Gaelic warfare

This article or sectionpossibly containssynthesis of materialwhich does notverifiably mentionorrelateto the main topic.(April 2010) |

Gaelic warfarewas the type ofwarfarepracticed by theGaelic peoples(theIrish,Scottish,andManx), in the pre-modern period.

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Indigenous Gaelic warfare

[edit]Weaponry

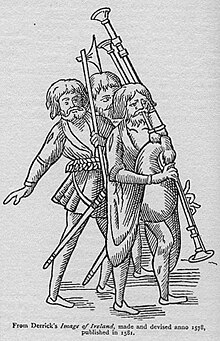

[edit]Irish warfare was for centuries centered on theCeithearn,orKernin English (and so pronounced in Gaelic), lightskirmishing infantrywho harried the enemy with missiles before charging. John Dymmok, serving underElizabeth I'slord-lieutenant of Ireland,described the kerns as:

"... A kind of footman, slightly armed with a sword, atarget(round shield) of wood, or a bow and sheaf of arrows with barbed heads, or else three darts, which they cast with a wonderful facility and nearness... "[1]

For centuries the backbone of any Gaelic Irish army were these lightly armedfoot soldiers.Ceithearnwere usually armed with aspear(gae) orsword(claideamh),long dagger(scian),[2]bow(bogha) and a set ofjavelins,ordarts(gá-ín).[3]

The use ofarmoured infantryinGaelic Irelandfrom the 9th century on, came as a counter to the mail-cladVikings.The arrival of the heavily armouredNorse-GaelicmercenaryGallowglassesin the early 13th century, was in response to theNorman invasion of Irelandand theAnglo-Normansuse of heavily armouredMen-at-armsandKnights.Although the Irish did have knights heavily armored soldiers prior to the gallowglass these were called Ridire in Irish meaning knight as mentioned in theVisio Tnugdali

These adaptations and developments brought regular use of other weapons such aslances,poleaxeslike thedane axe,lochaber axe,sparth axeand swords like thearming swordandtwo-handed swordssimilar to the ScottishClaymore. Many of the medieval swords found in Ireland today are unlikely to be of native manufacture given many of the pommels and cross-guard decoration is not of Gaelic origin.[4]

By the time ofBrian BórumaandMáel Sechnaill,Irish kingswere taking large armies oncampaignover long distances and usingnaval forcesin tandem withland forces.From the 11th century on, kings maintained small permanent fighting forces known aslucht tighe"troops of the household", who were often given houses and land on theking's mensal land.These were well-trained and equipped professional soldiers made up ofinfantryandcavalry.[5]

Aside fromHobelars,who were highly mobile, lightly armoured, cavalryskirmishersandarchers,used primarily forscoutingandambushes,the main Gaeliccavalrywas usually made up of akingorchieftainandhis clan.They usuallyrode without saddlesbut worearmourandiron helmetsand wieldedswords,skenesand longspearsorlances.[6]A fully outfitted medieval Irish army would have includedlight infantry,heavy infantryand mixedcavalry.[7]

Gaelic Warfare was anything but stagnant and was adaptive and ever changing. By the time of theTudor reconquest of Irelandand the beginning of the end of the Gaelic era, the Irish had adopted continental "pike and shot"formations like those used by the continental armies of theSpanish,SwissandGermans.With formations consisting ofpikemenmixed withmusketeersandswordsmen.Indeed, from 1593 to 1601, theGaelic Irishfought with the most up-to-date methods ofwarfare,including full reliance onfirearmsand modern military tactics.[8]

Gaelic raid culture

[edit]

TheGaelic Irishpreferredhit-and-run tacticsandshock tacticslikeambushesandraids(the crech), which involved catching the enemy unaware. One of the most common causes of conflict in Gaelic Ireland was cattle raiding.Cattlewere the main form of wealth in Gaelic Ireland, as it was in many parts of Europe, as currency had not yet been introduced, and the aim of most wars was the capture of the enemy's cattle. If this worked, the raiders would then seize any valuables (mainlylivestock) and potentially valuable hostages, burn the crops, and escape.[10]

Indeed,cattle raidingwas asocial institutionwithin Gaelic culture and newly crownedkingswould carry out raids on traditional rivals upon coronation. TheGaelictermcreach rígh,or "king's raid", was used to describe the event, implying it was a customary tradition.[11]

The cattle raid was often called aTáin Bóand was an important aspect ofGaelic literatureandculture,with theTáin Bó CúailngeandTáin Bó Flidhaisas important examples. Gaelic warfare wasanything but static,asGaelicsoldiers frequentlylootedor bought the newest and most effective weaponry. Although hit-and-run raiding was the preferred Gaelic tactic inmedieval times,there were alsopitched battlesto settle larger disputes.

Especiallyfollowing the arrivalof theVikingsfromLochlann,who brought their own style ofwarfare,raidingandsettlements.Over time thesenewcomersfounded their ownkingdom,began adynastic lineand developed a distinctcultureof their own.

Armour

[edit]

It's often stated that for the most part, the Gaelic Irish fought without armour, instead wearing saffron coloured beltedtunicscalledléine(pronounced 'laynuh'), the plural beingléinte(pronounced 'layntuh/laynchuh'). According toGerald of Waleswho wrote propaganda (in the early 12th century), the Gaels preferred to not wear armour, as they deemed it burdensome to wear and one to be "brave and honourable" to fight without it.[12]Armourwas usually a simple affair: the poorest might have wornpadded coats,the wealthier might have worn boiled leather armour calledcuir bouilli,and the wealthiest might have had access tobronze chest plates,padded textile armouror maybe perhapsmailorscale armours(though they did exist in Ireland, they were quite rare). However this appears to be all incorrect as the Irish did have heavly armored knights as mentioned in theVisio Tnugdalilong before the gallowglass came to Ireland.Gallowglassmercenaries of the early 13th century have been depicted as having wornmail tunicsand steelburgonethelmets but the overall majority ofGaelic warriorswould have been protected only by asmall shield.Gaelicshieldswere usually round, with a spindle shapedBoss,though later the regular iron Boss models were introduced by theAnglo-Saxons,VikingsandNormans.A few shields were also oval in shape or square, but most of the native shields were small and round, likebucklers,to better enable agility and a quick escape.

Customs

[edit]

Clan warfarewas an important aspect of life inGaelic Ireland,especially before theViking Age.WhenVikingsbroughtnew forms of technology,culture,warfareandsettlementsto Ireland.

Before theViking Age,there was a heavy importance placed onGaelic clanwars andritual combat. Another very important aspect of Gaelic ritual warfare at this time wassingle combat.In order to settle a dispute or merely to measure one's prowess, it was customary to challenge another individual warrior from the other army to ritual single combat to the death, while being cheered on by the opposing hosts.

Champion warfarewas an important aspect ofIrish mythology,literatureandculture,particularly in theUlster cyclewithCú ChulainnandtheTáin Bó Cúailnge,where the hero fromUlsterdefeats an entire army fromConnachtone by one. Such single combats were common before apitched battle,and for ritual purposes they tended to occur atriver fords.

The spirit and traditions ofsingle combatwould live on and manifest itself in other ways in Modern Gaelic cultures. InScotlandwith events likeScottish Wrestling,theHighland GamesandScottish Martial Artslike theduelingof the 18th century. Where the victor was determined by who made the first-cut. However, this was not always observed, and at times the duel would continue to the death. InIreland,the spirit of ritual combat has also manifested itself as single combat stylesporting eventsandIrish martial artssuch asIrish bo xing (Dornálaíocht),Irish wrestling (Barróg),stick fighting (Bataireacht)andscuffling (Coiléar agus Uille).

Urban defense

[edit]

Many of the towns in Gaelic Ireland had some type of defense in the form of walls or ditches. For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and buildings werecircularwith conical thatched roofs.[13]Many towns and dwellings in Gaelic Ireland were often surrounded by acircular rampartcalled a "ringfort".[14]There were very few nucleated settlements, but after the 5th century somemonasteriesbecame the heart of small "monastic towns",[15][16]many of theIrish round towerswere built after this period.

Following theNorman invasion of Ireland,theNormansbuiltmotte-and-baileycastles in the areas they occupied,[17]some of which were converted fromringforts.[18]Within Gaelic Ireland, many of the areas conquered byAnglo-Normansoften had defense walls due to the frontier type of lifestyle. Some had these walls built assuming that the town had no adequate defense with only using a ditch. The masonry walls on some towns had not been completed due to the economics of the time. While many of the towns often constructed what looks to be a defensive walls, this can sometimes not be the case. Towns constructed walls and town gates at times as merely a symbol of lordly wealth; or as a physical expression of power, the defensive aspects of some of these walls and gates would become a secondary role.[19]

By the 12th century, "some mottes, especially in frontier areas, had almost certainly been built by the Gaelic Irish in imitation" of the Normans.[20] TheHiberno-Normansgradually replaced these wooden motte-and-baileys withstone castlesandtower houses.[21]Square and rectangle-shaped buildings gradually became more common, and by the 14th or 15th century they had replaced round buildings completely.[22]

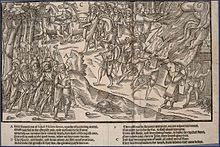

Starting in the late 16th century, an era ofSiege warfarebegan in Ireland. During this period, urban defense came to the forefront of Gaelic warfare and became increasingly important. Following shocking atrocities at theSack of CashelandOliver Cromwell’sSiege and massacre at Drogheda.Gaelic Irish rebels, realizing that they could not expect or trust any quarter to be given upon surrender, began to improvise and set traps for armies besieging their towns.

At both theSiege of ClonmelandSiege of Charlemont,Irishrebel defenders were able exact a heavy toll onEnglishforces. During Clonmel, Cromwell'sNew Model Armyand 8,000 men eventually took the town from its 2,000 Irish defenders, but not before suffering heavy losses of around 2,000 soldiers or a quarter of their total force, their largest ever loss in a single action.[23]At Charlemont, a small force of less than 200 defenders and townsfolk was able to hold off the New Model Army for two months through heavy fighting after arming the entire town's populace including women.[24]In both engagements, the English, with overwhelming forces, surrounded the fortifications and created a breach in the defenses using cannon fire and then assaulted the breach. Both times, the town’s people and defenders set a trap within. At Clonmel, they built acoupurewithin the breach and lined it with artillery, muskets, and pikemen, thus creating akilling fieldjust inside the walls. In both instances, Irish defenders were able to compel the superior English forces into granting surrender agreements with generous terms through heavy fighting and attrition to the besieging armies.[25][26]

Tactics and organisation

[edit]

InitiallyKernorceithernwere members of individual tribes, but later, when theVikingsandEnglishcame to Ireland, they introduced new systems ofbilletingsoldiers, the kern became billetedsoldiersandmercenarieswho served the highest bidder. Because Kern were equipped and trained as lightskirmishers,they faced a severe disadvantage inpitched battle.In battle, the kern and lightly armedhorsemenwould charge the enemy line after intimidating them withshock tactics,war cries,hornsandpipes.[27]

If the kern failed to break an enemy line after the charge, they were liable to flee. If the enemy formation did not break under the kern's charge, then heavily armed and armoured Irish soldiers were moved forward and would advance from the rear lines and attack, these units were replaced in the late 13th century by theGallowglassorGallóglaigh,who at first wereNorse-Gaelicmercenariesbut by the 15th century most largetúathainIrelandhad fostered and developed their own hereditary forces of Gallowglass. The primary function of GaelicHeavy infantrywas so lighter combatants such as Kern and Hobelars caught in thick fighting could strike, break free, re-group and tactically retreat behind the newly formedbattle lineif they needed to.

By the time ofthe Tudor reconquest of Ireland,the forces underHugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyronehad adoptedContinentalpike-and-shottactics. Indeed, from the 16th century on, the Gaelic Irish fought with the most up-to-date methods of warfare, including full reliance on firearms and modern tactics. Their formations consisted of a mix ofPikemen,musketeersandGaelic swordsmenwho beganto be equippedand fight more like the continental units like theGermanLandsknechtor theSpanishRodelero.They used these tactics to fight theinvading English forces,however these formations proved vulnerable without adequatecavalrysupport.Musketsand otherFirearmswere widely used in combination with traditional Gaelicshockandhit and run tactics,often inambushesagainst enemycolumnson the march.[28]

Adaptations

[edit]

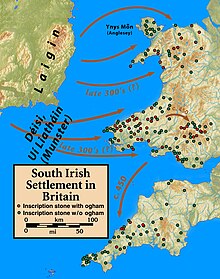

As time went on, the Gaelsbegan intensifyingtheir raids and coloniesinRoman Britain(c. 200–500 AD). Naval forces were necessary for this, and, as a result, large numbers of small boats, calledcurrachs,were employed. Gaelic forces were so frequently at sea (especially theDál RiataGaels), weaponry had to change.Javelinsandslingsbecame more uncommon, as they required too much space to launch, which the small currachs did not allow. Instead, more and more Gaels were armed withbows and arrows.

TheDál Riata,for example, after colonizingthe west of Scotlandand becoming amaritime power,became an army composed completely ofarchers.Slings also went out of use, replaced by both bows and a very effective naval weapon called thecrann tabhaill,a kind ofcatapult.

Later, when theGaelscame into contact with theVikings,they realized the need for heavier weaponry, so as to make hacking through the much largerNorse shieldsand heavy mail-coats possible.

Heavier hacking-swords andpolearmweapons became more frequent, as did Ironhelmetsandmail-coats.Gaels began to regularly use the double-handed "Dane Axe",wielded by theVikings.Irish andScottishinfantry troops fighting with theClaymore,axesandheavier armour,in addition to their ownnative dartsandbows.These heavy troops became known as theGallòglaigh(Gallowglass), or "foreign soldiers",and formed an important part of Gaelic armies in the future.

Thecoming of the Normansinto Irelandand Britainseveral hundred years later also forced theIrishandScotsto use an increasingly large number of more heavily armouredwarriorscombined quickskirmishercavalryin order to effectively deal with the mail-cladNormans.

During theScottish Wars of Independence,theScotshad to develop a means to counter theAnglo-NormanEnglishand their devastating combined use ofheavy cavalryand theLongbow.Which had dominated almost every battlefield inGreat BritainsinceHastings.

The Scottish rebelsAndrew de Moray,William Wallaceand Scottish KingRobert the Brucecan all be credited with the development of theSchiltronas a counter to theNormansand their early use ofcombined armswarfare. English Chroniclers of the era said of the warriors in the Schiltrons:

- "They were all on foot; picked men they were, enthusiastic, armed with keen axes, and other weapons, and with their shields closely locked in front of them, they formed an impenetrable phalanx..."[29]

- "They had axes at their sides and lances in their hands. They advanced like a thick-set hedge and such a phalanx could not easily be broken."[30]

Andrew de Morayis credited with using the Schiltron early on inthe campaignbut he died shortly after sustaining a mortal injury at theBattle of Stirling Bridge.[31][32]

In early engagements, like when Schiltrons were used byWilliam Wallaceat theBattle of Falkirk,the immobilePhalanx-like formations proved vulnerable to the EnglishLongbowmenwithout adequatecavalrysupport. But the Scots learned from this and by the timeEdward IImet the Scots at Bannockburn,Robert the Brucehad adapted theSchiltronand turned it into a more mobile offensive formation (much like the laterPike Squareofcontinental fame). With these tight mobile formations and adequatecavalrysupport. The Scots were able to use this innovative adaptation to pin theEnglish heavy horseagainst theBannockburnon the second day of theBattle of Bannockburnand routed the army ofEdward II of Englandpaving the way for eventualScottish Independence.

Standards and music

[edit]

Many Gaelic clans each had their own distinctcultures,symbols,heraldry,flagsandbattle standards.Wind instruments such as hollowed-out bull horns were often carried into battle byChieftainsor War leaders and used as a means to rally men into combat.Bagpipeswould eventually gain popularity among Gaelic clans and replaced other rallying instruments such as theblowing hornorcarnyx,it can be attributed as being used from as early on as the 14th century. Most notably theGreat Irish Warpipeswhich would go on to be used byGaelic mercenariesin European conflicts and would eventually develop into ceremonial instruments. Bagpipes have since become an important symbol ofGaelic cultureas a whole. With both theUilleann pipesand theGreat Highland Bagpipeplaying important roles in the culture of their respective nations.

Exported Gaelic warfare

[edit]Gallowglass

[edit]

The most prolificNorselegacy in Gaelic warfare was the introduction of theGallowglass,gallóglaigh(Irish) orgallòglaich(Scottish Gaelic), a kind ofheavy infantry,shock troopandelite bodyguardfor theGaelic Nobility.Similar in function to theHousecarlsof theEnglish nobilityor theVarangian GuardofConstantinople.The original Gallowglass wereNorse–Gaelicmercenarieswho came from theHebridesandthe Isles.They appeared in Ireland in the 13th century, following theWars of Scottish Independenceandthe Bruce campaignbut by the 15th century most largetúathahad their own hereditary force of Gallowglass.[35]They fought and trained in a combination ofGaelicandNorsetechniques, and were highly valued; they were hired throughout theBritish Islesat different times, though most famously inIreland.

One of the first battles believed to have to included Gallowglass was theBattle of Connacht.AsÁed na nGall Ó Conchobair,theKing of Connachtwho defeated theAnglo-Normans,was known to travel with a retinue of 160 Gallowglass that he received as a dowry.[36]Gallowglass usually woremailandiron helmetsand wielded heavy weaponry such as theDane axe,Sparth axes,Lochaber axes,Longswords,Claymoresand sometimesspearsorlances.TheseGallóglaighfurnished the retreating Gaels with a "movingline of defensefrom which the horsemen could make short, sharp charges, and behind which they could retreat when pursued ". Their heavy armour made them less nimble thankern,so they were sometimes placed at strategic spots along theline of retreat.[37]

Gallowglasses were frequently hired and served asmercenariesincontinentalarmies and units, such as theDutch Blue Guards,Swiss Guard,theFrenchScottish Guard,and the forces of KingGustavus Adolphus of Swedenin his invasion ofLivoniaduring theThirty Years' War.Gallowglass later became a caste of warrior rather than a indicator of a norse gaelic origin, with Irish Gallowglass clans producing their own.

Despite the increased usage offirearmsin Irish warfare following the 16th century, Gallowglass remained an integral part ofHugh Ó Neill's forces during theNine Years' War.Following the combined Irish defeat at theBattle of Kinsalein 1601, the recruitment of the heavily armoured warriors finally waned.

Hobelars

[edit]Hobelarswere a mounted, highly mobileskirmisherunit. Some weremounted archers,some were merelylight cavalry.These Gaelic horsemen were utilitarian and could fill multiple roles on the battlefield, including as mobile skirmisherinfantryused tooutmaneuverenemy units or that of skirmishercavalry,used forquick and abrupt attacks.

Early Hobelars wore little armour, they typically rode on smaller quicker unarmouredhobby horsesandponiesrather than the full sized horses thatMen-at-armsrode. Hobelars would typically dismount to fight, harry their opponents and then utilize their mounts as a quick getaway. As time went on, Hobelars began to be utilized for more and more cavalry tasks and functions.[38]

During hisconflicts with the English crown,Robert the Brucedeployed thehobbyfor his campaign ofguerilla warfareand mountedraidsto great success, covering 60 to 70 miles (100 to 110 km) a day. They were so successful thatEdward I of Englandprevented IrishexportsofhobbiestoScotlandin order to gain an advantage in the conflict.[39] Hobelars were highly proficient atscouting,patrollingandambushingin areas typically unreachable by cavalry units such a mountainous areas, thick forests and boggy swamps.[40]WithinIrelandandGreat Britainand beyond,the skirmisher cavalry were a well-known and highly valued as a light and mobile unit.

After the successful and effective deployment of these horsemen by both the English and Scottish during theScottish Wars of Independence.[41]Belligerents incontinental conflictsalso began to hireIrishandScottishGaels asmercenarytroops for their armies. Both theEnglishandFrenchhired these Gaelic horsemen and both eventually duplicated the concept themselves.[42]Hobelars were principally utilized in engagements during theScottish Wars of IndependenceandHundred Years' War.After time the Hobelars slowly adapted from mountedskirmishersmuch likekerninto a more basic form oflight cavalry.Onthe continent,from 1311 on continental Hobelars became more and morearmouredand less distinguishable from othercavalryunits.[43]

InScotland,Hobelars served as the offensive arm of castlegarrisons.Hobelars were utilized as raiders across the border by both theEnglishandScots,they can be viewed as early predecessors tothe reiversandmoss-troopersof theScottish borderlands.[44]

Later Weaponry

[edit]

During theLate Middle AgesandRenaissanceperiod, weapon imports fromEuropeinfluenced Gaelic weapon design. Take for example the GermanZweihändersword, a longdouble-handed weaponused for quick, powerful cuts and thrusts. Irish swords were copied from these models, which had unique furnishings. Many, for example, often featuredopen ringson thepommel.On any locally designed Irish sword in the Middle Ages, this meant you could see the end of thetanggo through the pommel and cap the end. These swords were often of very fine construction and quality.Scottish swordscontinued to use the more traditional "V" cross-guards that had been on pre-Norse Gaelic swords, culminating in such pieces as the now famous "claymore"design. This was an outgrowth of numerous earlier designs, and has become a symbol of Scotland. The claymore was used together with the typicalaxesof theGallowglassuntil the 18th century, but began to be replaced bypistols,musketsandbasket-hilted swords,which were shorter versions of the claymore which were used with one hand in conjunction with a shield. Thesebasket-hilted broadswordsare still a symbol ofScotlandto this day, as is the typical small round shield known as a "targe."

Redshanks

[edit]

Redshankwas a nickname for Scottish or Ulstermercenariesfrom theHighlandsandWestern Islescontracted to fight inIreland;they were a prominent feature of Irish armies throughout the 16th century. They were called redshanks because similarly to the Irish they went dressed inplaidsand waded bare-legged through rivers in the coldest weather. The term was not derogatory however, as theEnglishwere in general impressed with the redshanks' qualities as soldiers.[45]

The redshanks were usually armed alike, principally withbows(theshort bowof Scotland and Ireland, rather than thelongbowof Wales and England) and, initially, two-handed weapons likeclaymores,battle axesorLochaber axes.Englishobservers reported that someHighlandersfighting inIrelandworechain mail,long obsolete elsewhere.[46]

Later in the period, they may have adopted thetargeandsingle-handed broadsword,a style of weaponry originally fashionable in early16th-century Spainfrom where its use could have spread toIreland.[47]Combined with the use ofmuskets,this could have influenced the development of what was later referred to as the "highland charge",a tactic of firing a single coordinated musket volley before closing at a run withswordandtarge.[48]ManyGaelic clanlevies, calledCaterans,would have remained relatively poorly armed.

By the mid-17th century, a large number ofScottish Highlanders,also often called "redshanks",fought in theIrish Confederate Wars,notably the clansmen serving underAlasdair Mac Colla,himself a member of a minor Hebridean branch ofClan Donald(a cadet family ofClan MacDonald of Dunnyveg).[49]However, the Highlanders who fought at theBattle of Dungan's HillandBattle of Knocknanusswere to be the last of the redshanks.[50]

The subsequentCromwellian conquestandWilliamite Warbrought an end to Irish employment of Scottish Highlandmercenariesthrough the destruction of their employers, theGaelic nobilityand by the pacification of theScottish Gaelswith theStatutes of Ionaand theHighland clearances.

List of Gaelic conflicts and battles

[edit]This is a list of battles or conflicts in which theGaelshad a leading or crucial role.

- 106 CE:Magh Line

- 157 CE:Battle of Tuath Amrois

- 195 CE:Battle of Maigh Mucruimhe

- 225 CE:Battle of Crinna

- 283 CE:Cath Gabhra

- 331 CE:Achaidh Leithdeircc

- 493 CE:Battle for the Body of St. Patrick

- 596 CE:Battle of Raith

- 561 CE:Battle of Cúl Dreimhne

- 603 CE:Battle of Degsastan

- 629 CE:Battle of Fid Eoin

- 637 CE:Battle of Moira

- 735 CE:Óengus campaigns against Dál Riata

- 736 CE:Battle of Cnoc Coirpi

- 741 CE:Battle of Druimm Cathmail

- 841 CE:MacAlpin's treason

- 795 CE:Early Viking raids in Ireland

- 868 CE:Battle of Cell Ua nDaigri

- 877 CE:Battle of Strangford Lough

- 908 CE:Battle of Ballaghmoon

- 915 CE:Battle of Confey

- 917 CE:Battle of Mag Femen

- 919 CE:Battle of Islandbridge

- 968 CE:Battle of Sulcoit

- 968 CE:Burning of Luimnech

- 977 CE:Battle of Cathair Cuan

- 978 CE:Battle of Belach Lechta

- 980 CE:Battle of Tara

- 999 CE:Battle of Glenmama

- 1014 CE:Battle of Clontarf

- 1130 CE:Battle of Stracathro

- 1132 CE:O'Brian's Siege of Galway

- 1149 CE:O'Brian's second Siege of Galway

- 1151 CE:Battle of Móin Mhór

- 1164 CE:Battle of Renfrew

- 1169 CE:Siege of Wexford

- 1171 CE:Siege of Dublin

- 1174 CE:Battle of Thurles

- 1185 CE:Prince John's Expedition

- 1230 CE:De Burgh's siege of Galway

- 1234 CE:Battle of the Curragh

- 1245 CE:Battle of Embo

- 1247 CE:Battle of Ballyshannon

- 1247 CE:Sack of Dun Gallimhe

- 1249 CE:First Battle of Athenry

- 1256 CE:Battle of Magh Slecht

- 1257 CE:Battle of Creadran Cille

- 1260 CE:Battle of Down

- 1261 CE:Battle of Callann

- 1262 CE:Battle of Tooreencormick

- 1263 CE:Battle of Largs

- 1270 CE:Battle of Connacht

- 1275 CE:Manx revolt

- 1275 CE:Battle of Ronaldsway

- 1294 CE:Battle of Red Ford

- 1296 CE:Sack of Berwick

- 1297 CE:Lanark

- 1297 CE:Raid on Scone

- 1297 CE:Battle of Stirling Bridge

- 1298 CE:Battle of Falkirk

- 1303 CE:Battle of Roslin

- 1304 CE:Battle of Happrew

- 1304 CE:Siege at Stirling Castle

- 1304 CE:Earnside

- 1306 CE:Battle of Dalrigh

- 1307 CE:Battle of Loch Ryan

- 1307 CE:Battle of Turnberry

- 1307 CE:Battle of Glen Trool

- 1307 CE:Battle of Loudoun Hill

- 1307 CE:Battle of Slioch

- 1308 CE:Battle of Barra

- 1308 CE:Harrying of Buchan

- 1308 CE:Battle of the River Dee

- 1308 CE:Battle of the Pass of Brander

- 1314 CE:Capture of Roxburgh

- 1314 CE:Battle of Bannockburn

- 1315 CE:Battle of Moiry Pass

- 1315 CE:Battle of Connor

- 1315 CE:Battle of Kells

- 1316 CE:Battle of Skerries

- 1316 CE:Second Battle of Athenry

- 1317 CE:Battle of Lough Raska

- 1318 CE:Battle of Dysert O'Dea

- 1318 CE:Battle of Faughart

- 1327 CE:Battle of Fiodh-an-Átha

- 1328 CE:Battle of Thomond

- 1329 CE:Braganstown massacre

- 1329 CE:Battle of Ardnocher

- 1337 CE:Battle of Drumlui

- 1370 CE:Battle of Invernahavon

- 1385 CE:Battle of Tochar Cruachain-Bri-Ele

- 1391 CE:Raid of Angus

- 1394 CE:Battle of Ros-Mhic-Thriúin

- 1396 CE:Battle of the North Inch

- 1399 CE:Battle of Tragh-Bhaile

- 1402 CE:Battle of Drumoak

- 1406 CE:Battle of Cluain Immorrais

- 1406 CE:Battle of Tuiteam Tarbhach

- 1411 CE:Battle of Dingwall

- 1411 CE:Battle of Harlaw

- 1426 CE:Battle of Harpsdale

- 1429 CE:Battle of Lochaber

- 1429 CE:Battle of Mamsha

- 1429 CE:Battle of Palm Sunday

- 1429 CE:Siege of Inverness

- 1430 CE:Battle of Drumnacoub

- 1431 CE:Battle of Inverlochy

- 1437 CE:Sandside Chase

- 1438 CE:Battle of Tannach

- 1439 CE:Battle of Craignaught Hill

- 1441 CE:Battle of Craig Cailloch

- 1445 CE:Battle of Arbroath

- 1452 CE:Battle of Bealach nam Broig

- 1452 CE:Battle of Brechin

- 1454 CE:Battle of Clachnaharry

- 1455 CE:Battle of Arkinholm

- 1470 CE:Battle of Corpach

- 1478 CE:Battle of Champions

- 1480 CE:Battle of Bloody Bay

- 1480 CE:Battle of Lagabraad

- 1480 CE:Battle of Skibo and Strathfleet

- 1485 CE:Battle of Blar Na Pairce

- 1486 CE:Battle of Tarbat

- 1487 CE:Battle of Aldy Charrish

- 1490 CE:Massacre of Monzievaird

- 1491 CE:Battle of Blar Na Pairce

- 1491 CE:Raid on Ross

- 1497 CE:Battle of Drumchatt

- 1499 CE:Battle of Daltullich

- 1501 CE:Dubh's Rebellion

- 1504 CE:Battle of Knockdoe

- 1504 CE:Cairnburgh Castle

- 1505 CE:Achnashellach

- 1513 CE:Battle of Glendale

- 1522 CE:Battle of Knockavoe

- 1534 CE:Kildare rebellion

- 1539 CE:Battle of Belahoe

- 1544 CE:Battle of the Shirts

- 1544 CE:Raids of Urquhart

- 1559 CE:Battle of Spancel Hill

- 1569 CE:First Desmond Rebellion

- 1565 CE:Battle of Glentaisie

- 1567 CE:Battle of Farsetmore

- 1570 CE:Battle of Bun Garbhain

- 1570 CE:Battle of Torran-Roy

- 1572 CE:Sack of Athenry

- 1574 CE:Clandeboye massacre

- 1575 CE:Rathlin Island massacre

- 1577 CE:Sack of Eigg[broken anchor]

- 1577 CE:Massacre of Mullaghmast

- 1578 CE:Battle of the Spoiling Dyke

- 1579 CE:Second Desmond Rebellion

- 1580 CE:Battle of Glenmalure

- 1580 CE:Siege of Carrigafoyle Castle

- 1580 CE:Siege of Smerwick

- 1585 CE:Battle of the Western Isles

- 1590 CE:Battle of Doire Leathan

- 1590 CE:Battle of Clynetradwell

- 1593 CE:Battle of Belleek

- 1594 CE:Siege of Enniskillen

- 1594 CE:Battle of the Ford of the Biscuits

- 1594 CE:Battle of Glenlivet

- 1595 CE:Assault on the Blackwater Fort

- 1595 CE:Battle of Clontibret

- 1596 CE:O'Donnell's Siege of Galway

- 1597 CE:Dublin gunpowder explosion

- 1597 CE:Battle of Carrickfergus

- 1598 CE:Battle of Traigh Ghruinneart

- 1598 CE:Battle of Benbigrie

- 1598 CE:Battle of the Yellow Ford

- 1599 CE:Battle of Deputy's Pass

- 1599 CE:Siege of Cahir Castle

- 1600 CE:Battle of Curlew Pass

- 1600 CE:Battle of Moyry Pass

- 1600 CE:Battle of Lifford

- 1601 CE:Battle of Carinish

- 1601 CE:Battle of Coire Na Creiche

- 1601 CE:Siege of Donegal

- 1601 CE:Siege of Kinsale

- 1601 CE:Battle of Castlehaven

- 1602 CE:Siege of Dunboy

- 1602 CE:Dursey massacre

- 1602 CE:Burning of Dungannon

- 1641 CE:Irish Rebellion of 1641

- 1641 CE:Portadown massacre

- 1641 CE:Siege of Drogheda

- 1641 CE:Battle of Julianstown

- 1642 CE:Battle of Kilrush

- 1642 CE:Rathlin Island Massacre

- 1645 CE:Battle of the Braes of Strathdearn

- 1645 CE:Battle of Inverlochy

- 1646 CE:Battle of Benburb

- 1646 CE:Battle of Lagganmore

- 1646 CE:Dunoon massacre

- 1646 CE:Battle of Rhunahaorine Moss

- 1647 CE:Sack of Cashel

- 1647 CE:Battle of Dunaverty

- 1649 CE:Drogheda Massacre

- 1650 CE:Siege of Clonmel

- 1650 CE:Siege of Charlemont

- 1655 CE:Stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig

- 1680 CE:Battle of Altimarlach

- 1688 CE:Battle of Mulroy

- 1692 CE:Massacre of Glencoe

- 1715 CE:Siege of Brahan

- 1715 CE:Battle of Sheriffmuir

- 1719 CE:Capture of Eilean Donan Castle

- 1719 CE:Battle of Glen Shiel

- 1721 CE:Battle of Glen Affric

- 1721 CE:Battle of Coille Bhan

- 1745 CE:Highbridge Skirmish

- 1745 CE:First Siege of Ruthven Barracks

- 1745 CE:Battle of Prestonpans

- 1745 CE:Siege of Culloden House

- 1745 CE:First Siege of Carlisle

- 1745 CE:Clifton Moor Skirmish

- 1745 CE:Second Siege of Carlisle

- 1745 CE:First Siege of Fort Augustus

- 1745 CE:Battle of Inverurie

- 1746 CE:Battle of Falkirk Muir

- 1746 CE:Siege of Stirling Castle

- 1746 CE:Second Siege of Ruthven Barracks

- 1746 CE:Siege of Inverness

- 1746 CE:Second Siege of Fort Augustus

- 1746 CE:Atholl raids

- 1746 CE:Siege of Blair Castle

- 1746 CE:Skirmish of Keith

- 1746 CE:Siege of Fort William

- 1746 CE:Battle of Dornoch

- 1746 CE:Skirmish of Tongue

- 1746 CE:Battle of Littleferry

- 1746 CE:Battle of Culloden

See also

[edit]- Gaels

- Gaelic Ireland

- Celtic warfare

- Ceithearn(Kern)

- Ceathairne(Cateran)

- Gallóglaigh(Gallowglass)

- Hobelar

- Fianna

- Redshank

- Military History

- Warfare in Medieval Scotland

Notes

[edit]- ^Fergus Cannan, 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 14–17

- ^Sgian-dubh

- ^'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 17

- ^Halpin, Andrew (1986). "Irish Medieval Swords c. 1170–1600".Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature.86C:183–230.JSTOR25506140.

- ^Duffy, Seán, ed. (2005). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-135-94824-5.

- ^Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^Flanagan, Marie Therese (1996). "Warfare in Twelfth-Century Ireland". A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–75.

- ^G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601." Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255

- ^E. Estyn Evans, The Personality of Ireland, Cambridge University Press (1973),ISBN0-521-02014-X

- ^Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^Shae Clancy."Cattle in Early Ireland".Celtic Well.Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^The Topography of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine (English translation)

- ^Joyce, Patrick Weston (1906). "Chapter XVI: The House, Construction, Shape, and Size". A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. Library Ireland. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^Connolly, Sean J (2007). "Chapter 2: Late Medieval Ireland: The Irish". Contested island: Ireland 1460–1630. Oxford University Press. pp. 20–24.

- ^Connolly, Sean J (2007). "Chapter 2: Late Medieval Ireland: The Irish". Contested island: Ireland 1460–1630. Oxford University Press. pp. 20–24.

- ^O'Keeffe, Tadhg (1995). Rural settlement and cultural identity in Gaelic Ireland (PDF). Ruralia 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^Glasscock, Robin Edgar (2008) [1987]. "Chapter 8: Land and people, c.1300". In Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0009.

- ^O'Keeffe, Tadhg (1995). Rural settlement and cultural identity in Gaelic Ireland (PDF). Ruralia 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^McKeon, Jim (2011). "Urban Defences in Anglo-Norman Ireland: Evidence from South Connacht". Eolas: The Journal of the American Society of Irish Medieval Studies. 5: 146–190. JSTOR 41585270.

- ^Glasscock, Robin Edgar (2008) [1987]. "Chapter 8: Land and people, c.1300". In Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0009.

- ^Glasscock, Robin Edgar (2008) [1987]. "Chapter 8: Land and people, c.1300". In Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0009.

- ^Joyce, Patrick Weston (1906). "Chapter XVI: The House, Construction, Shape, and Size". A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. Library Ireland. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^Plant, David (28 February 2008). "The Siege of Clonmel, 1650". BCW Project. David Plant. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^Manning, Roger (2000). An Apprenticeship in Arms: The Origins of the British Army 1585-1702. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^Wheeler, James Scott (1999). Cromwell in Ireland. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 0-7171-2884-9.

- ^"Clonmel: Its Monastery, and Siege by Cromwell". Duffy's Hibernian Magazine. III (14). August 1861. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^Fergus Cannan, 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 17

- ^G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601." Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255

- ^Trokelowe, quoted in Brown, op.cit, p. 90

- ^Vita Edwardi Secundi, quoted in Brown, Chris (2008). Bannockburn 1314. Stroud: History press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7524-4600-4.

- ^Duncan, A.A.M. (2007). Cowan, Edward (ed.). William, Son of Alan Wallace: The Documents, in The Wallace Book. Edinburgh: John Donald. p. 42.ISBN9781906566241.

- ^Watson, Fiona (2007). Cowan, Edward (ed.). Sir William Wallace: What We Do – and Don't – Know, in The Wallace Book. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 31–34.ISBN9781906566241.

- ^Halpin; Newman (2006) p. 244; Simms (1998) p. 78; Simms (1997) pp. 111 fig. 5.3, 114 fig. 5.6; Halpin (1986) p. 205; Crawford, HS (1924).

- ^Halpin; Newman (2006) p. 244; Verstraten (2002) p. 11; Crawford, HS (1924).

- ^Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^Duffy. The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. 2007 p. 1.

- ^Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268,Hobelars

- ^Hyland (1998), p 32, 14, 37

- ^The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268,Hobelars

- ^Hyland (1998), p 32, 14, 37

- ^Lydon (1954)

- ^The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268,Hobelars

- ^The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology,Volume 1, Page 267-268,Hobelars

- ^Falls, Elizabeth's Irish Wars, p.79

- ^Fforde, The Great Glen, 2011

- ^Stevenson, Alasdair MacColla and the Highland Problem in the Seventeenth Century, 1980, p.83

- ^Stevenson, Scottish Covenanters and Irish Confederates, 1981, p.4

- ^Hill, James Michael, Celtic warfare, 1595–1763 (2003),J. Donald

- ^Carlton, Charles (2002). Going to the Wars: The Experience of the British Civil Wars 1638–1651. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-84935-2., page 135

References

[edit]- G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601".Irish Historical Studies,Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255–279

- Fergus Cannan, "'HAGS OF HELL': late medieval Irish kern".History Ireland,Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 14–17

- The Barbarians, Terry Jones

- Julius Caesar,"De Bello Gallico"

- "Tain Bo Cuailnge", From theBook of Leinster

- Geoffrey Keating,"History of Ireland"

- "The Wars of the Gaels with the Foreigners"

- http:// myarmoury /feature_armies_irish.html

- http:// myarmoury /feature_armies_scots.html