pp. 54–58.

- ^Simek, Rudolf(2011)."Elves and Exorcism: Runic and Other Lead Amulets in Medieval Popular Religion".In Anlezark, Daniel (ed.).Myths, Legends, and Heroes: Essays on Old Norse and Old English Literature in Honour of John McKinnell.Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–52.ISBN978-0-8020-9947-1.Retrieved22 September2020.

- ^"Naturgott oder -dämon, den Faunen der antiken Mythologie gleichgesetzt... er gilt als gespenstisches, heimtückisches Wesen... als Nachtmahr spielt er den Frauen mit ";Karg-Gasterstädt & Frings (1968),s.v.alb.

- ^abEdwards (1994).

- ^Edwards (1994),pp. 16–17, at 17.

- ^Grimm (1883b),p. 463.

- ^In Lexer's Middle High German dictionary underalp, albis an example: Pf. arzb. 2 14b=Pfeiffer (1863),p. 44 (Pfeiffer, F. (1863). "Arzenîbuch 2= Bartholomäus" (Mitte 13. Jh.) ".Zwei deutsche Arzneibücher aus dem 12. und 13. Jh.Wien.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)): "Swen der alp triuget, rouchet er sich mit der verbena, ime enwirret als pald niht;" meaning: 'When analpdeceives you, fumigate yourself withverbenaand the confusion will soon be gone'. The editor glossesalphere as "malicious, teasing spirit" (German:boshafter neckende geist) - ^Edwards (1994),p. 13.

- ^Edwards (1994),p. 17.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 125–26.

- ^Edwards (1994),pp. 21–22.

- ^Motz (1983),esp. pp. 23–66.

- ^Weston, Jessie Laidlay(1903),The legends of the Wagner drama: studies in mythology and romance,C. Scribner's sons, p. 144

- ^Grimm (1883b),p. 453.

- ^Scott (1803),p. 266.

- ^abHall (2005),pp. 20–21.

- ^abBergman (2011),pp. 62–74.

- ^Henderson & Cowan (2001).

- ^abcTaylor (2014),pp. 199–251.

- ^abO[lrik], A[xel](1915–1930)."Elverfolk".In Blangstrup, Chr.; et al. (eds.).Salmonsens konversationsleksikon.Vol. VII (2nd ed.). pp. 133–136.

- ^abcHellström, Anne Marie (1990).En Krönika om Åsbro.Libris. p. 36.ISBN978-91-7194-726-0.

- ^For the Swedish belief inälvorsee mainlySchön, Ebbe (1986). "De fagra flickorna på ängen".Älvor, vättar och andra väsen.Rabben & Sjogren.ISBN978-91-29-57688-7.

- ^Keightley (1850),pp. 78–. Chapter: "Scandinavia: Elves"

- ^abTaylor (2014).

- ^"Lilla Rosa och Långa Leda".Svenska folksagor[Swedish Folktales] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell Förlag AB. 1984. p. 158.

- ^Taylor (2014),pp. 264–66.

- ^abcdefThe articleAlfkorsinNordisk familjebok(1904).

- ^"Novatoadvance, Chasing waterfalls... and elves".Novatoadvance.Retrieved14 June2012.

- ^"Icelandreview, Iceland Still Believes in Elves and Ghosts".Icelandreview. Archived fromthe originalon 6 December 2008.Retrieved14 June2012.

- ^Hafstein, Valdimar Tr.(2000)."The Elves' Point of ViewCultural Identity in Contemporary Icelandic Elf-Tradition"(PDF).Fabula.41(1–2): 87–104 (quoting p. 93).doi:10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.87.S2CID162055463.

- ^Hall (2015).

- ^Keightley (1850),p. 57.

- ^"elf-lock",Oxford English Dictionary,OED Online (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, 1989;"Rom. & Jul. I, iv, 90 Elf-locks" is the oldest example of the use of the phrase given by the OED.

- ^Tolkien, J. R. R., (1969) [1947], "On Fairy-Stories", inTree and Leaf,Oxford, pp. 4–7 (3–83). (First publ. inEssays Presented to Charles Williams,Oxford, 1947.)

- ^Thun, Nils (1969). "The Malignant Elves: Notes on Anglo-Saxon Magic and Germanic Myth".Studia Neophilologica.41(2): 378–96.doi:10.1080/00393276908587447.

- ^abGrimm (1883b),p. 443.

- ^"Die aufnahme des Wortes knüpft an Wielands Übersetzung von Shakespeares Sommernachtstraum 1764 und and Herders Voklslieder 1774 (Werke 25, 42) an";Kluge, Friedrich(1899).Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache(6th ed.). Strassbourg: K. J. Trübner. p.93.

- ^Grimm & Grimm (1854–1954),s.v.Elb.

- ^Taylor (2014),pp. 119–135.

- ^Erixon, Sigurd (1961), Hultkrantz, Åke (ed.), "Some Examples of Popular Conceptions of Sprites and other Elementals in Sweden during the 19th Century",The Supernatural Owners of Nature: Nordic Symposion on the Religious Conceptions of Ruling Spirits (genii locii, genii speciei) and Allied Concepts,Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion, 1, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, p. 34 (34–37)

- ^abcdHall (2014).

- ^Restad, Penne L. (1996).Christmas in America: A History.Oxford University Press. p. 147.ISBN978-0-19-510980-1.

- ^Belk, Russell W.(Spring 1987). "A Child's Christmas in America: Santa Claus as Deity, Consumption as Religion".The Journal of American Culture.10(1): 87–100 (p. 89).doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1987.1001_87.x.

- ^abcBergman (2011).

- ^Cooper, Victoria Elizabeth (2016).Fantasies of the North: Medievalism and Identity inSkyrim(PhD). University of Leeds.

- ^West (2007),pp. 294–5.

- ^West (2007),pp. 292–5, 302–3.

- ^Hall (2007),pp. 68, 138–40.

- ^Hall (2008).

- ^Henningsen (1990).

- ^Pócs (1989),p. 13.

- ^Leppälahti (2011),p. 170.

- ^Pócs (1989),p. 14.

- ^West (2007),pp. 292–5.

- ^"Mazapegul: il folletto romagnolo che ha fatto dannare i nostri nonni"[Mazapegul: The elf from Romagna who ruined our grandparents].Romagna Republic(in Italian). 21 November 2020.Retrieved1 March2024.

- ^Campagna, Claudia (28 February 2020)."Mazapegul, il folletto romagnolo"[Mazapegul, the romagnol elf].Romagna a Tavola(in Italian).Retrieved1 March2024.

- ^"Mazapègul, il 'folletto di Romagna' al Centro Mercato"[Mazapègul, the 'elf of Romagna' at the Market Centre].estense(in Italian). 13 March 2014.Retrieved2 March2024.

- ^Cuda, Grazia (5 February 2021)."E' Mazapégul"[It's Mazapégul].Il Romagnolo(in Italian).Retrieved2 March2024.

- ^E.g. Rossella Carnevali and Alice Masillo, 'A Brief History of Psychiatry in Islamic World',Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine,6–7 (2007–8) 97–101 (p. 97); David Frankfurter,Christianizing Egypt: Syncretism and Local Worlds in Late Antiquity(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), p. 50.

- ^Tzeferakos, Georgios A.; Douzenis, Athanasios I. (2017)."Islam, Mental Health and Law: A General Overview".Annals of General Psychiatry.16:28.doi:10.1186/s12991-017-0150-6.PMC5498891.PMID28694841.

- ^Hall (2006),p. 242.

- ^Harris (2005),p. 59.

- ^Scott, William Henry(1994).Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society.Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.ISBN978-971-550-135-4.

- ^Hadler, Jeffrey (9 October 2008).Muslims and Matriarchs: Cultural Resilience in Indonesia Through Jihad and... By Jeffrey Hadler.Cornell University Press.ISBN9780801446979.Retrieved23 June2012.

- ^Cowan, James(1925).Fairy Folk Tales of the Maori.New Zealand:Whitcombe and Tombs.

References

- Þorgeirsson, Haukur (2011)."Álfar í gömlum kveðskap"(PDF).Són(in Icelandic).9:49–61.[permanent dead link]

- Bergman, Jenni (2011).The Significant Other: A Literary History of Elves(PhD). University of Cardiff.

- Carlyle, Alexander, ed. (1788)."An Ode on the Popular Superstitions of the Highlands. Written by the late William Collins".Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.i:68.

- Dumézil, Georges(1973).Gods of the Ancient Northmen.University of California Press. p.3.ISBN978-0-520-02044-3.

- Edwards, Cyril (1994). Thomas, Neil (ed.).Heinrich von Morungen and the Fairy-Mistress Theme.Lewiston, N. Y.: Mellen. pp. 13–30.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Green, Richard Firth (2003). "Changing Chaucer".Studies in the Age of Chaucer.25:27–52.doi:10.1353/sac.2003.0047.S2CID201747051.

- Green, Richard Firth (2016).Elf Queens and Holy Friars: Fairy Beliefs and the Medieval Church.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Grimm, Jacob;Grimm, Wilhelm(1854–1954).Deutsches Wörterbuch.Leipzig: Hirzel.

- Grimm, Jacob(1835),Deutsche Mythologie.

- Grimm, Jacob (1883b)."XVII. Wights and Elves".Teutonic mythology.Vol. 2. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. pp. 439–517.

- Grimm, Jacob (1883c).Teutonic mythology.Vol. 3. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. pp. 1246ff.

- Grimm, Jacob (1888)."Supplement".Teutonic mythology.Vol. 4. Translated by James Steven Stallybrass. pp. 1407–1435.

- Gunnell, Terry (2007), Wawn, Andrew; Johnson, Graham; Walter, John (eds.),"How Elvish were the Álfar?"(PDF),Constructing Nations, Reconstructing Myth: Essays in Honour of T. A. Shippey,Making the Middle Ages, 9, Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 111–30

- Hall, Alaric Timothy Peter (2004).The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England(PDF)(PhD). University of Glasgow.

- Hall, Alaric (2005)."Getting Shot of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials"(PDF).Folklore.116(1): 19–36.doi:10.1080/0015587052000337699.S2CID53978130.Eprints.whiterose.ac.uk.

- Hall, Alaric (2006)."Elves on the Brain: Chaucer, Old English andElvish"(PDF).Anglia: Zeitschrift für Englische Philologie.124(2): 225–243.doi:10.1515/ANGL.2006.225.S2CID161779788.

- Hall, Alaric (2007).Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity.Boydell Press.ISBN978-1-84383-294-2.

- Hall, Alaric (February 2008)."Hoe Keltisch zijn elfen eigenlijk?"[How Celtic are the Fairies?].Kelten(in Dutch).37:2–5. Archived fromthe originalon 10 October 2017.Retrieved26 June2017.

- Hall, Alaric (2009).""Þur sarriþu þursa trutin": Monster-Fighting and Medicine in Early Medieval Scandinavia ".Asclepio: Revista de Historia de la Medicina y de la Ciencia.61(1): 195–218.doi:10.3989/asclepio.2009.v61.i1.278.PMID19753693.

- Hall, Alaric (2014), "Elves", in Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (ed.),The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters(PDF),Ashgate, archived fromthe original(PDF)on 12 December 2016,retrieved26 June2017

- Hall, Alaric (2015),Why aren't there any elves in Hellisgerði any more? Elves and the 2008 Icelandic Financial Crisis', working paper

- Harris, Ian Charles (2005),Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice,Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press

- Henderson, Lizanne; Cowan, Edward J. (2001).Scottish Fairy Belief: A History.East Linton: Tuckwell.

- Henningsen, Gustav (1990), "'The Ladies from Outside': An Archaic Pattern of the Witches' Sabbath'",in Ankarloo, Bengt; Henningsen, Gustav (eds.),Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries,Oxford University Press, pp. 191–215

- Ingwersen, Niels (1995). "The Need for Narrative: The Folktale as Response to History".Scandinavian Studies.67(1): 77–90.JSTOR40919731.

- Jakobsson, Ármann[in Icelandic](2006). "The Extreme Emotional Life of Völundr the Elf".Scandinavian Studies.78(3): 227–254.JSTOR40920693.

- Jakobsson, Ármann (2015). "Beware of the Elf! A Note on the Evolving Meaning ofÁlfar".Folklore.126(2): 215–223.doi:10.1080/0015587X.2015.1023511.S2CID161909641.

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1992)."Magic, Miracle, and Popular Practice in the Early Medieval West: Anglo-Saxon England".InNeusner, Jacob;Frerichs, Ernest S.; Flesher, Paul Virgil McCracken (eds.).Religion, Science, and Magic: In Concert and in Conflict.Oxford University Press. p. 172.ISBN978-0-19-507911-1.

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1996).Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context.Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.ISBN978-0-8078-2262-3.

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1998)."Elves in the Psalms? The Experience of Evil from a Cosmic Perspective".In Ferreiro, Alberto; Russell, Jeffrey Burton (eds.).The Devil, Heresy and Witchcraft in the Middle Ages: Essays in Honor of Jeffrey B. Russell.Cultures, Beliefs and Traditions. Vol. 6. Leiden: Brill. pp. 19–44.ISBN978-9-0041-0610-9.

- Karg-Gasterstädt, Elisabeth[in German];Frings, Theodor[in German](1968).Althochdeutsches Wörterbuch.Berlin.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Keightley, Thomas(1850) [1828].The Fairy Mythology.Vol. 1. H. G. Bohn.Vol.2

- Kuhn, Adalbert(1855)."Die sprachvergleichung und die urgeschichte der indogermanischen völker".Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Sprachforschung.4..

- Leppälahti, Merja[in Finnish](2011), "Meeting Between Species: Nonhuman Creatures from Folklore as Character of Fantasy Literature",Traditiones,40(3): 169–77,doi:10.3986/Traditio2011400312

- Motz, Lotte(1983).The Wise One of the Mountain: Form, Function and Significance of the Subterranean Smith. A Study in Folklore.Göppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik. Vol. 379. Göppingen: Kümmerle. pp. 29–37.ISBN9783874525985.

- Orel, Vladimir E.(2003).A Handbook of Germanic Etymology.Brill.ISBN978-90-04-12875-0.

- Pócs, Éva(1989),Fairies and Witches at the Boundary of South-Eastern and Central Europe,Helsinki: Folklore Fellows Communications 243

- Purkiss, Diane(2000).Troublesome Things: A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories.Allen Lane..

- Schrader, Otto(1890).Prehistoric Antiquities of the Aryan Peoples.Frank Byron Jevons (tr.). Charles Griffin & Company. p.163..

- Schulz, Monika (2000).Magie oder: Die Wiederherstellung der Ordnung.Beiträge zur Europäischen Ethnologie und Folklore, Reihe A: Texte und Untersuchungen. Vol. 5. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

- Scott, Walter(1803).Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.Vol. 2. James Ballantyne.

- Shippey, T. A.(2004)."Light-elves, Dark-elves, and Others: Tolkien's Elvish Problem".Tolkien Studies.1(1): 1–15.doi:10.1353/tks.2004.0015.

- Shippey, Tom(2005), "Alias oves habeo: The Elves as a Category Problem",The Shadow-Walkers: Jacob Grimm's Mythology of the Monstrous,Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 291 / Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, 14, Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies in collaboration with Brepols, pp. 157–187

- Spence, Lewis(1946).British Fairy Origins.Watts.

- Taylor, Lynda (2014).The Cultural Significance of Elves in Northern European Balladry(PhD). University of Leeds.

- Tolley, Clive (2009).Shamanism in Norse Myth and Magic.Folklore Fellows' Communications. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica. pp. 296–297, 2 volumes.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: postscript (link) - West, Martin Litchfield(2007),Indo-European Poetry and Myth,Oxford, England: Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-928075-9

Further reading

- Goodrich, Jean N. "Fairy, Elves and the Enchanted Otherworld". In:Handbook of Medieval CultureVolume 1. Edited by Albrecht Classen. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015. pp. 431-464.https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110267303-022