Fairy tale

Afairy tale(alternative names includefairytale,fairy story,household tale,[1]magic tale,orwonder tale) is ashort storythat belongs to thefolklore genre.[2]Such stories typically featuremagic,enchantments,andmythicalor fanciful beings. In most cultures, there is no clear line separating myth from folk or fairy tale; all these together form the literature of preliterate societies.[3]Fairy tales may be distinguished from other folk narratives such aslegends(which generally involve belief in the veracity of the events described)[4]and explicit moral tales, including beastfables.Prevalent elements includedragons,dwarfs,elves,fairies,giants,gnomes,goblins,griffins,merfolk,monsters,monarchy,pixies,talking animals,trolls,unicorns,witches,wizards,magic,andenchantments.

In less technical contexts, the term is also used to describe something blessed with unusual happiness, as in "fairy-tale ending" (ahappy ending)[5]or "fairy-taleromance".Colloquially, the term" fairy tale "or" fairy story "can also mean any far-fetched story ortall tale;it is used especially of any story that not only is not true, but could not possibly be true. Legends are perceived as real within their culture; fairy tales may merge into legends, where the narrative is perceived both by teller and hearers as being grounded in historical truth. However, unlike legends andepics,fairy tales usually do not contain more than superficial references to religion and to actual places, people, and events; they take place "once upon a time"rather than in actual times.[6]

Fairy tales occur both in oral and in literary form (literary fairy tale); the name "fairy tale" ( "conte de fées"in French) was first ascribed to them byMadame d'Aulnoyin the late 17th century. Many of today's fairy tales have evolved from centuries-old stories that have appeared, with variations, in multiple cultures around the world.[7]

The history of the fairy tale is particularly difficult to trace because only the literary forms can survive. Still, according to researchers at universities inDurhamandLisbon,such stories may date back thousands of years, some to theBronze Age.[8][9]Fairy tales, and works derived from fairy tales, are still written today.

TheJatakasare probably the oldest collection of such tales in literature, and the greater part of the rest are demonstrably more than a thousand years old. It is certain that much (perhaps one-fifth) of the popular literature of modern Europe is derived from those portions of this large bulk which came west with theCrusadesthrough the medium of Arabs and Jews.[10]

Folklorists have classified fairy tales in various ways. TheAarne–Thompson–Uther Indexand the morphological analysis ofVladimir Proppare among the most notable. Other folklorists have interpreted the tales' significance, but no school has been definitively established for the meaning of the tales.

Terminology

[edit]Somefolkloristsprefer to use the German termMärchenor "wonder tale"[11]to refer to the genre rather thanfairy tale,a practice given weight by the definition of Thompson in his 1977 [1946] edition ofThe Folktale:

"...a tale of some length involving a succession ofmotifsor episodes. It moves in an unreal world without definite locality or definite creatures and is filled with the marvellous. In this never-never land, humbleheroeskill adversaries, succeed to kingdoms and marry princesses. "[12]

The characters and motifs of fairy tales are simple and archetypal:princessesandgoose-girls;youngest sonsand gallantprinces;ogres,giants,dragons,andtrolls;wicked stepmothersandfalse heroes;fairy godmothersand othermagical helpers,oftentalking horses, or foxes, or birds;glass mountains; and prohibitions and breaking of prohibitions.[13]

Definition

[edit]

Although the fairy tale is a distinct genre within the larger category of folktale, the definition that marks a work as a fairy tale is a source of considerable dispute.[14]The term itself comes from the translation of Madame D'Aulnoy'sConte de fées,first used in her collection in 1697.[15]Common parlance conflates fairy tales withbeast fablesand other folktales, and scholars differ on the degree to which the presence of fairies and/or similarly mythical beings (e.g.,elves,goblins,trolls,giants, huge monsters, or mermaids) should be taken as a differentiator.Vladimir Propp,in hisMorphology of the Folktale,criticized the common distinction between "fairy tales" and "animal tales" on the grounds that many tales contained bothfantasticelements and animals.[16]Nevertheless, to select works for his analysis, Propp used allRussian folktalesclassified as a folklore,Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index300–749,—in a cataloguing system that made such a distinction—to gain a clear set of tales.[17]His own analysis identified fairy tales by their plot elements, but that in itself has been criticized, as the analysis does not lend itself easily to tales that do not involve aquest,and furthermore, the same plot elements are found in non-fairy tale works.[18]

Were I asked, what is a fairytale? I should reply, ReadUndine:that is a fairytale... of all fairytales I know, I think Undine the most beautiful.

— George MacDonald,The Fantastic Imagination

AsStith Thompsonpoints out, talking animals and the presence ofmagicseem to be more common to the fairy tale thanfairiesthemselves.[19]However, the mere presence of animals that talk does not make a tale a fairy tale, especially when the animal is clearly a mask on a human face, as infables.[20]

In his essay "On Fairy-Stories",J.R.R.Tolkienagreed with the exclusion of "fairies" from the definition, defining fairy tales as stories about the adventures of men inFaërie,the land of fairies, fairytale princes and princesses,dwarves,elves, and not only other magical species but many other marvels.[21]However, the same essay excludes tales that are often considered fairy tales, citing as an exampleThe Monkey's Heart,whichAndrew Langincluded inThe Lilac Fairy Book.[20]

Steven Swann Jones identified the presence of magic as the feature by which fairy tales can be distinguished from other sorts of folktales.[22]Davidson and Chaudri identify "transformation" as the key feature of the genre.[11]From a psychological point of view, Jean Chiriac argued for the necessity of thefantasticin these narratives.[23]

In terms of aesthetic values,Italo Calvinocited the fairy tale as a prime example of "quickness" in literature, because of the economy and concision of the tales.[24]

History of the genre

[edit]

Originally, stories that would contemporarily be considered fairy tales were not marked out as a separate genre. The German term "Märchen"stems from the old German word"Mär",which means news or tale.[25]The word "Märchen"is thediminutiveof the word "Mär",therefore it means a" little story ". Together with the common beginning"once upon a time",this tells us that a fairy tale or a märchen was originally a little story from a long time ago when the world was still magic. (Indeed, one less regular Germanopeningis "In the old times when wishing was still effective".)[26]

The French writers and adaptors of thecontede féesgenre often included fairies in their stories; the genre name became "fairy tale" in English translation and "gradually eclipsed the more general termfolktale that covered a wide variety of oral tales ".[27]Jack Zipes also attributes this shift to changing sociopolitical conditions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that led to the trivialization of these stories by the upper classes.[27]

Roots of the genre come from different oral stories passed down in European cultures. The genre was first marked out by writers of theRenaissance,such asGiovanni Francesco StraparolaandGiambattista Basile,and stabilized through the works of later collectors such asCharles Perraultand theBrothers Grimm.[28]In this evolution, the name was coined when theprécieusestook up writing literary stories;Madame d'Aulnoyinvented the termConte de fée,or fairy tale, in the late 17th century.[29]

Before the definition of the genre of fantasy, many works that would now be classified as fantasy were termed "fairy tales", including Tolkien'sThe Hobbit,George Orwell'sAnimal Farm,andL. Frank Baum'sThe Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[30]Indeed, Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories" includes discussions ofworld-buildingand is considered a vital part of fantasy criticism. Although fantasy, particularly the subgenre offairytale fantasy,draws heavily on fairy tale motifs,[31]the genres are now regarded as distinct.

Folk and literary

[edit]The fairy tale, told orally, is a sub-class of thefolktale.Many writers have written in the form of the fairy tale. These are the literary fairy tales, orKunstmärchen.[15]The oldest forms, fromPanchatantrato thePentamerone,show considerable reworking from the oral form.[32]TheGrimm brotherswere among the first to try to preserve the features of oral tales. Yet the stories printed under the Grimm name have been considerably reworked to fit the written form.[33]

Literary fairy tales and oral fairy tales freely exchanged plots, motifs, and elements with one another and with the tales of foreign lands.[34]The literary fairy tale came into fashion during the 17th century, developed by aristocratic women as a parlour game. This, in turn, helped to maintain the oral tradition. According toJack Zipes,"The subject matter of the conversations consisted of literature, mores, taste, and etiquette, whereby the speakers all endeavoured to portray ideal situations in the most effective oratorical style that would gradually have a major effect on literary forms."[35]Many 18th-century folklorists attempted to recover the "pure" folktale, uncontaminated by literary versions. Yet while oral fairy tales likely existed for thousands of years before the literary forms, there is no pure folktale, and each literary fairy tale draws on folk traditions, if only in parody.[36]This makes it impossible to trace forms of transmission of a fairy tale. Oral story-tellers have been known to read literary fairy tales to increase their own stock of stories and treatments.[37]

History

[edit]

Theoral traditionof the fairy tale came long before the written page. Tales were told or enacted dramatically, rather than written down, and handed down from generation to generation. Because of this, the history of their development is necessarily obscure and blurred. Fairy tales appear, now and again, in written literature throughout literate cultures,[a][b]as inThe Golden Ass,which includesCupid and Psyche(Roman,100–200 AD),[42]or thePanchatantra(India3rd century BC),[42]but it is unknown to what extent these reflect the actual folk tales even of their own time. The stylistic evidence indicates that these, and many later collections, reworked folk tales into literary forms.[32]What they do show is that the fairy tale has ancient roots, older than theArabian Nightscollection of magical tales (compiledcirca1500 AD),[42]such asVikram and the Vampire,andBel and the Dragon.Besides such collections and individual tales, inChinaTaoistphilosophers such asLieziandZhuangzirecounted fairy tales in their philosophical works.[43]In the broader definition of the genre, the first famous Western fairy tales are those ofAesop(6th century BC) inancient Greece.

Scholarship points out thatMedieval literaturecontains early versions or predecessors of later known tales and motifs, such asthe grateful dead,The Bird Loveror the quest for the lost wife.[44][c]Recognizable folktales have also been reworked as the plot of folk literature and oral epics.[47]

Jack Zipes writes inWhen Dreams Came True,"There are fairy tale elements inChaucer'sThe Canterbury Tales,Edmund Spenser'sThe Faerie Queene,and in many ofWilliam Shakespeareplays. "[48]King Learcan be considered a literary variant of fairy tales such asWater and SaltandCap O' Rushes.[49]The tale itself resurfaced inWestern literaturein the 16th and 17th centuries, withThe Facetious Nights of StraparolabyGiovanni Francesco Straparola(Italy, 1550 and 1553),[42]which contains many fairy tales in its inset tales, and theNeapolitantales ofGiambattista Basile(Naples, 1634–36),[42]which are all fairy tales.[50]Carlo Gozzimade use of many fairy tale motifs among hisCommedia dell'Artescenarios,[51]including among them one based onThe Love For Three Oranges(1761).[52]Simultaneously,Pu Songling,in China, included many fairy tales in his collection,Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio(published posthumously, 1766),[43]which has been described by Yuken Fujita ofKeio Universityas having "a reputation as the most outstanding short story collection."[53]The fairy tale itself became popular among theprécieusesof upper-classFrance(1690–1710),[42]and among the tales told in that time were the ones ofLa Fontaineand theContesofCharles Perrault(1697), who fixed the forms ofSleeping BeautyandCinderella.[54]Although Straparola's, Basile's and Perrault's collections contain the oldest known forms of various fairy tales, on the stylistic evidence, all the writers rewrote the tales for literary effect.[55]

The Salon Era

[edit]In the mid-17th century, a vogue for magical tales emerged among the intellectuals who frequented thesalonsof Paris. These salons were regular gatherings hosted by prominent aristocratic women, where women and men could gather together to discuss the issues of the day.

In the 1630s, aristocratic women began to gather in their own living rooms, salons, to discuss the topics of their choice: arts and letters, politics, and social matters of immediate concern to the women of their class: marriage, love, financial and physical independence, and access to education. This was a time when women were barred from receiving a formal education. Some of the most gifted women writers of the period came out of these early salons (such asMadeleine de ScudéryandMadame de Lafayette), which encouraged women's independence and pushed against the gender barriers that defined their lives. Thesalonnièresargued particularly for love and intellectual compatibility between the sexes, opposing the system of arranged marriages.

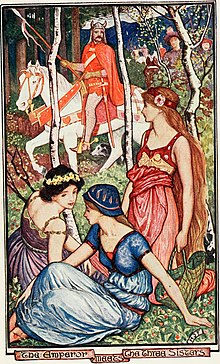

Sometime in the middle of the 17th century, a passion for the conversationalparlour gamebased on the plots of oldfolk talesswept through the salons. Eachsalonnièrewas called upon to retell an old tale or rework an old theme, spinning clever new stories that not only showcased verbal agility and imagination but also slyly commented on the conditions of aristocratic life. Great emphasis was placed on a mode of delivery that seemed natural and spontaneous. The decorative language of the fairy tales served an important function: disguising the rebellious subtext of the stories and sliding them past the court censors. Critiques of court life (and even of the king) were embedded in extravagant tales and in dark, sharplydystopianones. Not surprisingly, the tales by women often featured young (but clever) aristocratic girls whose lives were controlled by the arbitrary whims of fathers, kings, and elderly wicked fairies, as well as tales in which groups of wise fairies (i.e., intelligent, independent women) stepped in and put all to rights.

Thesalontales as they were originally written and published have been preserved in a monumental work calledLe Cabinet des Fées,an enormous collection of stories from the 17th and 18th centuries.[15]

Later works

[edit]

The first collectors to attempt to preserve not only the plot and characters of the tale, but also the style in which they were told, was theBrothers Grimm,collecting German fairy tales; ironically, this meant although their first edition (1812 & 1815)[42]remains a treasure for folklorists, they rewrote the tales in later editions to make them more acceptable, which ensured their sales and the later popularity of their work.[56]

Such literary forms did not merely draw from the folktale, but also influenced folktales in turn. The Brothers Grimm rejected several tales for their collection, though told orally to them by Germans, because the tales derived from Perrault, and they concluded they were therebyFrenchand not German tales; an oral version of "Bluebeard"was thus rejected, and the tale ofLittle Briar Rose,clearly related to Perrault's "Sleeping Beauty",was included only because Jacob Grimm convinced his brother that the figure ofBrynhildr,from much earlierNorse mythology,proved that the sleeping princess was authenticallyGermanicfolklore.[57]

This consideration of whether to keepSleeping Beautyreflected a belief common among folklorists of the 19th century: that the folk tradition preserved fairy tales in forms from pre-history except when "contaminated" by such literary forms, leading people to tell inauthentic tales.[58]The rural, illiterate, and uneducated peasants, if suitably isolated, were thefolkand would tell purefolktales.[59]Sometimes they regarded fairy tales as a form of fossil, the remnants of a once-perfect tale.[60]However, further research has concluded that fairy tales never had a fixed form, and regardless of literary influence, the tellers constantly altered them for their own purposes.[61]

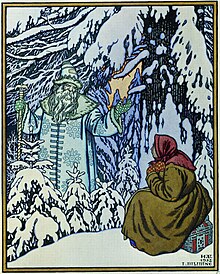

The work of the Brothers Grimm influenced other collectors, both inspiring them to collect tales and leading them to similarly believe, in a spirit ofromantic nationalism,that the fairy tales of a country were particularly representative of it, to the neglect of cross-cultural influence. Among those influenced were the RussianAlexander Afanasyev(first published in 1866),[42]the NorwegiansPeter Christen AsbjørnsenandJørgen Moe(first published in 1845),[42]the RomanianPetre Ispirescu(first published in 1874), the EnglishJoseph Jacobs(first published in 1890),[42]andJeremiah Curtin,an American who collected Irish tales (first published in 1890).[36]Ethnographers collected fairy tales throughout the world, finding similar tales in Africa, the Americas, and Australia;Andrew Langwas able to draw on not only the written tales of Europe and Asia, but those collected by ethnographers, to fill his"coloured" fairy books series.[62]They also encouraged other collectors of fairy tales, as whenYei Theodora Ozakicreated a collection,Japanese Fairy Tales(1908), after encouragement from Lang.[63]Simultaneously, writers such asHans Christian AndersenandGeorge MacDonaldcontinued the tradition of literary fairy tales. Andersen's work sometimes drew on old folktales, but more often deployed fairytale motifs and plots in new tales.[64]MacDonald incorporated fairytale motifs both in new literary fairy tales, such asThe Light Princess,and in works of the genre that would become fantasy, as inThe Princess and the GoblinorLilith.[65]

Cross-cultural transmission

[edit]Two theories of origins have attempted to explain the common elements in fairy tales found spread over continents. One is that a single point of origin generated any given tale, which then spread over the centuries; the other is that such fairy tales stem from common human experience and therefore can appear separately in many different origins.[66]

Fairy tales with very similar plots, characters, and motifs are found spread across many different cultures. Many researchers hold this to be caused by the spread of such tales, as people repeat tales they have heard in foreign lands, although the oral nature makes it impossible to trace the route except by inference.[67]Folklorists have attempted to determine the origin by internal evidence, which can not always be clear;Joseph Jacobs,comparing theScottishtaleThe Ridere of Riddleswith the version collected by the Brothers Grimm,The Riddle,noted that inThe Ridere of Riddlesone hero ends uppolygamouslymarried, which might point to an ancient custom, but inThe Riddle,the simpler riddle might argue greater antiquity.[68]

Folklorists of the "Finnish" (or historical-geographical) school attempted to place fairy tales to their origin, with inconclusive results.[69]Sometimes influence, especially within a limited area and time, is clearer, as when considering the influence of Perrault's tales on those collected by the Brothers Grimm.Little Briar-Roseappears to stem from Perrault'sTheSleeping Beauty,as the Grimms' tale appears to be the only independent German variant.[70]Similarly, the close agreement between the opening of the Grimms' version ofLittle Red Riding Hoodand Perrault's tale points to an influence, although the Grimms' version adds a different ending (perhaps derived fromThe Wolf and the Seven Young Kids).[71]

Fairy tales tend to take on the color of their location, through the choice of motifs, the style in which they are told, and the depiction of character and local color.[72]

The Brothers Grimm believed that European fairy tales derived from the cultural history shared by allIndo-Europeanpeoples and were therefore ancient, far older than written records. This view is supported by research by theanthropologistJamie Tehrani and the folklorist Sara Graca Da Silva usingphylogenetic analysis,a technique developed byevolutionary biologiststo trace the relatedness of living and fossilspecies.Among the tales analysed wereJack and the Beanstalk,traced to the time of splitting of Eastern and Western Indo-European, over 5000 years ago. BothBeauty and the BeastandRumpelstiltskinappear to have been created some 4000 years ago. The story ofThe Smith and the Devil(Deal with the Devil) appears to date from theBronze Age,some 6000 years ago.[8]Various other studies converge to suggest that some fairy tales, for example theswan maiden,[73][74][75]could go back to the Upper Palaeolithic.

Association with children

[edit]

Originally, adults were the audience of a fairy tale just as often as children.[76]Literary fairy tales appeared in works intended for adults, but in the 19th and 20th centuries the fairy tale became associated with children's literature.

Theprécieuses,includingMadame d'Aulnoy,intended their works for adults, but regarded their source as the tales that servants, or other women of lower class, would tell to children.[77]Indeed, a novel of that time, depicting a countess's suitor offering to tell such a tale, has the countess exclaim that she loves fairy tales as if she were still a child.[77]Among the lateprécieuses,Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumontredacted a version ofBeauty and the Beastfor children, and it is her tale that is best known today.[78]The Brothers Grimm titled their collectionChildren's and Household Talesand rewrote their tales after complaints that they were not suitable for children.[79]

In the modern era, fairy tales were altered so that they could be read to children. The Brothers Grimm concentrated mostly on sexual references;[80]Rapunzel,in the first edition, revealed the prince's visits by asking why her clothing had grown tight, thus letting the witch deduce that she was pregnant, but in subsequent editions carelessly revealed that it was easier to pull up the prince than the witch.[81]On the other hand, in many respects, violence—particularly when punishing villains—was increased.[82]Other, later, revisions cut out violence; J.R.R.Tolkien noted thatThe Juniper Treeoften had itscannibalisticstew cut out in a version intended for children.[83]The moralizing strain in theVictorian eraaltered the classical tales to teach lessons, as whenGeorge CruikshankrewroteCinderellain 1854 to containtemperancethemes. His acquaintanceCharles Dickensprotested, "In an utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that fairy tales should be respected."[84][85]

Psychoanalystssuch asBruno Bettelheim,who regarded the cruelty of older fairy tales as indicative of psychological conflicts, strongly criticized this expurgation, because it weakened their usefulness to both children and adults as ways of symbolically resolving issues.[86]Fairy tales do teach children how to deal with difficult times. To quote Rebecca Walters (2017, p. 56) "Fairytales and folktales are part of the cultural conserve that can be used to address children's fears…. and give them some role training in an approach that honors the children's window of tolerance ". These fairy tales teach children how to deal with certain social situations and helps them to find their place in society.[87]Fairy tales teach children other important lessons too. For example, Tsitsani et al. carried out a study on children to determine the benefits of fairy tales. Parents of the children who took part in the study found that fairy tales, especially the color in them, triggered their child's imagination as they read them.[88]JungianAnalyst and fairy tale scholarMarie Louise Von Franzinterprets fairy tales[d]based on Jung's view of fairy tales as a spontaneous and naive product of soul, which can only express what soul is.[89]That means, she looks at fairy tales as images of different phases of experiencing the reality of the soul. They are the "purest and simplest expression ofcollective unconsciouspsychic processes "and" they represent the archetypes in their simplest, barest and most concise form "because they are less overlaid with conscious material than myths and legends." In this pure form, the archetypal images afford us the best clues to the understanding of the processes going on in the collective psyche "." The fairy tale itself is its own best explanation; that is, its meaning is contained in the totality of its motifs connected by the thread of the story. [...] Every fairy tale is a relatively closed system compounding one essential psychological meaning which is expressed in a series of symbolical pictures and events and is discoverable in these "." I have come to the conclusion that all fairy tales endeavour to describe one and the same psychic fact, but a fact so complex and far-reaching and so difficult for us to realize in all its different aspects that hundreds of tales and thousands of repetitions with a musician's variation are needed until this unknown fact is delivered into consciousness; and even then the theme is not exhausted. This unknown fact is what Jung calls the Self, which is the psychic reality of the collective unconscious. [...] Every archetype is in its essence only one aspect of the collective unconscious as well as always representing also the whole collective unconscious.[90]

Other famous people commented on the importance of fairy tales, especially for children. For example,G. K. Chestertonargued that"Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon."[91]Albert Einstein once showed how important he believed fairy tales were for children's intelligence in the quote "If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairytales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairytales."[92]

The adaptation of fairy tales for children continues.Walt Disney's influentialSnow White and the Seven Dwarfswas largely (although certainly not solely) intended for the children's market.[93]TheanimeMagical Princess Minky Momodraws on the fairy taleMomotarō.[94]Jack Zipes has spent many years working to make the oldertraditional storiesaccessible to modern readers and their children.[95]

Motherhood

[edit]Many fairy tales feature an absentee mother, as an example "Beauty and the Beast","The Little Mermaid","Little Red Riding Hood"and"Donkeyskin",where the mother is deceased or absent and unable to help the heroines. Mothers are depicted as absent or wicked in the most popular contemporary versions of tales like"Rapunzel","Snow White","Cinderella"and"Hansel and Gretel",however, some lesser known tales or variants such as those found in volumes edited byAngela CarterandJane Yolendepict mothers in a more positive light.[96]

Carter's protagonist inThe Bloody Chamberis an impoverished piano student married to aMarquiswho was much older than herself to "banish the spectre of poverty". The story is a variant onBluebeard,a tale about a wealthy man who murders numerous young women. Carter's protagonist, who is unnamed, describes her mother as "eagle-featured" and "indomitable". Her mother is depicted as a woman who is prepared for violence, instead of hiding from it or sacrificing herself to it. The protagonist recalls how her mother kept an "antique service revolver" and once "shot a man-eating tiger with her own hand."[96]

Contemporary tales

[edit]Literary

[edit]

Incontemporary literature,many authors have used the form of fairy tales for various reasons, such as examining thehuman conditionfrom the simple framework a fairytale provides.[97]Some authors seek to recreate a sense of the fantastic in a contemporary discourse.[98]Some writers use fairy tale forms for modern issues;[99]this can include using the psychological dramas implicit in the story, as whenRobin McKinleyretoldDonkeyskinas the novelDeerskin,with emphasis on the abusive treatment the father of the tale dealt to his daughter.[100]Sometimes, especially in children's literature, fairy tales are retold with a twist simply for comic effect, such asThe Stinky Cheese ManbyJon ScieszkaandThe ASBO Fairy Talesby Chris Pilbeam. A common comic motif is a world where all the fairy tales take place, and the characters are aware of their role in the story,[101]such as in the film seriesShrek.

Other authors may have specific motives, such as multicultural orfeministreevaluations of predominantlyEurocentricmasculine-dominated fairy tales, implying critique of older narratives.[102]The figure of thedamsel in distresshas been particularly attacked by many feminist critics. Examples of narrative reversal rejecting this figure includeThe Paperbag PrincessbyRobert Munsch,a picture book aimed at children in which a princess rescues a prince,Angela Carter'sThe Bloody Chamber,which retells a number of fairy tales from a female point of view and Simon Hood's contemporary interpretation of various popular classics.[citation needed]

There are also many contemporary erotic retellings of fairy tales, which explicitly draw upon the original spirit of the tales, and are specifically for adults. Modern retellings focus on exploring the tale through use of the erotic, explicit sexuality, dark and/or comic themes, female empowerment,fetishandBDSM,multicultural, and heterosexual characters.Cleis Presshas released several fairy tale-themed erotic anthologies, includingFairy Tale Lust,Lustfully Ever After,andA Princess Bound.

It may be hard to lay down the rule between fairy tales andfantasiesthat use fairy tale motifs, or even whole plots, but the distinction is commonly made, even within the works of a single author: George MacDonald'sLilithandPhantastesare regarded as fantasies, while his "The Light Princess","The Golden Key",and" The Wise Woman "are commonly called fairy tales. The most notable distinction is that fairytale fantasies, like other fantasies, make use of novelistic writing conventions of prose, characterization, or setting.[103]

Film

[edit]Fairy tales have been enacted dramatically; records exist of this incommedia dell'arte,[104]and later inpantomime.[105]Unlike oral and literacy form, fairy tales in film is considered one of the most effective way to convey the story to the audience. The advent of cinema has meant that such stories could be presented in a more plausible manner, with the use of special effects and animation.The Walt Disney Companyhas had a significant impact on the evolution of the fairy tale film. Some of the earliest short silent films from the Disney studio were based on fairy tales, and some fairy tales were adapted into shorts in the musical comedy series "Silly Symphony",such asThree Little Pigs.Walt Disney's first feature-length filmSnow White and the Seven Dwarfs,released in 1937, was a ground-breaking film for fairy tales and, indeed, fantasy in general.[93]With the cost of over 400 percent of the budget and more than 300 artists, assistants and animators,Snow White and the Seven Dwarfswas arguably one of the highest work force demanded film at that time.[106]The studio even hiredDon Grahamto open animation training programs for more than 700 staffs.[107]As for the motion capture and personality expression, the studio used a dancer,Marjorie Celeste,from the beginning to the end for the best results.[107]Disney and his creative successors have returned to traditional and literary fairy tales numerous times with films such asCinderella(1950),Sleeping Beauty(1959),The Little Mermaid(1989) andBeauty and the Beast(1991). Disney's influence helped establish the fairy tale genre as a genre for children, and has been accused by some ofbowdlerizingthe gritty naturalism – and sometimes unhappy endings – of many folk fairy tales.[100]However, others note that the softening of fairy tales occurred long before Disney, some of which was even done by the Grimm brothers themselves.[108][109]

Many filmed fairy tales have been made primarily for children, from Disney's later works to Aleksandr Rou's retelling ofVasilissa the Beautiful,the firstSoviet filmto use Russian folk tales in a big-budget feature.[110]Others have used the conventions of fairy tales to create new stories with sentiments more relevant to contemporary life, as inLabyrinth,[111]My Neighbor Totoro,Happily N'Ever After,and the films ofMichel Ocelot.[112]

Other works have retold familiar fairy tales in a darker, more horrific or psychological variant aimed primarily at adults. Notable examples areJean Cocteau'sBeauty and the Beast[113]andThe Company of Wolves,based onAngela Carter's retelling ofLittle Red Riding Hood.[114]Likewise,Princess Mononoke,[115]Pan's Labyrinth,[116]Suspiria,andSpike[117]create new stories in this genre from fairy tale and folklore motifs.

In comics and animated TV series,The Sandman,Revolutionary Girl Utena,Princess Tutu,FablesandMÄRall make use of standard fairy tale elements to various extents but are more accurately categorised asfairytale fantasydue to the definite locations and characters which a longer narrative requires.

A more modern cinematic fairy tale would beLuchino Visconti'sLe Notti Bianche,starringMarcello Mastroiannibefore he became a superstar. It involves many of the romantic conventions of fairy tales, yet it takes place in post-World War IIItaly, and it ends realistically.

In recent years, Disney has been dominating the fairy tale film industry by remaking their animated fairy tale films into live action. Examples includeMaleficent(2014),Cinderella(2015),Beauty and the Beast(2017) and so on.

Motifs

[edit]

Any comparison of fairy tales quickly discovers that many fairy tales have features in common with each other. Two of the most influential classifications are those ofAntti Aarne,as revised byStith Thompsoninto theAarne-Thompson classification system,andVladimir Propp'sMorphology of the Folk Tale.

Aarne-Thompson

[edit]This system groups fairy and folk tales according to their overall plot. Common, identifying features are picked out to decide which tales are grouped together. Much therefore depends on what features are regarded as decisive.

For instance, tales likeCinderella—in which a persecuted heroine, with the help of thefairy godmotheror similarmagical helper,attends an event (or three) in which she wins the love of a prince and is identified as his true bride—are classified as type 510, the persecuted heroine. Some such tales areThe Wonderful Birch;Aschenputtel;Katie Woodencloak;The Story of Tam and Cam;Ye Xian;Cap O' Rushes;Catskin;Fair, Brown and Trembling;Finette Cendron;Allerleirauh.

Further analysis of the tales shows that inCinderella,The Wonderful Birch,The Story of Tam and Cam,Ye Xian,andAschenputtel,the heroine is persecuted by her stepmother and refused permission to go to the ball or other event, and inFair, Brown and TremblingandFinette Cendronby her sisters and other female figures, and these are grouped as 510A; while inCap O' Rushes,Catskin,andAllerleirauh,the heroine is driven from home by her father's persecutions, and must take work in a kitchen elsewhere, and these are grouped as 510B. But inKatie Woodencloak,she is driven from home by her stepmother's persecutions and must take service in a kitchen elsewhere, and inTattercoats,she is refused permission to go to the ball by her grandfather. Given these features common with both types of 510,Katie Woodencloakis classified as 510A because the villain is the stepmother, andTattercoatsas 510B because the grandfather fills the father's role.

This system has its weaknesses in the difficulty of having no way to classify subportions of a tale as motifs.Rapunzelis type 310 (The Maiden in the Tower), but it opens with a child being demanded in return for stolen food, as doesPuddocky;butPuddockyis not a Maiden in the Tower tale, whileThe Canary Prince,which opens with a jealous stepmother, is.

It also lends itself to emphasis on the common elements, to the extent that the folklorist describesThe Black Bull of Norrowayas the same story asBeauty and the Beast.This can be useful as a shorthand but can also erase the coloring and details of a story.[118]

Morphology

[edit]

Vladimir Proppspecifically studied a collection ofRussian fairy tales,but his analysis has been found useful for the tales of other countries.[119][page needed]Having criticized Aarne-Thompson type analysis for ignoring what motifsdidin stories, and because the motifs used were not clearly distinct,[120]he analyzed the tales for thefunctioneach character and action fulfilled and concluded that a tale was composed of thirty-one elements ('functions') and seven characters or 'spheres of action' ('the princess and her father' are a single sphere). While the elements were not all required for all tales, when they appeared they did so in an invariant order – except that each individual element might be negated twice, so that it would appearthree times,as when, inBrother and Sister,the brother resists drinking from enchanted streams twice, so that it is the third that enchants him.[121]Propp's 31 functions also fall within six 'stages' (preparation, complication, transference, struggle, return, recognition), and a stage can also be repeated, which can affect the perceived order of elements.

One such element is thedonorwho gives the hero magical assistance, often after testing him.[122]InThe Golden Bird,the talking fox tests the hero by warning him against entering an inn and, after he succeeds, helps him find the object of his quest; inThe Boy Who Drew Cats,the priest advised the hero to stay in small places at night, which protects him from an evil spirit; inCinderella,the fairy godmother gives Cinderella the dresses she needs to attend the ball, as their mothers' spirits do inBawang Putih Bawang MerahandThe Wonderful Birch;inThe Fox Sister,aBuddhistmonk gives the brothers magical bottles to protect against thefox spirit.The roles can be more complicated.[123]InThe Red Ettin,the role is split into the mother—who offers the hero the whole of a journey cake with her curse or half with her blessing—and when he takes the half, a fairy who gives him advice; inMr Simigdáli,the sun, the moon, and the stars all give the heroine a magical gift. Characters who are not always the donor can act like the donor.[124]InKallo and the Goblins,the villain goblins also give the heroine gifts, because they are tricked; inSchippeitaro,the evil cats betray their secret to the hero, giving him the means to defeat them. Other fairy tales, such asThe Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was,do not feature the donor.

Analogies have been drawn between this and the analysis of myths into thehero's journey.[125]

Interpretations

[edit]Many fairy tales have been interpreted for their (purported) significance. One mythological interpretation saw many fairy tales, includingHansel and Gretel,Sleeping Beauty,andThe Frog King,assolar myths;this mode of interpretation subsequently became rather less popular.[126]Freudian,Jungian,and otherpsychologicalanalyses have also explicated many tales, but no mode of interpretation has established itself definitively.[127][page needed]

Specific analyses have often been criticized[by whom?]for lending great importance to motifs that are not, in fact, integral to the tale; this has often stemmed from treating one instance of a fairy tale as the definitive text, where the tale has been told and retold in many variations.[128]In variants ofBluebeard,the wife's curiosity is betrayed bya blood-stained key,byan egg's breaking,or bythe singing of a rose she wore,without affecting the tale, but interpretations of specific variants have claimed that the precise object is integral to the tale.[129]

Other folklorists have interpreted tales as historical documents. Many[quantify]German folklorists, believing the tales to have preserved details from ancient times, have used the Grimms' tales to explain ancient customs.[86]

One approach sees the topography of European Märchen as echoing the period immediately following thelast Ice Age.[130] Other folklorists have explained the figure of the wicked stepmother in a historical/sociological context: many women did die in childbirth, their husbands remarried, and the new stepmothers competed with the children of the first marriage for resources.[131]

In a 2012 lecture,Jack Zipesreads fairy tales as examples of what he calls "childism". He suggests that there are terrible aspects to the tales, which (among other things) have conditioned children to accept mistreatment and even abuse.[132]

Fairy tales in music

[edit]Fairy tales have inspired music, namely opera, such as the FrenchOpéra féerieand the GermanMärchenoper.French examples include Gretry'sZémire et Azor,and Auber'sLe cheval de bronze,German operas are Mozart'sDie Zauberflöte,Humperdinck'sHänsel und Gretel,Siegfried Wagner'sAn allem ist Hütchen schuld!,which is based on many fairy tales, and Carl Orff'sDie Kluge.

Ballet, too, is fertile ground for bringing fairy tales to life.Igor Stravinsky's first ballet,The Firebirduses elements from various classic Russian tales in that work.

Even contemporary fairy tales have been written for the purpose of inspiration in the music world. "Raven Girl" byAudrey Niffeneggerwas written to inspire a new dance for the Royal Ballet in London. The song "Singring and the Glass Guitar" by the American band Utopia, recorded for their album "Ra", is called "An Electrified Fairytale". Composed by the four members of the band, Roger Powell, Kasim Sulton, Willie Wilcox and Todd Rundgren, it tells the story of the theft of the Glass Guitar by Evil Forces, which has to be recovered by the four heroes.

Compilations

[edit]Authors and works:

From many countries

[edit]- García Carcedo, Pilar (2020):Entre brujas y dragones. Travesía comparativa por los cuentos tradicionales del mundo[133]

- Andrew Lang'sColor Fairy Books(1890–1913)

- Wolfram Eberhard(1909–1989)

- Howard Pyle'sThe Wonder Clock

- Ruth Manning-Sanders(Wales,1886–1988)

- World Tales(United Kingdom, 1979) byIdries Shah

- Richard Dorson(1916–1981)

- The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales(United States, 2002) byMaria Tatar

Italy

[edit]- Pentamerone(Italy, 1634–1636) byGiambattista Basile

- Giovanni Francesco Straparola(Italy, 16th century)

- Giuseppe Pitrè,Italian collector of folktales from his nativeSicily(Italy, 1841–1916)

- Laura Gonzenbach,Swiss collector of Sicilian folk tales (Switzerland,1842–1878)

- Domenico Comparetti,Italian scholar (Italy, 1835–1927)

- Thomas Frederick Crane,American lawyer (United States, 1844–1927)

- Emma Perodi,Italian writer, author of theCasentinianfolk tales (Italy, 1850–1918)

- Luigi Capuana,Italian author of literaryfiabe

- Italian Folktales(Italy, 1956) byItalo Calvino

France

[edit]- Charles Perrault(France, 1628–1703)

- Eustache Le Noble,French writer of literary fairy tales (France, 1646–1711)

- Madame d'Aulnoy(France, 1650–1705)

- Emmanuel Cosquin,French collector of Lorraine fairy tales and one of the earliest tale comparativists (France, 1841–1919)

- Paul Sébillot,collector of folktales fromBrittany,France (France, 1843–1918)

- François-Marie Luzel,French collector of Brittany folktales (France, 1821–1895)

- Charles Deulin,French author and folklorist (France, 1827–1877)

- Édouard René de Laboulaye,French jurist, poet and publisher of folk tales and literary fairy tales

- Henri Pourrat,French collector of Auvergne folklore (1887–1959)

- Achille Millien,collector of Nivernais folklore (France, 1838–1927)

- Paul Delarue,establisher of the French folktale catalogue (France, 1889–1956)

Germany

[edit]- Grimms' Fairy Tales(Germany, 1812–1857)

- Johann Karl August Musäus,German writer ofVolksmärchen der Deutschen(5 volumes; 1782–1786)

- Wilhelm Hauff,German author and novelist

- Heinrich Pröhle,collector of Germanic language folktales

- Franz Xaver von Schönwerth(Germany, 1810–1886)

- Adalbert Kuhn,German philologist and folklorist (Germany, 1812–1881)

- Alfred Cammann(1909–2008), 20th century collector of fairy tales

Belgium

[edit]- Charles Polydore de Mont(Pol de Mont) (Belgium,1857–1931)

United Kingdom and Ireland

[edit]- Joseph Jacobs's two books ofCeltic Fairytalesand two books ofEnglish Folktales(1854–1916)

- Alan Garner's Book of British Fairy Tales(United Kingdom, 1984) byAlan Garner

- Old English fairy talesby ReverendSabine Baring-Gould(1895)

- Popular Tales of the West Highlands(Scotland,1862) byJohn Francis Campbell

- Jeremiah Curtin,collector of Irish folktales and translator of Slavic fairy tales (Ireland, 1835–1906)

- Patrick Kennedy,Irish educator and folklorist (Ireland, ca. 1801–1873)

- Séamus Ó Duilearga,Irish folklorist (Ireland, 1899–1980)

- Kevin Danaher,Irish folklorist (Ireland, 1913-2002)Folktales from the Irish Countryside

- W. B. Yeats,Irish poet and publisher of Irish folktales

- Peter and the Piskies:Cornish Folk and Fairy Tales(United Kingdom, 1958), byRuth Manning-Sanders

Scandinavia

[edit]- Hans Christian Andersen,Danish author of literary fairy tales (Denmark,1805–1875)

- Helena Nyblom,Swedish author of literary fairy tales (Sweden, 1843–1926)

- Norwegian Folktales(Norway,1845–1870) byPeter Christen AsbjørnsenandJørgen Moe

- Svenska folksagor och äfventyr(Sweden, 1844–1849) byGunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius

- August Bondeson,collector of Swedish folktales (1854–1906)

- Jyske FolkeminderbyEvald Tang Kristensen(Denmark,1843–1929)

- Svend Grundtvig,Danish folktale collector (Denmark,1824–1883)

- Benjamin Thorpe,English scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature and translator of Nordic and Scandinavian folktales (1782–1870)

- Jón Árnason,collector of Icelandic folklore

- Adeline Rittershaus,German philologist and translator of Icelandic folktales

Estonia, Finland and Baltic Region

[edit]- Suomen kansan satuja ja tarinoita(Finland,1852–1866) byEero Salmelainen

- August Leskien,German linguist and collector of Baltic folklore (1840–1916)

- William Forsell Kirby,English translator of Finnish folklore and folktales (1844–1912)

- Jonas Basanavičius,collector of Lithuanian folklore (1851–1927)

- Mečislovas Davainis-Silvestraitis,collector of Lithuanian folklore (1849–1919)

- Pēteris Šmits,Latvian ethnographer (1869–1938)

Russia

[edit]- Narodnye russkie skazki(Russia, 1855–1863) byAlexander Afanasyev

Czechia and Slovakia

[edit]- Božena Němcová,writer and collector of Czech fairy tales (1820–1862)

- Alfred Waldau,editor and translator of Czech fairy tales

- Jan Karel Hraše,writer and publisher of Czech fairy tales

- František Lazecký,publisher ofSilesianfairy tales (Slezské pohádky) (1975–1977)

- Karel Jaromír Erben,poet, folklorist and publisher of Czech folktales (1811–1870)

- August Horislav Škultéty,Slovak writer (1819–1895)

- Pavol Dobšinský,collector ofSlovakfolktales (1828–1885)

- Albert Wratislaw,collector of Slavic folktales

Ukraine

[edit]- Ivan Franko,Ukrainian poet, novelist, playwright, creator of many Ukrainian folk and fairy tales (1856–1916)

- Yevhen Hrebinka,Ukrainian romantic prose writer and philanthropist, collector of numerous Ukrainian folktales and proverbs (1812–1848)

- Mykhailo Maksymovych,Ukrainian professor, encyclopedist, folklorist and ethnographer (1804–1873)

- Levko Borovykovsky,Ukrainian romantic poet, folklorist and ethnographer, recorder of Ukrainian legends and fairy tales (1806–1889)

- Petro Hulak-Artemovsky,Ukrainian poet and fable writer, including fable-tales (1790–1865)

- Osyp Bodyanskyi,Ukrainian philologist and folklorist, collector of Ukrainian fairy tales (1808-1877)

Poland

[edit]- Oskar Kolberg,Polish ethnographer who compiled several Polish folk and fairy tales (1814–1890)

- Zygmunt Gloger,Polish historian and ethnographer (1845–1910)

- Bolesław Leśmian,Polish poet (1877–1937)

- Kornel Makuszyński,Polish writer of children's literature and tales (1884–1953)

Romania

[edit]- Legende sau basmele românilor(Romania,1874) byPetre Ispirescu

- QueenElisabeth of Wied's Romanian fairy tales, penned under nom de plumeCarmen Sylva[134]

- Arthur(1814-1875) and Albert Schott (1809-1847), German folklorists and collectors of Romanian fairy tales

- I. C. Fundescu(1836–1904)

- Ion Creangă,Moldavian/Romanian writer, raconteur and schoolteacher (1837-1889)

- Ioan Slavici,Romanian writer and journalist (1848–1925)

- G. Dem. Teodorescu,Wallachian/Romanian folklorist (1849–1900)

- Ion Pop-Reteganul,Romanian folklorist (1853–1905)

- Lazăr Șăineanu,Romanian folklorist (1859–1934)

- Dumitru Stăncescu,Romanian folklorist (1866–1899)

Balkan Area and Eastern Europe

[edit]- Louis Léger,French translator of Slavic fairy tales (France, 1843–1923)

- Johann Georg von Hahn,Austrian diplomat and collector of Albanian and Greek folklore (1811–1869)

- Auguste Dozon,French scholar and diplomat who studied Albanian folklore (1822–1890)

- Robert Elsie,Canadian-born German Albanologist (Canada, 1950–2017)

- Donat Kurti,Albanian franciscan friar, educator, scholar and folklorist (1903–1983)

- Anton Çetta,Albanian folklorist, academic and university professor from Yugoslavia (1920–1995)

- Lucy Garnett,British traveller and folklorist on Turkey and Balkanic folklore (1849–1934)

- Francis Hindes Groome,English scholar ofRomani populations(England, 1851–1902)

- Vuk Karadžić,Serbian philologist (Serbia,1787–1864)

- Elodie Lawton,British writer and translator of Serbian folktales (1825–1908)

- Friedrich Salomon Krauss,collector of South Slavic folklore

- Gašper Križnik(1848–1904), collector of Slovenian folktales

Hungary

[edit]- Elek Benedek,Hungarian journalist and collector of Hungarian folktales

- János Erdélyi,poet, critic, author, philosopher who collected Hungarian folktales

- Gyula Pap,ethographer who contributed to the collectionFolk-tales of the Magyars

- The Hungarian Fairy Book,by Nándor Pogány (1913).[135]

- Old Hungarian Fairy Tales(1895), by CountessEmma Orczyand Montague Barstow.

Spain and Portugal

[edit]- Fernán Caballero(Cecilia Böhl de Faber) (Spain, 1796–1877)

- Francisco Maspons y Labrós(Spain, 1840–1901)

- Antoni Maria Alcover i Sureda,priest, writer and collector of folktales inCatalanfrom Mallorca (Majorca,1862–1932)

- Julio Camarena,Spanish folklorist (1949–2004)

- Teófilo Braga,collector of Portuguese folktales (Portugal,1843–1924)

- Zófimo Consiglieri Pedroso,Portuguese folklorist (Portugal,1851–1910)

- Wentworth Webster,collector of Basque folklore

- Elsie Spicer Eells,researcher on Iberian folklore (Portuguese and Brazilian)

Armenia

[edit]- Karekin Servantsians(Garegin Sruandzteants'; Bishop Sirwantzdiants), ethnologue and clergyman; publisher ofHamov-Hotov(1884)

- Hovhannes Tumanyan,Armenian poet and writer who reworked folkloric material into literary fairy tales (1869–1923)

Middle East

[edit]- Antoine Galland,French translator of theArabian Nights(France, 1646–1715)

- Gaston Maspero,French translator of Egyptian and Middle Eastern folktales (France, 1846–1916)

- Hasan M. El-Shamy,establisher of a catalogue classification of Arab and Middle Eastern folktales

- Amina Shah,British anthologiser of Sufi stories and folk tales (1918–2014)

- Raphael Patai,scholar of Jewish folklore (1910–1996)

- Howard Schwartz,collector and publisher of Jewish folktales (1945–)

- Heda Jason,Israeli folklorist

- Dov Noy,Israeli folklorist (1920–2013)

Turkey

[edit]- Billur Köşk,compilation of Turkish Anatolian stories

- Ignác Kúnos,Hungarian Turkologist and folklorist (1860-1845)

- Pertev Naili Boratav,Turkish folklorist (1907–1998)

- Kaloghlan(Turkey,1923) byZiya Gökalp

Iran

[edit]- Arthur Christensen,German Iranist and publisher of Iranian folktales (1875–1945)

- Fazl'ollah Mohtadi Sobhi,Iranian author and publisher of folktales (1897–1962)

Indian Subcontinent

[edit]- Panchatantra(India, 3rd century BC)

- Kathasaritsagara,compilation of Indian folklore made bySomadevain the 11th century CE

- Madanakamaraja Katha,collection of South Indian folktales

- Burhi Aair Sadhu,collection of Assamese folktales

- Thakurmar Jhuli,collection of Bengali folktales

- Lal Behari Dey,reverend and recorder of Bengali folktales (India, 1824–1892)

- James Hinton Knowles,missionary and collector ofKashmirifolklore

- Maive Stokes,Indian-born British author (1866–1961)

- Joseph Jacobs's book ofIndian Fairy Tales(1854–1916)

- Natesa Sastri's collection of Tamil folklore (India) and translation ofMadanakamaraja Katha

- Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon,three volumes byH. Parker(1910)

- PanditRam Gharib Chaubeand British orientalistWilliam Crooke

- Verrier Elwin,ethographer and collector of Indian folk tales (1902–1964)

- A. K. Ramanujan,poet and scholar of Indian literature (1929–1993)

- Santal Folk Tales,three volumes byPaul Olaf Bodding(1925–29)

- Shobhanasundari Mukhopadhyay(1877–1937), Indian author and collector of folktales

America

[edit]- Marius Barbeau,Canadian folklorist (Canada, 1883–1969)

- Geneviève Massignon,scholar and publisher of French Acadian folklore (1921–1966)

- Carmen Roy,Canadian folklorist (1919–2006)

- Joel Chandler Harris'sUncle Remusseries of books

- Tales from the Cloud Walking Country,by Marie Campbell

- Ruth Ann Musick,scholar of West Virginian folklore (1897–1974)

- Vance Randolph,folklorist who studied the folklore of theOzarks(1892–1980)

- Cuentos populares mexicanos(Mexico, 2014) byFabio Morábito

- Rafael Rivero Oramas, collector of Venezuelan tales. Author ofEl mundo de Tío Conejo,collection of Tío Tigre and Tío Conejo tales.

- Américo Paredes,author specialized in folklore from Mexico and the Mexican-American border (1915–1999)

- Elsie Clews Parsons,American anthropologist and collector of folktales from Central American countries (New York City, 1875–1941)

- John Alden Mason,American linguist and collector of Porto Rican folklore (1885–1967)

- Aurelio Macedonio Espinosa Sr.,scholar of Spanish folklore (1880–1958)

Brazil

[edit]- Sílvio Romero,Brazilian lawyer and folktale collector (Brazil, 1851–1914)

- Luís da Câmara Cascudo,Brazilian anthropologist and ethnologist (Brazil, 1898–1986)

- Lindolfo Gomes,Brazilian folklorist (1875–1953)

- Marco Haurélio,contemporary writer and folklorist, author ofContos e Fábulas do BrasilandContos Folclóricos Brasileiros.

South Korea

[edit]- Baek Hee-na,author of "The Cloud Bread" (South Korea, 1971–)

- Hwang Seon-mi,author of "Hen out of the yard" (South Korea, 1963–)

Africa

[edit]- Hans Stumme,scholar and collector of North African folklore (1864–1936)

- Sigrid Schmidt,folklorist; known for her voluminousAfrika erzählt( "Africa Narrates" ) series. The ten volumes are tales (with extensive commentary) collected by the author during 1959-1962 and 1972-1997 (volumes 1 to 7 in German, volumes 8 to 10 in English), mostly inNamibia.[136]

Asia

[edit]- Kunio Yanagita(Japan, 1875–1962)

- Seki Keigo,Japanese folklorist

- Lafcadio Hearn

- Yei Theodora Ozaki,translator of Japanese folk tales (1870–1932)

- Dean Fansler,professor and scholar of Filipino folklore

Miscellaneous

[edit]- Mixed Up Fairy Tales

- Fairy Tales(United States, 1965) byE. E. Cummings

- Fairy Tales, Now First Collected: To Which are Prefixed Two Dissertations: 1. On Pygmies. 2. On Fairies(England, 1831) byJoseph Ritson

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Scholars John Th. Honti and Gédeon Huet asserted the existence of fairy tales in ancient and medieval literature, as well as in classical mythology.[39][40]

- ^Even further back, according to professor Berlanga Fernández, elements of international "Märchen" show "exact parallels and themes (...) that seem to be common with Greek folklore and later tradition".[41]

- ^FolkloristAlexander Haggerty Krappeargued that most of historical variants of tale types are traceable to the Middle Ages, and some are attested in literary works ofclassical antiquity.[45]Likewise, Francis Lee Utley showed that medievalCeltic literatureandArthurian mythoscontain recognizable motifs of tale types described in the international index.[46]

- ^For a comprehensive introduction into fairy tale interpretation, and main terms of Jungian Psychology (Anima, Animus, Shadow) seeFranz 1970.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Grimm Brothers' Children's and Household Tales (Grimms' Fairy Tales)".sites.pitt.edu.Retrieved22 October2024.

- ^Jorgensen, Jeana (2022).Fairy Tales 101: An Accessible Introduction to Fairy Tales.Fox Folk Press. 372 pages.ISBN979-8985159233.

- ^Bettelheim 1989,p.25.

- ^Thompson, Stith (1972). "Fairy Tale". In Leach, Maria; Fried, Jerome (eds.).Funk & Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology & Legend.Funk & Wagnalls.ISBN978-0-308-40090-0.

- ^Martin, Gary."'Fairy-tale ending' – the meaning and origin of this phrase ".Phrasefinder.Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2020.Retrieved21 August2020.

- ^Orenstein 2002,p. 9.

- ^Gray, Richard (5 September 2009)."Fairy tales have ancient origin".The Telegraph.Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2009.

- ^ab"Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say".BBC News.20 January 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 3 January 2018.Retrieved20 January2016.

- ^Blakemore, Erin (20 January 2016)."Fairy Tales Could Be Older Than You Ever Imagined".Smithsonion Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2019.Retrieved4 March2019.

- ^Jacobs, Joseph (1892)...p. 230 – viaWikisource.

- ^abDavidson, Hilda Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (2006).A companion to the fairy tale.Boydell & Brewer. p. 39.ISBN978-0-85991-784-1.

- ^Thompson 1977,p. 8.

- ^Byatt 2004,p. xviii.

- ^Heiner, Heidi Anne."What Is a Fairy Tale?".Sur La Lune.Archivedfrom the original on 15 August 2020.

- ^abcWindling, Terri (2000)."Les Contes de Fées: The Literary Fairy Tales of France".Realms of Fantasy.Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^Propp 1968,p. 5.

- ^Propp 1968,p. 19.

- ^Swann Jones 1995,p. 15.

- ^Thompson 1977,p. 55.

- ^abTolkien 1966,p. 15.

- ^Tolkien 1966,pp. 10–11.

- ^Swann Jones 1995,p. 8.

- ^Jones, J."Psychoanalysis and Fairy-Tales".Freud File.The Romanian Association for Psychoanalysis Promotion.Archivedfrom the original on 10 November 2012.Retrieved13 March2013.

- ^Calvino, Italo(1988).Six Memos for the Next Millennium.Harvard University Press. pp. 36–37.ISBN0-674-81040-6.

- ^"Märchen".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.Retrieved22 September2022.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^Healy, Marti (19 January 2019)."Marti Healy: Begin anywhere".Aiken Standard.Archivedfrom the original on 30 January 2023.Retrieved30 January2023.

- ^abZipes, Jack (2002b).Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales.Le xing ton: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 28.ISBN978-0-8131-7030-5.

- ^Zipes 2001,pp. xi–xii.

- ^Zipes 2001,p. 858.

- ^Attebery 1980,p. 83.

- ^Martin 2002,pp. 38–42.

- ^abSwann Jones 1995,p. 35.

- ^Attebery 1980,p. 5.

- ^Zipes 2001,p. xii.

- ^Zipes, Jack (2013).Fairy Tale as Myth/Myth as Fairy Tale.University of Kentucky Press. pp. 20–21.ISBN978-0-8131-0834-6.

- ^abZipes 2001,p. 846.

- ^Degh 1988,p. 73.

- ^"Kagerou Bunko"(PDF).International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB).

... many writers in those countries were inspired to regardJiandeng Xinhuaas the supreme model for composing fiction.

- ^Honti, John Th. (1936). "Celtic Studies and European Folk-Tale Research".Béaloideas.6(1): 33–39.doi:10.2307/20521905.JSTOR20521905.

- ^Krappe, Alexander Haggerty (1925). "Review of Les contes popularies".Modern Language Notes.40(7): 429–431.doi:10.2307/2914006.JSTOR2914006.

- ^Berlanga Fernández, Inmaculada (4 December 2017). "Temática folclórica en la Literatura asiática (Oriente Extremo). Relación con los mitos griegos" [Folk themes in Asian Literature (Far East). Relationship to Greek myths].Aldaba(in Spanish) (31): 239–252.doi:10.5944/aldaba.31.2001.20465(inactive 3 April 2024).

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^abcdefghijHeiner, Heidi Anne."Fairy Tale Timeline".Sur La Lune.Archivedfrom the original on 15 August 2020.

- ^abRoberts, Moss, ed. (1979). "Introduction".Chinese Fairy Tales & Fantasies.Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. xviii.ISBN0-394-73994-9.

- ^Szoverffy, Joseph (July 1960). "Some Notes on Medieval Studies and Folklore".The Journal of American Folklore.73(289): 239–244.doi:10.2307/537977.JSTOR537977.

- ^Krappe, Alexander Haggerty (1962).The Science of Folklore.New York: Barnes & Noble. pp. 14–15.OCLC492920.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Utley, Francis Lee (1964). "Arthurian Romance and International Folktale Method".Romance Philology.17(3): 596–607.JSTOR44939518.

- ^Bošković-Stulli, Maja (1962)."Sižei narodnih bajki u Hrvatskosrpskim epskim pjesmama"[Subjects of folk tales in Croato-Serbian epics].Narodna umjetnost: Hrvatski časopis za etnologiju i folkloristiku(in Croatian).1(1): 15–36.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2021.Retrieved20 April2021.

- ^Zipes 2007,p. 12.

- ^Mitakidou, Soula; Manna, Anthony L.; Kanatsouli, Melpomene (2002).Folktales from Greece: A Treasury of Delights.Greenwood Village, Colorado: Libraries Unlimited. p. 100.ISBN1-56308-908-4.

- ^Swann Jones 1995,p. 38.

- ^Windling, Terri."White as Ricotta, Red as Wine: The Magical Lore of Italy".Journal of Mythic Arts.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2022.Retrieved19 August2022.

- ^Calvino 1980,p. 738.

- ^Fujita, Yuken (1954)."Liêu Trai Chí Dị nghiên cứu tự nói: Đặc に Bồ Tùng Linh の chấp bút thái độ に liền いて"[Introduction to the study of "liao chai chih i" (Ryosai shii): with special reference to the author's attitude].Nghệ văn nghiên cứu [Geibun kenkyū](in Japanese) (3): 49–61.ISSN0435-1630.Archivedfrom the original on 5 December 2022.CRID1050282813926397312

- ^Zipes 2007,pp. 38–42.

- ^Swann Jones 1995,pp. 38–39.

- ^Swann Jones 1995,p. 40.

- ^Murphy, G. Ronald (2000).The Owl, The Raven, and the Dove: The Religious Meaning of the Grimms' Magic Fairy Tales.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-515169-0.

- ^Zipes 2007,p. 77.

- ^Degh 1988,pp. 66–67.

- ^Opie, Iona;Opie, Peter(1974).The Classic Fairy Tales.Oxford University Press. p. 17.ISBN978-0-19-211559-1.

- ^Yolen, Jane(2000).Touch Magic.Little Rock, Arkansas: August House. p. 22.ISBN0-87483-591-7.

- ^Lang, Andrew (1904)."Preface".The Brown Fairy Book.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2007.

- ^Ozaki, Yei Theodora."Preface".Japanese Fairy Tales– via Sur La Lune.

- ^Clute & Grant 1997,pp. 26–27, "Hans Christian Andersen".

- ^Clute & Grant 1997,p. 604, "George MacDonald".

- ^Orenstein 2002,pp. 77–78.

- ^Zipes 2001,p. 845.

- ^Jacobs, Joseph (1895)..– viaWikisource.

- ^Calvino 1980,p. xx.

- ^Velten 2001,p. 962.

- ^Velten 2001,pp. 966–967.

- ^Calvino 1980,p. xxi.

- ^Hatt, Gudmund (1949).Asiatic influences in American folklore.København: I kommission hos ejnar Munksgaard. pp. 94–96, 107.OCLC21629218.

- ^Berezkin, Yuri (2010)."Sky-maiden and world mythology".Iris.31(31): 27–39.doi:10.35562/iris.2020.

- ^d'Huy, Julien (2016)."Le motif de la femme-oiseau (T111.2.) et ses origines paléolithiques".Mythologie française(265): 4.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2022.Retrieved21 August2020.

- ^Zipes 2007,p. 1.

- ^abSeifert, Lewis C. (1996). "The marvelous in context: The place of thecontes de féesin late seventeenth-century France ".Fairy Tales, Sexuality, and Gender in France, 1690–1715.Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–98.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511470387.005.ISBN978-0-521-55005-5.

- ^Zipes 2007,p. 47.

- ^Tatar 1987,p. 19.

- ^Tatar 1987,p. 20.

- ^Tatar 1987,p. 32.

- ^Byatt 2004,pp. xlii–xliv.

- ^Tolkien 1966,p. 31.

- ^Briggs 1967,pp. 181–182.

- ^"Charles Dickens's" Frauds on the Fairies "(1 October 1853)".The Victorian Web.23 January 2006.Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2013.Retrieved13 March2013.

- ^abZipes 2002a,p. 48.

- ^Walters, Rebecca (April 2017). "Fairytales, psychodrama and action methods: ways of helping traumatized children to heal".Zeitschrift für Psychodrama und Soziometrie.16(1): 53–60.doi:10.1007/s11620-017-0381-1.S2CID151699614.

- ^Tsitsani, P.; Psyllidou, S.; Batzios, S. P.; Livas, S.; Ouranos, M.; Cassimos, D. (March 2012). "Fairy tales: a compass for children's healthy development – a qualitative study in a Greek island: Fairy tales: a timeless value".Child: Care, Health and Development.38(2): 266–272.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01216.x.PMID21375565.

- ^Jung, C. G. (1969). "The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales".Four Archetypes.Princeton University Press. pp. 83–132.ISBN978-1-4008-3915-5.JSTORj.ctt7sw9v.7.

- ^Franz 1970,pp. 1–2.

- ^*Chesterton, G. K.(1909).Tremendous Trifles.London: Methuen & Co. p. 2nd paragraph in XVII.

- ^Henley, Jon (23 August 2013)."Philip Pullman: 'Loosening the chains of the imagination'".The Guardian.ProQuest1427525203.Archivedfrom the original on 29 August 2020.Retrieved21 August2020.

- ^abClute & Grant 1997,p. 196, "Cinema".

- ^Drazen 2003,pp. 43–44.

- ^Wolf, Eric James (29 June 2008)."Jack Zipes – Are Fairy tales still useful to Children?".The Art of Storytelling Show.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2010.

- ^abSchanoes, Veronica L. (2014).Fairy Tales, Myth, and Psychoanalytic Theory: Feminism and Retelling the Tale.Ashgate.ISBN978-1-4724-0138-0.[page needed]

- ^Zipes 2007,pp. 24–25.

- ^Clute & Grant 1997,p. 333, "Fairytale".

- ^Martin 2002,p. 41.

- ^abPilinovsky, Helen."Donkeyskin, Deerskin, Allerleirauh, The Reality of the Fairy Tale".Journal of Mythic Arts.Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2022.Retrieved19 August2022.

- ^Briggs 1967,p. 195.

- ^Zipes 2002a,pp. 251–252.

- ^Waggoner, Diana (1978).The Hills of Faraway: A Guide to Fantasy.Atheneum. pp. 22–23.ISBN0-689-10846-X.

- ^Clute & Grant 1997,p. 219, "Commedia Dell'Arte".

- ^Clute & Grant 1997,p. 745, "Pantomime".

- ^"Walt Disney Company is founded".History.Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2021.Retrieved12 December2021.

- ^abFurniss, Maureen (2014). "Classical-Era Disney Studio".Art in Motion, Revised Edition: Animation Aesthetics.Indiana University Press. pp. 107–132.doi:10.2307/j.ctt2005zgm.9.ISBN978-0-86196-945-6.JSTORj.ctt2005zgm.9.

- ^Stone, Kay (July 1981). "Marchen to Fairy Tale: An Unmagical Transformation".Western Folklore.40(3): 232–244.doi:10.2307/1499694.JSTOR1499694.

- ^Tatar 1987,p. 24.

- ^Graham, James (2006)."Baba Yaga in Film".Journal of Mythic Arts.

- ^Scheib, Richard (9 July 2004)."Labyrinth (1986)".Moria.Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^Drazen 2003,p. 264.

- ^Windling, Terri (1995)."Beauty and the Beast".Archived from the original on 15 November 2013.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^Windling, Terri (2004)."The Path of Needles or Pins: Little Red Riding Hood".Archived from the original on 20 September 2013.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^Drazen 2003,p. 38.

- ^Spelling, Ian (25 December 2006)."Guillermo del Toro and Ivana Baquero escape from a civil war into the fairytale land ofPan's Labyrinth".Science Fiction Weekly.Archived fromthe originalon 7 July 2007.Retrieved14 July2007.

- ^"Festival Highlights: 2008 Edinburgh International Film Festival".Variety.13 June 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2014.Retrieved28 April2010.

- ^Tolkien 1966,p. 18.

- ^Propp 1968.

- ^Propp 1968,pp. 8–9.

- ^Propp 1968,p. 74.

- ^Propp 1968,p. 39.

- ^Propp 1968,pp. 81–82.

- ^Propp 1968,pp. 80–81.

- ^Vogler, Christopher (1998).The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers(2nd ed.). M. Wiese Productions. p. 30.ISBN0-941188-70-1.

- ^Tatar 1987,p. 52.

- ^Bettelheim 1989.

- ^Dundes, Alan (1988). "Interpreting Little Red Riding Hood Psychoanalytically". In McGlathery, James M. (ed.).The Brothers Grimm and Folktale.University of Illinois Press.ISBN0-252-01549-5.

- ^Tatar 1987,p. 46.

- ^

Maitland, Sara(2014)."Once upon a time: the lost forest and us".In Kelly, Andrew (ed.).The Importance of Ideas: 16 thoughts to get you thinking.Guardian Shorts. Vol. 10. Guardian Books.ISBN978-1-78356-074-5.Retrieved22 May2016.

As the glaciers of the last ice age retreated (from c. 10,000 BC) forests, of various types, quickly colonised the land and came to cover most of Europe. [...] These forests formed the topography out of which the fairy stories (or as they are better called in German – themarchen), which are one of our earliest and most vital cultural forms, evolved.

- ^Warner, Marina(1995).From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers.Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 213.ISBN0-374-15901-7.

- ^Fischlowitz, Sharon (15 November 2012)."Fairy Tales, Child Abuse, and" Childism ": Presentation by Jack Zipes".University of Minnesota Institute for Advanced Study. Archived fromthe originalon 12 December 2012.

- ^Estudio comparativo y antología de cuentos tradicionales del mundo

- ^Sylva, Carmen (1896). "Tales nr. 1-10".Legends from river & mountain.London: George Allen. pp. 1–148.

- ^Pogány, Nándor; Pogány, Willy (1913).The Hungarian Fairy Book.New York: F. A. Stokes Co.

- ^Afrika erzählt

Sources

[edit]- Attebery, Brian (1980).The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature.Indiana University Press.ISBN0-253-35665-2.

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1989).The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, wonder tale, magic tale.New York: Vintage Books.ISBN0-679-72393-5.

- Briggs, Katharine Mary(1967).The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature.University of Chicago Press.OCLC2843854.

- Byatt, A. S.(2004). "Introduction". In Tatar, Maria (ed.).The Annotated Brothers Grimm.W. W. Norton & Company.ISBN0-393-05848-4.

- Calvino, Italo(1980).Italian Folktales.Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.ISBN0-15-645489-0.

- Clute, John;Grant, John(1997).The Encyclopedia of Fantasy.New York: St Martin's Press.ISBN0-312-15897-1.

- Degh, Linda (1988)."What Did the Grimm Brothers Give To and Take From the Folk?".In McGlathery, James M. (ed.).The Brothers Grimm and Folktale.University of Illinois Press.ISBN0-252-01549-5.

- Drazen, Patrick (2003).Anime Explosion!: The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation.Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press.ISBN1-880656-72-8.

- Franz, Marie-Louise von (1970).An Introduction to the Psychology of Fairytales ".Zurich: Spring Publications.OCLC940275302.

- Martin, Philip (2002).The Writer's Guide to Fantasy Literature: From Dragon's Lair to Hero's Quest.Writer Books.ISBN978-0-87116-195-6.

- Orenstein, Catherine (2002).Little Red Riding Hood Undressed.Basic Books.ISBN0-465-04125-6.

- Propp, Vladimir(1968). Wagner, Louis A. (ed.).Morphology of the Folktale.University of Texas Press.doi:10.7560/783911.ISBN978-0-292-78391-1.JSTOR10.7560/783911.OCLC609066584.

- Swann Jones, Steven (1995).The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of the Imagination.New York: Twayne.ISBN0-8057-0950-9.

- Tatar, Maria (1987).The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales.Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-06722-8.

- Thompson, Stith(1977).The Folktale.University of California Press.ISBN0-520-03537-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R.(1966). "On Fairy-Stories".The Tolkien Reader.Ballantine Books.ISBN978-0-345-25585-3.

- Velten, Harry (2001).The Influences of Charles Perrault'sContes de ma Mère L'oieon German Folklore.InZipes 2001.

- Zipes, Jack,ed. (2001).The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm.W. W. Norton.ISBN0-393-97636-X.

- Zipes, Jack (2002a).The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World.Palgrave Macmillan.ISBN0-312-29380-1.

- Zipes, Jack (2007).When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition.Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-98006-7.

Further reading

[edit]- "Kidnapped by Fairies / The Hitch Hiker".Shakespir.Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2021.Retrieved21 August2020.

- Heidi Anne Heiner,"The Quest for the Earliest Fairy Tales: Searching for the Earliest Versions of European Fairy Tales with Commentary on English Translations"Archived14 August 2020 at theWayback Machine

- Heidi Anne Heiner,"Fairy Tale Timeline"Archived15 August 2020 at theWayback Machine

- Vito Carrassi, "Il fairy tale nella tradizione narrativa irlandese: Un itinerario storico e culturale", Adda, Bari 2008; English edition, "The Irish Fairy Tale: A Narrative Tradition from the Middle Ages to Yeats and Stephens", John Cabot University Press/University of Delaware Press, Roma-Lanham 2012.

- Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson:The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography(Helsinki, 1961)

- Tatar, Maria.The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales.W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.ISBN0-393-05163-3

- Benedek Katalin. "Mese és fordítás idegen nyelvről magyarra és magyarról idegenreArchived17 August 2021 at theWayback Machine".In:Aranyhíd. Tanulmányok Keszeg Vilmos tiszteletére.BBTE Magyar Néprajz és Antropológia Intézet; Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület; Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság. 2017. pp. 1001–1013.ISBN978-973-8439-92-4.(In Hungarian) [for collections of Hungarian folktales].

- Le Marchand, Bérénice Virginie (2005). "Refraining the Early French Fairy Tale: A Selected Bibliography".Marvels & Tales.19(1): 86–122.doi:10.1353/mat.2005.0013.JSTOR41388737.S2CID201788183.

On origin and migration of folktales:

- Bortolini, Eugenio; Pagani, Luca; Crema, Enrico R.; Sarno, Stefania; Barbieri, Chiara; Boattini, Alessio; Sazzini, Marco; da Silva, Sara Graça; Martini, Gessica; Metspalu, Mait; Pettener, Davide; Luiselli, Donata; Tehrani, Jamshid J. (22 August 2017)."Inferring patterns of folktale diffusion using genomic data".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.114(34): 9140–9145.Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9140B.doi:10.1073/pnas.1614395114.JSTOR26487305.PMC5576778.PMID28784786.

- d'Huy, Julien (1 June 2019)."Folk-Tale Networks: A Statistical Approach to Combinations of Tale Types".Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics.13(1): 29–49.doi:10.2478/jef-2019-0003.S2CID198317250.

- Goldberg, Christine (2010). "Strength in Numbers: The Uses of Comparative Folktale Research".Western Folklore.69(1): 19–34.JSTOR25735282.

- Jason, Heda; Kempinski, Aharon (1981). "How Old Are Folktales?".Fabula.22(Jahresband): 1–27.doi:10.1515/fabl.1981.22.1.1.S2CID162398733.

- hÓgáin, Dáithí Ó (2000). "The Importance of Folklore within the European Heritage: Some Remarks".Béaloideas.68:67–98.doi:10.2307/20522558.JSTOR20522558.

- Nakawake, Y.; Sato, K. (2019)."Systematic quantitative analyses reveal the folk-zoological knowledge embedded in folktales".Palgrave Communications.5(161).arXiv:1907.03969.doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0375-x.

- Newell, W. W. (January 1895). "Theories of Diffusion of Folk-Tales".The Journal of American Folklore.8(28): 7–18.doi:10.2307/533078.JSTOR533078.

- Nouyrigat, Vicent. "Contes de fées: leur origine révélée par la génétique". Excelsior publications (2017) inLa Science et la Vie(Paris), édition 1194 (03/2017), pp. 74–80.

- Ross, Robert M.; Atkinson, Quentin D. (January 2016). "Folktale transmission in the Arctic provides evidence for high bandwidth social learning among hunter–gatherer groups".Evolution and Human Behavior.37(1): 47–53.Bibcode:2016EHumB..37...47R.doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.08.001.

- Swart, P. D. (1957). "The Diffusion of the Folktale: With Special Notes on Africa".Midwest Folklore.7(2): 69–84.JSTOR4317635.

- Utley, Francis Lee; Austerlitz, Robert; Bauman, Richard; Bolton, Ralph; Count, Earl W.; Dundes, Alan; Erickson, Vincent; Farmer, Malcolm F.; Fischer, J. L.; Hultkrantz, Åke; Kelley, David H.; Peek, Philip M.; Pretty, Graeme; Rachlin, C. K.; Tepper, J. (1974). "The Migration of Folktales: Four Channels to the Americas [and Comments and Reply]".Current Anthropology.15(1): 5–27.doi:10.1086/201428.JSTOR2740874.S2CID144105176.

- Zaitsev, A. I. (July 1987). "On the Origin of the Wondertale".Soviet Anthropology and Archeology.26(1): 30–40.doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959260130.

External links

[edit]- Once Upon a Time– How Fairy Tales Shape Our Lives, by Jonathan Young, PhD

- Once Upon A Time: Historical and Illustrated Fairy Tales. Special Collections, University of Colorado Boulder