Garuda Purana

| Part ofa serieson |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

| Part ofa serieson |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

TheGaruda Puranais one of 18Mahāpurāṇatexts inHinduism.It is a part of theVaishnavismliterature corpus,[1]primarily centering around the Hindu godVishnu.[2]It was composed inSanskritand is today also available in various languages like Gujarati[3]and English. The earliest version of the text may have been composed in the first millennium CE,[4]but it was likely expanded and changed over a long period of time.[5][6]

TheGaruda Puranatext, known in many versions, contains more than 15,000 verses.[contradictory][6][7]Its chapters encyclopedically deal with a highly diverse collection of topics,[8]includingcosmology,mythology,relationship between gods, ethics, good versus evil, variousschools of Hindu philosophies,the theory ofYoga,the theory of "heaven and hell" with "karma and rebirth", ancestral rites, andsoteriology;rivers and geography, types of minerals and stones, testing methods for gems for their quality; listing of plants and herbs,[9]various diseases and their symptoms, various medicines, aphrodisiacs, and prophylactics; astronomy, astrology, the moon and planets, and theHindu calendarand its basis; architecture, home building, and essential features of aHindu temple;rites of passage, charity and gift making, economy, thrift, duties of a king, politics, state officials and their roles and how to appoint them; genres of literature, and rules of grammar.[2][7][10]The final chapters discuss how to practice Yoga (Samkhya and Advaita types), personal development, and the benefits of self-knowledge.[2]

ThePadma Puranacategorizes theGaruda Purana—along with theBhagavata Purana,theVishnu Purana,and itself—as aSattvaPurana (a Purana that represents goodness and purity).[11]The text, like all Mahapuranas, is attributed to the sageVeda Vyāsain the Hindu tradition.[12]

History[edit]

According to Pintchman, the text was composed sometime in the first millennium CE, but likely compiled and changed over a long period of time.[5]Gietz et al. place the first version of the text only between the fourth and eleventh centuries CE.[4]

Leadbeater states that the text is likely from about 900 CE, given that it includes chapters onYogaandTantratechniques that likely developed later.[13]Other scholars suggest that the earliest core of the text may be from the first centuries of the common era, and additional chapters were added thereafter through the sixth century or later.[14]

The version of theGaruda Puranathat survives into the modern era, states Dalal, is likely from 800 to 1000 CE, with sections added in the 2nd millennium.[6]Pintchman suggests 850 to 1000 CE.[15]Chaudhuri and Banerjee, as well as Hazra, on the other hand, state that it cannot be from before about the tenth or eleventh century CE.[14]

The text exists in many versions, with varying numbers of chapters and considerably different content.[6][7][12]SomeGaruda Puranamanuscripts have been known by the titles "Sauparna Purana"(mentioned inBhagavata Puranasection 12.13), "Tarksya Purana"(the Persian scholarAl-Biruniwho visited India mentions this name), and "Vainateya Purana"(mentioned inVayu Puranasections 2.42 and 104.8).[7]

The bookGarudapuranasaroddhara,translated by Ernest Wood and SV Subrahmanyam, appeared in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[16][17]This, statesLudo Rocher,created major confusion because it was mistaken for theGaruda Purana,a misidentification first discovered byAlbrecht Weber.[16]Garuda-purana-saroddharais actually the originalbhasyawork (commentary) of Naunidhirama, which cites a section of the now nonexistent version ofGaruda Puranaas well as other Indian texts.[16]The earliest translation of one version of theGaruda Purana,by Manmatha Nath Dutt, was published in the early twentieth century.[2]

Structure[edit]

TheGaruda Puranais aVaishnavaPurana and has, according to the tradition, 19,000 shlokas (verses).[6]However, the manuscripts that have survived into the modern era have preserved about 8,000 verses.[6]These are divided into two parts: aPurvakhanda(early section) and anUttarakhanda(later section, more often known asPretakhandaorPretakalpa[14]). The Purvakhanda contains about 229 chapters, but in some versions of the text this section has between 240–243 chapters.[7]The Uttarakhanda varies between 34 and 49 chapters.[7]The Venkatesvara Edition of the Purana has an additional Khanda namedBrahmakhanda.[18]

TheGaruda Puranawas likely fashioned after theAgni Purana,the other major medieval India encyclopedia that has survived.[7]The text's structure is idiosyncratic, in that it is a medley, and does not follow the theoretical structure expected in a historic puranic genre of Indian literature.[7]It is presented as information thatGaruda(the man-bird vehicle of Vishnu) learned from Vishnu and then narrated to the sageKashyapa,which then spread in the mythical forest of Naimisha to reach the sage Vyasa.[6]

Contents: Purvakhanda[edit]

The largest section (90%) of the text is Purvakhanda, which discusses a wide range of topics associated with life and living. The remaining is Pretakhanda, which deals primarily with rituals associated with death and cremation.[7]

Cosmology[edit]

The cosmology presented inGaruda Puranarevolves aroundVishnuandLakshmi,and it is their union that created the universe.[19]Vishnu is the unchanging reality calledBrahman,while Lakshmi is the changing reality calledMaya.[19]The goddess is the material cause of the universe, the god acts to begin the process.[19]

Like other Puranas, the cosmogenesis inGaruda Puranaweaves theSamkhyatheory of two realities—thePurusha(spirit) andPrakriti(matter), the masculine and feminine—presented as interdependent, each playing a different but essential role to create the observed universe.[20]Goddess Lakshmi is the creative power of Prakriti, the cosmic seed and the source of creation.[20]God Vishnu is the substance of Purusha, the soul and the constant.[20]Pintchman states that the masculine and the feminine are presented by theGaruda Puranaas inseparable aspects of the same divine, metaphysical truthBrahman.[15]

Madan states that theGaruda Puranaelaborates the repeatedly found theme in Hindu religious thought that the living body is a microcosm of the universe, governed by the same laws and made out of the same substances.[21]All the gods are inside the human body; what is outside the body is present within it as well.[21]Body and cosmos, states Madan, are equated in this theme.[21]Vishnu is presented by the text as the supreme soul within the body.[22][23]

Deity worship[edit]

The text describes Vishnu, Vaishnava festivals andpuja(worship), and offersmahatmya(a pilgrimage tour guide)[24]to Vishnu-related sacred places.[6][25]However, theGaruda Puranaalso includes significant sections with reverence forShaiva,Shakti,andSmartatraditions, including thePanchayatana pujaof Vishnu, Shiva, Durga, Surya (Sun), and Ganesha.[6][26]

Features of a temple[edit]

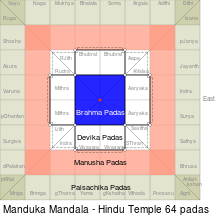

TheGaruda Puranaincludes chapters on the architecture and design of a temple.[27][28]It describes recommended layouts and dimensional ratios for design and construction.

In the first design, it recommends that a plot of ground should be divided into a grid of 8×8 (64) squares, with the four innermost squares forming thechatuskon(adytum).[27]The core of the temple, states the text, should be reachable through 12 entrances, and the walls of the temple raised touching the 48 of the squares.[27]The height of the temple plinth should be based on the length of the platform, the vault in the inner sanctum should be co-extensive with adytum's length with the indents therein set at a third and a fifth ratio of the inner vault's chord.[27]The arc should be half the height of pinnacle, and the text describes various ratios of the temple's exterior to the adytum, those within adytum and then that of the floor plan to thevimana(spire).[27][28]

The second design details a 16 square grid, with four inner squares (pada) for the adytum.[27]The text thereafter presents the various ratios for the temple design.[27]The dimensions of the carvings and images on the walls, edifices, pillars and themurtiare recommended by the text to be certain harmonic proportions of the layout (length of apada), the adytum and the spire.[27][28]

The text asserts that temples exist in many thematic forms.[27]These include thebairaja(rectangle themed),puspakaksa(quadrilateral themed),kailasha(circular themed),malikahvaya(segments of sphere themed), andtripistapam(octagon themed).[27]The text claims these five themes create 45 different styles of temples, from the Meru style to Shrivatsa style. Each thematic form of temple architecture permits nine styles of temples, and the Purana lists all 45 styles.[27]It also states that within these various temple styles, the inner edifice is best in five shapes: triangle, lotus-shaped, crescent, rectangular, and octagonal.[27]The text thereafter describes the design guidelines for theMandapaand theGarbha Griha.[27][28][29]

The temple design, states Jonathan Parry, follows the homology at the foundation of Hindu thought, that the cosmos and body are harmonious correspondence of each other; the temple is a model and reminder of this cosmic homology.[30]

Gemology[edit]

Gems: how to buy them?

First the shape, color, defects or excellences of a gem should be carefully tested and then its price should be ascertained in consultation with a gem expert who has studied all the books dealing with the precious stones.

—Garuda Purana,Purvakhanda, chapter 68

(translator: MN Dutt)[31]

TheGaruda Puranadescribes 14 gems, their varieties, and how to test their quality.[10][32]The gems discussed includeruby,pearl,yellowsapphire,hessonite,emerald,diamond,cats eye,blue sapphire,coral,redgarnet,jade,colorlessquartz,andbloodstone.The technical discussion of gems in the text is woven with its theories on the mythical creation of each gem, astrological significance, and talisman benefits.[32][33]

The text describes the characteristics of the gems, how to clean and make jewelry from them, and cautions that gem experts should be consulted before buying them.[34]For example, it describes usingjamverafruit juice (containslime) mixed with boiled rice starch in order to clean and soften pearls, then piercing them to make holes for jewelry.[34]A sequentialvitanapattimethod of cleaning, states the text—wherein the pearls are cleaned with hot water, wine, and milk—gives the best results.[34]It also describes a friction test by which pearls should be examined.[34]Similar procedures and tests are described for emerald, jade, diamonds, and all other gems included in the text.[32]

Laws of virtue[edit]

Chapter 93 of theGaruda Purvakhandapresents sage Yajnavalkya's theory on laws of virtue. The text asserts that knowledge is condensed in theVedas,in texts of different schools of philosophy such asNyayaandMimamsa,in theShastrasondharma,on making money and temporal sciences written by 14 holy sages.[35]Thereafter, through Yajnavalkya, the text presents its laws of virtue. The first one it lists isdāna(charity), which it defines as:

A gift, made at a proper time and place, to a deserving person, in a true spirit of compassionate sympathy, carries the merit of all sorts of pious acts.

— Garuda Purana,chapter 93[36]

The text similarly discusses the following virtues—right conduct,damah(self-restraint),ahimsa(non-killing, non-violence in actions, words, and thoughts), studying theVedas,and performingrites of passage.[37][38]The text presents different set of diet and rites of passage rules based on thevarna(social class) of a person.[37]TheBrahmin,for example, is advised to forgo killing animals and eating meat, while it is suggested to undertakeUpanayana(holy thread ceremony) at the youngest age. No dietary rules are advised forShudra,nor is the thread ceremony discussed.[37][38]In one version of theGaruda Purana,these chapters on laws of virtue are borrowed from and duplicates of nearly 500 verses found in theYajnavalkya Smriti.[38][39]The various versions ofGaruda Puranashow significant variations.[7][12][38]

TheGaruda Puranaasserts that the highest and most imperative religious duty is to introspect into one's own soul, seeking self-communion.[36]

Ethics (Nityaachaara)[edit]

The chapter 108 and thereafter, presentGaruda Purana's theories onNityaachaara(नित्याचार,lit. 'ethics and right conduct') towards others.[40][38]

Quit the country where you can find neither friends nor pleasures, nor in which there is any knowledge to be gained.

— Garuda Purana,chapter 109[41]

Ethics

Little by little a man should acquire learning.

Little by little a mountain should be climbed.

Little by little desires should be gratified.

—Garuda Purana,Purvakhanda, chapter 109

(translator: MN Dutt)[42]

TheGaruda Puranaasserts: save money for times of distress, but be willing to give it up all to save your wife.[38]It is prudent to sacrifice oneself to save a family, and it is prudent to sacrifice one family to save a village.[38]It is prudent to save a country if left with a choice to save the country or a village.[38][43]Yet, in verses that follow, it says a man should renounce that country whose inhabitants champion prejudice, and forgo the friend who he discovers to be deceitful.[43]

The text cautions against application of knowledge which is wedded to meanness, against pursuit of physical beauty without ennobling mind, and against making friends with those who abandon their dear ones in adversity.[43]It is the nature of all living beings to pursue one's own self-interest.[38][43]Yet, do not acquire wealth through vicious means or by bowing down to your enemies.[41]

The text also asserts that: men of excellence live with honest means, are true to their wives, pass their time in intellectual pursuits and are hospitable to newcomers.[38][43]Eternal are the rewards when one weds one's knowledge with noble nature, deep is the friendship roused by connection of the soul.[44]The discussion on ethics is mixed in other chapters.[45]

Good government[edit]

Governance is part of the Neeti Shaastra section of theGaruda Purana,and this section influenced later Indian texts on politics and economy.[46]

The Purvakhanda, from chapter 111 onwards, describes the characteristics of a good king and good government.[47]Dharma should guide the king, the rule should be based on truth and justice, and he must protect the country from foreign invaders.[48]Taxation should be bearable, never cause hardship on the merchants or taxpayers, and should be similar in style to one used by the florist who harvests a few flowers without uprooting the plants and while sustaining the future crops.[48]A good government advances order and prosperity for all.[48]

A stable king is one whose kingdom is prosperous, whose treasury is full, and who never chastises his ministers or servants.[49]He secures services from the qualified, honest and virtuous, rejects the incapable, wicked and malicious, states chapter 113.[50]A good government collects taxes like a bee collecting honey from all the flowers when ready and without draining any flower.[50]

Medicine (Dhanvantari Samhita)[edit]

Chapters 146–218 of the Purvakhanda present theDhanvantari Samhita,its treatise on medicine.[51][52]The opening verses assert that the text describes the pathology, pathogeny, and symptoms of all diseases studied by ancient sages, in terms of its causes, incubation stage, manifestation in full form, amelioration, location, diagnosis, and treatment.[53]

Parts of the pathology and medicine-related chapters ofGaruda Purana,states Ludo Rocher, are similar toNidanasthanaof Vagbhata'sAstangahridaya,and these two may be different manuscript recensions of the same underlying but now lost text.[14]Susmita Pande states that other chapters ofGaruda Purana,such as those on nutrition and diet to prevent diseases, are similar to those found in the more ancient Hindu textSushruta Samhita.[51]

The text includes various lists of diseases, agricultural products, herbs, and formulations with claims to medicinal value.[52][51]For example, chapters 202 and 227 of the Purvakhanda list Sanskrit names of over 450 plants and herbs, along with claims to their nutritional or medicinal value.[9][54]

- Veterinary science

The chapter 201 of the text presents veterinary diseases of horses and their treatment.[55]The verses describe various types ofulcersand cutaneous infections in horses, and 42 herbs for veterinary care formulations.[55][56]

Yoga (Brahma Gita)[edit]

The last ten chapters of the Purvakhanda are dedicated toYoga,and are sometimes referred to as theBrahma Gita.[6]This section is notable for references to Hindu deityDattatreyaas theguruof Ashtang (eight-limbed) Yoga.[57]

Mokshais Oneness

The Yogins, through Yoga,

realise their being with the supreme Brahman.

Realization of this is called Mukti.

—Garuda Purana,Purvakhanda, chapter 235

(abridged, translator: MN Dutt)[58]

The text describes a variety ofasanas(postures), then adds that the postures are means, not the goal.[59]The goal of Yoga is meditation,samadhi,and self-knowledge.[59]

Ian Whicher states that theGaruda Puranain chapter 229 recommends usingsagunaVishnu (with form like amurti) in the early stages of Yoga meditation to help concentration and draw in one's attention with the help of the gross form of the object. After this has been mastered, states the text, the meditation should shift fromsagunatonirguna,unto the subtle, abstract formless Vishnu within, with the help of a guru (teacher).[60]These ideas ofGaruda Puranawere influential, and were cited by later texts such as in verse 3.3 of the 17th-centuryArthabodhini.[61]

Contents: Pretakhanda[edit]

The Last Goodbye

Go forth, go forth upon those ancient pathways,

By which your former fathers have departed.

Thou shalt behold god Varuna, and Yama,

both kings, in funeral offerings rejoicing.

Unite thou with the Fathers and with Yama,

withistapurtain the highest heaven.

Leaving behind all blemish homeward return,

United with thine own body, full of vigor.

The second section of the text, also known asUttarakhandaandPretakalpa,includes chapters on funeral rites and life after death. This section was commented upon by Navanidhirama in his publicationGaruda Purana Saroddhara,which was translated by Wood and Subramanyam in 1911.[17]

The text specifies the following for last rites:

A dead child, who died before completing his second year, should be buried instead of being cremated, and no sort of Sraddha or Udaka-kriya is necessary. The friends or relatives of a child, dead after completing its second year of life, shall carry its corpse to the cremation ground and exhume it in fire by mentally reciting the Yama Suktam.

— Rigveda10.14,Garuda Purana[62]

The Pretakhanda is the second and minor part ofGaruda Purana.Rocher states that it is "entirely unsystematic work" presented with motley confusion and many repetitions in the Purana, dealing with "death, the dead and beyond".[64]Monier Monier-Williamswrote in 1891 that portions of verses recited at cremation funerals are perhaps based on this relatively modern section of theGaruda Purana,but added that Hindu funeral practices do not always agree with guidance in theGaruda Purana.[65]Three quite different versions of the Pretakhanda of theGaruda Puranaare known, and the variation between the chapters, states Jonathan Parry, is enormous.[12][6]

The Pretakhanda also talks in details about the various types of hell and the sins that can lead one into them. It gives a detailed description of what a soul goes through after death, having met theyamadutaand the journey tonarakain the year following the death.[66]

Contents: Brahmakhanda[edit]

Available only in the Venkateswara Edition of theGaruda Purana,the Brahmakhanda has 29 chapters in the form of an interlocution betweenKrishnaandGaruda,on the supremacy ofVishnu,the nature and form of other gods, and the description of the shrine ofVenkateshvaraatTirupatiand other Tirthas there.[67]While speaking about the supremacy of Vishnu and the nature of other gods, it criticises some of the Advaitic doctrines (likeUpadhi,Maya,andAvidya)[68]and upholds the doctrine ofMadhvacharya's school;[69]a distinctive feature which is scarcely observed in any other Purana.

The form and the contents of this section prove its later origin, a fact further substantiated by the absence of any reference to this section in other Puranas such as theNarada Purana.[70]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Leadbeater 1927,p. xi.

- ^abcdDutt 1908.

- ^Gretil, H. H.(2020).garuDapurANa.Sanskrit Documents Organisation. p. i. Archived fromthe originalon 2023-04-25.Retrieved2021-04-27.

- ^abK P Gietz 1992,p. 871, item 5003.

- ^abPintchman 2001,pp. 91–92 with note 4.

- ^abcdefghijkDalal 2014,p. 145.

- ^abcdefghijRocher 1986,pp. 175–178.

- ^Rocher 1986,pp. 78–79.

- ^abSensarma P (1992)."Plant names - Sanskrit and Latin".Anc Sci Life.12(1–2): 201–220.PMC3336616.PMID22556589.

- ^abRajendra Chandra Hazra (1938),Some Minor Puranas,Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 69–79

- ^Wilson, H. H.(1840).The Vishnu Purana: A system of Hindu mythology and tradition.Oriental Translation Fund. p. xii.

- ^abcdJonathan Parry (2003). Joanna Overing (ed.).Reason and Morality.Routledge. pp. 209–210.ISBN978-1135800468.

- ^Leadbeater 1927,pp. xi, 102.

- ^abcdRocher 1986,p. 177.

- ^abPintchman 2001,p. 81.

- ^abcRocher 1986,pp. 177–178.

- ^abWood 1911.

- ^"The Garuda Purana Part 1 Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology".

- ^abcPintchman 2001,pp. 81–83.

- ^abcPintchman 2001,pp. 81–83, 88–89.

- ^abcMadan 1988,pp. 356–357.

- ^Shrikala Warrier (2014).Kamandalu: The Seven Sacred Rivers of Hinduism.Mayur University. p. 260.ISBN978-0-9535679-7-3.

- ^T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993).Elements of Hindu iconography.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 129–131, 235.ISBN978-81-208-0878-2.

- ^Ariel Glucklich 2008,p. 146,Quote:The earliest promotional works aimed at tourists from that era were calledmahatmyas.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 23–26, 33–34, 67–76, 102–105, 209–224.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 47–50, 58–64, 90–98.

- ^abcdefghijklmnDutt 1908,pp. 113–117.

- ^abcdKramrisch 1976,pp. 42, 132–134, 189, 237–241 of Volume 1.

- ^Kramrisch 1976,pp. 340–344, 412, 423–424 with footnotes of Volume 2.

- ^Maurice Bloch; Jonathan Parry (1982).Death and the Regeneration of Life.Cambridge University Press. p. 76.ISBN978-1316582299.

- ^Dutt 1908,p. 181.

- ^abcDutt 1908,pp. 180–205.

- ^Richard S. Brown (2008).Ancient Astrological Gemstones & Talismans - 2nd Edition.Hrisikesh Ltd. pp. 61, 64.ISBN978-974-8102-29-0.

- ^abcdDutt 1908,pp. 181, 190–191.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 260–262.

- ^abDutt 1908,p. 261.

- ^abcDutt 1908,pp. 261–265.

- ^abcdefghijLudwik Sternbach (1966), A New Abridged Version of the Bṛhaspati-saṁhitā of the Garuḋa Purāṇa, Journal: Puranam, Volume 8, pp. 315–431

- ^S Vithal (1908)."The Parasariya Dharma Sastra".Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society.XXII.Asiatic Society of Bombay: 342.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 315–352.

- ^abDutt 1908,p. 320.

- ^Dutt 1908,p. 323.

- ^abcdeDutt 1908,p. 319.

- ^Dutt 1908,p. 326.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 336–345,Quote:Nobody is nobody's friend. Nobody is nobody's enemy. Friendship and enmity is bounded by a distinct chain of cause and effect (self-interest). – Chapter 114.

- ^Narayana (Transl: A Haskar) (1998).Hitopadesa.Penguin Books. p. xiv.ISBN978-0144000791.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 328–347.

- ^abcDutt 1908,p. 328.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 329–330.

- ^abDutt 1908,pp. 333–335.

- ^abcSusmita Pande (2008). Vinod Chandra Srivastava (ed.).History of Agriculture in India.Concept. pp. 844–845.ISBN978-81-8069-521-6.

- ^abDutt 1908,pp. 422–676.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 422–423.

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 698–705.

- ^abP Sensarma (1989), Herbal Veterinary Medicines in an ancient Sanskrit Work - The Garuda Purana, Journal of Society of Ethnobotanists, Volumes 1–4, pages 83-88

- ^Dutt 1908,pp. 693–697.

- ^Antonio Rigopoulos (1998).Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara: A Study of the Transformative and Inclusive Character of a Multi-faceted Hindu Deity.State University of New York Press. p. 33.ISBN978-0791436967.

- ^Dutt 1908,p. 747.

- ^abEdwin Francis Bryant; Patañjali (2009).The Yoga sūtras of Patañjali.North Point Press. pp.284–285, 314.ISBN978-0865477360.

- ^Ian Whicher (1998).The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga.State University of New York Press. p. 369.ISBN978-0791438152.

- ^Gerald James Larson; Karl H. Potter (2008).The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Yoga: India's philosophy of meditation.Motilal Banarsidass. p. 349.ISBN978-8120833494.

- ^abDutt 1908,pp. 305–306.

- ^Mariasusai Dhavamony (1999).Hindu Spirituality.Gregorian University Press. p. 270.ISBN978-8876528187.

- ^Rocher 1986,p. 178.

- ^Monier Monier-Williams (1891), Brahmanism and Hinduism, 4th edition, Macmillan & Co, p. 288

- ^The Garuda Purana by Earnest Wood and S.V. Subrahmanyam (1911), Chapter 2: An Account of the Ways of Yama, 2019 edition, Global Grey publication

- ^"Garuda Purana Part 3 Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology".

- ^"Garuda Purana Part 3 Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology".

- ^"Garuda Purana Part 3 Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology".

- ^"Narada Purana ENG 04 1952 OCR Motilal Banasirdass".

Bibliography[edit]

- Dalal, Rosen (2014).Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide.Penguin.ISBN978-8184752779.

- Dutt, Manmatha Nath (1908).The Garuda Puranam.SRIL, Calcutta (archived by Harvard University Library).

- K P Gietz; et al. (1992).Epic and Puranic Bibliography (Up to 1985) Annoted and with Indexes: Part I: A - R, Part II: S - Z, Indexes.Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.ISBN978-3-447-03028-1.

- Ariel Glucklich (2008).The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-971825-2.

- Kramrisch, Stella (1976).The Hindu Temple, Volume 1 & 2.Motilal Banarsidass.ISBN81-208-0223-3.

- Pintchman, Tracy (2001).Seeking Mahadevi: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess.State University of New York Press.ISBN978-0791450086.

- Leadbeater, Charles Webster (1927).The Chakras.Theosophical Publishing House (Reprinted 1972, 1997).ISBN978-0-8356-0422-2.

- Madan, T. N. (1988).Way of Life: King, Householder, Renouncer: Essays in Honour of Louis Dumont.Motilal Banarsidass.ISBN978-81-208-0527-9.

- Rocher, Ludo(1986).The Puranas.Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.ISBN978-3447025225.

- Wood, Ernest and SV Subrahmanyam (1911).The Garuda Purana Saroddhara (of Navanidhirama).SN Vasu (Reprinted by AMS Press, 1974).ISBN0-404578098.

External links[edit]

- [1][The Translated garuda puranam in Tamil]

- The Garuda Purana, full English translation by Dutt, 1908

- The Garuda Puran in English, Hindi and Sanskrit

- The Garuda Purana Saroddhara of Navanidhirama,Translated by Wood and Subrahmanyam, 1911, atsacred-texts