Greater Finland

This article includes a list ofgeneral references,butit lacks sufficient correspondinginline citations.(December 2014) |

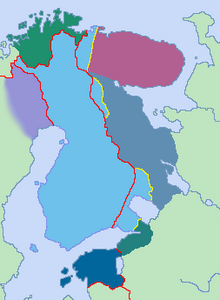

Greater Finland(Finnish:Suur-Suomi;Estonian:Suur-Soome;Swedish:Storfinland) is anirredentistandnationalistidea which aims for the territorial expansion ofFinland.[1]It is associated withPan-Finnicism.The most common concept saw the country as defined bynatural bordersencompassing the territories inhabited byFinnsandKarelians,ranging from theWhite SeatoLake Onegaand along theSvir RiverandNeva River—or, more modestly, theSestra River—to theGulf of Finland.Some extremist proponents also included theKola Peninsula,Finnmark,SwedishMeänmaa,Ingria,andEstonia.[2]

The idea of a Greater Finland rapidly gained popularity afterFinland became independentin December 1917. The idea has lost support afterWorld War II(1939–1945).

Definitions

[edit]The concept of Greater Finland was commonly defined by what was seen asnatural borders,which included the areas inhabited byFinnsandKarelians.This ranged from theWhite SeatoLake Onegaand along theSvir RiverandNeva River.Alternatively, it ranged from theSestra Riverto theGulf of Finland.Some extremists also included theKola PeninsulaandIngriain Russia,Finnmarkin Norway, theTorne Valleyin Sweden, andEstonia.[2]

History

[edit]Natural borders

[edit]The idea of the so-called three-isthmus border—defined by the White Isthmus, theOlonets Isthmus,and theKarelian Isthmus—is hundreds of years old, dating back to the period when Finland was part of Sweden. There was a disagreement between Sweden and Russia as to where the border between the two countries should be. The Swedish government considered a three-isthmus border to be the easiest to defend.

Although the term "Greater Finland" was not used in the early 19th century, the idea of Finland's natural geographical boundaries dates back to then. In 1837, the botanist Johan Ernst Adhemar Wirzén defined Finland's wild plant distribution area as the eastern border lines of theWhite Sea,Lake Onega,and theRiver Svir.[2]The geologistWilhelm Ramsaydefined the bedrock concept ofFenno-Scandinaviain 1898.[2]

Karelianism

[edit]Karelianism was anational romantichobby for artists, writers, and composers in whichKarelianand Karelian-Finnish culture was used as a source of inspiration. Karelianism was most popular in the 1890s. For example, the authorIlmari Kianto,known as the "White friend", wrote about his travels toWhite Kareliain the 1918 bookFinland at Its Largest: For the Liberation of White Karelia.

Other Nordic countries

[edit]TheKvens,a minority inNorthern Norway,helped Finnish settlements spread, especially in the 1860s. TheAcademic Karelia Societyand the Finnish Heritage Association worked actively with the Kvens from 1927 to 1934, and the Finnish media spreadpan-Fennicistpropaganda through various channels. Activity slowed down from 1931 to 1934.

In the early days of its independence, Finland wantedFinnish-speaking areasinNorrbotten,Sweden, to join Finland. This was a reaction to the effort by Finland's ownÅlandto join Sweden. The Finnish government set up a committee to expand Finnish national movements. Sweden, for its part, pushed for instruction in theSwedish languagein its northern Finnish regions. Until the 1950s, many schoolchildren in Norrbotten were banned from using theFinnish languageduring breaks at school.

Heimosodat

[edit]The Greater Finland ideology gained strength from 1918 to 1920, during the Heimosodat, with the goal of combining allFinnic peoplesinto a single state. Similar ideas also spread in westernEast Karelia.TwoRussianmunicipalities,RepolaandPorajärvi,wanted to become part of Finland but could not under the strict conditions of theTreaty of Tartu.They declared themselves independent in 1919, but the border change was never officially confirmed, mainly because of the treaty, which was negotiated the following year. In the Treaty of Tartu negotiations in 1920, Finland demanded more of Eastern Karelia. Russia agreed to this but kept Repola and Porajärvi for itself, offering FinlandPetsamoinstead. PresidentKaarlo Juho Ståhlbergof Finland agreed to the exchange.

Karelians in Uhtua (nowKalevala, Russia) wanted their own state, so they created theRepublic of Uhtua.Ingrian Finnsalso created their own state,North Ingria,but with the intention of being incorporated into Finland. Both states ceased to exist in 1920.

The Greater Finland ideology inspired theAcademic Karelia Society,theLapua movement,and that movement's successor, thePatriotic People's Movement.TheMannerheimSword Scabbard Declarationsin 1918 and 1941 increased enthusiasm for the idea.

1920s and 1930s

[edit]

Under theTreaty of Tartu,Soviet Russia agreed to give Eastern Karelia (known simply as Karelia in the laterSoviet Union) political autonomy as a concession to Finnish sentiment. This was in line with theBolshevikleadership's policy at the time of offering political autonomy to each of the national minorities within the new Soviet state. At the same time, theLeague of Nationssolved theÅland crisisin Finland's favor.

After theFinnish Civil Warin 1918, theRed Guardsfled to Russia and rose to a leading position in Eastern Karelia. Led byEdvard Gylling,they helped establish the Karelian Workers' Commune. The Reds were also assigned to act as abridgeheadin the Finnish revolution. Finnish politicians in Karelia strengthened their base in 1923 with the establishment of theKarelian ASSR.Finnish nationalists helped some Karelians who were unhappy with the failure of the Karelian independence movement to organize anuprising,but it was unsuccessful, and a small number of Karelians fled to Finland.

After the civil war, a large number ofleft-wingFinnishrefugeesfled for the Karelian ASSR. These Finns—an urbanized, educated, and Bolshevik elite—tended to monopolize leadership positions within the new republic. The "Finnishness" of the area was enhanced by some migration ofIngrian Finns,and by theGreat Depression.Gylling encouraged Finns inNorth Americato flee to the Karelian ASSR, which was held up as a beacon of enlightened Soviet national policy and economic development.

Even by 1926, 96.6% of the population of the Karelian ASSR spokeKarelianas their mother tongue. No unified Karelianliterary languageexisted, and the prospect of creating one was considered problematic because of the language's many dialects. The local Finnish leadership had a dim view of the potential of Karelian as a literary language and did not try to develop it. Gylling and the Red Finns may have considered Karelian to be a mere dialect of Finnish. They may also have hoped that, through the adoption of Finnish, they could unify Karelians and Finns into one Finnic people. All education of Karelians was conducted in Finnish, and all publications became Finnish (with the exception of some inRussian).

By contrast, the Karelians ofTver Oblast,who had gained a measure of political autonomy independent of Finnish influence, were able by 1931 to develop a literary Karelian based on theLatin Alpha bet.These Tver Karelians became hostile to what they saw as Finnish dominance of Karelia, as did some of the small, local Karelianintelligentsia.Reactions to the use of Finnish among the Karelians themselves were diverse. Some had difficulty understanding written Finnish. There was outright resistance to the language from residents ofOlonets Karelia,while White Karelians had a more positive attitude toward it.

In the summer of 1930, "Finnification politics" became politically sensitive. TheLeningradparty apparatus (the powerful southern neighbor of the Karelian Red Finns) began to protest Finnishchauvinismtoward the Karelians in concert with the Tver Karelians. This coincided with increasing centralization underJoseph Stalinand the concurrent decline in power of many local minority elites. Gylling andKustaa Roviotried to expand the usage of Karelian in certain spheres, but this process was hardly begun before they were deposed. The academic Dmitri Bubrikh then developed a literary Karelian based on theCyrillic Alpha bet,borrowing heavily from Russian.

The Central Committee of the Council of Nationalities and theSoviet Academy of Sciencesprotested the forced Finnification of Soviet Karelia. Bubrikh's Karelian language was adopted from 1937 to 1939, and Finnish was repressed. But the new language, based on an unfamiliar Alpha bet and with extensive usage of Russian vocabulary andgrammar,was difficult for many Karelians to comprehend. By 1939, Bubrikh himself had been repressed, and all forms of Karelian were dropped in both the Karelian ASSR and Tver Oblast (where the Karelian National District was dissolved entirely).[3]

The Great Purge

[edit]In Stalin's Great Purge in 1937, the remaining Red Finns in Soviet Karelia were accused ofTrotskyist-bourgeoisnationalism and purged entirely from the leadership of the Karelian ASSR. Most Finns in the area were executed or forcefully transferred to other parts of the Soviet Union.[4]During this period, no official usage of Karelian was pursued, and the use of the Finnish language was repressed, relegating it to an extremely marginal role, making Russian thede factoofficial languageof the republic.[5]By this time, the economic development of the area had also attracted a growing number of internal migrants from other areas of the Soviet Union, who steadily diluted the "national" character of the Karelian ASSR.

TheKarelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic(KFSSR) was founded by the Soviet Union at the beginning of theWinter War,and was led by theTerijoki governmentandOtto Wille Kuusinen.This new entity was created with an eye to absorbing a defeated Finland into one greater Finnic (and Soviet) state, and so the official language returned to Finnish. However, the Soviet military was unable to completely defeat Finland, and this idea came to nothing. Despite this, the KFSSR was maintained as a fullUnion Republic(on a par withUkraineorKazakhstan,for example) until the end of theStalinist period,and Finnish was at least nominally an official language until 1956. The territory Finland was forced to cede under theMoscow Peace Treatywas incorporated partly into the KFSSR, but also intoLeningrad Oblastto the south andMurmansk Oblastto the north.

During theContinuation Warfrom 1941 to 1944, about 62,000 Ingrian Finns escaped to Finland from German-occupied areas, of whom 55,000 were returned to the Soviet Union and expelled toSiberia.Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, they were permitted to settle within the KFSSR, although not inIngriaitself.[6]

Continuation War

[edit]

During the civil war in 1918, when the military leaderCarl Gustaf Emil Mannerheimwas inAntrea,he issued one of his famousSword Scabbard Declarations,in which he said that he would not "sheath my sword before law and order reigns in the land, before all fortresses are in our hands, before the last soldier ofLeninis driven not only away from Finland, but fromWhite Kareliaas well ".[7]During the Continuation War, Mannerheim gave the second Sword Scabbard Declaration. In it, he mentioned "the Great Finland", which brought negative attention in political circles.

During the Continuation War, Finland occupied the most comprehensive area in its history. Many people elsewhere, as well as Finland'sright-wingpoliticians, wanted to annex East Karelia to Finland. The grounds were not only ideological and political but also military, as the so-called three-isthmus line were considered easier to defend. On 20 July 1941, a celebration was held inVuokkiniemi,whereWhiteandOlonets Kareliawere declared to have joined Finland.[8]

Russians and Karelians were treated differently in Finland, and the ethnic background of the country's Russian-speaking minority was studied to determine which of them were Karelian (i.e., "the national minority" ) and which were mostly Russian (i.e., "the un-national minority" ). The Russian minority were taken toconcentration campsso that they would be easier to move away.

In 1941, the government published aGermanedition ofFinnlands Lebensraum,a book supporting the idea of Greater Finland, with the intention of anne xing Eastern Karelia and Ingria.[9]

Finland's eastern question

[edit]During the Continuation War's attack phase in 1941, when the Finns hoped for a German victory over the Soviet Union, Finland began to consider what areas it could get in a possible peace treaty with the Soviets. The German objective was to take over theArkhangelsk–Astrakhanline, which would have allowed Finland to expand to the east. A 1941 book by professorJalmari Jaakkola,titledDie Ostfrage Finnlands,sought to justify the occupation of East Karelia. The book was translated intoEnglish,Finnish, andFrench,and received criticism from Sweden and theUnited States.

The Finnish Ministry of Education established the Scientific Committee of East Karelia on 11 December 1941 to guide research in East Karelia. The first chairman of the commission was the rector of theUniversity of Helsinki,Kaarlo Linkola,and the second chairman wasVäinö Auer.Jurists worked to prepare international legal arguments for why Finland should get East Karelia.

Motivations

[edit]The rationales of the Greater Finland idea are a subject of disagreement. Some supported the idea out of a desire for wider cultural cooperation. Later, however, the ideology gained clearerimperialistcharacteristics. The main supporter of the idea, theAcademic Karelia Society,was born as a cultural organization, but in its second year, it released a program that dealt with broader strategic, geographical, historical, and political arguments for Greater Finland.

The idea today

[edit]The Greater Finland idea is unpopular today, with those who wish for Finnish territorial expansion, such as the formerFinns Party Youthand some others wishing for there-annexation of Finnish Kareliainstead.[10]

See also

[edit]- Finnic countries

- Greater Netherlands

- Greater Romania

- Karelian question

- Pan-Germanism

- Rattachism

- Scandinavism

References

[edit]- ^Kinnunen, Tiina; Kivimäki, Ville (25 November 2011).Finland in World War II: History, Memory, Interpretations.BRILL. p. 385.ISBN978-90-04-20894-0.

- ^abcdWeiss, Holger (10 August 2020).Locating the Global: Spaces, Networks and Interactions from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century.Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 367.ISBN978-3-11-067071-4.

- ^Rol' D. V. Bubrikha v sozdanii yedinogo karel'skogo yazykaРоль Д. В. Бубриха в создании единого карельского языка[The role of D. V. Bubrikh in the creation of a unified Karelian language]. Бубриховские чтения: гуманитарные науки на Европейском Севере (in Russian). 2015. pp. 259–266.

- ^Kostiainen, Auvo (23 June 2008). "Genocide in soviet Karelia: Stalin's terror and the Finns of soviet Karelia".Scandinavian Journal of History.21(4): 331–342.doi:10.1080/03468759608579334.

- ^Austin, Paul M. (1992)."Soviet Karelian: The Language that Failed".Slavic Review.51(1): 16–35.doi:10.2307/2500259.JSTOR2500259.S2CID159644993.

- ^"Inkerin historia"[History of Inger] (in Finnish). Archived fromthe originalon 16 February 2015.

- ^heninen.net'stranslation of the first Sword Scabbard Declaration.

- ^Roselius, Aapo; Silvennoinen, Oula (2019).Villi itä: Suomen heimosodat ja Itä-Euroopan murros 1918-1921.Helsinki: Tammi. pp. 291–292, 326–327.ISBN978-951-31-7549-8.

- ^Hjelm & Maude 2021,p. 131.

- ^"Tiedusteluyhtiö Stratforin hurja ennuste: Karjala haluaa liittyä Suomeen".iltalehti.fi(in Finnish).Retrieved2024-02-23.

Sources

[edit]- Hjelm, Titus; Maude, George (15 August 2021).Historical Dictionary of Finland.Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 130–131.ISBN978-1-5381-1154-3.

- Manninen, Ohto (1980).Suur-Suomen ääriviivat: Kysymys tulevaisuudesta ja turvallisuudesta Suomen Saksan-politiikassa 1941[Outlines of Greater Finland: The question of the future and security in Finland's German policy in 1941] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kirjayhtymä.ISBN951-26-1735-8.

- Nygård, Toivo (1978).Suur-Suomi vai lähiheimolaisten auttaminen: Aatteellinen heimotyö itsenäisessä Suomessa[Greater Finland or helping neighboring tribes: Ideological tribal work in independent Finland] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Otava.ISBN951-1-04963-1.

- Tarkka, Jukka (1987).Ei Stalin eikä Hitler - Suomen turvallisuuspolitiikka toisen maailmansodan aikana[Neither Stalin nor Hitler - Finland's security policy during the Second World War] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Otava.ISBN951-1-09751-2.

- Seppälä, Helge (1989).Suomi miehittäjänä 1941-1944[Finland as occupier 1941-1944] (in Finnish). Helsinki: SN-kirjat.ISBN951-615-709-2.

- Morozov, K.A. (1975).Karjala Toisen Maailmansodan aikana 1941-1945[Karelia during the Second World War 1941-1945] (in Finnish). Petrozavodsk.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jaakkola, Jalmari (1942).Die Ostfrage Finnlands(in German). WSOY.

- Näre, Sari; Kirves, Jenni (2014).Luvattu maa: Suur-Suomen unelma ja unohdus[Promised land: Greater Finland's dream and oblivion] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Johnny Kniga.ISBN978-951-0-40295-5.

- Trifonova, Anastassija.Suur-Suomen aate ja Itä-Karjala[The idea of Greater Finland and Eastern Karelia](PDF)(in Finnish).University of Tartu,Department of Baltic Finnic Languages. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2016-03-04.

- Solomeštš, Ilja."Ulkoinen uhka keskustan ja periferian suhteissa: Karjalan kysymys pohjoismaisessa vertailussa 1860–1940"[External threat in center-periphery relations: The question of Karelia in a Nordic comparison 1860–1940].Carelia(in Finnish). No. 10–1998. pp. 117–119. Archived fromthe originalon 2006-10-11.

- Ryymin, Teemu (1998).Finske nasjonalisters og norske myndigheters kvenpolitikk i mellomkrigstiden[Finnish nationalists' and Norwegian authorities' women's policy in the interwar period.] (in Norwegian).University of Bergen.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Web version - Olsson, Claes.Suur-Suomen muisto[The memory of Greater Finland] (in Finnish). Archived fromthe originalon 2001-03-06.

- Sundqvist, Janne (26 May 2014).Suur-Suomi olisi onnistunut vain natsi-Saksan avulla[Greater Finland would have succeeded only with the help of Nazi Germany] (in Finnish)..Yle uutiset 26.5.2014.