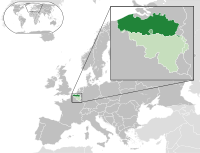

Flemish literature

Flemish literatureisliteraturefromFlanders,historically a region comprising parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. Until the early 19th century, this literature was regarded as an integral part of Dutch literature. After Belgium became independent from the Netherlands in 1830, the term Flemish literature acquired a narrower meaning and refers to the Dutch-language literature produced in Belgium. It remains a part ofDutch-language literature.

Medieval Flemish literature

[edit]In the earliest stages of the Dutch language, a considerable degree of mutual intelligibility with some (what we now call)Germandialects was present, and some fragments and authors are claimed for both realms. Examples include the 12th-centurypoetHendrik van Veldeke,who is claimed by both Dutch andGerman literature.

In the first stages of Flemish literature, poetry was the predominant form of literary expression. In theLow Countriesas in the rest of Europe,courtly romanceandpoetrywere populargenresduring theMiddle Ages.One suchMinnesangerwas the aforementioned Van Veldeke. Thechivalricepicwas a popular genre as well, often featuringKing ArthurorCharlemagne(Karel) asprotagonist(with notable example ofKarel ende Elegast,Dutch for "Charlemagne and the elf-spirit/elf-guest" ).

The first Dutch language writer known by name is the 12th-centuryCounty of LoonpoetHendrik van Veldeke,an early contemporary ofWalther von der Vogelweide.Van Veldeke wrote courtly love poetry, ahagiographyofSaint Servatiusand an epic retelling of theAeneidin aLimburgishdialect that straddles the Dutch-German language boundary.

A number of the survivingepicworks, especially the courtly romances, were copies from or expansions of earlier German orFrenchefforts, but there are examples of truly original works (such as the anonymously writtenKarel ende Elegast) and original Dutch-language works that were translated into other languages (notable Dutch morality playElckerlijcformed the basis for the English playEveryman).

Apart from ancient tales embedded in Dutchfolk songs,virtually no genuinefolk-talesof Dutch antiquity have come down to us, and scarcely any echoes ofGermanic myth.On the other hand, thesagasof Charlemagne and Arthur appear immediately inMiddle Dutchforms. These were evidently introduced by wanderingminstrelsand translated to gratify the curiosity of the noble women. It is rarely that the name of such a translator has reached us. TheChanson de Rolandwas translated somewhere in the twelfth century, and theFlemishminstrelDiederic van Assenedecompleted his version ofFloris and BlancheflourasFloris ende Blancefloeraround 1260.

TheArthurian legendsappear to have been brought to Flanders by some Flemish colonists inWales,on their return to their mother country. Around 1250 aBrabantineminstrel translated theProse Lancelotat the command of hisliege,Lodewijk van Velthem. This adaptation, known as theLancelot Compilation,contains many differences from the French original, and includes a number of episodes that were probably originally separate romances. Some of these are themselves translations of French originals, but others, such as theMoriaen,seem to be originals. TheGauvainwas translated byPennincandPieter VostaertasRoman van Waleweinbefore 1260, while the first wholly original Dutch epic writer,Jacob van Maerlant,occupied himself around 1260 with several romances dealing withMerlinand theHoly Grail.

The earliest existing fragments of the epic ofReynard the Foxwere written inLatinby Flemishpriests,and about 1250 the first part of a very important version in Dutch,Van den vos Reynaerde( "Of Reynard" ) was made byWillem.In his existing work the author followsPierre de Saint-Cloud,but not slavishly; and he is the first really admirable writer that we meet with in Dutch literature. The second part was added by another poet, Aernout, of whom we know little else either.

The first lyrical writer of the Low Countries wasJohn I, Duke of Brabant,who practised theminneliedwith success. In 1544 the earliest collection of Dutch folk-songs saw the light, and in this volume one or two romances of the fourteenth century are preserved, of which "Het Daghet in den Oosten" is the best known.

Up until now, theMiddle Dutch languageoutput mainly serviced the aristocratic and monastic orders, recording the traditions of chivalry and of religion, but scarcely addressed the bulk of the population. With the close of the thirteenth century a change came over the face of Dutch literature.

The founder and creator of this original Dutch literature wasJacob van Maerlant.HisDer Naturen Bloeme( "The Flower of Nature" ), written about 1263, takes an important place in early Dutch literature. It is a collection ofmoralandsatiricaladdresses to all classes of society. With hisRijmbijbel( "Verse Bible" ) he foreshadowed the courage and free-thought of theReformation.It was not until 1284 that he began hismasterpiece,De Spieghel Historiael( "The Mirror of History" ) at the command of Count Floris V.

From the very first the literary spirit in the Low Countries began to assert itself in a homely and utilitarian spirit. Thoroughly aristocratic in feeling wasHem van Aken,apriestofLouvain,who lived about 1255–1330, and who combined to a very curious extent the romantic and didactic elements prevailing at the time. As early as 1280 he had completed his translation of theRoman de la Rose,which he must have commenced in the lifetime of its authorJean de Meung.

As forprose,the oldest pieces of Dutch prose now in existence arechartersof towns in Flanders andZeeland,dated 1249, 1251 and 1254.Beatrice of Nazareth(1200–1268) was the first known prose writer in the Dutch language, the author of the notable dissertation known as theSeven Ways of Holy Love.From the other Dutchmysticswhose writings have reached us, the BrusselsfriarJan van Ruusbroec (better known in English as theBlessedJohn of Ruysbroeck,1293/4–1381), the "father of Dutch prose" stands out. A prosetranslationof theOld Testamentwas made about 1300, and there exists aLife of Jesusof around the same date.

The poets of the Low Countries had already discovered in late medieval times the value ofguildsin promoting theartsand industrialhandicrafts.The term "Collèges de Rhétorique" ( "Chambers of Rhetoric") is supposed to have been introduced around 1440 to thecourtiersof theBurgundiandynasty, but the institutions themselves existed long before. These literary guilds, whose members called themselves "Rederijkers" or "Rhetoricians", lasted until the end of the sixteenth century and during the greater part of that time preserved a completely medieval character, even when the influences of theRenaissanceand the Reformation obliged them to modify in some degree their outward forms. They were in almost all cases absolutelymiddle classin tone, and opposed toaristocraticideas and tendencies in thought.

Of these chambers, the earliest were almost entirely engaged in preparingmysteriesandmiracle playsfor the people. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, theGhentchamber began to exercise a sovereign power over the otherFlemishchambers, which was emulated later on inHollandby the Eglantine at Amsterdam. But this official recognition proved of no consequence inliteratureand it was not in Ghent but inAntwerpthat intellectual life first began to stir. In Holland theburghersonly formed the chambers, while in Flanders the representatives of thenoblefamilies were honorary members, and assisted with their money at the arrangement ofecclesiasticalorpoliticalpageants.Their Landjuwelen, or Tournaments of Rhetoric, at which rich prizes were awarded, were the occasions upon which the members of the chambers distinguished themselves.

Between 1426 and 1620, at least 66 of these festivals were held. The grandest of all was the festival celebrated at Antwerp on August 3, 1561. TheBrusselschamber sent 340 members, all on horseback and clad incrimsonmantles. The town of Antwerp gave a ton of gold to be given in prizes, which were shared among 1,893 rhetoricians. This was the zenith of the splendour of the chambers, and after this time they soon fell into disfavour.

Theirdramatic piecesproduced by the chambers were of a didactic cast, with a strong farcical flavour, and continued the tradition of Jacob van Maerlant and his school. They very rarely dealt withhistoricalor even Biblical personages, but entirely with allegorical and moral abstractions. The most notable examples of Rederijker theatre includeMariken van Nieumeghen( "Mary ofNijmegen") andElckerlijc(which was translated intoEnglishasEveryman).

Of the purefarcesof the rhetorical chambers we can speak with still more confidence, for some of them have come down to us, and among the authors famed for their skill in this sort of writing are namedCornelis EveraertofBrugesandLaurens JanssenofHaarlem.The material of these farces is extremely raw, consisting of roughjestsat the expense ofpriestsand foolish husbands, silly old men and their light wives.

The chambers also encouraged the composition of songs, but with very little success; they produced nolyricalgenius more considerable thanMatthijs de Casteleyn(1488–1550) ofOudenaarde,author ofDe Conste van Rhetorijcken( "The Art of Rhetoric" ).

The first writer who used the Dutch tongue with grace and precision of style was a woman and a professed opponent ofLutheranismandreformed thought.Modern Dutch literature practically begins withAnna Bijns(c. 1494–1575). Bijns, who is believed to have been born at Antwerp in 1494, was aschoolmistressat that city in hermiddle life,and inold ageshe still instructed youth in theCatholic religion.She died on April 10, 1575. From her work we know that she was alaynun and that she occupied a position of honour and influence in Antwerp. Bijns' main subjects werefaithand the character ofLuther.In her first volume of poetry (1528) the Lutherans are scarcely mentioned and the focus is on her personal experience of faith. In the volume of poetry of 1538 every page is occupied withinvectiveagainst the Lutherans. All the poems of Anna Bijns still extant are of the form calledrefereinen(refrains). Her mastery over verse form is considered to be remarkable. With the writings of Anna Bijns, the period of Middle Dutch closes andmodern Dutchbegins.

Split between North and South

[edit]Flanders formed a political and cultural whole with the Netherlands until 1579, when as a result of theReformationtheProtestantnorthern provinces (part of today'sNetherlands) split off from theRoman-Catholicsouth which remained under Spanish rule.

While theRepublic of the Seven United Netherlandswitnessed itsGolden Age,theSouthern Netherlandssuffered war and misery underSpanish occupation.As theProtestantsfled from theCatholicSouthern Netherlands,the once prospering port town ofAntwerpstarted to decline as a metropolis and this to the benefit of towns and cities in the Netherlands, likeAmsterdam,The Hague,RotterdamandUtrecht.As a result of these political developments, the literature in the South, Flanders andBrabantchanged its character. The flowering of medieval literature came to an abrupt end while in the 17th century the North knew a 'Golden Age' in the arts including literature. With the mass exodus of Flemish intellectuals to the Dutch Republic, literary activity in Flanders virtually came to a halt. In the French occupied part of Flanders a few major figures were active includingDominic De Jonghe(1654–1717) who translated Le Cid byPierre Corneilleinto Dutch, the poetMichiel de Swaen(1654–1707) who wrote the epicHet Leven en Dood van Jezus Christus(The Life and Death of Jesus Christ) (1694) and the comedyThe gecroonde leerse(The Crowned Boot) andWillem Ogierwho is known for the comedyDroncken Heyn(Drunk Heyn) (1639) and a drama series entitledDe seven hooft-sonden(The Seven Capital Sins) (1682).

During the 18th century, Flemish literary production was at a low tide. In 1761Jan Des Rocheswho was born inThe Haguepublished theNieuwe Nederduytsche spraek-konst,a Dutch grammar that attempted to challenge the use of Latin as a culture language and French as the language of prestige by elaborating a standardized southern Dutch (Flemish) language. The Brussels lawyerJan-Baptist Verlooy(1746–1797) wrote theVerhandeling op d'onacht der moederlyke tael in de Nederlanden(Treatise on the negligence of the mother tongue in the Netherlands) (1788), a report on the status of the Dutch language and the contempt with which it was treated in the past.

Other important authors includeWillem Verhoeven(1738–1809),Charles Broeckaert(1767–1826) (author of the Flemish popular novelJelle en Mietje), andJan-Baptist Hofman(1758–1835), author of middle class tragedies.

Reunification and new split

[edit]After the conclusion of theNapoleonic Wars,Belgium and the Netherlands were reunited in 1815 under Dutch rule as theUnited Kingdom of the Netherlands.The reunification lead to a wider recognition of the Dutch language in Belgium. Resentment of Dutch rule by the French-speaking elites and the Catholic Church created a climate in which the Belgians revolted against Dutch rule in 1830, an event which is known as theBelgian Revolution.

The immediate result of the Belgian Revolution was a reaction against everything associated with the Dutch, and a disposition to regard the French language as the speech of liberty and independence. The provisional government of 1830 suppressed the official use of theDutch language,which was relegated to the rank of apatois.[1]

For some years before 1830Jan Frans Willems(1793–1846) had been advocating the use of the Dutch language. He had done his best to allay the frictions between theNetherlandsand Belgium and to prevent a separation. As archivist ofAntwerphe had access to direct sources that allowed him to write a history of Flemish literature. After the revolution his Dutch sympathies made it necessary for him to keep a low profile for a while, but in 1835 he settled inGhent,and devoted himself to the cultivation of the Dutch language. He edited old Flemish classics, such asReinaert de Vos(1836), the rhymingChronicles ofJan van HeeluandJean Leclerc,etc. He gathered around him a group of people such as the chevalierPhilip Blommaert(1809–1871),Karel Lodewijk Ledeganck(1805–1847),Frans Rens(1805–1874),Ferdinand Augustijn Snellaert(1809–1872),Prudens van Duyse(1804–1859), and others who wanted to support the use of the Dutch language.[1]

Philipp Blommaert, who was born in Ghent on 27 August 1809, founded in 1834 in his native town theNederduitsche letteroefeningen,a review for new writers. This magazine was speedily followed by other Flemish organs, and by literary societies for the promotion of Dutch in Flanders. In 1851 a central organization for the Flemish propaganda was provided by a society, named after the father of the movement, theWillemsfonds.TheRoman CatholicFlemings founded in 1874 a rivalDavidsfonds,called after the energeticJean-Baptist David(1801–1866), professor at theUniversite Catholique de Louvain(Leuven), and the author of a Dutch history book on Belgium (Vaderlandsche historie,Louvain, 1842–1866). As a result of this propaganda the Dutch language was placed on an equality with French in law, and in administration, in 1873 and 1878, and in the schools in 1883. Finally in 1886 a Flemish Academy was established by royal authority at Ghent, where a course in Flemish literature had been established as early as 1854.[1]

The claims put forward by the Flemish school were justified by the appearance (1837) ofIn 't Wonderjaer 1566(In the Wonderful year) ofHendrik Conscience,who roused national enthusiasm by describing the heroic struggles of the Flemings against the Spaniards. Conscience was eventually to make his greatest successes in the description of contemporary Flemish life, but his historical romances and his popular history of Flanders helped to give a popular basis to a movement which had been started by professors and scholars.[1]

The first poet of the new school wasKarel Lodewijk Ledeganck,the best known of whose poems are those on the three sister cities ofBruges,Ghent andAntwerp(De drie zustersteden, vaderlandsche trilogie,Ghent, 1846), in which he makes an impassioned protest against the adoption of French ideas, manners and language, and the neglect of Flemish tradition. The book speedily took its place as a Flemish classic. Ledeganck, who was a magistrate, also translated the French code into Dutch.Jan Theodoor van Rijswijck(1811–1849), after serving as a volunteer in the campaign of 1830, settled down as a clerk in Antwerp, and became one of the hottest champions of the Flemish movement. He wrote a series of political and satirical songs, admirably suited to his public. The romantic and sentimental poet,Jan van Beers,was typically Flemish in his sincere and moral outlook on life.Prudens van Duyse,whose most ambitious work was the epicArtevelde(1859), is perhaps best remembered by a collection (1844) of poems for children.Peter Frans Van Kerckhoven(1818–1857), a native of Antwerp, wrote novels, poems, dramas, and a work on the Flemish revival (De Vlaemsche Beweging,1847).[1]

Antwerp produced a realistic novelist inJan Lambrecht Domien Sleeckx(1818–1901). An inspector of schools by profession, he was an indefatigable journalist and literary critic. He was one of the founders in 1844 of theVlaemsch Belgie,the first daily paper in the Flemish interest. His works include a long list of plays, among themJan Steen(1852), a comedy;Gretry,which gained a national prize in 1861;Vissers van Blankenberge(1863); and the patriotic drama ofZannekin(1865). His talent as a novelist was diametrically opposed to the idealism of Conscience. He was precise, sober and concrete in his methods, relying for his effect on the accumulation of carefully observed detail. He was particularly successful in describing the life of the shipping quarter of his native town. Among his novels are:In't Schipperskwartier(1856),Dirk Meyer(1860),Tybaerts en Cie(1867),Kunst en Liefde(Art and Love, 1870), andVesalius in Spanje(1895). His complete works were collected in 17 volumes (1877–1884).[1]

Jan Renier Snieders(1812–1888) wrote novels dealing with North Brabant; his brother,August Snieders(1825–1904), began by writing historical novels in the manner of Conscience, but his later novels are satires of contemporary society. A more original talent was displayed byAnton Bergmann(1835–1874), who, under the pseudonym of Tony, wroteErnest Staas, Advocaat,which gained the quennial prize of literature in 1874. In the same year appeared theNovellenof the sistersRosalie(1834–1875) andVirginie Loveling(1836–1923). These simple and touching stories were followed by a second collection in 1876. The sisters had published a volume of poems in 1870. Virginie Lovelings gifts of fine and exact observation soon placed her in the front rank of Flemish novelists. Her political sketches,In onze Vlaamsche gewesten(1877), were published under the name of W. G. E. Walter.Sophie(1885),Een dure Eed(1892), andHet Land der Verbeelding(1896) are among the more famous of her later works.Reimond Stijns(1850–1905) andIsidoor Teirlinck(1851–1934) produced in collaboration one very popular novel,Arm Vlaanderen(1884), and some others, and have since written separately.Cyriel Buysse,a nephew of Virginie Loveling, is a disciple ofÉmile Zola.Het Recht van den Sterkste(The Right of the Strongest, 1893) is a picture of vagabond life in Flanders;Schoppenboer(The Knave of Spades, 1898) deals with brutalized peasant life; andSursum corda(1895) describes the narrowness and religiosity of village life.[1]

In poetry,Julius de Geyter(1830–1905), author of a rhymed translation of Reinaert (1874), an epic poem on Charles V (1888), etc. produced a social epic in three parts,Drie menschen van in de wieg tot in het graf(Three Men from the Cradle to the Grave, 1861), in which he propounded radical and humanitarian views. The songs ofJulius Vuylsteke(1836–1903) are full of liberal and patriotic ardour; but his later life was devoted to politics rather than literature. He had been the leading spirit of a students association at Ghent for the propagation of Flemish views, and the Willemsfonds owed much of its success to his energetic co-operation. HisUit het studentenlevenappeared in 1868, and his poems were collected in 1881. The poems of Mme van Ackere (1803–1884), néeMaria Doolaeghe,were modelled on Dutch originals.Joanna Courtmans(1811–1890), née Berchmans, owed her fame rather to her tales than her poems; she was above all a moralist and her fifty tales are sermons on economy and the practical virtues. Other poets wereEmmanuel Hiel,author of comedies, opera libretti and some admirable songs; the abbotGuido Gezelle,who wrote religious and patriotic poems in the dialect of West Flanders;Lodewijk de Koninck(1838–1924), who attempted a great epic subject inMenschdom Verlost(1872);Johan Michiel Dautzenberg(1808–1869) fromHeerlen,author of a volume of charmingVolksliederen.The best of Dautzenberg's work is contained in the posthumous volume of 1869, published by his son-in-law,Frans de Cort(1834–1878), who was himself a songwriter, and translated songs fromRobert Burns,fromJacques Jasminand from German. TheMakamen en Ghazelen(1866), adapted fromRückert's version of Hariri, and other volumes byJan Ferguut(J. A. van Droogenbroeck, 1835–1902) show a growing preoccupation with form, and with the work ofGentil Theodoor Antheunis(1840–1907), they prepare the way for the ingenious and careful workmanship of the younger school of poets, of whomCharles Polydore de Montwas the leader. He was born at Wambeke in Brabant in 1857, and became professor in the academy of the fine arts at Antwerp. He introduced something of the ideas and methods of contemporary French writers into Flemish verse; and explained his theories in 1898 in an Inleiding tot de Poezie. AmongPol de Mont's numerous volumes of verse dating from 1877 onwards areClaribella(1893), andIris(1894), which contains amongst other things a curiousUit de Legende van Jeschoea-ben-Josief,a version of the gospel story from a Jewish peasant.[2]

Mention should also be made of the history of Ghent (Gent van den vroegsten Tijd tot heden, 1882-1889) byFrans de Potter(1834–1904), and of the art criticisms ofMax Rooses(1839–1914), curator of thePlantin-Moretus Museumin Antwerp, and ofJulius Sabbe(1846–1910).[3]

20th century

[edit]

In the twentieth Century Flemish literature evolved further and was influenced by the international literary evolution.Cyriel BuysseandStijn Streuvelswere influenced by thenaturalistliterary fashion, whileFelix Timmermanswas aneo-romanticist.

AfterWorld War Ithe poetPaul van Ostaijenwas an important representative ofexpressionismin his poems. In betweenWorld War IandWorld War II,Gerard Walschap,Willem ElsschotandMarnix Gijsenwere prominent Flemish writers. After World War II the firstavant-gardemagazineTijd en Mens(E: Time and People) was published from 1949 up to 1955. In 1955 it was succeeded byGard Sivik(E: Civil Guard) (up to 1964), withHugues C. PernathandPaul Snoek.The most prominent FlemishVijftiger(E: Generation fifties) wasHugo Claus,who plays an important role in Flemish literature since then. Other postwar poets wereAnton van WilderodeandChristine D'Haen.Some of the writers who made their debut after 1960 areEddy Van Vliet,Herman de Coninck,Roland Jooris,Patrick Conrad andLuuk Gruwez.

The renewal of the Flemish prose immediately after World War II was the work of Hugo Claus andLouis Paul Boon.Johan DaisneandHubert Lampointroducedmagic realismin Flemish literature.Ivo MichielsandPaul De Wispelaererepresented thenew novel.In the eightiesWalter van den BroeckandMonika van Paemelcontinued to write in the style of Louis Paul Boon.

Other contemporary authors areWard RuyslinckandJef Geeraerts,Patrick Conrad,Kristien Hemmerechts,Eric de Kuyper,Stefan Hertmans,Pol Hoste,Paul Claes,Jan Lauwereyns,Anne ProvoostandJos Vandeloo.In the nineties theGeneration X,withHerman BrusselmansandTom Lanoyemade their debut on the Flemish literary scene.

Overview

[edit]- Johan Anthierens(1937–2000)

- Pieter Aspe(Pierre Aspeslag, 1953–2021)

- Aster Berkhof(Lode Van Den Bergh, born 1920)

- Louis Paul Boon(1912–1979)

- Herman Brusselmans(born 1957)

- Libera Carlier(1926–2007)

- Ernest Claes(1885–1968)

- Paul Claes(born 1943)

- Hugo Claus(1929–2008)

- Patrick Conrad(born 1945)

- Johan Daisne(Herman Thiery, 1912–1978)

- Herman De Coninck(1944–1997)

- Saskia de Coster(born 1976)

- Filip De Pillecyn(1891–1962)

- Rita Demeester(1946–1993)

- Willem Elsschot(1882–1960)

- Fritz Francken(1893–1969)

- Marnix Gijsen(1899–1984)

- Maurice Gilliams(1900–1982)

- Luuk Gruwez(born 1953)

- Kristien Hemmerechts(born 1955)

- Stefan Hertmans(born 1951)

- Karel Jonckheere(1906–1993)

- Paul Kenis(1885–1934)

- Eric de Kuyper(born 1942)

- Hubert Lampo(1920–2006)

- Tom Lanoye(born 1958)

- Jan Lauwereyns(born 1969)

- Maurice Maeterlinck(1862–1949)

- Tom Naegels(born 1975)

- Alice Nahon(1896–1933)

- Leo Pleysier(born 1945)

- Anne Provoost(born 1964)

- Jean Ray(John Flanders) (1887–1964)

- Willem Roggeman(born 1935)

- Maria Rosseels(1916–2005)

- Maurits Sabbe(1873–1938)

- Paul Snoek(1933–1981)

- Stijn Streuvels(1871–1969)

- Herman Teirlinck(1879–1967)

- Jotie T'Hooft(1956–1977)

- Felix Timmermans(1886–1947)

- Ernest Van der Hallen(1898–1948)

- Marcel van Maele(1931–2009)

- Paul van Ostaijen(1896–1928)

- Paul Verhaeghen(born 1965)

- Peter Verhelst(born 1962)

- Gerard Walschap(1898–1989)

- Lode Zielens(1901–1944)

See also

[edit]- Antwerp Book Fair

- Archive and Museum for the Flemish Culture

- Belgian literature

- Chamber of rhetoric

- Dutch literature

- List of Dutch writers

- Medieval Dutch literature

- Nineteenth-century Dutch literature

Notes

[edit]- ^abcdefgGosse 1911,p. 495.

- ^Gosse 1911,pp. 495–496.

- ^Gosse 1911,p. 496.

References (from 19th century)

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Gosse, Edmund William(1911). "Flemish Literature".InChisholm, Hugh(ed.).Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 495–496.This article in turn cites:

- Ida van Düringsfeld,Von der Schelde bis zur Mass. Des geistige Leben der Vlamingen(Leipzig, 3 vols., 1861)

- J. Stecher,Histoire de la littérature néerlandaise en Belgique(1886)

- Theodoor Coopman and L. Scharpé,Geschiedenis der Vlaamsche Letterkunde van het jaar 1830 tot heden(1899)

- A. de Koninck,Bibliographie nationale(3 vols., 1886–1897)

- Paul Hamelius,Histoire poétique et littéraire du mouvement flamand(1894)

- Frans de Potter,Vlaamsche Bibliographie,issued by the Flemish Academy of Ghent — contains a list of publications between 1830 and 1890

- W. J. A. Hubertset al.,Biographisch woordenboeck der Noord- en Zuid-Nederlandsche Letterkunde(1878)