Fantasy literature

|

| Speculative fiction |

|---|

|

|

Fantasy literatureisliteratureset in animaginary universe,often but not always without any locations, events, or people from the real world.Magic,thesupernaturalandmagical creaturesare common in many of these imaginary worlds. Fantasy literature may be directed at both children and adults.

Fantasyis considered a genre ofspeculative fictionand is distinguished from the genres ofscience fictionandhorrorby the absence of scientific or macabre themes, respectively, though these may overlap. Historically, most works of fantasy were inwritten form,but since the 1960s, a growing segment of the fantasy genre has taken the form offilms,television programs,graphic novels,video games,music and art.

Many fantasy novels originally written for children and adolescents also attract an adult audience. Examples includeAlice's Adventures in Wonderland,theHarry Potterseries,The Chronicles of Narnia,andThe Hobbit.

History[edit]

Beginnings[edit]

Stories involving magic and terrible monsters have existed in spoken forms before the advent of printed literature.Classical mythologyis replete with fantastical stories and characters, the best known (and perhaps the most relevant to modern fantasy) being the works ofHomer(Greek) andVirgil(Roman).[1]

The philosophy ofPlatohas had great influence on the fantasy genre. In the Christian Platonic tradition, the reality of other worlds, and an overarching structure of great metaphysical and moral importance, has lent substance to the fantasy worlds of modern works.[2]

WithEmpedocles(c. 490– c. 430 BC),elementsare often used in fantasy works as personifications of the forces of nature.[3]

Indiahas a long tradition of fantastical stories and characters, dating back toVedic mythology.ThePanchatantra(Fables of Bidpai), which some scholars believe was composed around the 3rd century BC.[4]It is based on older oral traditions, including "animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine".[5]

It was influential in Europe and theMiddle East.It used various animalfablesand magical tales to illustrate the central Indian principles ofpolitical science.Talking animals endowed with human qualities have now become a staple of modern fantasy.[6]

TheBaital Pachisi(Vikram and the Vampire), a collection of various fantasy tales set within aframe storyis, according toRichard Francis BurtonandIsabel Burton,"the germ which culminated in theArabian Nights,and which also inspired theGolden AssofApuleius,(2nd century A.D).Boccacio'sDecamerone(c.1353) thePentamerone(1634, 1636) and all that class of facetious fictitious literature. "[7]

The Book of One Thousand and One Nights(Arabian Nights)from theMiddle Easthas been influential in the West since it was translated from the Arabic into French in 1704 byAntoine Galland.[8]Many imitations were written, especially in France.[9]

TheFornaldarsagas,NorseandIcelandicsagas,both of which are based on ancientoral traditioninfluenced the German Romantics, as well asWilliam Morris,andJ. R. R. Tolkien.[10]TheAnglo-Saxonepic poemBeowulfhas also had deep influence on the fantasy genre; although it was unknown for centuries and so not developed in medieval legend and romance, several fantasy works have retold the tale, such asJohn Gardner'sGrendel.[11]

Celtic folkloreand legend has been an inspiration for many fantasy works.[12]

TheWelshtradition has been particularly influential, owing to its connection to King Arthur and its collection in a single work, the epicMabinogion.[12]One influential retelling of this was the fantasy work ofEvangeline Walton.[13]The IrishUlster CycleandFenian Cyclehave also been plentifully mined for fantasy.[12]Its greatest influence was, however, indirect. Celtic folklore and mythology provided a major source for the Arthurian cycle ofchivalric romance:theMatter of Britain.Although the subject matter was heavily reworked by the authors, these romances developed marvels until they became independent of the original folklore and fictional, an important stage in the development of fantasy.[14]

From the 13th century[edit]

Romance orchivalric romanceis a type ofproseandversenarrativethat reworkedlegends,fairy tales,and history to suit the readers' and hearers' tastes, but byc. 1600they were out of fashion, andMiguel de Cervantesfamouslyburlesquedthem in his novelDon Quixote.Still,the modern image of "medieval"is more influenced by the romance than by any other medieval genre, and the wordmedievalevokes knights, distressed damsels, dragons, and other romantic tropes.[15]

Renaissance[edit]

At the time of theRenaissanceromance continued to be popular, and the trend was to more fantastic fiction. The EnglishLe Morte d'ArthurbySir Thomas Malory(c.1408–1471) was written in prose, and the work dominates the Arthurian literature.[16]Arthurian motifs have appeared steadily in literature from its publication, though the works have been a mix of fantasy and non-fantasy works.[17]At the time, it and the SpanishAmadis de Gaula(1508), which was also written in prose, spawned many imitators, and the genre was popularly well-received. It later produced such masterpieces of Renaissance poetry asLudovico Ariosto'sOrlando furiosoandTorquato Tasso'sGerusalemme Liberata.Ariosto's tale in particular was a source text for many fantasies of adventure.[18]

During theRenaissance,Giovanni Francesco Straparolawrote and publishedThe Facetious Nights of Straparola(1550–1555), a collection of stories of which many are literaryfairy tales.Giambattista Basilewrote and published thePentamerone,which was the first collection of stories to contain solely what would later be known as fairy tales. The two works include the oldest recorded form of many well-known (and some more obscure) European fairy tales.[19]This was the beginning of a tradition that would both influence the fantasy genre and be incorporated in it, as many works offairytale fantasyappear to this day.[20]

In a work onalchemyin the 16th century,Paracelsus(1493–1541) identified four types of beings with the four elements of alchemy:gnomes(earth elementals);undines(water);sylphs(air); andsalamanders(fire).[21]Most of these beings are found in folklore as well as alchemy, and their names are often used interchangeably with similar beings from folklore.[22]

Enlightenment[edit]

Literary fairy tales, such as those written byCharles Perrault(1628–1703) andMadame d'Aulnoy(c.1650 – 1705), became very popular early in theAge of Enlightenment.Many of Perrault's tales became fairy tale staples and were influential to later fantasy. When d'Aulnoy termed her workscontes de fée(fairy tales), she invented the term that is now generally used for the genre, thus distinguishing such tales from those involving no marvels.[23]This approach influenced later writers who took up the folk fairy tales in the same manner during theRomantic era.[24]

Several fantasies aimed at an adult readership were also published in 18th century France, includingVoltaire's "contes philosophique"The Princess of Babylon(1768) andThe White Bull(1774).[25]This era, however, was notably hostile to fantasy. Writers of the new types of fiction such asDefoe,Richardson,andFieldingwere realistic in style, and many early realistic works were critical of fantastical elements in fiction.[26]

However, in theElizabethan erainEngland,fantasy literature became extraordinarily popular and fueledpopulistandanti-authoritariansentiment during the1590s.[27]Topics that were written about included "fairylandsin which the sexes traded places [and] men and immortals mingl[ing] ".[27]

Romanticism[edit]

Romanticism,a movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, was a dramatic reaction to rationalism, challenging the priority of reason and promoting the importance of imagination and spirituality. Its success in rehabilitating imagination was of fundamental importance to the evolution of fantasy, and its interest in medievalromancesprovided many motifs to modern fantasy.[28]

The Romantics invoked the medieval romance as a model for the works they wanted to produce, in contrast to the realism of the Enlightenment.[29]One of the first literary results of this trend was theGothic novel,a genre that began in Britain withThe Castle of Otranto(1764) byHorace Walpole.That work is considered the predecessor to both modern fantasy and modernhorror fiction.[24]Another noted Gothic novel which also contains a large amount ofArabian Nights-influenced fantasy elements isVathek(1786) byWilliam Thomas Beckford.[30]

In the later part of the Romantic period, folklorists collected folktales, epic poems, and ballads, and released them in printed form. TheBrothers Grimmwere inspired by the movement ofGerman Romanticismin their 1812 collectionGrimm's Fairy Tales,and they in turn inspired other collectors. Frequently their motivation stemmed not merely from Romanticism, but fromRomantic nationalism,in that many were inspired to save their own country's folklore. Sometimes, as in theKalevala,they compiled existing folklore into an epic to match other nation's, and sometimes, as inThe Poems of Ossian,they fabricated folklore that should have been there. These works, whether fairy tale, ballads, or folk epics, were a major source for later fantasy works.[31]

The Romantic interest in medievalism also resulted in a revival of interest in the literary fairy tale. The tradition begun withGiovanni Francesco StraparolaandGiambattista Basileand developed byCharles Perraultand the Frenchprécieuseswas taken up by the German Romantic movement. The German authorFriedrich de la Motte Fouquécreated medieval-set stories such asUndine(1811) andSintram and his Companions(1815), which would later inspire British writers such asGeorge MacDonaldandWilliam Morris.[32][33][34] E.T.A. Hoffmann's tales, such asThe Golden Pot(1814) andThe Nutcracker and the Mouse King(1816) were notable additions to the canon of German fantasy.[35]Ludwig Tieck's collectionPhantasus(1812–1817) contained several short fairy tales, including "The Elves".[36]

In France, the main writers of Romantic-era fantasy wereCharles NodierwithSmarra(1821) andTrilby(1822)[37][38]andThéophile Gautierwho penned such stories as "Omphale" (1834) and "One of Cleopatra's Nights"(1838) as well as the novelSpirite(1866).[39][40]

Victorian era[edit]

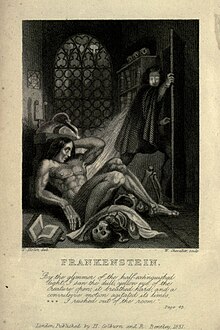

Fantasy literature was popular inVictorian times,with the works of writers such asMary Shelley,William Morris, George MacDonald, andCharles Dodgsonreaching wider audiences.

Hans Christian Andersentook a new approach to fairy tales by creating original stories told in a serious fashion.[41]From this origin,John RuskinwroteThe King of the Golden River(1851), a fairy tale that included complex levels of characterization and created in the Southwest Wind an irascible but kindly character similar toJ.R.R. Tolkien's laterGandalf.[41]

The history of modern fantasy literature began with George MacDonald, author of such novels asThe Princess and the Goblin(1868) andPhantastes(1868), the latter of which is widely considered to be the first fantasy novel written for adults. MacDonald also wrote one of the first critical essays about the fantasy genre, "The Fantastic Imagination", in his bookA Dish of Orts(1893).[42][43]MacDonald was a major influence on both Tolkien andC. S. Lewis.[44]

The other major fantasy author of this era was William Morris, an admirer of theMiddle Agesand a poet who wrote several fantastic romances and novels in the latter part of the 19th century, includingThe Well at the World's End(1896). Morris was inspired by the medieval sagas, and his writing was deliberately archaic in the style of thechivalric romances.[45]Morris's work represented an important milestone in the history of fantasy, as while other writers wrote of foreign lands or ofdream worlds,Morris was the first to set his stories in an entirelyinvented world.[46]

Authors such asEdgar Allan PoeandOscar Wildealso contributed to the development of fantasy with their writing of horror stories.[47]Wilde also wrote a large number of children's fantasies, collected inThe Happy Prince and Other Stories(1888) andA House of Pomegranates(1891).[48]H. Rider Haggarddeveloped the conventions of thelost worldsubgenre with his novelKing Solomon's Mines(1885), which presented a fantastical Africa to a European audience still unfamiliar with the continent.[49]Other writers, includingEdgar Rice BurroughsandAbraham Merritt,further developed the style.

Several classicchildren's fantasiessuch asLewis Carroll'sAlice's Adventures in Wonderland(1865),[50]L. Frank Baum'sThe Wonderful Wizard of Oz(1900), as well as the work ofE. NesbitandFrank R. Stocktonwere also published around this time.[51]C. S. Lewisnoted that in the earlier part of the 20th century, fantasy was more accepted in juvenile literature, and therefore a writer interested in fantasy often wrote for that audience, despite using concepts and themes that could form a work aimed at adults.[52]

At this time, the terminology for the genre was not settled. Many fantasies in this era were termed fairy tales, includingMax Beerbohm's "The Happy Hypocrite"(1896) and MacDonald'sPhantastes.[53]It was not until 1923 that the term "fantasist" was used to describe a writer (in this case, Oscar Wilde) who wrote fantasy fiction.[54]The name "fantasy" was not developed until later; as late as J.R.R. Tolkien'sThe Hobbit(1937), the term "fairy tale" was still being used.

After 1901[edit]

An important factor in the development of the fantasy genre was the arrival of magazines devoted to fantasy fiction. The first such publication was the German magazineDer Orchideengartenwhich ran from 1919 to 1921.[55]In 1923, the first English-language fantasy fiction magazine,Weird Tales,was created.[56]Many other similar magazines eventually followed.[57]andThe Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction[58]

H. P. Lovecraftwas deeply influenced by Edgar Allan Poe and to a somewhat lesser extent, by Lord Dunsany; with hisCthulhu Mythosstories, he became one of the most influential writers of fantasy and horror in the 20th century.[59]

Despite MacDonald's future influence, and Morris' popularity at the time, it was not until around the start of the 20th century that fantasy fiction began to reach a large audience, with authors such asLord Dunsany(1878–1957) who, following Morris's example, wrote fantasy novels, but also in the short story form.[45]He was particularly noted for his vivid and evocative style.[45]His style greatly influenced many writers, not always happily;Ursula K. Le Guin,in her essay on style in fantasy "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie", wryly referred to Lord Dunsany as the "First Terrible Fate that Awaiteth Unwary Beginners in Fantasy", alluding to young writers attempting to write in Lord Dunsany's style.[60]According toS. T. Joshi,"Dunsany's work had the effect of segregating fantasy—a mode whereby the author creates his own realm of pure imagination—from supernatural horror. From the foundations he established came the later work ofE. R. Eddison,Mervyn Peake,and J. R. R. Tolkien.[61]

In Britain in the aftermath of World War I, a notably large number of fantasy books aimed at an adult readership were published, includingLiving Alone(1919) byStella Benson,[62]A Voyage to Arcturus(1920) byDavid Lindsay,[63]Lady into Fox(1922) byDavid Garnett,[62]Lud-in-the-Mist(1926) byHope Mirrlees,[62][64]andLolly Willowes(1926) bySylvia Townsend Warner.[62][65]E. R. Eddisonwas another influential writer who wrote during this era. He drew inspiration from Northern sagas, as Morris did, but his prose style was modeled more on Tudor and Elizabethan English, and his stories were filled with vigorous characters in glorious adventures.[46]Eddison's most famous work isThe Worm Ouroboros(1922), a long heroic fantasy set on an imaginary version of the planet Mercury.[66]

Literary critics of the era began to take an interest in "fantasy" as a genre of writing, and also to argue that it was a genre worthy of serious consideration.Herbert Readdevoted a chapter of his bookEnglish Prose Style(1928) to discussing "Fantasy" as an aspect of literature, arguing it was unjustly considered suitable only for children: "The Western World does not seem to have conceived the necessity of Fairy Tales for Grown-Ups".[43]

In 1938, with the publication ofThe Sword in the Stone,T. H. Whiteintroduced one of the most notable works ofcomic fantasy.[67]

The first major contribution to the genre after World War II wasMervyn Peake'sTitus Groan(1946), the book that launched theGormenghast series.J. R. R. Tolkienplayed a large role in the popularization and accessibility of the fantasy genre with his highly successful publicationsThe Hobbit(1937) andThe Lord of the Rings(1954–55).[68]Tolkien was largely influenced by an ancient body ofAnglo-Saxon myths,particularlyBeowulf,as well as William Morris's romances andE. R. Eddison's 1922 novel,The Worm Ouroboros.Tolkien's close friendC. S. Lewis,author ofThe Chronicles of Narnia(1950–56) and a fellow English professor with a similar array of interests, also helped to publicize the fantasy genre.Tove Jansson,author ofThe Moomins,was also a strong contributor to the popularity of fantasy literature in the field of children and adults.[69]

The tradition established by these predecessors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has continued to thrive and be adapted by new authors. Theinfluence of J.R.R. Tolkien's fictionhas—particularly over the genre ofhigh fantasy—prompted a reaction.[70]

In China, the idea of fantasy literature as a distinct genre first became prevalent in the early 21st century.[71]: 42 China has long had pre-genre stories with fantastical elements, includingzhiguai,ghost stories, and miracle tales, among others.[71]: 42

It is not uncommon for fantasy novels to be ranked onThe New York TimesBest Seller list,and some have been at number one on the list, including most recently,Brandon Sandersonin 2014,[72]Neil Gaimanin 2013,[73]Patrick Rothfuss[74]andGeorge R. R. Martinin 2011,[75]andTerry Goodkindin 2006.[76]

Style[edit]

Symbolism often plays a significant role in fantasy literature, often through the use of archetypal figures inspired by earlier texts orfolklore.Some argue that fantasy literature and its archetypes fulfill a function for individuals and society and the messages are continually updated for current societies.[77]

Ursula K. Le Guin,in her essay "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie", presented the idea that language is the most crucial element ofhigh fantasy,because it creates a sense of place. She analyzed the misuse of a formal, "olden-day" style, saying that it was a dangerous trap for fantasy writers because it was ridiculous when done wrong. She warns writers away from trying to base their style on that of masters such asLord DunsanyandE. R. Eddison,[78]emphasizing that language that is too bland or simplistic creates the impression that the fantasy setting is simply a modern world in disguise, and presents examples of clear, effective fantasy writing in brief excerpts fromTolkienandEvangeline Walton.[79]

Michael Moorcockobserved that many writers use archaic language for its sonority and to lend color to a lifeless story.[31]Brian Peters writes that in various forms offairytale fantasy,even the villain's language might be inappropriate if vulgar.[80]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Taproot texts", p 921ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^Prickett, Stephen (1979).Victorian Fantasy.Indiana University Press. p. 229.ISBN0-253-17461-9.

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Elemental" p 313-4,ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^Jacobs 1888,Introduction, page xv;Ryder 1925,Translator's introduction, quoting Hertel: "the original work was composed in Kashmir, about 200 B.C. At this date, however, many of the individual stories were already ancient."

- ^Doris Lessing,Problems, Myths and StoriesArchived2016-05-09 at theWayback Machine,London: Institute for Cultural Research Monograph Series No. 36, 1999, p 13

- ^Richard Matthews (2002).Fantasy: The Liberation of Imagination,p. 8-10.Routledge.ISBN0-415-93890-2.

- ^Isabel Burton,PrefaceArchived21 May 2017 at theWayback Machine,inRichard Francis Burton(1870),Vikram and The Vampire.

- ^L. Sprague de Camp,Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers:The Makers of Heroic Fantasy,p 10ISBN0-87054-076-9

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Arabian fantasy", p 52ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Nordic fantasy", p 692ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Beowulf", p 107ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^abcJohn Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Celtic fantasy", p 275ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^Michael Moorcock,Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasyp 101ISBN1-932265-07-4

- ^Colin Manlove,Christian Fantasy: from 1200 to the Presentp 12ISBN0-268-00790-X

- ^Lewis, C. S.(1994).The Discarded Image.Cambridge University Press. p. 9.ISBN0-521-47735-2.

- ^John GrantandJohn Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Malory, (Sir) Thomas" p 621,ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Arthur" p 60-1,ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Ariosto, Lodovico" p 60-1,ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^Steven Swann Jones,The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination,Twayne Publishers, New York, 1995,ISBN0-8057-0950-9,p38

- ^L. Sprague de Camp,Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy,p 11ISBN0-87054-076-9

- ^Carole B. Silver,Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness,p 38ISBN0-19-512199-6

- ^C.S. Lewis,The Discarded Image,p135ISBN0-521-47735-2

- ^Jack Zipes,The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm,p 858,ISBN0-393-97636-X

- ^abL. Sprague de Camp,Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers:The Makers of Heroic Fantasy,p 9-11ISBN0-87054-076-9

- ^Brian Stableford,The A to Z of Fantasy Literature,p xx, Scarecrow Press, Plymouth. 2005.ISBN0-8108-6829-6

- ^Lin Carter,ed.Realms of Wizardryp xiii–xiv Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^abSchama, Simon(2003).A History of Britain 1: 3000 BC-AD 1603 At the Edge of the World?(Paperback 2003 ed.). London:BBC Worldwide.p. 390.ISBN978-0-563-48714-2.

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Romanticism", p 821ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^John Grant and John Clute,The Encyclopedia of Fantasy,"Romance", p 821ISBN0-312-19869-8

- ^Brian Stableford,The A to Z of Fantasy Literature,p 40, Scarecrow Press, Plymouth. 2005.ISBN0-8108-6829-6

- ^abMichael Moorcock,Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasyp 35ISBN1-932265-07-4

- ^ Brian Stableford,"Undine", (pp. 1992–1994). inFrank N. Magill,ed.Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature,Vol 4. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Salem Press, Inc., 1983.ISBN0-89356-450-8

- ^Mike Ashley, "Fouqué, Friedrich (Heinrich Karl),(Baron) de la Motte",(p. 654-5) inSt. James Guide To Fantasy Writers,edited byDavid Pringle.St. James Press, 1996.ISBN1-55862-205-5

- ^Veronica Ortenberg,In Search of the Holy Grail: The Quest for the Middle Ages, (38–9) Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006,ISBN1-85285-383-2.

- ^Penrith Goff, "E.T.A. Hoffmann", (pp.111–120) in E. F. Bleiler,Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror.New York: Scribner's, 1985.ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^D. P Haase, "Ludwig Tieck" (pp.83–90), in E. F. Bleiler,Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror.New York: Scribner's, 1985.ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^Franz Rottensteiner,The Fantasy Book:an illustrated history from Dracula to Tolkien(p. 137) Collier Books, 1978.ISBN0-02-053560-0

- ^A. Richard Oliver,Charles Nodier:Pilot of Romanticism.(p. 134-37) Syracuse University Press, 1964.

- ^Brian Stableford,The A to Z of Fantasy Literature(p. 159), Scarecrow Press, Plymouth. 2005.ISBN0-8108-6829-6

- ^Brian Stableford, "Théophile Gautier", (pp. 45–50) in E. F. Bleiler,Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror.New York: Scribner's, 1985.ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^abPrickett, Stephen (1979).Victorian Fantasy.Indiana University Press. pp. 66–67.ISBN0-253-17461-9.

- ^George MacDonald, "The Fantastic Imagination". Reprinted in Boyer, Robert H. and Zahorski, Kenneth J.Fantasists on Fantasy.New York: Avon Discus, 1984. pp. 11–22,ISBN0-380-86553-X

- ^abScholes, Robert(1987). "Boiling Roses". In Slusser, George E.; Rabkin, Eric S. (eds.).Intersections: Fantasy and Science Fiction.Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 3–18.ISBN080931374X.

- ^Gary K. Wolfe,"George MacDonald", pp. 239–246 in Bleiler, E. F., ed.Supernatural Fiction Writers.New York: Scribner's, 1985.ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^abcLin Carter, ed.Realms of Wizardryp 2 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^abLin Carter, ed.Kingdoms of Sorcery,p 39 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^Stephen Prickett,Victorian Fantasyp 98-9ISBN0-253-17461-9

- ^M. J. Elkins, "Oscar Wilde" in E. F. Bleiler, ed.Supernatural Fiction Writers.New York: Scribner's, 1985. (pp.345–350).ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^Lin Carter, ed.Realms of Wizardryp 64 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^J.R. Pfeiffer,"Lewis Carroll", p 247-54, inE. F. Bleiler,Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror.Scribner's, New York, 1985ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^Brian Stableford,The A to Z of Fantasy Literature,p 70-3, Scarecrow Press, Plymouth. 2005.ISBN0-8108-6829-6

- ^C. S. Lewis, "On Juvenile Tastes", p 41,Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories,ISBN0-15-667897-7

- ^W.R. Irwin,The Game of the Impossible,p 92-3, University of Illinois Press, Urbana Chicago London, 1976

- ^The term was referenced in a supplement to theOxford English Dictionary.See Michael W. McClintock, "High Tech and High Sorcery: Some Discriminations Between Science Fiction and Fantasy", in George E. Slusser, and Eric S. Rabkin, ed.,Intersections: Fantasy and Science Fiction.Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1987.ISBN080931374X(pp.26–35.).

- ^"Orchideengarten, Der". in: M.B. Tymn andMike Ashley,Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines.Westport: Greenwood, 1985. pp. 866. ISBN0-313-21221-X

- ^Robert Weinberg,The Weird Tales Story,Wildside Press, 1999.ISBN1-58715-101-4

- ^"Unknown". in: M.B. Tymn and Mike Ashley,Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines.Westport: Greenwood, 1985. pp. 694–698.ISBN0-313-21221-X

- ^Thomas D. Clareson, "Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction" in M.B. Tymn and Mike Ashley,Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines.Westport: Greenwood, 1985. (pp. 377–391).ISBN0-313-21221-X

- ^L. Sprague de Camp,Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy,p. 79ISBN0-87054-076-9

- ^Ursula K. Le Guin, "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie", pp. 78–79The Language of the NightISBN0-425-05205-2

- ^Olson, Danel (29 December 2010).21st-Century Gothic: Great Gothic Novels Since 2000.Scarecrow Press.ISBN9780810877290.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2023.Retrieved15 March2023.

- ^abcdBrian Stableford, "Re-Enchantment in the Aftermath of War", in Stableford,Gothic Grotesques: Essays on Fantastic Literature.Wildside Press, 2009,ISBN978-1-4344-0339-1

- ^"David Lindsay" by Gary K. Wolfe, (pp. 541–548) in E. F. Bleiler, ed.Supernatural Fiction Writers.New York: Scribner's, 1985.ISBN0-684-17808-7

- ^E.L. Chapman, "Lud-in-the-Mist", in Frank N. Magill, ed.Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature,Vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Salem Press, Inc., 1983.ISBN0-89356-450-8.pp. 926–931.

- ^Robin Anne Reid,Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy(p.39), ABC-CLIO, 2009ISBN0313335915.

- ^Michael Moorcock,Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasyp 47ISBN1-932265-07-4

- ^Lin Carter, ed.Kingdoms of Sorcery,p 121-2 Doubleday and Company Garden City, NY, 1976

- ^Sirangelo Maggio, Sandra; Fritsch, Valter Henrique (2011)."There and Back Again: Tolkien'sThe Lord of the Ringsin the Modern Fiction ".Recorte: Revista Eletrônica.8(2).Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.Retrieved7 July2012.

- ^"Tove Jansson: Love, war and the Moomins | BBC News".BBC News.13 March 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2017.Retrieved28 April2020.

- ^Fornet-Ponse, Thomas. Tolkien's Influence on Fantasy: Interdisziplinäres Seminar Der DTG 27. Bis 29. April 2012, Jena = Tolkiens Einfluss Auf Die Moderne Fantasy. Vol. 9. Düsseldorf: Scriptorium Oxoniae., n.d. Print.

- ^abReinders, Eric (2024).Reading Tolkien in Chinese: Religion, Fantasy, and Translation.Perspectives on Fantasy series. London, UK:BloomsburyAcademic.ISBN9781350374645.

- ^Brandon Sanderson tops best sellers list with Words of RadianceArchived18 August 2017 at theWayback MachineApril 17, 2014

- ^"Best-Seller Lists: Hardcover Fiction".The New York Times.7 July 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2013.Retrieved15 August2013.

- ^"' 'The New York Times ' ' Best Seller list: March 20, 2011 "(PDF).Hawes.Archived(PDF)from the original on 5 October 2011.Retrieved16 November2011.

- ^"New York Times bestseller list".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.Retrieved24 July2011.

- ^"Hawes' archive ofNew York Timesbestsellers — Week of January 23, 2005 "(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 3 April 2018.Retrieved6 April2011.

- ^"Indick, William. Ancient Symbology in Fantasy Literature: A Psychological Study. Jefferson: McFarland &, 2012. Print".Archived fromthe originalon 29 June 2013.Retrieved4 April2013.

- ^Ursula K. Le Guin, "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie", p 74-5The Language of the NightISBN0-425-05205-2

- ^Ursula K. Le Guin, "From Elfland to Poughkeepsie", pp. 78–80The Language of the NightISBN0-425-05205-2

- ^Alec Austin,"Quality in Epic Fantasy"Archived2014-08-08 at theWayback Machine.The generic features of historical fantasy literature, as a mode of inverting the real (including nineteenth-century ghost stories, children's stories, city comedies, classical dreams, stories of highway women, and Edens) are discussed inWriting and Fantasy,ed. Ceri Sullivan and Barbara White (London: Longman, 1999)

Works cited[edit]

- Jacobs, Joseph (1888),The earliest English version of the Fables of Bidpai,London

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ryder, Arthur W. (transl)(1925),The Panchatantra,University of Chicago Press,ISBN81-7224-080-5