Feral pig

Aferal pigis adomestic pigwhich has goneferal,meaning it lives in the wild. The term feral pig has also been applied towild boars,which can interbreed with domestic pigs.[1]They are found mostly inthe AmericasandAustralia.Razorbackandwild hogare sometimes used in theUnited Statesrefer to feral pigs orboar–pig hybrids.

Definition

Aferalpig is adomestic pigthat has escaped or been released into the wild, and is living more or less as a wild animal, or one that is descended from such animals.[2]Zoologists generally exclude from theferalcategory animals that, although captive, were genuinely wild before they escaped.[3]Accordingly, Eurasianwild boar,released or escaped into habitats where they are not native, such as in North America, are not generally considered feral, although they may interbreed with feral pigs.[4]Likewise, reintroduced wild boars in Western Europe are also not considered feral, despite the fact that they were raised in captivity prior to their release.

North America

Domestic pigs were first introduced tothe Americasin the 16th century.[5]Christopher Columbusintentionally released domestic swine in theWest Indiesduring his second voyage to provide future expeditions with a freely available food supply.[6]Hernando de Sotois known to have introduced Eurasian domestic swine to Florida in 1539,[7]though it is possible thatJuan Ponce de Leónhad already introduced the first pigs into mainland Florida in 1521.[8]

The practice of introducing domestic pigs into theNew Worldpersisted throughout the exploration periods of the 16th and 17th centuries.[5]The Eurasian wild boar (S. s. scrofa), which originally ranged from Great Britain to European Russia, may have also been introduced.[9]By the 19th century, their numbers were sufficient in some areas such as theSouthern United Statesto become a commongame animal.

Feral pigs are a growing problem in the United States and also on the southernprairies in Canada.[10]As of 2013[update],the estimated population of 6million[11]feral pigs causes billions of dollars in property and agricultural damage every year in the United States,[citation needed]both in wild and agricultural lands. Their ecological damage may be equally problematic with 26% lower vertebrate species richness in forest fragments they have invaded.[12]Because pigs forage by rooting for their food under the ground with their snouts and tusks, a group of feral pigs can damage acres of planted fields in just a few nights.[11]Due to the feral pig'somnivorousnature, it is a danger to both plants and animals endemic to the area it is invading. Game animals such asdeerandturkeys,and more specifically, flora such as theOpuntiaplant have been especially affected by the feral hog's aggressive competition for resources.[13]Feral pigs have been determined to be potential hosts for at least 34pathogensthat can be transmitted to livestock, wildlife, and humans.[14]For commercial pig farmers, great concern exists that some of the hogs could be avectorforswine feverto return to the U.S., which has been extinct in America since 1978. Feral pigs could also present an immediate threat to "nonbiosecure" domestic pig facilities because of their likeliness to harbor and spread pathogens, particularly the protozoanSarcocystis.[15]

By the early 2000s, the range of feral pigs included all of the U.S. south of36° north.The range begins in the mountains surrounding California[16]and crosses over the mountains, continuing consistently much farther east towards theLouisianabayous and forests, terminating in the entire Florida peninsula. In the East, the range expands northward to include most of the forested areas and swamps of the Southeast, and from there goes north along theAppalachian Mountainsas far as upstateNew York,with a growing presence in states borderingWest VirginiaandKentucky.Texashas the largest estimated population of 2.5–2.6million feral pigs existing in 253 of its 254 counties,[17]and they cause about $50million in agriculture damage per year.

Hunting in the United States

To control feral pig numbers, Americanhuntershave taken to trapping and killing as many individuals as they can. Some, in Texas, have even turned the trapping and killing of razorbacks into small businesses.[19][20][21]The meat of wild pigs may be suitable for human consumption; around 461,000 animals killed in Texas between 2004 and 2009 were federally inspected and commercially sold for consumption.[22]

Legal restrictions on methods of hunting are lax, as most state departments of wildlife openly acknowledge feral pigs as an ecological threat and some classify them as vermin. For example, theWisconsin Department of Natural Resourcesconsiders them unprotected wild animals with no closed season or harvest limit, and promotes their aggressive removal.[23]

Shooting pigs from a helicopter is legal in Texas, and can be an effective method, killing as many as 9 to 27 animals per hour.[24]Helicopters can cost from US$400 to US$1000 per hour to operate. These costs are defrayed by selling seats on these helicopter flights to recreational hunters; Texas law only requires that those buying a helicopter hunt be in possession of a hunting license. The method relies on the helicopter flushing pigs into the open where they can be targeted. In some areas, such as thePiney Woods,this may not be possible because of vegetation.[25]

Hunting with dogs is permitted and very common; it has been practiced in the Southeast for generations. Competitions for producing the fastestbay dogsare prevalent in the South, withUncle Earl's Hog Dog TrialsinLouisianaa popular example, held every summer since 1995. Preferredscent dogsfor catching feral pigs mostly are native breeds, and include theCatahoula Leopard Dog,theBlue Lacy,theLeopard Hound,all six of theCoonhoundbreeds, and theBlackmouth Cur.

Catch dogstypically areAmerican Pit Bull Terriersand theircrosses,the Catahoula (dual purpose), theDogo Argentino,a dog used for the same purpose in South America, andAmerican Bulldogs;the first of these has been put back to work as a utility breed[26][27]over the past 30 years and its tenacity on the hunt and undying loyalty to protect its master have made it a popular asset.[28][29]The method of hunting has little variation: usually, the hunter sends out bay dogs trained to chase the pig until it tires and then corner it; then a biggercatch dogis sent out to catch and hold down the pig, which may get aggressive, until the hunter arrives to kill it.[30][31][32]

No single management technique alone can be totally effective at controlling feral pig populations. Harvesting 66% of the total population per year is required to keep the Texas feral pig populations stable.[33]Best management practices suggest the use of corral traps which have the ability to capture the entire sounder of feral pigs. The federal government spends $20million on feral pig management.[34]

In February 2017, Texas Agriculture CommissionerSid Millerapproved the use of a pesticide called Kaput Feral Hog Lure, which is bait food laced withwarfarin(arodenticideused to killrodents).[35]

Hawaii

A genetic analysis found that the first pigs were introduced to Hawaii byPolynesiansin approximately AD 1200.[36]Additional varieties of European pigs were introduced after Captain Cook's arrival into Hawaii in 1778,[37]where they prey on or eat endangered birds and plants. The population of feral pigs has increased from 2 million pigs ranging over 20 states in 1990, to triple that number 25 years later, ranging over 38 states with new territories expanding north intoOregon,Pennsylvania,Ohio,andNew Hampshire.Some of these feral pigs have mixed with escaped Russian boars that have been introduced for hunters since the early 1990s.[38]

Feral pigs are opportunistic omnivores, with about 85%-90% of their diet being plant matter, and the remainder animal.[22]Plants have difficulties regenerating from their wallowing, as North American flora did not evolve to withstand the destruction caused by rooting pigs, unlike European or Asian flora.[39]Feral pigs in the U.S. eat small animals, mostly invertebrates like insects and worms but also vertebrates such aswild turkeypoults,toads,tortoises,and theeggsof reptiles and birds.[40]This can deprive other wildlife that normally would feed upon these important food sources.

In some case, other wildlife are out-competed by the feral pigs' higher reproductive rate; a sow can become pregnant as early as six months old and give birth to multiple litters of piglets yearly.[22]In the autumn, other animals such as theAmerican black bearcompete directly with feral pigs as both forage fortree mast(the fruit of forest trees).[41]These are likely reasons that they reduce diversity when they invade.[12]

In the U.S., the problems caused by feral pigs are exacerbated by the small number of species which prey on them. Predators such asbobcatsandcoyotesmay occasionally take feral piglets or weakened animals, but are not large enough to challenge a full-grown boar that can grow to three times their weight. In Florida, feral pigs made up a significant portion of theFlorida panther's diet.[42]Other potential predators include thegray wolf,red wolf,cougar,jaguar,American alligator,American black bear, andgrizzly bear.Unfortunately, each keystone predator presents problems: the jaguar is extirpated from California and theSouthwest.The grizzly bear, while native to most of the American West, is gone from the states that have large feral pig populations, namely Texas,Arizona,California, andNew Mexico;and the species also has a very slow reproductive rate. Wolf numbers are small and expected to remain so as they slowly repopulate their range; only a few individuals thus far have been recorded as inhabiting California, in spite of thousands of square miles of good habitat. The cougar is present in most of the West, but is gone from the East, with no known populations east of Minnesota in the north, and very thin numbers east ofHoustonin the South. The American black bear is both predator and competitor, but in most areas probably may not impact feral pig populations enough to control them. Programs do exist to protect the weakened numbers of large predators in the U.S., but it is expected to take a very long time for these animals to naturally repopulate their former habitat.[43]

South America

In South America, during the early 20th century, free-ranging boars were introduced in Uruguay for hunting purposes and eventually crossed the border into Brazil in the 1990s, quickly becoming aninvasive species.Licensed private hunting of both feral boars and their hybrids with domestic pigs was authorized from August 2005 on in the southern Brazilian state ofRio Grande do Sul,[44]although their presence as a pest had been already noticed by the press as early as 1994.[45]Releases and escapes from unlicensed farms (established because of increased demand for boar meat as an alternative to pork) continued to bolster feral populations and, by mid-2008, licensed hunts had to be expanded to the states ofSanta CatarinaandSão Paulo.[46]

Recently established Brazilian boar populations are not to be confused with long-established populations of feral domestic pigs, which have existed mainly in thePantanalfor more than 100 years, along with nativepeccaries.The demographic dynamics of the interaction between feral pig populations and those of the two native species of peccaries (collared peccaryandwhite-lipped peccary) is obscure and is still being studied. The existence of feral pigs could somewhat easejaguarpredation on peccary populations, as jaguars show a preference for hunting pigs when they are available.[47]

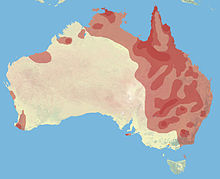

Australia

The first recorded release of pigs in Australia was made byCaptain James CookatAdventure Bay,Bruny Islandin 1777. This was part of his policy of introducing animals and plants to newly discovered countries. He "carried them (a boar and sow) about a mile within the woods at the head of the bay and there left them by the side of a fresh water brook". The deliberate introduction of pigs into previously pig-free areas seems to have been common. As recently as the early 1970s, pigs were introduced toBabel Island,off the east coast ofFlinders Island.These pigs were eradicated by Department of Agriculture staff with local assistance.[48]

One common story about the feral pig population on Flinders Island is that pigs were released when the shipCity of Foo Chowwent ashore on the northeast coast of the island in March 1877. On Flinders Island, feral pigs usually invade agricultural areas adjacent to the national park and east-coast swamps. Farmers consider damage caused by the pigs to be minor, as it is restricted to rooting in pasture adjacent to scrubland edges. The total pasture area damaged each year is estimated to be less than 50 hectares. Feral pigs are reported to visit paddocks where ewes are lambing, but no lambs are reported as having been killed. Asomnivores,they may scavenge any carcasses left near the scrubland, thus developing a potential "taste" for lamb or mutton. In theStrzelecki National Parkon the island, the ecosystem has been severely damaged; extensive rooting in the gullies led to water erosion and loss of regenerating forest plants.Bracken fern(Pteridium esculentum) flourishes in this damaged environment and dominates large areas forming dense stands to about 4 m which prevent light reaching theforest floor.[48]

Since 1987, feral pigs have been considered to be the most important mammalian pest of Australian agriculture.[48]Feral pigs may be a new food source for crocodiles, helping to boost their population.[49][50]

While no incidences of feral pigs killing newborn lambs have been recorded in Australia, the same cannot be said in nearbyNew Zealand,where feral pigs have been seen with some regularity in and around the island nation's capital ofWellington.[51]Here, they have been documented killing and consuming newborn/juvenile dairy goats kept on farms, separating the youngest goats from the rest of the herd; the feral pigs (which usually raid the farms by cover of darkness) will also threaten any guard dogs present into submission, in order to attack and eat the goat kids. As of September 2022, one single goat farm in the suburb ofBrooklynhas estimated their total loss to feral hogs to be at least 60 kids.[51]According to property co-owner Naomi Steenkamp, "It's a murder scene", with the morning revealing evidence of the previous night's carnage—bone fragments, such as bits of hoof and skull, are often all that remain of the helpless young goats. Additionally, Steenkamp has stated that "...If they [feral pigs] find something they like eating, and it is a free feed – like a newborn kid – they are going to keep coming back."[51]The pigs also damage the nesting sites of New Zealand's endemic wildlife, includingkiwiand other ground-nesting and flightless birds, and may target chicks and eggs for food, as well as adult birds.

Fatal attacks on human beings

Feral pigs can be dangerous to people, particularly when the pigs travel in herds with their young, and should be avoided when possible. Feral pigs living in the United States have been known to attack without provocation and fatally injure human beings. There have been over 100 documented attacks by feral pigs on human beings in the United States between the years 1825 and 2012. Of these attacks, five have been fatal. Three of the five fatal attacks were by feral pigs wounded by hunters. Both male and female feral pigs are known to attack without provocation, and attacks by solitary males, as well as group attacks have been documented.[52][53][54]

On November 26, 2019, a 59-year-old Texas woman named Christine Rollins was attacked and killed only a few feet away from the front door of her workplace by a herd of feral pigs in the town ofAnahuac, Texas,which is 50 miles east of Houston. This incident was the fifth documented fatal feral pig attack in the United States since 1825.[52]Chambers CountySheriff Brian Hawthorne in a formal statement to news media stated that "multiple hogs" assaulted Rollins during pre-dawn hours between 6 and 6:30 a.m. when it was still dark outside. The victim died of blood loss as a result of her injuries.[55]

See also

References

- ^"An Overview of Wild Pigs | Wild Pigs".wildpigs.nri.tamu.edu.RetrievedJuly 5,2023.

- ^Cf."feral".Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.RetrievedNovember 20,2014.

- ^Lever, C. (1996). "Naturalized birds: Feral, exotic, introduced or alien?".British Birds.89(8): 367–368.

- ^John J. Mayer; I. Lehr Brisbin, Jr. (March 1, 2008).Wild Pigs in the United States: Their History, Comparative Morphology, and Current Status.University of Georgia Press. pp. 1–3.ISBN978-0-8203-3137-9.RetrievedNovember 20,2014.

- ^ab"tworiversoutdoorclub".tworiversoutdoorclub.Archived fromthe originalon July 17, 2011.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^"History and Distribution of Feral Hogs in Texas".AgriLife.org.Archived fromthe originalon April 13, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 2,2016.

- ^Woodward, Susan L.; Quinn, Joyce A. (September 30, 2011).Encyclopedia of Invasive Species: From Africanized Honey Bees to Zebra Mussels.ABC-CLIO. pp. 277–.ISBN978-0-313-38220-8.

- ^Mayer, John J.; Brisbin, I. Lehr Jr. (March 1, 2008).Wild Pigs in the United States: Their History, Comparative Morphology, and Current Status.University of Georgia Press. pp. 20ff.ISBN978-0-8203-3137-9.RetrievedDecember 26,2011.

- ^Scheggi, Massimo (1999).La Bestia Nera: Caccia al Cinghiale fra Mito, Storia e Attualità(in Italian). Editoriale Olimpia. p. 201.ISBN88-253-7904-8.

- ^Kaufmann, Bill (March 23, 2013)."Alberta bringing in bounty to deal with brewing wild boar woes".Calgary Sun.Archived fromthe originalon September 12, 2014.

- ^ab"Feral pigs: Pork, chopped".The Economist.May 4, 2013.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^abIvey, Matthew R.; Colvin, Michael; Strickland, Bronson K.; Lashley, Marcus A. (June 14, 2019)."Reduced vertebrate diversity independent of spatial scale following feral swine invasions".Ecology and Evolution.9(13): 7761–7767.doi:10.1002/ece3.5360.ISSN2045-7758.PMC6635915.PMID31346438.

- ^Taylor, Richard B.; Hellgren, Eric C. (1997). "Diet of Feral Hogs in the Western South Texas Plains".The Southwestern Naturalist.42(1): 33–39.JSTOR30054058.

- ^Miller, R. S.; Sweeney, S. J.; Slootmaker, C.; Grear, D. A.; Di Salvo, P. A.; Kiser, D.; Shwiff, S. A. (2017)."Cross-species transmission potential between wild pigs, livestock, poultry, wildlife, and humans: Implications for disease risk management in North America".Scientific Reports.7(1): 7821.Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.7821M.doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07336-z.PMC5552697.PMID28798293.

- ^Calero-Bernal, R.; Verma, S. K.; Oliveira, S.; Yang, Y.; Rosenthal, B. M.; Dubey, J. P. (April 1, 2015). "In the United States, negligible rates of zoonotic sarcocystosis occur in feral swine that, by contrast, frequently harbour infections withSarcocystis miescheriana,a related parasite contracted from canids ".Parasitology.142(4): 549–56.doi:10.1017/S0031182014001553.PMID25363485.S2CID44325702.

- ^Dowd, Katie (December 26, 2019)."One eccentric socialite is to blame for California's wild pig problem".sfgate.RetrievedDecember 28,2019.

- ^"Coping with Feral Hogs".Texas A&M University.March 25, 2014.RetrievedMarch 25,2014.

- ^JAGER PRO (March 24, 2015).Hog Trapping with Integrated Wild Pig Control(Video).Archivedfrom the original on November 18, 2021.

- ^Horansky, Andrew (April 26, 2013)."High tech hunting for Texas feral hogs".Houston:KHOU.Archived fromthe originalon February 22, 2014.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^Hawkes, Logan (May 17, 2013)."Feral hog control the military way".Southeast Farm Press.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^Ramchandani, Ariel (March 15, 2017)."The Business of Shooting Pigs from the Sky".Pacific Standard.RetrievedMarch 17,2017.

- ^abc"Frequently Asked Questions-Wild Pigs: Coping with Feral Hogs".FeralHogs.TAMU.edu.Texas A&M University. Archived fromthe originalon January 12, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^"Feral Pig Control".DNR.Wi.gov.Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.RetrievedNovember 23,2015.

- ^Campbell, Tyler; Long, David; Leland, Bruce (2010).Feral Swine Behavior Relative to Aerial Gunning in Southern Texas(Report). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. Vol. 886. University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- ^Gaskins, Dan (November 25, 2013)."The Porkchopper: Aerial Hunting of Feral Hogs".Wild Wonderings Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute.RetrievedNovember 27,2019.

- ^""Pit Bull" Is Not a Breed ".Pitbullinfo.org.

- ^"American Pit Bull Terrier".April 5, 2017.

- ^"Dogging Hogs".Alabama Outdoor News.January 28, 2020.

- ^"Using Pit Bulls for Hog Hunting".Good Pit Bulls.September 21, 2012.

- ^"Cur Dog History".HuntingDogOS.Archived fromthe originalon June 12, 2009.RetrievedSeptember 6,2017.

- ^Rodriguez, Greg."Boar Guide".Archived fromthe originalon February 27, 2009.RetrievedNovember 14,2014.

- ^"Hog Hunting supplies".For All Your Hunting Needs.

- ^"Feral Hog Population Growth and Density in Texas"(PDF).Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. October 2012.RetrievedNovember 6,2014.

- ^"APHIS National Feral Swine Damage Management Program".United States Department of Agriculture.RetrievedFebruary 3,2017.

- ^"Fearing" feral hog apocalypse, "Texas approves drastic measures".CBS News.February 21, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 28,2017.

- ^Linderholm, Anna; Spencer, Daisy; Battista, Vincent; Frantz, Laurent; Barnett, Ross; Fleischer, Robert C.; James, Helen F.; Duffy, Dave; Sparks, Jed P.; Clements, David R.; Andersson, Leif; Dobney, Keith; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Larson, Greger (2016)."A novel MC1R allele for black coat colour reveals the Polynesian ancestry and hybridization patterns of Hawaiian feral pigs".Royal Society Open Science.3(9): 160304.Bibcode:2016RSOS....360304L.doi:10.1098/rsos.160304.ISSN2054-5703.PMC5043315.PMID27703696.

- ^Downes, Lawrence (May 19, 2013)."In pursuit of Hawaii's wild feral pigs".The Seattle Times.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^Goode, Erica (April 27, 2013)."When One Man's Game Is Also a Marauding Pest".The New York Times.RetrievedSeptember 6,2017.

- ^Giuliano, William M. (February 5, 2013)."Wild Hogs in Florida: Ecology and Management".Electronic Data Information Source.Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Archived fromthe originalon March 9, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 2,2016.

- ^"Feral Hogs – Wildlife Enemy Number One".Outdoor Alabama.Archived fromthe originalon February 6, 2014.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^"Black Bears – Great Smoky Mountains National Park".US National Park Service.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^"Wild Hogs in Florida: An Overview"(PDF).MyFWC.Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.RetrievedFebruary 10,2014.

- ^"Natural Predators of Feral Hogs".eXtension.Archived fromthe originalon February 2, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 2,2016.

- ^Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Maturais Nenováveis (August 4, 2005)."Instrução Normativa No. 71"(PDF).Federal Ministério do Meio Ambiente (Brazil).RetrievedFebruary 13,2009.

- ^"Javali: Fronteiras rompidas" [Boars break across the border].Globo Rural.January 1994. pp. 32–35.ISSN0102-6178.

- ^Cecconi, Eduardo (February 13, 2009)."A técnica da caça do javali: Reprodução desordenada do animal é combatida com o abate".Terra de Mauá. Archived fromthe originalon November 19, 2008.

- ^Furtado, Fred (February 13, 2009)."Invasor ou vizinho? Invasor ou vizinho? Estudo traz nova visão sobre interação entre porco-monteiro e seus 'primos' do Pantanal".Ciencia Hoje. Archived fromthe originalon September 6, 2008.

- ^abcStatham, M.; Middleton, M. (1987)."Feral pigs on Flinders Island".Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania.121:121–124.doi:10.26749/rstpp.121.121.

- ^Osbourne, Margaret (May 17, 2022)."Feral Pigs May Have Helped Boost Crocodile Numbers in the Northern Territory, Australia".Smithsonian.RetrievedMay 30,2022.

- ^Ham, Anthony (August 15, 2022)."Pigs to the Rescue: An Invasive Species Helped Save Australia's Crocodiles".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.RetrievedAugust 15,2022.

- ^abcCorlett, Eva @evacorlett (September 26, 2022)."'It's a murder scene': feral pigs torment residents in New Zealand capital; Farm just minutes from centre of Wellington estimates it has lost about 60 kid goats in past few months ".The Guardian.RetrievedApril 9,2023.

- ^ab"Feral Hogs Attack and Kill a Woman in Texas".The New York Times.November 26, 2019.RetrievedDecember 1,2019.

- ^Mayer, John J. (April 3, 2014)."Wild Pig Attacks on Humans".Proceedings of the 15th Wildlife Damage Management Conference.Wildlife Damage Management Conference.RetrievedDecember 6,2019.

- ^"Wild pig attacks on humans,University of Nebraska, Lincoln Peer Reviewed Study".

- ^Johnson, Lauren M. (November 26, 2019)."Feral hogs in Texas attacked and killed a woman outside a home".CNN.RetrievedNovember 29,2019.

External links

- Coping With Feral Hogs

- Feral Hogs and AgricultureArchivedNovember 9, 2015, at theWayback Machine

- U.S. distribution maps by county