Etrog

Etrog(Hebrew:אֶתְרוֹג,plural:etrogim;Ashkenazi Hebrew:esrog,plural:esrogim) is the yellowcitronorCitrus medicaused by Jews during the week-long holiday ofSukkotas one of thefour species.Together with thelulav,hadass,andaravah,theetrogis taken in hand and held or waved during specific portions of the holiday prayers. Special care is often given to selecting anetrogfor the performance of the Sukkot holiday rituals.[1]

Etymology

[edit]Theromanization of the HebrewasetrogfromSephardi Hebrewis widely used. TheAshkenazi Hebrewpronunciation isesrogoresrig.It has beentransliteratedasetrogorethrogin scholarly works.[2]The Hebrew word is thought to derive from thePersianname for the fruit,wādrang,which first appears in theVendidad.[3]Related words are Persianturunj(ترنج) and Aramaicאַתְרוּגָּאʾaṯruggā.[4]It has also made its way intoArabicasأُتْرُجَّةِutrujjahnotably in ahadithcollected in theSahih Muslim.[5][6]A rare Aramaic form,etronga(אתרונגא), is significant because it retains thealveolar nasalsound (as indicated by thenun) ofwādrang,also observable in the English word 'orange'.[7]

Taxonomy

[edit]| Citronvarieties |

|---|

|

| Acidic-pulp varieties |

| Non-acidicvarieties |

| Pulpless varieties |

| Citronhybrids |

| Related articles |

InModern Hebrew,etrogis the name for anyvarietyor form of citron, whether kosher for the ritual or not. In general usage, though, the word is often reserved to refer only to those varieties and specimens used ritually as one of thefour species.Sometaxonomicexperts, likeHodgsonand others, have mistakenly treatedetrogas onespecific varietyof citron.[8][9]The variousJewish ritesutilize different varieties, according to their tradition or the decision of their respectiveposek.

Biblical references

[edit]On the first day you shall take the fruit of majestic trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God for seven days.

— Leviticus23:40, New Revised Standard Version

While the biblical phraseperi eitz hadar(פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר) (translated above as "fruit of majestic trees" ) may be interpreted or translated in a number of ways, theTalmudderives that the phrase refers to the etrog.

In modern Hebrew,hadarrefers to the genusCitrus.Nachmanides(1194 – c. 1270) suggests that the word was the original Hebrew name for the citron.[citation needed]According to this view, the wordetrogwas introduced over time and adapted fromAramaic.TheArabicname for the citron fruit,itranj(اترنج), mentioned inhadithliterature, is also adapted from Aramaic.

Historical cultivation

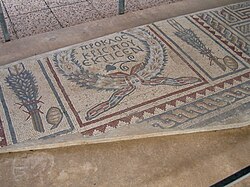

[edit]Etrogimwere extensively cultivated in theHoly Landat the time of theSecond Temple,and images ofetrogimare found at many archaeological sites of that era, including mosaics at theMaon Synagogue,Beth AlphaSynagogue, andHamat TiberiasSynagogue. At all of those sites, theetrogis depicted alongside other important religious symbols, like theshofarormenorah.Theetrogis also found on numerousBar Kokhba coins.

Archaeological evidence for Citrus fruits is limited, as neither seeds nor pollen are likely to be routinely recovered in archaeology.[10]The earliest evidence ofetrogimin Israel is the 2012 discovery of citron pollen from the second century BCE in excavations at theRamat Rachelsite.[11]

In diaspora

[edit]After thefall of Jerusalem in 70 CE,exiled Jews planted citron orchards wherever the climate allowed: in Southern Europe (Spain,Greece,andItaly) as well as in North Africa andAsia Minor.Jews who settled north of the warmer citron-growing areas depended on importedetrogim,which caused much anxiety given the dangers and uncertainties of sea travel. By the seventeenth century, some of the most popular sources foretrogimwere the islands ofCorsicaandCorfu.[citation needed]

Since the late 1850s, theFruit of the Goodly Tree AssociationinMandatory Palestinerepresentedetrogfarmers who marketed their crops to Jews in Europe. Some Jewish communities still preferred citrons from Italy, Greece, Morocco, or Yemen, but many Jews seeking citrons turned back toEretz Yisrael,theland of Israel.

American Jews continue to import the majority of their holidayetrogimfromIsrael,except duringshmitawhen there arehalachiccomplications in exporting the produce of Israel. The only commercial grower of etrogs in the United States is John Kirkpatrick, the former chairman of the Citrus Research Board, on a ranch in the town ofExeterin theSan Joaquin Valleyof California. Kirkpatrick, who is not Jewish, began growing etrogs in 1980 following a phone call with Yisroel Weisberger, an employee at a Judaica store in Brooklyn. In 1995, Weisberger's brother, Yaakov Shlomo Rothberg, became involved in the operation and has since become Kirkpatrick's business partner. As of 2010[update],Kirkpatrick has 250 etrog trees and produces 3,000 suitable etrogs per year, with 9,000 that do not qualify due to halakhic requirements.[12]While there are other growers in California, such as Inga Dorosz and David Sleeth in the town ofGordanear Big Sur, these are not rabbinically supervised and are therefore not kosher.[13]

Cosmetic requirements

[edit]Pitam

[edit]

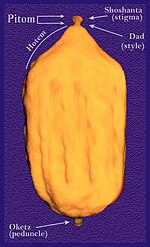

Apitamorpitom(Hebrew:פיטום; pluralpitamim) is composed of a style (Hebrew: "דַד "dad), and astigma(Hebrew: "שׁוֹשַׁנְתָּא "shoshanta), and usually falls off during the growing process. Anetrogwith an intactpitamis considered especially valuable, but varieties that naturally shed theirpitamduring growth are also considered kosher. When only the stigma breaks off, even post-harvest, the citron can still be considered kosher as long as part of the style has remained attached. If the wholepitam,i.e. the stigma and style, are unnaturally broken off in their entirety, theetrogis not kosher for ritual use.

Pitampreservation technique

[edit]Many morepitamimare preserved today due to anauxindiscovered byEliezer E. Goldschmidt,emeritus professor of horticulture at theHebrew University.While working with thepicloramhormone in a citrus orchard, he unexpectedly discovered that some of theValencia orangesfound nearby had perfectly preservedpitamim.Citrus fruits, other than anetrogor citron hybrid like thebergamot,usually do not preserve theirpitam.On the occasions that they do, theirpitamimtend to be dry, sunken and very fragile. In Goldschmidt's observation, thepitamimwere all fresh and solid like those of theMoroccanor Greek citron varieties.

Experimenting with picloram in a laboratory, Goldschmidt eventually found the correct "dose" to achieve the desired effect: one droplet[clarification needed]of the chemical in three million drops of water.[14][page needed]

Purity

[edit]In order for a citron to be kosher, it must be neithergraftednorhybridizedwith any other species. Only a few traditional varieties are therefore used. To ensure that no grafting is performed, preferred plantations are kept under strict rabbinicalsupervision.

Genetic research

[edit]

The citron varieties traditionally used asetrogare theDiamante citronfrom Italy, theGreek citron,theBalady citronfrom Israel, theMoroccanandYemenite citrons.

A general DNA study was conducted by Eliezer E. Goldschmidt and colleagues which tested and positively identified twelve famousaccessionsof citron for purity and being genetically related.[15]

ThefingeredandFlorentine citrons,although they are also citron varieties or maybehybrids,are not used for the ritual. TheCorsican citronfell into disfavor but has recently been reintroduced for ritual use.

Selection and cultivation

[edit]In addition to the above, there are rabbinical indicators used to distinguish pureetrogimfrom possible hybrids. These traditional indicators have been preserved by continuousselectionperformed by professional farmers.[16]

The most accepted indicators are: 1) a pureetroghas a thick rind, contrasting with its sparing pulpsegmentswhich are also almost dry, 2) the outer surface of anetrogis ribbed and warted, and 3) theetrogpeduncleis somewhat buried inward. By contrast, a lemon or different citron hybrid is missing one or all of the specifications.[17]

A later and not as widely accepted indicator is the orientation of the seed. In a pureetrog,the seeds are oriented vertically, unless crowded by neighboring seeds; in lemons and hybrids, the seeds are oriented horizontally even when they are not crowded.[18]

Theetrogis typically grown from cuttings that are two to four years old. The tree begins to bear fruit about four years after planting the cuttings.[19]If the tree is germinated fromseed,it will not bear fruit for about seven years, and there may be somegenetic changeto the tree or fruit.[20]

Customs

[edit]

To protect theetrogduring the holiday, it is traditionally wrapped in silky flax fibers and stored in a special decorative box, often made from silver.[21]

After the holiday, eating theetrogoretrogjam is considered asegula(efficacious remedy) for a woman to have an easy childbirth.[22]A common Ashkenazi custom is to save theetroguntilTu BiShvatand eat it in candied form or assuccade,while offering prayers that the worshipper merit a beautifuletrognext Sukkot.[23]Some families make jam or liqueur out of theetrogor make apomanderby insertingclovesinto the skin for use asbesamimat thehavdalahceremony afterShabbat.

Etrogimgrown in Israel are not classified as food and are therefore not recommended to be eaten due to the large amount of pesticides used in their agriculture.[24]

Gallery

[edit]-

Rabbi Bergman re-examines an etrog for a student

-

RabbiDov Landauinspecting an etrog

-

Balady citron inBnei Berakmarket

-

Yanova etrog for sale

-

Cross section of Diamante citron, to check for genetic purity

-

Mature fruit of Yanover etrog

-

Cross section of Braverman etrog

-

Cross section in Yemenite citron

-

Cross section of Greek citron

-

Cross section of Balady citron

-

Cross section of a Moroccan citron

-

Yemenite citron (left) and a Balady citron (right)

-

Cross section ofvariety etrogcitron, and in fingered citron.

-

Diamante citron withoutpitam

-

Diamante citron withpitam

-

Inspecting an etrog for flaws

-

Inspecting a Yemenite citron

-

Shmita inKefar Chabad,orchard left untended

-

Young plants in Kefar Chabad

-

Yemenite citron on tree

-

Etrog covered with cloves

-

Four speciesmarket in Tel Aviv

-

Pitamclose-up

-

Etrog blossom

-

Etrog tree fromJewish Encyclopedia

-

Man inMea Sheariminspecting etrog

-

Moroccan etrog with prominentgartel

-

German painting

-

Two Hasidim inBnei Berak

-

Old photo of grower

-

An etrog from many angles

-

Round silver etrog box

-

Etrog with half-driedpitam

-

Etrog plants in nursery

-

Etrog leaves

-

Citron (etrog) flowers

-

Silver etrog box designed by Rabbi Chaim-Joseph-Meyer Elefant (1897-1976) in the early 1950s

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"In Calabria, rabbis and farmers continue a 2,000-year-old etrog tradition | the Times of Israel".The Times of Israel.

- ^The Citrus IndustryArchivedMarch 8, 2008, at theWayback Machine

- ^Moster (2018),p. 24.

- ^"Jerusalem Dig Uncovers Earliest Evidence of Local Cultivation of Etrogs".Haaretz.Retrieved2022-10-10.

- ^Stetkevych, Suzanne Pinckney (1994).Reorientations: Arabic and Persian poetry.Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 131–3.ISBN0-253-35493-5.

- ^Hadith no. 288,Book 6 of theSahih Muslim- via Sunnah

- ^Moster (2018),p. 25.

- ^Nahon, Peter (2015-06-01)."Les Agrumes d'Intérieur: des variétés historiques aux essais actuels".Fruits Oubliés.

- ^"ethrog".citrusvariety.ucr.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-06-08.Retrieved2008-04-15.

- ^Fuller, Dorian Q.; Castillo, Cristina; Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor; Qin, Ling; Weisskopf, Alison (15 January 2018).Charred pummelo peel, historical linguistics and other tree crops: Approaches to framing the historical context of early Citrus cultivation in East, South and Southeast Asia.Collection du Centre Jean Bérard. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard.ISBN9782918887775.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^First evidence of the etrog tree in Israel

- ^"America's Only Etrog Farmer Isn't Even Jewish".Tablet Magazine.2011-10-12.Retrieved2022-10-10.

- ^Wall, Alix (2016-10-14)."The elegant, elusive etrog: Growing the symbol of Sukkot in California".J.Retrieved2022-10-10.

- ^Goldschmidt, E. E.; Leshem, B. (1971)."Style Abscission in the Citron (Citrus medica L.) and Other Citrus Species: Morphology, Physiology, and Chemical Control with Picloram".American Journal of Botany.58(1): 14–23.doi:10.2307/2441301.JSTOR2441301– via JSTOR.

- ^Search Authentic CitronArchived2019-01-26 at theWayback Machine

- A brief documentation of this study could be found at theGlobal Citrus Germplasm NetworkArchived2008-04-10 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Article by Professor Goldschmidt, published byTehumin,summer 5741 (1981), booklet 2, p. 144

- ^Letter by RabbiShmuel Yehuda KatzenellenbogenofPaduafrom the mid-16th century, printed inTeshuvat ha'Remochapter 126.

- ^Shiurey Kneseth Hagdola and Olat Shabbat, cited byMagen Avraham,Orach Chaimchapter 648, comment 23

- ^Chiri, Alfredo. (2002).EtrogArchivedApril 4, 2005, at theWayback Machine

- ^"Sunkist Website".Archived fromthe originalon October 17, 2007.

- ^"The Saga of the Citron".Reform Judaism.

- ^Weisberg, Chana (2004).Expecting Miracles: Finding meaning and spirituality in pregnancy through Judaism.Urim Publications. p. 134.ISBN9657108519.

- ^"Redirecting..."aish.Archived fromthe originalon 2020-03-01.Retrieved2008-01-31.

{{cite web}}:Cite uses generic title (help) - ^"זהירות: למרות הסגולות מסוכן לאכול ריבת אתרוגים".סרוגים(in Hebrew). 2011-10-24.Retrieved2020-09-29.

- Moster, David Z. (2018).Etrog: How a Chinese Fruit Became a Jewish Symbol.Palgrave Macmillan.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73736-2.ISBN978-3-319-73735-5.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit] Media related toEtrogat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toEtrogat Wikimedia Commons- The Citrus Variety CollectionArchived2015-06-08 at theWayback Machineby theUniversity of CaliforniaRiverside

- Ancient Treasures and the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Mosaic depicting anetrog

- Lulav, Etrog, Shofar and Menorah, 2nd Cent. CE, Ostia Synagogue

- An antique Hebrew coin depicting anetrog

- Pictureshomecitrusgrowers.co.uk

- Evyatar Marienberg and David Carpenter,The Stealing of the "Apple of Eve" from the 13th century Synagogue of Winchester[permanent dead link],Henri III Fine Rolls Project, Fine of the Month:December 2011

- A Huge Etrog-looking Citron in Geetha's Kitchen, amazing photos

- Know Your Etrog,website with educational pictures, information how to plant your own tree.

- The Symbolism of the Lulav and Esrog,various sources explaining the symbolism and meaning of the etrog.