Guangxu Emperor

| Guangxu Emperor Quang Tự đế | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 25 February 1875 – 14 November 1908 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Tongzhi Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Xuantong Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Regent | Empress Dowager Ci'an(1875–1881) Empress Dowager Cixi(1875–1908) | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | 14 August 1871 ( cùng trị mười năm tháng sáu 28 ngày ) Prince Chun's Mansion,Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 14 November 1908(aged 37) ( Quang Tự 34 năm mười tháng 21 ngày ) Hanyuan Temple, Yingtai Island,Zhongnan Lakes,Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Chong Mausoleum,Western Qing tombs | ||||||||||||||||

| Consort | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Aisin-Gioro | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Qing | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Yixuan,Prince Chunxian of the First Rank | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Yehe-Nara Wanzhen | ||||||||||||||||

| Guangxu Emperor | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | Quang Tự đế | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Quang Tự đế | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

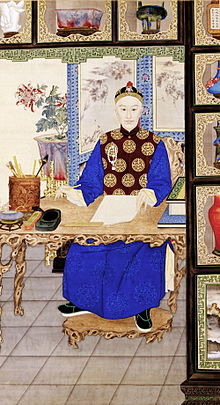

TheGuangxu Emperor(14 August 1871 – 14 November 1908),[1]also known by histemple nameEmperor Dezong of Qing,personal nameZaitian,[2]was the tenthemperorof theQing dynasty,[3]and the ninth Qing emperor to rule overChina proper.His reign was largely dominated by his maternal auntEmpress Dowager Cixi.He initiated the radicalHundred Days' Reformbut was abruptly stopped when the Empress Dowager launched a coup in 1898, after which he was held under virtualhouse arrestuntil his death.

Emperor Guangxu was the second son of Prince Chun, Yixuan (a son of the Daoguang Emperor), and his mother, Yehenara Wanzhen, was the sister ofEmpress Dowager Cixi.AfterEmperor Tongzhi's death in 1874, he was supported by the two Empress Dowagers (Ci'an and Cixi) to succeed the throne, being adopted at the age of three byEmperor Xianfengand the two Empress Dowagers, thereby inheriting the throne. During the early years of his reign, the two dowagers jointly handled state affairs. As Ci’an passed away in 1881, Cixi continued to act as the sole regent. In 1889, Guangxu got married and announced his personal rule. After the failure of theHundred Days’ Reformin 1898, he was confined by Cixi in theYingtaiPavilion ofZhongnanhai,completely losing his ruling power. In November 1908, he died ofarsenicpoisoning at Yingtai. He reigned for 34 years, dying at the age of 38 without leaving any descendants, and was buried in theChongling Mausoleumof the Western Qing Tombs.

The emperor’s life was turbulent and full of hardships. He was not originally the heir to the throne but was forcibly elevated after Emperor Tongzhi died without an heir. From a young age, he was forced to leave his home and enter the palace, where he was strictly controlled and disciplined by Cixi, enduring many hardships and sorrows. Even after he reached adulthood and began his personal rule, Cixi was unwilling to relinquish her control over state power, making him continue to be a puppet, unable to enjoy the majesty and power of a monarch. During his reign, the Qing dynasty became increasingly impoverished and weak. TheSino-French War,the First Sino-Japanese War,andthe Boxer Rebellionfollowed one after another, causing the dynasty to cede territory and pay indemnities, losing sovereignty and humiliating the nation, leaving the people in misery. Seeing the country’s decline, Guangxu allied with intellectuals to launch the Hundred Days’ Reform, attempting to save and rejuvenate the nation. However, this movement was immediately suppressed by the conservative forces led by Cixi, resulting in his confinement and loss of political power and personal freedom until his untimely death. His tragic fate is rare among emperors. Although historians do not deny the failures and limitations during his reign, he is still regarded as a relatively progressive and enlightened monarch of the dynasty. His image in historical research and literary works is also mostly positive.

Accession to the throne and upbringing

[edit]The emperor was the second son ofYixuan (Prince Chun),and his primary spouseYehenara Wanzhen,a younger sister ofEmpress Dowager Cixi.On 12 January 1875, Zaitian's cousin, theTongzhi Emperor,died without a son to succeed him. Breaking the imperial convention that a new emperor must always be of a generation after that of the previous emperor, candidates were considered from the generation of the Tongzhi Emperor.Empress Dowager Ci'ansuggested choosing one ofPrince Gong's sons to be the next emperor, but was overruled by her co-regent, Empress Dowager Cixi. Instead, Cixi nominated Zaitian (her nephew) and the imperial clan eventually agreed with her choice because Zaitian was younger than other adoptable children of the same generation.

Zaitian was named heir and successor to his late uncle, theXianfeng Emperor,rather than his cousin and predecessor, theTongzhi Emperor,so as to maintain the father-son succession law. He ascended to the throne at the age of four and adopted "Guangxu" as hisregnal name,therefore he is known as the "Guangxu Emperor". He was adopted by Empress Dowager Cixi and Ci'an. Cixi remained as regent under the title "Holy Mother, Empress Dowager" ( thánh mẫu Hoàng Thái Hậu ) while her co-regent Empress Dowager Ci'an was called "Mother Empress, Empress Dowager" ( mẫu hậu Hoàng Thái Hậu ).

Beginning in 1876, the Guangxu Emperor was taught byWeng Tonghe,who had also been involved in the disastrous upbringing of the Tongzhi Emperor yet somehow managed to be exonerated of all possible charges.[4]Weng instilled in the Guangxu Emperor a duty of filial piety toward the Empress Dowagers Cixi and Ci'an.[5]

In 1881, when the Guangxu Emperor was nine, Empress Dowager Ci'an died unexpectedly, leaving Empress Dowager Cixi as sole regent for the boy. In Weng's diaries during those days, Guangxu was reportedly seen with swollen eyes, had poor concentration and was seeking consolation from Weng. Weng too expressed his concern that Cixi was the one who had been suffering from chronic ill health, not Ci'an. During this time, the imperialeunuchsoften abused their influence over the boy emperor.[6]The Guangxu Emperor had also reportedly begun to hold some audiences on his own as an act of necessity.[7]

Taking over the reins of power

[edit]

In 1887, the Guangxu Emperor was old enough to begin to rule in his own right, but the previous year, several courtiers, includingPrince ChunandWeng Tonghe,had petitioned Empress Dowager Cixi to postpone her retirement from the regency. Despite Cixi's agreement to remain as regent, by 1886 the Guangxu Emperor had begun to write comments onmemorials to the throne.[7]In the spring of 1887, he partook in his first field-plowing ceremony, and by the end of the year he had begun to rule under Cixi's supervision.

Eventually, in February 1889, in preparation for Cixi's retirement, the Guangxu Emperor was married. Much to the emperor's dislike, Cixi selected her niece, Jingfen, to be empress. She became known asEmpress Longyu.She also selected a pair of sisters, who became ConsortsJinandZhen,to be the emperor's concubines. The following week, with the Guangxu Emperor married, Cixi retired from the regency.

Years in power

[edit]

Even after the Guangxu Emperor began formal rule, Empress Dowager Cixi continued to influence his decisions and actions, despite residing several months of the year at theSummer Palace.Weng Tonghe reportedly observed that while the emperor attended to day-to-day state affairs, in more difficult cases the emperor and theGrand Councilsought Cixi's advice.[8]In fact, the emperor often journeyed to the Summer Palace to pay his respects to his aunt and to discuss state affairs with her.

In March 1891, the Guangxu Emperor received the foreign ministers to China at an audience in the "Pavilion of Purple Light", in what is now part ofZhongnanhai,something that had also been done by the Tongzhi Emperor in 1873. That summer, under pressure from theforeign legationsand in response to revolts in the Yangtze River valley that were targeting Christian missionaries, the emperor issued an edict ordering Christians to be placed under state protection.[9]

The Guangxu Emperor, while growing up, apparently had been instilled with the importance of frugality. In 1892, he tried to implement a series of draconian measures to reduce expenditures by theImperial Household Department,which proved to be one of his few administrative successes.[10]But it was only a partial victory, as he had to approve higher expenditures than he would have liked to meet Cixi's needs.

The summer of 1894 saw the outbreak of theFirst Sino-Japanese Warover influence in Korea.[11]The Emperor was reportedly eager for the war against Japan, and became associated with the pro-war faction in the imperial court, which believed that China would easily win. This was in contrast to the Empress Dowager and ViceroyLi Hongzhang,who both wanted to reach a peaceful resolution.[12]In September 1894, after the major defeat of the Chinese land forces at thebattle of Pyongyangand the naval forces at theYalu River,the Guangxu Emperor wanted to leave the capital and go to the front lines to personally take command of the troops, but he was talked out of it by his advisors.[13]The emperor met with a German military advisor to the Qing navy, Constantin von Hanneken, who had been present at the battle of the Yalu, to learn what exactly happened.[14]He also signed edicts calling for the execution of generals who were defeated.[12]In February 1895, as peace negotiations with the Japanese were underway, the Guangxu Emperor spoke with his top negotiator before he met with the Japanese, Li Hongzhang, and allegedly told him during their conversation that China needed large scale reforms.[15]

During the war, even though the Guangxu Emperor was nominally the sovereign ruler of the Qing Empire, officials often ignored him and instead sent theirmemorialsto Cixi for her approval.[16]Eventually, two sets of Grand Council memoranda were created, one for the emperor and the other for the empress dowager, a practice that continued until it was rendered unnecessary by the events in the autumn of 1898. Following the Qing Empire's defeat and forced agreement to the terms of theTreaty of Shimonoseki,the Guangxu Emperor reportedly expressed his wish to abdicate.[17]In April 1895, after the Treaty of Shimonoseki was negotiated and signed, but before its ratification by the Qing government, its terms were publicized. Government bureaucrats throughout the empire urged the imperial court to reject it and continue fighting. The Emperor did not want to take responsibility for ratifying the treaty, and neither did the Empress Dowager, who may have wanted to use the defeat against Japan to undermine his influence. He tried to shift the responsibility in an edict by asking two officials,Liu KunyiandWang Wenshao,to give a recommendation on whether to ratify treaty, because they had told him that the Chinese army was capable of achieving victory. Eventually, the emperor ratified it.[18]

The emperor and the Qing government faced further humiliation in late 1897 when theGerman Empireused the murders of two priests inShandong Provinceas an excuse to occupyJiaozhou Bay,prompting a "scramble for concessions" by other foreign powers. After this incident, the emperor wrote an edict in December 1897 that asked bureaucrats with military knowledge to recommend reforms that could be made.[19]

Following the war and the scramble for concessions, the Guangxu Emperor came to believe that by learning from constitutional monarchies like Japan, the Qing Empire would become more politically and economically powerful. In June 1898, the emperor began theHundred Days' Reform,aimed at a series of sweeping political, legal and social changes. For a brief time, after Cixi's supposed retirement, the Guangxu Emperor issued edicts for a massive number of far-reaching modernizing reforms with the help of more progressive officials such asKang YouweiandLiang Qichao.

Changes ranged from infrastructure to industry and thecivil examination system.The Guangxu Emperor issued decrees allowing the establishment of a modern university in Beijing, the construction of the Lu-Han railway, and a system of budgets similar to that of Western governments. The initial goal was to make China a modern constitutional empire, but still within the traditional framework, as with Japan'sMeiji Restoration.

The reforms, however, were not only too sudden for a China still under significantneo-Confucianinfluence and other elements oftraditional culture,but also came into conflict with Cixi, who held real power. Many officials, deemed useless and dismissed by the Guangxu Emperor, begged her for help. Although Cixi did nothing to stop the Hundred Days' Reform from taking place, she knew the only way to secure her power base was to stage a military coup. The Guangxu Emperor became aware of such a plan, so he asked Kang Youwei and his reformist allies to plan his rescue. They decided to use the help ofYuan Shikai,who had a modernized army, albeit only 6,000-strong. Cixi relied onRonglu's army in Tianjin.

Ronglu also had an ally, GeneralDong Fuxiang,who commanded 10,000 MuslimKansu Braves,including generals such asMa FuxiangandMa Fulu,stationed in the Beijing metropolitan area. Armed with more advanced firearms and artillery, they sided with Cixi's conservative faction during the coup.[22][23]

The day before thestaged coupwas supposed to take place, Yuan Shikai revealed everything to Ronglu, exposing the Guangxu Emperor's plans. This gained Yuan Shikai the trust of Cixi, as well as the status of lifetime enemy of the Guangxu Emperor as well as the emperor's younger half-brother,Zaifeng.Following the exposure of the plot, the emperor and empress dowager met, and the emperor retreated to the Yingtai Pavilion, a palace on a lake that is now part of theZhongnanhai Compound.

Lei Chia-sheng ( Lôi gia thánh ), a Taiwanese history professor, proposes an alternative view: that the Guangxu Emperor might have been led into a trap by the reformists led byKang Youwei,who in turn was in Lei's opinion tricked by British missionaryTimothy Richardand former Japanese prime ministerItō Hirobumiinto agreeing to appoint Itō as one of many foreign advisors.[24]British ambassadorClaude MacDonaldclaimed that the reformists had actually "much injured" themodernizationof China.[25]Lei claims that Cixi learned of the plot and decided to put an end to it to prevent China from coming under foreign control.[26]

Under house arrest after 1898

[edit]

The Guangxu Emperor's duties after 1898 became rather limited. The emperor was effectively removed from power as emperor (despite keeping the title), but he did retain some status.[citation needed]

The emperor was kept informed of state affairs, reading them with Cixi prior to audiences,[27]and was also present at audiences, sitting on a stool to Cixi's left hand while Cixi occupied the main throne. He discharged his ceremonial duties, such as offering sacrifices during ceremonies, but never ruled alone again.

In 1898, shortly after the collapse of theHundred Days' Reform,the Guangxu Emperor's health began to decline, prompting Cixi to name Pujun, a son of the emperor's cousin, the reactionaryPrince Duan,as heir presumptive. Pujun and his father were removed from their positions after theBoxer Rebellion.He was examined by a physician at the French Legation and diagnosed with chronicnephritis;he was also discovered to be impotent at the time.

During theBoxer Rebellion,Emperor Guangxu fiercely opposed the idea of using usurpers as a means to counter foreign invasion. His letter to thenUnited StatespresidentTheodore Rooseveltis still preserved in U.S. government archives. On 14 August 1900, the Guangxu Emperor, along with Cixi, Empress Longyu and some other court officials, fled from Beijing as the forces of theEight-Nation Alliancemarched on the capital to relieve the legations that had been besieged during theBoxer Rebellion.

Returning to the capital in January 1902, after the withdrawal of the foreign powers, the Guangxu Emperor spent the next few years working in his isolated palace withwatchesandclocks,which had been a childhood fascination, some say in an effort to pass the time until Cixi's death. He also read widely and spent time learning English from Cixi's Western-educated lady-in-waiting,Yu Deling.His relationship withEmpress Longyu,Cixi's niece (and the Emperor's own first cousin), also improved to some extent.

Death

[edit]The Guangxu Emperor died on 14 November 1908, a day before Cixi's death, at the age of 37. For a long time there were several theories about the emperor's death, none of which was accepted fully by historians. Most were inclined to believe that Cixi, herself very ill, poisoned the Guangxu Emperor because she was afraid he would reverse her policies after her death.China Dailyquoted a historian,Dai Yi,who speculated that Cixi might have known of her imminent death and worried that the Guangxu Emperor would continue his reforms after her death.[28]Another theory is that the Guangxu Emperor was poisoned byYuan Shikai,who knew that if the emperor were to come to power again, Yuan would likely be executed for treason.[29]There were no reliable sources to prove who murdered the Guangxu Emperor.

The medical records kept by the Guangxu Emperor's physician show the emperor suffered from "spells of violent stomachaches" and that his face had turned blue, typical symptoms ofarsenicpoisoning.[29]To dispel persistent rumors that the emperor had been poisoned, the Qing imperial court produced documents and doctors' records suggesting that the Guangxu Emperor died from natural causes, but these did not allay suspicion.

On 4 November 2008, forensic tests revealed that the level of arsenic in the emperor's remains was 2,000 times higher than that of ordinary people. Scientists concluded that the poison could only have been administered in a high dose at one time.[30]

The Guangxu Emperor was succeeded by Cixi's choice as heir, his nephewPuyi,who took theregnal name"Xuantong". In January 1912, the Guangxu Emperor's consort, who had becomeEmpress Dowager Longyu,placed her seal on theabdication decree,ending two thousand years of imperial rule in China. Longyu died childless in 1913.

After theXinhai Revolutionof 1911–1912, theChinese Republicfunded the construction of the Guangxu Emperor's mausoleum in theWestern Qing Tombs.The tomb was robbed during theChinese Civil Warand the underground palace (burial chamber) is now open to the public.

Appraisal

[edit]In 1912,Sun Yat-senpraised the Guangxu Emperor for his educational reform package that allowed China to learn more aboutWestern culture.After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, historian Fan Wenlan ( phạm văn lan ) called the Guangxu Emperor "a Manchu noble who could accept Western ideas". Some historians[who?]believe that the Guangxu Emperor was the first Chinese leader to implement modernizing reforms and capitalism. Imperial power in the Qing dynasty saw itsnadirunder Guangxu, and he was the only Qing emperor to have been put under house arrest during his own reign.

Honours

[edit]| Styles of Guangxu Emperor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | Son of Heaven ( thiên tử ) |

Domestic honours

- Sovereign of the Order of the Peacock Feather

- Sovereign of the Order of the Blue Feather

- Sovereign of theOrder of the Double Dragon

Foreign honours[citation needed]

Belgium:Grand Cordon of theOrder of Leopold(military),18 July 1898[31]

Belgium:Grand Cordon of theOrder of Leopold(military),18 July 1898[31] German Empire:Knight of theOrder of the Black Eagle,in Diamonds,28 June 1898[32]

German Empire:Knight of theOrder of the Black Eagle,in Diamonds,28 June 1898[32] Kingdom of Hawaii:Knight Grand Cross of theOrder of Kamehameha I,1882

Kingdom of Hawaii:Knight Grand Cross of theOrder of Kamehameha I,1882 Empire of Japan:Grand Cordon of theOrder of the Chrysanthemum,29 April 1899[33]

Empire of Japan:Grand Cordon of theOrder of the Chrysanthemum,29 April 1899[33] Kingdom of Portugal:Grand Cross of theSash of the Three Orders,1904

Kingdom of Portugal:Grand Cross of theSash of the Three Orders,1904 Russian Empire:Order of St. Andrew

Russian Empire:Order of St. Andrew

Family

[edit]

The Guangxu Emperor had one empress and two consorts in total. The emperor was forced byEmpress Dowager Cixito marry her niece (his cousin)Jingfen,who was two years his senior. Jingfen's father, Guixiang (Cixi's younger brother), and Cixi selected her to be the Guangxu Emperor's wife in order to strengthen the power of their own family. After the marriage, Jingfen was made empress and was granted the honorific title of "Longyu" (Long dụ;lit. 'auspicious and prosperous') after the death of her husband. However, the Guangxu Emperor detested his wife, and spent most of his time with hisfavoriteconcubine,Consort Zhen(better known as the "Pearl Consort" ). Rumors allege that in 1900, Consort Zhen was drowned by being thrown into a well on Cixi's order after she begged Empress Dowager Cixi to let the Guangxu Emperor stay in Beijing for negotiations with the foreign powers. That incident happened when the Imperial Family was preparing to leave theForbidden Citydue to the occupation of Beijing by theEight-Nation Alliancein 1900. Like his predecessor, theTongzhi Emperor,the Guangxu Emperor died without issue. After his death in 1908, Empress Dowager Longyu ruled in cooperation withZaifeng.

Empress

- Empress Xiaodingjing( hiếu định cảnh Hoàng Hậu ) of theYehe-Nara clan( Diệp Hách Na Lạp thị; 28 January 1868 – 22 February 1913), personal nameJingfen( tĩnh phân )[a]

Imperial Noble Consort

- Imperial Noble Consort Wenjing( ôn tĩnh hoàng quý phi ) of theTatara clan( hắn hắn kéo thị; 6 October 1873 – 24 September 1924)

- Imperial Noble Consort Keshun( khác thuận hoàng quý phi ) of theTatara clan( hắn hắn kéo thị; 27 February 1876 – 15 August 1900)

Ancestry

[edit]| Jiaqing Emperor(1760–1820) | |||||||||||||||

| Daoguang Emperor(1782–1850) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaoshurui(1760–1797) | |||||||||||||||

| Yixuan(1840–1891) | |||||||||||||||

| Lingshou (1788–1824) | |||||||||||||||

| Imperial Noble Consort Zhuangshun(1822–1866) | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Weng | |||||||||||||||

| Guangxu Emperor (1871–1908) | |||||||||||||||

| Jingrui | |||||||||||||||

| Huizheng (1805–1853) | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Gūwalgiya | |||||||||||||||

| Wanzhen(1841–1896) | |||||||||||||||

| Huixian | |||||||||||||||

| Lady Fuca | |||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Family tree of Chinese monarchs (late)

- First Sino-Japanese War

- Boxer Rebellion

- List of unsolved murders

Notes

[edit]- ^First cousin of the Guangxu Emperor.

References

[edit]- ^"Arsenic killed Chinese emperor, reports say".cnn.Retrieved2019-11-11.

- ^"Qing Emperor Guangxu".travelchinaguide.Retrieved2019-11-11.

- ^"Guangxu | emperor of Qing dynasty".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2019-11-11.

- ^Kwong, Luke S.K. A Mosaic of the Hundred Days: Personalities, Politics and Ideas of 1898 (Harvard University Press, 1984), p. 45

- ^Kwong, pp. 52 & 53

- ^Kwong, pp. 47 & 48

- ^abKwong, p. 54

- ^Kwong, pp. 26 & 27

- ^Seagrave, SterlingDragon Lady: the Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China(Knopf, 1992), p. 291

- ^Kwong, p. 56

- ^Paine 2003,pp. 136–137.

- ^abPaine 2003,pp. 126–129.

- ^Paine 2003,p. 216.

- ^Paine 2003,pp. 187–188.

- ^Paine 2003,pp. 258–259.

- ^Kwong, p. 27

- ^Seagrave, p. 186

- ^Paine 2003,pp. 273–277.

- ^Rhoads 2000,p. 63.

- ^"Guangxu Emperor Quang Tự đế China 19th Century illustration".Historum.11 September 2020.

- ^Baranov, Alexey Mikhailovich (1905–1910).Materials on Manchuria, Mongolia, China and Japan.Harbin: Publishing house of the headquarters of the Zaamur district of the border service.

- ^Ann Heylen (2004).Chronique du Toumet-Ortos: looking through the lens of Joseph Van Oost, missionary in Inner Mongolia (1915–1921).Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 203.ISBN90-5867-418-5.Retrieved2010-06-28.

- ^Patrick Taveirne (2004).Han-Mongol encounters and missionary endeavors: a history of Scheut in Ordos (Hetao) 1874–1911.Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. p. 514.ISBN90-5867-365-0.Retrieved2010-06-28.

- ^Richard, Timothy,Forty-five Years in China: Reminiscencespubl.Frederick A. Stokes(1916)

- ^Correspondence Respecting the Affairs of China, Presented to Both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty(London, 1899.3), No. 401, p. 303.

- ^Lei Chia-sheng Lôi gia thánh,Liwan kuanglan: Wuxu zhengbian xintanNgăn cơn sóng dữ: Mậu Tuất chính biến tân thăm [Containing the furious waves: a new view of the 1898 coup], Taipei: Wanjuan lou vạn cuốn lâu, 2004.

- ^Derling, PrincessTwo Years in the Forbidden City, (New York: Moffat Yard & Company,pp. 69–70 (New York: Moffat Yard & Company, 1911), accessed June 25, 2013http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/DerYear.html

- ^"Arsenic killed Chinese emperor, reports say".CNN. 4 November 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 8 August 2012.Retrieved9 October2011.

- ^abMu, Eric.Reformist Emperor Guangxu was Poisoned, Study Confirms "Archived2015-05-09 at theWayback Machine.Danwei.3 November 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^"Arsenic killed Chinese emperor, reports say".CNN.2008-11-04.Retrieved2022-06-10.

- ^"Liste des Membres de l'Ordre de Léopold",Almanach Royale Belgique(in French), Bruxelles, 1899, p.72– via hathitrust.org

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"Schwarzer Adler-orden",Königlich Preussische Ordensliste(in German), Berlin, 1895, p.5– via hathitrust.org

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Hình Bộ phương tắc (2017).Minh trị thời đại の huân chương ngoại giao nghi lễ(PDF)(in Japanese). Minh trị thánh đức kỷ niệm học được kỷ yếu. p. 149.

Bibliography

[edit]- Paine, S.C.M (2003).The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-81714-1.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000).Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928.Seattle: University of Washington Press.ISBN978-0-295-99748-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Hudson, James J. "A Game of Thrones in China: The Case of Cixi, Empress Dowager of the Qing Dynasty (1835–1908)." inQueenship and the Women of Westeros(Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020) pp. 3–27.[ISBN missing]

- Rawski, Evelyn S.The last emperors: A social history of Qing imperial institutions(Univ of California Press, 1998).[ISBN missing]

- Hummel, Arthur W. Sr.,ed. (1943)..Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period.United States Government Printing Office.

External links

[edit]- Scholarly studies

Media related toGuangxu Emperorat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toGuangxu Emperorat Wikimedia Commons

- 1870s in China

- 1871 births

- 1880s in China

- 1890s in China

- 1900s in China

- 1908 deaths

- 1908 murders in China

- 19th-century Chinese monarchs

- 20th-century Chinese monarchs

- 20th-century murdered monarchs

- 20th-century murders in China

- Child monarchs from Asia

- Chinese dissidents

- Chinese people of the Boxer Rebellion

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Aviz

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Christ (Portugal)

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint James of the Sword

- Murdered emperors of China

- Murdered royalty

- Emperors of the Qing dynasty

- Unsolved murders in China

- Deaths by arsenic poisoning

- People from Beijing