Geography of Wales

Map of Wales.Topographyabove 600 feet (182.88m) in pink;national parksin green. | |

| |

| Continent | Europe |

|---|---|

| Region | British Isles |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21,218 km2(8,192 sq mi) |

| Highest point | Snowdon (Welsh:Yr Wyddfa) |

| Longest river | River Severn (Welsh:Afon Hafren) |

| Largest lake | Lake Vyrnwy (Welsh:Llyn Efyrnwy) |

| Climate | Temperate |

| References | |

| [1][2] | |

Walesis acountrythat ispart oftheUnited Kingdomand whosephysical geographyis characterised by a variedcoastlineand a largelyuplandinterior. It isborderedbyEnglandto its east, theIrish Seato its north and west, and theBristol Channelto its south. It has a total area of 2,064,100 hectares (5,101,000 acres) and is about 170 mi (274 km) from north to south and at least 60 mi (97 km) wide. It comprises 8.35 percent of the land of the United Kingdom. It has a number of offshore islands, by far the largest of which isAnglesey.The mainland coastline, including Anglesey, is about 1,680 mi (2,704 km) in length. As of 2014, Wales had a population of about 3,092,000;Cardiffis the capital and largest city and is situated in the urbanised area ofSouth East Wales.

Wales has a complex geological history which has left it a largely mountainous country. The coastal plain is narrow in the north and west of the country but wider in the south, where theVale of Glamorganhas some of the best agricultural land. Exploitation of theSouth Wales Coalfieldduring theIndustrial Revolutionresulted in the development of an urban economy in the South Wales Valleys, and the expansion of the port cities ofNewport,Cardiff andSwanseafor the export ofcoal.The smallerNorth Wales Coalfieldwas also developed at this time, but elsewhere in the country, the landscape is rural and communities are small, the economy being largely dependent on agriculture and tourism. The climate is influenced by the proximity of the country to theAtlantic Oceanand the prevailing westerly winds; thus it tends to be mild, cloudy, wet and windy.

Physical geography

[edit]

Wales is located on the western side of central southernGreat Britain.To the north and west is theIrish Sea,and to the south is theBristol Channel.The English counties ofCheshire,Shropshire,HerefordshireandGloucestershirelie to the east.[3]Much of the border with England roughly follows the line of the ancient earthwork known asOffa's Dyke.[4]The large island ofAngleseylies off the northwest coast, separated from mainland Wales by theMenai Strait,and there are a number of smaller islands.[3]

Most of Wales is mountainous.Snowdonia(Welsh:Eryri) in the northwest has the highest mountains, withSnowdon(Yr Wyddfa) at 1,085 m (3,560 ft) being the highest peak. To the south of the main range lie theArenig Group,Cadair Idrisand theBerwyn Mountains.In the northeast of Wales, between theClwyd Valleyand the Dee Estuary, lies theClwydian Range.[3]The 14 (or possibly 15) peaks over 3,000 feet (914 m), all in Snowdonia, are known collectively as theWelsh 3000s.[5]

TheCambrian Mountainsrun from northeast to southwest and occupy most of the central part of the country. These are more rounded and undulating, clad in moorland and rough,tussocky grassland.In the south of the country are theBrecon Beaconsin central Powys, theBlack Mountains(Y Mynyddoedd Duon) spread across parts of Powys and Monmouthshire in southeast Wales and, confusingly,Black Mountain(Y Mynydd Du), which lies further west on the border between Carmarthenshire and Powys.[3]

The Welsh lowland zone consists of the north coastal plain, the island of Anglesey, part of theLlŷn Peninsula,a narrow strip of coast alongCardigan Bay,much ofPembrokeshireand southernCarmarthenshire,theGower Peninsulaand theVale of Glamorgan.[3]The main rivers are theRiver Dee,part of which forms the boundary between Wales and England, the River Clwyd and theRiver Conwy,which all flow northwards intoLiverpool Bayand the Irish Sea. Further round the coast, theRivers Mawddach,Dovey,Rheidol,YstwythandTeififlow westwards into Cardigan Bay, and the riversTowy,Taff,UskandWyeflow southwards into the Bristol Channel. Parts of theRiver Severnform the boundary between Wales and England.[3]

The length of the coast of mainland Wales is about 1,370 mi (2,205 km), and adding to this the coasts of the Isle of Anglesey andHoly Island,the total is about 1,680 mi (2,704 km).[6]Cardigan Bay is the largest bay in the country andBala Lake(Llyn Tegid) the largest lake[7]at 4.7 km2(1.8 sq mi). Other large lakes includeLlyn Trawsfynyddat 1.8 sq mi (4.7 km2),[8]Lake Vyrnwyat 1.7 sq mi (4.4 km2),[9]Llyn Brenigat 1.4 sq mi (3.6 km2),[10]Llyn Celynat 1.2 sq mi (3.1 km2)[11]andLlyn Alawat 1.2 sq mi (3.1 km2).[12]Bala Lake lies in aglacial valleyblocked by aterminal moraine,but the other lakes arereservoirscreated by impounding rivers, to provide drinking water, hydroelectric schemes or flood defences, and many are also used recreationally.[13]

Geology

[edit]

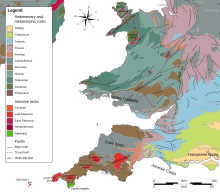

The geology of Wales is complex and varied. The earliestoutcroppingrocks are from thePrecambrianera, some 700Mya,and are found in Anglesey, the Llŷn peninsula, southwestern Pembrokeshire and in places near the English border. During theLower Palaeozoic,as seas periodically flooded the land and retreated again, thousands of metres ofsedimentaryandvolcanic rocksaccumulated in a marinebasinknown as theWelsh Basin.[14]Rocks found in a quarry near to the villageLlangynog,Carmarthenshire, in 1977 contain some of the Earth's oldest fossils which date from theEdiacaranperiod, 564 million years ago, when Wales was part of the micro-continentAvalonia.[15]

During the early and middleOrdovicianperiod (485 to 460 Mya), volcanic activity increased. One large volcanic system, which was centred around what is now Snowdon, emitted an estimated 60 cubic kilometres (14 cu mi) of debris. Another volcano formedRhobell Fawrnear Dolgellau. During this period, great accumulations of sand, gravel and mud were deposited further south in Wales, and these gradually consolidated. Some of the volcanic ash fell in the sea and formed great banks, where unstable masses sometimes slid into deeper water, creating submarineavalanches.This caused greatturbidityin the sea, after which the particles began to settle out according to particle size. Thestratathus formed are calledturbidites,and these are common in central Wales, being particularly obvious in the sea cliffs aroundAberystwyth.[14]

By the beginning of theDevonianperiod (420 Mya) the sea was retreating from the Welsh Basin as the land was thrust up by the collision of land masses, forming a new range of mountains, the Welsh Caledonides. The Old Red Sandstone represents debris from their erosion. Elsewhere the strata were compressed and deformed, and in places, the clay minerals recrystallised, developing a grain that allowed parallel cleavage, making it easy to split the rocks into thin flat sheets of stone known asslate.In the early part of theCarboniferousperiod, reinvasion of southern and northern parts of Wales by the sea resulted in depositions of limestone, and extensive swamps in South Wales gave rise to peat deposits and the eventual formation of coal measures. Erosion of nearby upland areas resulted in the formation of sandstones and mudstones in the later part of the period. Southwestern Wales, in particular, was affected by theVariscan orogeny,a period when continental collisions further south caused complexfoldingand fracturing of the strata.[14]

During thePermian,TriassicandJurassic(300 to 150 Mya), further episodes ofdesertification,subsidence and uplift occurred and Wales was alternately inundated by the sea and raised above it. By theCretaceous(140 to 70 Mya), Wales was permanently above sea level and in thePleistocene(2.5 Mya to recent), it underwent several exceptionally cold periods, theice ages.The mountains we see today largely assumed their present shape during the last ice age, theDevensian glaciation.[14]

In the mid 19th century, two prominentgeologists,Roderick MurchisonandAdam Sedgwick,used their studies of thegeology of Walesto establish certain principles ofstratigraphyandpalaeontology.From the Latin name for Wales,Cambria(derived fromCymru), was derived the name of the earliestgeologicalperiod of the Paleozoic era, theCambrian.After much dispute, the next two periods of the Paleozoic era, theOrdovicianandSilurian,were named after pre-Roman Celtic tribes of Wales, theOrdovicesandSilures.[16]

Climate

[edit]Wales has amaritime climate,the predominant winds being southwesterlies and westerlies blowing in from theAtlantic Ocean.This means that the weather in Wales is in general mild, cloudy, wet and windy. The country's wide geographic variations cause localised differences in amounts of sunshine, rainfall and temperature. Rainfall in Wales varies widely, with the highest average annual totals in Snowdonia and the Brecon Beacons, and the lowest near the coast and in the east, close to the English border. Throughout Wales, the winter months are significantly wetter than the summer ones. Snow is comparatively rare near sea level in Wales, but much more frequent over the hills, and the uplands experience harsher conditions in winter than the more low-lying parts.[17]

The mean annual temperatures in Wales are about 11 °C (52 °F) on the coast and 9.5 °C (49 °F) in low-lying inland areas. It becomes cooler at higher altitudes, with a mean decrease in annual temperatures of approximately 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) for each 100 metres (330 feet) of increased altitude. Consequently, the higher parts of Snowdonia experience mean annual temperatures of 5 °C (41 °F).[17]At nights, the coldest conditions occur when there is little wind and no cloud cover, especially when the ground is snow-clad; the lowest temperature recorded in Wales was in conditions of this sort atRhayaderon New Year's Day, 1940, when the temperature fell to −23.3 °C (−9.9 °F). Occasionally, the coastal area of North Wales experiences some of the warmest winter conditions in the United Kingdom, with temperatures up to 18 °C (64 °F); these result from aFoehn wind,a south-westerly airflow warming up as it descends from the mountains of Snowdonia.[17]

Rainfall in Wales is mostly as a result of the arrival of Atlanticlow pressure systemsand is heaviest between October and January over the whole country. The driest months are usually April, May and June, and Wales experiences fewer summer thunderstorms than England. Rainfall varies across the country with the highest records being from the greatest elevations. Snowdonia experiences total annual rainfalls exceeding 3,000 mm (118 in) whereas coastal regions of Wales and the English border may have less than 1,000 mm (39 in). The combination of mountainous areas and Atlantic lows can produce large quantities of rain and sometimes results in flooding.[17]The amount of snowfall varies with altitude and enormously from year to year. In the lowlands, the number of days with lying snow may vary from zero to thirty or more, with an average of about twenty in Snowdonia.[17]

Wales is one of the windier parts of the United Kingdom. The strongest winds are usually associated with Atlantic depressions; as one of these arrives, the winds usually start in the southwest, before veering to the west and then to the northwest as the system passes by. The southwest of Pembrokeshire experiences the most gale-force winds. The highest wind speed ever recorded in Wales at a lowland site was gusts of 108 knots (200 km/h; 124 mph) atRhoose,in the Vale of Glamorgan, on 28 October 1989.[17]

Land use

[edit]

The total terrestrial surface[clarification needed]of Wales is 2,064,100 hectares (5,101,000 acres). Thearea of land used for agriculture and forestryin the country in 2013 was 1,712,845 hectares (4,232,530 acres). Of this 79,461 hectares (196,350 acres) was used for arable cropping and fallow, 1,449 hectares (3,580 acres) for horticulture, and 1,405,156 hectares (3,472,220 acres) was used for grazing. Woodland occupied 63,366 hectares (156,580 acres) and 10,126 hectares (25,020 acres) was unclassified land. In addition, there were 180,305 hectares (445,540 acres) of common rough grazing, giving a total area of all the land used for agriculture purposes, including common land, of 1,739,863 hectares (4,299,300 acres).[18]

In order of area planted, the arable crops grown in Wales were: foods for stock-feeding, spring barley, wheat, maize, winter barley, other cereals for combining, oilseed rape, potatoes and other crops. The grassland was predominantly permanent pasture, with only 10% of the grassland being under five years old.[18]Compared with other parts of the United Kingdom, Wales has the smallest percentage of arable land (6%), and a considerably smaller area of rough grazing and hill land than Scotland (27% against 62%).[19]

Natural resources

[edit]Vast quantities of coal were mined in Wales during theIndustrial Revolutionand the earlier part of the twentieth century, after which coal stocks dwindled and the remaining pits became uneconomical as foreign coal became available at low prices. The last deep pit in Wales closed in 2008.[20]

Ironstoneoutcrops along the northern edge of the South Wales Coalfield were extensively worked for the production of iron and were important in the initiation of the Industrial Revolution in South Wales.[21]

Lead,silverand to a lesser extentzincwere mined in the upland areas of the riversYstwythandRheidoland in the headwaters of theRiver Severnfor centuries and smaller deposits were also mined atPentre Halkynin Flintshire during the Roman occupation of Britain. Copperwas a major export fromParys MountainonAngleseywhich was, at its height, the largest copper mine in the world.

Slate quarrying has been a major industry in North Wales. TheCilgwyn Quarrywas being worked in the 12th century, but laterBlaenau Ffestiniogbecame the centre of production.[22]

With its mountainous terrain and ample rainfall, water is one of Wales' most abundant resources. The country has many man-madereservoirsand exports water to England as well as generating power throughhydroelectric schemes.

Wind is another resource that Wales has in abundance.Gwynt y Môris one of severaloffshore wind farmsoff the coast of the North Wales mainland and Anglesey, and is the second largest such wind farm in the world.[24]

Political geography

[edit]Border between Wales and England

[edit]The modernborder between Wales and Englandwas largely defined by theLaws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542,based on the boundaries ofmedievalMarcher lordships.According to the Welsh historianJohn Davies:[25]

Thus was created the border between Wales and England, a border which has survived until today. It did not follow the old line of Offa's Dyke nor the eastern boundary of the Welsh dioceses; it excluded districts such as Oswestry and Ewias, where the Welsh language would continue to be spoken for centuries, districts which it would not be wholly fanciful to consider asCambria irredenta.Yet, as the purpose of the statute was to incorporate Wales into England, the location of the Welsh border was irrelevant to the purposes of its framers.

The boundary has never been confirmed by referendum or reviewed by aBoundary Commission.The boundary line very roughly follows Offa's Dyke from south to north as far as a point about 40 miles (64 km) from the northern coast, but then swings further east.[26]It has a number of anomalies, but some were ironed out by theCounties (Detached Parts) Act 1844.[27]For instance, it separatesKnightonfrom its railway station,[28]and divides the village ofLlanymynechwhere a pub straddles the line.[29]

Local government

[edit]Wales is divided into 22unitary authorities,which are responsible for the provision of all local government services, including education, social work, environmental and road services. Below these in some areas there arecommunity councils,which cover specific areas within a council area. The unitary authority areas are known as "principal areas".[30]The King appointsLords Lieutenantto represent him in the eightpreserved counties of Wales.[31]

In theOffice for National StatisticsArea Classification, local authorities are clustered into groups based in the six maincensusdimensions (demographic, household composition, housing, socio-economic, employment and industry sector). Most of the local authorities in mid and west Wales are classified as part of the 'Coastal and Countryside' supergroup. Most of the south Wales authorities,FlintshireandWrexhamare in the 'Mining and Manufacturing' supergroup;Cardiffis part of the 'Cities and Services' supergroup and the Vale of Glamorgan is part of 'Prospering UK'.[32]

Social geography

[edit]A number of historians ofWaleshave questioned the notion of a single, cohesive Welsh identity. For example, in 1921,Alfred Zimmern,the inaugural professor of international relations at theUniversity of Wales, Aberystwyth,argued that there was "not one Wales, but three": archetypal 'Welsh Wales', industrial or 'American Wales', and upper-class 'English Wales'. Each represented different parts of the country and different traditions.[33]In 1985, political analyst Dennis Balsom proposed a similar 'Three Wales model'. Balsom's regions were the Welsh-speaking heartland of the north and west,Y Fro Gymraeg;a consciously Welsh but not Welsh-speaking 'Welsh Wales' in theSouth Wales Valleysand a more ambivalent 'British Wales' making up the remainder, largely in the east and along the south coast.[34]The division reflects, broadly, the areas wherePlaid Cymru,Labour,and theConservativesandLiberal Democratsrespectively enjoyed the most political support.[citation needed]

Topographyhas traditionally limited the integration between North and South Wales, with the two halves virtually functioning as separate economic and social units in the preindustrial era, with successive British Government transport policy doing little to rectify it.[35]Today, the main road and rail links run east-west, although there was once a north-south rail link that pressure groups are attempting to reinstate.[36]By the interwar years, industry in South Wales was increasingly linked toAvonsideand theEnglish Midlands,and that in north Wales toMerseyside.[37]

Liverpool was often called "the capital of north Wales" in the late 19th and early 20th century. With 20,000 Welsh-born people living on either side of the Mersey in 1901, the city had an array of Welsh chapels and cultural institutions; hosted theNational Eisteddfodin 1884, 1900 and 1929 and gave rise to several leading figures in Welsh life in the 20th century.[38]TheLiverpool Daily Postbecame, effectively, the daily newspaper for north Wales.[39]The decline of Liverpool after the Second World War and changing patterns of Welsh migration, caused the Welsh presence to diminish. In the 1960s, the flooding of theTryweryn Valleyto provide the city with water soured relations with many people in Wales.[38]

The North Welsh are sometimes referred to, inWenglish,asGogs(from the Welshgogledd,"north" ) and the south Welsh asHwntws(fromtu hwntroughly meaning 'far away over there' or 'beyond'). There are differences in the Welsh vocabulary between the north and south; for instance, the south Welsh word fornowisnawrwhereas the north Welsh isrŵan.[citation needed]

The more urbanised south, containing cities such asCardiff,NewportandSwansea,was historically home to the coal and steel industries. It contrasts with the mostly rural north, where agriculture and slate quarrying were the main industries. Although theM4 corridorbrings wealth into South Wales, particularly Cardiff, there is no pronouncedeconomic divide between north and southunlike in England; there is, for example, a high level of poverty in the postindustrialSouth Wales Valleys.[citation needed]

Demography

[edit]

The estimated population of Wales in 2019 was about 3,152,879, an increase of 14,248 on the previous year.[40]The main population and industrial areas in Wales are inSouth Wales,specifically Cardiff,SwanseaandNewportand the adjoiningSouth Wales Valleys.Cardiff is the capital city and had a population of around 346,000 at the 2011 census. This was followed by the unitary authorities of Swansea (239,000), Rhondda Cynon Taf (234,400), Carmarthenshire (183,800), Caerphilly (178,800), Flintshire (152,500), Newport (145,700), Neath Port Talbot (139,800), Bridgend (139,200) and Wrexham (134,800).[41]Cardiff was the most heavily populated area in Wales with 2,482 people per square kilometre (6,428 per sq mile) while Powys had just 26.[42]

A high proportion of the Welsh population lives in smaller settlements: nearly 20% live in villages of less than 1,500 persons compared with 10% in England. Wales also has a relatively low proportion of its population in large settlements: only 26% live in urban areas with a population over 100,000; in comparison, nearly 40% of the English population live in urban areas larger than the largest in Wales. Another feature of the settlement pattern in Wales is the share of the population living in the sparsest rural areas: 15% compared with only 1.5% in England.[43]

Communications

[edit]Communications within Wales are influenced by the topography and the mountainous nature of the country: the main rail and road routes between South and North Wales loop to the east and pass largely through England. The only motorway corridor in Wales is theM4 motorwayfrom London to South Wales, entering the country over theSecond Severn Crossing,passing close to Newport, Cardiff and Swansea and extending as far west as thePont Abraham servicesbefore continuing northwest as theA48toCarmarthen.TheM48 motorwayparallels the M4 betweenAustandMagorviaChepstow.TheA40is a majortrunk roadconnecting London toFishguardviaBreconand Carmarthen.[44]TheA487coast road links Cardigan with Aberystwyth, and theA44links Aberystwyth with Rhayader,LeominsterandWorcester.[45]The main trunk road in North Wales is theA55dual carriagewayroad from Chester pastSt AsaphandAbergele,continuing along the coast toBangor,crossing Anglesey and terminating atHolyhead.[46]TheA483runs from Swansea to Chester passingLlandovery,Llandrindod Wells,Oswestry(in England) andWrexham.

TheSouth Wales Main LinelinksLondon Paddingtonwith Swansea, entering Wales through theSevern Tunnel.Other main line services from the Midlands and the North of England join this at Newport. Branch lines serve the South Wales Valleys, Barry, and destinations beyond Swansea which include the ferry terminals at Fishguard and Pembroke Dock. TheHeart of Wales LinelinksLlanelliwithCraven Armsin Shropshire.[47]TheCambrian Linecrosses the centre of Wales, with trains fromShrewsburytoWelshpool,Aberystwyth andPwllheli.[48]TheNorth Wales Coast LinelinksCreweandChestertoBangorandHolyhead,from where there is a ferry service to Ireland. Passengers can change atShottonfor theBorderlands Line,which links Wrexham withBidstonon theWirral Peninsula,and at Conwy for theConwy Valley LinetoBlaenau Festiniog.[49]TheShrewsbury–Chester linebetween Chester and Shrewsbury in England, passes through Wrexham, Chirk and Ruabon in Wales.

Cardiff Airportis the only airport in Wales which offers international scheduled flights. Destinations available include other parts of the United Kingdom, Ireland and parts of continental Europe. The airport is also used for charter flights on a seasonal basis. In 2018, around 1.6 million passengers used the airport.[50]Several ferry services operate between Welsh ports and Ireland: Holyhead toDublin;Fishguard to Rosslare;[51]Pembroke Dock to Rosslare;[52]and Swansea toCork.[53]

Protected areas

[edit]

Wales has three designatednational parks.Snowdonia National Park in northwestern Wales was established in 1951 as the thirdnational park in Britain,following thePeak Districtand theLake District.It covers 827 square miles (2,140 km2) of the mountains of Snowdonia and has 37 miles (60 km) of coastline.[54][55]ThePembrokeshire Coast National Parkwas established the following year to protect the spectacular coastal scenery of West Wales. It includesCaldey Island,theDaugleddauestuary and thePreseli Hills,as well as the entire length of thePembrokeshire Coast Path.[56]TheBrecon Beacons National Parkwas established five years later and extends across the southern part of Powys, the northwestern part of Monmouthshire, parts of eastern Carmarthenshire and the northern parts of several South Wales Valleys county boroughs. In each case, the national park authority acts as aspecial purpose local authorityand exercises planning control over residential and industrial development in the park. The authorities have a duty to conserve the natural beauty of the area, and to promote opportunities for members of the public to enjoy and appreciate the park's special qualities.[57]

Wales also has fiveAreas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.These differ from National Parks in that the local authorities have a duty to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the landscape but do not have an obligation to promote the enjoyment of the public. Partnerships established to administer AONBs do not have control over planning, responsibility for which remains with the constituent local authorities.[58]In 1956, the Gower Peninsula became the first designated AONB in Britain.[59]Other AONBs are: the coast of Anglesey; the Llŷn Peninsula;[60]theClwydian Range and Dee Valley;[61]and theWye Valley,part of which is in England.[62]

Wales has many waterfalls, including some of the most striking in the United Kingdom. One such is the 240 ft (73 m)Pistyll Rhaeadrnear the village ofLlanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant.It is formed as a mountain stream drops over a cliff and changes character to a lowland river, theAfon Rhaeadr.The site was designated by theCountryside Council for Walesas the 1000thSite of Special Scientific Interestin Wales, because of its importance to an understanding of Welshgeomorphology.The 19th-centuryEnglish authorGeorge Borrowremarked of the waterfall, "I never saw water falling so gracefully, so much like thin, beautiful threads, as here."[63]

See also

[edit]Wales

[edit]- Regions of Wales

- Geology of Wales

- Coastline of Wales

- List of Blue Flag Beaches of Wales

- List of islands of Wales

- Little England beyond Wales

Other

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"Standard Area Measurements for Administrative Areas (December 2023) in the UK".Open Geography Portal.Office for National Statistics. 31 May 2024.Retrieved7 June2024.

- ^"A Beginners Guide to UK Geography (2023)".Open Geography Portal.Office for National Statistics. 24 August 2023.Retrieved9 December2023.

- ^abcdefPhilip's (1994).Atlas of the World.Reed International. pp. 16–17.ISBN0-540-05831-9.

- ^Else, David; Bardwell, Sandra; Dixon, Belinda; Dragicevich, Peter (2007).Walking in Britain.Lonely Planet. p. 333.ISBN978-1-74104-202-3.

- ^"The Welsh 3000s Challenge".The Welsh 3000s.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^"How long is the UK coastline?".Cartopics.The British Cartographic Society. Archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2012.Retrieved25 April2016.

- ^"Bala Lake".The Snowdonia National Park.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^"History".Traws Lake.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^"Lake Vyrnwy".1891 The Practical Engineer.Technical Publishing Company.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^"Llyn Brenig Reservoir and Visitor Centre".AboutBritain.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^"Llyn Celyn".The Snowdonia National Park.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^"Llyn Alaw".Anglesey Visitor.Retrieved12 April2016.

- ^Patmore, John Allan (1971).Land and Leisure in England & Wales.Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 262.ISBN978-0-8386-1024-4.

- ^abcd"Environmental Change and Mineral Formation in Wales".Wales Underground.Retrieved13 April2016.

- ^Thomas, Gavin (21 January 2024)."Earth's earliest creatures dated from Welsh rocks".BBC News.Archived fromthe originalon 21 January 2024.Retrieved21 January2024.

- ^Jones, Alyn."What's in a name? Celtic Connections".The Edinburgh Geologist: Issue No. 35.Edinburgh Geological Society.Retrieved24 April2016.

- ^abcdef"Wales: Climate".Met Office.Retrieved22 April2016.

- ^ab"Land use".Climate Change Commission for Wales. p. 59.Retrieved22 April2016.

- ^"A review of the Beef Sector in Wales".Meat Promotion Wales. 27 November 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 15 April 2016.Retrieved22 April2016.

- ^"Coal mine closes with celebration".BBC News.25 January 2008.Retrieved22 April2016.

- ^"Blaenavon World Heritage Site".Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^Lindsay, Jean (1974).A History of the North Wales Slate Industry.David and Charles. p. 314.ISBN0-7153-6264-X.

- ^"Dinorwig Power Station".Mitsui & Co., Ltd. Archived fromthe originalon 12 May 2016.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^Denholm-Hall, Rupert (18 June 2015)."World's second largest offshore wind farm opens off coast of Wales".Wales Onlone.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^Davies, John (1993).A History of Wales.Penguin.ISBN0-14-028475-3.

- ^"The coming of the Tudors and the Act of Union (part 2)".Guide to Welsh History.BBC.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844".National Archives.UK Government.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Knighton Railway Station".Show me Mid Wales.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Llanymynech location".The Church of England. Archived fromthe originalon 6 May 2016.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Local Government (Wales) Act 1994".The National Archives.legislation,gov.uk.Retrieved22 April2016.

- ^"Clwyd: County history".High Sheriff's Association of England and Wales. 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2016.Retrieved21 April2016.

- ^"NS 2001 Area Classification for Local Authorities".Archived fromthe originalon 9 June 2009.Retrieved20 December2009.

- ^ Williams, Chris(Winter 2003–2004)."A post national Wales"(PDF).Agenda.Institute of Welsh Affairs. pp. 2–5.Archived(PDF)from the original on 4 September 2017.Retrieved3 September2017.

- ^Osmond, John (2002). "Welsh Civil Identity in the Twenty-First Century". In David C. Harvey; Rhys Jones; Neil McInroy; Christine Milligan (eds.).Celtic Geographies: Old culture, new times.London: Routledge. pp.80–82.ISBN0-415-22396-2.

- ^Malcolm Falkus; John Gillingham, eds. (1987).Historical Atlas of Britain.Kingfisher. p. 112.ISBN0-86272-295-0.

- ^"The Wales Transport Strategy"(PDF).Welsh Assembly Government. 2008. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 14 December 2008.Retrieved18 March2010.

- ^Morgan, Kenneth O.(1982).Rebirth of a nation: Wales 1880-1980.Oxford University Press. p.245.ISBN0-19-821760-9.

- ^abJohn Davies; Nigel Jenkins; Menna Baines; Peredur I. Lynch (2008).The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales.Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 469.ISBN978-0-7083-1953-6.

- ^Morgan, Kenneth O. (1982).Rebirth of a nation: Wales 1880-1980.Oxford University Press. pp.6–7.ISBN0-19-821760-9.

- ^"National level population estimates by year, age and UK country".statswales.gov.wales.Retrieved7 August2020.

- ^"Population change, 2001-2011".2011 Census: Population and Household Estimates for Wales, March 2011.Office for National Statistics.Retrieved24 April2016.

- ^Blake, Aled (8 August 2013)."UK population soars - but Wales still home to regions of emptiness".Wales Online.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^Welsh Assembly Government (2005).Rural Development Plan for Wales, 2007 to 2013: The Strategic Approach.Welsh Assembly Government. pp. 61–63.ISBN0-7504-9757-2.

- ^Concise Road Atlas: Britain.AA Publishing. 2015. pp. 24–27.ISBN978-0-7495-7743-8.

- ^Concise Road Atlas: Britain.AA Publishing. 2015. pp. 36–39.ISBN978-0-7495-7743-8.

- ^Concise Road Atlas: Britain.AA Publishing. 2015. pp. 47–55.ISBN978-0-7495-7743-8.

- ^Williams, Sally (29 March 2013)."Heart of Wales railway line in danger".Wales Online.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^Jenkins, Stanley C.; Loader, Martin (2015).The Great Western Railway: Shrewsbury to Pwllheli Vol. 5.Amberley Publishing Limited. pp. 15–16.ISBN978-1-4456-4299-4.

- ^"Crewe to Holyhead".North Wales Coast Railway. 2012.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^seneddresearch (5 March 2020)."Cardiff Airport – How many people are checking in?".IN BRIEF.Retrieved7 August2020.

- ^"Ferries to Ireland".Stena Line.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Pembroke / Rosslare".Irish Ferries.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Cork to Swansea Ferry".Cork Ferries.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^Culliford, Alison (24 July 1999)."National Parks: The complete guide to Britain's national parks".The Independent.

- ^"Our national parks".MSN.Archived fromthe originalon 2 October 2011.

- ^"Pembrokeshire Coast National Park".Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"About us".National Parks. Archived fromthe originalon 16 April 2016.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Natural England's statutory duties and powers".Natural England.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Gower Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty".City and County of Swansea.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Llŷn Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty".Gwynedd County Council.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty".Denbighshire Countryside Services.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty".Joint Advisory Committee.Retrieved23 April2016.

- ^"Waterfall, 1000th on protected list".BBC News.22 May 2000.Retrieved23 April2016.