Four Barbarians

| Four Barbarians | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | BốnDi | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | four barbarians | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese Alpha bet | tứ di | ||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | BốnDi | ||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 사이 | ||||||||

| Hanja | BốnDi | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | BốnDi | ||||||||

| Hiragana | しい | ||||||||

| |||||||||

"Four Barbarians"(Chinese:Bốn di;pinyin:sìyí) was a term used by subjects of theZhouandHan dynastiesto refer to the four major people groups living outside the borders ofHuaxia.Each was named for a cardinal direction: theDongyi( "Eastern Barbarians" ),Nanman( "Southern Barbarians" ),Xirong( "Western Barbarians" ), andBeidi( "Northern Barbarians" ). Ultimately, the four barbarian groups either emigrated away from the Chinese heartland or were partly assimilated throughsinicizationintoChinese cultureduring laterdynasties.After this early period, "barbarians" to the north and the west would often be designated as"Hu"( hồ ).

Etymology[edit]

Ancient Chinawas composed of a group of states that arose in theYellow Rivervalley. According to historian Li Feng, during theZhou dynasty(c. 1041–771 BCE), the contrast between the 'Chinese' Zhou and the 'non-Chinese'XirongorDongyiwas "more political than cultural or ethnic".[1]Lothar von Falkenhausen argues that the perceived contrast between "Chinese" and "Barbarians" was accentuated during theEastern Zhouperiod (770–256 BCE), when adherence to Zhou rituals became increasingly recognised as a "barometer of civilisation"; a meter for sophistication and cultural refinement.[2]The Chinese began making adistinction between China (Hua) and the barbarians (Yi)during that period.[3]Huaxia,the earliest concept of "China", was at the center oftianxia( "[everywhere] under heaven; the world" ). It was surrounded by "Four Directions/Corners" (BốnPhương;sìfāng), "Four Lands/Regions" (BốnThổ;sìtǔ), "Four Seas",and" Four Barbarians/Foreigners ". The textEryafrom the late Zhou dynasty defines the Four Seas as "the place where the barbarians lived, hence by extension, the Four Barbarians... are called the four seas".[4]: Chapter 9

The Four Barbarians were theYito the east of China,Manin the south,Rongin the west, andDiin the north.[a]Scholars such asHerrlee Glessner Creel[6]argue thatYi,Man,Rong,andDiwere originally Chinese names of particular ethnic groups or tribes. During theSpring and Autumn period(771–476 BC), these four exonyms were expanded into "general designations referring to the barbarian tribes" in a given cardinal direction.[7]For example, "Yi"became"Dongyi",literally meaning" East(ern)Yi".[b]The Russian anthropologistMikhail Kryukovconcludes:

This would, in the final analysis, mean that once again territory had become the primary criterion of the we-group, whereas the consciousness of common origin remained secondary. What continued to be important were the factors of language, the acceptance of certain forms of material culture, the adherence to certain rituals, and, above all, the economy and the way of life. Agriculture was the only appropriate way of life for the [Huaxia].[8]

In Chinese, the term "Four Barbarians" uses the character forYi(Di). The sinologistEdwin G. Pulleyblankstates that the nameYi"furnished the primary Chinese term for 'barbarian'," despite paradoxically being "considered the most civilized of the non-Chinese peoples."[9][c]Schuessler[10]definesYias "The name of non-Chinese tribes, prob[ably] Austroasiatic, to the east and southeast of the central plain (Shandong, Huái River basin), since the Spring and Autumn period also a general word for 'barbarian'", and proposes a "sea" etymology, "Since the ancient Yuè (=Viet) word for 'sea' is said to have beenyí,the people's name might have originated as referring to people living by the sea ".Yiis the Modern Chinese pronunciation. TheOld Chinesepronunciation is reconstructed as*dyər(Bernhard Karlgren), *ɤier(Zhou Fagao), *ləj(William H. Baxter), and *l(ə)i(Axel Schuessler). Schuessler[10]definesYias "The name of non-Chinese tribes, prob[ably] Austroasiatic, to the east and southeast of the central plain (Shandong, Huái River basin), since the Spring and Autumn period also a general word for 'barbarian'", and proposes a "sea" etymology, "Since the ancient Yuè (=Viet) word for 'sea' is said to have beenyí,the people's name might have originated as referring to people living by the sea ".

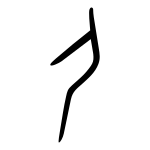

The modern character foryi(Di), like theQin dynastyseal script,is composed ofĐại"big" andCung"bow" – but the earliestShang dynastyoracle bone scriptwas used interchangeably foryiandshiThi"corpse", depicting a person with bent back and dangling legs.[11]The archeologist and scholarGuo Moruobelieved the oracle graph foryidenotes "a dead body, i.e., the killed enemy", while the bronze graph denotes "a man bound by a rope, i.e., a prisoner or slave".[12]Ignoring this historicalpaleography,the Chinese historianK. C. Wuclaimed thatYishould not be translated as "barbarian" because the modern graph implies a big person carrying a bow, someone to perhaps be feared or respected, but not to be despised.[13]The scholarLéon Wiegerprovided multiple definitions to the termyi:“The men đại armed with bows cung, the primitive inhabitants, barbarians, borderers of the Eastern Sea, inhabitants of the South-West countries."[14]Hanyu Da Cidian,[15]a major Chinese language dictionary, notesSiyias derogatory: "Cổ đại Hoa Hạ tộc đối tứ phương số nhỏ dân tộc gọi chung. Đựng khinh miệt chi ý." [Contrasting with the ancient Chinese people, a name forethnic minoritiesin all four directions. Contains a pejorative meaning.]

"Four barbarians" is the common English translation ofSiyi.Compare these Chinese-English dictionary equivalents forSiyi:"the four barbarian tribes on the borders of ancient China",[16]"the barbarians on borders of China",[17]and "four barbarian tribes on the borders".[18]Some scholars interpret thesi"four" inSiyiassifang( tứ phương "four directions" ). Liu Xiaoyuan says the meaning ofSiyi"is not 'four barbarians' but numerous 'barbarous tribes' in the four directions".[19]However, Liu also states that the termyimight have been used by the early Chinese to simply mean "ordinary others". Yuri Pines translatesSiyias "barbarians of the four corners".[20]

InChinese Buddhism,siyi( bốn di ) orsiyijie( bốn di giới ) abbreviates thesi boluoyi( bốn sóng la di ) "FourParajikas"(grave offenses that entail expulsion of a monk or nun from thesangha).

Western Zhou usages[edit]

Bronze inscriptionsand reliable documents from theWestern Zhouperiod (c. 1046–771 BCE) used the wordYiin two meanings, says Chinese sinologist Chen.[21]First,YiorYifang( di phương ) designated a specific ethnic group that had battled against the Shang since the time of KingWu Ding.Second,Yimeant specifically or collectively (e.g.,zhuyiChư di ) peoples in the remote lands east and south of China, such as the well-known Dongyi ( đông di ), Nanyi ( nam di ), and Huaiyi ( hoài di ). Western Zhou bronzes also record the names of some little-knownYigroups, such as the Qiyi ( kỷ di ), Zhouyi ( thuyền di ), Ximenyi ( Tây Môn di ), Qinyi ( Tần di ), and Jingyi ( kinh di ). Chen notes, "Theseyiare not necessarily identical with the numerousyiin Eastern Zhou literature. On the contrary, except for theHuaiyi,DongyiandNanyi,theseyiall seem to have vanished from the historical and inscriptional accounts of the Eastern Zhou ".[22]

Inscriptions on bronzeguivessels (including the Xun tuân, Shiyou sư dậu, and Shi Mi sử mật ) do not always use the termyiexclusively in reference to alien people of physically different ethnic groups outside China. According to Chen, "yi"was also used for" certain groups of people residing in places within the region of Zhou control ".[23]

Expanding upon the research ofLi Lingthat Western Zhou bronze writings differentiate the Zhou people (WangrenVương người, lit. "king's people" ) from other peoples (yiDi ), Chen found three major categories:[24]people of Zhou, people of Shang, and people ofYi(neither Zhou nor Shang). "The Zhou rulers treated the Shang remnant elites with courtesy and tolerance, whereas they treatedyipeople with less respect. "Shang people were employed in positions based upon their cultural legacy and education, such aszhuChúc "priest",zongTông "ritual official",buBặc "diviner",shiSử "scribe", and military commander.Yipeople, who had a much lower status, served the rulers in positions such as infantry soldiers, palace guards, servants, and slave laborers. Chen compares the social status ofYiwith "xiangrenHàng người, people captured from other states or ethnicities, or their descendants ".[21]

Chen analyzed diachronic semantic changes in the twin concepts ofXiaandYi.[25]During the Western Zhou, they were employed to distinguish "between the Zhou elite and non-Zhou people"; during the Eastern Zhou, they distinguished "between the central states and peripheral barbarian tribes in a geographical sense, as well as between Zhou subjects and non-Zhou subjects in a political sense." Eastern Zhou canonical texts, says Chen, "frequently assert a differentiation betweenXia(orZhongguo), meaning those states in the central plains subject to the Zhou sovereign, andYiDi,DiĐịch,RongNhung, andManMan, all of which could be used generally to refer to non-Chinese ethnic groups ".[26]Among these four terms,Yiwas most widely employed for "barbarian" clans, tribes, or ethnic groups. The Chinese classics used it in directional compounds (e.g., "eastern"DongyiĐông di, "western"XiyiTây Di, "southern"Nanyi,and "northern"BeiyiBắc di ), numerical (meaning "many" ) generalizations ( "three"SanyiTam di, "four"SiyiBốn di, and "nine"JiuyiChín di ), and groups in specific areas and states (HuaiyiHoài di,ChuyiSở di,QinyiTần di, andWuyiNgô di ).

Historians Liu Junping and Huang Deyuan[27]describe how early Chinese monarchs used the concept of the Four Barbarians to justify their rule. Just howheaven (yang) was matched with the inferior earth (yin),"the Chinese as an entity was matched with the inferior ethnic groups surrounding it in its four directions so that the kings could be valued and the barbarians could be rejected." Lius and Huang propose that later Chinese ideas about the "nation" and "state" of China evolved from the "casual use of such concepts as"Tianxia"...and" Four Barbarians "."[28]

Eastern Zhou usages[edit]

TheChinese classicscontain many references to theSiyi"Four Barbarians". Around the lateSpring and Autumn period(771–476 BCE) or earlyWarring States period(475–221 BCE), the namesMan,Yi,Rong,andDibecame firmly associated with the cardinal directions.Yichanged from meaning a specific "barbarians in the east" to "barbarians" generally, and two new words –SiyiandMan-Yi-Rong-DiMan di nhung địch – referred to "all non-Zhou barbarians in the four directions". TheZuozhuanandMozicontain the earliest extant occurrences ofSiyi.

The (early 4th century BCE)Zuozhuancommentary to theChunqiu( "Spring and Autumn Annals") usesSiyifour times.

The affair [presenting Rong prisoners and spoils of war to Duke Zhuang] was contrary to rule. When a prince has gained success over any of the wild tribes, he presents the spoils to the king, who employs them to terrify other tribes.[29]

It is virtue by which the people of the Middle State are cherished; it is by severity that the wild tribes around are awed.[30]

I have heard that, when the officers of the son of Heaven are not properly arranged, we may learn from the wild tribes all about.[31]

Anciently, the defenses of the sons of Heaven were the rude tribes on every side of the kingdom; and when their authority became low, their defenses were the various States.[32]

In addition, theZuozhuanhas an early usage ofMan-Yi-Rong-DiMan di nhung địch meaning "all kinds of barbarians".

When any of the wild tribes, south, east, west, or north, do not obey the king's commands, and by their dissoluteness and drunkenness are violating all the duties of society, the king gives command to attack them.[33]

The (c. 4th century BCE)Mozihas one occurrence ofSiyireferring toKing Wu of Zhou.

After King Wu had conquered the Shang dynasty and received the gifts bestowed by God, he assigned guardians to the various spirits, instituted sacrifices to Zhou's ancestors, the former kings of Shang, and opened up communications with the barbarians of the four quarters, so that there was no one in the world who did not pay him allegiance.[34]

The (c. 4th century BCE)Guanzirecounts howDuke Huan of Qi(d. 643 BCE) conquered all his enemies, including theDongyiĐông di,XirongTây Nhung,NanmanNam Man, andBeidiBắc Địch.

Further to the west, he subjugated the Western Yu, of Liusha and for the first time the Rong people of Qin were obedient. Therefore, even, though the soldiers went forth only once, their great accomplishments [victories] numbered twelve, and as a consequence none of the eastern Yi, western Rong, southern Man, northern Di, or the feudal lords of the central states failed to submit.[35]

This text[36]also recommends, "To use the states bordering the four seas to attack other states bordering the four seas is a condition distinguishing the central states."

The (c. 4th century BCE) ConfucianAnalectsdoes not useSiyi,but does useJiuyiChín di "Nine Barbarians" (9/19),[37]"The Master wanted to settle among the Nine Wild Tribes of the East. Someone said, I am afraid you would find it hard to put up with their lack of refinement. The Master said, Were a true gentleman to settle among them there would soon be no trouble about lack of refinement."YidiDi địch "Eastern and Northern Barbarians" occurs twice,[38]"The Master said, The barbarians of the East and North have retained their princes. They are not in such a state of decay as we in China"; "The Master said, In private life, courteous, in public life, diligent, in relationships, loyal. This is a maxim that no matter where you may be, even amid the barbarians of the east or north, may never be set aside." This text has an indirect reference to "barbarians" (5/6),[39]"The Master said, The Way makes no progress. I shall get upon a raft and float out to sea."

The (c. 290 BCE) ConfucianistMencius(1A/7)[40]usesSiyionce when Mencius counselsKing Xuan of Qi(r. 319–301 BCE) against territorial expansion: "You wish to extend your territory, to enjoy the homage of Ch'in and Ch'u, to rule over the Central Kingdoms and to bring peace to the barbarian tribes on the four borders. Seeking the fulfillment of such an ambition by such means as you employ is like looking for fish by climbing a tree." This text (3A/4)[41]usesYiDi in quoting Confucius, "I have heard of the Chinese converting barbarians to their ways, but not of their being converted to barbarian ways."

TheMenciususes westernXiyiTây Di four times (three contrasting with northernBeidiBắc Địch ), easternDongyiĐông di once, andYidiDi địch once. Three repeatedXiyioccurrences (1B/11)[42]describeTang of Shangestablishing the Shang dynasty: "With this he gained the trust of the Empire, and when he marched on the east, the western barbarians complained, and when he marched on the south, the northern barbarians complained. They all said, 'Why does he not come to us first?'"Dongyioccurs in a claim (4B/1)[43]that the legendary Chinese sagesShunandKing Wen of ZhouwereYi:"Mencius said, 'Shun was an Eastern barbarian; he was born in Chu Feng, moved to Fu Hsia, and died in Ming T'iao. Ken Wen was a Western barbarian; he was born in Ch'i Chou and died in Pi Ying."Yidioccurs in context (3B/9)[44]with theDuke of Zhou,"In ancient times, Yu controlled the Flood and brought peace to the Empire; the Duke of Chou subjugated the northern and southern barbarians, drove away the wild animals, and brought security to the people."

The (c. 3rd century BCE)XunziusesSiyitwice in one chapter.

If your deportment is respectful and reverent, your heart loyal and faithful, if you use only those methods sanctioned by ritual principles and moral duty, and if your emotional disposition is one of love and humanity, then though you travel throughout the empire, and though you find yourself reduced to living among the Four Yi di tribes, everyone would consider you to be an honorable person. If you strive to be the first to undertake toilsome and bitter tasks and can leave pleasant and rewarding tasks to others, if you are proper, diligent, sincere, and trustworthy, if you take responsibility and oversee it meticulously, then wherever you travel in the civilized world and though you find yourself reduced to living with the Four Tribes, everyone would be willing to entrust you with official duties.[45]

John Knoblock notes,[46]"The 'Four Yi tribes' refers to the barbarians surrounding the Chinese" Middle Kingdom "and does not designate particular peoples". TheXunziusesMan-Yi-Rong-Dionce.

Accordingly, [ chư hạ ] all the states of Xia Chinese have identical obligations for service to the king and have identical standards of conduct. The countries of Man, Yi, Rong, and Di barbarians perform the same obligatory services to the kind, but the regulations governing them are not the same.… The Man and Yi nations do service according to treaty obligations. The Rong and Di do irregular service.[47]

The (3rd–1st centuries BCE)LijiusesSiyionce.

But if it be his character, when he finds men of ability, to be jealous and hate them; and, when he finds accomplished and perspicacious men, to oppose them and not allow their advancement, showing himself really not able to bear them: such a minister will not be able to protect my sons and grandsons and people; and may he not also be pronounced dangerous to the state? "It is only the truly virtuous man who can send away such a man and banish him, driving him out among the barbarous tribes around, determined not to dwell along with him in the Middle Kingdom.[48]

TheLijialso gives detailed information about the Four Barbarian peoples.

The people of those [wufangNgũ phương ] five regions – the Middle states, and the Rong, Yi, (and other wild tribes round them) – had all their several natures, which they could not be made to alter. The tribes on the east were called Yi. They had their hair unbound, and tattooed their bodies. Some of them ate their food without its being cooked. Those on the south were called Man. They tattooed their foreheads, and had their feet turned in towards each other. Some of them (also) ate their food without its being cooked. Those on the west were called Rong. They had their hair unbound, and wore skins. Some of them did not eat grain-food. Those on the north were called Di. They wore skins of animals and birds, and dwelt in caves. Some of them also did not eat grain-food. The people of the Middle states, and of those Yi, Man, Rong, and Di, all had their dwellings, where they lived at ease; their flavours which they preferred; the clothes suitable for them; their proper implements for use; and their vessels which they prepared in abundance. In those five regions, the languages of the people were not mutually intelligible, and their likings and desires were different. To make what was in their minds apprehended, and to communicate their likings and desires, (there were officers) – in the east, called transmitters; in the south, representationists; in the west, Di-dis; and in the north, interpreters.[49]

TheShujinghistory usesSiyiin two forged "Old Text" chapters.

Yi said, 'Alas! be cautious! Admonish yourself to caution, when there seems to be no occasion for anxiety. Do not fail to observe the laws and ordinances.… Do not go against what is right, to get the praise of the people. Do not oppose the people's (wishes), to follow your own desires. (Attend to these things) without idleness or omission, and the barbarous tribes all around will come and acknowledge your sovereignty.'[50]

The king said, 'Oh! Grand-Master, the security or the danger of the kingdom depends on those officers of Yin. If you are not (too) stern with them nor (too) mild, their virtue will be truly cultivated.… The penetrating power of your principles, and the good character of your measures of government, will exert an enriching influence on the character of the people, so that the wild tribes, with their coats buttoning on the left, will all find their proper support in them, and I, the little child, will long enjoy much happiness.[51]

The (c. 239 BCE)Lüshi Chunqiuhas two occurrences ofSiyi.

Seeking depth, not breadth, reverently guarding one affair… When this ability is utterly perfect, the barbarian Yi states of the four quarters are tranquil. (17/5)[52]

If your desires are not proper and you use them to govern your state, it will perish. Therefore, the sage-kings of antiquity paid particular attention to conforming to the endowment Heaven gave them in acting on their desires; all the people, therefore, could be commanded and all their accomplishments were firmly established. "The sage-kings held fast to the One, and the barbarians of the four directions came to them" refers to this. (19/6)[53]

The DaoistZhuangziusesSiyitwice in the (c. 3rd century BCE) "Miscellaneous Chapters".

The sword of the son of heaven has a point made of Swallow Gorge and Stone Wall… It is embraced by the four uncivilized tribes, encircled by the four seasons, and wrapped around by the Sea of Po. (30)[54]

Master Mo declared, "Long ago, when Yü was trying to stem the flood waters, he cut channels from the Yangtze and the Yellow rivers and opened communications with the four uncivilized tribes and the nine regions. (33)[55]

Han usages[edit]

Many texts dating from theHan dynasty(206 BCE-220 CE) used the ethnonymsYiandSiyi.

For example, the (139 BCE)Huainanzi,which is an eclectic compilation attributed toLiu An,usesSiyi"Four Barbarians" in three chapters (andJiuyi"Nine Barbarians" in two).

Yuunderstood that the world had become rebellious and thereupon knocked down the wall [built by his fatherGunto protect Xia], filled in the moat surrounding the city, gave away their resources, burned their armor and weapons, and treated everyone with beneficence. And so the lands beyond the Four Seas respectfully submitted, and the four Yi tribes brought tribute. (1.6)[56]

The Three Miao [tribes] bind their heads with hemp; the Qiang people bind their necks: the [people of] the Middle Kingdom use hat and hatpin; the Yue people shear their hair. In regard to getting dressed, they are as one.… Thus the rites of the four Yi [ "barbarians" ] are not the same, [yet] they all revere their ruler, love their kin, and respect their elder brothers. (11.7)[57]

When Shun was the Son of Heaven, he plucked the five-stringedqinand chanted the poems of the "Southern Airs" [aShijingsection], and thereby governed the world. Before the Duke of Zhou had gathered provisions or taken the bells and drums from their suspension cords, the four Yi tribes submitted. (20.16)[58]

Thus when the Son of Heaven attains the Way, he is secure [even] among the four Yi [tribes of "barbarians" ]; when the son of Heaven loses the way, he is secure [only] among the Lords of the Land. (20.29)[59]

References to the "Four Barbarians" are especially common among Han-era histories;Siyioccurs 18 times in theShiji,62 in theHan Shu,and 30 in theHou Han Shu.

To evaluate the traditional "civilized vs. barbarian" dichotomy that many scholars use as a blanket description of Chinese attitudes towards outsiders, Erica Brindley examined how the Chinese classics ethnically described the southernYue peoples.[60]Brindley found that many early authors presented the Yue in various ways and not in a simplistic manner. For instance,Sima Qian's (c. 109–91 BCE)Shijihistory traces the Chinese lineage ofKing Gou gian of Yueback toYu the Great,legendary founder of the Xia dynasty (41):[61]"Gou Jian, the king of Yue, was the descendant of Yu and the grandson of Shao Kang of the Xia. He was enfeoffed at Kuaiji and maintained ancestral sacrifices to Yu. [The Yue] tattooed their bodies, cut their hair short, and cleared out weeds and brambles to set up small fiefs." On the one hand, this statement conceptualizes the Yue people through alien habits and customs, but on the other, through kinship-based ethnicity. Sima Qian also states (114):[62]"Although the Yue are considered to be southern (manMan ) barbarians (yiDi ), is it not true that their ancestors had once benefited the [Yue] people with their great merit and virtue? "Sima denigrates the Yue by calling them “Man Yi,” but he also "counterbalances such language and descriptions by proving the honor of Yue ancestry and certain of its individual members."[63]

Brindley further notes that,

I translate "Man Yi" above as "Southern barbarian," and not just as the Man and Yi peoples, because it is clear that Sima Qian does not think of them as two distinct groups. Rather, it appears that the term Yi does not point to any particular group… but to a vague category of degraded other. Man, on the other hand, denotes not the specific name of the group ( "Yue" ) but the general southern location of this specific derogatory other. In the literary tradition, the four directions (north, south, east, west) are linked with four general categories of identification denoting a derogatory other (di,man,yi,rong).[64]

In the end, Brindley concludes that,

Much scholarship dealing with the relationship between self and other in Chinese history assumes a simple bifurcation between civilized Chinese or Han peoples and the barbarian other. In this analysis of the concepts of the Yue and Yue ethnicity, I show that such a simple and value-laden categorization did not always exist, and that some early authors differentiated between themselves and others in a much more complicated and, sometimes, conflicted manner.[65]

The complexities of the meaning and usage ofYiis also shown in theHou Han Shu,where in its chapter on theDongyi,the books describes theDongyicountries as places where benevolence rules and the gentlemen do not die.

TheShuowen Jiezi(121 CE) character dictionary, definesyias "men of the east” ( phương đông người cũng ).[citation needed]

Later usages[edit]

ChineseYi"barbarian" andSiyicontinued to be used long after the Han dynasty, as illustrated by the following examples from theMing dynasty(1368–1644) andQing dynasty(1644–1912).

The Dutch sinologistKristofer Schippercites a (c. 5th–6th century)Celestial MastersDaoist document (Xiaren Siyi shou yaoluHạ nhân bốn di chịu muốn lục ) that substitutesQiangKhươngfor ManManin theSìyí.[66]

Sìyí guǎnChinese:Tứ Di Quán(lit. "Four Barbarians building" ) was the name of theMingimperial "Bureau of Translators"for foreigntributary missionsto China. Norman Wild says that in the Zhou dynasty, interpreters were appointed to deal with envoys bringing tribute or declarations of loyalty.[67]TheLijirecords regional "interpreter" words for theSìyí:jiGửifor theDongyi,xiangTượngfor theNanman,didiĐịchĐêfor theXirong,andyiDịchfor theBeidi.In theSui,Tang,andSongdynasties, tributary affairs were handled by theSìfāng guǎnlit.'Four corners/directions building'. The MingYongle Emperorestablished theSìyí guǎnTứ Di Quán"Bureau of Translators" for foreign diplomatic documents in 1407, as part of the imperialHanlin Academy.Ming histories also mentionHuárén YíguānNgười Hoa di quan "Chinese barbarian officials"[68]denoting people of Chinese origin employed by rulers of the "barbarian vassal states" in their tributary embassies to China. When theQing dynastyrevived the MingSìyíguǎnTứ Di Quán,theManchus,who "were sensitive to references to barbarians",[69]changed the name from pejorativeyíDi "barbarian" toyíDi"Yi people(a Chinese ethnic minority) ".

In 1656, the Qing imperial court issued an edict to Mongolia about aterritorial dispute,[70]"Those barbarians (fanyi) who paid tribute to Mongolia during the Ming should be administered by Mongolia. However, those barbarians submitting to the former Ming court should be subjects of China "

After China began expansion intoInner Asia,Gang Zhao says,[71]"Its inhabitants were no longer to be considered barbarians, a term suitable for the tributary countries, and an error on this score could be dangerous." In a 1787 memorial sent to theQianlong Emperor,theShaanxigovernor mistakenly called a Tibetan mission anyísh3Di sử "barbarian mission". The emperor replied, "Because Tibet has long been incorporated into our territory, it is completely different from Russia, which submits to our country only in name. Thus, we cannot see the Tibetans as foreign barbarians, unlike the Russians".

The use ofYíDi continued into modern times. TheOxford English Dictionarydefinesbarbarian(3.c) as, "Applied by the Chinese contemptuously to foreigners", and cites the 1858Treaty of Tientsinprohibiting the Chinese from calling the British "Yí". (Article LI) states, "It is agreed, that henceforward the character" I "Di ('barbarian') shall not be applied to the Government or subjects of Her Britannic Majesty, in any Chinese official document." This prohibition in the Treaty of Tientsin had been the end result of a long dispute between the Qing and British officials regarding the translation, usage and meaning ofYí.Many Qing officials argued that the term did not mean “barbarians,” but their British counterparts disagreed with this opinion. Using the linguistic concept ofheteroglossia,Lydia Liuanalyzed the significance ofyíin Articles 50 and 51 as a "super-sign":

The law simply secures a three-way commensurability of the hetero-linguistic signDi /i/barbarianby joining the written Chinese character, the romanized pronunciation, and the English translation together into a coherent semantic unit. [Which] means that the Chinese characteryibecomes a hetero-linguistic sign by virtue of being informed, signified, and transformed by the English word "barbarian" and must defer its correct meaning to the foreign counterpart.... That is to say, whoever violates the integrity of the super-signDi /i/barbarian... risks violating international law itself.[72]

See also[edit]

- Four Perils,which included "barbarian" tribes in ancient Chinese history

- Five Barbarians,later groups that settled innorthern China

Notes[edit]

- ^William H. BaxterandLaurent Sagartreconstruct theOld Chinesenames of the four barbarian tribes as:[5]

- ^The namesYi,Man,Rong,andDiwere further generalized intocompounds(such asRongdi,Manyi,andManyirongdi) denoting "non-Chinese; foreigners; barbarians."Traditional Chinese charactersfor these terms all include aradicalmeaning "animal/insect".simplified charactersuse the radical meaning "dog" instead.[citation needed]

- ^Yiwas used both for the names of specific barabarian groups (e.g., theHuaiyi,meaning "Huai Riverbarbarians ") and generalized references to" barbarian "

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Li 2006,p. 286. Li explains that "Rong" meant something like "warlike foreigners" and "Yi" was close to "foreign conquerables".

- ^von Falkenhausen 1999,p. 544.

- ^Shelach 1999,pp. 222–23.

- ^Wilkinson, Endymion (2000),Chinese History: a manual,revised and enlarged ed., Harvard University Asia Center. p. 710.

- ^Baxter, William H. and Laurent Sagart. 2014.Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction.Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-994537-5.

- ^Creel, Herrlee G.(1970),The Origins of Statecraft in China,The University of Chicago Press. p. 197.

- ^Pu Muzhou (2005),Enemies of Civilization: Attitudes toward Foreigners in Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China,SUNY Press. p.45.

- ^Jettmar, Karl (1983), "The Origins of Chinese Civilization: Soviet Views," In Keightley, David N., ed.The Origins of Chinese civilization,University of California Press. p. 229.

- ^Pulleyblank, E. G., (1983), "The Chinese and Their Neighbors in Prehistoric and Early Historic Times", in Keightley, David N., ed.The Origins of Chinese civilization,University of California Press. p. 440.

- ^abSchuessler, Axel (2007),ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese,University of Hawaii Press. p. 563.

- ^Hanyu Da Zidianweiyuanhui Hán ngữ đại từ điển ủy ban, eds. 1986–1989.Hanyu dazidianHán ngữ đại từ điển ( "Comprehensive Chinese Character Dictionary" ). 8 vols. 1986 ed. vol. 1, p. 527.

- ^Huang Yang (2013), "Perceptions of the Barbarian in Early Greece and China",CHS Research Bulletin 2.1,translating Guo Moruo, (1933, 1982), lời bói thông toản, thứ năm sáu chín phiến. p. 462.

- ^Wu, K.C.(1982),The Chinese Heritage,Crown Publishers. pp. 107–8.

- ^Wieger, Léon (1927),Chinese Characters: Their Origin, Etymology, History, Classification and Signification. A Thorough Study from Chinese Documents,tr. by L. Davrout, 2nd edition, Dover reprint. p. 156.

- ^1993 ed., vol. 3, p. 577

- ^Liang Shih-chiuLương thật thu and Chang Fang-chieh trương phương kiệt, eds. (1971),Far East Chinese-English Dictionary,Far East Book Co.

- ^Lin Yutang(1972),Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage,Chinese University Press.

- ^DeFrancis, John,ed. (2003),ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary,University of Hawaii Press.

- ^Liu Xiaoyuan (2004),Frontier Passages: Ethnopolitics and the Rise of Chinese Communism, 1921–1945(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004). 176, 10–11.

- ^Pines, Yuri (2005). "Beasts or humans: Pre-Imperial origins of Sino-Barbarian Dichotomy", inMongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian nomads and the sedentary world,eds. R. Amitai and M. Biran, Brill:59–102. p. 62.

- ^abZhi 2004,p. 202.

- ^Zhi 2004,p. 200.

- ^Zhi 2004,p. 201.

- ^Zhi 2004,p. 204.

- ^Zhi 2004,p. 186.

- ^Zhi 2004,p. 197.

- ^Liu & Huang 2006,p. 532.

- ^Liu & Huang 2006,p. 535.

- ^Zhuang 31,Legge 1872,p. 119.

- ^Duke Xi 25,Legge 1872,p. 196.

- ^Duke Zhao 17,Legge 1872,p. 668.

- ^Duke Zhao 23,Legge 1872,p. 700.

- ^Cheng 3,Legge 1872,p. 349.

- ^Against Offensive Warfare,tr. Watson, Burton (2003),Mozi: Basic Writings,Columbia University Press. p. 61.

- ^Xioao Kuang,Rickett 1998,p. 341.

- ^Ba Yan,Rickett 1998,p. 365.

- ^Tr.Waley 1938,p. 141

- ^Tr.Waley 1938,(3/5) pp. 94–5; (13/19) p. 176.

- ^Tr.Waley 1938,p. 108.

- ^Tr.Lau 1970,p. 57.

- ^Tr.Lau 1970,p. 103.

- ^Tr.Lau 1970,p. 69; cf. 3B/5 and 7B/4.

- ^Tr.Lau 1970,p. 128.

- ^Tr.Lau 1970,p. 115.

- ^On Self Cultivation,Knoblock 1988,pp. 154–5.

- ^Knoblock 1988,p. 278.

- ^Rectifying Theses, tr. Knoblock 1994: 38–9.[full citation needed]

- ^Great Learning,Legge 1885,p. 367.

- ^Wang Zhi,Legge 1885,pp. 229–30, changed to Pinyin.

- ^3,Legge 1865,p. 47.

- ^52,Legge 1865,p. 249.

- ^Knoblock & Riegel 2000,p. 424.

- ^Knoblock & Riegel 2000,p. 498.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 315.

- ^Mair 1994,p. 327.

- ^Tr.Major et al. 2010,p. 54.

- ^Tr.Major et al. 2010,p. 407.

- ^Tr.Major et al. 2010,p. 813.

- ^Tr.Major et al. 2010,p. 828.

- ^Brindley 2003.

- ^Tr.Brindley 2003,p. 27.

- ^Tr.Brindley 2003,p. 28.

- ^Brindley 2003,p. 31.

- ^Brindley 2003,p. 29.

- ^Brindley 2003,pp. 31–2.

- ^Schipper, Kristofer (1994), "Purity and Strangers Shifting Boundaries in Medieval Taoism",T'oung Pao80.3: 61–81. p. 74.

- ^Wild 1945,p. 617.

- ^Chan 1968,p. 411.

- ^Wild 1945,p. 620.

- ^Tr.Zhao 2006,p. 7.

- ^Zhao 2006,p. 13.

- ^Liu 2004,p. 33.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brindley, Erica Fox (2003), "Barbarians or Not? Ethnicity and Changing Conceptions of the Ancient Yue (Viet) Peoples, ca. 400–50 BC",Asia Major(PDF),3rd Series, vol. 16, Academia Sinica, pp. 1–32,JSTOR41649870.

- Chan, Hok-Lam (1968). "The" Chinese Barbarian Officials "in the Foreign Tributary Missions to China during the Ming Dynasty".Journal of the American Oriental Society.88(3): 411–418.doi:10.2307/596866.JSTOR596866.

- Zhi, Chen (2004)."From Exclusive Xia to Inclusive Zhu-Xia: The Conceptualisation of Chinese Identity in Early China".Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society.14(3).Cambridge University Press:185–205.doi:10.1017/S135618630400389X.JSTOR25188470.S2CID162643600.

- Xunzi, A Translation and Study of the Complete Works, Volume 1, Books 1–6.Translated by Knoblock, John. Stanford University Press. 1988.

- The Annals of Lü Buwei: A Complete Translation and Study.Translated by Knoblock, John; Riegel, Jeffrey. Stanford University Press. 2000.

- Lau, D.C. (1970).Mencius.(2003). Penguin Books.

- The Chinese Classics (vol. III, The Shoo King).Translated byLegge, James.London: Trübner & co. 1865.

- The Chinese Classics (vol. V).Translated byLegge, James.London: Trübner & co. 1872.

- The Li Ki (2 vols).Translated byLegge, James.Oxford:Clarendon Press. 1885.

- Liu, Lydia (2004).The Clash of Empires.Harvard University Press.

- Liu, Junping; Huang, Deyuan (2006)."The Evolution of Tianxia Cosmology and Its Philosophical Implications".Frontiers of Philosophy in China.1(4). Brill: 517–538.doi:10.1007/s11466-006-0023-6.JSTOR30209874.S2CID195310037.

- Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu.Translated by Mair, Victor H. Bantam Books. 1994.

- Major, John S.; Queen, Sarah; Meyer, Andrew; Roth, Harold (2010).The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China, by Liu An, King of Huainan.Columbia University Press.

- Guanzi.Translated by Rickett, W. Allyn. Princeton University Press. 1998.

- Waley, Arthur (1938).The Analects of Confucius.Vintage.

- Wild, Norman (1945). "Materials for the Study of theSsŭ i KuanBốn di dịch quán (Bureau of Translators) ".Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.11(3): 617–640.doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072311.S2CID154048910.

- Zhao, Gang (2006). "Reinventing China: Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity".Modern China.32(1): 3–30.doi:10.1177/0097700405282349.S2CID144587815.

- Li, Feng (17 August 2006).Landscape and Power in Early China: The Crisis and Fall of the Western Zhou 1045–771 BC.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1-139-45688-3.

- Shelach, Gideon (30 April 1999).Leadership Strategies, Economic Activity, and Interregional Interaction: Social Complexity in Northeast China.Springer US.ISBN978-0-306-46090-6.

- von Falkenhausen, Lothar (13 March 1999). "The Waning of the Bronze Age: Material Culture and Social Developments, 770–481 B.C.". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.).The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC.Cambridge University Press. pp. 450–544.ISBN978-0-521-47030-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Shin, Leo (2006),The Making of the Chinese State: Ethnicity and Expansion on the Ming Borderlands,Cambridge University Press.