Eusebian Canons

Eusebian canons,Eusebian sectionsorEusebian apparatus,[1]also known asAmmonian sections,are the system of dividing the fourGospelsused betweenlate Antiquityand theMiddle Ages.The divisions intochapters and versesused in modern texts date only from the 13th and 16th centuries, respectively. The sections are indicated in the margin of nearly all Greek and Latinmanuscriptsof theBible,but can be also found in periphical Bible transmissions as Syriac and Christian Palestinian Aramaic (Codex Sinaiticus Rescriptus) 5th to 8th century,[2][3]and in Ethiopian manuscripts until the 14th and 15th centuries, with a few produced as late as the 17th century.[4]These are usually summarized incanon tablesat the start of the Gospels. There are about 1165 sections: 355 forMatthew,235 forMark,343 forLuke,and 232 forJohn;the numbers, however, vary slightly in different manuscripts.[5]

The canon tables were made to create a sense of divinity within the reader’s soul, to understand and reflect upon the various colors and patterns to achieve a higher connection with God.[6]

Authorship

[edit]Until the 19th century it was mostly believed that these divisions were devised byAmmonius of Alexandria,at the beginning of the 3rd century (c.220), in connection with aHarmony of the Gospels,now lost, which he composed. It was traditionally believed that he divided the four Gospels into small numbered sections, which were similar in content where the narratives are parallel. He then wrote the sections of the three last Gospels, or simply the section numbers with the name of the respectiveevangelist,in parallel columns opposite the corresponding sections of the Gospel of Matthew, which he had chosen as the basis of hisgospel harmony.It is now believed that the work of Ammonius was restricted to whatEusebius of Caesarea(265-340) states concerning it in hisletter to Carpianus,namely, that he placed the parallel passages of the last three Gospels alongside the text of Matthew, and the sections traditionally credited to Ammonius are now ascribed to Eusebius, who was always credited with the final form of the tables.[7]

The Eusebian Tables

[edit]

The harmony of Ammonius suggested to Eusebius, as he says in his letter, the idea of drawing up ten tables (kanones) in which the sections in question were so classified as to show at a glance where each Gospel agreed with or differed from the others. In the first nine tables he placed in parallel columns the numbers of the sections common to the four, or three, or two, evangelists; namely: (1) Matt., Mark, Luke, John; (2) Matt., Mark, Luke; (3) Matt., Luke, John; (4) Matt., Mark, John; (5) Matt., Luke; (6) Matt., Mark; (7) Matt., John; (8) Luke, Mark; (9) Luke, John. In the tenth he noted successively the sections special to each evangelist. Sections "Mark, Luke, John" and "Mark, John" are absent because no text is common to Mark and John without a parallel in at least Matthew.

| Table # | Matthew | Mark | Luke | John |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Quo Quattor | ||||

| Canon I. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| In Quo Tres | ||||

| Canon II. | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Canon III. | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Canon IV. | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| In Quo Duo | ||||

| Canon V. | Yes | Yes | ||

| Canon VI. | Yes | Yes | ||

| Canon VII. | Yes | Yes | ||

| Canon VIII. | Yes | Yes | ||

| Canon IX. | Yes | Yes | ||

| In Quo Matth. Proprie | ||||

| Canon X | Yes | |||

| In Quo Marc. Proprie | ||||

| Canon X | Yes | |||

| In Quo Luc. Proprie | ||||

| Canon X | Yes | |||

| In Quo Ioh. Proprie | ||||

| Canon X | Yes | |||

The usefulness of these tables for the purpose of reference and comparison soon brought them into common use, and from the 5th century the Ammonian sections, with references to the Eusebian tables, were indicated in the margin of the manuscripts. Opposite each section was written its number, and underneath this the number of the Eusebian table to be consulted in order to find the parallel texts or text; a reference to the tenth table would show that this section was proper to that evangelist. These marginal notes are reproduced in several editions ofTischendorf's New Testament.

Eusebius's explanatoryletter to Carpianuswas also very often reproduced before the tables.

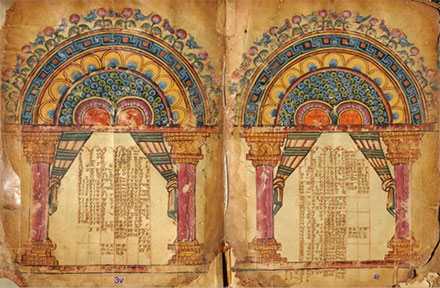

Illuminated canon tables

[edit]The tables themselves were usually placed at the start of aGospel Book;inilluminatedworks they were placed in round-headed arcade-like frames, of which the general form remained remarkably consistent through to theRomanesqueperiod. This form was derived fromLate Antiquebook-painting frames like those in theChronography of 354.In many examples the tables are the only decoration in the whole book, perhaps other than some initials. In particular, canon tables, withEvangelist portraits,are very important for the study of the development of manuscript painting in the earliest part of theEarly Medievalperiod, where very few manuscripts survive, and even the most decorated of those have fewer pages illuminated than was the case later.

Images

[edit]-

Eusebian tables before text of the Gospels inCodex Harleianus 5567(Gregory-Aland 116; 12th century)

-

One of the canon tables from the 8th centuryCodex Beneventanus.

-

TheLondon Canon Tablesare two folios from a Byzantine manuscript of the 6th or 7th century, showing the typical arcaded frame.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^D. C. Parker,An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and their Texts,Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 24.

- ^Sebastian P. Brock, 'Review of Alain Desreumaux,Codex sinaiticus Zosimi rescriptus(Histoire du Texte Biblique, 3),The Journal of Theological Studies,NEW SERIES,50 (1999), p. 766.

- ^Christa Müller-Kessler and Michael Sokoloff,The Christian Palestinian Aramaic New Testament Version from the Early Period. Gospels(A Corpus of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, IIA; STYX: Groningen, 1998), pp. 94–95, 97, 139–140, 168–169.

- ^Carla Zanotti-Eman, "Linear Decoration in Ethiopian Manuscripts", inAfrican Zion,ed. Roderick Grierson (New Haven: Yale University, 1993), p. 66.ISBN0-300-05819-5

- ^Bruce M. Metzger,Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography,Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 42.ISBN978-0-19-502924-6

- ^Nersessian, Vrej (2001).The Bible in the Armenian Tradition.London: The British Library. pp. 70&74.ISBN0-89236-640-0.

- ^Martin Wallraff,Die Kanontafeln des Euseb von Kaisareia(Manuscripta Biblica Paratextus Biblici, 1) Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2021.ISBN978-3-11-043952-6

References

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ammonian Sections".Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ammonian Sections".Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.