Falcon

| Falcon Temporal range:Late Mioceneto present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Brown falcon(Falco berigora) inVictoria,Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes |

| Family: | Falconidae |

| Subfamily: | Falconinae |

| Genus: | Falco Linnaeus,1758 |

| Type species | |

| Falco subbuteo[1] Linnaeus,1758

| |

| Species | |

|

38; seetext. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Falcons(/ˈfɒlkən,ˈfɔːl-,ˈfæl-/) arebirds of preyin thegenusFalco,which includes about 40species.Some small species of falcons with long, narrowwingsare calledhobbies,[7]and some thathoverwhile hunting are calledkestrels.[7][8]Falcons are widely distributed on all continents of the world exceptAntarctica,though closely related raptors did occur there in theEocene.[9]

Adult falcons have thin, tapered wings, which enable them to fly at high speed and change direction rapidly. Fledgling falcons, in their first year of flying, have longerflight feathers,which make their configuration more like that of a general-purpose bird such as abroadwing.This makes flying easier while still learning the aerial skills required to be effective hunters like the adults.

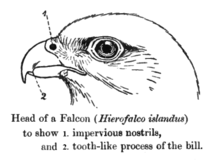

The falcons are the largest genus in the FalconinaesubfamilyofFalconidae,which also includes two other subfamilies comprisingcaracarasand a few other species of "falcons". All these birds kill prey with theirbeaks,using atomial"tooth" on the side of their beaks — unlike thehawks,eaglesand other larger birds of prey from the unrelated familyAccipitridae,who usetalonson their feet.

The largest falcon is thegyrfalconat up to 65 cm (26 in) in length. The smallest falcon species is thepygmy falcon,which measures just 20 cm (7.9 in). As with hawks andowls,falcons exhibitsexual dimorphism,with the females typically larger than the males, thus allowing a wider range of prey species.[10]

As is the case with many birds of prey, falcons have exceptional powers ofvision;thevisual acuityof one species has been measured at 2.6 times that ofhuman eyes.[11]They are incredibly fast fliers, with thePeregrine falconshaving been recorded diving at speeds of 320 km/h (200 mph), making them the fastest-moving creatures on Earth; the fastest recorded dive attained a vertical speed of 390 km/h (240 mph).[12]

Taxonomy[edit]

ThegenusFalcowas introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalistCarl Linnaeusin thetenth editionof hisSystema Naturae.[13]Thetype speciesis themerlin(Falco columbarius).[14]The genus nameFalcoisLate Latinmeaning a "falcon" fromfalx,falcis,meaning "a sickle", referring to the claws of the bird.[15][16]InMiddle EnglishandOld French,the titlefauconrefers generically to several captive raptor species.[17]

The traditional term for a male falcon istercel(British spelling) ortiercel(American spelling), from the Latintertius(third) because of the belief that only one in three eggs hatched a male bird. Some sources give the etymology as deriving from the fact that a male falcon is about one-third smaller than a female[18][19][20](Old French:tiercelet). A falcon chick, especially one reared forfalconry,still in its downy stage, is known as aneyas[21][22](sometimes spelledeyass). The word arose by mistaken division ofOld Frenchun niais,from Latin presumednidiscus(nestling) fromnidus(nest). The technique of hunting with trained captive birds of prey is known asfalconry.

Compared to other birds of prey, thefossilrecord of the falcons is not well distributed in time. For years, the oldest fossils tentatively assigned to this genus were from the LateMiocene,less than 10 million years ago.[23]This coincides with a period in which many modern genera of birds became recognizable in the fossil record. As of 2021, the oldest falconid fossil is estimated to be 55 million years old.[24][25]Given the distribution of fossil and livingFalcotaxa,falcons are probably of North American, African, or possibly Middle Eastern or European origin. Falcons are not closely related to other birds of prey, and theirnearest relativesareparrotsandsongbirds.[26]

Overview[edit]

Falcons are roughly divisible into three or four groups. The first contains thekestrels(probably excepting theAmerican kestrel);[17]usually small and stocky falcons of mainly brown upperside colour and sometimes sexually dimorphic; three African species that are generally gray in colour stand apart from the typical members of this group. Thefoxandgreater kestrelscan be told apart at first glance by their tail colours, but not by much else; they might be very close relatives and are probably much closer to each other than the lesser and common kestrels. Kestrels feed chiefly onterrestrialvertebratesandinvertebratesof appropriate size, such asrodents,reptiles,orinsects.

The second group contains slightly larger (on average) species, the hobbies and relatives. These birds are characterized by considerable amounts of dark slate-gray in their plumage; theirmalarareas are nearly always black. They feed mainly on smaller birds.

Third are the peregrine falcon and its relatives, variably sized powerful birds that also have a black malar area (except some very light colormorphs), and often a black cap, as well. They are very fast birds with a maximum speed of 390 kilometres per hour. Otherwise, they are somewhat intermediate between the other groups, being chiefly medium grey with some lighter or brownish colours on their upper sides. They are, on average, more delicately patterned than the hobbies and, if the hierofalcons are excluded (see below), this group typically contains species with horizontal barring on their undersides. As opposed to the other groups, where tail colour varies much in general but little according toevolutionaryrelatedness,[note 1]the tails of the large falcons are quite uniformly dark grey with inconspicuous black banding and small, white tips, though this is probablyplesiomorphic.These largeFalcospecies feed on mid-sized birds and terrestrial vertebrates.

Very similar to these, and sometimes included therein, are the four or so species ofhierofalcon(literally, "hawk-falcons" ). They represent taxa with, usually, morephaeomelanins,which impart reddish or brown colors, and generally more strongly patterned plumage reminiscent ofhawks.Their undersides have a lengthwise pattern of blotches, lines, or arrowhead marks.

While these three or four groups, loosely circumscribed, are an informal arrangement, they probably contain several distinctcladesin their entirety.

A study ofmtDNAcytochromebsequencedata of some kestrels[17]identified a clade containing the common kestrel and related "malar-striped "species, to the exclusion of such taxa as the greater kestrel (which lacks a malar stripe), the lesser kestrel (which is very similar to the common, but also has no malar stripe), and the American kestrel, which has a malar stripe, but its colour pattern – apart from the brownish back – and also the black feathers behind the ear, which never occur in the true kestrels, are more reminiscent of some hobbies. The malar-striped kestrels apparently split from their relatives in theGelasian,roughly 2.0–2.5 million years ago (Mya), and are seemingly of tropical East African origin. The entire "true kestrel" group—excluding the American species—is probably a distinct and quite youngclade,as also suggested by their numerousapomorphies.

Other studies[27][28][29][30][31]have confirmed that the hierofalcon are amonophyleticgroup–and thathybridizationis quite frequent at least in the larger falcon species. Initial studies of mtDNA cytochromebsequence data suggested that the hierofalcon arebasalamong living falcons.[27][28]The discovery of aNUMTproved this earlier theory erroneous.[29]In reality, the hierofalcon are a rather young group, originating at the same time as the start of the main kestrel radiation, about 2 Mya. Very little fossil history exists for this lineage. However, the present diversity of very recent origin suggests that this lineage may have nearly gone extinct in the recent past.[31][32]

The phylogeny and delimitations of the peregrine and hobby groups are more problematic. Molecular studies have only been conducted on a few species, and the morphologically ambiguous taxa have often been little researched. Themorphologyof thesyrinx,which contributes well to resolving the overallphylogenyof theFalconidae,[33][34]is not very informative in the present genus. Nonetheless, a core group containing the peregrine and Barbary falcons, which, in turn, group with the hierofalcon and the more distantprairie falcon(which was sometimes placed with the hierofalcon, though it is entirely distinctbiogeographically), as well as at least most of the "typical" hobbies, are confirmed to bemonophyleticas suspected.[27][28]

Given that the AmericanFalcospecies of today belong to the peregrine group, or are apparently more basal species, the initially most successfulevolutionary radiationseemingly was aHolarcticone that originated possibly around central Eurasia or in (northern) Africa. One or several lineages were present in North America by theEarly Plioceneat latest.

The origin of today's majorFalcogroups—the "typical" hobbies and kestrels, for example, or the peregrine-hierofalcon complex, or theaplomado falconlineage—can be quite confidently placed from theMiocene-Plioceneboundary through theZancleanandPiacenzianand just into the Gelasian, that is from 2.4 to 5.3 Mya, when the malar-striped kestrels diversified. Some groups of falcons, such as the hierofalcon complex and the peregrine-Barbary superspecies, have only evolved in more recent times; the species of the former seem to be 120,000 years old or so.[31]

Species[edit]

The sequence follows the taxonomic order of Whiteet al.(1996),[35]except for adjustments in the kestrel sequence.

| Image | Common name | Scientific name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Malagasy kestrel | Falco newtoni | Madagascar, Mayotte, and the Comores. |

|

Seychelles kestrel | Falco araeus | Seychelles Islands |

|

Mauritius kestrel | Falco punctatus | Mauritius |

|

Spotted kestrel | Falco moluccensis | Wallacea and Java. |

|

Nankeen kestrelor Australian kestrel | Falco cenchroides | Australia and New Guinea. |

|

Common kestrel | Falco tinnunculus | Widespread in Europe, Asia, and Africa, as well as occasionally reaching the east coast of North America. |

|

Rock kestrel | Falco rupicolus | Northwestern Angola and southern Democratic Republic of Congo to southern Tanzania, and south to South Africa. |

|

Greater kestrel | Falco rupicoloides | Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, parts of Angola and Zambia and in much of South Africa. |

|

Fox kestrel | Falco alopex | South of the Sahara from Mali eastwards as far as Ethiopia and north-west Kenya. It occasionally wanders west to Senegal, the Gambia and Guinea and south to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. |

|

Lesser kestrel | Falco naumanni | Mediterranean across Central Asia into China and Mongolia. |

|

Grey kestrel | Falco ardosiaceus | Ethiopia, western parts of Kenya and Tanzania. |

|

Dickinson's kestrel | Falco dickinsoni | Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi along with north-eastern South Africa. |

|

Banded kestrel | Falco zoniventris | Madagascar |

|

Red-necked falcon | Falco chicquera | Africa, India |

|

Red-footed falcon | Falco vespertinus | Russia, Ukraine and bordering regions. |

|

Amur falcon | Falco amurensis | South-eastern Siberia and Northern China. |

|

Eleonora's falcon | Falco eleonorae | Greece, Cyprus, the Canary Islands, Ibiza and off Spain, Italy, Croatia, Morocco and Algeria. |

|

Sooty falcon | Falco concolor | Northeastern Africa to the southern Persian Gulf region. |

|

American kestrelor "sparrow hawk" | Falco sparverius | Central and western Alaska across northern Canada to Nova Scotia, and south throughout North America, into central Mexico and the Caribbean. |

|

Aplomado falcon | Falco femoralis | Northern Mexico and Trinidad locally to southern South America. |

|

Merlinor "pigeon hawk" | Falco columbarius | Eurasia, North Africa, North America. |

|

Bat falcon | Falco rufigularis | Tropical Mexico, Central and South America, and Trinidad |

|

Orange-breasted falcon | Falco deiroleucus | Southern Mexico to northern Argentina. |

|

Eurasian hobby | Falco subbuteo | Africa, Europe and Asia. |

|

African hobby | Falco cuvierii | Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. |

|

Oriental hobby | Falco severus | Eastern Himalayas and ranges southwards through Indochina to Australasia |

|

Australian hobbyor little falcon | Falco longipennis | Australia |

|

New Zealand falconor kārearea | Falco novaeseelandiae | New Zealand |

|

Brown falcon | Falco berigora | Australia and New Guinea. |

|

Grey falcon | Falco hypoleucos | Australia |

|

Black falcon | Falco subniger | Australia |

|

Lanner falcon | Falco biarmicus | Africa, southeast Europe and just into Asia. |

|

Laggar falcon | Falco jugger | Southeastern Iran, southeastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, through India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and northwestern Myanmar. |

|

Saker falcon | Falco cherrug | Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and China. |

|

Gyrfalcon | Falco rusticolus | Eastern and western Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Iceland and Norway. |

|

Prairie falcon | Falco mexicanus | Western North America. |

|

Peregrine falcon | Falco peregrinus | Cosmopolitan |

|

Taita falcon | Falco fasciinucha | Kenya |

Extinct species[edit]

- Réunion kestrel,Falco duboisi–extinct(about 1700)

Fossil record[edit]

- Falco medius(Late Miocene of Cherevichnyi, Ukraine)[note 2][36][37]

- ?Falcosp. (Late Miocene of Idaho)[note 3]

- Falcosp. (Early[38]Pliocene of Kansas)[39]

- Falcosp. (Early Pliocene of Bulgaria – Early Pleistocene of Spain and Czech Republic)[note 4]

- Falco oregonus(Early/Middle Pliocene of Fossil Lake, Oregon) – possibly not distinct from a living species

- Falco umanskajae(Late Pliocene of Kryzhanovka, Ukraine) – includes "Falco odessanus",anomen nudum[40]

- ?Falco bakalovi(Late Pliocene of Varshets, Bulgaria)[41][42]

- Falco antiquus(Middle Pleistocene of Noailles, France and possibly Horvőlgy, Hungary)[note 5][31]

- Cuban kestrel,Falco kurochkini(Late Pleistocene/Holocene of Cuba, West Indies)

- Falco chowi(China)

- Falco bulgaricus(Late Miocene of Hadzhidimovo, Bulgaria)[43]

Several more paleosubspecies of extant species also been described; see species accounts for these.

"Sushkinia" pliocaenafrom the Early Pliocene of Pavlodar (Kazakhstan) appears to be a falcon of some sort. It might belong in this genus or a closely related one.[36]In any case, the genus nameSushkiniais invalid for this animal because it had already been allocated to a prehistoricdragonflyrelative. In 2015 the bird genus was renamedPsushkinia.[44]

The supposed"Falco" pisanuswas actually a pigeon of the genusColumba,possibly the same asColumba omnisanctorum,which, in that case, would adopt the older species name of the "falcon".[37]TheEocenefossil"Falco" falconellus(or"F." falconella) from Wyoming is a bird of uncertain affiliations, maybe a falconid, maybe not; it certainly does not belong in this genus."Falco" readeiis now considered apaleosubspeciesof theyellow-headed caracara(Milvago chimachima).

See also[edit]

- Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital

- Falconry

- Ra

- Horus

- Khonsu

- National symbols of Kuwait

- National symbols of Saudi Arabia

Notes[edit]

- ^For example, tail colour in thecommonandlesser kestrelsis absolutely identical, yet they do not seem closely related.

- ^IZAN45-4033: leftcarpometacarpus.Small species; possibly closer to kestrels than to peregrine lineage or hierofalcons, but may be more basal altogether due to its age

- ^IMNH27937. Acoracoidof amerlin-sized species. It does not seem close toF. columbariusor the Recent North American species (Becker 1987).

- ^Ahierofalcon(Mlíkovský 2002)? If so, probably not close to the living species, but an earlier divergence that left no descendants; might be more than one species due to large range in time and/or include common ancestor of hierofalcons and peregrine-Barbary complex (Nittingeret al.2005).

- ^Supposedly asaker falconpaleosubspecies(Mlíkovský 2002), but this is not too likely due to the probableEemianorigin of that species.

References[edit]

- ^"Falconidae".aviansystematics.org.The Trust for Avian Systematics.Retrieved25 July2023.

- ^Strickland, H.E. (February 1841)."XLVIII. Commentary on Mr. G R. Gray's 'Genera of Birds.' 8vo. London, 1840".The Annals and Magazine of Natural History.Series 1.6(39): 416.hdl:2027/nnc1.1001656368.Retrieved8 February2024– via HathiTrust.

- ^"Hieracidea Strickland, 1841".WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species.26 April 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 2 January 2022.Retrieved8 February2024.

- ^"FALNOV.pdf"(PDF).New Zealand Birds Online(published 3 September 2020). 6 March 2013.Archived(PDF)from the original on 8 February 2024.Retrieved8 February2024.(Text extracted fromGill, B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. (2010).Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica(4th ed.). Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. pp. 174–176.)

- ^Friedmann, Herbert (1950).The birds of North and Middle America: a descriptive catalog of the higher groups, genera, species, and subspecies of birds known to occur in North America,...Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin, no. 50, part 11. United States Government Printing Office. p. 615.hdl:2027/osu.32435029597671.Retrieved9 February2024– via HathiTrust.

- ^Richmond, Charles W. (1902).List of generic terms proposed for birds during the years 1890 to 1900, inclusive, to which are added names omitted by Waterhouse in his "Index generum avium,"...Proceedings of the United States National Museum. Vol. 24. Washington: Smithsonian Institution / Government Printing Office. p. 685.hdl:2027/coo.31924090189725.Retrieved9 February2024– via HathiTrust.

- ^abOberprieler, Ulrich; Cillié, Burger (2009).The raptor guide of Southern Africa.Game Parks Publishing.ISBN9780620432238.

- ^Sale, Richard (28 July 2016).Falcons (Collins New Naturalist Library, Book 132).HarperCollins UK.ISBN9780007511433.

- ^Cenizo, Marcos; Noriega, Jorge I.; Reguero, Marcelo A. (2016)."A stem falconid bird from the Lower Eocene of Antarctica and the early southern radiation of the falcons".Journal of Ornithology.157(3): 885.doi:10.1007/s10336-015-1316-0.hdl:11336/54190.S2CID15517037.

- ^Krüger, Oliver (2005). "The Evolution of Reversed Sexual Dimorphism in Hawks, Falcons and Owls: a comparative study".Evolutionary Ecology.19(5): 467–486.doi:10.1007/s10682-005-0293-9.S2CID22181702.

- ^Fox, R; Lehmkuhle, S.; Westendorf, D. (1976). "Falcon visual acuity".Science.192(4236): 263–65.Bibcode:1976Sci...192..263F.doi:10.1126/science.1257767.PMID1257767.

- ^"The Speed of Animals" inThe New Book of Knowledge.Grolier Academic Reference. 2003. p. 278.ISBN071720538X

- ^Linnaeus, Carl(1758).Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis(in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 88.

- ^Dickinson, E.C.;Remsen, J.V. Jr.,eds. (2013).The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World.Vol. 1: Non-passerines (4th ed.). Eastbourne, UK: Aves Press. p. 349.ISBN978-0-9568611-0-8.

- ^Jobling, James A. (2010).The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names.London: Christopher Helm. p. 63.ISBN978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^Stevenson, Angus; Brown, Lesley, eds. (2007).Shorter Oxford English dictionary on historical principles(6th. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199206872.OCLC170973920.

- ^abcGroombridge, Jim J.; Jones, Carl G.; Bayes, Michelle K.; van Zyl, Anthony J.; Carrillo, José; Nichols, Richard A.; Bruford, Michael W. (2002). "A molecular phylogeny of African kestrels with reference to divergence across the Indian Ocean".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.25(2): 267–77.Bibcode:2002MolPE..25..267G.doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00254-3.PMID12414309.

- ^Harper, Douglas."tercel".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^"tercel".Dictionary.reference.Retrieved20 March2010.

- ^"tercel", Oxford Dictionary

- ^"eyas".Thefreedictionary.Retrieved20 March2010.

- ^"Dictionary of Difficult Words – eyas".Tiscali.co.uk. 21 September 1964. Archived fromthe originalon 5 January 2009.Retrieved20 March2010.

- ^Li, Zhiheng; Zhou, Zhonghe; Deng, Tao; Li, Qiang; Clarke, Julia A. (4 June 2014)."A falconid from the Late Miocene of northwestern China yields further evidence of transition in Late Neogene steppe communities".Ornithological Advances.131:335–350.

- ^Mayr, Gerald; Kitchener, Andrew C. (1 October 2021)."New fossils from the London Clay show that the Eocene Masillaraptoridae are stem group representatives of falcons (Aves, Falconiformes)".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.41(6).Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E3515M.doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.2083515.ISSN0272-4634.

- ^Kirschbaum, Kari."Falconidae (falcons)".Animal Diversity Web.Retrieved1 May2024.

- ^Suh A, Paus M, Kiefmann M, et al. (2011)."Mesozoic retroposons reveal parrots as the closest living relatives of passerine birds".Nature Communications.2(8): 443–8.Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..443S.doi:10.1038/ncomms1448.PMC3265382.PMID21863010.

- ^abcHelbig, A.J.; Seibold, I.; Bednarek, W.; Brüning, H.; Gaucher, P.; Ristow, D.; Scharlau, W.; Schmidl, D. & Wink, Michael (1994):Phylogenetic relationships among falcon species (genus Falco) according to DNA sequence variation of the cytochrome b gene.In:Meyburg, B.-U. & Chancellor, R.D. (eds.):Raptor conservation today:pp. 593–99

- ^abcWink, Michael; Seibold, I.; Lotfikhah, F. & Bednarek, W. (1998):Molecular systematics of holarctic raptors (Order Falconiformes).In:Chancellor, R.D., Meyburg, B.-U. & Ferrero, J.J. (eds.):Holarctic Birds of Prey:29–48. Adenex & WWGBP

- ^abWink, Michael & Sauer-Gürth, Hedi (2000):Advances in the molecular systematics of African raptors.In:Chancellor, R.D. & Meyburg, B.-U. (eds):Raptors at Risk:135–47. WWGBP/Hancock House, Berlin/Blaine.

- ^Wink, Michael; Sauer-Gürth, Hedi; Ellis, David & Kenward, Robert (2004):Phylogenetic relationships in the Hierofalco complex (Saker-, Gyr-, Lanner-, Laggar Falcon).In:Chancellor, R.D. & Meyburg, B.-U. (eds.):Raptors Worldwide:499–504. WWGBP, Berlin

- ^abcdNittinger, F.; Haring, E.; Pinsker, W.; Wink, Michael; Gamauf, A. (2005)."Out of Africa? Phylogenetic relationships betweenFalco biarmicusand other hierofalcons (Aves Falconidae) "(PDF).Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research.43(4): 321–31.doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2005.00326.x.

- ^Johnson, J.A.; Burnham, K.K.; Burnham, W.A.; Mindell, D.P. (2007)."Genetic structure among continental and island populations of gyrfalcons"(PDF).Molecular Ecology.16(15): 3145–60.Bibcode:2007MolEc..16.3145J.doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03373.x.hdl:2027.42/71471.PMID17651193.S2CID17437176.

- ^Griffiths, Carole S. (1999)."Phylogeny of the Falconidae inferred from molecular and morphological data"(PDF).Auk.116(1): 116–30.doi:10.2307/4089459.JSTOR4089459.

- ^Griffiths, Carole S.; Barrowclough, George F.; Groth, Jeff G.; Mertz, Lisa (2004). "Phylogeny of the Falconidae (Aves): a comparison of the efficacy of morphological, mitochondrial, and nuclear data".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.32(1): 101–09.Bibcode:2004MolPE..32..101G.doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.11.019.PMID15186800.

- ^White, Clayton M.; Olsen, Penny D. & Kiff, Lloyd F. (1994): Family Falconidae.In:del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (editors):Handbook of Birds of the World,Volume 2 (New World Vultures to Guineafowl):216–75, plates 24–28. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.ISBN84-87334-15-6

- ^abBecker, Jonathan J. (1987)."Revision of"Falco" ramentaWetmore and the Neogene evolution of the Falconidae "(PDF).Auk.104(2): 270–76.doi:10.1093/auk/104.2.270.JSTOR4087033.

- ^abMlíkovský, Jirí (2002):Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: EuropeArchived20 May 2011 at theWayback Machine.Ninox Press, Prague

- ^Fox Canyon Local Fauna, 4.3–4.8million years ago:Martin, R.A.; Honey, J.G. & Pelaez-Campomanes, P. (2000):The Meade Basin Rodent Project; a progress report.Kansas Geological Survey Open-file Report 2000-61.Paludicola3(1): 1–32.

- ^UMMPV27159, V29107, V57508-V57510, V57513/V57514 some limb bones. Slightly smaller than amerlinand more robust thanAmerican kestrel,and seems not too distant fromF. columbarius.Feduccia, J. Alan; Ford, Norman L. (1970)."Some birds of prey from the Upper Pliocene of Kansas"(PDF).Auk.87(4): 795–97.doi:10.2307/4083714.JSTOR4083714.

- ^NNPM NAN41-646. Almost complete lefttarsometatarsus.Probably a prehistoric hobby, perhaps less specialized for bird hunting: Sobolev, D.V. (2003):Новый вид плиоценового сокола (Falconiformes, Falconidae)[A new species of Pliocene falcon (Falconiformes, Falconidae)]Vestnik zoologii37 (6): 85–87. [Russian with English abstract]

- ^Boev, Z. 1999.Falco bakalovisp. n. – a Late Pliocene falcon (Falconidae, Aves) from Varshets (W Bulgaria). – Geologica Balcanica, 29 (1–2): 131–35.

- ^Boev, Z. 2011. New fossil record of the Late Pliocene kestrel (Falco bakaloviBoev, 1999) from the type locality in Bulgaria. – Geologica Balcanica, 40 (1–3): 13–30.

- ^Boev, Z. 2011.Falco bulgaricussp. n. (Aves, Falconiformes) from the Middle Miocene of Hadzhidimovo (SW Bulgaria). – Acta zoologica bulgarica, 63 (1): 17–35.

- ^Nikita V. Zelenkov; Evgeny N. Kurochkin (2015). "КЛАСС AVES". In E.N. Kurochkin; A.V. Lopatin; N.V. Zelenkov. Ископаемые позвоночные России и сопредельных стран. Ископаемые рептилии и птицы. Часть 3 / Fossil vertebrates of Russia and adjacent countries. Fossil Reptiles and Birds. Part 3. GEOS. pp. 86–290.ISBN978-5-89118-699-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Fuchs, J.; Johnson, J.A.; Mindell, D.P. (2015). "Rapid diversification of falcons (Aves: Falconidae) due to expansion of open habitats in the Late Miocene".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.82:166–182.Bibcode:2015MolPE..82..166F.doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.010.PMID25256056.

External links[edit]

- Falconidae videoson the Internet Bird Collection, ibc.lynxeds

- The Raptor Resource Project– Peregrine, owl, eagle and osprey cams, facts, and other resources, raptorresource.org

- .New International Encyclopedia.1905.