French Republican calendar

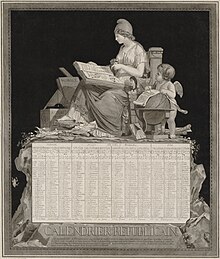

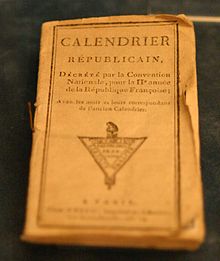

TheFrench Republican calendar(French:calendrier républicain français), also commonly called theFrench Revolutionary calendar(calendrier révolutionnaire français), was acalendarcreated and implemented during theFrench Revolution,and used by the French government for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days by theParis Communein 1871, and meant to replace theGregorian calendar.[1]

The calendar consisted of twelve 30-day months, each divided into three 10-day cycles similar to weeks, plus five or sixintercalary daysat the end to fill out the balance of asolar year.It was designed in part to remove all religious androyalistinfluences from the calendar, and it was part of a larger attempt atdecimalisationin France (which also includeddecimal timeof day,decimalisationof currency, andmetrication). It was used in government records in France and other areas under French rule, includingBelgium,Luxembourg,and parts of theNetherlands,Germany,Switzerland,Malta,andItaly.

Beginning and ending[edit]

TheNational Constituent Assemblyat first intended to create a new calendar marking the "era of Liberty", beginning on 14 July 1789, the date of theStorming of the Bastille.However, on 2 January 1792 its successor theLegislative Assemblydecided that Year IV of Liberty had begun the day before. Year I had therefore begun on 1 January 1789.

On 21 September 1792, theFrench First Republicwasproclaimed,and the newNational Conventiondecided that 1792 was to be known as Year I of the French Republic. It decreed on 2 January 1793 that Year II of the Republic had begun the day before. However, the new calendar as adopted by the Convention in October 1793 made 22 September 1792 the first day of Year I.

Ultimately, the calendar came to commemorate the Republic, and not the Revolution. The Common Era, commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, was abolished and replaced withl'ère républicaine,the Republican Era, signifying the "age of reason" overcoming superstition, as part of the campaign ofdechristianization.

The First Republic ended with thecoronation of Napoleon I as Emperoron 11 Frimaire, Year XIII, or 2 December 1804. Despite this, the republican calendar continued to be used until 1 January 1806, when Napoleon declared it abolished. It was briefly used again for a few weeks of theParis Commune,in May 1871.

Overview and origins[edit]

Precursor[edit]

The prominent atheist essayist and philosopherSylvain Maréchalpublished the first edition of hisAlmanach des Honnêtes-gens(Almanac of Honest People) in 1788.[2]The first month in the almanac is "Mars, ou Princeps" (March, or First), the last month is "Février, ou Duodécembre" (February, or Twelfth). The lengths of the months are the same as those in the Gregorian calendar; however, the 10th, 20th, and 30th days are singled out of each month as the end of adécade(group of ten days). Individual days were assigned, instead of to the traditional saints, to people noteworthy for mostly secular achievements. Later editions of the almanac would switch to the Republican Calendar.[3]

History[edit]

The days of theFrench RevolutionandRepublicsaw many efforts to sweep away various trappings of theAncien Régime(the old feudal monarchy); some of these were more successful than others. The new Republican government sought to institute, among other reforms, a new social and legal system, a new system of weights and measures (which became themetric system), and a new calendar. Amid nostalgia for the ancientRoman Republic,the theories of theAge of Enlightenmentwere at their peak, and the devisers of the new systems looked to nature for their inspiration. Natural constants, multiples of ten, andLatinas well asAncient Greekderivations formed the fundamental blocks from which the new systems were built.

The new calendar was created by a commission under the direction of the politicianGilbert Rommeseconded byClaude Joseph FerryandCharles-François Dupuis.They associated with their work the chemistLouis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau,the mathematician and astronomerJoseph-Louis Lagrange,the astronomerJérôme Lalande,the mathematicianGaspard Monge,the astronomer and naval geographerAlexandre Guy Pingré,and the poet, actor and playwrightFabre d'Églantine,who invented the names of the months, with the help ofAndré Thouin,gardener at theJardin des plantesof theMuséum National d'Histoire Naturellein Paris. As therapporteurof the commission, Charles-Gilbert Romme presented the new calendar to theJacobin-controlledNational Conventionon 23 September 1793, which adopted it on 24 October 1793 and also extended itprolepticallyto itsepochof 22 September 1792. It is because of his position as rapporteur of the commission that the creation of the republican calendar is attributed to Romme.[4]

The calendar is frequently named the "French Revolutionary Calendar" because it was created during the Revolution, but this is a slight misnomer. In France, it is known as thecalendrier républicainas well as thecalendrier révolutionnaire.There was initially a debate as to whether the calendar should celebrate the Great Revolution, which began in July 1789, or the Republic, which was established in 1792.[5]Immediately following 14 July 1789, papers and pamphlets started calling 1789 year I of Liberty and the following years II and III. It was in 1792, with the practical problem of dating financial transactions, that the legislative assembly was confronted with the problem of the calendar. Originally, the choice of epoch was either 1 January 1789 or 14 July 1789. After some hesitation the assembly decided on 2 January 1792 that all official documents would use the "era of Liberty" and that the year IV of Liberty started on 1 January 1792. This usage was modified on 22 September 1792 when the Republic was proclaimed and the Convention decided that all public documents would be dated Year I of the French Republic. The decree of 2 January 1793 stipulated that the year II of the Republic began on 1 January 1793; this was revoked with the introduction of the new calendar, which set 22 September 1793 as the beginning of year II. The establishment of the Republic was used as the epochal date for the calendar; therefore, the calendar commemorates the Republic, and not the Revolution.

French coins of the period naturally used this calendar. Many show the year (French:an) in Arabic numbers, although Roman numerals were used on some issues. Year 11 coins typically have a XI date to avoid confusion with the Roman II.

The French Revolution is usually considered to have ended with thecoup of 18 Brumaire,Year VIII (9 November 1799), thecoup d'étatofNapoleon Bonaparteagainst the established constitutional regime of theDirectoire.

TheConcordat of 1801re-established the Roman Catholic Church as an official institution in France, although not as the state religion of France. The concordat took effect from Easter Sunday, 28 Germinal, Year XI (8 April 1802); it restored the names of the days of the week to the ones from theGregorian calendar,and fixed Sunday as the official day of rest and religious celebration.[6]However, the other attributes of the republican calendar, the months, and years, remained as they were.

The French Republic ended with thecoronation of NapoleonasEmpereur des Français(Emperor of the French) on 11 Frimaire, Year XIII (2 December 1804), but the republican calendar would remain in place for another year.Napoleonfinally abolished the republican calendar with effect from 1 January 1806 (the day after 10 Nivôse Year XIV), a little over twelve years after its introduction. It was, however, used again briefly in theJournal officielfor some dates during a short period of theParis Commune,6–23 May 1871 (16 Floréal–3 Prairial Year LXXIX).[7]

Calendar design[edit]

Years appear in writing asRoman numerals(usually), with epoch 22 September 1792, the beginning of the "Republican Era" (the day theFrench First Republicwas proclaimed, one day after the Convention abolished the monarchy). As a result, Roman Numeral I indicates the first year of the republic, that is, the year before the calendar actually came into use. By law, the beginning of each year was set at midnight, beginning on the day the apparentautumnal equinoxfalls at the Paris Observatory.

There were twelve months, each divided into three ten-day weeks calleddécades.The tenth day,décadi,replaced Sunday as the day of rest and festivity. The five or six extra days needed to approximate the solar ortropical yearwere placed after the final month of each year and calledcomplementary days.This arrangement was an almost exact copy of thecalendar used by the Ancient Egyptians,though in their case the year did not begin and end on the autumnal equinox.

A period of four years ending on a leap day was to be called a "Franciade". The name "Olympique"was originally proposed[8]but changed to Franciade to commemorate the fact that it had taken the revolution four years to establish a republican government in France.[9]

The leap year was calledSextile,an allusion to the "bissextile"leap yearsof the Julian and Gregorian calendars, because it contained a sixth complementary day.

Decimal time[edit]

Each day in the Republican Calendar was divided into ten hours, each hour into 100 decimal minutes, and each decimal minute into 100 decimal seconds. Thus an hour was 144 conventional minutes (2.4 times as long as a conventional hour), a minute was 86.4 conventional seconds (44% longer than a conventional minute), and a second was 0.864 conventional seconds (13.6% shorter than a conventional second).

Clockswere manufactured to display thisdecimal time,but it did not catch on. Mandatory use of decimal time was officially suspended 7 April 1795, although some cities continued to use decimal time as late as 1801.[10]

The numbering of years in the Republican Calendar byRoman numeralsran counter to this general decimalization tendency.

Months[edit]

The Republican calendar year began the day theautumnal equinoxoccurred in Paris, and had twelve months of 30 days each, which were given new names based on nature, principally having to do with the prevailing weather in and around Paris and sometimes evoking the MedievalLabours of the Months.The extra five or six days in the year were not given a month designation, but consideredSansculottidesorComplementary Days.

- Autumn:

- Vendémiaire(from Frenchvendange,which means grape harvest, derived from Latinvindemia'vintage'), starting 22, 23, or 24 September

- Brumaire(from Frenchbrume'mist', from Latinbrūma'winter solstice; winter; winter cold'), starting 22, 23, or 24 October

- Frimaire(from Frenchfrimas'frost'), starting 21, 22, or 23 November

- Winter:

- Spring:

- Summer:

- Messidor(from Latinmessis'harvest'), starting 19 or 20 June

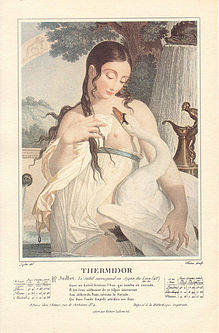

- Thermidor(from Greekthermon'summer heat'), starting 19 or 20 July; on many printed calendars of Year II (1793–94), the month ofThermidorwas namedFervidor(from Latinfervidus,"burning hot" )

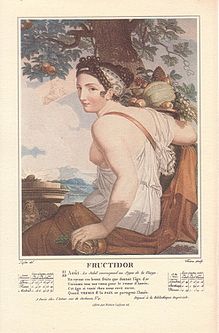

- Fructidor(from Latinfructus'fruit'), starting 18 or 19 August

Most of the month names were new words coined from French,Latin,orGreek.The endings of the names are grouped by season.Dormeans 'giving' in Greek.[11]

In Britain, a contemporary wit mocked the Republican Calendar by calling the months:Wheezy,Sneezy,andFreezy;Slippy,Drippy,andNippy;Showery,Flowery,andBowery;Hoppy,Croppy,andPoppy.[12][13]The historianThomas Carlylesuggested somewhat more serious English names in his 1837 workThe French Revolution: A History,[11]namely Vintagearious, Fogarious, Frostarious, Snowous, Rainous, Windous, Buddal, Floweral, Meadowal, Reapidor, Heatidor, and Fruitidor. Like the French originals, they areneologismssuggesting a meaning related to the season.

Ten days of the week[edit]

The month is divided into threedécadesor "weeks" of ten days each, named simply:

- primidi(first day)

- duodi(second day)

- tridi(third day)

- quartidi(fourth day)

- quintidi(fifth day)

- sextidi(sixth day)

- septidi(seventh day)

- octidi(eighth day)

- nonidi(ninth day)

- décadi(tenth day)

Décadis became official days of rest instead of Sundays, in order to diminish the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. They were used for the festivals of a succession of new religions meant to replace Catholicism: theCult of Reason,theCult of the Supreme Being,theDecadary Cult,andTheophilanthropy.Christian holidays were officially abolished in favor of revolutionary holidays.

The law of 13 Fructidor year VI (August 30, 1798) required that marriages must only be celebrated on décadis. This law was applied from the 1st Vendémiaire year VII (September 22, 1798) to 28 Pluviôse year VIII (February 17, 1800).

Décades were abandoned at the changeover from Germinal to Floréal an X (20 to 21 April 1802), after Napoleon's Concordat with the Pope.[14]

Rural calendar[edit]

TheRoman Catholic Churchused acalendar of saints,which named each day of the year after an associatedsaint.To reduce the influence of the Church,Fabre d'Églantineintroduced a Rural Calendar in which each day of the year had a unique name associated with therural economy,stated to correspond to the time of year. Everydécadi(ending in 0) was named after an agricultural tool. Eachquintidi(ending in 5) was named for a common animal. The rest of the days were named for "grain, pasture, trees, roots, flowers, fruits" and other plants, except for the first month of winter, Nivôse, during which the rest of the days were named after minerals.[15][16]

Our starting point was the idea of celebrating, through the calendar, the agricultural system, and of leading the nation back to it, marking the times and the fractions of the year by intelligible or visible signs taken from agriculture and the rural economy. (...)

As the calendar is something that we use so often, we must take advantage of this frequency of use to put elementary notions of agriculture before the people – to show the richness of nature, to make them love the fields, and to methodically show them the order of the influences of the heavens and of the products of the earth.

The priests assigned the commemoration of a so-called saint to each day of the year: this catalogue exhibited neither utility nor method; it was a collection of lies, of deceit or of charlatanism.

We thought that the nation, after having kicked out this canonised mob from its calendar, must replace it with the objects that make up the true riches of the nation, worthy objects not from a cult, but from agriculture – useful products of the soil, the tools that we use to cultivate it, and the domesticated animals, our faithful servants in these works; animals much more precious, without doubt, to the eye of reason, than the beatified skeletons pulled from the catacombs of Rome.

So we have arranged in the column of each month, the names of the real treasures of the rural economy. The grains, the pastures, the trees, the roots, the flowers, the fruits, the plants are arranged in the calendar, in such a way that the place and the day of the month that each product occupies is precisely the season and the day that Nature presents it to us.

— Fabre d'Églantine, "Rapport fait à la Convention nationale au nom de la Commission chargée de la confection du Calendrier",[17]Imprimerie nationale, 1793

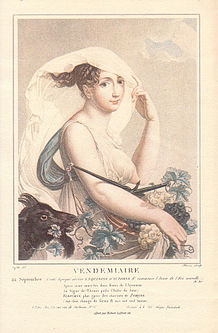

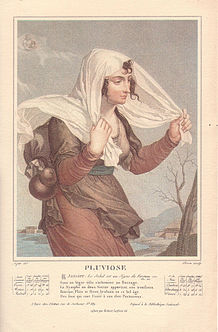

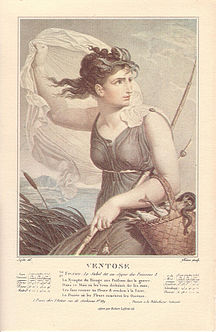

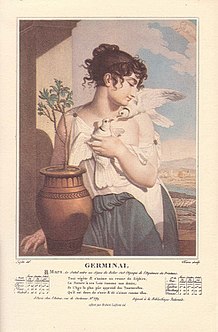

The following pictures, showing twelve allegories for the months, were illustrated by French painterLouis Lafitte(1779–1828), and engraved bySalvatore Tresca(1750–1815).[18]

Autumn[edit]

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Winter[edit]

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Spring[edit]

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Summer[edit]

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Complementary days[edit]

Five extra days – six inleap years– were national holidays at the end of every year. These were originally known asles sans-culottides(aftersans-culottes), but after year III (1795) asles jours complémentaires:

- 1st complementary day:La Fête de la Vertu,"Celebration of Virtue", on 17 or 18 September

- 2nd complementary day:La Fête du Génie,"Celebration of Talent", on 18 or 19 September

- 3rd complementary day:La Fête du Travail,"Celebration of Labour", on 19 or 20 September

- 4th complementary day:La Fête de l'Opinion,"Celebration of Convictions", on 20 or 21 September

- 5th complementary day:La Fête des Récompenses,"Celebration of Honors (Awards)", on 21 or 22 September

- 6th complementary day:La Fête de la Révolution,"Celebration of the Revolution", on 22 or 23 September (on leap years only)

Converting from the Gregorian Calendar[edit]

During the Republic[edit]

Below are the Gregorian dates each year of the Republican Era (Ère Républicainein French) began while the calendar was in effect.

| ER | AD/CE |

|---|---|

| I (1) | 22 September 1792 |

| II (2) | 22 September 1793 |

| III (3) | 22 September 1794 |

| IV (4) | 23 September 1795* |

| V (5) | 22 September 1796 |

| VI (6) | 22 September 1797 |

| VII (7) | 22 September 1798 |

| VIII (8) | 23 September 1799* |

| IX (9) | 23 September 1800 |

| X (10) | 23 September 1801 |

| XI (11) | 23 September 1802 |

| XII (12) | 24 September 1803* |

| XIII (13) | 23 September 1804 |

| XIV (14) | 23 September 1805 |

| LXXIX (79) | 23 September 1870 |

Leap years are highlighted

- Extra (sextile) day inserted before date, due to previous leap year[19]

After the Republic[edit]

The Republican Calendar was abolished in the year XIV (1805). After this year, there are two historically attested calendars which may be used to determine dates. Both calendars gave the same dates for years 17 to 52 (1808–1844), always beginning on 23 September, and it was suggested, but never adopted, that the reformed calendar be implemented during this period, before the Republican Calendar was abolished.

- Republican Calendar:The only legal calendar during the Republic. The first day of the year, 1 Vendémiaire, is always the day the autumn equinox occurs in Paris. About every 30 years, leap years are 5 years apart instead of 4, as happened between the leap years 15 and 20.[20]The lengths of the first 524 years were calculated by Delambre.

- Reformed Republican Calendar:Following a proposal by Delambre in order to make leap years regular and predictable, with leap years being every year divisible by 4, except years divisible by 100 and not by 400. Years divisible by 4000 would also be ordinary years. Intended to be implemented in year 3, the reformed calendar was abandoned after the death of the head of the calendar committee, Gilbert Romme. This calendar also has the benefit that every year in the third century of the Republican Era (1992–2091) begins on 22 September.[21]

| ER | AD/CE | Republican | Reformed |

|---|---|---|---|

|

XV (15) |

1806 |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XVI (16) |

1807 |

24 September* |

23 September |

|

XVII (17) |

1808 |

23 September |

23 September* |

|

XVIII (18) |

1809 |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XIX (19) |

1810 |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XX (20) |

1811 |

23 September |

23 September |

|

CCXXIX (229) |

2020 |

22 September |

22 September* |

|

CCXXX (230) |

2021 |

22 September |

22 September |

|

CCXXXI (231) |

2022 |

23 September* |

22 September |

|

CCXXXII (232) |

2023 |

23 September |

22 September |

|

CCXXXIII (233) |

2024 |

22 September |

22 September* |

|

CCXXXIV (234) |

2025 |

22 September |

22 September |

|

CCXXXV (235) |

2026 |

23 September* |

22 September |

|

CCXXXVI (236) |

2027 |

23 September |

22 September |

|

CCXXXVII (237) |

2028 |

22 September |

22 September* |

|

CCXXXVIII (238) |

2029 |

22 September |

22 September |

|

CCXXXIX (239) |

2030 |

22 September |

22 September |

|

CCXL (240) |

2031 |

23 September* |

22 September |

|

CCXLI (241) |

2032 |

22 September |

22 September* |

Leap years are highlighted

- Extra (sextile) day inserted before date, due to previous leap year

Current date and time[edit]

For this calendar, Delambre's revised method of calculating leap years is used. Other methods may differ by one day. Time may be cached and therefore not accurate. Decimal time is according to Paris mean time, which is 9 minutes 21 seconds (6.49 decimal minutes) ahead of Greenwich Mean Time. (This toolcalibrates the time, if calibration is desired.)

| 232 | Messidor | CCXXXII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Criticism and shortcomings[edit]

Leap yearsin the calendar are a point of great dispute, due to the contradicting statements in the establishing decree[22]stating:

Each year begins at midnight, with the day on which the true autumnal equinox falls for theParis Observatory.

and:

The four-year period, after which the addition of a day is usually necessary, is called theFranciadein memory of the revolution which, after four years of effort, led France to republican government. The fourth year of theFranciadeis calledSextile.

These two specifications are incompatible, as leap years defined by the autumnal equinox in Paris do not recur on a regular four-year schedule. It was erroneously believed that one leap day would be skipped automatically every 129 years,[23]on average, but actually five years would sometimes pass between leap years, about three times per century. Thus, the years III, VII, and XI were observed as leap years, and the years XV and XX were also planned as such, even though they were five years apart.

A fixed arithmetic rule for determining leap years was proposed byJean Baptiste Joseph Delambreand presented to the Committee of Public Education byGilbert Rommeon 19 Floréal An III (8 May 1795). The proposed rule was to determine leap years by applying the rules of the Gregorian calendar to the years of the French Republic (years IV, VIII, XII, etc. were to be leap years) except that year 4000 (the last year of ten 400-year periods) should be a common year instead of a leap year. Shortly thereafter, Romme was sentenced to the guillotine and committed suicide, and the proposal was never adopted, althoughJérôme Lalanderepeatedly proposed it for a number of years. The proposal was intended to avoid uncertain future leap years caused by the inaccurate astronomical knowledge of the 1790s (even today, this statement is still valid due to the uncertainty inΔT). In particular, the committee noted that the autumnal equinox of year 144 was predicted to occur at 11:59:40 pmlocal apparent timein Paris, which was closer to midnight than its inherent 3 to 4 minute uncertainty.

The calendar was abolished by an act dated 22 Fructidor an XIII (9 September 1805) and signed byNapoleon,which referred to a report byMichel-Louis-Étienne Regnaud de Saint-Jean d'AngélyandJean Joseph Mounier,listing two fundamental flaws.

- The rule for leap years depended upon the uneven course of the sun, rather than fixed intervals, so that one must consult astronomers to determine when each year started, especially when the equinox happened close to midnight, as the exact moment could not be predicted with certainty.

- Both the era and the beginning of the year were chosen to commemorate a historical event that occurred on the first day of autumn in France, whereas the other European nations began the year near the beginning of winter or spring, thus being impediments to the calendar's adoption in Europe and America, and even a part of the French nation, where the Gregorian calendar continued to be used, as it was required for religious purposes.

The report also noted that the 10-day décade was unpopular and had already been suppressed three years earlier in favor of the seven-day week, removing what was considered by some as one of the calendar's main benefits.[24]The 10-day décade was unpopular with laborers because they received only one full day of rest out of ten, instead of one in seven, although they also got a half-day off on the fifth day (thus 36 full days and 36 half days in a year, for a total of 54 free days, compared to the usual 52 or 53 Sundays). It also, by design, conflicted with Sunday religious observances.

Another criticism of the calendar was that despite the poetic names of its months, they were tied to the climate and agriculture ofmetropolitan Franceand therefore not applicable toFrance's overseas territories.[25]

Famous dates and other cultural references[edit]

This sectionpossibly containsoriginal research.(October 2017) |

The "Coup of 18 Brumaire"or" Brumaire "was thecoup d'étatofNapoleon Bonaparteon 18 Brumaire An VIII (9 November 1799), which many historians consider to be the end of the French Revolution.Karl Marx's 1852 essayThe Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonapartecomparesthe coup d'état of 1851ofLouis Napoléonunfavorably to his uncle's earlier coup, with the statement "History repeats... first as tragedy, then as farce".

Another famous revolutionary date is9 Thermidor An II(27 July 1794), the date the Convention turned againstMaximilien Robespierre,who, along with others associated withthe Mountain,wasguillotinedthe following day. Based on this event, the term "Thermidorian" entered theMarxistvocabulary as referring to revolutionaries who destroy the revolution from the inside and turn against its true aims. For example,Leon Trotskyand his followers used this term aboutJoseph Stalin.

Émile Zola's novelGerminaltakes its name from the calendar's month of Germinal.

The seafood dishLobster Thermidorwas named after the 1891 playThermidor,set during the Revolution.[26][27]

The French frigates of theFloréalclassall bear names of Republican months.

A decree of theNational Conventionon 9 Brumaire An III, 30 October 1794, established theÉcole normale supérieure.The date appears prominently above the main door of the school.

The French composerFromental Halévywas born 7 Prairial VIII (27 May 1799), the day offromental(oatgrass).

Neil Gaiman'sThe Sandmanseries included a story called "Thermidor" that takes place in that month during the French Revolution.[28]

See also[edit]

- Agricultural cycle

- Calendar reform

- Dechristianisation of France

- Decimal time

- Soviet calendar

- Solar Hijri calendar,astronomical equinox-based calendar used in Iran

- World Calendar

References[edit]

- ^"The 12 Months of the French Republican Calendar | Britannica".britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 19 May 2023.Retrieved24 May2023.

- ^Sylvain, Maréchal (1836).Almanach des Honnêtes-gens.Gallica. pp. 14–15.Archivedfrom the original on 3 September 2015.Retrieved3 June2014– via gallica.bnf.fr.

- ^Sylvain, Maréchal (1799)."Almanach des honnêtes gens pour l'an VIII".gallica.bnf.fr.Gallica.Archivedfrom the original on 25 May 2020.Retrieved19 November2019.

- ^James Guillaume,Procès-verbaux du Comité d'instruction publique de la Convention nationale,t. I, pp. 227–228 et t. II, pp. 440–448; Michel Froechlé, "Le calendrier républicain correspondait-il à une nécessité scientifique?", Congrès national des sociétés savantes: scientifiques et sociétés, Paris, 1989, pp. 453–465.

- ^Le calendrier républicain: de sa création à sa disparition.Bureau des longitudes. 1994. p. 19.ISBN978-2-910015-09-1.

- ^"Concordat de 1801 Napoleon Bonaparte religion en france Concordat de 1801".Roi-president. 21 November 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 10 September 2012.Retrieved30 January2009.

- ^Réimpression du Journal Officiel de la République française sous la Commune du 19 mars au 24 mai 1871.V. Bunel. 1871. pp. 477–.Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2024.Retrieved26 December2018.

- ^Le calendrier républicain: de sa création à sa disparition.Bureau des longitudes. 1994. p. 26.ISBN978-2-910015-09-1.

- ^Le calendrier républicain: de sa création à sa disparition.Bureau des longitudes. 1994. p. 36.ISBN978-2-910015-09-1.

- ^Richard A. Carrigan, Jr. "Decimal Time".American Scientist,(May–June 1978),66(3):305–313.

- ^abThomas Carlyle (1867).The French revolution: a history.Harper.Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2024.Retrieved3 November2021.

- ^Sporting Magazine,vol. 15, Rogerson and Tuxford, January 1800, p. 210,archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2023,retrieved23 December2014

- ^John Brady (1812),Clavis Calendaria: Or, A Compendious Analysis of the Calendar; Illustrated with Ecclesiastical, Historical, and Classical Anecdotes,vol. 1, Rogerson and Tuxford, p. 38,archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2024,retrieved10 October2018

- ^Antoine Augustin Renouard (1822).Manuel pour la concordance des calendriers républicain et grégorien(2 ed.). A. A. Renouard.Retrieved14 September2009.

- ^Edouard Terwecoren(1870).Collection de Précis historiques.J. Vandereydt. p. 31.

- ^Philippe-Joseph-Benjamin Buchez, Prosper Charles Roux (1837).Histoire parlementaire de la révolution française.Paulin. p. 415.

- ^Convention nationale. Rapport fait à la Convention nationale, dans la séance du 3 du second mois de la seconde année de la République Française, au nom de la Commission chargée de la confection du Calendrier; Par Ph. Fr. Na. Fabre-D'Eglantine,... Imprimé par ordre de la Convention nationaleavailable atGallica

- ^"Vendémiaire".Paris Musées. Les collections.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2023.Retrieved3 April2023.

- ^Parise, Frank (2002).The Book of Calendars.Gorgias Press. p. 376.ISBN978-1-931956-76-5.

- ^Sébastien Louis Rosaz (1810).Concordance de l'Annuaire de la République française avec le calendrier grégorien.

- ^"Brumaire – Calendrier Républicain".Prairial.free.fr. Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2011.Retrieved30 January2009.

- ^"Le Calendrier Republicain".Gefrance. 30 May 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 24 June 2021.Retrieved25 June2021.

- ^"Instruction sur l'ère de la République, à la suite du décret du 3 brumaire, an II"(PDF).Université de Toulouse.Archived(PDF)from the original on 16 December 2023.Retrieved27 November2023.

- ^Antoine Augustin Renouard (1822).Manuel pour la concordance des calendriers républicain et grégorien: ou, Recueil complet de tous les annuaires depuis la première année républicaine(2 ed.). A. A. Renouard. p. 217.

- ^Canes, Kermit (2012).The Esoteric Codex: Obsolete Calendars.LULU Press.ISBN978-1-365-06556-9.

- ^James, Kenneth (15 November 2006).Escoffier: The King of Chefs.Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 44.ISBN978-1-85285-526-0.Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2024.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^"Lobster thermidor".Online Dictionary.Merriam-Webster.Archivedfrom the original on 20 June 2016.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^Gaiman, Neil(w),Woch, Stan(p),Giordano, Nick(i),Vozzo, Daniel(col),Klein, Todd(let),Berger, Karen(ed). "Thermidor"The Sandman,vol. 29 (August 1991).Vertigo Comics.

Further reading[edit]

- Ozouf, Mona, 'Revolutionary Calendar' in Furet, François and Mona Ozouf, eds.,Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution(1989)

- Shaw, Matthew,Time and the French Revolution: a history of the French Republican Calendar, 1789-Year XIV(2011)