Ernst Chain

Sir Ernst Chain | |

|---|---|

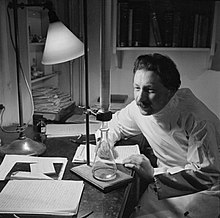

Chain in 1945 | |

| Born | Ernst Boris Chain 19 June 1906 |

| Died | 12 August 1979(aged 73) Castlebar,County Mayo,Ireland |

| Citizenship | German (until 1939) British (from 1939) |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Discovery of penicillin |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3[1] |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine(1945) Fellow of the Royal Society(1948) Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize(1954) Knight Bachelor(1969) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry |

| Institutions | Imperial College London University of Cambridge University of Oxford Istituto Superiore di Sanità University College Hospital |

Sir Ernst Boris ChainFRSFRSA[2](19 June 1906 – 12 August 1979) was a German-born British biochemist and co-recipient of theNobel Prize in Physiology or Medicinefor his work onpenicillin.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Life and career[edit]

Chain was born in Berlin, the son of Margarete (néeEisner) and Michael Chain, a chemist and industrialist dealing in chemical products.[13][14]His family was of bothSephardicandAshkenazi Jewishdescent. His father emigrated from Russia to study chemistry abroad and his mother was from Berlin.[15]In 1930, he received his degree inchemistryfromFriedrich Wilhelm University.His father descends fromZerahiah ben Shealtiel Ḥenwho was a prominent figure among theCatalonian Jewryand whose ancestors were leadingJewish figures in Babylonia.[16]He was a lifelong friend of ProfessorAlbert Neuberger,whom he met in Berlin in the 1930s.

After theNaziscame to power, Chain understood that, being Jewish, he would no longer be safe in Germany. He left Germany and moved to England, arriving on 2 April 1933 with £10 in his pocket. Geneticist and physiologistJ. B. S. Haldanehelped him obtain a position atUniversity College Hospital,London.

After a couple of months he was accepted as a PhD student atFitzwilliam College, Cambridge,where he began working onphospholipidsunder the direction of SirFrederick Gowland Hopkins.In 1935, he accepted a job atOxford Universityas a lecturer inpathology.During this time he worked on a range of research topics, includingsnake venoms,tumourmetabolism,lysozymes,andbiochemistrytechniques. Chain wasnaturalisedas aBritish subjectin April 1939.[17]

In 1939, he joinedHoward Floreyto investigate natural antibacterial agents produced bymicroorganisms.This led him and Florey to revisit the work ofAlexander Fleming,who had describedpenicillinnine years earlier. Chain and Florey went on to discover penicillin's therapeutic action and its chemical composition. Chain and Florey discovered how to isolate and concentrate the germ-killing agent in penicillin. For this research, Chain, Florey, and Fleming received the Nobel Prize in 1945.

Along withEdward Abrahamhe was also involved in theorising the beta-lactam structure of penicillin in 1942,[18]which was confirmed byX-ray crystallographydone byDorothy Hodgkinin 1945. Towards the end of World War II, Chain learned his mother and sister had been killed by the Nazis. After World War II, Chain moved to Rome, to work at theIstituto Superiore di Sanità(Superior Institute of Health). He returned to Britain in 1964 as the founder and head of the biochemistry department atImperial College London,where he stayed until his retirement, specialising infermentation technologies.[19]

On 17 March 1948 Chain was appointed aFellow of the Royal Society.

In spite of his successful scientific career and widespread recognition from his Nobel Prize, Chain was for some time barred from entry to the United States under theMcCarran Internal Security Actof 1950, being declined a visa on two occasions in 1951.[20]

In 1948, he marriedAnne Beloff,sister ofRenee Beloff,Max Beloff,John BeloffandNora Beloff,and a biochemist of significant standing herself. In his later life, his Jewish identity became increasingly important to him. Chain was an ardent Zionist and he became a member of the board of governors of theWeizmann Institute of ScienceatRehovotin 1954, and later a member of the executive council. He raised his children securely within the Jewish faith, arranging much extracurricular tuition for them. His views were expressed most clearly in his speech 'Why I am a Jew' given at the World Jewish Congress Conference of Intellectuals in 1965.[3]

Chain was appointedKnight Bachelorin the1969 Birthday Honours.[21]

Chain died in 1979 at theMayo General HospitalinCastlebar,Ireland. TheImperial College Londonbiochemistry building is named after him,[19]as is a road inCastlebar.[15]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"New Scientist".New Scientist Careers Guide: The Employer Contacts Book for Scientists.Reed Business Information: 51. 16 January 1986.ISSN0262-4079.[permanent dead link]

- ^Abraham, Edward(1983). "Ernst Boris Chain. 19 June 1906 – 12 August 1979".Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society.29:42–91.doi:10.1098/rsbm.1983.0003.JSTOR769796.

- ^abE. P. Abraham (2004). "'Chain, Sir Ernst Boris (1906–1979) ".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30913.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^Shampo, M. A.; Kyle, R. A. (2000)."Ernst Chain--Nobel Prize for work on penicillin".Mayo Clinic Proceedings.75(9): 882.doi:10.4065/75.9.882.PMID10994820.

- ^Raju, T. N. (1999). "The Nobel chronicles. 1945: Sir Alexander Fleming (1881-1955); Sir Ernst Boris Chain (1906-79); and Baron Howard Walter Florey (1898-1968)".Lancet.353(9156): 936.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75055-8.PMID10094026.S2CID54397485.

- ^Notter, A. (1991). "The difficulties of industrializing penicillin (1928-1942) (Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey, Ernst Boris Chain)".Histoire des Sciences Médicales.25(1): 31–38.PMID11638360.

- ^Abraham, E. P. (1980)."Ernst Chain and Paul Garrod".The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.6(4): 423–424.doi:10.1093/jac/6.4.423.PMID7000741.

- ^Mansford, K. R. (1979)."Sir Ernst Chain, 1906-1979".Nature.281(5733): 715–717.Bibcode:1979Natur.281..715M.doi:10.1038/281715a0.PMID399328.

- ^Abraham, E. P. (1979)."Obituary: Sir Ernst Boris Chain".The Journal of Antibiotics.32(10): 1080–1081.doi:10.7164/antibiotics.32.1087.PMID393682.

- ^"Sir Ernst Chain".British Medical Journal.2(6188): 505. 1979.PMC1595985.PMID385104.

- ^"Ernst Boris Chain".Lancet.2(8139): 427–428. 1979.doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90449-5.PMID89493.S2CID208792351.

- ^Wagner, W. H. (1979). "In memoriam, Dr. Ernst Boris Chain".Arzneimittel-Forschung.29(10): 1645–1646.PMID391241.

- ^"Ernst B. Chain".Nobel Foundation. 2013.Retrieved17 July2013.

- ^Forder, Arderne A. (1984).The more ye mow us down the more we grow: antibiotics in perspective.University of Cape Town.ISBN9780799209501.

- ^ab"Who was Sir Ernst Chain?".Connaught Telegraph. 6 October 2017.Retrieved18 May2019.

- ^Eliezer Laine and Zalman Berger, Avnei Chein - Toldot Mishpachat Chein, Brooklyn, New-York, 2004.Amazon link to book info

- ^"No. 34622".The London Gazette(Supplement). 5 May 1939. p. 2989.

- ^Jones, David S.; Jones, John H. (1 December 2014)."Sir Edward Penley Abraham CBE. 10 June 1913 – 9 May 1999".Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society.60:5–22.doi:10.1098/rsbm.2014.0002.ISSN0080-4606.

- ^abMartineau, Natasha (5 November 2012)."Sir Ernst Chain is honoured in building naming ceremony".Imperial College London.Retrieved17 July2013.

- ^"No Admission".The New York Times.9 December 1951.ProQuest111905452.

- ^"No. 44894".The London Gazette.11 July 1969. p. 7213.

Bibliography[edit]

- Medawar, Jean; Pyke, David (2012).Hitler's Gift: The True Story of the Scientists Expelled by the Nazi Regime(Paperback). New York: Arcade Publishing.ISBN978-1-61145-709-4.

External links[edit]

- Ernst Chainon Nobelprize.orgincluding the Nobel Lecture, 20 March 1946The Chemical Structure of the Penicillins

- Weintraub, B. (August 2003)."Ernst Boris Chain (1906–1979) and Penicillin".Chemistry in Israel(13). Israel Chemical Society: 29–32.

- Ernst ChainatFind a Grave

- 1906 births

- 1979 deaths

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- British Nobel laureates

- Academics of Imperial College London

- Fellows of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge

- 20th-century German chemists

- Jewish chemists

- Jewish creationists

- Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United Kingdom

- Jewish Nobel laureates

- Knights Bachelor

- People of Sephardic-Jewish descent

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- British people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Beloff family

- Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun, 2nd class

- British expatriates in Italy

- Physicians of the Charité

- Jewish British scientists