Théodore Géricault

Théodore Géricault | |

|---|---|

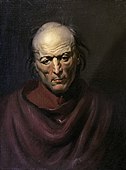

Théodore GéricaultbyHorace Vernet,c. 1822–1823 | |

| Born | Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault 26 September 1791 |

| Died | 26 January 1824(aged 32) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting,lithography |

| Notable work | The Raft of the Medusa |

| Movement | Romanticism |

Jean-Louis André Théodore Géricault(French:[ʒɑ̃lwiɑ̃dʁeteɔdɔʁʒeʁiko];26 September 1791 – 26 January 1824) was a Frenchpainterandlithographer,whose best-known painting isThe Raft of the Medusa.Despite his short life, he was one of the pioneers of theRomantic movement.

Early life[edit]

Born inRouen,France, Géricault moved to Paris with his family probably in 1797, where Théodore's father obtained employment in the family tobacco business based at theHôtel de Longuevilleon thePlace du Carrousel.Géricault's abilities were likely first recognized by the painter and art dealerJean-Louis Laneuville.Laneuville lived at the Hotel de Longueville alongside Jean-Baptiste Caruel, Théodore Géricault's maternal uncle, and other members of the extended Géricault family.[1]In 1808, Géricault began training at the studio of Carle Vernet, where he was educated in the tradition of English sporting art byCarle Vernet.In 1810, Géricault began studying classical figure composition underPierre-Narcisse Guérin,a rigorous classicist who disapproved of his student's impulsive temperament while recognizing his talent.[2]Géricault soon left the classroom, choosing to study at theLouvre,where from 1810 to 1815 he copied paintings byRubens,Titian,VelázquezandRembrandt.

During this period at the Louvre he discovered a vitality he found lacking in the prevailing school ofNeoclassicism.[2]Much of his time was spent inVersailles,where he found the stables of the palace open to him, and where he gained his knowledge of theanatomyand action of horses.[3]

Success[edit]

Géricault's first major work,The Charging Chasseur,exhibited at theParis Salonof 1812, revealed the influence of the style of Rubens and an interest in the depiction of contemporary subject matter. This youthful success, ambitious and monumental, was followed by a change in direction: for the next several years Géricault produced a series of small studies of horses and cavalrymen.[4]

He exhibitedWounded Cuirassierat the Salon in 1814, a work more labored and less well received.[4]Géricault in a fit of disappointment entered the army and served for a time in the garrison of Versailles.[3]In the nearly two years that followed the 1814 Salon, he also underwent a self-imposed study of figure construction and composition, all the while evidencing a personal predilection for drama and expressive force.[5]

A trip toFlorence,Rome, and Naples (1816–17), prompted in part by the desire to flee from a romantic entanglement with his aunt,[6]ignited a fascination withMichelangelo.Rome itself inspired the preparation of a monumental canvas, theRace of the Barberi Horses,a work of epic composition and abstracted theme that promised to be "entirely without parallel in its time".[7]However, Géricault never completed the painting and returned to France.

The Raft of the Medusa[edit]

Géricault continually returned to the military themes of his early paintings, and the series oflithographshe undertook on military subjects after his return from Italy are considered some of the earliest masterworks in that medium. Perhaps his most significant, and certainly most ambitious work, isThe Raft of the Medusa(1818–19), which depicted the aftermath of a contemporary French shipwreck,Méduse,in which the captain had left the crew and passengers to die.

The incident became a national scandal, and Géricault's dramatic interpretation presented a contemporary tragedy on a monumental scale. The painting's notoriety stemmed from its indictment of a corrupt establishment, but it also dramatized a more eternal theme, that of man's struggle with nature.[8]It surely excited the imagination of the youngEugène Delacroix,who posed for one of the dying figures.[9]

The classical depiction of the figures and structure of the composition stand in contrast to the turbulence of the subject, so that the painting constitutes an important bridge betweenneo-classicismandromanticism.It fuses many influences: theLast JudgmentofMichelangelo,the monumental approach to contemporary events byAntoine-Jean Gros,figure groupings byHenry Fuseli,and possibly the paintingWatson and the SharkbyJohn Singleton Copley.[10]

The painting ignited political controversy when first exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1819; it then traveled to England in 1820, accompanied by Géricault himself, where it received much praise.

While in London, Géricault witnessed urban poverty, made drawings of his impressions, and published lithographs based on these observations which were free of sentimentality.[11]He associated much there withCharlet,the lithographer and caricaturist.[3]In 1821, while still in England, he paintedThe Derby of Epsom.

Later life[edit]

After his return to France in 1821, Géricault was inspired to paint a series of ten portraits of the insane. These were the patients of a friend, Dr.Étienne-Jean Georget(a pioneer inpsychiatric medicine), with each subject exhibiting a different affliction.[12]There are five remaining portraits from the series, includingInsane Woman.

The paintings are noteworthy for their bravura style, expressive realism, and for their documenting of the psychological discomfort of individuals, made all the more poignant by the history of insanity in Géricault's family, as well as the artist's own fragile mental health.[13]His observations of the human subject were not confined to the living, for some remarkablestill-lifes—painted studies of severed heads and limbs—have also been ascribed to the artist.[14]

Géricault's last efforts were directed toward preliminary studies for several epic compositions, including theOpening of the Doors of the Spanish Inquisitionand theAfrican Slave Trade.[15]The preparatory drawings suggest works of great ambition, but Géricault's waning health intervened. Weakened by riding accidents and chronictubercularinfection, Géricault died in Paris in 1824 after a long period of suffering. His bronze figure reclines, brush in hand, on his tomb atPère Lachaise Cemeteryin Paris, above a low-relief panel ofThe Raft of the Medusa.

Works[edit]

-

Bust of a Black Man,1808 (Ajuda National Palace)

-

Wounded Cuirassier Leaving the Field of Battle,1814

-

Horse Head,1815

-

Riderless Racers in Rome,1817 (The Walters Art Museum[16])

-

The Capture of a Wild Horse,1817

-

Portrait ofLaure Bro,1818

-

Portrait of a young man1818

-

Heroic Landscape with Fishermen,1818

-

Portrait Study of a Youth,c. 1818–1820

-

Horse in the Storm,1820–1821

-

TheDerby of Epsom,1821

-

White Arabian Horse,before 1824

-

Nude,Musée Bonnat(Bayonne)

Les Monomanes(Portraits of the Insane)[17][edit]

-

Portrait of a Kleptomaniac(French:Portrait d'un CleptomaneakaLe Monomane du Vol), 1822 (Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent)

-

Man Suffering from Delusions of Military Rank(French:Le Monomane du Commandement Militaire), 1822 (CollectionOskar Reinhartam Römerholz,Winterthur)

-

Portrait of a Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy(French:La Monomane de l'envie), 1822 (Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon)

-

Portrait of a Child SnatcherakaThe Child ThiefakaThe Madman-Kidnapper(French:Le Monomane du vol d'enfants), 1822–1823 (Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts,Springfield, Massachusetts)

See also[edit]

- Joseph (art model),remembered for his professional relationship with Géricault

References[edit]

- ^"Titon Laneuville – Hôtel de Longueville".Gericaultlife.Retrieved28 October2023.

- ^abSee (Eitner 1987), p. 1.

- ^abcOne or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Gilman, D. C.;Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1906)..New International Encyclopedia(1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^abSee (Eitner 1987), p. 2.

- ^See (Eitner 1987), p. 3.

- ^Lüthy, Hans:The Temperament of Gericault,Theodore Gericault,p. 7. Salander-O'Reilly, 1987. In 1818 Alexandrine-Modeste Caruel gave birth to his son (christened Georges-Hippolyte and given into the care of the family doctor who then sent the child to Normandy where he was raised in obscurity). See alsoWheelock Whitney,Géricault in Italy,New Haven/London 1997, and Marc Fehlmann,Das Zürcher Skizzenbuch von Théodore Géricault,Berne 2003.

- ^See (Eitner 1987), pp. 3–4.

- ^See (Eitner 1987), p. 4.

- ^See (Riding 2003), p. 73: "Having studied the painting by candlelight in the confines of Géricault's studio, he walked into the street and broke into a terrified run".

- ^See (Riding 2003), p. 77.

- ^See (Eitner 1987), p. 5.

- ^See (Eitner 1987), pp. 5–6.

- ^Patrick Noon:Crossing the Channel,page 162.Tate Publishing Ltd,2003.

- ^Constable to DelacroixTate Britain2003 exhibition. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^See (Eitner 1987), p. 6.

- ^"Riderless Racers in Rome".The Walters Art Museum.

- ^Pollitt, Ben (9 August 2015)."Théodore Géricault, Portraits of the Insane".smarthistory.org.Retrieved27 October2023.

- ^Burgos JS (2021). "A new portrait by Géricault".The Lancet. Neurology.20(2): 90–91.doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30479-8.PMID33484650.

Works cited[edit]

- Ciofalo, John J. (2009),The Raft: A Play about the Tragic Life of Théodore Géricault

- Eitner, Lorenz(1987), "Theodore Gericault",Introduction,Salander-O'Reilly

- Whitney, Wheelock(1997),Gericault in Italy,New Haven/London:Yale University Press

- Riding, Christine (2003), "The Raft of the Medusa in Britain",Crossing the Channel: British and French Painting in the Age of Romanticism,Tate Publishing

Further reading[edit]

- French painting 1774–1830: the Age of Revolution.New York; Detroit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Detroit Institute of Arts. 1975.(see index)

External links[edit]

Media related toThéodore Géricaultat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toThéodore Géricaultat Wikimedia Commons- Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 768.

- The Zurich Sketchbook by Théodore Géricault

- Géricault Life Magazine

- Théodore Géricaultin American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- 1791 births

- 1824 deaths

- École des Beaux-Arts alumni

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Deaths by horse-riding accident in France

- French male painters

- French romantic painters

- French people of Norman descent

- French printmakers

- French Orientalist painters

- Artists from Rouen

- Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni

- 19th-century French painters

- Romantic painters

- 19th-century French male artists

![Riderless Racers in Rome, 1817 (The Walters Art Museum[16])](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/Th%C3%A9odore_G%C3%A9ricault_-_Riderless_Racers_at_Rome_-_Walters_37189.jpg/200px-Th%C3%A9odore_G%C3%A9ricault_-_Riderless_Racers_at_Rome_-_Walters_37189.jpg)