Gdańsk

Gdańsk | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): Nec temere, nec timide (Neither rashly, nor timidly) | |

| |

| Coordinates:54°20′51″N18°38′43″E/ 54.34750°N 18.64528°E | |

| Country | Poland |

| Voivodeship | Pomeranian |

| County | city county |

| Established | 10th century |

| City rights | 1263 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Gdańsk City Council |

| •City mayor | Aleksandra Dulkiewicz(Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • City | 266 km2(103 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 414.81 km2(160.16 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 180 m (590 ft) |

| Population (30 June 2023) | |

| • City | 486,492 (6th)[1] |

| • Density | 1,800/km2(5,000/sq mi) |

| •Urban | 749,786 |

| •Metro | 1,080,700 |

| GDP | |

| • Urban | €20.529 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Postal code | 80-008 to 80–958 |

| Area code | +48 58 |

| Car plates | GD |

| Website | gdansk.pl |

Gdańsk[a]is a city on theBalticcoast of northernPoland,and the capital of thePomeranian Voivodeship.With a population of 486,492,[8]it is Poland's sixth-largest city and principalseaport.[9][7]Gdańsk lies at the mouth of theMotławaRiver and is situated at the southern edge ofGdańsk Bay,close to the city ofGdyniaandresort townofSopot;these form ametropolitan areacalled theTricity(Trójmiasto), with a population of approximately 1.5 million.[10]

The city has a complex history, having had periods of Polish, German and self rule. An important shipbuilding and trade port since theMiddle Ages,in 1361 it became a member of theHanseatic Leaguewhich influenced its economic, demographic andurban landscape.It also served as Poland's principal seaport, and was the largest city of Poland in the 15th-17th centuries. In 1793, within thePartitions of Poland,the city became part ofPrussia,and thus a part of theGerman Empirefrom 1871 after theunification of Germany.FollowingWorld War Iand theTreaty of Versailles,it was aFree Cityunder the protection of theLeague of Nationsfrom 1920 to 1939. On 1 September 1939 it was the scene of thefirst clashofWorld War IIatWesterplatte.The contemporary city was shaped by extensiveborder changes,expulsionsandnew settlementafter 1945. In the 1980s, Gdańsk was the birthplace of theSolidaritymovement, which helped precipitate the collapse of theEastern Bloc,thefall of the Berlin Walland the dissolution of theWarsaw Pact.

Gdańsk is home to theUniversity of Gdańsk,Gdańsk University of Technology,theNational Museum,theGdańsk Shakespeare Theatre,theMuseum of the Second World War,thePolish Baltic Philharmonic,thePolish Space Agencyand theEuropean Solidarity Centre.Among Gdańsk's most notable historical landmarks are theTown Hall,theGreen Gate,Artus Court,Neptune's Fountain,andSt. Mary's Church,one of the largest brick churches in the world. The city is served byGdańsk Lech Wałęsa Airport,the country'sthird busiest airportand the most important international airport in northern Poland.

Gdańsk is among the most visited cities in Poland, having received 3.4 million tourists according to data collected in 2019.[11]The city also hostsSt. Dominic's Fair,which dates back to 1260,[12]and is regarded as one of the biggest trade and cultural events in Europe.[13]Gdańsk has also topped rankings for the quality of life, safety and living standards worldwide, and its historic city centre has been listed as one of Poland'snational monuments.[14][15][16][17]

Names

[edit]Origin

[edit]

The name of the city was most likely derived fromGdania,a river presently known asMotławaon which the city is situated.[18]Other linguists also argue that the name stems from theProto-Slavicadjective/prefixgъd-,which meant 'wet' or 'moist' with the addition of themorphemeń/niand thesuffix-sk.[19]

History

[edit]The name of the settlement was recorded afterSt. Adalbert'sdeath in 997 CE asurbs Gyddanyzcand it was later written asKdanzkin 1148,Gdanzcin 1188,Danceke[20]in 1228,Gdańskin 1236,[b]Danzcin 1263,Danczkin 1311,[c]Danczikin 1399,[d]Danczigin 1414, andGdąnskin 1656.[21]

In Polish documents, the form Gdańsk was always used. The German form Danzig developed later, simplifying the consonant clusters to something easier for German speakers to pronounce.[22]The cluster "gd" became "d" (Danzcfrom 1263),[23]the combination "ns" became "nts" (Danczkfrom 1311).,[23]and finally anepenthetical"i" broke up the final cluster (Danczikfrom 1399).[23]

In Polish, the modern name of the city is pronounced[ɡdaj̃sk].In English (where thediacriticover the "n" is frequently omitted) the usual pronunciation is/ɡəˈdænsk/or/ɡəˈdɑːnsk/.The German name,Danzig,is usually pronounced[ˈdantsɪç],or alternatively[ˈdantsɪk]in more Southern German-speaking areas. The city'sLatinname may be given as eitherGedania,Gedanum,orDantiscum;the variety of Latin and German names typically reflects the difficulty of pronunciation of the Polish/Slavonic city's name, all German- and Latin/Romance-speaking populations always encounter in trying to pronounce the difficult and complex Polish/Slavonic words.

Ceremonial names

[edit]On special occasions, the city is also referred to as "The Royal Polish City of Gdańsk" (Polish:Królewskie Polskie Miasto Gdańsk,Latin:Regia Civitas Polonica Gedanensis,Kashubian:Królewsczi Pòlsczi Gard Gduńsk).[24][25][26]In theKashubian languagethe city is calledGduńsk.Although some Kashubians may also use the name "Our Capital City Gduńsk" (Nasz Stoleczny Gard Gduńsk) or "Our (regional) Capital City Gduńsk" (Stoleczny Kaszëbsczi Gard Gduńsk), the cultural and historical connections between the city and the region ofKashubiaare debatable and use of such names raises controversy among Kashubians.[27]

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]The oldest evidence found for the existence of a settlement on the lands of what is now Gdańsk comes from theBronze Age(which is estimated to be from 2500–1700 BCE). The settlement that is now known as Gdańsk began in the 9th century, being mostly anagricultureandfishing-dependent village.[28][29]In the beginning of the 10th century, it began becoming an important centre fortrade(especially between thePomeranians) until its annexation inc.975 byMieszko I.[30]

Early Poland

[edit]

The first written record thought to refer to Gdańsk is thevitaofSaint Adalbert.Written in 999, it describes how in 997 SaintAdalbert of Praguebaptised the inhabitants ofurbs Gyddannyzc,"which separated the great realm of the duke [i.e.,Bolesław the Braveof Poland] from the sea. "[32]No further written sources exist for the 10th and 11th centuries.[32]Based on the date in Adalbert'svita,the city celebrated its millennial anniversary in 1997.[33]

Archaeological evidence for the origins of the town was retrieved mostly afterWorld War IIhad laid 90percent of the city centre in ruins, enabling excavations.[34]The oldest seventeen settlement levels were dated to between 980 and 1308.[33]Mieszko I of Polanderected a stronghold on the site in the 980s, thereby connecting thePolish stateruled by thePiast dynastywith the trade routes of theBaltic Sea.[35]Traces of buildings and housing from the 10th century have been found in archaeological excavations of the city.[36]

Pomeranian Poland

[edit]

The site was ruled as aduchyof Poland by theSamborides.It consisted of a settlement at the modern Long Market, settlements of craftsmen along the Old Ditch, German merchant settlements around St Nicholas' Church and the old Piast stronghold.[37]In 1215, the ducal stronghold became the centre of aPomerelian splinter duchy.At that time the area of the later city included various villages.

In 1224/25, merchants fromLübeckwere invited ashospites(immigrants with specific privileges) but were soon (in 1238) forced to leave bySwietopelk IIof the Samborides during a war between Swietopelk and theTeutonic Knights,during which Lübeck supported the latter. Migration of merchants to the town resumed in 1257.[38]Significant German influence did not reappear until the 14th century, after the takeover of the city by the Teutonic Knights.[39]

At latest in 1263Pomerelianduke, Swietopelk II granted city rights underLübeck lawto the emerging market settlement.[40]It was anautonomy chartersimilar to that of Lübeck, which was also the primary origin of many settlers.[37]In a document of 1271 thePomereliandukeMestwin IIaddressed the Lübeck merchants settled in the city as his loyal citizens from Germany.[41][42]

In 1300, the town had an estimated population of 2,000. While overall the town was far from an important trade centre at that time, it had some relevance in the trade withEastern Europe.Low on funds, the Samborides lent the settlement to Brandenburg, although they planned to take the city back and give it to Poland. Poland threatened to intervene, and the Brandenburgians left the town. Subsequently, the city was taken by Danish princes in 1301.[43]

Teutonic Knights

[edit]

In 1308, the town was taken byBrandenburgand the Teutonic Knights restored order. Subsequently, the Knights took over control of the town. Primary sources record amassacrecarried out by the Teutonic Knights against the local population,[44]of 10,000 people, but the exact number killed is subject of dispute in modern scholarship.[45]Multiple authors accept the number given in the original sources,[46]while others consider 10,000 to have been a medieval exaggeration, although scholarly consensus is that a massacre of some magnitude did take place.[45]The events were used by the Polish crown to condemn the Teutonic Knights in a subsequent papal lawsuit.[45][47]

The knights colonized the area, replacing localKashubiansand Poles with German settlers.[46]In 1308, they foundedOsiek Hakelwerknear the town, initially as a Slavic fishing settlement.[44]In 1340, the Teutonic Knights constructed a large fortress, which became the seat of the knights'Komtur.[48]In 1346 they changed the Town Law of the city, which then consisted only of theRechtstadt,toKulm law.[49]In 1358, Danzig joined theHanseatic League,and became an active member in 1361.[50]It maintained relations with the trade centresBruges,Novgorod,Lisboa,andSevilla.[50]Around 1377, theOld Townwas equipped with city rights as well.[51]In 1380, theNew Townwas founded as the third, independent settlement.[44]

After a series ofPolish-Teutonic Wars,in theTreaty of Kalisz (1343)the Order had to acknowledge that it would hold Pomerelia as afieffrom thePolish Crown.Although it left the legal basis of the Order's possession of the province in some doubt, the city thrived as a result of increased exports of grain (especially wheat), timber,potash,tar, and other goods of forestry from Prussia and Poland via theVistulaRivertrading routes,although after its capture, the Teutonic Knights tried to actively reduce the economic significance of the town. While under the control ofthe Teutonic OrderGerman migration increased. The Order's religious networks helped to develop Danzig's literary culture.[52]A new war broke out in 1409, culminating in theBattle of Grunwald(1410), and the city came under the control of theKingdom of Poland.A year later, with theFirst Peace of Thorn,it returned to the Teutonic Order.[53]

Kingdom of Poland

[edit]

In 1440, the city participated in the foundation of thePrussian Confederationwhich was an organisation opposed to the rule of the Teutonic Knights. The organisation in its complaint of 1453 mentioned repeated cases in which the Teutonic Knights imprisoned or murdered local patricians and mayors without a court verdict.[54]On the request of the organisation KingCasimir IV of Polandreincorporated the territory to the Kingdom of Poland in 1454.[55]This led to theThirteen Years' Warbetween Poland and theState of the Teutonic Order(1454–1466). Since 1454, the city was authorized by the King to mint Polish coins.[56]The local mayor pledged allegiance to the King during the incorporation in March 1454 inKraków,[57]and the city again solemnly pledged allegiance to the King in June 1454 inElbląg,recognizing the prior Teutonic annexation and rule as unlawful.[58]On 25 May 1457 the city gained its rights as an autonomous city.[59]

On 15 May 1457,Casimir IV of Polandgranted the town theGreat Privilege,after he had been invited by the town's council and had already stayed in town for five weeks.[60]With theGreat Privilege,the town was granted full autonomy and protection by the King of Poland.[61]The privilege removed tariffs and taxes on trade within Poland, Lithuania, and Ruthenia (present dayBelarusandUkraine), and conferred on the town independent jurisdiction, legislation and administration of her territory, as well as the right to mint its own coin.[60]Furthermore, the privilege unitedOld Town,Osiek,andMain Town,and legalised the demolition ofNew Town,which had sided with theTeutonic Knights.[60]By 1457,New Townwas demolished completely, no buildings remained.[44]

Gaining free and privileged access to Polish markets, the seaport prospered while simultaneously trading with the other Hanseatic cities. After theSecond Peace of Thorn (1466)between Poland and the Teutonic Order the warfare ended permanently; Gdańsk became part of the Polish province ofRoyal Prussia,and later also of theGreater Poland Province.The city was visited byNicolaus Copernicusin 1504 and 1526, andNarratio Prima,the first printed abstract of hisheliocentric theory,was published there in 1540.[62]After theUnion of Lublinbetween Poland and Lithuania in 1569 the city continued to enjoy a large degree of internal autonomy (cf.Danzig law). Being the largest and one of the most influential cities of Poland, it enjoyed voting rights during theroyal electionperiod in Poland.

In the 1560s and 1570s, a largeMennonitecommunity started growing in the city, gaining significant popularity.[63]In the 1575 election to the Polish throne, Danzig supportedMaximilian IIin his struggle againstStephen Báthory.It was the latter who eventually became monarch but the city, encouraged by the secret support ofDenmarkandEmperor Maximilian,shut its gates against Stephen. After theSiege of Danzig,lasting six months, the city's army of 5,000 mercenaries was utterly defeated in a field battle on 16 December 1577. However, since Stephen's armies were unable to take the city by force, a compromise was reached:Stephen Báthoryconfirmed the city's special status and herDanzig lawprivileges granted by earlierPolish kings.The city recognised him as ruler of Poland and paid the enormous sum of 200,000guldensin gold as payoff ( "apology" ).[64]

During thePolish–Swedish War of 1626–1629,in 1627, the navalBattle of Oliwawas fought near the city, and it is one of the greatest victories in the history of thePolish Navy.During the Swedish invasion of Poland of 1655–1660, commonly known as theDeluge,the city was unsuccessfullybesieged by Sweden.In 1660, the war was ended with theTreaty of Oliwa,signed in the present-day district ofOliwa.[65]In 1677, a Polish-Swedish alliance was signed in the city.[66]Around 1640,Johannes Heveliusestablished hisastronomical observatoryin theOld Town.Polish KingJohn III Sobieskiregularly visited Hevelius numerous times.[67]

Beside a majority of German-speakers,[68]whose elites sometimes distinguished their German dialect asPomerelian,[69]the city was home to a large number of Polish-speaking Poles, Jewish Poles,Latvian-speakingKursenieki,Flemings,andDutch.In addition, a number ofScotstook refuge or migrated to and received citizenship in the city, with first Scots arriving in 1380.[70]During theProtestant Reformation,most German-speaking inhabitants adoptedLutheranism.Due to the special status of the city and significance within thePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth,the city inhabitants largely became bi-cultural sharing both Polish and German culture and were strongly attached to the traditions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[71]

The city suffered alast great plagueand a slow economic decline due to the wars of the 18th century. After peace was restored in 1721, Danzig experienced steady economic recovery. As a stronghold ofStanisław Leszczyński's supporters during theWar of the Polish Succession,it was taken by theRussiansafter theSiege of Danzigin 1734. In the 1740s and 1750s Danzig was restored and Danzig port was again the most significant grain exporting in theBaltic region.[72]TheDanzig Research Society,which became defunct in 1936, was founded in 1743.[73]

In 1772, theFirst Partition of Polandtook place andPrussiaannexed almost all of the former Royal Prussia, which became theProvince of West Prussia.However, Gdańsk remained a part of Poland as anexclaveseparated from the rest of the country. ThePrussian kingcut off Danzig with a military controlled barrier, also blocking shipping links to foreign ports, on the pretense that acattle plaguemay otherwise break out. Danzig declined in its economic significance. However, by the end of the 18th century, Gdańsk was still one of the most economically integrated cities in Poland. It was well-connected and traded actively withGerman cities,while otherPolish citiesbecame less well-integrated towards the end of the century, mostly due to greater risks for long-distancetrade,given the number ofviolentconflicts along the trade routes.[74]

Prussia and Germany

[edit]Danzig was annexed by theKingdom of Prussiain 1793,[75]in theSecond Partition of Poland.Both the Polish and the German-speaking population largely opposed the Prussian annexation and wished the city to remain part of Poland.[76]The mayor of the city stepped down from his office due to the annexation.[77]The notable city councilor Jan (Johann) Uphagen, historian and art collector, also resigned as a sign of protest against the annexation. His house exemplifiesBaroque in Polandand is now a museum, known asUphagen's House.[78]An attempted student uprising against Prussia led by Gottfried Benjamin Bartholdi was crushed quickly by the authorities in 1797.[79][80][81]

During theNapoleonic Wars,in 1807, the city wasbesieged and capturedby a coalition ofFrench,Polish,Italian,Saxon,andBadenforces. Afterwards, it was afree cityfrom 1807 to 1814, when it wascapturedby combined Prussian-Russian forces.

In 1815, after France's defeat in theNapoleonic Wars,it again became part of Prussia and became the capital ofRegierungsbezirk Danzigwithin the province ofWest Prussia.Since the 1820s, theWisłoujście Fortressserved as a prison, mainly for Polish political prisoners, includingresistance members,protesters, insurgents of theNovemberandJanuaryuprisings and refugees from theRussian Partitionof Poland fleeing conscription into the Russian Army,[82]and insurgents of the November Uprising were also imprisoned inBiskupia Górka(Bischofsberg).[83]In May–June 1832 and November 1833, more than 1,000 Polish insurgents departed partitioned Poland through the city's port, boarding ships bound forFrance,theUnited Kingdomand theUnited States(seeGreat Emigration).[84][85]

The city's longest serving mayor was Robert von Blumenthal, who held office from 1841, through therevolutions of 1848,until 1863. With theunification of Germanyin 1871 under Prussianhegemony,the city became part of theGerman Empireand remained so until 1919, after Germany's defeat inWorld War I.[75]Starting from the 1850s, long-established Danzig families often felt marginalized by the new town elite originating from mainland Germany. This situation caused the Polish to allege that the Danzig people were oppressed by German rule and for this reason allegedly failed to articulate their natural desire for strong ties with Poland.[86]

Free City of Danzig and World War II

[edit]

When Poland regained its independence afterWorld War Iwith access to the sea as promised by theAllieson the basis ofWoodrow Wilson's "Fourteen Points"(point 13 called for" an independent Polish state "," which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea "), the Poles hoped the city's harbour would also become part of Poland.[87]However, in the end – since Germans formed a majority in the city, with Poles being a minority (in the 1923 census 7,896 people out of 335,921 gave Polish, Kashubian, orMasurianas their native language)[88]– the city was not placed under Polish sovereignty. Instead, in accordance with the terms of theVersailles Treaty,it became theFree City of Danzig,an independent quasi-state under the auspices of theLeague of Nationswith its external affairs largely under Polish control.[89]Poland's rights also included free use of the harbour, a Polish post office, a Polish garrison in Westerplatte district, and customs union with Poland.[89]The Free City had its own constitution,national anthem,parliament,and government (Senat). It issued its own stamps as well as its currency, theDanzig gulden.[87]

With the growth ofNazismamong Germans,anti-Polish sentimentincreased and bothGermanisationandsegregationpolicies intensified, in the 1930s the rights of local Poles were commonly violated and limited by the local administration.[89]Polish children were refused admission to public Polish-language schools, premises were not allowed to be rented to Polish schools and preschools.[90]Due to such policies, only eight Polish-language public schools existed in the city, and Poles managed to organize seven more private Polish schools.[90]

In the early 1930s, the localNazi Partycapitalised on pro-German sentiments and in 1933 garnered 50% of vote in the parliament. Thereafter, the Nazis underGauleiterAlbert Forsterachieved dominance in the city government, which was still nominally overseen by the League of Nations'High Commissioner.

In 1937, Poles who sent their children to private Polish schools were required to transfer children to German schools, under threat of police intervention, and attacks were carried out on Polish schools and Polish youth.[90]German militias carried out numerous beatings of Polish activists, scouts and even postal workers, as "punishment" for distributing the Polish press.[91]German students attacked and expelled Polish students from the technical university.[91]Dozens of Polish surnames were forcibly Germanized,[91]while Polish symbols that reminded that for centuries Gdańsk was part of Poland were removed from the city's landmarks, such as theArtus Courtand theNeptune's Fountain.[92]

From 1937, the employment of Poles by German companies was prohibited, and already employed Poles were fired, the use of Polish in public places was banned and Poles were not allowed to enter several restaurants, in particular those owned by Germans.[92]In 1939, before the Germaninvasion of Polandand outbreak ofWorld War II,local Polish railwaymen were victims of beatings, and after the invasion, they were also imprisoned and murdered inconcentration camps.[93]

The German governmentofficially demanded the return of Danzig to Germany along with an extraterritorial (meaning under Germanjurisdiction) highway through the area of thePolish Corridorfor land-based access from the rest of Germany. Hitler used the issue of the status of the city as a pretext for attacking Poland and in May 1939, during a high-level meeting of German military officials explained to them: "It is not Danzig that is at stake. For us it is a matter of expanding ourLebensraumin the east ", adding that there will be no repeat of the Czech situation, and Germany will attack Poland at first opportunity, after isolating the country from its Western Allies.[94][95][96][97][98]

After the German proposals to solve the three main issues peacefully were refused, German-Polish relations rapidly deteriorated. Germanyattacked Polandon 1 September after having signeda non-aggression pactwith the Soviet Union.[99]

The German attack began in Danzig, with a bombardment of Polish positions atWesterplatteby the German battleshipSchleswig-Holstein,and the landing of German infantry on the peninsula. Outnumbered Polish defenders at Westerplatteresistedfor seven days before running out of ammunition. Meanwhile, after a fierce day-longfight(1 September 1939), defenders of the Polish Post office were tried and executed then buried on the spot in the Danzig quarter ofZaspain October 1939. In 1998 a German court overturned their conviction and sentence.[99]The city was officially annexed byNazi Germanyand incorporated into theReichsgau Danzig-West Prussia.

About 50 percent of members of theJewish communityhad left the city within a year after apogromin October 1937.[100]After theKristallnachtriots in November 1938, the community decided to organize its emigration[101]and in March 1939 a first transport toPalestinestarted.[102]By September 1939 barely 1,700 mostly elderly Jews remained. In early 1941, just 600 Jews were still living in Danzig, most of whom were later murdered in theHolocaust.[100][103]Out of the 2,938Jewish communityin the city, 1,227 were able to escape from the Nazis before the outbreak of war.[104]

Nazi secret policehad been observing Polish minority communities in the city since 1936, compiling information, which in 1939 served to prepare lists of Poles to be captured inOperation Tannenberg.On the first day of the war, approximately 1,500ethnic Poleswere arrested, some because of their participation in social and economic life, others because they were activists and members of various Polish organisations. On 2 September 1939, 150 of them were deported to theSicherheitsdienst camp Stutthofsome 50 km (30 mi) from Danzig, and murdered.[105]Many Poles living in Danzig were deported to Stutthof or executed in thePiaśnica forest.[106]

During the war, Germany operated a prison in the city,[107]anEinsatzgruppen-operated penal camp,[108]a camp forRomani people,[109]two subcamps of theStalag XX-Bprisoner-of-war campforAlliedPOWs,[110]and several subcamps of theStutthof concentration campwithin the present-day city limits.[111]

In 1941,Hitlerordered theinvasion of the Soviet Union,eventually causing the fortunes of war to turn against Germany. As theSoviet Armyadvanced in 1944, German populations inCentraland Eastern Europe took flight, resulting in the beginning of a great population shift. After thefinal Soviet offensivesbegan in January 1945, hundreds of thousands of German refugees converged on Danzig, many of whom had fled on foot fromEast Prussia,some tried to escape through the city's port in a large-scale evacuation involving hundreds of German cargo and passenger ships. Some of the ships were sunk by the Soviets, including theWilhelm Gustloffafter an evacuation was attempted at neighbouringGdynia.In the process, tens of thousands of refugees were killed.[112]

The city also endured heavy Allied and Soviet air raids. Those who survived and could not escape had to face the Soviet Army, whichcaptured the heavily damaged city on 30 March 1945,[113]followed by large-scalerape[114]and looting.[115][116]

In line with the decisions made by the Allies at theYaltaandPotsdamconferences, the city became again part of Poland, although with a Soviet-installed communist regime, which stayed in power until theFall of Communismin the 1980s. The remaining German residents of the city who had survived the warfled or were expelledto postwar Germany. The city was repopulated by ethnicPoles;up to 18 percent (1948) of them had beendeported by the Sovietsintwo major wavesfrom pre-war easternPolish areas annexed by the Soviet Union.[117]

Post World War II (1945-1989)

[edit]In 1946, the communists executed 17-year-oldDanuta Siedzikównaand 42-year-oldFeliks Selmanowicz,knownPolish resistancemembers, in the local prison.[118][119]

The port of Gdańsk was one of the three Polish ports through whichGreeksandMacedonians,refugees of the Greek Civil War,reached Poland.[120]In 1949, four transports of Greek and Macedonian refugees arrived at the port of Gdańsk, from where they were transported to new homes in Poland.[120]

Parts of the historic old city of Gdańsk, which had suffered large-scale destruction during the war, were rebuilt during the 1950s and 1960s. The reconstruction sought to dilute the "German character" of the city, and set it back to how it supposedly looked like before the annexation to Prussia in 1793.[121][122][123]Nineteenth-century transformations were ignored as "ideologically malignant" by post-war administrations, or regarded as "Prussian barbarism" worthy of demolition,[124][125]while Flemish/Dutch, Italian and French influences were emphasized in order to "neutralize" the German influx on the general outlook of the city.[126]

Boosted by heavy investment in the development of its port and three major shipyards for Soviet ambitions in theBaltic region,Gdańsk became the major shipping and industrial centre of thePeople's Republic of Poland.In December 1970, Gdańsk was the scene ofanti-regime demonstrations,which led to the downfall of Poland's communist leaderWładysław Gomułka.During the demonstrations in Gdańsk and Gdynia, military as well as the police opened fire on the demonstrators causing several dozen deaths. Ten years later, in August 1980,Gdańsk Shipyardwas the birthplace of theSolidaritytrade union movement.[127]

In September 1981, to deter Solidarity, Soviet Union launchedExercise Zapad-81,the largest military exercise in history, during which amphibious landings were conducted near Gdańsk. Meanwhile, the Solidarity held its first national congress inHala Olivia,Gdańsk when more than 800 deputies participated. Its opposition to the Communist regime led to the end of Communist Party rule in 1989, and sparked a series of protests that overthrew the Communist regimes of the formerEastern Bloc.[128]

Contemporary history (1990-present)

[edit]Solidarity's leader,Lech Wałęsa,becamePresident of Polandin 1990. In 2014 theEuropean Solidarity Centre,a museum and library devoted to the history of the movement, opened in Gdańsk.[128]

On 9 July 2001, the city was flooded, with 200 millionzłbeing estimated in damage, 4 people killed, and 304 evacuated. As a result, the city has built 50 reservoirs, the number of which is rising.[129][130]

Gdańsk nativeDonald TuskisPrime Minister of Polandfrom 2007 to 2014 and again from 2023 to present and wasPresident of the European Councilfrom 2014 to 2019.[131]In 2014, the remains ofDanuta Siedzikównaand Feliks Selmanowicz were found at the local Garrison Cemetery, and then their state burial was held in Gdańsk in 2016, with the participation of thousands of people from all over Poland and the highest Polish authorities.[119]

In January 2019, the Mayor of Gdańsk,Paweł Adamowicz,wasassassinatedby a man who had just been released from prison for violent crimes. After stabbing the mayor in the abdomen near the heart, the man claimed that the mayor's political party had been responsible for imprisoning him. Though Adamowicz underwent a multi-hour surgery, he died the next day.[132][133]

In October 2019, the City of Gdańsk was awarded thePrincess of Asturias Awardin the Concord category as a recognition of the fact that "the past and present in Gdańsk are sensitive to solidarity, the defense of freedom and human rights, as well as to the preservation of peace".[134]

In a 2023 Report on the Quality of Life in European Cities compiled by theEuropean Commission,Gdańsk was named as the fourth best city to live in Europe alongsideLeipzig,StockholmandGeneva.[135]

Geography

[edit]Gdańsk lies at the mouth of theMotławariver to theMartwa Wisła,a branch of theVistula.It is located on the border between differentphysiographic regions:Vistula Spit(waterside part of the city),Vistula Fens(eastern part of the city),Kashubian Coastland(north-western part of the city) andKashubian Lake District(western part of the city).

Climate

[edit]| Gdańsk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gdańsk has a climate with both oceanic and continental influences. According to some categorizations, it has anoceanic climate(Cfb), while others classify it as belonging to thehumid continental climate(Dfb).[136]It actually depends on whether the mean reference temperature for the coldest winter month is set at −3 °C (27 °F) or 0 °C (32 °F). Gdańsk's dry winters and the precipitation maximum in summer are indicators of continentality. However seasonal extremes are less pronounced than those in inland Poland.[137]

The city has moderately cold and cloudy winters with mean temperature in January and February near or below 0 °C (32 °F) and mild summers with frequent showers and thunderstorms. Average temperatures range from −1.0 to 17.2 °C (30 to 63 °F) and average monthly rainfall varies 17.9 to 66.7 mm (1 to 3 in) per month with a rather low annual total of 507.3 mm (20 in). In general, the weather is damp, variable, and mild.[137]

The seasons are clearly differentiated. Spring starts in March and is initially cold and windy, later becoming pleasantly warm and often increasingly sunny. Summer, which begins in June, is predominantly warm but hot at times with temperature reaching as high as 30 to 35 °C (86 to 95 °F) at least couple times a year with plenty of sunshine interspersed with heavy rain. Gdańsk averages 1,700 hours of sunshine per year. July and August are the warmest months. Autumn comes in September and is at first warm and usually sunny, turning cold, damp, and foggy in November. Winter lasts from December to March and includes periods of snow. January and February are the coldest months with the temperature sometimes dropping as low as −15 °C (5 °F).[137]

| Climate data for Gdańsk (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

32.3 (90.1) |

34.6 (94.3) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

28.1 (82.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.4 (−17.3) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.1 (35.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 28.5 (1.12) |

23.7 (0.93) |

27.5 (1.08) |

32.0 (1.26) |

53.3 (2.10) |

58.8 (2.31) |

79.4 (3.13) |

70.0 (2.76) |

64.5 (2.54) |

54.8 (2.16) |

42.6 (1.68) |

36.0 (1.42) |

571.0 (22.48) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 0.1 mm) | 16.67 | 14.25 | 14.03 | 11.43 | 13.07 | 14.03 | 13.43 | 14.03 | 12.40 | 15.27 | 15.93 | 17.97 | 172.51 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 87.7 | 85.9 | 82.5 | 75.5 | 71.6 | 72.2 | 74.7 | 78.1 | 82.6 | 84.6 | 89.1 | 89.8 | 81.2 |

| Averagedew point°C (°F) | −3 (27) |

−3 (27) |

−1 (30) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

12 (54) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

2 (36) |

−1 (30) |

4 (40) |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 39 | 70 | 134 | 163 | 244 | 259 | 236 | 225 | 174 | 105 | 45 | 32 | 1,726 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Source 1: Institute of Meteorology and Water Management[138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: meteomodel.pl,[e][146]Weather Atlas (UV),[147]Time and Date (dewpoints, 2005-2015)[148] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

The industrial sections of the city are dominated by shipbuilding, petrochemical, and chemical industries, as well as food processing. The share of high-tech sectors such as electronics, telecommunications, IT engineering, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals is on the rise.Amberprocessing is also an important part of the local economy, as the majority of the world's amber deposits lie along theBalticcoast.[149]

Major companies based in Gdańsk include multinational clothing companyLPP,Energa,Remontowa,theGdańsk Shipyard,Ziaja, andBreakThru Films.The city also served as a major base forGrupa Lotos,with theGdańsk Refineryhaving been the second-largest in Poland, with a capacity of 210,000 bbl/d (33,000 m3/d).[150][149]Gdańsk also hosts the biennial BALTEXPO International Maritime Fair and Conference, the largest fair dedicated to themaritime industryin Poland.[151][152]

The largest shopping center located in the city isForum Gdańsk,[153]which covers a large plot in the city centre.[154]In 2021, the registered unemployment rate in the city was estimated at 3.6%.[155]

Main sights

[edit]Architecture

[edit]The city has some buildings surviving from the time of theHanseatic League.Mosttourist attractionsare located in the area of the Main City of Gdańsk,[156]along or near Ulica Długa (Long Street) and Długi Targ (Long Market), a pedestrian thoroughfare surrounded by buildings reconstructed in historical (primarily during the 17th century) style and flanked at both ends by elaboratecity gates.This part of the city is sometimes referred to as the Royal Route, since it was once the path of processions for visiting Kings of Poland.[157]

Walking from end to end, sites encountered on or near the Royal Route include:[157]

- Highland Gate (Brama Wyżynna), which marks the beginning of the Royal Route

- Torture House (Katownia) and Prison Tower (Wieża więzienna), now housing the Amber Museum (Muzeum Bursztynu)

- Mansion of the Society of Saint George (Dwór Bractwa św. Jerzego)

- Golden Gate(Złota Brama)[158]

- Ulica Długa( "Long Lane" ), filled with picturesque tenements

- Uphagen's House(Dom Uphagena), branch of the Museum of Gdańsk

- Lion's Castle (Lwi Zamek)

- Main Town Hall(Ratusz Głównego Miasta,built 1378–1492)[159]

- Długi Targ( "Long Market" )

- Artus' Court(Dwór Artusa)[160]

- Neptune's Fountain(Fontanna Neptuna), a masterpiece by architectAbraham van den Blocke,1617.[161][162]It is the oldest working fountain in Poland.[163]

- New Jury House (Nowy Dom Ławy), in which the seemingly 17th-centuryMaiden in the Windowappears every day during the tourist season, referring to a popular novelPanienka z okienka( "Maiden in the Window" ) byJadwiga Łuszczewska,set in 17th-century Gdańsk[164]

- Golden House (Złota Kamienica), a distinctiveRenaissancetownhouse from the early 17th century, decorated with numerous reliefs and sculptures[165]

- Green Gate(Zielona Brama), aManneristgate, built as a formal residence of Polish kings, now housing a branch of theNational Museum in Gdańsk[166]

- Olivia Business Centre,a district made up of six buildings

- Olivia Star, the tallest building in Gdańsk and the rest of northern Poland. It was finished in 2018 and measures at 156 metres (512 ft).[167]

Gdańsk has a number of historical churches, includingSt. Catherine's ChurchandSt. Mary's Church(Bazylika Mariacka). This latter is a municipal church built during the 15th century, and is one of the largest brick churches in the world.[157]The city's 17th-century fortifications represent one of Poland's official nationalHistoric Monuments(Pomnik historii), as designated on 16 September 1994 and tracked by theNational Heritage Board of Poland.[169]

Other main sights in the historical city centre include:[157]

- Royal Chapel of the Polish KingJohn III Sobieski

- Żuraw– medieval port crane[170]

- Granaries on theOłowiankaand Granary Islands

- John III Sobieski Monument

- Old Town Hall[171]

- Mariacka Street[172]

- Polish Post Office,site of the1939 battle

- Brick gothic town gates, i.e., Mariacka Gate, Straganiarska Gate, Cow Gate

Main sights outside the historical city centre include:[157]

- Abbot's Palacein the Oliwa Park

- Oliwa Cathedral

- Brzeźno Pier

- Medieval city walls

- Westerplatte[173]

- Wisłoujście Fortress[174]

- Gdańsk Zoo[175]

Museums

[edit]

- National Museum(Muzeum Narodowe)[176]

- Department of Ancient Art – contains a number of important artworks, includingHans Memling'sLast Judgement

- Green Gate

- Department of Modern Art – in theAbbot's Palacein Oliwa

- Ethnography Department – in the Abbot's Granary in Oliwa

- Gdańsk Photography Gallery

- Historical Museum (Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Gdańska):[177]

- Main Town Hall

- Artus' Court

- Uphagen's House

- Amber Museum (Muzeum Bursztynu)

- Museum of the Polish Post (Muzeum Poczty Polskiej)

- Wartownia nr 1 na Westerplatte

- Museum of Tower Clocks (Muzeum Zegarów Wieżowych)

- Wisłoujście Fortress

- National Maritime Museum, Gdańsk(Narodowe Muzeum Morskie):

- museum shipSS Sołdekis anchored on theMotławaRiver and was the first ship built in post-war Poland.

- European Solidarity Centre.Museum and library dedicated to the history of theSolidaritymovement.[178]

- Archdiocese Museum (Muzeum Archidiecezjalne)

- Museum of the Second World War[179]

Entertainment

[edit]- Polish Baltic Philharmonic

- Baltic Opera

- Gdańsk Shakespeare Theatreis a Shakespearean theatre built on the historical site of a 17th-century playhouse where English travelling players came to perform. The new theatre, completed in 2014, hosts the annualGdańsk Shakespeare Festival.[180]

Transport

[edit]

The city's core transport infrastructure includesGdańsk Lech Wałęsa Airport,an international airport located in Gdańsk,[181] and theSzybka Kolej Miejska,(SKM)[182]which functions as arapid transitsystem for the Tricity area, including Gdańsk,SopotandGdynia,operating frequent trains to 27 stations covering the Tricity.,[183]as well as the long-distance railways.

The principal station in Gdańsk isGdańsk Główny railway station,served by bothSKMlocal trains andPKPlong-distance trains. In addition, long-distance trains also stop atGdańsk Oliwa railway station,Gdańsk Wrzeszcz railway station,Sopot,andGdynia.Gdańsk also has nine other railway stations, served by localSKMtrains;[182]Long-distance trains are operated byPKP Intercitywhich provides connections with all majorPolish cities,includingWarsaw,Kraków,Łódź,Poznań,Katowice,Szczecin,andCzęstochowa,and with the neighbouring Kashubian Lakes region.[184]

Between 2011 and 2015, the rail route between Gdańsk, Gdynia, and Warsaw underwent a major upgrade, resulting in improvements in the railway's speed and critical infrastructure such as signalling systems, as well as the construction of thePomorska Kolej Metropolitalna,a major suburban railway, which was opened in 2015.[185][186][187]

City buses andtramsare operated by ZTM Gdańsk (Zarząd Transportu Miejskiego w Gdańsku).[188]ThePort of Gdańskis a seaport located on the southern coast ofGdańsk Bay,located within the city,[189]and theObwodnica TrójmiejskaandA1 autostradaallow for automotive access to the city.[190]Additionally, Gdańsk is part of theRail-2-Seaproject. This project's objective is to connect the city with the RomanianBlack Seaport ofConstanțawith a 3,663 km (2,276 mi) long railway line passing through Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania.[191][192]

Sport

[edit]

There are many popular professional sports teams in the Gdańsk and Tricity area. The city's professionalfootballclub isLechia Gdańsk.[193]Founded in 1945, they play in theEkstraklasa,Poland's top division. Their home stadium,Stadion Miejski,[194]was one of the four Polish stadiums to host theUEFA Euro 2012competition,[195]as well as the host of the2021 UEFA Europa League Final.[196]Other notable football clubs areGedania 1922 GdańskandSKS Stoczniowiec Gdańsk,which both played in the second tier in the past.[197][198]Other notable clubs include speedway clubWybrzeże Gdańsk,[199]rugby clubLechia Gdańsk,[200]ice hockey clubStoczniowiec Gdańsk,[201]and volleyball clubTrefl Gdańsk.[202]

The city'sHala Oliviawas a venue for the official2009 EuroBasket,[203]and theErgo Arenawas one of the2013 Men's European Volleyball Championship,2014 FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championshipand2014 IAAF World Indoor Championshipsvenues.[204][205][206]

Politics and local government

[edit]

Contemporary Gdańsk is one of the major centres of economic and administrative life in Poland. It has been the seat of a Polish central institution, thePolish Space Agency,[207]several supra-regional branches of further central institutions,[208]as well as the supra-regional (appellate-level) institutions of justice.[209]As the capital of thePomeranian Voivodeshipit has been the seat of the Pomeranian Voivodeship Office, the Sejmik, and the Marshall's Office of the Pomeranian Voivodeship and other voivodeship-level institutions.[210]

Legislative power in Gdańsk is vested in a unicameral Gdańskcity council(Rada Miasta), which comprises 34 members. Council members are elected directly every four years. Like most legislative bodies, the City Council divides itself into committees, which have the oversight of various functions of the city government.[211]

- City Council in 2024–2029

Districts

[edit]Gdańsk is divided into 34 administrative divisions: 6dzielnicasand 28osiedles.A full list can be found atDistricts of Gdańsk,but the largest includeŚródmieście,Przymorze Wielkie,Chełm,Wrzeszcz Dolny,andWrzeszcz Górny.[212]

Education and science

[edit]

There are 15 higher schools in the city, including three universities. Notable educational institutions include theUniversity of Gdańsk,Gdańsk University of Technology,andGdańsk Medical University.[213][214][215]The city is also home to theBaltic Institute.[216]

International relations

[edit]Consulates

[edit]

There are four consulates general in Gdańsk –China,Germany,Hungary,Russia,one consulate –Ukraine,and 17 honorary consulates –Austria,Bangladesh,Bulgaria,Estonia,Ethiopia,Kazakhstan,Latvia,Lithuania,Mexico,Moldova,Netherlands,Peru,Seychelles,Spain,Sri Lanka,Sweden,Uruguay.[217]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Former twin towns

[edit] Kaliningrad,Russia

Kaliningrad,Russia Saint Petersburg,Russia

Saint Petersburg,Russia

On 3 March 2022, Gdańsk City Council passed a unanimous resolution to terminate the cooperation with the Russian cities of Kaliningrad and Saint Petersburg as a response to theRussian invasion of Ukraine.[219][220]

Partnerships and cooperation

[edit]Gdańsk also cooperates with:[218]

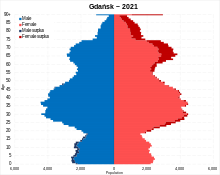

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 120,338 | — |

| 1910 | 170,337 | +41.5% |

| 1929 | 256,403 | +50.5% |

| 1945 | 139,078 | −45.8% |

| 1946 | 117,894 | −15.2% |

| 1950 | 194,633 | +65.1% |

| 1960 | 286,940 | +47.4% |

| 1970 | 365,600 | +27.4% |

| 1978 | 442,118 | +20.9% |

| 1988 | 464,308 | +5.0% |

| 2002 | 461,334 | −0.6% |

| 2011 | 460,276 | −0.2% |

| 2021 | 486,022 | +5.6% |

| source[223][224][225] | ||

The 1923 census conducted in the Free City of Danzig indicated that of all inhabitants, 95% were German, and 3% were Polish and Kashubian. The end ofWorld War IIis a significant break in continuity with regard to the inhabitants of Gdańsk.[226]

German citizens began to flee en masse as the SovietRed Armyadvanced, composed of both spontaneous flights driven by rumors ofSoviet atrocities,and organised evacuation starting in the summer of 1944 which continued into the spring of 1945.[227]Approximately 1% (100,000) of the German civilian population residing east of theOder–Neisse lineperished in the fighting prior to the surrender in May 1945.[228]German civilians were also sent as "reparations labour" to theSoviet Union.[229][230]

Poles from other parts of Poland replaced the former German-speaking population, with the first settlers arriving in March 1945.[231]On 30 March 1945, theGdańsk Voivodeshipwas established as the first administrative Polish unit in theRecovered Territories.[232]As of 1 November 1945, around 93,029 Germans remained within the city limits.[233]The locals of German descent who declared Polish nationality were permitted to remain; as of 1 January 1949, 13,424 persons who had received Polish citizenship in a post-war "ethnic vetting" process lived in Gdańsk.[234]

The settlers can be grouped according to their background:

- Poles that had been freed fromforced labor in Nazi Germany[235][236]

- Repatriates:Poles expelled from the areas east of the new Polish-Soviet border. This included assimilated minorities such asthe Polish-Armenian community[235][236]

- Poles incl.Kashubiansrelocating from nearby villages and small towns[237]

- Settlers from central Poland migrating voluntarily[235]

- Non-Poles forcibly resettled duringOperation Vistulain 1947. Large numbers of Ukrainians were forced to move from south-eastern Poland under a 1947 Polish government operation aimed at dispersing, and therefore assimilating, those Ukrainians who had not been expelled eastward already, throughout the newly acquired territories. Belarusians living around the area around Białystok were also pressured into relocating to the formerly German areas for the same reasons. This scattering of members of non-Polish ethnic groups throughout the country was an attempt by the Polish authorities to dissolve the unique ethnic identity of groups like the Ukrainians, Belarusians, andLemkos,and broke the proximity and communication necessary for strong communities to form.[238]

- JewishHolocaustsurvivors, most of themPolish repatriatesfrom theEastern Borderlands.[239]

- GreeksandSlav Macedonians,refugees of the Greek Civil War.[240]

People

[edit]See also

[edit]- Tourism in Poland

- List of honorary citizens of Gdańsk

- 764 Gedania– a minor planet orbiting the Sun

- Danzig Highflyer

- Father Eugeniusz Dutkiewicz SAC Hospice

- Kashubians

- List of neighbourhoods of Gdańsk

- St. Mary's Church, Gdańsk

- Laznia Centre for Contemporary Art

- Ronald Reagan Park

- Live in Gdańsk

- Orunia Park

Notes

[edit]- ^

- Pronunciation:

- British English:/ɡəˈdænsk/gə-DANSK

- American English:USalso/ɡəˈdɑːnsk/gə-DAHNSK[5]

- Polish:Polish:[ɡdaj̃sk].

- Other names:

- Kashubian:Gduńsk[ɡduɲsk][6]

- German:Danzig[ˈdantsɪç]or[ˈdantsɪk]

- Latin:Gedania,GedaniumorDantiscum.[7]

- Pronunciation:

- ^Also in 1454, 1468, 1484, and 1590

- ^Also in 1399, 1410, and 1414–1438

- ^Also in 1410, 1414

- ^Record temperatures are from all Gdańsk stations.

References

[edit]- ^[1]Archived2023-02-01 at theWayback Machine(in Polish)

- ^"Największe miasta w Polsce. Warszawa wyprzedzona, jest nowy lider".TVN24.27 July 2023.Retrieved31 August2023.

- ^"Powierzchnia i ludność w przekroju terytorialnym w 2023 roku".Główny Urząd Statystyczny.20 July 2023.Retrieved31 August2023.

- ^"Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions".ec.europa.eu.

- ^"the definition of gdansk".Dictionary.

- ^Stefan Ramułt,Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego,Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6.

- ^abJohann Georg Theodor Grässe,Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benennungen der bekanntesten Städte etc., Meere, Seen, Berge und Flüsse in allen Theilen der Erde nebst einem deutsch-lateinischen Register derselben.T. Ein Supplement zu jedem lateinischen und geographischen Wörterbuche. Dresden: G. Schönfeld's Buchhandlung (C. A. Werner), 1861, p. 71, 237.

- ^"Local Data Bank".Statistics Poland.Retrieved18 July2022.Data for territorial unit 2261000.

- ^"Poland – largest cities (per geographical entity)".World Gazetteer.Retrieved5 May2009.[dead link]

- ^"Obszar Metropolitalny Gdańsk-Gdynia-Sopot"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 17 April 2021.Retrieved17 April2021.

- ^"Wszystkie Strony Miasta. Rok 2019 rekordowy w gdańskiej turystyce - 3,4 mln gości".gdansk.pl(in Polish).Retrieved17 December2022.

- ^"Saint Dominic's Fair is 760 years old!".Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2020.Retrieved5 August2020.

- ^"Millions at Gdansk's St. Dominic's Fair".pap.pl.21 August 2016.Retrieved30 December2016.

- ^"Pomniki historii".nid.pl.Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa. n.d. Archived fromthe originalon 11 October 2021.Retrieved11 October2021.

- ^"Quality of Life Index by City 2019 Mid-Year".numbeo.Archivedfrom the original on 12 June 2019.Retrieved20 September2019.

- ^"Wyborcza.pl".trojmiasto.wyborcza.pl.Archivedfrom the original on 12 March 2020.Retrieved20 September2019.

- ^"Gdańsk high in Quality of Life Index".en.ug.edu.pl.Archived fromthe originalon 20 September 2019.Retrieved20 September2019.

- ^Breza, Edward (2002).Nazwiska Pomorzan. Pochodzenie i zmiany.Vol. 2. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego. p. 90.ISBN9788373260573.OCLC643402493.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved1 November2021.

- ^Mamok, Szymon (8 October 2020)."Gdańsk. Skąd wzięła się nazwa miasta".Historia Gdańska.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2021.Retrieved31 October2021.

- ^Gumowski, Marian (1966).Handbuch der polnischen Siegelkunde(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 8 October 2021.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^Tighe, Carl (1990).Gdańsk: national identity in the Polish-German borderlands.Pluto Press.ISBN9780745303468.Archivedfrom the original on 8 October 2021.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^Treder, Jerzy (2007). "Historyk o nazwach" Gdańsk "i" Gdania "".Acta Cassubiana.9:48.

- ^abcŚliwiński 2006,p. 12.

- ^Gdańsk, in: Kazimierz Rymut,Nazwy Miast Polski,Ossolineum,Wrocław 1987

- ^Hubert Gurnowicz,Gdańsk,in:Nazwy must Pomorza Gdańskiego,Ossolineum,Wrocław 1978

- ^Baedeker's Northern Germany,Karl Baedeker Publishing,Leipzig 1904

- ^Labuda, Aleksander."Gduńsk, nasz stoleczny gard"(PDF).Zrzesz Kaszëbskô.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 March 2022.Retrieved10 December2022.

- ^"Gdańsk na przestrzeni dziejów".Trójmiasto.pl Historia.Trójmiasto.Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2021.Retrieved15 December2021.

- ^"Gdańsk – jedno z najstarszych polskich miast".Polska Tampa Bay.9 April 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2021.Retrieved15 December2021.

- ^"GDAŃSK – POCZĄTKI MIASTA".Gedanopedia.Gdańsk Foundation. 25 December 2019. Archived fromthe originalon 9 June 2020.Retrieved15 December2021.

- ^"The Crane: past and present – Crane – National Maritime Museum in Gdańsk".en.nmm.pl.Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2019.Retrieved16 April2019.

- ^abLoew, Peter Oliver: Danzig. Biographie einer Stadt, Munich 2011, p. 24.

- ^abWazny, Tomasz; Paner, Henryk; Golebiewski, Andrzej; Koscinski, Bogdan: Early medieval Gdańsk/Danzig revisited (EuroDendro 2004), Rendsburg 2004,pdf-abstractArchived9 September 2013 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Loew (2011), p. 24; Wazny et al. (2004),abstractArchived9 September 2013 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Hess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 39.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^admin2."1000 LAT GDAŃSKA W ŚWIETLE WYKOPALISK".Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2017.Retrieved18 March2017.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^abHess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 40.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^Zbierski, Andrzej (1978).Struktura zawodowa, spoleczna i etnicza ludnosci. In Historia Gdanska, Vol. 1.Wydawnictwo Morskie. pp. 228–9.ISBN978-83-86557-00-4.

- ^Turnock, David (1988).The Making of Eastern Europe: From the Earliest Times to 1815.Routledge. p. 180.ISBN978-0-415-01267-6.

- ^Harlander, Christa (2004).Stadtanlage und Befestigung von Danzig (zur Zeit des Deutschen Ordens).GRIN Verlag. p. 2.ISBN978-3-638-75010-3.

- ^Lingenberg, Heinz (1982).Die Anfänge des Klosters Oliva und die Entstehung der deutschen Stadt Danzig: die frühe Geschichte der beiden Gemeinwesen bis 1308/10.Klett-Cotta. p. 292.ISBN978-3-129-14900-3.

- ^'The Slippery Memory of Men': The Place of Pomerania in the Medieval Kingdom of Poland by Paul Milliman p. 73, 2013

- ^Hess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 40–41.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^abcdHess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 41.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^abcHartmut Boockmann,Ostpreußen und Westpreußen,Siedler, 2002, p. 158,ISBN3-88680-212-4

- ^abJames Minahan, One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000,ISBN0-313-30984-1,p. 376 Google BooksArchived2 November 2020 at theWayback Machine

- ^Thomas Urban:"Rezydencja książąt Pomorskich".(in Polish)Archived25 August 2005 at theWayback Machine

- ^Hess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 41–42.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^Frankot, Edda (2012).'Of Laws of Ships and Shipmen': Medieval Maritime Law and its Practice in Urban Northern Europe.Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 100.ISBN978-0-7486-4624-1.

- ^abHess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 42.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^Loew, Peter O. (2011).Danzig: Biographie einer Stadt.München: C.H. Beck. p. 43.ISBN978-3-406-60587-1.

- ^Sobecki, Sebastian (2016).Europe: A Literary History, 1348–1418, ed. David Wallace.Oxford University Press. pp. 635–41.ISBN9780198735359.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2016.Retrieved2 June2016.

- ^"II Pokój Toruński i przyłączenie Gdańska do Rzeczpospolitej".mgdansk.pl.Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2014.Retrieved16 September2014.

- ^Górski, Karol (1949).Związek Pruski i poddanie się Prus Polsce: zbiór tekstów źródłowych(in Polish). Poznań: Instytut Zachodni. pp. 16, 18.

- ^Górski, pp. 51, 56

- ^Górski, p. 63

- ^Górski, pp. 71-72

- ^Górski, pp. 79-80

- ^"Danzig – Gdańsk until 1920".[permanent dead link]

- ^abcHess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 45.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.

- ^Hess, Corina (2007).Danziger Wohnkultur in der frühen Neuzeit.Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 45.ISBN978-3-8258-8711-7.:"Geben wir und verlehen unnsir Stadt Danczk das sie zcu ewigen geczeiten nymands for eynem herrn halden noc gehorsam zcu weszen seyn sullen in weltlichen sachen."

- ^"Gdańsk".Szlak Kopernikowski(in Polish).Retrieved11 January2024.

- ^de Graaf, Tjeerd (2004).The Status of an Ethnic Minority in Eurasia: The Mennonites and Their Relation with the Netherlands, Germany and Russia.

- ^Włusek, Andrzej (23 May 2017)."Bitwa pod Lubieszowem w świetle wybranych źródeł pisanych".HistoryKon.

- ^Kosiarz, Edmund (1978).Wojny na Bałtyku X - XIX wiek.Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Morskie.

- ^Jonasson, Gustav (1980). "Polska i Szwecja za czasów Jana III Sobieskiego".Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka(in Polish).XXXV(2). Wrocław:Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich,WydawnictwoPolskiej Akademii Nauk:240.ISSN0037-7511.

- ^"Jan Heweliusz - życie i twórczość".Culture.pl.Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.Retrieved10 December2022.

- ^Zamoyski, Adam (2015).Poland. A History.William Collins. pp. 26, 92.ISBN978-0007556212.

- ^Bömelburg, Hans-Jürgen,Zwischen polnischer Ständegesellschaft und preußischem Obrigkeitsstaat: vom Königlichen Preußen zu Westpreußen (1756–1806),München: Oldenbourg, 1995, (Schriften des Bundesinstituts für Ostdeutsche Kultur und Geschichte (Oldenburg); 5), zugl.: Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg-Univ., Diss., 1993, p. 549

- ^Wijaczka, Jacek (2010). "Szkoci". In Kopczyński, Michał; Tygielski, Wojciech (eds.).Pod wspólnym niebem. Narody dawnej Rzeczypospolitej(in Polish). Warszawa: Muzeum Historii Polski, Bellona. p. 201.ISBN978-83-11-11724-2.

- ^Historia Polski 1795–1815Andrzej ChwalbaKraków 2000, p. 441

- ^Philip G. Dwyer (2014).The Rise of Prussia 1700-1830.Taylor & Francis. p. 134.ISBN9781317887034.

- ^Letkemann, Peter (2000)."Geschichte der Danziger Naturforschenden Gesellschaft".uni-marburg.de.University of Marburg.Archived from the original on 31 January 2005.Retrieved10 December2022.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^Baten, Jörg; Wallusch, Jacek (2005). "Market Integration and Disintegration of Poland and Germany in the 18th Century".Economies et Sociétés.

- ^abPlanet, Lonely."History of Gdańsk – Lonely Planet Travel Information".lonelyplanet.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2016.Retrieved29 July2016.

- ^Górski, p. XVI

- ^Andrzej Januszajtis,Karol Fryderyk von Conradi,"Nasz Gdańsk", 11 (196)/2017, p. 3 (in Polish)

- ^"Jan Uphagen".Gdańskie Autobusy i Tramwaje(in Polish). Archived fromthe originalon 19 February 2019.Retrieved1 April2020.

- ^Dzieje GdańskaEdmund Cieślak, Czesław Biernat Wydawn. Morskie, 1969 p. 370

- ^Dzieje Polski w datach Jerzy Borowiec,Halina Niemiec p. 161

- ^Polska, losy państwa i naroduHenryk Samsonowicz 1992 Iskry p. 282

- ^Kubus, Radosław (2019). "Ucieczki z twierdzy Wisłoujście w I połowie XIX wieku".Vade Nobiscum(in Polish).XX.Łódź: WydawnictwoUniwersytetu Łódzkiego:154–155.

- ^Kasparek, Norbert (2014). "Żołnierze polscy w Prusach po upadku powstania listopadowego. Powroty do kraju i wyjazdy na emigrację". In Katafiasz, Tomasz (ed.).Na tułaczym szlaku... Powstańcy Listopadowi na Pomorzu(in Polish). Koszalin: Muzeum w Koszalinie, Archiwum Państwowe w Koszalinie. p. 177.

- ^Kasparek, pp. 175–176, 178–179

- ^"Rozmaite wiadomości".Gazeta Wielkiego Xięstwa Poznańskiego(in Polish). No. 155. Poznań. 6 July 1832. p. 852.

- ^Loew, Peter Oliver (207). "Danzig oder das verlorene Paradies. Vom Herausgeben und vom Hineinerzählen".Germanoslavica Zeitschrift für germano-slawische Studien.28(1–2). Hildesheim: Verlag Georg Olms: 109–122.

- ^abAmtliche Urkunden zur Konvention zwischen Danzig und Polen vom 15. November 1920: zusammegestellt und mit Begleitbericht versehen von der nach Paris entsandten Delegation der Freien Stadt Danzig.Danzig: Biblioteka Uniwersytecka w Toruniu. 1920.

- ^Ergebnisse der Volks- und Berufszählung vom 1. November 1923 in der Freien Stadt Danzig(in German). Verlag des Statistischen Landesamtes der Freien Stadt Danzig. 1926..Polish estimates of the Polish minority during the interwar era, however, range from 37,000 to 100,000 (9%–34%). Studia historica Slavo-Germanica, Tomy 18–20page 220 Uniwersytet Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu. Instytut Historii Wydawnictwo Naukowe imienia. Adama Mickiewicza, 1994.

- ^abcWardzyńska, Maria (2009).Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion(in Polish). Warszawa:IPN.p. 37.

- ^abcWardzyńska, p. 40

- ^abcWardzyńska, p. 41

- ^abWardzyńska, p. 42

- ^Wardzyńska, pp. 39-40, 85

- ^The history of the German resistance, 1933–1945Peter Hoffmann p. 37 McGill-Queen's University Press 1996

- ^HitlerJoachim C. Fest p. 586 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2002

- ^Blitzkrieg w Polsce wrzesien 1939Richard Hargreaves p. 84 Bellona, 2009

- ^A military history of Germany, from the eighteenth century to the present dayMartin Kitchen p. 305 Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1975

- ^International history of the twentieth century and beyond Antony Best p. 181 Routledge; 2 edition (30 July 2008)

- ^abDrzycimski, Andrzej (2014).Reduta Westerplatte.Oficyna Gdańska.ISBN978-8364180187.

- ^ab"Gdansk".Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2017.Retrieved18 March2017.

- ^Bauer, Yehuda (1981).American Jewry and the Holocaust.Wayne State University Press. p. 145.ISBN978-0-8143-1672-6.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^"Die" Lösung der Judenfrage "in der Freien Stadt Danzig".shoa.de(in German). 30 November 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 29 June 2011.

- ^"Gdansk, Poland".jewishgen.org.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2018.Retrieved27 January2018.

- ^Żydzi na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska w latach 1920–1945:działalność kulturalna, polityczna i socjalnaGrzegorz Berendt Gdańskie Tow. Nauk., Wydz. I Nauk Społecznych i Humanistycznych, 1997 p. 245

- ^Museums Stutthof in SztutowoArchived24 August 2005 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- ^"Museums Stutthof".Archived fromthe originalon 24 August 2005.Retrieved16 January2006.

- ^"Schweres NS-Gefängnis Danzig, Neugarten 27".Bundesarchiv.de(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2021.Retrieved18 September2021.

- ^"Einsatzgruppen-Straflager in der Danziger Holzgasse".Bundesarchiv.de(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2021.Retrieved18 September2021.

- ^"Zigeunerlager Danzig".Bundesarchiv.de(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2021.Retrieved18 September2021.

- ^Niklas, Tomasz (23 August 2023). "Polscy jeńcy w Stalagu XX B Marienburg". In Grudziecka, Beata (ed.).Stalag XX B: historia nieopowiedziana(in Polish). Malbork: Muzeum Miasta Malborka. p. 29.ISBN978-83-950992-2-9.

- ^Gliński, Mirosław. "Podobozy i większe komanda zewnętrzne obozu Stutthof (1939–1945)".Stutthof. Zeszyty Muzeum(in Polish).3:165, 167–168, 175–176, 179.ISSN0137-5377.

- ^Voellner, Heinz (31 August 2020)."Bitwa o Gdańsk 1945".wiekdwudziesty.pl.Retrieved9 August2021.

- ^"Gdańsk.pl".3 March 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2006.

- ^Grzegorz Baziur, OBEPIPNKraków(2002)."Armia Czerwona na Pomorzu Gdańskim 1945–1947 (Red Army in Gdańsk Pomerania 1945–1947)".Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (Institute of National Remembrance Bulletin).7:35–38.

- ^Biskupski, Mieczysław B.The History of Poland.Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, p. 97.

- ^Tighe, Carl.Gdańsk: National Identity in the Polish-German Borderlands.London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 199.

- ^Loew, Peter Oliver (2011).Danzig – Biographie einer Stadt(in German). C.H. Beck. p. 232.ISBN978-3-406-60587-1.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^"Inka Monument".Europe Remembers.Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2021.Retrieved18 September2021.

- ^ab"Państwowy pogrzeb Żołnierzy Niezłomnych -" Inki "i" Zagończyka "".Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego.Archivedfrom the original on 18 September 2021.Retrieved18 September2021.

- ^abKubasiewicz, Izabela (2013). "Emigranci z Grecji w Polsce Ludowej. Wybrane aspekty z życia mniejszości". In Dworaczek, Kamil; Kamiński, Łukasz (eds.).Letnia Szkoła Historii Najnowszej 2012. Referaty(in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 114.

- ^Kozinska, Bogdana; Bingen, Dieter (2005).Die Schleifung – Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau historischer Bauten in Deutschland und Polen(in German). Deutsches Polen-Institut. p. 67.ISBN978-3-447-05096-8.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^Loew, Peter Oliver (2011).Danzig – Biographie einer Stadt(in German). C.H. Beck. p. 146.ISBN978-3-406-60587-1.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved17 October2020.

- ^Kalinowski, Konstanty; Bingen, Dieter (2005).Die Schleifung – Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau historischer Bauten in Deutschland und Polen(in German). Deutsches Polen-Institut. p. 89.ISBN978-3-447-05096-8.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^Friedrich, Jacek (2010).Neue Stadt in altem Glanz – Der Wiederaufbau Danzigs 1945–1960(in German). Böhlau. pp. 30, 40.ISBN978-3-412-20312-2.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved17 October2020.

- ^Czepczynski, Mariusz (2008).Cultural landscapes of post-socialist cities: representation of powers and needs.Ashgate publ. p. 82.ISBN978-0-7546-7022-3.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved17 October2020.

- ^Friedrich, Jacek (2010).Neue Stadt in altem Glanz – Der Wiederaufbau Danzigs 1945–1960(in German). Böhlau. pp. 34, 102.ISBN978-3-412-20312-2.Archivedfrom the original on 8 October 2021.Retrieved17 October2020.

- ^Barker, Colin (17 October 2005)."The rise of Solidarnosc".International Socialism.Retrieved10 December2022.

- ^ab"W Gdańsku otwarto Europejskie Centrum Solidarności"(in Polish). Onet.pl. 31 August 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 13 December 2015.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^Bednarz, Beata (9 July 2019)."Powódź w Gdańsku. 9 lipca 2001 r. gwałtowna ulewa zatopiła część miasta. 18 rocznica tragicznych wydarzeń [archiwalne zdjęcia]".Dziennik Bałtycki.Retrieved16 October2022.

- ^Olejarczyk, Piotr (9 July 2021)."Gdańsk. Mija 20 lat od tragicznej w skutkach powodzi [ZDJĘCIA]".Onet.pl.Retrieved16 October2022.

- ^"Italy's Mogherini and Poland's Tusk get top EU jobs".BBC. 30 August 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 31 August 2014.Retrieved8 August2015.

- ^"Gdansk mayor Pawel Adamowicz dies after being stabbed in heart on stage".CNN. 14 January 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2019.Retrieved14 January2019.

- ^"Mayor of Polish city dies after stabbing at charity event".msn. Archived fromthe originalon 15 January 2019.Retrieved16 April2019.

- ^"Polish city of Gdansk wins Princess of Asturias Award".Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2019.Retrieved19 October2019.

- ^"Report on the quality of life in European cities, 2023"(PDF).ec.europa.eu.Retrieved18 January2024.

- ^"Köppen climate classificationArchived14 February 2018 at theWayback Machine".Britannica.Retrieved 14 February 2018

- ^abcGdanskArchived6 November 2018 at theWayback Machine".Weatherbase.Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^"Średnia dobowa temperatura powietrza".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 3 December 2021.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Średnia minimalna temperatura powietrza".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Średnia maksymalna temperatura powietrza".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Miesięczna suma opadu".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Liczba dni z opadem >= 0,1 mm".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Średnia grubość pokrywy śnieżnej".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Liczba dni z pokrywą śnieżna > 0 cm".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Średnia suma usłonecznienia (h)".Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020(in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2022.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Gdańsk Średnie i sumy miesięczne".meteomodel.pl. 6 April 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 9 March 2020.Retrieved14 January2020.

- ^"Gdańsk, Poland – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast".Weather Atlas.Retrieved1 August2022.

- ^"Climate & Weather Averages in Gdańsk".Time and Date.Retrieved31 July2022.

- ^ab"Gdańsk – dobry klimat dla interesów. 8 biznesowych rzeczy, których nie wiedziałeś o Gdańsku".Business Insider.Onet.13 July 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2021.Retrieved31 October2021.

- ^"LOTOS Group History".lotos.pl.Grupa Lotos.Retrieved9 August2024.

- ^"Baltexpo International Maritime Fair and Conference 2023 is coming soon!".polandatsea.31 March 2023.Retrieved4 April2024.

- ^"BALTEXPO will return in 2025!".baltexpo.Retrieved4 April2024.

- ^"Forum Gdańsk. The new face of the city".pomorskie-prestige.eu.9 June 2018.Retrieved4 April2024.

- ^"Forum Gdańsk / SUD Polska".archdaily.ArchDaily.16 August 2019.Retrieved9 September2021.

- ^"Bezrobotni zarejestrowani i stopa bezrobocia. Stan w końcu lipca 2021 r."stat.gov.pl(in Polish).Retrieved4 April2024.

- ^"Główne i Stare Miasto Gdańsk".suerteprzewodnicy.pl(in Polish). 25 May 2023.Retrieved5 August2023.

- ^abcdeRichard Franks (15 November 2017)."Must-Visit Attractions in Gdańsk, Poland".theculturetrip.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Golden Gate, Gdańsk".Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. Main City Town Hall".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. Artus Court".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^Russell Sturgis; Arthur Lincoln Frothingham (1915).A history of architecture.Baker & Taylor. p.293.

- ^Paul Wagret; Helga S. B. Harrison (1964).Poland.Nagel. p. 302.Archivedfrom the original on 10 October 2021.Retrieved17 October2020.

- ^"Fontanna Neptuna w Gdańsku".suerteprzewodnicy.pl(in Polish). 16 December 2022.Retrieved5 August2023.

- ^"The New Jury House (The Gdańsk Hall)".Pomorskie.travel.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved1 May2020.

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. Golden House".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. Green Gate".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Olivia Star - The Skyscraper Center".skyscrapercenter.Retrieved30 April2023.

- ^ROBiDZ w Gdańsku."Kaplica Królewska w Gdańsku".wrotapomorza.pl(in Polish). Archived fromthe originalon 10 February 2015.Retrieved29 December2008.

- ^"Pomniki historii".

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. The Crane".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. Town Hall of the Old Town".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Classical Gdańsk. Mariacka Street".Archived fromthe originalon 2 December 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"HISTORIA PÓŁWYSPU WESTERPLATTE"(in Polish).Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Twierdza Wisłoujście - mało znana sąsiadka Westerplatte".onet.pl(in Polish). 24 December 2021.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Zoo Gdansk".Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Muzeum Narodowe w Gdańsku".culture.pl(in Polish).Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"Historical Museum of the City of Gdansk".Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^"The European Solidarity Centre".culture.pl.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^Alex Webber."Gdańsk rising: the cradle of the Second World War defies it past and embraces a bold future".thefirstnews.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^Snow, Georgia (3 September 2014)."Elizabethan playhouse in Poland to host work by Shakespeare's Globe".The Stage.Archivedfrom the original on 12 September 2014.Retrieved15 September2014.

- ^"Airport History".Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^ab"Nasza historia"(in Polish). Archived fromthe originalon 5 November 2022.Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^SKM Passenger Information, Maphttp:// skm.pkp.pl/Archived27 December 2014 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Wszystko na temat branży kolejowej: PKP, Intercity, przewozy regionalne, koleje mazowieckie, rozkłady jazdy PKP, Kolej".Rynek-kolejowy.pl.Retrieved29 July2018.

- ^"Pendolino z Trójmiasta do Warszawy. Więcej pytań niż odpowiedzi".trojmiasto.pl.30 July 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2014.Retrieved25 December2014.

- ^';Jeszcze szybciej z Warszawy do Gdańska,' Kurier Kolejowy 9 January 2015http:// kurierkolejowy.eu/aktualnosci/22716/Jeszcze-szybciej-z-Warszawy-do-Gdanska.htmlArchived10 January 2015 at theWayback Machine

- ^"PKM SA podpisała umowę na realizację tzw." bajpasu kartuskiego "z gdyńską firmą Torhamer".PKM(in Polish). 22 December 2020.

- ^Oleksy, Ewelina (21 June 2018). "W Gdańsku dzieci będą jeździć za darmo. Ale tylko z kartą".Naszemiasto.pl.

- ^"The port and the city".Retrieved2 December2022.

- ^Brancewicz, Michał (30 December 2019)."42 lata temu otwarto Obwodnicę Trójmiasta".trojmiasto.pl.Retrieved9 August2024.

- ^Mutler, Alison (12 October 2020)."Rail-2-Sea and Via Carpathia, the US-backed highway and rail links from the Baltic to the Black Sea".Universul.net.Archivedfrom the original on 10 November 2021.Retrieved13 July2021.

- ^Lewkowicz, Łukasz (2020)."The Three Seas Initiative as a new model of regional cooperation in Central Europe: A Polish perspective".UNISCI Journal.18(54): 177–194.doi:10.31439/UNISCI-101.Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022.Retrieved13 July2021.

- ^"The Story of Lechia Gdansk".24 April 2019.Retrieved2 December2022.