Gastrotrich

| Gastrotrich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Darkfield photograph of a gastrotrich | |

| |

| SEM photomicrograph ofThaumastodermaramuliferum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia |

| Clade: | Rouphozoa |

| Phylum: | Gastrotricha Metschnikoff, 1865[1] |

| Orders | |

Thegastrotrichs(phylumGastrotricha),commonlyreferred to ashairybelliesorhairybacks,are a group ofmicroscopic(0.06–3.0 mm), cylindrical,acoelomateanimals,and are widely distributed and abundant infreshwaterandmarineenvironments. They are mostlybenthicand live within theperiphyton,the layer of tinyorganismsanddetritusthat is found on theseabedand the beds of otherwater bodies.The majority live on and between particles ofsedimentor on other submerged surfaces, but a few species are terrestrial and live on land in the film of water surrounding grains ofsoil.Gastrotrichs are divided into twoorders,theMacrodasyidawhich are marine (except for two species), and theChaetonotida,some of which are marine and some freshwater. Nearly 800 species of gastrotrich have been described.

Gastrotrichs have a simple body plan with a head region, with abrainandsensory organs,and a trunk with a simple gut and thereproductive organs.They have adhesive glands with which they can anchor themselves to thesubstrateandciliawith which they move around. They feed on detritus, sucking up organic particles with their muscularpharynx.They arehermaphrodites,the marine species producing eggs which develop directly into miniatureadults.The freshwater species areparthenogenetic,producing unfertilised eggs, and at least one species isviviparous.Gastrotrichs mature with great rapidity and have lifespans of only a few days.

Etymology and taxonomy

[edit]The name "gastrotrich" comes from theGreekγαστήρgaster,meaning "stomach", and θρίξthrix,meaning "hair".[2]The name was coined by the Russian zoologistÉlie Metchnikoffin 1865.[1]The common name "hairyback" apparently arises from a mistranslation of "gastrotrich".[3]

The relationship of gastrotrichs to other phyla is unclear.Morphologysuggests that they are close to theGnathostomulida,theRotifera,or theNematoda.On the other hand,genetic studiesplace them as close relatives of thePlatyhelminthes,theEcdysozoaor theLophotrochozoa.[4]As of 2011, around 790 species have been described.[5]The phylum contains a single class, divided into two orders: theMacrodasyidaand theChaetonotida.[6]Edward Ruppertet al.report that the Macrodasyida are wholly marine,[6]but two rare and poorly known species,Marinellina flagellataandRedudasys fornerise,are known from fresh water.[7]The Chaetonotida comprises both marine and freshwater species.[6]

Anatomy

[edit]

Gastrotrichs vary in size from about 0.06 to 3 mm (0.002 to 0.118 in) in body length.[4]They arebilaterally symmetrical,with a transparent strap-shaped orbowling pin-shaped body, arched dorsally and flattened ventrally. Theanteriorend is not clearly defined as a head but contains the sense organs, brain and pharynx.Ciliaare found around the mouth and on the ventral surface of the head and body. The trunk contains the gut and the reproductive organs. At theposteriorend of the body are two projections with cement glands that serve in adhesion. This is a double-gland system where one gland secretes the glue and another secretes a de-adhesive agent to sever the connection. In the Macrodasyida, there are additional adhesive glands at the anterior end and on the sides of the body.[6]

The body wall consists of acuticle,anepidermisand longitudinal and circular bands of muscle fibres. In someprimitivespecies, each epidermal cell has a single cilium, a feature shared only by thegnathostomulans.The whole ventral surface of the animal may be ciliated or the cilia may be arranged in rows, patches or transverse bands. The cuticle is locally thickened in some gastrotrichs and forms scales, hooks and spines. There is nocoelom(body cavity) and the interior of the animal is filled with poorly differentiatedconnective tissue.In the macrodasyidans, Y-shaped cells, each containing avacuole,surround the gut and may function as ahydrostatic skeleton.[6]

The mouth is at the anterior end and opens into an elongated muscularpharynxwith a triangular or Y-shapedlumen,lined bymyoepithelial cells.The pharynx opens into a cylindrical intestine, which is lined with glandular and digestive cells. Theanusis located on the ventral surface close to the posterior of the body. In some species, there are pores in the pharynx opening to the ventral surface; these contain valves and may allowegestionof any excess water swallowed while feeding.[6]

In the chaetonotidans, the excretory system consists of a single pair ofprotonephridia,which open through separate pores on the lateral underside of the animal, usually in the midsection of the body. In the macrodasyidans, there are several pairs of these opening along the side of the body.Nitrogenous wasteis probably excreted through the body wall, as part of respiration, and the protonephridia are believed to function mainly inosmoregulation.[6]Unusually, the protonephridia do not take the form offlame cells,but, instead, the excretory cells consist of a skirt surrounding a series ofcytoplasmicrods that in turn enclose a centralflagellum.These cells, termedcyrtocytes,connect to a single outlet cell which passes the excreted material into the protonephridial duct.[8]

As is typical for such small animals, there are no respiratory or circulatory organs. The nervous system is relatively simple. The brain consists of twoganglia,one on either side of the pharynx, connected by acommissure.From these lead a pair of nerve cords which run along either side of the body beside the longitudinal muscle bands. The primary sensory organs are the bristles and ciliated tufts of the body surface which function asmechanoreceptors.There are also ciliated pits on the head, simple ciliaryphotoreceptorsand fleshy appendages which act aschemoreceptors.[6]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

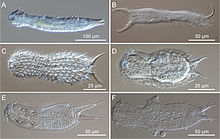

C, D, E & F = Chaetonotida

Gastrotrichs arecosmopolitanin distribution. They inhabit the interstitial spaces between particles in marine and freshwater environments, the surfaces of aquatic plants and other submerged objects and the surface film of water surrounding soil particles on land.[4]They are also found in stagnant pools and anaerobic mud, where they thrive even in the presence ofhydrogen sulfide.When pools dry up they can survive periods of desiccation as eggs, and some species are capable of formingcystsin harsh conditions.[9]In marine sediments they have been known to reach 364 individuals per 10 cm2(1.6 sq in) making them the third most common invertebrate in the sediment afternematodesandharpacticoid copepods.In freshwater they may reach a density of 158 individuals per 10 cm2(1.6 sq in) and are the fifth most abundant group of invertebrates in the sediment.[4]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]In marine and freshwater environments, gastrotrichs form part of thebenthic community.They aredetritivoresand are microphagous: they feed by sucking small dead or living organic materials,diatoms,bacteriaand small protozoa into their mouths by the muscular action of the pharynx. They are themselves eaten byturbellariansand other smallmacrofauna.[4]

Like many microscopic animals, gastrotrich locomotion is primarily powered byhydrostatics,but movement occurs through different methods in different members of the group. Chaetonotids only have adhesive glands at the back and, in them, locomotion typically proceeds in a smooth gliding manner; the whole body is propelled forward by the rhythmic action of the cilia on the ventral surface. In thepelagicchaetonotid genusStylochaeta,however, movement proceeds in jerks as the long, muscle-activated spines are forced rhythmically towards the side of the body. By contrast, with chaetonotids, macrodasyidans typically have multiple adhesive glands and move forward with a creeping action similar to that of a"looper" caterpillar.In response to a threat, the head and trunk can be rapidly pulled backwards, or the creeping movement can be reversed. Muscular action is important when the animal turns sideways and during copulation, when two individuals twine around each other.[6]

Reproduction and lifespan

[edit]

Gastrotrich reproduction and reproductive behaviour has been little studied. That ofmacrodasiydsprobably most represents that of the ancestral lineage and these more primitive gastrotrichs are simultaneoushermaphrodites,possessing both male and female sex organs. There is generally a single pair ofgonads,the anterior portion of which containssperm-producing cells and the posterior portion producingova.The sperm is sometimes packaged inspermatophoresand is released through malegonoporesthat open, often temporarily, on the underside of the animal, roughly two-thirds of the way along the body. Acopulatory organon the tail collects the sperm and transfers it to the partner'sseminal receptaclethrough the female gonopore. Details of the process and the behaviour involved vary with the species, and there is a range of different accessory reproductive organs. During copulation, the "male" individual uses his copulatory organ to transfer sperm to his partner's gonopore and fertilisation is internal. The fertilised eggs are released by rupture of the body wall which afterwards repairs itself. As is the case in mostprotostomes,development of the embryo isdeterminate,with each cell destined to become a specific part of the animal's body.[6]At least one species of gastrotrich,Urodasys viviparus,isviviparous.[10]

Many species of chaetotonid gastrotrichs reproduce entirely byparthenogenesis.In these species, the male portions of the reproductive system are degenerate and non-functional, or, in many cases, entirely absent. Though the eggs have a diameter of less than 50μm,they are still very large in comparison with the animals' size. Some species are capable of laying eggs that remaindormantduring times ofdesiccationor low temperatures; these species, however, are also able to produce regular eggs, which hatch in one to four days, when environmental conditions are more favourable. The eggs of all gastrotrichs undergodirect developmentand hatch into miniature versions of the adult. The young typically reach sexual maturity in about three days. In the laboratory,Lepidodermella squamatumhas lived for up to forty days, producing four or five eggs during the first ten days of life.[6]

Gastrotrichs demonstrateeutely,each species having an invariant genetically fixed number of cells as adults. Cell division ceases at the end of embryonic development and further growth is solely due to cell enlargement.[6]

Classification

[edit]Gastrotricha is divided into two orders and a number of families:[1][4]

|

OrderMacrodasyidaRemane, 1925 [Rao and Clausen, 1970]

|

OrderChaetonotidaRemane, 1925 [Rao and Clausen, 1970] SuborderMultitubulatinad'Hondt, 1971

SuborderPaucitubulatinad'Hondt, 1971

|

References

[edit]- ^abcTodaro, Antonio (2013)."Gastrotricha".WoRMS.World Register of Marine Species.Retrieved2014-01-26.

- ^"Gastrotrich".The Free Dictionary.Retrieved2014-01-29.

- ^Marren, Peter(2010).Hairybacks Gastrotricha: Bugs Britannica.Random House. p. 27.ISBN978-0-7011-8180-2.

- ^abcdefTodaro, M. A. (2014-01-03)."Gastrotricha".Retrieved2014-01-23.

- ^Zhang, Z.-Q. (2011)."Animal biodiversity: An introduction to higher-level classification and taxonomic richness"(PDF).Zootaxa.3148:7–12.doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.3.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^abcdefghijklRuppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004).Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition.Cengage Learning. pp. 753–757.ISBN978-81-315-0104-7.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Todaro, M. A.; Dal Zotto, M.; Jondelius, U.; Hochberg, R.; Hummon, W. D.; Kånneby, T.; Rocha, C. E. F. (14 February 2012)."Gastrotricha: A Marine Sister for a Freshwater Puzzle".PLOS ONE.7(2): e31740.Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731740T.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031740.PMC3279426.PMID22348127.

- ^Barnes, Robert D. (1982).Invertebrate Zoology.Holt-Saunders International. pp. 263–272.ISBN0-03-056747-5.

- ^Adl, Sina M. (2003).The Ecology of Soil Decomposition: Gastrotrichs.CABI. p. 52.ISBN978-0-85199-661-5.

- ^Elena, Fregni; Faienza, Maria Grazia; De Zio Grimaldi, Susanna; Tongiorgi, Paolo; Balsamo, Maria (1999)."Marine gastrotrichs from the Tremiti archipelago in the southern Adriatic Sea, with the description of two new species ofUrodasys".Italian Journal of Zoology.66(2): 183–194.doi:10.1080/11250009909356254.