Gastornis

| Gastornis | |

|---|---|

| |

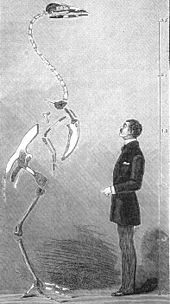

| Mounted skeleton ofG. gigantea | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | †Gastornithiformes |

| Family: | †Gastornithidae Fürbringer,1888 |

| Genus: | †Gastornis Hébert, 1855 (videPrévost, 1855) |

| Type species | |

| †Gastornis parisiensis Hébert, 1855

| |

| Other species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Gastornisis an extinctgenusof large,flightless birdsthat lived during the mid-Paleoceneto mid-Eoceneepochs of thePaleogeneperiod.Fossilshave been found in Europe, Asia and North America, with the North American specimens formerly assigned to the genusDiatryma.

Gastornisspecies were very large birds that were traditionally thought to have been predators of various smallermammals,such as ancient, diminutiveequids.However, several lines of evidence, including the lack of hookedclaws(in knownGastornisfootprints), studies of theirbeakstructure andisotopic signaturesof their bones, have caused scientists to now consider that these birds as probablyherbivorous,feeding on tough plant material and seeds.Gastornisis, generally, agreed to be related to theGalloanserae,the group containingwaterfowlandgamebirds.

History

Gastorniswas first described in1855from a fragmentaryskeleton.It was named afterGaston Planté,described as a "studious young man full of zeal", who had discovered the first fossils inclay(Argile Plastique) formation deposits atMeudon,near Paris.[2]The discovery was notable, due to the large size of the specimens, and because, at the time,Gastornisrepresented one of the oldest known birds.[3]Additional bones of the first known species,G. parisiensis,were found in the mid-1860s.Somewhat more-complete specimens, then referred to the new speciesG. eduardsii(now considered asynonymofG. parisiensis), were found a decade later. These specimens, found in the1870s,formed the basis for a widely- circulated and reproduced skeletal restoration byLemoine.The skulls of these originalGastornisfossils were unknown, other than nondescript fragments and several bones used in Lemoine's illustration, which turned out to be those of other animals.[4]Thus, this European specimen was long reconstructed as a sort of gigantic "crane-like "bird.[5][6]

In1874,the AmericanpaleontologistEdward Drinker Copediscovered another fragmentary set of fossils at theWasatch Formation,New Mexico.Cope considered the fossils to be of a distinct genus and species of giant ground bird; in1876,he named the remainsDiatryma gigantea(/ˌdaɪ.əˈtraɪmə/DY-ə-TRY-mə),[7]from theAncient Greekδιάτρημα (diatrema), meaning "through a hole", in reference to the large foramina (perforations) that penetrated some of the foot bones.[8][9]In1894,a singlegastornithidtoe bonefromNew Jerseywas described by Cope's "rival"Othniel Charles Marsh,and classified as a new genus and species:Barornis regens.In1911,it was recognized that this, too, could be considered a junior synonym ofDiatryma(and therefore, later,Gastornis).[10]Additional, fragmentary specimens were found inWyomingin 1911, and assigned (in1913) to the new speciesDiatryma ajax(also now considered a synonym ofG. gigantea).[10]In1916,anAmerican Museum of Natural Historyexpedition to theBighorn Basin(Willwood Formation,Wyoming) found the first nearly-complete skull and skeleton, which was described in1917and gave scientists their first clear picture of the bird.[10]Matthew, Granger, and Stein (1917) classified this specimen as yet another new species,Diatryma steini.[10]

After the description ofDiatryma,most new European specimens were referred to this genus, instead ofGastornis;however, after the initial discovery ofDiatryma,it soon became clear that it (andGastornis) were so similar that the former could be considered ajunior synonymof the latter. In fact, this similarity was recognized as early as1884byElliott Coues,though this would be debated by researchers throughout the 20th century. Meaningful comparisons betweenGastornisandDiatrymawere made more difficult by Lemoine's incorrect skeletal illustration, the composite nature of which was not discovered until the early1980s.Following this, several authors began to recognize a greater degree of similarity between the European and North American birds, often placing both in the same order (†Gastornithiformes) or even family (†Gastornithidae). This newly-realized degree of similarity caused many scientists to, tentatively, accept the animals' synonymy—pending a comprehensive review of the anatomy of the birds.[3]Consequently, the correct scientific name of the genus isGastornis.[11]

Description

Gastornisis known from a large amount of fossil remains, but the clearest picture of the bird comes from a few nearly complete specimens of the speciesG. gigantea.These were generally very large birds, with huge beaks and massive skulls superficially similar to the carnivorous South American "terror birds" (phorusrhacids). The largest known species,G. giganteacould reached about 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in maximum height,[12]and up to 175 kg (386 lb) in mass.[13]

The skull ofG. giganteawas huge compared to the body and powerfully built. The beak was extremely tall and compressed (flattened from side to side). Unlike other species ofGastornis,G. gigantealacked characteristic grooves and pits on the underlying bone. The 'lip' of the beak was straight, without a raptorial hook as found in the predatory phorusrhacids. The nostrils were small and positioned close to the front of the eyes about midway up the skull. The vertebrae were short and massive, even in the neck. The neck was relatively short, consisting of at least 13 massive vertebrae. The torso was relatively short. The wings were vestigial, with the upper wing-bones small and highly reduced, similar in proportion to the wings of thecassowary.[10]

Classification

Gastornisand its close relatives are classified together in thefamilyGastornithidae,and were long considered to be members of the orderGruiformes.However, the traditional concept of Gruiformes has since been shown to be anunnatural grouping.Beginning in the late 1980s with the firstphylogeneticanalysis of gastornithid relationships, consensus began to grow that they were close relatives of the lineage that includeswaterfowlandscreamers,theAnseriformes.[14]A 2007 study showed that gastornithids were a very early-branching group of anseriformes, and formed the sister group to all other members of that lineage.[15]

Recognizing the apparent close relationship between gastornithids and waterfowl, some researchers classify gastornithids within the anseriform group itself.[15]Others restrict the name Anseriformes only to thecrown groupformed by all modern species, and label the larger group including extinct relatives of anseriformes, like the gastornithids, with the nameAnserimorphae.[16]Gastornithids are therefore sometimes placed in their ownorder,Gastornithiformes.[17]A 2024 study however found little support for Gastornithiformes and instead placesGastornisas a member of the Galliformescrown group,as more closely related toPhasianoideathan tomegapodes,being sister to the extinctSylviornithidae,a recently extinct group of medium-sized flightless birds known from subfossil deposits in the Western Pacific.[18]

A simplified version of the family tree found by Agnolinet al.in 2007 is reproduced below.

| Anseriformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Today, at least five species ofGastornisare generally accepted as valid. Thetype species,Gastornis parisiensis,was named and described by Hébert in two 1855 papers.[19][20]It is known from fossils found in western and central Europe, dating from the late Paleocene to the early Eocene. Other species previously considered distinct, but which are now considered synonymous withG. parisiensis,includeG. edwardsii(Lemoine, 1878) andG. klaasseni(Newton, 1885). Additional European species ofGastornisareG. russeli(Martin,1992) from the late Paleocene ofBerru, France,andG. sarasini(Schaub, 1929) from the early-middle Eocene.G. geiselensis,from the middle Eocene ofMessel,Germany, has been considered a synonym ofG. sarasini,[11]however, other researchers have stated that there is currently insufficient evidence to synonymize the two, and that they should be kept separate at least pending a more detailed comparison of all gastornithids.[21]The supposed small speciesG. minoris considered to be anomen dubium.[3]

Gastornis gigantea(Cope,1876), formerlyDiatryma,dates from the middle Eocene of western North America. Its junior synonyms includeBarornis regens(Marsh,1894) andOmorhamphus storchii(Sinclair, 1928).O. storchiiwas described based on fossils from lowerEocenerocks ofWyoming.[22]The species was named in honor of T. C. von Storch, who found the fossils remains in Princeton 1927 Expedition.[23]The fossil bones originally described asOmorhamphus storchiiare now considered to be the remains of a juvenileGastornis gigantea.[24]SpecimenYPMPU13258 from lower EoceneWillwood Formationrocks ofPark County, Wyomingalso seems to be a juvenile – perhaps also ofG. gigantea,in which case it would be an even younger individual.[25]

Gastornis xichuanensis,from the early Eocene ofHenan,China, is known only from a tibiotarsus (upper foot bone). It was originally described in 1980 as the only species in the distinct genusZhongyuanus.[26]However, a re-evaluation of the fossil published in 2013 concluded that the differences between this specimen and the same bone inGastornisspecies were minor, and that it should be considered an asian species ofGastornis.[27]

Paleobiology

Diet

A long-standing debate surroundingGastornisis the interpretation of its diet. It has often been depicted as a predator of contemporary small mammals, which famously included the early horseEohippus.[10]However, with the size ofGastornislegs, the bird would have had to have been more agile to catch fast-moving prey than the fossils suggest it to have been. Consequently,Gastornishas been suspected to have been an ambush hunter and/or used pack hunting techniques to pursue or ambush prey; ifGastorniswas a predator, it would have certainly needed some other means of hunting prey through the dense forest. Alternatively, it could have used its strong beak for eating large or strong vegetation.

The skull ofGastornisis massive in comparison to those of livingratitesof similar body size.Biomechanicalanalysis of the skull suggests that the jaw-closing musculature was enormous. The lower jaw is very deep, resulting in a lengthened moment arm of the jaw muscles. Both features strongly suggest thatGastorniscould generate a powerful bite.[12]Some scientists have proposed that the skull ofGastorniswas ‘overbuilt’ for a herbivorous diet and support the traditional interpretation ofGastornisas a carnivore that used its powerfully constructed beak to subdue struggling prey and crack open bones to extract marrow.[12]Others have noted the apparent lack of predatory features in the skull, such as a prominently hooked beak, as evidence thatGastorniswas a specialized herbivore (or even anomnivore) of some sort, perhaps having used its large beak to crack hard foods like nuts and seeds.[28]Footprints attributed to gastornithids (possibly a species ofGastornisitself), described in 2012, showed that these birds lacked strongly hooked talons on the hind legs, another line of evidence suggesting that they did not have a predatory lifestyle.[29]

Recent evidence suggests thatGastorniswas likely a true herbivore.[13]Studies of the calcium isotopes in the bones of specimens ofGastornisby Thomas Tutken and colleagues showed no evidence that it had meat in its diet. The geochemical analysis further revealed that its dietary habits were similar to those of both herbivorous dinosaurs and mammals when it was compared to known fossil carnivores, such asTyrannosaurus rex,leavingphorusrhacidsandbathornithidsas the only major carnivorous flightless birds.[30]

Eggs

InLate Paleocenedeposits of Spain and earlyEocenedeposits of France, shell fragments of hugeeggshave turned up, namely inProvence.[31][32]These were described as theootaxonOrnitholithusand are presumably fromGastornis.While no direct association exists betweenOrnitholithusandGastornisfossils, no other birds of sufficient size are known from that time and place; while the largeDiogenornisandEremopezusare known from the Eocene, the former lived in South America (still separated from North America by theTethys Oceanthen) and the latter is only known from the Late Eocene of North Africa, which also was separated by an (albeit less wide) stretch of the Tethys Ocean from Europe.[33]

Some of these fragments were complete enough to reconstruct a size of 24 by 10 cm (about 9.5 by 4 inches) with shells 2.3–2.5 mm (0.09–0.1 in) thick,[31]roughly half again as large as an ostrich egg and very different in shape from the more rounded ratite eggs. IfRemiornisis indeed correctly identified as a ratite (which is quite doubtful, however[11]),Gastornisremains as the only known animal that could have laid these eggs. At least one species ofRemiornisis known to have been smaller thanGastornis,and was initially described asGastornis minorby Mlíkovský in 2002. This would nicely match the remains of eggs a bit smaller than those of the living ostrich, which have also been found inPaleogenedeposits of Provence, were it not for the fact that these eggshell fossils also date from the Eocene, but noRemiornisbones are yet known from that time.[32]

Footprints

Several sets of fossil footprints are suspected to belong toGastornis.One set of footprints was reported from lateEocenegypsumatMontmorencyand other locations of theParis Basinin the 19th century, from 1859 onwards. Described initially byJules Desnoyers,and later on byAlphonse Milne-Edwards,these trace fossils were celebrated among French geologists of the late 19th century. They were discussed byCharles Lyellin hisElements of Geologyas an example of the incompleteness of the fossil record – no bones had been found associated with the footprints.[34]Unfortunately, these fine specimens, which sometimes even preserved details of the skin structure, are now lost. They were brought to theMuséum national d'histoire naturellewhen Desnoyers started to work there, and the last documented record of them deals with their presence in the geology exhibition of the MNHN in 1912. The largest of these footprints, although only consisting of a single toe's impression, was 40 cm (16 in) long. The large footprints from theParis Basincould also be divided into huge and merely large examples, much like the eggshells from southern France, which are 20 million years older.[33]

Another footprint record consists of a single imprint that still exists, though it has proven to be even more controversial. It was found in late EocenePuget Grouprocks in theGreen Rivervalley nearBlack Diamond, Washington.After its discovery, it raised considerable interest in theSeattlearea in May–July 1992, being subject of at least two longer articles in theSeattle Times.[35][36]Variously declared ahoaxor genuine, this apparent impression of a single bird foot measures about 27 cm (11 in) wide by 32 cm (13 in) long and lacks ahallux(hind toe); it was described as theichnotaxonOrnithoformipes controversus.Fourteen years after the initial discovery, the debate about the find's authenticity was still unresolved.[37]The specimen is now atWestern Washington University.[38][39]

The problem with these early trace fossils is that no fossil ofGastornishas been found to be younger than about 45 million years. The Enigma tic"Diatryma" coteiis known from remains almost as old as the Paris basin footprints (whose date never could be accurately determined), but in North America the fossil record of unequivocal gastornithids seems to end even earlier than in Europe.[33][39]However, in 2009, a landslide nearBellingham, Washingtonexposed at least 18 tracks on 15 blocks in the EoceneChuckanut Formation.The anatomy and age (about 53.7 Ma old[40]) of the tracks suggest that the track maker wasGastornis.Although these birds have long been considered to be predators or scavengers, the absence of raptor-like claws supports earlier suggestions that they were herbivores. The Chuckanut tracks are named as the ichnotaxonRivavipes giganteus,inferred to belong to the extinct family Gastornithidae. At least 10 of the tracks are on display at Western Washington University.[41]

Feathers

TheplumageofGastornishas generally been depicted in art as a hair-like covering similar to someratites.This has been based in part on some fibrous strands recovered from aGreen River Formationdeposit atRoan Creek, Colorado,which were initially believed to representGastornisfeathers and namedDiatryma? filifera.[42]Subsequent examination has shown the fossil material to not actually be feathers,[43]butroot fibersand the species renamed asCyperacites filiferus.[44]

A second possibleGastornisfeather has since been identified, also from the Green River Formation. Unlike the filamentous plant material, this single isolated feather resembles the body feathers of flighted birds, being broad and vaned. It was tentatively identified as a possibleGastornisfeather based on its size; the feather measured 240 mm (9.4 in) long and must have belonged to a gigantic bird.[45][46]

Distribution

Gastornisfossils are known from across western Europe, the western United States, and central China. The earliest (Paleocene) fossils all come from Europe, and it is likely that the genus originated there. Europe in this epoch was an island continent, andGastorniswas the largest terrestrial tetrapod of the landmass. This offers parallels with the Malagasyelephant birds,herbivorous birds that were similarly the largest land animals in the isolated landmass ofMadagascar,in spite of otherwise mammalian megafauna.[47]

All other fossil remains are from the Eocene; however, it is not currently known howGastornisdispersed out of Europe and into North America and Asia. Given the presence ofGastornisfossils in the early Eocene of western China, these birds may have spread east from Europe and crossed into North America via theBering land bridge.Gastornisalso may have spread both east and west, arriving separately in eastern Asia and in North America across theTurgai Strait.[27]Direct landbridges with North America are also known.[47]

EuropeanGastornissurvived somewhat longer than their North American and Asian counterparts. This seems to coincide with a period of increased isolation of the continent.[47]

Extinction

The reason for the extinction ofGastornisis currently unclear. Competition with mammals has often been cited as a possible factor, butGastornisdid occur in faunas dominated by mammals, and did co-exist with several megafaunal forms likepantodonts.[47]Likewise, extreme climatic events like thePaleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM)appear to have had little impact.[47]

Nonetheless, the extended survival in Europe is thought to coincide with increased isolation of the landmass.[47]

References

- ^Cécile Mourer-Chauviré; Estelle Bourdon (2020)."Description of a new species ofGastornis(Aves, Gastornithiformes) from the early Eocene of La Borie, southwestern France "(PDF).Geobios.63:39–46.Bibcode:2020Geobi..63...39M.doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2020.10.002.S2CID228975095.

- ^Prévost, Constant (1855)."Annonce de la découverte d'un oiseau fossile de taille gigantesque, trouvé à la partie inférieure de l'argile plastique des terrains parisiens [" Announcement of the discovery of a fossil bird of gigantic size, found in the lower Argile Plastique formation of the Paris region "]".C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris(in French).40:554–557.

- ^abcBuffetaut, E., and Burrrraur, E. (1997). "New remains of the giant birdGastornisfrom the Upper Paleocene of the eastern Paris Basin and the relationships betweenGastornisandDiatryma."N. Jb. Geol. Palâont. Mh.,(3): 179–190.[1][dead link]

- ^Martin L.D. (1992). "The status of the Late Paleocene birdsGastornisandRemiornis".Papers in Avian Paleontology Honoring Pierce Brodkorb. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series.36:97–108.

- ^Lemoine, V. (1881a).Recherches sur les oiseaux fossiles des terrains tertiaires inférieurs des environs de Reims.Vol. 2. Matot-Braine, Reims. pp. 75–170.

- ^Lemoine, V. (1881b)."Sur leGastornis Edwardsiiet leRemiornis Hebertide l'éocène inférieur des environs de Reims [ "OnG. edwardsiiandR. hebertifrom the Lower Eocene of the Reims area "]".C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris(in French).93:1157–1159.

- ^The biologist's handbook of pronunciations(1960)

- ^Cope, Edward Drinker (1876). "On a gigantic bird from the Eocene of New Mexico".Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.28(2): 10–11.

- ^Feduccia, Alan (1999).The Origin and Evolution of Birds(2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN0300078617.

- ^abcdefMatthew W.D.; Granger W.; Stein W. (1917). "The skeleton ofDiatryma,a gigantic bird from the Lower Eocene of Wyoming ".Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.37(11): 307–354.

- ^abcMlíkovský, Jirí (2002).Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe(PDF).Prague: Ninox Press. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 20 May 2011.Retrieved21 April2008.

- ^abcWitmer, Lawrence; Rose, Kenneth (1991)."Biomechanics of the jaw apparatus of the gigantic Eocene birdDiatryma:Implications for diet and mode of life "(PDF).Paleobiology.17(2): 95–120.Bibcode:1991Pbio...17...95W.doi:10.1017/S0094837300010435.S2CID18212799.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 July 2010.

- ^abAngst D.; Lécuyer C.; Amiot R.; Buffetaut E.; Fourel F.; Martineau F.; Legendre S.; Abourachid A.; Herrel A. (2014). "Isotopic and anatomical evidence of an herbivorous diet in the Early Tertiary giant bird Gastornis. Implications for the structure of Paleocene terrestrial ecosystems".Naturwissenschaften.101(4): 313–322.Bibcode:2014NW....101..313A.doi:10.1007/s00114-014-1158-2.PMID24563098.S2CID18518649.

- ^Mustoe G.E.; Tucker D.S.; Kemplin K.L. (2012)."Giant Eocene bird footprints from northwest Washington, USA".Palaeontology.55(6): 1293–1305.Bibcode:2012Palgy..55.1293M.doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01195.x.

- ^abAgnolin, F. (2007). "Brontornis burmeisteriMoreno & Mercerat, un Anseriformes (Aves) gigante del Mioceno Medio de Patagonia, Argentina. "Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales,n.s. 9, 15–25

- ^Andors A.V. (1992). "Reappraisal of the Eocene ground birdDiatryma(Aves: Anserimorphae) ".Science Series Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.36:109–125.

- ^Buffetaut, E. (2002). "Giant ground birds at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary: Extinction or survival?"Special papers – Geological Society of America,303–306.

- ^McInerney, Phoebe L.; Blokland, Jacob C.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2 June 2024). [10.1080/08912963.2024.2308212 "Skull morphology of the Enigma tic Genyornis newtoni Stirling and Zeitz, 1896 (Aves, Dromornithidae), with implications for functional morphology, ecology, and evolution in the context of Galloanserae" ].Historical Biology.36(6): 1093–1165.doi:10.1080/08912963.2024.2308212.ISSN0891-2963.

{{cite journal}}:Check|url=value (help) - ^Hébert, E. (1855a)."Note sur le tibia duGastornis pariensis [sic][ "Note on the tibia ofG. parisiensis"]".C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris(in French).40:579–582.

- ^Hébert, E. (1855b)."Note sur le fémur duGastornis parisiensis[ "Note on the femur ofG. parisiensis"]".C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris(in French).40:1214–1217.

- ^Hellmund M (2013). "Reappraisal of the bone inventory ofGastornis geiselensis(Fischer, 1978) from the Eocene Geiseltal Fossillagerstatte (Saxony-Anhalt, Germany) ".Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen.269(2): 203–220.doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2013/0345.

- ^Sinclair, W. J. (1928). "Omorhamphus,a New Flightless Bird from the Lower Eocene of Wyoming ".Proc. Am. Philos. Soc.LXVII(1): 51–65.JSTOR984256.

- ^"Recent Literature"(PDF).The Auk.45(4): 522–523. 1928.doi:10.2307/4075674.JSTOR4075674.

- ^Brodkorb, Pierce (1967)."Catalogue of Fossil Birds: Part 3 (Ralliformes, Ichthyornithiformes, Charadriiformes)".Bulletin of the Florida State Museum.11(3). Archived fromthe originalon 23 February 2008.Retrieved21 April2008.

- ^Wetmore, Alexander (1933)."Fossil Bird Remains from the Eocene of Wyoming"(PDF).Condor.35(3): 115–118.doi:10.2307/1363436.JSTOR1363436.

- ^Hou L (1980). "New form of the Gastornithidae from the Lower Eocene of the Xichuan, Honan".Vertebrata PalAsiatica.18:111–115.

- ^abBuffetaut E (2013). "The giant birdGastornisin Asia: A revision ofZhongyuanus xichuanensisHou, 1980, from the Early Eocene of China ".Paleontological Journal.47(11): 1302–1307.Bibcode:2013PalJ...47.1302B.doi:10.1134/s0031030113110051.S2CID84611178.

- ^Andors, Allison (1992). "Reappraisal of the Eocene groundbirdDiatryma(Aves: Anserimorphae) ".Papers in Avian Paleontology Honoring Pierce Brodkorb–Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series.36:109–125.

- ^Mustoe, George E; Tucker David S; Kemplin, Keith L (2012)."Giant Eocene Bird Footprints From Northwest Washington, USA".Palaeontology.55(6): 1293–1305.Bibcode:2012Palgy..55.1293M.doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01195.x.

- ^"Terror bird's beak was worse than its bite: 'Terror bird' was probably a herbivore".Sciencedaily. 29 August 2013.Retrieved10 September2013.

- ^abDughi, R.; Sirugue, F. (1959)."Sur des fragments de coquilles d'oeufs fossiles de l'Eocène de Basse-Provence [" On fossil eggshell fragments from the Eocene of Basse-Provence "]".C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris(in French).249:959–961.

- ^abFabre-Taxy, Suzanne; Touraine, Fernand (1960)."Gisements d'œufs d'Oiseaux de très grande taille dans l'Eocène de Provence [" Deposits of eggs from birds of very large size from the Eocene of Provence "]".C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris(in French).250(23): 3870–3871.

- ^abcBuffetaut, Eric (2004). "Footprints of Giant Birds from the Upper Eocene of the Paris Basin: An Ichnological Enigma".Ichnos.11(3–4): 357–362.Bibcode:2004Ichno..11..357B.doi:10.1080/10420940490442287.

- ^Lyell, Charles (1865).Elements of Geology(6th ed.). J. Murray.

- ^Dietrich, B. (3 May 1992)."'Big Bird' Footprint Has Scientists Aflutter – If Proven, Fossil Find Would Be A State First ".Seattle Times.p. B1–2.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^Dietrich, B. (17 July 1992)."Track Is Hoax, Paleontologists Say – Expert On Prehistoric Bird Casts Doubt On Discovery In State Park".Seattle Times.p. B4.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^Doughton, Sandi (6 December 2004)."Big birds on the Green River? The debate continues".Seattle Times.

- ^Bigelow, Phil (2 April 2006)."Controversial Patterson" Diatryma footprint "slab has been moved".Dinosaur Mailing List.Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.Retrieved21 April2008.

- ^abPatterson, John; Lockley, Martin (2004). "A ProbableDiatrymaTrack from the Eocene of Washington: An Intriguing Case of Controversy and Skepticism ".Ichnos.11(3–4): 341–347.Bibcode:2004Ichno..11..341P.doi:10.1080/10420940490442278.

- ^Breedlovestrout, R. (2011).Paleofloristic Studies in the Paleogene Chuckanut Basin, Western Washington, USA.Unpublished Phd Dissertation(Thesis). University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho.

- ^Mustoe, G. E.; Tucker, D. S.; Kemplin, K. L. (2012)."Giant Eocene bird footprints from northwest Washington, USA".Palaeontology.55(6): 1293–1305.Bibcode:2012Palgy..55.1293M.doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01195.x.

- ^Cockerell, Theodore Dru Alison (1923)."The Supposed Plumage of the Eocene BirdDiatryma"(PDF).American Museum Novitates(62): 1–4.

- ^Wetmore, Alexander(1930)."The Supposed Plumage of the Eocene Diatryma"(PDF).Auk.47(4): 579–580.doi:10.2307/4075897.JSTOR4075897.

- ^Becker, H. F. (1962). "Reassignment ofEopuntiatoCyperacites".Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club.89(5): 319–330.doi:10.2307/2482937.JSTOR2482937.

- ^Grande, L. (2013).The Lost World of Fossil Lake: Snapshots from Deep Time.University of Chicago Press.

- ^"Fossilized Feathers | Zoology, Division of Birds".birds.fieldmuseum.org.Retrieved22 February2020.

- ^abcdefBuffetaut Eric, Angst Delphine (2014). "Stratigraphic distribution of large flightless birds in the Palaeogene of Europe and its palaeobiological and palaeogeographical implications".Earth-Science Reviews.138:394–408.Bibcode:2014ESRv..138..394B.doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2014.07.001.

External links

- "The unfinished story of the Early Tertiary giant bird Gastornis".Geological Society of Denmark. Archived fromthe originalon 28 September 2007.Retrieved11 April2008.