Frisian freedom

| Frisian freedom Fryske frijheid | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de factoautonomous regionof theHoly Roman Empire | |||||||||

| c. 1100–1498 | |||||||||

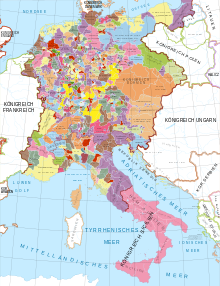

Map of Frisia in 1300 | |||||||||

| Demonym | Frisian | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• AllegedKarelsprivilege | c. 800 | ||||||||

• Earliest evidence of regionalautonomy | c. 1100 | ||||||||

• Recognition of imperial liberty bySigismund | 1417 | ||||||||

• Establishment of theCounty of East Frisia | 1464 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1498 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

TheFrisian freedom(West Frisian:Fryske frijheid;Dutch:Friese vrijheid;German:Friesische Freiheit) was a period of the absence offeudalisminFrisiaduring theMiddle Ages.Its main aspects included freedom fromserfdom,feudal dutiesandtaxation,as well as theelectionofjudgesandadjudicators.

According to medieval chronicles, exemption from feudalism was granted to the Frisians byCharlemagne,although the earliest clear evidence of the Frisian freedom has been dated to the 13th century. Throughout the Middle Ages, Frisians resisted the expansion of feudalism into their lands, fighting aseries of warsagainst theCounty of Hollandin order to maintain theirautonomy.During this period, Frisian society was organised in a network ofrural communes,people largely governed themselves throughpublic assemblies,and elected judges established a codified legal system without any kind ofcentral government.Frisians formed treaties with other powers to protect their freedom, which was recognised by a number of German kings during theLate Middle Ages.

Frisian freedom was brought to an end in the late-15th century, as increasing levels ofclass stratificationin the East culminated in the establishment of theCounty of East Frisia,while West Frisia was brought under the rule ofSaxony.Since the 16th century, the Frisian freedom has been subject to numerous reinterpretations. During theDutch Revolt,it was used to argue for the restoration of rights lost underHabsburg rule,and Frisian freedom later inspiredAmericanandFrench Revolutionaries.One Frisian history book from this period contained a fictionalised portrayal of the Frisian freedom, which deeply influenced later Frisian historiography. It was later recast as anational mythbyFrisian nationalism,which depicted freedom as an inherent trait of the Frisian people and portrayed a level of historical continuity that is disputed by historians.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The region ofFrisiaextends along theNorth Sea coastline,from theZuiderzeein the west to theWeserin the east. In most ofwestern Europeduring theHigh Middle Ages,social organisation developed along the lines offeudalism,as nobles gained the right ofsovereigntyover certain territories; but Frisia notably developed along a different path.[1]Beginning in the mid-11th century,Medieval communesspread fromnorthern Italyacross much of Europe, gathering strength in areas outside the authority of feudal lords. These communes extendedpersonal freedomsincludingpublic participationto its populace, which cultivated within them an antagonism towards feudalism.[2]Within theHoly Roman Empire,some of these communes, including in Frisia, eliminated the power of local princes, establishing quasi-republicansystems of government.[3]

Development of autonomy

[edit]

Frisian lands existed in a state ofautonomyfrom at least the 11th century.[4]Although Frisia was officially brought under the rule of the Holy Roman Empire, ade factosystem ofself-governancedeveloped in the region.[5]The Frisians disregarded the rights of local feudal lords, but still recognised the rule of the Empire, although this remained at a distance in practice.[6]

The earliest references to a "Frisian freedom" date back to the 13th century;[7]with the first documentary evidence of self-governance being found inc. 1220,[1]while the encyclopedistBartholomaeus Anglicusreferred to Frisian attitudes towardslibertyinc. 1240.[8]Although medieval Frisia has been compared to theItalian city-statesandOld Swiss Confederacy,due to their shared quasi-republican systems of government, Frisia was unique in its contemporary understanding of liberty as an intrinsic value.[9]

For most of its history, Frisian self-governance was maintained inEast Frisia,between the Weser andLauwersrivers.[1]Meanwhile, parts ofWest Frisiaperiodically fell under the feudal occupation of theCounty of Holland.[10]During theFriso-Hollandic Wars,the concept of Frisian freedom was used to mobilise armed resistance to feudalisation attempts by the counts of Holland.[11]

Communal and legal institutions

[edit]In contrast to developments in feudalcounties,the Frisiannobilitynever developed feudal titles,knighthoodswere never established, and thecentralisationofpolitiesintostateswas a slow-moving process.Rural communesbecame the dominant institutional form in Frisia, with higher-level subdivisions coalescing into self-governing districts, known ascommunitates terrae(West Frisian:Steatsmienskippen;German:Landesgemeinden).[1]Frisians largely governed themselves through community assemblies,[10]also known asthings.[12]

Each year, Frisians electedjudgesfrom their own ranks.[13]Allfreeholderswere eligible to becomeadjudicatorsand were rotated out on an annual basis.[12]The Frisian historianUbbo Emmiuslater claimed that the election of judges was "the principle element of liberty".[14]Frisian freedom incentivised the codification ofcustomary law;the earliest surviving Frisian legal manuscripts date back to the late 13th century and the most recent date to the early 16th century.[15]

Medieval Frisian legal codes established a kind ofhonour system,in which compensation tariffs were used to preventfeuds.This was implemented without any kind ofcentral government,with historian Han Nijdam comparing its functioning to theIcelandic Commonwealth.[16]In 1323, the "Ubstalsboom Laws" were promulgated, declaring that "if any prince, secular or ecclesiastical, [...] shall have assailed us, Frisians, or any of us, wanting to subject us to the yoke of servitude, then together, through a joint call-up and by force of arms, we shall protect our liberty."[17]In 1361, the city ofGroningenattempted to revive the Upstalsboom League as its leading polity.[18]

Recognition

[edit]

It wasn't until theLate Middle Agesthat Frisian freedom was officially recognised by foreign feudal powers.[12]In 1232, thePrince-Bishopric of Utrechtrecognised that the Frisians "are free men, and released from any yoke of servitude or anyone’s oppressive rule."[17]The FrenchBartholomaeus Anglicusalso recognised the Frisians' freedom from feudal rule and serfdom, as well as their annual election of judges, writing that they "hazard their life for liberty and prefer death to being oppressed by the yoke of servitude".[19]

In the early 13th century, mentions of Frisian liberties having been granted byCharlemagnebegan to appear in historical literature.[20]According to these medieval chronicles, the Frisian freedom was established by Charlemagne, the firstHoly Roman Emperor.[21]But no evidence of this "Karelsprivilege"has been found prior to the 13th century, leading historian Han Nijdam to describe it as an" ideological embellishment ".[22]Frisian scholars also made frequent references to Roman law and philosophy, in their justifications for the Frisian freedom.[23]Between 1297 and 1319, in an attempt to retroactively justify their freedom from feudal rule, some Frisians fabricated a charter that they alleged had been written by Charlemagne and confirmed their freedom fromserfdom,feudal dutiesandtaxation.[24]

In 1248,William II of Hollandconfirmed "all the rights, liberties and privileges conceded to all Frisians by the emperor Charlemagne", but the terms were kept vague, so the decree had little significant effect.[25]In 1338, Frisiancommunitatessent a letter toPhilip VI of France,in which they request he be "mindful of the most beneficial gift of Frisian freedom, [...] conceded to us by Charlemagne, king of the Romans [...], in perpetuity."[26]That same year, following a dispute between Frisians and the city ofGroningen,arbitrators issued a charter that declared Groningen would agree to protect the Frisian freedom from feudal lords.[27]In 1361, another charter was issued by a league of Frisianterraeand the city of Groningen, which reaffirmed a joint pact to protect Frisian freedom from "coercion by oppression".[26]This alliance was later invoked during attempts by theBurgundian Stateto conquer Frisia.[14]

According to a Frisian law book fromc. 1295,Frisians collaborated withRudolf I of Germanyon military campaigns, in return for the protection of the Frisian freedom.[28]In 1417, the German kingSigismundissued a charter that granted Frisia "imperial liberty" from princely rule.[29]But as the terms of the charter required that they paytributeto the state, the Frisians rejected it. Instead, in 1421, they briefly recognised the count of Holland and the Empire subsequently declared Frisia to be a rebellious province.[30]In 1493, German kingMaximilian Iissued a charter that granted the West Frisians imperial privilege, but this too was rejected by the Frisians, as it stipulated the payment of tribute.[31]A chronicle at theAduard Abbeyalso recognised that the Frisians "utterly abhorred the state of servitude for reason of the severity of the princes, as they had experienced earlier."[17]

Dissolution

[edit]

A largely leaderless society, from 1298, references began to be made to urban officeholders known asaldermenand elected military leaders known ashaedlings,which were often compared to the Italianpodestàs.[32]By the mid-14th century,village heads(West Frisian:haedlingen) had grown more rich and powerful, developing into an agrarianaristocracyand becoming the region'sde factoruling class.[33]Between theEmsandJade riversin eastern Frisia, the strength of communal institutions were diminished and the communes effectively disappeared, while in the west, village heads increasingly exerted more influence over the communes.[34]As the power of thehaedlingengrew, elements of the Frisian freedom such aspersonal freedomand the election of judges were discarded, as freedom was recast to mean freedom from foreign princes.[19]

In 1420, theEast Frisian chieftainsOcko II tom BrokandSibet Papingaformed an alliance to protect the Frisian freedom from theTeutonic Order;they reinterpreted Frisian freedom in aspolitical freedomfrom foreign rule, rather than freedom from feudal servitude.[14]In 1430, mounting opposition to the East Frisian chieftains culminated with the establishment of a "Freedom League", in which an alliance of Frisian communities attempted to end their quasi-feudal rule.[14]In the mid-to-late 15th century, the Frisianhaedlingenrecast the Frisian freedom to simply mean freedom from external taxation.[19]In 1464, one of the most powerful East Frisian chieftains,Ulrich I,had reorganised the eastern territories into theCounty of East Frisia,ending the Frisian freedom there and finally establishing feudal rule in the east.[31]

The Frisian freedom finally came to an end as a result ofcivil warbetween theSchieringersandVetkopers,two factions of the Frisian nobility.[12]In 1498, Maximilian appointedAlbert III, Duke of Saxonyasgovernorof the region,[35]with the support of theSchieringers.[12]In 1504, Frisia was officially brought underSaxon law.[36]Although the Frisian freedom was abolished, the Saxons ultimately struggled to introduce feudalism in west Frisia, as the localhaedlingenrejected moves to bring them into the nobility.[31]In an attempt to capture Frisia from the Saxons, in 1514,Charles II, Duke of Gueldersinvaded Frisia, claiming his intention to restore the Frisian freedom.[37]

Modern reinterpretations

[edit]Early modern period

[edit]The concept of the Frisian freedom was reinterpreted during theDutch Revolt,when it was used to argue for the reinstatement of historic rights that had been lost underHabsburg rule.[38]In Friesland, the revolt was seen as a restoration of the Frisian freedom, as described in the writings of the Frisian republicanUbbo Emmius.[39]

Towards the end of the 16th century, a fictionalised version of thehistory of Frisia,Andreas Cornelius'sCroniicke ende waarachtige Beschrijvinge van Vrieslant,was published. Although its account of events was heavily mythologised, the book became very influential on the development of Frisian historiography over the subsequent centuries.[40]

The idea of the Frisian freedom continued to endure into the late 18th century;American RevolutionaryJohn Adamscommented that Frisians were "famous for the spirit of liberty", whileFrench RevolutionaryHonoré Gabriel Riqueticompared Frisian to "a robust oak, with the sap of liberty preserving its strength and its verdure."[41]

Late modern period

[edit]By the end of theearly modern period,when Friesland was integrated into theUnited Kingdom of the Netherlands,the concept was again reinterpreted during the rise ofFrisian nationalism;the Frisian freedom lost its political connotations and was reconceived as a cultural trait of the Frisian people.[42]To nationalists of the 19th and 20th centuries,libertywas an innate characteristic of the Frisian national identity.[43]The Frisian freedom then became anational myth,assuming a continuous history of Frisian independence that lasted for over eight centuries, and the concept was subjected to increasedcommodification.This reconception has been disputed by academic historians, who have pointed out that the national myth was retroactively constructed in the 19th century and have debated the historical continuity of the Frisian freedom.[44]

References

[edit]- ^abcdVries 2015,p. 231.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 238–239.

- ^Vries 2015,p. 239.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 3;Vries 2015,pp. 231, 239–240.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 9;Vries 2015,pp. 231, 239–240.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 239–240.

- ^Nijdam 2023,pp. 6, 57;Vries 2015,pp. 229–231.

- ^Vries 2015,p. 229.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 240–241.

- ^abNijdam 2023,p. 9;Vries 2015,p. 231.

- ^Jensma 2018,p. 156.

- ^abcdeNijdam 2023,p. 9.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 9;Vries 2015,pp. 237–238.

- ^abcdVries 2015,p. 237.

- ^Nijdam 2014,p. 6.

- ^Nijdam 2014,p. 11.

- ^abcVries 2015,p. 236.

- ^Vries 2015,p. 242.

- ^abcVries 2015,p. 238.

- ^Introini 2018,pp. 58–59;Nijdam 2023,p. 16;Vries 2015,pp. 232, 234.

- ^Introini 2018,pp. 58–59;Jensma 2018,p. 156;Nijdam 2023,p. 16;Vries 2015,pp. 232, 234.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 16.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 241–244.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 232, 236, 238.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 232–233.

- ^abVries 2015,pp. 234–235.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 234, 237.

- ^Vries 2015,p. 235.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 232, 240.

- ^Vries 2015,p. 232.

- ^abcVries 2015,p. 233.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 244–245.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 231–232, 240.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 231–232.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 9;Vries 2015,pp. 233, 247.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 17.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 242–243.

- ^Jensma 2018,p. 156;Vries 2015,pp. 235–236.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 235–236.

- ^Nijdam 2023,p. 35.

- ^Vries 2015,pp. 229–230.

- ^Jensma 2018,pp. 156–157.

- ^Jensma 2018,p. 157.

- ^Jensma 2018,pp. 161–162.

Bibliography

[edit]- Introini, Angela (2018).A commented translation of "Thet Freske Riim": the myth of Frisian liberty between theory and practice(PDF)(Thesis).University of Venice.

- Jensma, Goffe (2018)."Remystifying Frisia: The 'experience economy' along the Wadden Sea coast".In Egberts, Linde; Schroor, Meindert (eds.).Waddenland Outstanding: The History, Landscape and Cultural Heritage of the Wadden Sea Region.Amsterdam:Amsterdam University Press.pp. 151–167.doi:10.1515/9789048537884-011.

- Nijdam, Han (2014)."Indigenous or Universal? A Comparative Perspective on Medieval (Frisian) Compensation Law"(PDF).In Andersen, Per; Tamm, Ditlev; Vogt, Helle (eds.).How Nordic are the Nordic Medieval Laws.Danish Association of Lawyers and Economists.pp. 161–181.

- Nijdam, Han (2023)."Preface to the Edition and Translation of the Old Frisian Main Text".Frisian Land Law.Leiden:Brill Publishers.pp. 3–61.doi:10.1163/9789004526419_002.ISBN978-90-04-52641-9.

- Vries, Oebele (2015)."Frisonica libertas: Frisian freedom as an instance of medieval liberty".Journal of Medieval History.41(2): 229–248.doi:10.1080/03044181.2015.1034162.