Fatigue (material)

It has been suggested thatStatic fatiguebemergedinto this article. (Discuss)Proposed since August 2024. |

| Mechanical failure modes |

|---|

Inmaterials science,fatigueis the initiation and propagation of cracks in a material due to cyclic loading. Once afatigue crackhas initiated, it grows a small amount with each loading cycle, typically producingstriationson some parts of the fracture surface. The crack will continue to grow until it reaches a critical size, which occurs when thestress intensity factorof the crack exceeds thefracture toughnessof the material, producing rapid propagation and typically complete fracture of the structure.

Fatigue has traditionally been associated with the failure of metal components which led to the termmetal fatigue.In the nineteenth century, the sudden failing of metal railway axles was thought to be caused by the metalcrystallisingbecause of the brittle appearance of the fracture surface, but this has since been disproved.[1]Most materials, such as composites, plastics and ceramics, seem to experience some sort of fatigue-related failure.[2]

To aid in predicting the fatigue life of a component,fatigue testsare carried out using coupons to measure the rate of crack growth by applying constant amplitude cyclic loading and averaging the measured growth of a crack over thousands of cycles. However, there are also a number of special cases that need to be considered where the rate of crack growth is significantly different compared to that obtained from constant amplitude testing, such as the reduced rate of growth that occurs for small loads near thethresholdor after the application of anoverload,and the increased rate of crack growth associated withshort cracksor after the application of anunderload.[2]

If the loads are above a certain threshold, microscopic cracks will begin toinitiateatstress concentrationssuch as holes,persistent slip bands(PSBs),compositeinterfaces orgrain boundariesin metals.[3]Thestressvalues that cause fatigue damage are typically much less than theyield strengthof the material.

Stages of fatigue

[edit]Historically, fatigue has been separated into regions ofhigh cycle fatiguethat require more than 104cycles to failure where stress is low and primarilyelasticandlow cycle fatiguewhere there is significant plasticity. Experiments have shown that low cycle fatigue is also crack growth.[4]

Fatigue failures, both for high and low cycles, all follow the same basic steps: crack initiation, crack growth stages I and II, and finally ultimate failure. To begin the process, cracks must nucleate within a material. This process can occur either atstress risersin metallic samples or at areas with a high void density in polymer samples. These cracks propagate slowly at first duringstage Icrack growth along crystallographic planes, whereshear stressesare highest. Once the cracks reach a critical size they propagate quickly duringstage IIcrack growth in a direction perpendicular to the applied force. These cracks can eventually lead to the ultimate failure of the material, often in a brittle catastrophic fashion.

Crack initiation

[edit]The formation of initial cracks preceding fatigue failure is a separate process consisting of four discrete steps in metallic samples. The material will develop cell structures and harden in response to the applied load. This causes the amplitude of the applied stress to increase given the new restraints on strain. These newly formed cell structures will eventually break down with the formation of persistent slip bands (PSBs). Slip in the material is localized at these PSBs, and the exaggerated slip can now serve as a stress concentrator for a crack to form. Nucleation and growth of a crack to a detectable size accounts for most of the cracking process. It is for this reason that cyclic fatigue failures seem to occur so suddenly where the bulk of the changes in the material are not visible without destructive testing. Even in normally ductile materials, fatigue failures will resemble sudden brittle failures.

PSB-induced slip planes result in intrusions and extrusions along the surface of a material, often occurring in pairs.[5]This slip is not amicrostructuralchange within the material, but rather a propagation ofdislocationswithin the material. Instead of a smooth interface, the intrusions and extrusions will cause the surface of the material to resemble the edge of a deck of cards, where not all cards are perfectly aligned. Slip-induced intrusions and extrusions create extremely fine surface structures on the material. With surface structure size inversely related to stress concentration factors, PSB-induced surface slip can cause fractures to initiate.

These steps can also be bypassed entirely if the cracks form at a pre-existing stress concentrator such as from an inclusion in the material or from a geometric stress concentrator caused by a sharp internal corner or fillet.

Crack growth

[edit]Most of the fatigue life is generally consumed in the crack growth phase. The rate of growth is primarily driven by the range of cyclic loading although additional factors such as mean stress, environment, overloads and underloads can also affect the rate of growth. Crack growth may stop if the loads are small enough to fall below a critical threshold.

Fatigue cracks can grow from material or manufacturing defects from as small as 10 μm.

When the rate of growth becomes large enough, fatigue striations can be seen on the fracture surface. Striations mark the position of the crack tip and the width of each striation represents the growth from one loading cycle. Striations are a result of plasticity at the crack tip.

When the stress intensity exceeds a critical value known as the fracture toughness, unsustainablefast fracturewill occur, usually by a process ofmicrovoid coalescence.Prior to final fracture, the fracture surface may contain a mixture of areas of fatigue and fast fracture.

Acceleration and retardation

[edit]The following effects change the rate of growth:[2]

- Mean stress effect: Higher mean stress increases the rate of crack growth.

- Environment: Increased moisture increases the rate of crack growth. In the case of aluminium, cracks generally grow from the surface, where water vapour from the atmosphere is able to reach the tip of the crack and dissociate into atomic hydrogen which causeshydrogen embrittlement.Cracks growing internally are isolated from the atmosphere and grow in avacuumwhere the rate of growth is typically an order of magnitude slower than a surface crack.[6]

- Short crack effect: In 1975, Pearson observed that short cracks grow faster than expected.[7]Possible reasons for the short crack effect include the presence of the T-stress, the tri-axial stress state at the crack tip, the lack of crack closure associated with short cracks and the large plastic zone in comparison to the crack length. In addition, long cracks typically experience a threshold which short cracks do not have.[8]There are a number of criteria for short cracks:[9]

- cracks are typically smaller than 1 mm,

- cracks are smaller than the material microstructure size such as the grain size, or

- crack length is small compared to the plastic zone.

- Underloads: Small numbers of underloads increase the rate of growth and may counteract the effect of overloads.

- Overloads: Initially overloads (> 1.5 the maximum load in a sequence) lead to a small increase in the rate of growth followed by a long reduction in the rate of growth.

Characteristics of fatigue

[edit]- In metal alloys, and for the simplifying case when there are no macroscopic or microscopic discontinuities, the process starts with dislocation movements at the microscopic level, which eventually form persistent slip bands that become the nucleus of short cracks.

- Macroscopic and microscopic discontinuities (at the crystalline grain scale) as well as component design features which cause stress concentrations (holes,keyways,sharp changes of load direction etc.) are common locations at which the fatigue process begins.

- Fatigue is a process that has a degree of randomness (stochastic), often showing considerable scatter even in seemingly identical samples in well controlled environments.

- Fatigue is usually associated with tensile stresses but fatigue cracks have been reported due to compressive loads.[10]

- The greater the applied stress range, the shorter the life.

- Fatigue life scatter tends to increase for longer fatigue lives.

- Damage is irreversible. Materials do not recover when rested.

- Fatigue life is influenced by a variety of factors, such astemperature,surface finish,metallurgical microstructure, presence ofoxidizingorinertchemicals,residual stresses,scuffing contact (fretting), etc.

- Some materials (e.g., somesteelandtitaniumalloys) exhibit a theoreticalfatigue limitbelow which continued loading does not lead to fatigue failure.

- High cyclefatigue strength(about 104to 108cycles) can be described by stress-based parameters. A load-controlled servo-hydraulic test rig is commonly used in these tests, with frequencies of around 20–50 Hz. Other sorts of machines—like resonant magnetic machines—can also be used, to achieve frequencies up to 250 Hz.

- Low-cycle fatigue(loading that typically causes failure in less than 104cycles) is associated with localized plastic behavior in metals; thus, a strain-based parameter should be used for fatigue life prediction in metals. Testing is conducted with constant strain amplitudes typically at 0.01–5 Hz.

Timeline of research history

[edit]

- 1837:Wilhelm Albertpublishes the first article on fatigue. He devised a test machine forconveyorchains used in theClausthalmines.[11]

- 1839:Jean-Victor Ponceletdescribes metals as being 'tired' in his lectures at the military school atMetz.

- 1842:William John Macquorn Rankinerecognises the importance ofstress concentrationsin his investigation ofrailroadaxlefailures. TheVersailles train wreckwas caused by fatigue failure of a locomotive axle.[12]

- 1843:Joseph Glynnreports on the fatigue of an axle on a locomotive tender. He identifies thekeywayas the crack origin.

- 1848: TheRailway Inspectoratereports one of the first tyre failures, probably from a rivet hole in tread of railway carriage wheel. It was likely a fatigue failure.

- 1849:Eaton Hodgkinsonis granted a "small sum of money" to report to theUK Parliamenton his work in "ascertaining by direct experiment, the effects of continued changes of load upon iron structures and to what extent they could be loaded without danger to their ultimate security".

- 1854: F. Braithwaite reports on common service fatigue failures and coins the termfatigue.[13]

- 1860: Systematic fatigue testing undertaken by SirWilliam FairbairnandAugust Wöhler.

- 1870:A. Wöhlersummarises his work on railroad axles. He concludes that cyclic stress range is more important than peak stress and introduces the concept ofendurance limit.[11]

- 1903: SirJames Alfred Ewingdemonstrates the origin of fatigue failure in microscopic cracks.

- 1910: O. H. Basquin proposes a log-log relationship for S-N curves, using Wöhler's test data.[14]

- 1940:Sidney M. Cadwellpublishes first rigorous study of fatigue in rubber.[15]

- 1945: A. M. Miner popularises Palmgren's (1924) linear damage hypothesis as a practical design tool.[16][17]

- 1952:W. WeibullAn S-N curve model.[18]

- 1954: The world's first commercial jetliner, thede Havilland Comet,suffers disaster as three planes break up in mid-air, causing de Havilland and all other manufacturers to redesign high altitude aircraft and in particular replace square apertures like windows with oval ones.

- 1954: L. F. Coffin and S. S. Manson explain fatigue crack-growth in terms ofplasticstrainin the tip of cracks.

- 1961:P. C. Parisproposes methods for predicting the rate of growth of individual fatigue cracks in the face of initial scepticism and popular defence of Miner's phenomenological approach.

- 1968:Tatsuo Endoand M. Matsuishi devise therainflow-counting algorithmand enable the reliable application of Miner's rule torandomloadings.[19]

- 1970: Smith, Watson, and Topper developed a mean stress correction model, where the fatigue damage in a cycle is determined by the product of the maximum stress and strain amplitude.[20]

- 1970: W. Elber elucidates the mechanisms and importance ofcrack closurein slowing the growth of a fatigue crack due to the wedging effect ofplastic deformationleft behind the tip of the crack.[21][22]

- 1973: M. W. Brown and K. J. Miller observe that fatigue life under multiaxial conditions is governed by the experience of the plane receiving the most damage, and that both tension and shear loads on thecritical planemust be considered.[23]

Predicting fatigue life

[edit]

TheAmerican Society for Testing and Materialsdefinesfatigue life,Nf,as the number of stress cycles of a specified character that a specimen sustains beforefailureof a specified nature occurs.[24]For some materials, notablysteelandtitanium,there is a theoretical value for stress amplitude below which the material will not fail for any number of cycles, called afatigue limit or endurance limit.[25]However, in practice, several bodies of work done at greater numbers of cycles suggest that fatigue limits do not exist for any metals.[26][27][28]

Engineers have used a number of methods to determine the fatigue life of a material:[29]

- the stress-life method,

- the strain-life method,

- the crack growth method and

- probabilistic methods, which can be based on either life or crack growth methods.

Whether using stress/strain-life approach or using crack growth approach, complex or variable amplitude loading is reduced to a series of fatigue equivalent simple cyclic loadings using a technique such as therainflow-counting algorithm.

Stress-life and strain-life methods

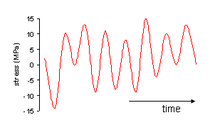

[edit]A mechanical part is often exposed to a complex, oftenrandom,sequence of loads, large and small. In order to assess the safe life of such a part using the fatigue damage or stress/strain-life methods the following series of steps is usually performed:

- Complex loading is reduced to a series of simple cyclic loadings using a technique such asrainflow analysis;

- Ahistogramof cyclic stress is created from the rainflow analysis to form afatigue damage spectrum;

- For each stress level, the degree of cumulative damage is calculated from the S-N curve; and

- The effect of the individual contributions are combined using an algorithm such asMiner's rule.

Since S-N curves are typically generated foruniaxialloading, some equivalence rule is needed whenever the loading is multiaxial. For simple, proportional loading histories (lateral load in a constant ratio with the axial),Sines rulemay be applied. For more complex situations, such as non-proportional loading,critical plane analysismust be applied.

Miner's rule

[edit]In 1945, Milton A. Miner popularised a rule that had first been proposed byArvid Palmgrenin 1924.[16]The rule, variously calledMiner's ruleor thePalmgren–Miner linear damage hypothesis,states that where there arekdifferent stress magnitudes in a spectrum,Si(1 ≤i≤k), each contributingni(Si) cycles, then ifNi(Si) is the number of cycles to failure of a constant stress reversalSi(determined by uni-axial fatigue tests), failure occurs when:

Usually, for design purposes, C is assumed to be 1. This can be thought of as assessing what proportion of life is consumed by a linear combination of stress reversals at varying magnitudes.

Although Miner's rule may be a useful approximation in many circumstances, it has several major limitations:

- It fails to recognize the probabilistic nature of fatigue and there is no simple way to relate life predicted by the rule with the characteristics of a probability distribution. Industry analysts often use design curves, adjusted to account for scatter, to calculateNi(Si).

- The sequence in which high vs. low stress cycles are applied to a sample in fact affect the fatigue life, for which Miner's Rule does not account. In some circumstances, cycles of low stress followed by high stress cause more damage than would be predicted by the rule.[30]It does not consider the effect of an overload or high stress which may result in a compressive residual stress that may retard crack growth. High stress followed by low stress may have less damage due to the presence of compressive residual stress (or localized plastic damages around crack tip).

Stress-life (S-N) method

[edit]

Materials fatigue performance is commonly characterized by anS-N curve,also known as aWöhlercurve.This is often plotted with the cyclic stress (S) against the cycles to failure (N) on alogarithmic scale.[31]S-N curves are derived from tests on samples of the material to be characterized (often called coupons or specimens) where a regularsinusoidalstress is applied by a testing machine which also counts the number of cycles to failure. This process is sometimes known ascoupon testing.For greater accuracy but lower generality component testing is used.[32]Each coupon or component test generates a point on the plot though in some cases there is arunoutwhere the time to failure exceeds that available for the test (seecensoring). Analysis of fatigue data requires techniques fromstatistics,especially survival analysis andlinear regression.

The progression of theS-N curvecan be influenced by many factors such as stress ratio (mean stress),[33]loading frequency,temperature,corrosion,residual stresses, and the presence of notches. A constant fatigue life (CFL) diagram[34]is useful for the study of stress ratio effect. TheGoodman lineis a method used to estimate the influence of the mean stress on thefatigue strength.

A Constant Fatigue Life (CFL) diagram is useful for stress ratio effect on S-N curve.[35]Also, in the presence of a steady stress superimposed on the cyclic loading, the Goodman relation can be used to estimate a failure condition. It plots stress amplitude against mean stress with the fatigue limit and theultimate tensile strengthof the material as the two extremes. Alternative failure criteria include Soderberg and Gerber.[36]

As coupons sampled from a homogeneous frame will display a variation in their number of cycles to failure, the S-N curve should more properly be a Stress-Cycle-Probability (S-N-P) curve to capture the probability of failure after a given number of cycles of a certain stress.

With body-centered cubic materials (bcc), the Wöhler curve often becomes a horizontal line with decreasing stress amplitude, i.e. there is afatigue strengththat can be assigned to these materials. With face-centered cubic metals (fcc), the Wöhler curve generally drops continuously, so that only afatigue limitcan be assigned to these materials.[37]

Strain-life (ε-N) method

[edit]

When strains are no longer elastic, such as in the presence of stress concentrations, the total strain can be used instead of stress as a similitude parameter. This is known as the strain-life method. The total strain amplitudeis the sum of the elastic strain amplitudeand the plastic strain amplitudeand is given by[2][38]

- .

Basquin's equation for the elastic strain amplitude is

whereisYoung's modulus.

The relation for high cycle fatigue can be expressed using the elastic strain amplitude

whereis a parameter that scales with tensile strength obtained by fitting experimental data,is the number of cycles to failure andis the slope of the log-log curve again determined by curve fitting.

In 1954, Coffin and Manson proposed that the fatigue life of a component was related to the plastic strain amplitude using

- .

Combining the elastic and plastic portions gives the total strain amplitude accounting for both low and high cycle fatigue

- .

whereis the fatigue strength coefficient,is the fatigue strength exponent,is the fatigue ductility coefficient,is the fatigue ductility exponent, andis the number of cycles to failure (being the number of reversals to failure).

Crack growth methods

[edit]An estimate of the fatigue life of a component can be made using acrack growth equationby summing up the width of each increment of crack growth for each loading cycle. Safety or scatter factors are applied to the calculated life to account for any uncertainty and variability associated with fatigue. The rate of growth used in crack growth predictions is typically measured by applying thousands of constant amplitude cycles to a coupon and measuring the rate of growth from the change in compliance of the coupon or by measuring the growth of the crack on the surface of the coupon. Standard methods for measuring the rate of growth have been developed by ASTM International.[9]

Crack growth equations such as theParis–Erdoğan equationare used to predict the life of a component. They can be used to predict the growth of a crack from 10 um to failure. For normal manufacturing finishes this may cover most of the fatigue life of a component where growth can start from the first cycle.[4]The conditions at the crack tip of a component are usually related to the conditions of test coupon using a characterising parameter such as the stress intensity,J-integralorcrack tip opening displacement.All these techniques aim to match the crack tip conditions on the component to that of test coupons which give the rate of crack growth.

Additional models may be necessary to include retardation and acceleration effects associated with overloads or underloads in the loading sequence. In addition, small crack growth data may be needed to match the increased rate of growth seen with small cracks.[39]

Typically, a cycle counting technique such as rainflow-cycle counting is used to extract the cycles from a complex sequence. This technique, along with others, has been shown to work with crack growth methods.[40]

Crack growth methods have the advantage that they can predict the intermediate size of cracks. This information can be used to schedule inspections on a structure to ensure safety whereas strain/life methods only give a life until failure.

Dealing with fatigue

[edit]

Design

[edit]Dependable design against fatigue-failure requires thorough education and supervised experience instructural engineering,mechanical engineering,ormaterials science.There are at least five principal approaches to life assurance for mechanical parts that display increasing degrees of sophistication:[41]

- Design to keep stress below threshold offatigue limit(infinite lifetime concept);

- Fail-safe,graceful degradation,andfault-tolerant design:Instruct the user to replace parts when they fail. Design in such a way that there is nosingle point of failure,and so that when any one part completely fails, it does not lead tocatastrophic failureof the entire system.

- Safe-life design:Design (conservatively) for a fixed life after which the user is instructed to replace the part with a new one (a so-calledlifedpart, finite lifetime concept, or "safe-life" design practice);planned obsolescenceanddisposable productare variants that design for a fixed life after which the user is instructed to replace the entire device;

- Damage tolerance:Is an approach that ensures aircraft safety by assuming the presence of cracks or defects even in new aircraft. Crack growth calculations, periodic inspections and component repair or replacement can be used to ensure critical components that may contain cracks, remain safe. Inspections usually usenondestructive testingto limit or monitor the size of possible cracks and require anaccurateprediction of the rate of crack-growth between inspections. The designer sets someaircraft maintenance checksschedule frequent enough that parts are replaced while the crack is still in the "slow growth" phase. This is often referred to as damage tolerant design or "retirement-for-cause".

- Risk Management:Ensures the probability of failure remains below an acceptable level. This approach is typically used for aircraft where acceptable levels may be based on probability of failure during a single flight or taken over the lifetime of an aircraft. A component is assumed to have a crack with a probability distribution of crack sizes. This approach can consider variability in values such as crack growth rates, usage and critical crack size.[42]It is also useful for considering damage at multiple locations that may interact to producemulti-siteorwidespread fatigue damage.Probability distributions that are common in data analysis and in design against fatigue include thelog-normal distribution,extreme value distribution,Birnbaum–Saunders distribution,andWeibull distribution.

Testing

[edit]Fatigue testingcan be used for components such as a coupon or afull-scale test articleto determine:

- the rate of crack growth and fatigue life of components such as a coupon or a full-scale test article.

- location of critical regions

- degree offail-safetywhen part of the structure fails

- the origin and cause of the crack initiating defect fromfractographicexamination of the crack.

These tests may form part of the certification process such as forairworthiness certification.

Repair

[edit]- Stop drillFatigue cracks that have begun to propagate can sometimes be stopped bydrillingholes, calleddrill stops,at the tip of the crack.[43]The possibility remains of a new crack starting in the side of the hole.

- Blend.Small cracks can be blended away and the surface cold worked or shot peened.

- Oversize holes.Holes with cracks growing from them can be drilled out to a larger hole to remove cracking and bushed to restore the original hole. Bushes can be cold shrinkInterference fitbushes to induce beneficial compressive residual stresses. The oversized hole can also be cold worked by drawing an oversized mandrel through the hole.[44]

- Patch.Cracks may be repaired by installing a patch or repair fitting. Composite patches have been used to restore the strength of aircraft wings after cracks have been detected or to lower the stress prior to cracking in order to improve the fatigue life.[45]Patches may restrict the ability to monitor fatigue cracks and may need to be removed and replaced for inspections.

Life improvement

[edit]

- Change material.Changes in the materials used in parts can also improve fatigue life. For example, parts can be made from better fatigue rated metals. Complete replacement and redesign of parts can also reduce if not eliminate fatigue problems. Thushelicopter rotorblades andpropellersin metal are being replaced bycompositeequivalents. They are not only lighter, but also much more resistant to fatigue. They are more expensive, but the extra cost is amply repaid by their greater integrity, since loss of a rotor blade usually leads to total loss of the aircraft. A similar argument has been made for replacement of metal fuselages, wings and tails of aircraft.[46]

- Induce residual stressesPeeninga surface can reduce such tensile stresses and create compressiveresidual stress,which prevents crack initiation. Forms of peening include:shot peening,using high-speed projectiles,high-frequency impact treatment(also called high-frequency mechanical impact) using a mechanical hammer,[47][48]andlaser peeningwhich uses high-energy laser pulses.Low plasticity burnishingcan also be used to induce compresses stress in fillets and cold work mandrels can be used for holes.[49]Increases in fatigue life and strength are proportionally related to the depth of the compressive residual stresses imparted. Shot peening imparts compressive residual stresses approximately 0.005 inches (0.1 mm) deep, while laser peening can go 0.040 to 0.100 inches (1 to 2.5 mm) deep, or deeper.[50][failed verification]

- Deep cryogenic treatment.The use of Deep Cryogenic treatment has been shown to increase resistance to fatigue failure. Springs used in industry, auto racing and firearms have been shown to last up to six times longer when treated. Heat checking, which is a form of thermal cyclic fatigue has been greatly delayed.[51]

- Re-profiling.Changing the shape of a stress concentration such as a hole or cutout may be used to extend the life of a component.Shape optimisationusing numerical optimisation algorithms have been used to lower the stress concentration in wings and increase their life.[52]

Fatigue of composites

[edit]Composite materialscan offer excellent resistance to fatigue loading. In general, composites exhibit goodfracture toughnessand, unlike metals, increase fracture toughness with increasing strength. The critical damage size in composites is also greater than that for metals.[53]

The primary mode of damage in a metal structure is cracking. For metal, cracks propagate in a relatively well-defined manner with respect to the applied stress, and the critical crack size and rate of crack propagation can be related to specimen data through analytical fracture mechanics. However, with composite structures, there is no single damage mode which dominates. Matrix cracking, delamination, debonding, voids, fiber fracture, and composite cracking can all occur separately and in combination, and the predominance of one or more is highly dependent on thelaminateorientations and loading conditions.[54]In addition, the unique joints and attachments used for composite structures often introduce modes offailuredifferent from those typified by the laminate itself.[55]

The composite damage propagates in a less regular manner and damage modes can change. Experience with composites indicates that the rate of damage propagation in does not exhibit the two distinct regions of initiation and propagation like metals. The crack initiation range in metals is propagation, and there is a significant quantitative difference in rate while the difference appears to be less apparent with composites.[54]Fatigue cracks of composites may form in thematrixand propagate slowly since the matrix carries such a small fraction of the appliedstress.And thefibersin the wake of the crack experience fatigue damage. In many cases, the damage rate is accelerated by deleterious interactions with the environment likeoxidationor corrosion of fibers.[56]

Notable fatigue failures

[edit]Versailles train crash

[edit]

Following theKing Louis-Philippe I's celebrations at thePalace of Versailles,a train returning to Paris crashed in May 1842 atMeudonafter the leading locomotive broke an axle. The carriages behind piled into the wrecked engines and caught fire. At least 55 passengers were killed trapped in the locked carriages, including the explorerJules Dumont d'Urville.This accident is known in France as the"Catastrophe ferroviaire de Meudon".The accident was witnessed by the British locomotive engineerJoseph Lockeand widely reported in Britain. It was discussed extensively by engineers, who sought an explanation.

The derailment had been the result of a brokenlocomotiveaxle.Rankine'sinvestigation of broken axles in Britain highlighted the importance of stress concentration, and the mechanism of crack growth with repeated loading. His and other papers suggesting a crack growth mechanism through repeated stressing, however, were ignored, and fatigue failures occurred at an ever-increasing rate on the expanding railway system. Other spurious theories seemed to be more acceptable, such as the idea that the metal had somehow "crystallized". The notion was based on the crystalline appearance of the fast fracture region of the crack surface, but ignored the fact that the metal was already highly crystalline.

de Havilland Comet

[edit]

Twode Havilland Cometpassenger jets broke up in mid-air and crashed within a few months of each other in 1954. As a result, systematic tests were conducted on afuselageimmersed and pressurised in a water tank. After the equivalent of 3,000 flights, investigators at theRoyal Aircraft Establishment(RAE) were able to conclude that the crash had been due to failure of the pressure cabin at the forwardAutomatic Direction Finderwindow in the roof. This 'window' was in fact one of two apertures for theaerialsof an electronic navigation system in which opaquefibreglasspanels took the place of the window 'glass'. The failure was a result of metal fatigue caused by the repeated pressurisation and de-pressurisation of the aircraft cabin. Also, the supports around the windows were riveted, not bonded, as the original specifications for the aircraft had called for. The problem was exacerbated by thepunch rivetconstruction technique employed. Unlike drill riveting, the imperfect nature of the hole created by punch riveting caused manufacturing defect cracks which may have caused the start of fatigue cracks around the rivet.

The Comet's pressure cabin had been designed to asafety factorcomfortably in excess of that required by British Civil Airworthiness Requirements (2.5 times the cabinproof testpressure as opposed to the requirement of 1.33 times and an ultimate load of 2.0 times the cabin pressure) and the accident caused a revision in the estimates of the safe loading strength requirements of airliner pressure cabins.

In addition, it was discovered that thestressesaround pressure cabin apertures were considerably higher than had been anticipated, especially around sharp-cornered cut-outs, such as windows. As a result, all futurejet airlinerswould feature windows with rounded corners, greatly reducing the stress concentration. This was a noticeable distinguishing feature of all later models of the Comet. Investigators from the RAE told a public inquiry that the sharp corners near the Comets' window openings acted as initiation sites for cracks. The skin of the aircraft was also too thin, and cracks from manufacturing stresses were present at the corners.

Alexander L. Kiellandoil platform capsizing

[edit]

Alexander L. Kiellandwas a Norwegiansemi-submersibledrilling rigthatcapsizedwhilst working in theEkofisk oil fieldin March 1980, killing 123 people. The capsizing was the worst disaster in Norwegian waters since World War II. The rig, located approximately 320 km east ofDundee,Scotland, was owned by the Stavanger Drilling Company of Norway and was on hire to the United States companyPhillips Petroleumat the time of the disaster. In driving rain and mist, early in the evening of 27 March 1980 more than 200 men were off duty in the accommodation onAlexander L. Kielland.The wind was gusting to 40 knots with waves up to 12 m high. The rig had just been winched away from theEddaproduction platform. Minutes before 18:30 those on board felt a 'sharp crack' followed by 'some kind of trembling'. Suddenly the rig heeled over 30° and then stabilised. Five of the six anchor cables had broken, with one remaining cable preventing the rig from capsizing. Thelistcontinued to increase and at 18:53 the remaining anchor cable snapped and the rig turned upside down.

A year later in March 1981, the investigative report[58]concluded that the rig collapsed owing to a fatigue crack in one of its six bracings (bracing D-6), which connected the collapsed D-leg to the rest of the rig. This was traced to a small 6 mm fillet weld which joined a non-load-bearing flange plate to this D-6 bracing. This flange plate held a sonar device used during drilling operations. The poor profile of the fillet weld contributed to a reduction in its fatigue strength. Further, the investigation found considerable amounts oflamellar tearingin the flange plate and cold cracks in the butt weld. Cold cracks in the welds, increased stress concentrations due to the weakened flange plate, the poor weld profile, and cyclical stresses (which would be common in theNorth Sea), seemed to collectively play a role in the rig's collapse.

Others

[edit]- The 1862Hartley Colliery Disasterwas caused by the fracture of a steam engine beam and killed 204 people.

- The 1919 BostonGreat Molasses Floodhas been attributed to a fatigue failure.

- The 1948Northwest Airlines Flight 421crash due to fatigue failure in a wing spar root

- The1957 "Mt. Pinatubo",presidential plane ofPhilippine PresidentRamon Magsaysay,crashed due to engine failure caused by metal fatigue.

- The 1965 capsize of the UK's first offshore oil platform, theSea Gem,was due to fatigue in part of the suspension system linking the hull to the legs.

- The 1968Los Angeles Airways Flight 417lost one of its main rotor blades due to fatigue failure.

- The 1968MacRobertson Miller Airlines Flight 1750lost a wing due to improper maintenance leading to fatigue failure.

- The 1969F-111Acrash due to a fatigue failure of the wing pivot fitting from a material defect resulted in the development of thedamage-tolerantapproach for fatigue design.[59]

- The1977 Dan-Air Boeing 707 crashcaused by fatigue failure resulting in the loss of the right horizontal stabilizer.

- The 1979American Airlines Flight 191crashed after engine separation attributed to fatigue damage in the pylon structure holding the engine to the wing, caused by improper maintenance procedures.

- The 1980LOT Flight 7crashed due to fatigue in an engine turbine shaft resulting in engine disintegration leading to loss of control.

- The 1985Japan Airlines Flight 123crashed after the aircraft lost its vertical stabilizer due to faulty repairs on the rear bulkhead.

- The 1988Aloha Airlines Flight 243suffered an explosive decompression at 24,000 feet (7,300 m) after a fatigue failure.

- The 1989United Airlines Flight 232lost its tail engine due to fatigue failure in a fan disk hub.

- The 1992El Al Flight 1862lost both engines on its right-wing due to fatigue failure in the pylon mounting of the #3 Engine.

- The 1998Eschede train disasterwas caused by fatigue failure of a single composite wheel.

- The 2000Hatfield rail crashwas likely caused byrolling contact fatigue.

- The 2000recall of 6.5 million Firestone tireson Ford Explorers originated from fatigue crack growth leading to separation of the tread from the tire.[60]

- The 2002China Airlines Flight 611disintegrated in-flight due to fatigue failure.

- The 2005Chalk's Ocean Airways Flight 101lost its right wing due to fatigue failure brought about by inadequate maintenance practices.

- The 2009Viareggio train derailmentdue to fatigue failure.

- The2009 Sayano–Shushenskaya power station accidentdue to metal fatigue of turbine mountings.

- The 2017Air France Flight 66had in-flight engine failure due to cold dwell fatigue fracture in the fan hub.

- The 2023Titan submersible implosionis thought to have occurred due to fatiguedelaminationof the carbon-fiber material used for the hull.

See also

[edit]- Aviation safety– State in which risks associated with aviation are at an acceptable level

- Basquin's Law of Fatigue

- Critical plane analysis– Analysis of multiaxial stresses and strains

- Embedment

- Forensic materials engineering– branch of forensic engineering

- Fractography– Study of the fracture surfaces of materials

- Smith fatigue strength diagram,a diagram by British mechanical engineerJames Henry Smith

- Solder fatigue– Degradation of solder due to deformation under cyclic loading

- Thermo-mechanical fatigue

- Vibration fatigue

- International Journal of Fatigue

References

[edit]- ^Schijve, J. (2003)."Fatigue of structures and materials in the 20th century and the state of the art".International Journal of Fatigue.25(8): 679–702.doi:10.1016/S0142-1123(03)00051-3.

- ^abcdSuresh, S.(2004).Fatigue of Materials.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-57046-6.

- ^Kim, W. H.; Laird, C. (1978). "Crack nucleation and stage I propagation in high strain fatigue—II. mechanism".Acta Metallurgica.26(5): 789–799.doi:10.1016/0001-6160(78)90029-9.

- ^abMurakami, Y.; Miller, K. J. (2005). "What is fatigue damage? A view point from the observation of low cycle fatigue process".International Journal of Fatigue.27(8): 991–1005.doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2004.10.009.

- ^Forsythe, P. J. E. (1953). "Exudation of material from slip bands at the surface of fatigued crystals of an aluminium-copper alloy".Nature.171(4343): 172–173.Bibcode:1953Natur.171..172F.doi:10.1038/171172a0.S2CID4268548.

- ^Schijve, J. (1978)."Internal fatigue cracks are growing in vacuum".Engineering Fracture Mechanics.10(2): 359–370.doi:10.1016/0013-7944(78)90017-6.

- ^Pearson, S. (1975). "Initiation of fatigue cracks in commercial aluminium alloys and the subsequent propagation of very short cracks".Engineering Fracture Mechanics.7(2): 235–247.doi:10.1016/0013-7944(75)90004-1.

- ^Pippan, R.; Hohenwarter, A. (2017)."Fatigue crack closure: a review of the physical phenomena".Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures.40(4): 471–495.doi:10.1111/ffe.12578.PMC5445565.PMID28616624.

- ^abASTM Committee E08.06 (2013).E647 Standard Test Method for Measurement of Fatigue Crack Growth Rates(Technical report). ASTM International. E647-13.

{{cite tech report}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Fleck, N. A.; Shin, C. S.; Smith, R.A. (1985). "Fatigue Crack Growth Under Compressive Loading".Engineering Fracture Mechanics.21(1): 173–185.doi:10.1016/0013-7944(85)90063-3.

- ^abSchutz, W. (1996). "A history of fatigue".Engineering Fracture Mechanics.54(2): 263–300.doi:10.1016/0013-7944(95)00178-6.

- ^Rankine, W. J. M. (1843)."On the causes of the unexpected breakage of the journals of railway axles, and on the means of preventing such accidents by observing the law of continuity in their construction".Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers.2(1843): 105–107.doi:10.1680/imotp.1843.24600.

- ^Braithwaite, F. (1854)."On the fatigue and consequent fracture of metals".Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers.13(1854): 463–467.doi:10.1680/imotp.1854.23960.

- ^Basquin, O. H. (1910). "The exponential law of endurance test".Proceedings of the American Society for Testing and Materials.10:625–630.

- ^Cadwell, Sidney; Merrill; Sloman; Yost (1940). "Dynamic fatigue life of rubber".Rubber Chemistry and Technology.13(2): 304–315.doi:10.5254/1.3539515.

- ^abMiner, M. A. (1945). "Cumulative damage in fatigue".Journal of Applied Mechanics.12:149–164.

- ^Palmgren, A. G. (1924). "Die Lebensdauer von Kugellagern" [Life Length of Roller Bearings].Zeitschrift des Vereines Deutscher Ingenieure(in German).68(14): 339–341.

- ^Murray, W.M., ed. (1952). "The statistical aspect of fatigue failure and its consequences".Fatigue and Fracture of Metals.Technology Press of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Wiley. pp. 182–196.

- ^Matsuishi, M.; Endo, T. (1968).Fatigue of Metals Subjected to Varying Stress.Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- ^Smith, K.N.; Watson, P.; Topper, T.H. (1970). "A stress-strain function for the fatigue of metals".Journal of Materials.5(4): 767–778.

- ^Elber, Wolf (1970). "Fatigue crack closure under cyclic tension".Engineering Fracture Mechanics.2:37–45.

- ^Elber, Wolf (1971).The Significance of Fatigue Crack Closure, ASTM STP 486.American Society for Testing and Materials. pp. 230–243.

- ^Brown, M. W.; Miller, K. J. (1973). "A theory for fatigue failure under multiaxial stress-strain conditions".Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers.187(1): 745–755.doi:10.1243/PIME_PROC_1973_187_161_02.

- ^Stephens, R. I.; Fuchs, H. O. (2001).Metal Fatigue in Engineering(2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p.69.ISBN978-0-471-51059-8.

- ^Bathias, C. (1999). "There is no infinite fatigue life in metallic materials".Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures.22(7): 559–565.doi:10.1046/j.1460-2695.1999.00183.x.

- ^Pyttel, B.; Schwerdt, D.; Berger, C. (2011-01-01)."Very high cycle fatigue – Is there a fatigue limit?".International Journal of Fatigue.Advances in Very High Cycle Fatigue.33(1): 49–58.doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2010.05.009.ISSN0142-1123.

- ^Sonsino, C (December 2007)."Course of SN-curves especially in the high-cycle fatigue regime with regard to component design and safety".International Journal of Fatigue.29(12): 2246–2258.doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2006.11.015.

- ^Mughrabi, H. (2002)."On 'multi-stage' fatigue life diagrams and the relevant life-controlling mechanisms in ultrahigh-cycle fatigue".Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures.25(8–9): 755–764.doi:10.1046/j.1460-2695.2002.00550.x.ISSN1460-2695.

- ^Shigley, J. E.; Mischke, C. R.; Budynas, R. G. (2003).Mechanical Engineering Design(7th ed.).McGraw Hill Higher Education.ISBN978-0-07-252036-1.

- ^Eskandari, H.; Kim, H. S. (2017). "A theory for mathematical framework and fatigue damage function for S-N plane". In Wei, Z.; Nikbin, K.; McKeighan, P. C.; Harlow, G. D. (eds.).Fatigue and Fracture Test Planning, Test Data Acquisitions and Analysis.ASTM Selected Technical Papers. Vol. 1598. pp. 299–336.doi:10.1520/STP159820150099.ISBN978-0-8031-7639-3.

- ^Burhan, Ibrahim; Kim, Ho Sung (September 2018)."S-N Curve Models for Composite Materials Characterisation: An Evaluative Review".Journal of Composites Science.2(3): 38–66.doi:10.3390/jcs2030038.

- ^Weibull, Waloddi(1961).Fatigue testing and analysis of results.Oxford: Published for Advisory Group for Aeronautical Research and development, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, by Pergamon Press.ISBN978-0-08-009397-0.OCLC596184290.

- ^Kim, Ho Sung (2019-01-01)."Prediction of S-N curves at various stress ratios for structural materials".Procedia Structural Integrity.Fatigue Design 2019, International Conference on Fatigue Design, 8th Edition.19:472–481.doi:10.1016/j.prostr.2019.12.051.ISSN2452-3216.

- ^Kawai, M.; Itoh, N. (2014). "A failure-mode based anisomorphic constant life diagram for a unidirectional carbon/epoxy laminate under off-axis fatigue loading at room temperature".Journal of Composite Materials.48(5): 571–592.Bibcode:2014JCoMa..48..571K.CiteSeerX10.1.1.826.6050.doi:10.1177/0021998313476324.S2CID137221135.

- ^Kim, H. S. (2016).Mechanics of Solids and Fracture(2nd ed.). Ventus Publishing.ISBN978-87-403-1395-6.

- ^Beardmore, R. (13 January 2013)."Fatigue Stress Action Types".Roymechx. Archived fromthe originalon 12 January 2017.Retrieved29 April2012.

- ^tec-science (2018-07-13)."Fatigue test".tec-science.Retrieved2019-10-25.

- ^ASM Handbook, Volume 19 - Fatigue and Fracture.Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. 1996. p. 21.ISBN978-0-87170-377-4.OCLC21034891.

- ^Pearson, S. (1975). "Initiation of fatigue cracks in commercial aluminum alloys and the subsequent propagation of very short cracks".Engineering Fracture Mechanics.7(2): 235–247.doi:10.1016/0013-7944(75)90004-1.

- ^Sunder, R.; Seetharam, S. A.; Bhaskaran, T. A. (1984). "Cycle counting for fatigue crack growth analysis".International Journal of Fatigue.6(3): 147–156.doi:10.1016/0142-1123(84)90032-X.

- ^Udomphol, T. (2007)."Fatigue of metals"(PDF).Suranaree University of Technology. p. 54. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2013-01-02.Retrieved2013-01-26.

- ^Lincoln, J. W. (1985). "Risk assessment of an aging military aircraft".Journal of Aircraft.22(8): 687–691.doi:10.2514/3.45187.

- ^"Material Technologies, Inc. Completes EFS Inspection of Bridge in New Jersey"(Press release). Material Technologies. 17 April 2007.

- ^"High Interference Bushing Installation".Fatigue Technology. Archived fromthe originalon 24 June 2019.Retrieved24 June2019.

- ^Baker, Alan (2008).Structural Health Monitoring of a Bonded composite Patch Repair on a Fatigue-Cracked F-111C Wing(PDF).Defence Science and Technology Organisation.Archived(PDF)from the original on June 24, 2019.Retrieved24 June2019.

- ^Hoffer, W. (June 1989)."Horrors in the Skies".Popular Mechanics.166(6): 67–70, 115–117.

- ^Can Yildirim, H.; Marquis, G. B. (2012). "Fatigue strength improvement factors for high strength steel welded joints treated by high frequency mechanical impact".International Journal of Fatigue.44:168–176.doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2012.05.002.

- ^Can Yildirim, H.; Marquis, G. B.; Barsoum, Z. (2013). "Fatigue assessment of High Frequency Mechanical Impact (HFMI)-improved fillet welds by local approaches".International Journal of Fatigue.52:57–67.doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2013.02.014.

- ^"Cold work bush installation".Fatigue Technology. Archived fromthe originalon 2019-09-02.Retrieved20 July2019.

- ^"Research (Laser Peening)".LAMPL.

- ^"Search Results for 'fatigue'".Cryogenic Treatment Database.

- ^"Airframe Life Extension by Optimised Shape Reworking"(PDF).Retrieved24 June2019.

- ^Tetelman, A. S. (1969)."Fracture Processes in Fiber Composite Materials".Composite Materials: Testing and Design.pp. 473–502.doi:10.1520/STP49836S.ISBN978-0-8031-0017-6.Retrieved2022-05-20.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^abCorten, H. T. (1972).Composite Materials: Testing and Design: a Conference.ASTM International.ISBN978-0-8031-0134-0.

- ^Rotem, A.; Nelson, H. G. (1989-01-01)."Failure of a laminated composite under tension—compression fatigue loading".Composites Science and Technology.36(1): 45–62.doi:10.1016/0266-3538(89)90015-8.ISSN0266-3538.

- ^Courtney, Thomas H. (2005-12-16).Mechanical Behavior of Materials: Second Edition.Waveland Press.ISBN978-1-4786-0838-7.

- ^"ObjectWiki: Fuselage of de Havilland Comet Airliner G-ALYP".Science Museum. 24 September 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 7 January 2009.Retrieved9 October2009.

- ^The Alexander L. Kielland accident, Report of a Norwegian public commission appointed by royal decree of March 28, 1980, presented to the Ministry of Justice and Police March.Norwegian Public Reports 1981:11. Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. 1981.ASINB0000ED27N.

- ^Redmond, Gerard."From 'Safe Life' to Fracture Mechanics - F111 Aircraft Cold Temperature Proof Testing at RAAF Amberley".Archived fromthe originalon 27 April 2019.Retrieved17 April2019.

- ^Ansberry, C. (5 February 2001)."In Firestone Tire Study, Expert Finds Vehicle Weight Was Key in Failure".Wall Street Journal.Retrieved6 September2016.

Further reading

[edit]- PDL Staff (1995).Fatigue and Tribological Properties of Plastics and Elastomers.Plastics Design Library.ISBN978-1-884207-15-0.

- Leary, M.; Burvill, C. (2009). "Applicability of published data for fatigue-limited design".Quality and Reliability Engineering International.25(8): 921–932.doi:10.1002/qre.1010.S2CID206432498.

- Dieter, G. E. (2013).Mechanical Metallurgy.McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-1259064791.

- Little, R.E.; Jebe, E.H. (1975).Statistical Design of Fatigue Experiments.John Wiley & Sons.ISBN978-0-470-54115-9.

- Schijve, J. (2009).Fatigue of Structures and Materials.Springer.ISBN978-1-4020-6807-2.

- Lalanne, C. (2009).Fatigue Damage.ISTE-Wiley.ISBN978-1-84821-125-4.

- Pook, L. (2007).Metal Fatigue, What it is, Why it matters.Springer.ISBN978-1-4020-5596-6.

- Draper, J. (2008).Modern Metal Fatigue Analysis.EMAS.ISBN978-0-947817-79-4.

- Suresh, S. (2004).Fatigue of Materials.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-57046-6.

- Kim, H. S. (2018).Mechanics of Solids and Fracture, 3rd ed.Bookboon, London.ISBN978-87-403-2393-1.

External links

[edit]- FatigueShawn M. Kelly

- Application note on fatigue crack propagation in UHMWPEArchived2013-11-04 at theWayback Machine

- fatigue test videoKarlsruhe University of Applied Sciences

- Strain life methodG. Glinka

- Fatigue from variable amplitude loadingA. Fatemi