Four occupations

Thefour occupations(simplified Chinese:Sĩ nông công thương;traditional Chinese:Sĩ nông công thương;pinyin:Shì nóng gōng shāng), or "four categories of the people"(Chinese:Tứ dân;pinyin:sì mín),[1][2]was anoccupationclassificationused inancient Chinaby eitherConfucianorLegalistscholars as far back as the lateZhou dynastyand is considered a central part of thefeng giansocial structure(c. 1046–256 BC).[3]These were theshi(warrior nobles, and later ongentryscholars), thenong(peasant farmers), thegong(artisans and craftsmen), and theshang(merchants and traders).[3] The four occupations were not always arranged in this order.[4][5]The four categories were not socioeconomic classes; wealth and standing did not correspond to these categories, nor were they hereditary.[1][6]

The system did not factor in all social groups present in premodern Chinese society, and its broad categories were more an idealization than a practical reality. Thecommercializationof Chinese society in theSongandMingperiods further blurred the lines between these four occupations. The definition of the identity of theshiclass changed over time—from warriors to aristocratic scholars, and finally to scholar-bureaucrats. There was also a gradual fusion of the wealthy merchant and landholding gentry classes, culminating in the late Ming dynasty.

In some manner, this system of social order was adopted throughout theChinese cultural sphere.In Japanese it is called "Shi, nō, kō, shō"(Sĩ nông công thương,shinōkōshō),and the three under thesamuraiclass were equal social and occupational classifications,[7][8][9]while theshiwas modified into a hereditary class, the samurai.[10][11]In Korean it is called "Sa, nong, gong, sang" (사농공상), and in Vietnamese is called "Sĩ, nông, công, thương ( sĩ nông công thương ). The main difference in adaptation was the definition of theshi( sĩ ).

Background

[edit]

From existing literary evidence, commoner categories in China were employed for the first time during theWarring States period(403–221 BC).[12]Despite this,Eastern-Han(AD 25–220) historianBan Gu(AD 32–92) asserted in hisBook of Hanthat the four occupations for commoners had existed in theWestern Zhou(c. 1050–771 BC) era, which he considered agolden age.[12]However, it is now known that the classification of four occupations as Ban Gu understood it did not exist until the 2nd century BC.[12]Ban explained the social hierarchy of each group in descending order:

Scholars, farmers, artisans, and merchants; each of the four peoples had their respective profession. Those who studied in order to occupy positions of rank were called theshi(scholars). Those who cultivated the soil and propagated grains were callednong(farmers). Those who manifested skill (qiao) and made utensils were calledgong(artisans). Those who transported valuable articles and sold commodities were calledshang(merchants).[13]

TheRites of Zhoudescribed the four groups in a different order, with merchants before farmers.[14]The Han-era textGuliang Zhuanplaced merchants second after scholars,[4]and the Warring States-eraXunziplaced farmers before scholars.[5]TheShuo Yuanmentioned a quotation which stressed the ideal of equality between the four occupations.[15]

Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Professor of Early Chinese History at theUniversity of California, Santa Barbara,writes that the classification of "four occupations" can be viewed as a mere rhetorical device that had no effect on government policy.[12]However, he notes that although no statute in the Qin or Han law codes specifically mentions the four occupations, some laws did treat these broadly classified social groups as separate units with different levels of legal privilege.[12]

The categorisation was sorted according to the principle of economic usefulness to state and society, that those who used mind rather than muscle (scholars) were placed first, with farmers, seen as the primary creators of wealth, placed next, followed by artisans, and finally merchants who were seen as a social disturbance for excessive accumulation of wealth or erratic fluctuation of prices.[16]Beneath the four occupations were the "mean people" (Chinese:Tiện dânjiànmín), outcasts from "humiliating" occupations such as entertainers and prostitutes.[17]

The four occupations were not a hereditary system.[1][6]The four occupations system differed from those of European feudalism in that people were not born into the specific classes, such that, for example, a son born to a gong craftsman was able to become a part of the shang merchant class, and so on. Theoretically, any man could become an official through the Imperial examinations.[17]

From the fourth century BC, theshiand some wealthy merchants worelong flowing silken robes,while the working class wore trousers.[18]

Shī ( sĩ )

[edit]Ancient Warrior class

[edit]

During the ancientShang(1600–1046 BC),Western Zhou(1046–771 BC),Spring and Autumn(770-481 BC), and earlyWarring States(475-221 BC) periods, theshiwere a knightly social order of low-level aristocratic lineage compared todukes and marquises.[19]Theshiwere distinguished by their right to ride and command battles from chariots, while they also served civil functions.[19]Initially rising to power through controlling the new technology ofbronzeworking,from 1300 BC, theshitransitioned from foot knights to being primarily chariotarchers,fighting withcompositerecurvedbow, a double-edged sword known as theGian,and armour.[20]

Theshihad a strict code ofchivalry.In the battle of Zheqiu, 420 BC, theshiHua Bao shot at and missed anothershiGongzi Cheng, and just as he was about to shoot again, Gongzi Cheng said that it was unchivalrous to shoot twice without allowing him to return a shot. Hua Bao lowered his bow and was subsequently shot dead.[20][21]In 624 BC a disgracedshifrom theState of Jinled a suicidal charge of chariots to redeem his reputation, turning the tide of the battle.[20]In theBattle of Bi,597 BC, the routing chariot forces of Jin were bogged down in mud, but pursuing enemy troops stopped to help them get dislodged and allowed them to escape.[22]

As chariot warfare became eclipsed by mounted cavalry and infantry units with effective crossbowmen in theWarring States period,the participation of theshiin battle dwindled as rulers sought men with actual military training, not just aristocratic background.[23]This was also a period wherephilosophical schools flourished in China,while intellectual pursuits became highly valued amongst statesmen.[24]Thus, theshieventually became renowned not for their warrior's skills, but for their scholarship, abilities in administration, and sound ethics and morality supported by competing philosophical schools.[25]

Scholar-Officials

[edit]

UnderDuke Xiao of Qinand the chief minister and reformerShang Yang(d. 338 BC), the ancientState of Qinwas transformed by a newmeritocraticyet harsh philosophy of Legalism. This philosophy stressed stern punishments for those who disobeyed the publicly known laws while rewarding those who labored for the state and strove diligently to obey the laws. It was a means to diminish the power of the nobility, and was another force behind the transformation of theshiclass from warrior-aristocrats into merit-driven officials. When theQin dynasty(221–206 BC) unified China under the Legalist system, the emperor assigned administration to dedicated officials rather than nobility, ending feudalism in China, replacing it with a centralized, bureaucratic government. The form of government created by the first emperor and his advisors was used by later dynasties to structure their own government.[26][27][28]Under this system, the government thrived, as talented individuals could be more easily identified in the transformed society. However, the Qin became infamous for its oppressive measures, and socollapsed into a state of civil warafter the death of the Emperor.

The victor of this war wasLiu Bang,who initiated four centuries of unification ofChina properunder theHan dynasty(202 BC–AD 220). In 165 BC,Emperor Wenintroduced the first method of recruitment to civil service through examinations, whileEmperor Wu(r. 141–87 BC), cemented the ideology ofConfuciusinto mainstream governance installed a system of recommendation and nomination in government service known asxiaolian,and a national academy[29][30][31]whereby officials would select candidates to take part in an examination of theConfucian classics,from which Emperor Wu would select officials.[32]

In theSui dynasty(581–618) and the subsequentTang dynasty(618–907) theshiclass would begin to present itself by means of the fully standardizedcivil service examination system,of partial recruitment of those who passedstandard examsand earned an official degree. Yet recruitment by recommendations to office was still prominent in both dynasties. It was not until theSong dynasty(960–1279) that the recruitment of those who passed the exams and earned degrees was given greater emphasis and significantly expanded.[33]Theshiclass also became less aristocratic and more bureaucratic due to the highly competitive nature of the exams during the Song period.[34]

Beyond serving in the administration and the judiciary, scholar-officials also provided government-funded social services, such as prefectural or county schools, free-of-charge public hospitals, retirement homes and paupers' graveyards.[35][36][37]Scholars such asShen Kuo(1031–1095) andSu Song(1020–1101) dabbled in every known field of science, mathematics, music and statecraft,[38]while others likeOuyang Xiu(1007–1072) orZeng Gong(1019–1083) pioneered ideas in earlyepigraphy,archeologyandphilology.[39][40]

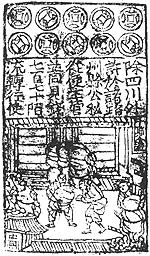

From the 11th to 13th century, the number of exam candidates participating in taking the exams increased dramatically from merely 30,000 to 400,000 by the dynasty's end.[42]Widespread printingthroughwoodblockandmovable typeenhanced the spread of knowledge amongst the literate in society, enabling more people to become candidates and competitors vying for a prestigious degree.[34][43]With a dramatically expanding population matching a growing amount of gentry, while the number of official posts remained constant, the graduates who were not appointed to government would provide critical services in local communities, such as funding public works, running private schools, aiding in tax collection, maintaining order, or writing localgazetteers.[44][45][46][47]

Nóng ( nông / nông )

[edit]

SinceNeolithic times in China,agriculture was a key element to the rise of China's civilization and every other civilization. The food that farmers produced sustained the whole of society, while theland taxexacted on farmers' lots and landholders' property produced much of the state revenue for China's pre-modern ruling dynasties. Therefore, the farmer was a valuable member of society, and even though he was not considered one with theshiclass, the families of theshiwere usually landholders that often produced crops and foodstuffs.[48]

From the ninth century BC (late WesternZhou dynasty) to around the end of theWarring States period,agricultural land was distributed according to thewell-field system( tỉnh điền ), whereby a square area of land was divided into nine identically-sized sections; the eight outer sections ( tư điền;sītián) were privately cultivated by farmers and the center section ( công điền; gōngtián) was communally cultivated on behalf of the landowning aristocrat. When the system became economically untenable in theWarring States period,it was replaced by a system of private land ownership. It was first suspended in the state ofQinbyShang Yangand other states soon followed suit.[49]

From AD 485–763, land was equally distributed to farmers under theequal-field system( đều điền ).[50][51][52]Families were issued plots of land on the basis of how many able men, including slaves, they had; a woman would be entitled to a smaller plot. As government control weakened in the 8th century, land reverted into the hands of private owners.

Song dynasty(950–1279) rural farmers engaged in the small-scale production of wine, charcoal, paper, textiles, and other goods.[53]

By theMing dynasty(1368–1644), the socioeconomic class of farmers grew more and more indistinct from another social class in the four occupations: the artisan. Artisans began working on farms in peak periods and farmers often traveled into the city to find work during times of dearth.[54]The distinction between what was town and country was blurred in Ming China, since suburban areas with farms were located just outside and in some cases within the walls of a city.[54]

Gōng ( công )

[edit]

Artisansand craftsmen—their class identified with theChinese charactermeaninglabour—were much like farmers in the respect that they produced essential goods needed by themselves and the rest of society. Although they could not provide the state with much of its revenues since they often had no land of their own to be taxed, artisans and craftsmen were theoretically respected more than merchants. Since ancient times, the skilled work of artisans and craftsmen was handed down orally from father to son, although the work of architects and structural builders were sometimes codified, illustrated, and categorized in Chinese written works.[55]

Artisans and craftsmen were either government-employed or worked privately. A successful and highly skilled artisan could often gain enough capital in order to hire others as apprentices or additional laborers that could be overseen by the chief artisan as a manager. Hence, artisans could create their own small enterprises in selling their work and that of others, and like the merchants, they formed their ownguilds.[55]

Researchers have pointed to the rise ofwage labourin late Ming and early Qing workshops in textile, paper and other industries,[56][57]achieving large-scale production by using many small workshops, each with a small team of workers under a master craftsman.[56]

Although architects and builders were not as highly venerated as the scholar-officials, there were some architectural engineers who gained wide acclaim for their achievements. One example of this would be theYingzao Fashiprinted in 1103, an architectural building manual written byLi Jie(1065–1110), sponsored byEmperor Huizong(r. 1100–1126) for these government agencies to employ and was widely printed for the benefit of literate craftsmen and artisans nationwide.[58][59]

In the late ofMing dynastythere were many porcelain kilns created that led the Ming dynasty to be economically well off.[60]The Qing emperors like theKangxi Emperorhelped the growth of porcelain export and by allowing an organization of private maritime trade that assisted families who owned private kilns.[61]Chinese export porcelain,designed purely for the European market and unpopular among locals as it lacked the symbolic significance of wares produced for the Chinese home market,[62][63]was a highly popular trade good.[64]

In China, silk-worm farming was originally restricted to women, and many women were employed in the silk-making industry.[65]Even as knowledge ofsilk productionspread to the rest of the world, Song dynasty China was able to maintain near-monopoly on manufacture by large scale industrialization, through the two-person draw loom, commercialized mulberry cultivation, and a factory production.[66]The organization of silk weaving in 18th-century Chinese cities was compared with theputting-out systemused in European textile industries between the 13th and 18th centuries. As the interregional silk trade grew, merchant houses began to organize manufacture to guarantee their supplies, providing silk to households for weaving aspiece work.[67]

Shāng ( thương )

[edit]

In Ancient pre-Imperial China, merchants were highly regarded as necessary for the circulation of essential goods. The legendaryEmperor Shun,prior to receiving the throne from his predecessor, was said to be a merchant. Archaeological artifacts andoracle bonessuggest a high status was accorded to merchant activity. In theSpring and Autumn period,Hegemon of ChinaDuke Huan of QiappointedGuan Zhong,a merchant, as Prime Minister. He cut taxes for merchants, built rest stops for merchants, and encouraged other lords to lower tariffs.[14]

In Imperial China, the merchants, traders, and peddlers of goods were viewed by the scholarly elite as essential members of society, yet were esteemed least of the four occupations in society, due to the view that they were a threat to social harmony from acquiring disproportionally large incomes,[16]market manipulationor exploiting farmers.[68]

However, the merchant class of China throughout all of Chinese history were usually wealthy and held considerable influence above its supposed social standing.[69]The Confucian philosopherXunziencouraged economic cooperation and exchange. The distinction between gentry and merchants was not as clear or entrenched as in Japan and Europe, and merchants were even welcomed by gentry if they abided by Confucian moral duties. Merchants accepted and promoted Confucian society by funding education and charities, and advocating Confucian values of self-cultivation of integrity, frugality, and hard work. By the late imperial period, it was a trend in some regions for scholars to switch to careers as merchants. William Rowe's research of rural elites in late imperial Hanyang, Hubei shows that there was a very high level of overlap and mi xing between the gentry and the merchants.[70]

Han dynasty writers mention merchants owning huge tracts of land.[71]A merchant who owned property worth a thousandcattiesof gold—equivalent to ten million cash coins—was considered a great merchant.[72]Such a fortune was one hundred times larger than the average income of a middle class landowner-cultivator and dwarfed the annual 200,000 cash-coin income of a marquess who collected taxes from a thousand households.[73]Some merchant families made fortunes worth over a hundred million cash, which was equivalent to the wealth acquired by the highest officials in government.[74]Itinerant merchants who traded between a network of towns and cities were often rich as they had the ability to avoid registering as merchants (unlike the shopkeepers),[75]Chao Cuo(d. 154 BC) states that they wore fine silks, rode in carriages pulled by fat horses, and whose wealth allowed them to associate with government officials.[76]

Historians like Yu Yingshi and Billy So have shown that as Chinese society became increasingly commercialized from theSong dynastyonward, Confucianism had gradually begun to accept and even support business and trade as legitimate and viable professions, as long as merchants stayed away from unethical actions. Merchants in the meantime had also benefited from and utilized Confucian ethics in their business practices. By the Song period, merchants often colluded with the scholarly elite; as early as 955, theScholar-officialsthemselves were using intermediary agents to participate in trading.[69]Since the Song government took over several key industries and imposed strict state monopolies, the government itself acted as a large commercial enterprise run by scholar-officials.[81]The state also had to contend with the merchantguilds;whenever the state requisitioned goods and assessed taxes it dealt with guild heads, who ensured fair prices and fair wages via official intermediaries.[82][83]

By the late Ming dynasty, the officials often needed to solicit funds from powerful merchants to build new roads, schools, bridges, pagodas, or engage in essential industries, such as book-making, which aided the gentry class in education for the imperial examinations.[84]Merchants began to imitate the highly cultivated nature and manners of scholar-officials in order to appear more cultured and gain higher prestige and acceptance by the scholarly elite.[85]They even purchased printed books that served as guides to proper conduct and behavior and which promoted merchant morality and business ethics.[86]The social status of merchants rose to such significance[87][88][89]that by the late Ming period, many scholar-officials were unabashed to declare publicly in their official family histories that they had family members who were merchants.[90]The scholar-officials' dependence upon merchants received semi-legal standing when scholar-official Qiu Jun (1420–1495), argued that the state should only mitigate market affairs during times of pending crisis and that merchants were the best gauge in determining the strength of a nation's riches in resources.[91]The Imperial court followed this guideline by granting merchants licenses to trade in salt in return for grain shipments to frontier garrisons in the north.[92]The state realized that merchants could buy salt licenses with silver and in turn boost state revenues to the point where buying grain was not an issue.[92]

Merchants banded in organisations known ashuiguanorgongsuo;pooling capital was popular as it distributed risk and eased the barriers to market entry. They formed partnerships known ashuoji zhi(silent investor and active partner),lianhao zhi(subsidiary companies),jingli fuzhe zhi(owner delegates control to a manager),xuetu zhi(apprenticeship), andhegu zhi(shareholding). Merchants had a tendency to invest their profits in vast swathes of land.[93][94]

Outside China

[edit]Outside of China, the same values permeated and prevailed across other East Asian societies where China exerted considerable influence. Japan and Korea were heavily influenced by Confucian thought that the four occupational social hierarchy in those societies were modeled from that of China's.[95]

Ryukyu Kingdom

[edit]

A similar situation occurred in theRyūkyū Kingdomwith the scholarly class ofyukatchu,but yukatchu status was hereditary and could be bought from the government as the kingdom's finances were frequently deficient.[96]Due to the growth of this class and the lack of government positions open for them,Sai Onallowed yukatchu to become merchants and artisans while keeping their high status.[97]There were three classes of yukatchu, thepechin,satonushiandchikudun,and commoners may be admitted for meritorious service.[98]The Ryukyu Kingdom's capital of Shuri also featured a university and school system, alongside a civil service examination system.[99]The government was managed by theSeissei,Sanshikanand theBugyo(Prime Minister, Council of Ministers and Administrative Departments). Yukatchu who failed the examinations or were otherwise deemed unsuitable for office would be transferred to obscure posts and their descendants would fade into insignificance.[100]Ryukyuan students were also enrolled into the National Academy (Guozi gian) in China, at Chinese government expense, and others studied privately at schools inFu gianprovince such diverse skills as law, agriculture, calendrical calculation, medicine, astronomy, and metallurgy.[101]

Japan

[edit]InJapan,theshirole, unlike the scholars in China, became a hereditary class known as thesamurai,[102]and marriage between people of unequal class was socially unacceptable.[10]Originally a martial class, the samurai became civil administrators to theirdaimyōsduring theTokugawa shogunate.No exams were needed as the positions were inherited. They constituted about 5% of the population and were allowed to have a proper surname. Older scholars believed that there wereShi-nō-kō-shō(Sĩ nông công thương)of "samurai, peasants (hyakushō), craftsmen, and merchants (chōnin) "under the daimyo, with 80% of peasants under the 5% samurai class, followed by craftsmen and merchants.[103]However, various studies have revealed since about 1995 that the classes of peasants, craftsmen, and merchants under the samurai were equal, and the old hierarchy chart has been removed from Japanese history textbooks. In other words, peasants, craftsmen, and merchants are not a social pecking order, but a social classification.[7][8][9]

In the sixteenth century, lords began to centralise administration by replacingenfeoffmentwith stipend grants, and placing pressure on vassals to relocate into castle towns, away from independent power bases. Military commanders became rotated to avert the formation of strong personal loyalties from the troops. Artisans and merchants were solicited by these lords and sometimes received official appointments. This century was a period of exceptional social mobility, with instances of merchants of samurai-descent or commoners becoming samurai. By the eighteenth century samurai and merchants had become interwoven intimately, despite general samurai hostility toward merchants who as their creditors were blamed for the financial difficulties of a debt-ridden samurai class.[104]

Korea

[edit]

InSillaKorea,the scholar-officials, also known as head rank 6, 5, and 4 (두품), were strictly hereditary castes under thebone-rank system(골품제도), and their power was limited by the royal clan who monopolized the positions of importance.[105]

From the late 8th century, succession wars in Silla, as well as frequent peasant uprisings, led to the dismantling of the bone-rank system. Head rank 6 leaders sojourned to China for study, while regional governance fell into thehojokor castle-lords commanding private armies detached from the central regime. These factions coalesced, introducing a new national ideology that was an amalgamation ofChan Buddhism,Confucianism andFeng Shui,laying the foundation for the formation of the new Goryeo Kingdom.King Gwangjong of Goryeointroduced a civil service examination system in 958, andKing Seongjong of Goryeocomplemented it with the establishment of a Confucian-style educational facilities and administration structures, extending for the first time to local areas. However, only aristocrats were permitted to sit for these examinations, and the sons of officials of at least 5th rank were exempt completely.[106]

InJoseonKorea, the Scholar occupation took the form of the nobleyangbanclass, which prevented the lower classes from taking the advancedgwageoexams so they could dominate the bureaucracy. Below the yangban were thechungin,a class of privileged commoners who were petty bureaucrats, scribes, and specialists. The chungin were actually the least populous class, even smaller than the yangban. The yangban constituted 10% of the population.[107]From the mid-Joseon period, military officers and civil officials were separately derived from different clans.[108]

Vietnam

[edit]

Vietnamese dynasties also adopted the examination degree system (khoa bảng khoa bảng ) to recruit scholars for government service.[109][110][111][112][113]The bureaucrats were similarly divided into nine grades and six ministries, and examinations were held annually at provincial level, and triennially at regional and national levels.[114]The Vietnamese political elite consisted of educated landholders whose interests often clashed with the central government. Although all land theoretically was the ruler's, and was supposed to be distributed equitably by theequal-field system(chế độ Quân điền) and non-transferable, the court bureaucracy increasingly appropriated land which they leased to tenant farmers and hired labourers to till.[115]It was unlikely for individuals of common background to become Mandarins, however, since they lacked access to classical education. Degree-holders were frequently clustered in certain clans.[116]

Maritime Southeast Asia

[edit]

Chinese official positions, under various different native titles, go back to the courts of precolonial states ofSoutheast Asia,such as theSultanates of MalaccaandBanten,and theKingdom of Siam.With the consolidation of colonial rule, these became part of the civil bureaucracy in Portuguese, Dutch and British colonies, exercising both executive and judicial powers over local Chinese communities under the colonial authorities,[117][118][119]examples being the title ofChao Praya Chodeuk Rajasrethiin Thailand'sChakri dynasty,[120]andSri Indra Perkasa Wijaya Bakti,the Malay court position ofKapitan Cina Yap Ah Loy,arguably the founder of modernKuala Lumpur.[121]

Overseas Chinese merchant families inBritish Malayaand theDutch Indiesdonated generously to the provision of defence and disaster relief programs in China in order to receive nominations to the Imperial Court for honorary official ranks. These ranged fromchün-hsiu,a candidate for the Imperial examinations, tochih-fu(Chinese:Tri phủ;pinyin:zhīfŭ) ortao-t'ai(Chinese:Đạo đài;pinyin:dàotái), prefect and circuit intendant respectively. The bulk of these sinecure purchases were at the level oft'ungchih(Chinese:Đồng tri;pinyin:tóngzhī), or sub-prefect, and below. Garbing themselves in the official robes of their rank in most ceremonial functions, these wealthy dignitaries would adopt the conduct of scholar-officials. Chinese language newspapers would list them exclusively as such and precedence at social functions would be determined by title.[122]

Incolonial Indonesia,the Dutch government appointedChinese officers,who held the ranks ofMajoor,KapiteinorLuitenant der Chinezenwith legal and political jurisdiction over the colony's Chinese subjects.[123]The officers were overwhelmingly recruited from old families of the 'Cabang Atas' or the Chinese gentry of colonial Indonesia.[124]Although appointed without state examinations, the Chinese officers emulated thescholar-officialsof Imperial China, and were traditionally seen locally as upholders of the Confucian social order and peaceful coexistence under the Dutch colonial authorities.[123]For much of its history, appointment to the Chinese officership was determined by family background, social standing and wealth, but in the twentieth century, attempts were made to elevate meritorious individuals to high rank in keeping with the colonial government's so-calledEthical Policy.[123]

The merchant and labour partnerships of China developed into theKongsiFederations across Southeast Asia, which were associations of Chinese settlers governed through direct democracy.[125]OnKalimantanthey established sovereign states, theKongsi republicssuch as theLanfang Republic,which bitterly resisted Dutch colonisation in theKongsi Wars.[126]

Unclassified occupations

[edit]

There were many social groups that were excluded from the four broad categories in the social hierarchy. These included soldiers and guards, religious clergy and diviners, eunuchs and concubines, entertainers and courtiers, domestic servants and slaves, prostitutes, and low class laborers other than farmers and artisans. People who performed such tasks that were considered either worthless or "filthy" were placed in the category of mean people ( tiện nhân ), not being registered as commoners or having some legal disabilities.[1]

Imperial clan

[edit]The emperor—embodying aheavenly mandateto judicial and executive authority—was on a social and legal tier above thegentryand theexam-draftedscholar-officials.Under the principle of the Mandate of Heaven, the right to rule was based on "virtue"; if a ruler was overthrown, this was interpreted as an indication that the ruler was unworthy, and had lost the mandate, and there would often be revolts following major disasters as citizens saw these as signs that the Mandate of Heaven had been withdrawn.[127]

The Mandate of Heaven does not require noble birth, depending instead on just and able performance. TheHanandMing dynastieswere founded by men of common origins.[128][129]

Although his royal family and noble extended family were also highly respected, they did not command the same level of authority.

During the initial and end phases of theHan dynasty,theWestern Jin dynasty,and theNorthern and Southern dynasties,the members of the Imperial clan were enfeoffed with vassal states, controlling military and political power: they often usurped the throne, intervened in Imperial succession, or fought civil wars.[130]From the 8th century on, theTang dynastyimperial clan was restricted to the capital and denied fiefdoms, and by theSong dynastywere also denied any political power. By theSouthern Song dynasty,imperial princes were assimilated into the scholars, and had to take the imperial examinations to serve in government, like commoners. TheYuan dynastyfavoured the Mongol tradition of distributing Khanates, and under this influence, theMing dynastyalso revived the practice of granting titular "kingdoms" to Imperial clan members, although they were denied political control;[131]only near the end of the dynasty were some permitted to partake in the examinations to qualify for government service as common scholars.[132]

Eunuchs

[edit]

The courteunuchswho served the royals were also viewed with some suspicion by the scholar-officials, since there were several instances in Chinese history where influential eunuchs came to dominate the emperor, his imperial court, and the whole of the central government. In an extreme example, the eunuchWei Zhongxian(1568–1627) had his critics from the orthodox Confucian 'Donglin Society' tortured and killed while dominating the court of theTianqi Emperor—Wei was dismissed bythe next rulerand committed suicide.[133]In popular culture texts such as Zhang Yingyu'sThe Book of Swindles(c. 1617), eunuchs were often portrayed in starkly negative terms as enriching themselves through excessive taxation and indulging in cannibalism and debauched sexual practices.[134]The eunuchs at the Forbidden City during the later Qing period were infamous for their corruption, stealing as much as they could.[135]The position of eunuch at the Forbidden City offered such opportunities for theft and corruption that countless men willingly become eunuchs in order to live a better life.[135]Ray Huangargues that eunuchs represented the personal will of the Emperor, while the officials represented the alternate political will of thebureaucracy.The clash between them would thus have been a clash of ideologies or political agenda.[136]

Religious workers

[edit]

Althoughshamansand diviners inBronze AgeChina had some authority as religious leaders in society, as government officials during the earlyZhou dynasty,[137]with theShang dynastyKings sometimes described as shamans,[138][139]and may have been the original physicians, providing elixirs to treat patients,[140]ever since Emperor Wu of Han established Confucianism as the state religion, the ruling classes have shown increasing prejudice against shamanism,[141]preventing them from amassing too much power and influence like military strongmen (one example of this would beZhang Jiao,who led aTaoistsect intoopen rebellionagainst the Han government's authority[142]).

Fortune-tellers such as geomancers and astrologers were not highly regarded.[143]

Buddhistmonkhood grew immensely popular from the fourth century, where the monastic life's exemption from tax proved alluring to poor farmers. 4,000 government-funded monasteries were established and maintained through the medieval period, eventually leading tomultiple persecutions of Buddhism in China,a lot of the contention being over Buddhist monasteries' exemption from government taxation,[144]but also because laterNeo-Confucianscholars saw Buddhism as an alien ideology and threat to the moral order of society.[145]

However from the fourth to twentieth centuries, Buddhist monks were frequently sponsored by the elite of society, sometimes even by Confucian scholars, with monasteries described as "in size and magnificence no prince's house could match".[146]Despite the strong Buddhist sympathies of theSui dynastyandTang dynastyrulers, the curriculum of theImperial Examinationswas still defined by Confucian canon as it alone covered political and legal policy necessary to government.[147]

Military

[edit]

The social category of the soldier was left out of the social hierarchy due to the gentry scholars'embracing of intellectual cultivation ( văn wén) and detest for violence ( võ wǔ).[148]The scholars did not want to legitimize those whose professions centered chiefly around violence, so to leave them out of the social hierarchy altogether was a means to keep them in an unrecognized and undistinguished social tier.[148]

Soldiers were not highly respected members of society,[48]specifically from the Song dynasty onward, due to the newly instituted policy of "Emphasizing the civil and downgrading the military" (Chinese:Trọng văn khinh võ).[149]Soldiers traditionally came from farming families, while some were simply debtors who fled their land (whether owned or rented) to escape lawsuits by creditors or imprisonment for failing to pay taxes.[48]Peasants were encouraged to join militias such as theBaojia( bảo giáp ) orTuanlian( đoàn luyện ),[150]but full-time soldiers were usually hired from amnestied bandits or vagabonds, and peasant militia were generally regarded as the more reliable.[148][151][152]

From the 2nd century BC onward, soldiers along China's frontiers were also encouraged by the state to settle down on their own farm lots in order for the food supply of the military to become self-sufficient, under the Tuntian system ( đồn điền ),[153]the Weisuo system ( vệ sở ) and theFubing system( phủ binh ).[154][155]Under these schemes, multiple dynasties attempted to create a hereditary militarycasteby exchanging border farmland or other privileges for service. However, in every instance, the policy would fail due to rampant desertion caused by the extremely low regard for violent occupations, and subsequently these armies had to be replaced with hired mercenaries or even peasant militia.[148][156]

However, for those without formal education, the quickest way to power and the upper echelons of society was to join the military.[157][158]Although the soldier was looked upon with a bit of disdain by scholar-officials and cultured people, military officers with successful careers could gain a considerable amount of prestige.[159]Despite the claim of moral high ground, scholar-officials often commanded troops and wielded military power.[148]

Entertainers

[edit]Entertaining was considered to be of little use to society and was usually performed by theunderclassknown as the "mean people" (Chinese:Tiện dân).[17]

Entertainers and courtiers were often dependents upon the wealthy or were associated with the often-perceived immoral pleasure grounds of urban entertainment districts.[160]Musicians who played music as full-time work were of low status.[161]To give them official recognition would have given them more prestige.

"Proper" music was considered a fundamental aspect of nurturing of character and good government, but vernacular music, as defined as having "irregular movements" was criticised as corrupting for listeners. In spite of this, Chinese society idolized many musicians, even women musicians (who were seen as seductive) such asCai Yan(c. 177) andWang Zhaojun(40–30 BC).[162]Musical abilities were a prime consideration in marriage desirability.[163]During the Ming dynasty, female musicians were so common that they even played for imperial rituals.[163]

Private theatre troupes in the homes of wealthy families were a common practice.[163]

Professional dancers of the period were of low social status and many entered the profession through poverty, although some such as Zhao Feiyan achieved higher status by becoming concubines. Another dancer was Wang Wengxu (Vương ông cần) who was forced to become a domestic singer-dancer but who later bore the futureEmperor Xuan of Han.[164][165]

Institutions were set up to oversee the training and performances of music and dances in the imperial court, such as the Great Music Bureau ( quá nhạc thự ) and the Drums and Pipes Bureau ( cổ xuý thự ) responsible for ceremonial music.[166]Emperor Gaozuset up theRoyal Academy,whileEmperor Xuanzongestablished thePear Garden Academyfor the training of musicians, dancers and actors.[167]There were around 30,000 musicians and dancers at the imperial court during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong,[168]with most specialising inyanyue.All were under the administration of the Drums and Pipes Bureau and an umbrella organization called the Taichang Temple ( Thái Thường Tự ).[169]

Professional artists had similarly low status.[143]

Slaves

[edit]

Slavery was comparatively uncommon in Chinese history but was still practiced, largely as a judicial punishment for crimes.[170][171][172]In the Han and Tang dynasties, it was illegal to trade in Chinese slaves (that were not criminals), but foreign slaves were acceptable.[173][174]TheXin dynastyemperorWang Mang,the Ming dynastyHongwuemperor, and Qing dynastyYongzhengemperor attempted to ban slavery entirely but were not successful.[172][175][176]Illegal enslavement of children frequently occurred under the guise of adoption from poor families.[173]It has been speculated by researchers such as Sue Gronewold that up to 80% of late Qing era prostitutes may have been slaves.[177]

Six dynasties,Tang dynasty, and to a partial extent Song dynasty society also contained a complex system of servile groups included under "mean people" ( tiện nhân ) that formed intermediate standings between the four occupations and outright slavery. These were, in descending order:[17]

- the musicians of the Imperial Sacrifices quá thường âm thanh người

- general bondsmen tạp hộ, including Imperial tomb guards

- musician households kỹ nữ

- official bondsmen quan hộ

- government slaves nô tỳ

And in private service,

- personal retainers bộ khúc

- female retainers khách nữ

- private slaves gia nô

These performed a wide assortment of jobs in households, in agriculture, delivering messages or as private guards.[17]

See also

[edit]- Social structure of China

- Edo society

- Estates of the realm

- Society and culture of the Han dynasty

- Society of the Song dynasty

- Yangban,Chungin,SangminandCheonminin Korea

- Youxia

- Kheshig

- Samurai

- Hwarang

Notes

[edit]- ^abcdHansson, pp. 20-21

- ^Brook, 72.

- ^abFairbank, 108.

- ^ab(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

Cổ giả có tứ dân: Có sĩ dân, có thương dân, có nông dân, có công dân. Phu giáp, phi mỗi người chỗ có thể vì cũng. Khâu làm giáp, phi chính cũng.

- ^ab(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

Nông nông, sĩ sĩ, công công, thương thương

- ^abByres, Terence; Mukhia, Harbans (1985).Feudalism and Non European Societies.London:Frank Cass and Co.pp. 213, 214.ISBN0-7146-3245-7.

- ^ab“Sĩ nông công thương” や “Tứ dân bình đẳng” の dùng từ が sử われていないことについて.Tokyo Shoseki(in Japanese). Archived fromthe originalon 30 November 2023.Retrieved7 March2024.

- ^abĐệ 35 hồi sách giáo khoa から『 sĩ nông công thương 』が tiêu えた ー sau biên ー lệnh cùng 3 năm quảng báo うき “ウキカラ” 8 nguyệt hào.Uki, Kumamoto(in Japanese). Archived fromthe originalon 30 August 2023.Retrieved7 March2024.

- ^abNgười 権 ý thức の アップデート(PDF).Shimonoseki(in Japanese). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 June 2023.Retrieved7 March2024.

- ^abGeorge De Vos and Hiroshi Wagatsuma (1966).Japan's invisible race: caste in culture and personality.University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-00306-4.

- ^Toby Slade (2009).Japanese Fashion: A Cultural History.Berg.ISBN978-1-84788-252-3.

- ^abcdeBarbieri-Low (2007), 37.

- ^Barbieri-Low (2007), 36–37.

- ^abTang, Li xing (2017). "1".Merchants and Society in Modern China: Rise of Merchant Groups China Perspectives.Routledge.ISBN978-1351612999.

- ^(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

Xuân thu rằng: Tứ dân đều tắc vương đạo hưng mà bá tánh ninh; cái gọi là tứ dân giả, sĩ, nông, công, thương cũng.

- ^abKuhn, Philip A. (1984).Chinese views of social classification, in James L. Watson, Class and Social stratification in post-Revolution China.Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–21.ISBN0521143845.

- ^abcdeHansson, 28-30

- ^Gernet, 129–130.

- ^abEbrey (2006), 22.

- ^abcPeers, pp. 17, 20, 24, 31

- ^.(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

Đem chú báo . tắc quan rồi . rằng . bình công chi linh . thượng phụ tương dư . báo bắn ra ở giữa . đem chú . tắc lại quan rồi . rằng . không hiệp bỉ . trừu thỉ . thành bắn chi . ế . trương cái trừu thù mà xuống . bắn chi . chiết cổ . đỡ phục mà đánh chi . chiết chẩn . lại bắn chi . chết .

- ^(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

Tấn người hoặc lấy quảng đội . không thể tiến . sở người kị chi thoát quynh . thiếu tiến . mã còn . lại kị chi rút bái đầu hành . bèn xuất núi

- ^Ebrey (2006), 29–30.

- ^Ebrey (2006), 32.

- ^Ebrey (2006), 32–39.

- ^"China's First Empire | History Today".historytoday.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2017.Retrieved17 April2017.

- ^World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, p. 36

- ^Borthwick 2006, pp. 9–10

- ^Loewe, Michael (1994-09-15).Divination, Mythology and Monarchy in Han China.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-45466-7.

- ^Creel, H.G. (1949). Confucius: The Man and the Myth. New York: John Day Company. pp. 239–241

- Creel, H.G. 1960. pp. 239–241. Confucius and the Chinese Way

- Creel, H.G. 1970, What Is Taoism?, 86–87

- Xinzhong Yao 2003. p. 231. The Encyclopedia of Confucianism: 2-volume Set.https://books.google /books?id=P-c4CQAAQBAJ&pg=PA231

- Griet Vankeerberghen 2001 pp. 20, 173. The Huainanzi and Liu An's Claim to Moral Authority.https://books.google /books?id=zt-vBqHQzpQC&pg=PA20

- ^Michael Loewe pp. 145, 148. 2011. Dong Zhongshu, a ‘Confucian’ Heritage and the Chunqiu Fanlu.https://books.google /books?id=ZQjJxvkY-34C&pg=PA145

- ^Edward A Kracke Jr, Civil Service in Early Sung China, 960-1067, p 253

- ^Ebrey (1999), 145–146.

- ^abEbrey (2006), 159.

- ^Gernet, 172.

- ^Ebrey et al.,East Asia,167.

- ^Yuan, 193–199.

- ^Ebrey et al.,East Asia,162–163.

- ^Ebrey,Cambridge Illustrated History of China,148.

- ^Fraser & Haber, 227.

- ^"A Chinese School".Wesleyan Juvenile Offering.IV:108. October 1847.Retrieved17 November2015.

- ^Ebrey (2006), 160.

- ^Fairbank, 94.

- ^Fairbank, 104.

- ^Fairbank, 101–106.

- ^Michael, 420–421.

- ^Hymes, 132–133.

- ^abcGernet, 102–103.

- ^Zhufu, Fu (1981), "The economic history of China: Some special problems",Modern China,7(1): 7,doi:10.1177/009770048100700101,S2CID220738994

- ^Charles Holcombe (2001).The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. – A.D. 907.University of Hawaii Press. pp. 136–.ISBN978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^David Graff (2003).Medieval Chinese Warfare 300–900.Routledge. pp. 140–.ISBN978-1-134-55353-2.

- ^Dr R K Sahay (2016).History of China's Military.Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 103–.ISBN978-93-86019-90-5.

- ^Ebrey,Cambridge Illustrated History of China,141.

- ^abSpence, 13.

- ^abGernet, 88–94

- ^abFaure, David (2006),China and capitalism: a history of business enterprise in modern China,Understanding China: New Viewpoints on History And Culture, Hong Kong University Press, pp. 17–18,ISBN978-962-209-784-1

- ^Rowe, William T.(1978–2020). "Social stability and social change". InFairbank, John K.;Twitchett, Denis(eds.).The Cambridge History of China.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.p. 526.

- ^Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 84.

- ^Guo, 4–6.

- ^Medley, Margaret (1987). "The Ming – Qing Transition in Chinese Porcelain".Arts Asiatiques.42:65–76.doi:10.3406/arasi.1987.1217.JSTOR43486524.

- ^Zhao, Gang (2013).The Qing Opening to the Ocean: Chinese Maritime Policies, 1684–1757.University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 116–136.

- ^Newton, Bettina (2014). "14".Beginner's Guide To Antique Collection.Karan Kerry.Retrieved6 January2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^Burton, William (1906)."The Letters of Père D'Entrecolles".Porcelain: its nature art and manufacture.London: B. T. Batsford Ltd. Archived fromthe originalon 23 September 2015.Retrieved5 January2015.

- ^Valenstein, Susan G. (1989).A handbook of Chinese ceramics.New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 197.ISBN0-87099-514-6.

- ^Federico, Giovanni (1997).An Economic History of the Silk Industry, 1830–1930.Cambridge university Press. pp. 14, 20.ISBN0521581982.

- ^Heleanor B. Feltham:Justinian and the International Silk Trade,p. 34

- ^Li, Lillian M. (1981),China's silk trade: traditional industry in the modern world, 1842–1937,Harvard East Asian monographs, vol. 97, Harvard Univ Asia Center, pp. 50–52,ISBN978-0-674-11962-8

- ^(in Chinese) – viaWikisource.

Này thương công chi dân, tu trị khổ dũ chi khí, tụ phất mĩ chi tài, súc tích đãi khi, mà mâu nông phu chi lợi.

- ^abGernet, Jacques (1962).Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276.Translated by H.M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press.ISBN0-8047-0720-0pp. 68–69

- ^Guo Wu (2010).Zheng Guanying: Merchant Reformer of Late Qing China and His Influence on Economics, Politics, and Society.Cambria Press. pp. 14–16.ISBN978-1604977059.

- ^Ch'ü (1969), 113–114.

- ^Ch'ü (1972), 114.

- ^Ch'ü (1972), 114–115.

- ^Ch'u (1972), 115–117.

- ^Nishijima (1986), 576.

- ^Nishijima (1986), 576–577; Ch'ü (1972), 114; see also Hucker (1975), 187.

- ^Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais (2006), 156.

- ^Bowman (2000), 105.

- ^Peter Bernholz (2003).Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships.Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 53.ISBN978-1-84376-155-6.

- ^Daniel R. Headrick (1 April 2009).Technology: A World History.Oxford University Press. p. 85.ISBN978-0-19-988759-0.

- ^Gernet, 77.

- ^Gernet, 88.

- ^Ebrey et al.,East Asia,157.

- ^Brook, 90–93, 129–130, 151.

- ^Brook, 128–129, 134–138.

- ^Brook, 215–216.

- ^Yu Yingshi dư anh khi,Zhongguo Jinshi Zongjiao Lunli yu Shangren JingshenTrung Quốc cận đại tôn giáo luân lý cùng thương nhân tinh thần. (Taipei: Lianjing Chuban Shiye Gongsi, 1987).

- ^Billy So,Prosperity, Region, and Institutions in Maritime China.(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 253–279.

- ^Billy So, “Institutions in market economies of premodern maritime China.” In Billy So ed.,The Economy of Lower Yangzi Delta in Late Imperial China.(New York: Routledge, 2013), 208–232.

- ^Brook, 161

- ^Brook, 102.

- ^abBrook, 108.

- ^Tang, Li xing (2017). "2".Merchants and Society in Modern China: Rise of Merchant Groups China Perspectives.Routledge.ISBN978-1351612999.

- ^Fang Liufang; Xia Yuantao; Sang Binxue; Danian Zhang (1989). "Chinese Partnership".Law and Contemporary Problems: The Emerging Framework of Chinese Civil Law: [Part 2].52(3).

- ^Ho, Kwon Ping; De Meyer, Arnoud (2017).The Art of Leadership: Perspectives from Distinguished Thought Leaders.World Scientific Publishing.ISBN978-9813233485.

- ^Smits, 73.

- ^Steben, 47.

- ^Kerr, George H. (2011).Okinawan: The History of an Island People.Tuttle.ISBN978-1462901845.

- ^Smits, Gregory (1999).Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics.University of Hawaii Press. p. 14.ISBN0824820371.

- ^Kerr, George H. (1953).Ryukyu Kingdom and Province Before 1945 (Scientific investigations in the Ryukyu Islands).National Academies.

- ^Smits, Gregory (1999).Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics.University of Hawaii Press. pp. 38–39.ISBN0824820371.

- ^David L. Howell (2005).Geographies of identity in nineteenth-century Japan.University of California Press.ISBN0-520-24085-5.

- ^Beasley 1972,p. 22

- ^Totman, Conrad (1981).Japan Before Perry: A Short History(illustrated ed.). University of California Press. pp.139–140, 161–163.ISBN0520041348.

- ^Lee, Ki-Baik (1984).A New History of Korea.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 50–51.ISBN0-674-61576-X.

- ^신형식 (2005). "1-2".A Brief History of Korea, Volume 1 A Brief History of Korea Volume 1 of The spirit of Korean cultural roots Volume 1 of Uri munhwa ŭi ppuri rŭl chʻajasŏ(illustrated, reprint ed.). Ewha Womans University Press.ISBN8973006193.

- ^Nahm, Andrew C (1996).Korea: Tradition and Transformation — A History of the Korean People(second ed.). Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International. pp. 100–102.ISBN1-56591-070-2.

- ^Seth, Michael J. (2010).A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present.Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 165–167.ISBN9780742567177.

- ^John Kleinen Facing the Future, Reviving the Past: A Study of Social Change in... – 1999 – Page 71

- ^Truong Buu Lâm, New lamps for old: the transformation of the Vietnamese... -Institute of Southeast Asian Studies – 1982 Page 11- "The provincial examinations consisted of three to four parts which tested the following areas: knowledge of the Confucian texts... The title of cu nhan or" person presented "(for office) was conferred on those who succeeded in all four tests."

- ^D. W. Sloper, Thạc Cán Lê Higher Education in Vietnam: Change and Response – 1995 Page 45 "For those successful in the court competitive examination four titles were awarded: trang nguyen, being the first- rank doctorate and first laureate, bang nhan, being a first-rank doctorate and second laureate; tham hoa, being a first-rank..."

- ^Nguyẽn Khá̆c Kham, Yunesuko Higashi An introduction to Vietnamese culture Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) 1967 – Page 20 "The classification became more elaborate in 1247 with the Tam-khoi which divided the first category into three separate classes: Trang-nguyen (first prize winner in the competitive examination at the king's court), Bang-nhan (second prize..."

- ^Walter H. Slote, George A. De Vos Confucianism & the Family 998 – Page 97 "1428–33) and his collaborators, especially Nguyen Trai (1380–1442) — who was himself a Confucianist — accepted... of Trang Nguyen (Zhuang Yuan, or first laureate of the national examination with the highest recognition in every copy)."

- ^SarDesai, D R (2012). "2".Southeast Asia: Past and Present(7 reprint ed.). Hachette UK.ISBN978-0813348384.

- ^John Kleinen Facing the Future, Reviving the Past: A Study of Social Change in... – 1999 – Page 5, 31-32

- ^Woodside, Alexander; American Council of Learned Societies (1988).Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century ACLS Humanities E-Book Volume 140 of East Asian Monograph Series Harvard East Asian monographs, ISSN 0073-0483 Volume 52 of Harvard East Asian series History e-book project(illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Harvard Univ Asia Center. p.216.ISBN067493721X.

- ^Ooi, Keat Gin.Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, From Angkor Wat to East Timor,p. 711

- ^Hwang, In-Won.Personalized Politics: The Malaysian State Under Matahtir,p. 56

- ^Buxbaum, David C.; Association of Southeast Asian Institutions of Higher Learning (2013).Family Law and Customary Law in Asia: A Contemporary Legal Perspective.Springer.ISBN9789401762168.Retrieved30 March2018.

- ^"The Siamese Aristocracy".Soravij.Retrieved9 January2017.

- ^Malhi, PhD., Ranjit Singh (May 5, 2017)."The history of Kuala Lumpur's founding is not as clear cut as some think".thestar.my.The Star. The Star Online.Retrieved23 May2017.

- ^Godley, Michael R. (2002).The Mandarin-Capitalists from Nanyang: Overseas Chinese Enterprise in the Modernisation of China 1893-1911 Cambridge Studies in Chinese H Cambridge Studies in Chinese History, Literature and Institutions.Cambridge University Press. pp.41–43.ISBN0521526957.

- ^abcLohanda, Mona (1996).The Kapitan Cina of Batavia, 1837-1942: A History of Chinese Establishment in Colonial Society.Jakarta: Djambatan.ISBN9789794282571.Retrieved21 November2018.

- ^Haryono, Steve (2017).Perkawinan Strategis: Hubungan Keluarga Antara Opsir-opsir Tionghoa Dan 'Cabang Atas' Di Jawa Pada Abad Ke-19 Dan 20.Steve Haryono.ISBN9789090302492.Retrieved21 November2018.

- ^Wang, Tai Peng (1979). "The Word" Kongsi ": A Note".Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.52(235): 102–105.JSTOR41492844.

- ^Heidhues, Mary Somers (2003).Golddiggers, Farmers, and Traders in the "Chinese Districts" of West Kalimantan, Indonesia.Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications.ISBN978-0-87727-733-0.

- ^Szczepanski, Kallie."What Is the Mandate of Heaven in China?".About Education.RetrievedApril 4,2024.

- ^"Gaozu Emperor of Han Dynasty".Encyclopædia Britannica.21 March 2024.

- ^Mote, Frederick W.;Twitchett, Denis,eds. (1988).The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.p. 11.ISBN978-0-521-24332-2.

- ^Wang, R.G., p. xx

- ^Wang, R.G. p. xxi

- ^Wang, R.G. p. 10

- ^Spence, 17–18.

- ^Zhang Yingyu,The Book of Swindles: Selections from a Late Ming Collection,translated by Christopher Rea and Bruce Rusk (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

- ^abBehr, EdwardThe Last EmperorLondon: Futura, 1987 page 73.

- ^Huang, Ray (1981).1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline.New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN0-300-02518-1.

- ^Von Falkenhausen, Lothar (1995).Reflections of the Political Role of Spirit Mediums in Early China: The Wu Officials in the Zhou Li, volume 20.Society for the study of Early China. pp. 282, 285.

- ^Chang, Kwang-Chih (1983).Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China.Harvard University Press. pp. 45–47.

- ^Chen, Mengjia (1936).Đời Thương thần thoại cùng vu thuật [Myths and Magic of the Shang Dynasty].Yanjing xuebao Yến Kinh học báo. p. 535.ISBN9787101112139.

- ^Schiffeler, John Wm. (1976). "The Origin of Chinese Folk Medicine".Asian Folklore Studies.35(2). Asian Folklore Studies 35.1: 27.doi:10.2307/1177648.JSTOR1177648.PMID11614235.

- ^Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1892–1910).The Religious System of China: Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect, Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Connected Therewith.Brill Publishers. pp. 1233–1242.

- ^de Crespigny, Rafe(2007).A biographical dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD).Leiden: Brill. p. 1058.ISBN978-90-04-15605-0.

- ^abHui chen, Wang Liu (1959).The Traditional Chinese Clan Rules.Association for Asian Studies. pp. 160–163.

- ^Gernet, Jacques. Verellen, Franciscus.Buddhism in Chinese Society.1998. pp. 14, 318-319

- ^Wright, 88–94.

- ^Brook, Timothy (1993).Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China.Harvard University Press. pp. 2–3.ISBN0674697758.

- ^Wright, 86

- ^abcdeFairbank, 109.

- ^Peers, p. 128

- ^Peers, pp. 114, 130

- ^Peers, pp. 128-130,180,199

- ^Swope, Kenneth M. (2009).The Military Collapse of China's Ming dynasty.Routledge. p. 21.

- ^Theobald, Ulrich."Tuntian".China knowledge.

- ^Liu, Zhaoxiang; et al. (2000).History of Military Legal System.Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House.ISBN7-5000-6303-2.

- ^Peers, pp. 110-112

- ^Peers, pp. 175-179

- ^Lorge, 43.

- ^Ebrey et al.,East Asia,166.

- ^Graff, 25–26

- ^Jones, Andrew F. (2001).Yellow Music: Media Culture and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age.Duke University Press. p.29.ISBN0822326949.

the social status of professional musicians china.

- ^Nettl, Bruno; Rommen, Timothy (2016).Excursions in World Music.Taylor & Francis. p. 131.ISBN978-1317213758.

- ^Ko, Dorothy; Kim, JaHyun; Pigott, Joan R. (2003).Women and Confucian Cultures in Premodern China, Korea, and Japan.University of california press. pp. 112–114.ISBN0520231384.

- ^abcKo, Dorothy; Kim, JaHyun; Pigott, Joan R. (2003).Women and Confucian Cultures in Premodern China, Korea, and Japan.University of california press. pp. 97–99.ISBN0520231384.

- ^Selina O'Grady (2012).And Man Created God: Kings, Cults and Conquests at the Time of Jesus.Atlantic Books. p. 142.ISBN978-1843546962.

- ^"《 Triệu Phi Yến bổ sung lý lịch 》".Chinese Text Project.Original text: Triệu Hậu eo cốt tinh tế, thiện củ bước mà đi, nếu nhân thủ cầm hoa chi, run run nhiên, người khác mạc nhưng học cũng.

- ^Sharron Gu (2011).A Cultural History of the Chinese Language.McFarland. pp. 24–25.ISBN978-0786466498.

- ^Tan Ye (2008).Historical Dictionary of Chinese Theater.Scarecrow Press. p. 223.ISBN978-0810855144.

- ^Dillon, Michael (24 February 1998).China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary.Routledge. pp. 224–225.ISBN978-0700704392.

- ^China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization.City University of Hong Kong Press. 2007. pp. 458–460.ISBN978-9629371401.

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica, inc (2003).The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 27.Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 289.ISBN0-85229-961-3.Retrieved2011-01-11.

- ^The First Emperor of China by Li Yu-Ning(1975)

- ^abHallet, Nicole. "China and Antislavery".Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition,Vol. 1, p. 154 – 156. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007.ISBN0-313-33143-X.

- ^abHansson, p. 35

- ^Schafer, Edward H. (1963),The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics,University of California Press, pp. 44–45

- ^ Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition.Greenwood Publishing Group. 2011. p. 155.ISBN978-0-313-33143-5.

- ^Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion,p. 420, atGoogle Books

- ^Gronewold, Sue (1982).Beautiful merchandise: Prostitution in China, 1860-1936.Women and History. pp. 12–13, 32.

References

[edit]- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. (2007).Artisans in Early Imperial China.Seattle & London: University of Washington Press.ISBN0-295-98713-8.

- Beasley, William G.(1972),The Meiji Restoration,Stanford, California:Stanford University Press,ISBN0-8047-0815-0

- Brook, Timothy.(1998).The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China.Berkeley: University of California Press.ISBN0-520-22154-0

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley,Anne Walthall,James Palais.(2006).East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History.Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.ISBN0-618-13384-4.

- __________. (1999).The Cambridge Illustrated History of China.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-66991-X(paperback).

- Fairbank, John Kingand Merle Goldman (1992).China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition(2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.ISBN0-674-01828-1

- Gernet, Jacques (1962).Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276.Translated by H. M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press.ISBN0-8047-0720-0

- Michael, Franz. "State and Society in Nineteenth-Century China",World Politics: A Quarterly Journal of International Relations(Volume 3, Number 3, April 1955): 419–433.

- Smits, Gregory (1999). "Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics". Honolulu:University of Hawai'i Press.

- Spence, Jonathan D.(1999).The Search For Modern China;Second Edition.New York:W. W. Norton & Company.ISBN0-393-97351-4(Paperback).

- Steben, Barry D. "The Transmission of Neo-Confucianism to the Ryukyu (Liuqiu) Islands and its Historical Significance".

- Wright, Arthur F.(1959).Buddhism in Chinese History.Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Yuan, Zheng. "Local Government Schools in Sung China: A Reassessment",History of Education Quarterly(Volume 34, Number 2; Summer 1994): 193–213.

- Lorge, Peter (2005). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795: 1st Edition. New York: Routledge.

- Wang, Richard G. (2008), "The Ming Prince and Daoism: Institutional Patronage of an Elite" OUP USA,ISBN0199767688

- Peers, C.J., Soldiers of the Dragon, Osprey, New YorkISBN1-84603-098-6

- Hansson, Anders, Chinese Outcasts: Discrimination and Emancipation in Late Imperial China 1996, BRILLISBN9004105964