Finger

| Finger | |

|---|---|

The fingers of a left hand seen from both sides | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | digiti manus |

| MeSH | D005385 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.030 |

| TA2 | 150 |

| FMA | 9666 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Afingeris a prominentdigiton theforelimbsof mosttetrapodvertebrateanimals,especially those withprehensileextremities (i.e.hands) such ashumansand otherprimates.Most tetrapods have five digits (pentadactyly),[1][2]and short digits (i.e. significantly shorter than themetacarpal/metatarsals) are typically referred to astoes,while those that are notably elongated are called fingers. In humans, the fingers are flexiblyarticulatedandopposable,serving as an important organ oftactile sensationandfine movements,which are crucial to thedexterityof the hands and the ability tograspandmanipulate objects.

Land vertebrate fingers

[edit]As terrestrial vertebrates wereevolvedfromlobe-finned fish,their forelimbs arephylogeneticallyequivalent to thepectoral finsof fish. Within thetaxaof the terrestrial vertebrates, the basic pentadactyl plan, and thus also themetacarpalsandphalanges,undergo many variations.[3] Morphologicallythe different fingers of terrestrial vertebrates arehomolog.The wings of birds and those ofbatsare not homologous, they areanalogueflight organs. However, thephalangeswithin them are homologous.[4]

Chimpanzeeshavelower limbsthat are specialized for manipulation, and (arguably) have fingers (instead oftoes) on their lower limbs as well. In the case ofprimatesin general, the digits of the hand are overwhelmingly referred to as "fingers".[5][6]Primate fingers have bothfingernailsandfingerprints.[7]

Research has been carried out on theembryonic developmentofdomestic chickensshowing that aninterdigital webbingforms between the tissues that become the toes, which subsequently regresses byapoptosis.If apoptosis fails to occur, the interdigital skin remains intact. Many animals have developedwebbed feetor skin between the fingers from this like theWallace's flying frog.[8][9][10]

Human fingers

[edit]Usually humans have five digits,[11]the bones of which are termed phalanges,[2]on each hand, although some people have more or fewer than five due tocongenital disorderssuch aspolydactylyoroligodactyly,or accidental or intentionalamputations.The first digit is thethumb,followed by theindex finger,middle finger,ring finger,andlittle fingeror pinkie. According to different definitions, the thumb can be called a finger, or not.

English dictionaries describe finger as meaning either one of thefive digitsincluding the thumb, or one of thefour digitsexcluding the thumb (in which case they are numbered from 1 to 4 starting with theindex fingerclosest to the thumb).[1][2][12]

Structure

[edit]Skeleton

[edit]

The thumb (connected to thetrapezium) is located on one of the sides, parallel to the arm.

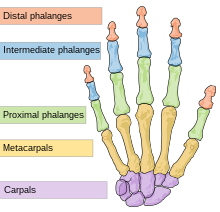

The palm has five bones known as metacarpal bones, one to each of the five digits. Human hands contain fourteen digital bones, also called phalanges, orphalanx bones:two in the thumb (the thumb has no middle phalanx) and three in each of the four fingers. These are the distal phalanx, carrying the nail, the middle phalanx, and the proximal phalanx. Joints are formed wherever two or more of these bones meet. Each of the fingers has three joints:

- metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) – the joint at the base of the finger

- proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) – the joint in the middle of the finger

- distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) – the joint closest to the fingertip.

Sesamoid bonesare smallossifiednodes embedded in the tendons to provide extra leverage and reduce pressure on the underlying tissue. Many exist around the palm at the bases of the digits; the exact number varies between different people.

Thearticulationsare:interphalangeal articulationsbetween phalangeal bones, andmetacarpophalangeal jointsconnecting the phalanges to the metacarpal bones.

Muscles

[edit]Each finger mayflexandextend,abductandadduct,and so alsocircumduct.Flexion is by far the strongest movement. In humans, there are two large muscles that produce flexion of each finger, and additional muscles that augment the movement. The muscle bulks that move each finger may be partly blended, and the tendons may be attached to each other by a net of fibrous tissue, preventing completely free movement. Although each finger seems to move independently, moving one finger also moves the other fingers slightly which is called finger interdependence or finger enslaving.[14][15][16]

Fingers do not contain muscles (other thanarrector pili). Themusclesthat move the finger joints are in thepalmandforearm.The long tendons that deliver motion from the forearm muscles may be observed to move under the skin at the wrist and on the back of the hand.

Muscles of the fingers can be subdivided into extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. The extrinsic muscles are the long flexors and extensors. They are called extrinsic because the muscle belly is located on the forearm.

The fingers have two long flexors, located on the underside of the forearm. They insert by tendons to the phalanges of the fingers. The deep flexor attaches to the distal phalanx, and the superficial flexor attaches to the middle phalanx. The flexors allow for the actual bending of the fingers. The thumb has one long flexor and a short flexor in the thenar muscle group. The human thumb also has other muscles in the thenar group (opponensandabductor brevis muscle), moving the thumb in opposition, making grasping possible.

The extensors are located on the back of the forearm and are connected in a more complex way than the flexors to the dorsum of the fingers. The tendons unite with the interosseous and lumbrical muscles to form the extensorhood mechanism. The primary function of the extensors is to straighten out the digits. The thumb has two extensors in the forearm; the tendons of these form theanatomical snuff box.Also, the index finger and the little finger have an extra extensor, used for instance for pointing. The extensors are situated within six separate compartments. The first compartment contains abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis. The second compartment contains extensors carpi radialis longus and brevis. The third compartment contains extensor pollicis longus. The extensor digitorum indicis and extensor digitorum communis are within the fourth compartment. Extensor digiti minimi is in the fifth, and extensor carpi ulnaris is in the sixth.

The intrinsic muscle groups are thethenarandhypothenarmuscles (thenar referring to the thumb, hypothenar to the small finger), thedorsalandpalmar interossei muscles(between the metacarpal bones) and thelumbrical muscles.The lumbricals arise from thedeep flexor(and are special because they have no bony origin) and insert on the dorsal extensor hood mechanism.

Aside from thegenitals,the fingertips possess the highest concentration oftouch receptorsandthermoreceptorsamong all areas of the human skin,[17]making them extremely sensitive to temperature, pressure, vibration, texture and moisture. A study in 2013 suggested fingers can feel nano-scale wrinkles on a seemingly smooth surface, a level of sensitivity not previously recorded.[18]This makes the fingers commonly used sensory probes to ascertain properties of objects encountered in the world, making them prone toinjury.

Thepulpof a fingeris the fleshy mass on the palmar aspect of the extremity of the finger.[19]

Fingertip wrinkling in water

[edit]Although a common phenomenon, the underlying functions and mechanism of fingertip wrinkling following immersion in water are relatively unexplored. Originally it was assumed that the wrinkles were simply the result of the skin swelling in water,[20]but it is now understood that the furrows are caused by theblood vessels constrictingdue to signalling by thesympathetic nervous systemin response to water exposure.[21][22]One hypothesis for why this occurs, the "rain tread" hypothesis, posits that the wrinkles may help the fingers grip things when wet, possibly being an adaption from a time when humans dealt with rain and dew in forested primate habitats.[21]A 2013 study supporting this hypothesis found that the wrinkled fingertips provided better handling of wet objects but gave no advantage for handling dry objects.[23]However, a 2014 study attempting to reproduce these results was unable to demonstrate any improvement of handling wet objects with wrinkled fingertips.[22]

Regrowth of the fingertips

[edit]Fingertips, after having been torn off children, have been observed to regrow in less than 8 weeks.[24]However, these fingertips do not look the same, although they do look more appealing than a skin graft or a sewn fingertip. No healing occurs if the tear happens below thenail.This works because thedistal phalangesare regenerative in youth, andstem cellsin the nails create new tissue that ends up as the fingertip.[25]

Brain representation

[edit]Each finger has an orderly somatotopic representation on thecerebral cortexin thesomatosensory cortexarea 3b,[26]part of area 1[27]and a distributed, overlapping representations in thesupplementary motor areaandprimary motor area.[28]

The somatosensory cortex representation of the hand is a dynamic reflection of the fingers on the external hand: insyndactylypeople have aclubhandof webbed, shortened fingers. However, not only are the fingers of their hands fused, but the cortical maps of their individual fingers also form a club hand. The fingers can be surgically divided to make a more useful hand. Surgeons did this at the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery in New York to a 32-year-old man with the initials O. G.. They touched O. G.'s fingers before and after surgery while using MRI brain scans. Before the surgery, the fingers mapped onto his brain were fused close together; afterward, the maps of his individual fingers did indeed separate and take the layout corresponding to a normal hand.[29]

Clinical significance

[edit]Anomalies, injuries and diseases

[edit]

A rare anatomical variation affects 1 in 500 humans, in which the individual has more than the usual number of digits; this is known aspolydactyly.A human may also be born without one or more fingers or underdevelopment of some fingers such assymbrachydactyly.Extra fingers can be functional. One individual with seven fingers not only used them but claimed that they "gave him some advantages in playing the piano".[30]

Phalangesare commonly fractured. A damaged tendon can cause significant loss of function in fine motor control, such as with amallet finger.They can be damaged by cold, includingfrostbiteand non-freezing cold injury (NFCI); and heat, includingburns.

The fingers are commonly affected by diseases such asrheumatoid arthritisandgout.Individuals with diabetes often use the fingers to obtain blood samples for regular blood sugar testing.Raynaud's phenomenonandParoxysmal hand hematomaare neurovascular disorders that affect the fingers.

Research has linked theratio of lengths between the index and ring fingersto higher levels oftestosterone,and to variousphysical and behavioral traitssuch as penis length[31]and risk for development ofalcohol dependence[32]orvideo game addiction.[33]

Etymology

[edit]The English wordfingerstems fromOld Englishfinger,ultimately fromProto-Germanic*fingraz('finger'). It iscognatewithGothicfiggrs,Old Norsefingr,orOld High Germanfingar.Linguists generally assume that*fingrazis aro-stem deriving from a previous form*fimfe,ultimately fromProto-Indo-European*pénkʷe('five').[34]

The name pinkie derives from Dutchpinkje,of uncertain origin. In English only the digits on the hand are known as fingers. However, in some languages the translated version of fingers can mean either the digits on the hand or feet. In English a digit on a foot has the distinct name of toe.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^abChambers 1998 p. 603

- ^abcOxford Illustrated pp. 311, 380

- ^Rüdiger Wehner,Walter Gehring:Zoologie.Thieme Verlag Stuttgart/ New York, 1990, pp. 550 and 723-726.

- ^Neil A. Campbell,Jane B. Reece:Biology.Heidelberg/ Berlin 2003, pp. 515-517 and 583.

- ^"It is generally accepted that the precision grip and independent finger movements (IFMs) in monkey and man are controlled by the direct (monosynaptic)corticomotoneuronal (CM) pathway."Sasaki, Shigeto; et, al. (2004)."Dexterous Finger Movements in Primate Without Monosynaptic Corticomotoneuronal Excitation".Journal of Neurophysiology.92(5): 3142–3147.doi:10.1152/jn.00342.2004.PMID15175371.Retrieved6 September2021.

- ^Dominy, Nathaniel J. (2004)."Fruits, Fingers, and Fermentation: The Sensory Cues Available to Foraging Primates".Integrative and Comparative Biology.44(4): 295–303.doi:10.1093/icb/44.4.295.PMID21676713.Retrieved6 September2021.

- ^Yum, S.M.; et, al. (2020)."Fingerprint ridges allow primates to regulate grip".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.117(50): 31665–31673.Bibcode:2020PNAS..11731665Y.doi:10.1073/pnas.2001055117.PMC7749313.PMID33257543.

- ^V. Garcia-Martinez, D. Macias et al:Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation and programmed cell death (apoptosis) in the interdigital tissue of the embryonic chick leg bud.In:Journal of Cell Science.Vol. 6, Issue 1, September 1993, pp. 201-208.

- ^M. A. Fernandez-Teran, J. M. Hurle:Syndactyly induced by Janus Green B in the embryonic chick leg bud: a reexamination.In Development, Volume 8, Issue 1, December 1984, pp. 159–175.

- ^Sajid Malik:Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification.In:European Journal of Human Genetics.Vol. 20, 2012, pp. 817–824.

- ^Tracy L. Kivell; Pierre Lemelin; Brian G. Richmond; Daniel Schmitt (2016).The Evolution of the Primate Hand: Anatomical, Developmental, Functional, and Paleontological Evidence.Springer. pp. 7–.ISBN978-1-4939-3646-5.

- ^Oxford Advanced p. 326

- ^Goebl, W.; Palmer, C. (2013). Balasubramaniam, Ramesh (ed.)."Temporal Control and Hand Movement Efficiency in Skilled Music Performance".PLOS ONE.8(1): e50901.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...850901G.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050901.PMC3536780.PMID23300946.

- ^Li, Z.M.; Latash, M.L.; Zatsiorsky, V.M. (1998). "Force sharing among fingers as a model of the redundancy problem".Experimental Brain Research.119(3): 276–286.doi:10.1007/s002210050343.PMID9551828.S2CID46568801.

- ^Zatsiorsky, V.M.; Latash, M.L.; Li, Z.M. (2000). "Enslaving effects in multi-finger force production".Experimental Brain Research.131(2): 187–195.doi:10.1007/s002219900261.PMID10766271.S2CID23697755.

- ^Abolins, V.; Latash, M.L. (2021). "The Nature of Finger Enslaving: New Results and Their Implications".Motor Control.25(4): 680–703.doi:10.1123/mc.2021-0044.ISSN1087-1640.PMID34530403.S2CID237545122.

- ^Ludovico, Alessandro (2024-01-16).Tactical Publishing: Using Senses, Software, and Archives in the Twenty-First Century.MIT Press.ISBN978-0-262-54205-0.

- ^"Feeling small: Fingers can detect nano-scale wrinkles even on a seemingly smooth surface".Science Daily.September 16, 2013.

- ^medilexicon > Medical Dictionary - 'Pulp Of Finger'Citing: Stedman's Medical Dictionary. 2006

- ^Herlihy, Barbara (2021-04-25).The Human Body in Health and Illness - E-Book: The Human Body in Health and Illness - E-Book.Elsevier Health Sciences.ISBN978-0-323-81123-1.

- ^abChangizi, M.; Weber, R.; Kotecha, R.; Palazzo, J. (2011)."Are Wet-Induced Wrinkled Fingers Primate Rain Treads?".Brain, Behavior and Evolution.77(4): 286–90.doi:10.1159/000328223.PMID21701145.

- ^abHaseleu, Julia; Omerbašić, Damir; Frenzel, Henning; Gross, Manfred; Lewin, Gary R. (2014). Goldreich, Daniel (ed.)."Water-Induced Finger Wrinkles Do Not Affect Touch Acuity or Dexterity in Handling Wet Objects".PLOS ONE.9(1): e84949.Bibcode:2014PLoSO...984949H.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084949.PMC3885627.PMID24416318.

- ^Kareklas, K.; Nettle, D.; Smulders, T. V. (2013)."Water-induced finger wrinkles improve handling of wet objects".Biology Letters.9(2): 20120999.doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0999.PMC3639753.PMID23302867.

- ^Siegel, Jake."Kids can regrow a fingertip. Why can't adults?".University of Washington Newsroom.University of Washington. Archived fromthe originalon 1 November 2021.Retrieved1 November2021.

- ^Doucleff, Michaeleen (12 June 2013)."Chopped: How Amputated Fingertips Sometimes Grow Back".National Public Radio.Retrieved1 November2021.

- ^Van Westen, D; Fransson, P; Olsrud, J; Rosén, B; Lundborg, G; Larsson, EM (2004)."Fingersomatotopy in area 3b: an fMRI-study".BMC Neurosci.5:28.doi:10.1186/1471-2202-5-28.PMC517711.PMID15320953.

- ^Nelson, AJ; Chen, R (2008)."Digit somatotopy within cortical areas of the postcentral gyrus in humans".Cereb Cortex.18(10): 2341–51.doi:10.1093/cercor/bhm257.PMID18245039.

- ^Kleinschmidt, A; Nitschke, MF; Frahm, J (1997). "Somatotopy in the human motor cortex hand area. A high-resolution functional MRI study".Eur J Neurosci.9(10): 2178–86.doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01384.x.PMID9421177.S2CID21042040.

- ^Mogilner, A; Grossman, JA; Ribary, U; Joliot, M; Volkmann, J; Rapaport, D; Beasley, RW; Llinás, RR (1993)."Somatosensory cortical plasticity in adult humans revealed by magnetoencephalography".Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.90(8): 3593–97.Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.3593M.doi:10.1073/pnas.90.8.3593.PMC46347.PMID8386377.

- ^Dwight, T (1892). "Fusion of hands".Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History.4:473–86.

- ^"Penis Size Linked to Length of Fingers".men.webmd.Retrieved24 July2022.

- ^Kornhuber, J; Erhard, G; Lenz, B; Kraus, T; Sperling, W; Bayerlein, K; Biermann, T; Stoessel, C (2011)."Low digit ratio 2D:4D in alcohol dependent patients".PLOS ONE.6(4): e19332.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...619332K.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019332.PMC3081847.PMID21547078.

- ^Kornhuber, J.; Zenses, EM; Lenz, B; Stoessel, C; Bouna-Pyrrou, P; Rehbein, F; Kliem, S; Mößle, T (2013)."Low digit ratio 2D:4D associated with video game addiction".PLOS ONE.8(11): e79539.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879539K.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079539.PMC3827365.PMID24236143.

- ^Kroonen, Guus (2013).Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic.Brill. p. 141.ISBN978-90-04-18340-7.

References

[edit]- The Chambers Dictionary.Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd. 2000 [1998].ISBN0-550-14000-X.

- The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary.Great Britain: Oxford University Press. 1976 [1975].

- Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English.London: Oxford University Press. 1974 [1974].ISBN0-19-431102-3.