Germanic languages

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2019) |

| Germanic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Worldwide, principally Northern, Western and Central Europe, theAmericas(Anglo-America,Caribbean NetherlandsandSuriname),Southern Africa,SouthandSoutheast Asia,Oceania |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Germanic |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2/5 | gem |

| Linguasphere | 52- (phylozone) |

| Glottolog | germ1287 |

European Germanic languages | |

World map showing countries where a Germanic language is the primary or official language Countries where thefirst languageof the majority of the population is a Germanic language

Countries or regions where a Germanic language is an official language but not aprimary language

Countries or regions where a Germanic language has no official status but is notable, i.e. used in some areas of life and/or spoken among a local minority | |

| Part ofa serieson |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

TheGermanic languagesare a branch of theIndo-Europeanlanguage familyspoken natively by a population of about 515 million people[nb 1]mainly inEurope,North America,Oceania,andSouthern Africa.The most widely spoken Germanic language,English,is also the world's mostwidely spoken languagewith an estimated 2 billion speakers. All Germanic languages are derived fromProto-Germanic,spoken inIron AgeScandinavia,Iron Age Northern Germany[2]and along theNorth Seaand Baltic coasts.[3]

TheWest Germanic languagesinclude the three most widely spoken Germanic languages:Englishwith around 360–400 million native speakers;[4][nb 2]German,with over 100 million native speakers;[5]andDutch,with 24 million native speakers. Other West Germanic languages includeAfrikaans,an offshoot of Dutch originating from theAfrikanersofSouth Africa,with over 7.1 million native speakers;[6]Low German,considered a separate collection ofunstandardizeddialects, with roughly 4.35–7.15 million native speakers and probably 6.7–10 million people who can understand it[7][8][9](at least 2.2 million inGermany(2016)[8]and 2.15 million in the Netherlands (2003));[10][7]Yiddish,once used by approximately 13 millionJewsin pre-World War IIEurope,[11]now with approximately 1.5 million native speakers;Scots,with 1.5 million native speakers;Limburgish varietieswith roughly 1.3 million speakers along theDutch–Belgian–Germanborder; and theFrisian languageswith over 500,000 native speakers in the Netherlands and Germany.

The largestNorth Germanic languagesareSwedish,Danish,andNorwegian,which are in part mutually intelligible and have a combined total of about 20 million native speakers in theNordic countriesand an additional five million second language speakers; since the Middle Ages, however, these languages have been strongly influenced byMiddle Low German,a West Germanic language, and Low German words account for about 30–60% of their vocabularies according to various estimates. Other extant North Germanic languages areFaroese,Icelandic,andElfdalian,which are more conservative languages with no significant Low German influence, more complex grammar and limited mutual intelligibility with other North Germanic languages today.[12]

TheEast Germanic branchincludedGothic,Burgundian,andVandalic,all of which are now extinct. The last to die off wasCrimean Gothic,spoken until the late 18th century in some isolated areas ofCrimea.[13]

TheSILEthnologuelists 48 different living Germanic languages, 41 of which belong to the Western branch and six to the Northern branch; it placesRiograndenser Hunsrückisch Germanin neither of the categories, but it is often considered a German dialect by linguists.[14]The total number of Germanic languages throughout history is unknown as some of them, especially the East Germanic languages, disappeared during or after theMigration Period.Some of the West Germanic languages also did not survive past the Migration Period, includingLombardic.As a result ofWorld War IIand subsequentmass expulsion of Germans,the German languagesuffereda significant loss ofSprachraum,as well as moribundity and extinction of several of its dialects. In the 21st century, German dialects are dying out[nb 3]asStandard Germangains primacy.[15]

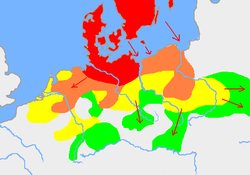

The common ancestor of all of the languages in this branch is called Proto-Germanic, also known as Common Germanic, which was spoken in about the middle of the 1st millennium BC inIron Age Scandinavia.Proto-Germanic, along with all of its descendants, notably has a number of unique linguistic features, most famously theconsonantchange known as "Grimm's law."Early varieties of Germanic entered history when theGermanic tribesmoved south fromScandinaviain the 2nd century BC to settle in the area of today's northern Germany and southern Denmark.

Modern status

[edit]

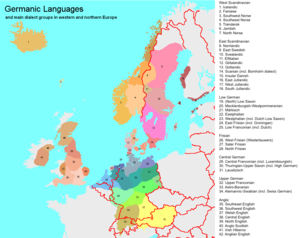

North Germanic languagesWest Germanic languagesDots indicate areas where it is common for native non-Germanic speakers to also speak a neighbouring Germanic language, lines indicate areas where it is common for native Germanic speakers to also speak a non-Germanic or other neighbouring Germanic language.

West Germanic languages

[edit]English is anofficial languageofBelize,Canada, Nigeria,Falkland Islands,Saint Helena,Malta,New Zealand, Ireland, South Africa, Philippines, Jamaica,Dominica,Guyana,Trinidad and Tobago,American Samoa,Palau,St. Lucia,Grenada,Barbados,St. Vincent and the Grenadines,Puerto Rico,Guam,Hong Kong, Singapore, Pakistan, India,Papua New Guinea,Namibia,Vanuatu,theSolomon Islandsand former British colonies in Asia, Africa and Oceania. Furthermore, it is thede factolanguage of the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia, as well as a recognized language inNicaragua[16]and Malaysia.

German is a language of Austria, Belgium, Germany,Liechtenstein,Luxembourgand Switzerland; it also has regional status in Italy, Poland, Namibia and Denmark. German also continues to be spoken as a minority language byimmigrant communitiesin North America, South America, Central America, Mexico and Australia. A German dialect,Pennsylvania Dutch,is still used among various populations in the American state ofPennsylvaniain daily life. A group of Alemannic German dialects commonly referred to asAlsatian[17][18]is spoken inAlsace,part of modern France.

Dutch is an official language ofAruba,Belgium,Curaçao,the Netherlands,Sint Maarten,andSuriname.[19]The Netherlands alsocolonizedIndonesia,but Dutch was scrapped as an official language afterIndonesian independence.Today, it is only used by older or traditionally educated people. Dutch was until 1983 an official language in South Africa but evolved into and was replaced byAfrikaans,apartially mutually intelligible[20]daughter languageof Dutch.

Afrikaans is one of the 11official languages in South Africaand is alingua francaof Namibia. It is used in otherSouthern Africannations, as well.

Low Germanis a collection of very diverse dialects spoken in the northeast of the Netherlands and northern Germany. Some dialects likeEast Pomeranianhave been imported to South America.[21]

Scots is spoken inLowlandScotland and parts ofUlster(where the local dialect is known asUlster Scots).[22]

Frisianis spoken among half a million people who live on the southern fringes of theNorth Seain the Netherlands and Germany.

Luxembourgish is aMoselle Franconiandialect that is spoken mainly in theGrand Duchy of Luxembourg,where it is considered to be an official language.[23]Similar varieties of Moselle Franconian are spoken in small parts of Belgium, France, and Germany.

Yiddish, once a native language of some 11 to 13 million people, remains in use by some 1.5 million speakers in Jewish communities around the world, mainly in North America, Europe, Israel, and other regions withJewish populations.[11]

Limburgishvarietiesare spoken in theLimburgandRhinelandregions, along the Dutch–Belgian–German border.

North Germanic languages

[edit]In addition to being the official language in Sweden,Swedishis also spoken natively by theSwedish-speaking minorityin Finland, which is a large part of the populationalong the coast of western and southernFinland. Swedish is also one of the two official languages in Finland, along withFinnish,and the only official language inÅland.Swedish is also spoken by some people in Estonia.[24]

Danishis an official language of Denmark and in its overseas territory of theFaroe Islands,and it is alingua francaand language of education in its other overseas territory ofGreenland,where it was one of the official languages until 2009. Danish, a locally recognized minority language, is also natively spoken by the Danish minority in the German state ofSchleswig-Holstein.

Norwegianis the official language of Norway (bothBokmålandNynorsk). Norwegian is also the official language in the overseas territories of Norway such asSvalbard,Jan Mayen,Bouvet island,Queen Maud Land,andPeter I island.

Icelandicis the official language ofIceland.

Faroeseis the official language of the Faroe Islands, and is also spoken by some people in Denmark.

Statistics

[edit]Germanic languages by share (West Germanic in yellow-red shades and North Germanic in blue shades):[nb 4]

| Language | Native speakers (millions)[nb 5] |

|---|---|

| English | 360–400[4] |

| German | 100[25][nb 6] |

| Dutch | 24[26] |

| Swedish | 11.1[27] |

| Afrikaans | 8.1[28][unreliable source] |

| Danish | 5.5[29] |

| Norwegian | 5.3[30] |

| Low German | 3.8[31] |

| Yiddish | 1.5[32] |

| Scots | 1.5[33] |

| Frisian languages | 0.5[34] |

| Luxembourgish | 0.4[35] |

| Icelandic | 0.3[36] |

| Faroese | 0.07[37] |

| Other Germanic languages | 0.01[nb 7] |

| Total | est. 515[nb 8] |

History

[edit]

All Germanic languages are thought to be descended from a hypotheticalProto-Germanic,united by subjection to the sound shifts ofGrimm's lawandVerner's law.[40]These probably took place during thePre-Roman Iron Ageof Northern Europe fromc. 500 BC.Proto-Germanic itself was likely spoken afterc. 500 BC,[41]andProto-Norsefrom the 2nd century AD and later is still quite close to reconstructed Proto-Germanic, but other common innovations separating Germanic fromProto-Indo-Europeansuggest a common history of pre-Proto-Germanic speakers throughout theNordic Bronze Age.

From the time of their earliest attestation, the Germanic varieties are divided into three groups:West,East,andNorthGermanic. Their exact relation is difficult to determine from the sparse evidence of runic inscriptions.

The western group would have formed in the lateJastorf culture,and the eastern group may be derived from the 1st-centuryvarietyofGotland,leaving southern Sweden as the original location of the northern group. The earliest period ofElder Futhark(2nd to 4th centuries) predates the division in regional script variants, and linguistically essentially still reflects theCommon Germanicstage. TheVimose inscriptionsinclude some of the oldest datable Germanic inscriptions, starting inc. 160 AD.

The earliest coherent Germanic text preserved is the 4th-centuryGothictranslation of theNew TestamentbyUlfilas.Early testimonies of West Germanic are inOld Frankish/Old Dutch(the 5th-centuryBergakker inscription),Old High German(scattered words and sentences 6th century and coherent texts 9th century), andOld English(oldest texts 650, coherent texts 10th century). North Germanic is only attested in scattered runic inscriptions, asProto-Norse,until it evolves intoOld Norseby about 800.

Longer runic inscriptions survive from the 8th and 9th centuries (Eggjum stone,Rök stone), longer texts in the Latin Alpha bet survive from the 12th century (Íslendingabók), and someskaldic poetrydates back to as early as the 9th century.

By about the 10th century, the varieties had diverged enough to makemutual intelligibilitydifficult. The linguistic contact of theVikingsettlers of theDanelawwith theAnglo-Saxonsleft traces in the English language and is suspected to have facilitated the collapse of Old English grammar that, combined with the influx ofRomanceOld Frenchvocabulary after theNorman Conquest,resulted inMiddle Englishfrom the 12th century.

The East Germanic languages were marginalized from the end of the Migration Period. TheBurgundians,Goths,andVandalsbecame linguistically assimilated by their respective neighbors by about the 7th century, with onlyCrimean Gothiclingering on until the 18th century.

During the early Middle Ages, the West Germanic languages were separated by the insular development of Middle English on one hand and by theHigh German consonant shifton the continent on the other, resulting inUpper GermanandLow Saxon,with graded intermediateCentral Germanvarieties. By early modern times, the span had extended into considerable differences, ranging fromHighest Alemannicin the South toNorthern Low Saxonin the North, and, although both extremes are considered German, they are hardly mutually intelligible. The southernmost varieties had completed the second sound shift, while the northern varieties remained unaffected by the consonant shift.

The North Germanic languages, on the other hand, remained unified until well past 1000 AD, and in fact the mainland Scandinavian languages still largely retain mutual intelligibility into modern times. The main split in these languages is between the mainland languages and the island languages to the west, especiallyIcelandic,which has maintained the grammar of Old Norse virtually unchanged, while the mainland languages have diverged greatly.

Distinctive characteristics

[edit]Germanic languages possess a number of defining features compared with other Indo-European languages.

Some of the best-known are the following:

- Thesound changesknown asGrimm's LawandVerner's Law,which shifted the values of all the Indo-European stop consonants (for example, original */tddʰ/became Germanic */θtd/in most cases; comparethreewithLatintres,twowith Latinduo,dowithSanskritdhā-). The recognition of these two sound laws were seminal events in the understanding of the regular nature of linguistic sound change and the development of thecomparative method,which forms the basis of modernhistorical linguistics.

- The development of a strongstresson the first syllable of the word, which triggered significant phonological reduction of all other syllables. This is responsible for the reduction of most of the basic English, Norwegian, Danish and Swedish words into monosyllables, and the common impression of modern English and German as consonant-heavy languages. Examples are Proto-Germanic*strangiþō→strength,*aimaitijō→ant,*haubudą→head,*hauzijaną→hear,*harubistaz→ GermanHerbst"autumn, harvest",*hagatusjō→ GermanHexe"witch, hag".

- A change known asGermanic umlaut,which modified vowel qualities when a high front vocalic segment (/i/,/iː/or/j/) followed in the next syllable. Generally, back vowels were fronted, and front vowels were raised. In many languages, the modified vowels are indicated with aumlautmark (e.g.,ä ö üin German, pronounced/ɛ(ː)œ~øːʏ~yː/,respectively). This change resulted in pervasive alternations in related words — prominent in modern German and present to a lesser extent in modern English (e.g.,mouse/mice,goose/geese,broad/breadth,tell/told,old/elder,foul/filth,gold/gild[42]).

- Large numbers of vowel qualities. English has around 11–12 vowels in most dialects (not counting diphthongs),Standard Swedishhas 17pure vowels (monophthongs),[43]standard German and Dutch 14, andDanishat least 11.[44]The Amstetten dialect ofBavarian Germanhas 13 distinctions among long vowels alone, one of the largest such inventories in the world.[45]

- Verb second(V2) word order, which is uncommon cross-linguistically. Exactly one noun phrase or adverbial element must precede the verb; in particular, if an adverb or prepositional phrase precedes the verb, then the subject must immediately follow the finite verb. In modern English, this survives to a lesser extent, known as "inversion": examples include some constructions withhereorthere(Here comes the sun; there are five continents), verbs of speech after a quote ("Yes", said John), sentences beginning with certain conjunctions (Hardly had he said this when...; Only much later did he realize...) and sentences beginning with certain adverbs of motion to create a sense of drama (Over went the boat; out ran the cat;Pop Goes The Weasel). It is more common in other modern Germanic languages.[example needed]

Other significant characteristics are:

- The reduction of the varioustenseandaspectcombinations of the Indo-European verbal system into only two: thepresent tenseand thepast tense(also called thepreterite).

- The development of a new class ofweak verbsthat use a dentalsuffix(/d/,/t/or/ð/) instead ofvowel alternation(Indo-European ablaut) to indicate past tense. The vast majority of verbs in all Germanic languages are weak; the remaining verbs with vowel ablaut are thestrong verbs.The distinction has been lost in Afrikaans.

- A distinction indefinitenessof anoun phrasethat is marked by different sets of inflectional endings foradjectives,the so-called strong and weak inflections. A similar development happened in theBalto-Slavic languages.This distinction has been lost in modern English but was present inOld Englishand remains in all other Germanic languages to various degrees.

- Some words with etymologies that are difficult to link to other Indo-European families but with variants that appear in almost all Germanic languages. SeeGermanic substrate hypothesis.

- Discourse particles,which are a class of short, unstressed words which speakers use to express their attitude towards the utterance or the hearer. This word category seems to be rare outside of the Germanic languages. An example would be the word 'just', which the speaker can use to express surprise.[46]

Some of the characteristics present in Germanic languages were not present in Proto-Germanic but developed later asareal featuresthat spread from language to language:

- Germanic umlaut only affected theNorthandWest Germanic languages(which represent all modern Germanic languages) but not the now-extinctEast Germanic languages,such asGothic,nor Proto-Germanic, the common ancestor of all Germanic languages.

- The large inventory of vowel qualities is a later development, due to a combination of Germanic umlaut and the tendency in many Germanic languages for pairs of long/short vowels of originally identical quality to develop distinct qualities, with the length distinction sometimes eventually lost. Proto-Germanic had only five distinct vowel qualities, although there were more actual vowel phonemes because length and possibly nasality were phonemic. In modern German, long-short vowel pairs still exist but are also distinct in quality.

- Proto-Germanic probably had a more general S-O-V-I word order. However, the tendency toward V2 order may have already been present in latent form and may be related toWackernagel's Law,an Indo-European law dictating that sentencecliticsmust be placed second.[47]

Roughly speaking, Germanic languages differ in how conservative or how progressive each language is with respect to an overall trend towardanalyticity.Some, such asIcelandicand, to a lesser extent, German, have preserved much of the complexinflectional morphologyinherited from Proto-Germanic (and in turn fromProto-Indo-European). Others, such as English,Swedish,andAfrikaans,have moved toward a largely analytic type.

Linguistic developments

[edit]The subgroupings of the Germanic languages are defined by shared innovations. It is important to distinguish innovations from cases of linguistic conservatism. That is, if two languages in a family share a characteristic that is not observed in a third language, that is evidence of common ancestry of the two languagesonly ifthe characteristic is an innovation compared to the family'sproto-language.

The following innovations are common to theNorthwest Germaniclanguages (all butGothic):

- The lowering of /u/ to /o/ in initial syllables before /a/ in the following syllable:*budą→bode,Icelandicboðs"messages" ( "a-Umlaut", traditionally calledBrechung)

- "Labial umlaut" in unstressed medial syllables (the conversion of /a/ to /u/ and /ō/ to /ū/ before /m/, or /u/ in the following syllable)[48]

- The conversion of /ē1/ into /ā/ (vs. Gothic /ē/) in stressed syllables.[49]In unstressed syllables, West Germanic also has this change, but North Germanic has shortened the vowel to /e/, then raised it to /i/. This suggests it was an areal change.

- The raising of final /ō/ to /u/ (Gothic lowers it to /a/). It is kept distinct from the nasal /ǭ/, which is not raised.

- Themonophthongizationof /ai/ and /au/ to /ē/ and /ō/ in non-initial syllables (however, evidence for the development of /au/ in medial syllables is lacking).

- The development of an intensified demonstrative ending in /s/ (reflected in English "this" compared to "the" )

- Introduction of a distinct ablaut grade in Class VIIstrong verbs,while Gothic usesreduplication(e.g. Gothichaihait;ON, OEhēt,preterite of the Gmc verb*haitan"to be called" )[50]as part of a comprehensive reformation of the Gmc Class VII from a reduplicating to a new ablaut pattern, which presumably started in verbs beginning with vowel or /h/[51](a development which continues the general trend of de-reduplication in Gmc[52]); there are forms (such as OE dial.hehtinstead ofhēt) which retain traces of reduplication even in West and North Germanic

The following innovations are also common to theNorthwest Germaniclanguages but representareal changes:

- Proto-Germanic /z/ > /r/ (e.g. Gothicdius;ONdȳr,OHGtior,OEdēor,"wild animal" ); note that this is not present inProto-Norseand must be ordered afterWest Germanicloss of final /z/

- Germanic umlaut

The following innovations are common to theWest Germanic languages:

- Loss of final /z/. In single-syllable words, Old High German retains it (as /r/), while it disappears in the other West Germanic languages.

- Change of [ð] (fricative allophone of /d/) to stop [d] in all environments.

- Change of /lþ/ to stop /ld/ (except word-finally).[53]

- West Germanic geminationof consonants, exceptr,before /j/. This only occurred in short-stemmed words due toSievers' law.Gemination of /p/, /t/, /k/ and /h/ is also observed before liquids.

- Labiovelar consonants become plain velar when non-initial.

- A particular type ofumlaut/e-u-i/ > /i-u-i/.

- Changes to the 2nd person singular past-tense: Replacement of the past-singular stem vowel with the past-plural stem vowel, and substitution of the ending-twith-ī.

- Short forms (*stān, stēn,*gān, gēn) of the verbs for "stand" and "go"; but note thatCrimean Gothicalso hasgēn.

- The development of agerund.

The following innovations are common to theIngvaeonicsubgroup of theWest Germanic languages,which includes English, Frisian, and in a few cases Dutch and Low German, but not High German:

- The so-calledIngvaeonic nasal spirant law,with loss of /n/ before voiceless fricatives: e.g.*munþ,*gans> Old Englishmūþ, gōs> "mouth, goose", but GermanMund, Gans.

- The loss of the Germanicreflexive pronoun*se-.Dutch has reclaimed the reflexive pronounzichfrom Middle High Germansich.

- The reduction of the three Germanicverbalpluralforms into one form ending in-þ.

- The development of Class III weak verbs into a relic class consisting of four verbs (*sagjan"to say",*hugjan"to think",*habjan"to have",*libjan"to live"; cf. the numerous Old High German verbs in-ēn).

- The split of the Class II weak verb ending*-ō-into*-ō-/-ōja-(cf. Old English-ian<-ōjan,but Old High German-ōn).

- Development of a plural ending*-ōsin a-stem nouns (note, Gothic also has-ōs,but this is an independent development, caused byterminal devoicingof*-ōz;Old Frisianhas-ar,which is thought to be a late borrowing fromDanish). Cf. modern English plural-(e)s,but German plural-e.

- Possibly, themonophthongizationof Germanic*aitoē/ā(this may represent independent changes in Old Saxon andAnglo-Frisian).

The following innovations are common to theAnglo-Frisiansubgroup of theIngvaeonic languages:

- Raising of nasalizeda, āintoo, ō.

- Anglo-Frisian brightening:Fronting of non-nasala, ātoæ,ǣwhen not followed bynorm.

- MetathesisofCrVintoCVr,whereCrepresents any consonant andVany vowel.

- Monophthongizationofaiintoā.

Common linguistic features

[edit]Phonology

[edit]The oldest Germanic languages all share a number of features, which are assumed to be inherited from Proto-Germanic. Phonologically, it includes the important sound changes known asGrimm's LawandVerner's Law,which introduced a large number offricatives;lateProto-Indo-Europeanhad only one, /s/.

The main vowel developments are the merging (in most circumstances) of long and short /a/ and /o/, producing short /a/ and long /ō/. That likewise affected thediphthongs,with PIE /ai/ and /oi/ merging into /ai/ and PIE /au/ and /ou/ merging into /au/. PIE /ei/ developed into long /ī/. PIE long /ē/ developed into a vowel denoted as /ē1/ (often assumed to be phonetically[æː]), while a new, fairly uncommon long vowel /ē2/ developed in varied and not completely understood circumstances. Proto-Germanic had nofront rounded vowels,but all Germanic languages except forGothicsubsequently developed them through the process ofi-umlaut.

Proto-Germanic developed a strong stress accent on the first syllable of the root, but remnants of the original free PIE accent are visible due to Verner's Law, which was sensitive to this accent. That caused a steady erosion of vowels in unstressed syllables. In Proto-Germanic, that had progressed only to the point that absolutely-final short vowels (other than /i/ and /u/) were lost and absolutely-final long vowels were shortened, but all of the early literary languages show a more advanced state of vowel loss. This ultimately resulted in some languages (like Modern English) losing practically all vowels following the main stress and the consequent rise of a very large number of monosyllabic words.

Table of outcomes

[edit]The following table shows the main outcomes of Proto-Germanic vowels and consonants in the various older languages. For vowels, only the outcomes in stressed syllables are shown. Outcomes in unstressed syllables are quite different, vary from language to language and depend on a number of other factors (such as whether the syllable was medial or final, whether the syllable wasopenorclosedand (in some cases) whether the preceding syllable waslightorheavy).

Notes:

- C-means before a vowel (word-initially, or sometimes after a consonant).

- -C-means between vowels.

- -Cmeans after a vowel (word-finally or before a consonant). Word-final outcomes generally occurredafterdeletion of final short vowels, which occurred shortly after Proto-Germanic and is reflected in the history of all written languages except forProto-Norse.

- The above three are given in the orderC-,-C-,-C.If one is omitted, the previous one applies. For example,f, -[v]-means that[v]occurs after a vowel regardless of what follows.

- Something likea(…u)means "aif /u/ occurs in the next syllable ".

- Something likea(n)means "aif /n/ immediately follows ".

- Something like(n)ameans "aif /n/ immediately precedes ".

| Proto-Germanic[54][1] | (Pre-)Gothic[a][55][56] | Old Norse[57] | Old English[58][59][60][61][62][63][64] | Old High German[65][66] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | a | a, ɔ(...u)[b] | æ, a(...a),[c]a/o(n), æ̆ă(h,rC,lC)[d] | a |

| a(...i)[e] | e, ø(...u)[b] | e, æ, ĭy̆(h,rC,lC)[d] | e, a(hs,ht,Cw) | |

| ãː | aː | aː | oː | aː |

| ãː(...i)[e] | æː | eː | äː | |

| æː | eː, ɛː(V) | aː | æː, æa(h)[d] | aː |

| æː(...i)[e] | æː | æː | äː | |

| e | i, ɛ(h,hʷ,r) | ja,[f]jø(...u),[b](w,r,l)e, (w,r,l)ø(...u)[b] | e, ĕŏ(h,w,rC)[d] | e, i(...u) |

| e(...i)[e] | i, y(...w)[b] | i | i | |

| eː | eː, ɛː(V) | eː | eː | ie |

| i | i, ɛ(h,hʷ,r) | i, y(...w)[b] | i, ĭŭ(h,w,rC)[d] | i |

| iː | iː | iː | iː, iu(h) | iː |

| oː | oː, ɔː(V) | oː | oː | uo |

| oː(...i)[e] | øː | eː | üö | |

| u | u, ɔ(h,hʷ,r) | u, o(...a)[c] | u, o(...a)[c] | u, o(...a)[c] |

| u(...i)[e] | y | y | ü | |

| uː | uː, ɔː(V) | uː | uː | uː |

| uː(...i)[e] | yː | yː | üː | |

| ai | ai[a] | ei, ey(...w),[b]aː(h,r)[g] | aː | ei, eː(r,h,w,#)[h] |

| ai(...i)[e] | ei, æː(h,r) | æː | ||

| au | au[a] | au, oː(h) | æa | ou, oː(h,T)[i] |

| au(...i)[e] | ey, øː(h) | iy | öü, öː(h,T)[i] | |

| eu | iu | juː, joː(T)[j] | eo | io, iu(...i/u)[c] |

| eu(...i)[e] | yː | iy | ||

| p | p | p | p | pf-, -ff-, -f |

| t | t | t | t | ts-, -ss-, -s[k] |

| k | k | k | k, tʃ(i,e,æ)-, -k-, -(i)tʃ-, -tʃ(i)-[l] | k-, -xx-, -x |

| kʷ | kʷ | kv, -k | kw-, -k-, -(i)tʃ-, -tʃ(i)-[l] | kw-, -xx-, -x |

| b-, -[β]-[m] | b-, -[β]-, -f | b-, -[v]- | b-, -[v]-, -f | b |

| d-, -[ð]-[m] | d-, -[ð]-, -þ | d-, -[ð]- | d | t |

| [ɣ]-, -[ɣ]-[m] | g-, -[ɣ]-, -[x] | g-, -[ɣ]- | g-, j(æ,e,i)-, -[ɣ]-, -j(æ,e,i)-, -(æ,e,i)j-[l] | g |

| f | f | f, -[v]- | f, -[v]-, -f | f, p |

| þ | þ | þ, -[ð]- | þ, -[ð]-, -þ | d |

| x | h | h, -∅- | h, -∅-, -h | h |

| xʷ | hʷ | xv, -∅- | hw, -∅-, -h | hw, -h- |

| s | s | s-, -[z]- | s-, -[z]-, -s | ṣ-, -[ẓ]-, -ṣ[k] |

| z | -z-, -s | r | -r-, -∅ | -r-, -∅ |

| r[n] | r | r | r | r |

| l | l | l | l | l |

| n | n | n-, -∅(s,p,t,k),[o]-∅[p] | n, -∅(f,s,þ)[o] | n |

| m | m | m | m | m |

| j[q] | j | ∅-, -j-, -∅ | j | j |

| w[q] | w | ∅-, v-(a,e,i), -v-, -∅ | w | w |

- ^abcTheGothic writing systemuses the spelling⟨ai⟩to represent vowels that derive primarily from four different sources:

- Proto-Germanic /ai/

- Proto-Germanic/eː/and/æː/before vowels

- Proto-Germanic /e/ and /i/ before /h/, /hʷ/ and /r/

- Greek/ɛ/.

- Proto-Germanic /au/

- Proto-Germanic/oː/and/uː/before vowels

- Proto-Germanic /u/ before /h/, /hʷ/ and /r/

- Greek/ɔ/.

- ^abcdefgIn Old Norse, non-rounded vowels become rounded when a /u/ or /w/ follows in the next syllable, in a process known asu-umlaut.Some vowels were affected similarly, but only by a following /w/; this process is sometimes termedw-umlaut.These processes operated afteri-umlaut.U-umlaut(by a following /u/ or /w/) caused /a/, /ja/ (broken /e/), /aː/, and /e/ to round to /ɔ/ (writtenǫ), /jɔ/ (writtenjǫ), /ɔː/ (writtenǫ́and later unrounded again to /aː/), and /ø/, respectively. The vowels /i/ and /ai/ rounded to /y/ and /ey/, respectively, only before /w/. Short /a/ become /ø/ by a combination of i-umlaut and w-umlaut.

- ^abcdeA process known asa-mutationora-umlautcaused short /u/ to lower to /o/ before a non-high vowel (usually /a/) in the following syllable. All languages except Gothic were affected, although there are various exceptions in all the languages. Two similar process later operated:

- In Old High German, /iu/ (from Proto-Germanic /eu/,/iu/) became /io/ before a non-high vowel in the next syllable.

- In Old English, /æ/ (from Proto-Germanic /a/) became /a/ before /a/ in the next syllable.

- ^abcdeThe diphthongal results are due toOld English breaking.In general, front vowels break into diphthongs before some subset ofh,w,rC,andlC,whereCis a consonant. The diphthong /æa/ is writtenea;/eo/ is writteneo;/iu/ is writtenio;and /iy/ is writtenie.All diphthongs umlaut to /iy/ie.All diphthongs occur both long and short. Note that there is significant dispute about the actual pronunciation ofioand (especially)ie.Their interpretation as /iu/ and /iy/, respectively, follows Lass (1994),Old English: A historical linguistic companion.

- ^abcdefghijAll languages except Gothic were affected byi-umlaut.This was the most significant of the variousumlautprocesses operating in the Germanic languages, and caused back vowels to become fronted, and front vowels to be raised, when /i/, /iː/ or /j/ followed in the next syllable. The termi-umlautactually refers to two separate processes that both were triggered in the same environment. The earlier process raised /e/ and /eu/ to /i/ and /iu/, respectively, and may have operated still in Proto-Germanic (with its effects in Gothic obscured due to later changes). The later process affected all back vowels and some front vowels; it operated independently in the various languages, occurring at differing times with differing results. Old English was the earliest and most-affected language, with nearly all vowels affected. Old High German was the last language to be affected; the only written evidence of the process is with short /a/, which is umlauted to /e/. However, later evidence suggests that other back vowels were also affected, perhaps still sub-phonemically in Old High German times. These are indicated with adiaeresisor "umlaut" symbol (two dots) placed over the affected vowels.

- ^Proto-Germanic /e/ usually became Old Norse /ja/ by a process known asvowel breaking.

- ^Before Proto-Germanic /x/, /xʷ/ or /r/, but not before Proto-Germanic /z/ (which only merged with /r/ much later in North Germanic). Cf. Old Norseárr(masc.) "messenger" < PG *airuz,ár(fem.) "oar" < PG *airō, vs.eir(fem.) "honor" < PG *aizō,eir(neut.) "bronze" < PG *aizan. (All four becomeārin Old English; in Gothic, they become, respectively,airus,(unattested),*aiza,*aiz.) Cf.Köbler, Gerhard."Altenglisches Wörterbuch"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 18 April 2003.

- ^Before /r/, /h/ (including when derived from Proto-Germanic /xʷ/) or /w/, or word-finally.

- ^abBefore /h/ (including when derived from Proto-Germanic /xʷ/) or before anydental consonant,i.e. /s/,/z/,/þ/,/t/,/d/,/r/,/l/,/n/.

- ^Before anydental consonant,i.e. /s/,/z/,/þ/,/t/,/d/,/r/,/l/,/n/.

- ^abThe result of theHigh German consonant shiftproduced a different sort ofsthan the original Proto-Germanics.The former was written⟨z⟩and the latter⟨s⟩.It is thought that the former was adental/s/, somewhat like in English, while the latter was an "apicoalveolar"sound as in modern European Spanish, sounding somewhere between English /s/ and /ʃ/.Joos (1952)) Modern standard German has /ʃ/ for this sound in some contexts, e.g. initially before a consonant (schlimmcf. Englishslim;Stand/ʃtant/, cf. Englishstand), and after /r/ (Arsch,cf. Englisharseorass). A number of modern southern German dialects have /ʃ/ for this sound before all consonants, whether or not word-initially.

- ^abcOld Englishpalatalizes/k,g,ɣ/ to /tʃ,dʒ,j/ near a front vowel. The sounds /k/ and /ɣ/ palatalized initially before any front vowel. Elsewhere /ɣ/ palatalized before /j/ orbefore or afterany front vowel, where /k/ and /g/ (which occurred only in the combinations /gg/, /ng/) palatalized before /j/, or either before or after /i,iː/.

- ^abcVoiced fricatives were originally allophones of voiced stops, when occurring after a vowel or after certain consonants (and for /g/, also initially — hard [g] occurred only in the combinations /gg/, /ng/). In Old Norse and Old English, voiceless fricatives became voiced between vowels (and finally after a vowel in Old Norse); as a result, voiced fricatives were reanalyzed as allophones of voiceless fricatives. In Old High German, all voiced fricatives hardened into stops.

- ^In the early periods of the various languages, the sound written /r/ may have been stronglyvelarized,as in modernAmerican English(Lass 1994); this is one possible explanation for the various processes were triggered byh(probably[x]) andr.

- ^abOld English and Old Norse lose /n/ before certain consonants, with the previous vowel lengthened (in Old Norse, the following consonant is also lengthened).

- ^/n/ lost finally and before /s,p,t,k/, but not before other consonants.

- ^abProto-Germanic /j/ and /w/ were often lost between vowels in all languages, often with /j/ or /w/ later reappearing to break the hiatus, and not always corresponding to the sound previously present. After a consonant, Gothic consistently preserved /j/ and /w/, but most languages deleted /j/ (after triggeringi-umlaut), and /w/ sometimes disappeared. The loss of /j/ after a consonant occurred in the various languages at different times and to differing degrees. For example, /j/ was still present in most circumstances in written Old Saxon, and was still present in Old Norse when a short vowel preceded and a back vowel followed; but in Old English and Old High German, /j/ only remained after an /r/ preceded by a short vowel.

Morphology

[edit]The oldest Germanic languages have the typical complex inflected morphology of oldIndo-European languages,with four or five noun cases; verbs marked for person, number, tense and mood; multiple noun and verb classes; few or no articles; and rather free word order. The old Germanic languages are famous for having only two tenses (present and past), with three PIE past-tense aspects (imperfect, aorist, and perfect/stative) merged into one and no new tenses (future, pluperfect, etc.) developing. There were three moods: indicative, subjunctive (developed from the PIEoptative mood) and imperative. Gothic verbs had a number of archaic features inherited from PIE that were lost in the other Germanic languages with few traces, including dual endings, an inflected passive voice (derived from the PIEmediopassive voice), and a class of verbs with reduplication in the past tense (derived from the PIE perfect). The complex tense system of modern English (e.g.In three months, the house will still be being builtorIf you had not acted so stupidly, we would never have been caught) is almost entirely due to subsequent developments (although paralleled in many of the other Germanic languages).

Among the primary innovations in Proto-Germanic are thepreterite present verbs,a special set of verbs whose present tense looks like the past tense of other verbs and which is the origin of mostmodal verbsin English; a past-tense ending; (in the so-called "weak verbs", marked with-edin English) that appears variously as /d/ or /t/, often assumed to be derived from the verb "to do"; and two separate sets of adjective endings, originally corresponding to a distinction between indefinite semantics ( "a man", with a combination of PIE adjective and pronoun endings) and definite semantics ( "the man", with endings derived from PIEn-stem nouns).

Note that most modern Germanic languages have lost most of the inherited inflectional morphology as a result of the steady attrition of unstressed endings triggered by the strong initial stress. (Contrast, for example, theBalto-Slavic languages,which have largely kept the Indo-Europeanpitch accentand consequently preserved much of the inherited morphology.)Icelandicand to a lesser extent modern German best preserve the Proto–Germanic inflectional system, with four noun cases, three genders, and well-marked verbs. English and Afrikaans are at the other extreme, with almost no remaining inflectional morphology.

The following shows a typical masculinea-stem noun, Proto-Germanic*fiskaz( "fish" ), and its development in the various old literary languages:

| Proto-Germanic | Gothic | Old Norse | Old High German | Middle High German | Modern German | Old English | Old Saxon | Old Frisian | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Nominative | *fisk-az | fisk-s | fisk-r | visk | visch | Fisch | fisc | fisc | fisk |

| Vocative | *fisk | fisk | ||||||||

| Accusative | *fisk-ą | fisk | fisk | |||||||

| Genitive | *fisk-as, -is | fisk-is | fisk-s | visk-es | visch-es | Fisch-es[68] | fisc-es < fisc-æs | fisc-as, -es | fisk-is, -es | |

| Dative | *fisk-ai | fisk-a | fisk-i | visk-a | visch-e | Fisch-(e)[69] | fisc-e < fisc-æ | fisc-a, -e | fisk-a, -i, -e | |

| Instrumental | *fisk-ō | fisk-a | — | visk-u | — | — | fisc-e < fisc-i[70] | fisc-u | — | |

| Plural | Nominative, Vocative | *fisk-ôs, -ôz | fisk-ōs | fisk-ar | visk-a | visch-e | Fisch-e | fisc-as | fisc-ōs, -ās | fisk-ar, -a |

| Accusative | *fisk-anz | fisk-ans | fisk-a | visk-ā | ||||||

| Genitive | *fisk-ǫ̂ | fisk-ē | fisk-a | visk-ō | fisc-a | fisc-ō, -ā | fisk-a | |||

| Dative | *fisk-amaz | fisk-am | fisk-um, -om | visk-um | visch-en | Fisch-en | fisc-um | fisc-un, -on | fisk-um, -on, -em | |

| Instrumental | *fisk-amiz | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

Strong vs. weak nouns and adjectives

[edit]Originally, adjectives in Proto-Indo-European followed the same declensional classes as nouns. The most common class (theo/āclass) used a combination ofo-stem endings for masculine and neuter genders andā-stems ending for feminine genders, but other common classes (e.g. theiclass anduclass) used endings from a single vowel-stem declension for all genders, and various other classes existed that were based on other declensions. A quite different set of "pronominal" endings was used for pronouns,determiners,and words with related semantics (e.g., "all", "only" ).

An important innovation in Proto-Germanic was the development of two separate sets of adjective endings, originally corresponding to a distinction between indefinite semantics ( "a man" ) and definite semantics ( "the man" ). The endings of indefinite adjectives were derived from a combination of pronominal endings with one of the common vowel-stem adjective declensions – usually theo/āclass (often termed thea/ōclass in the specific context of the Germanic languages) but sometimes theioruclasses. Definite adjectives, however, had endings based onn-stem nouns. Originally both types of adjectives could be used by themselves, but already by Proto-Germanic times a pattern evolved whereby definite adjectives had to be accompanied by adeterminerwith definite semantics (e.g., adefinite article,demonstrative pronoun,possessive pronoun,or the like), while indefinite adjectives were used in other circumstances (either accompanied by a word with indefinite semantics such as "a", "one", or "some" or unaccompanied).

In the 19th century, the two types of adjectives – indefinite and definite – were respectively termed "strong" and "weak", names which are still commonly used. These names were based on the appearance of the two sets of endings in modern German. In German, the distinctive case endings formerly present on nouns have largely disappeared, with the result that the load of distinguishing one case from another is almost entirely carried by determiners and adjectives. Furthermore, due to regular sound change, the various definite (n-stem) adjective endings coalesced to the point where only two endings (-eand-en) remain in modern German to express the sixteen possible inflectional categories of the language (masculine/feminine/neuter/plural crossed with nominative/accusative/dative/genitive – modern German merges all genders in the plural). The indefinite (a/ō-stem) adjective endings were less affected by sound change, with six endings remaining (-, -e, -es, -er, -em, -en), cleverly distributed in a way that is capable of expressing the various inflectional categories without too much ambiguity. As a result, the definite endings were thought of as too "weak" to carry inflectional meaning and in need of "strengthening" by the presence of an accompanying determiner, while the indefinite endings were viewed as "strong" enough to indicate the inflectional categories even when standing alone. (This view is enhanced by the fact that modern German largely uses weak-ending adjectives when accompanying an indefinite article, and hence the indefinite/definite distinction no longer clearly applies.) By analogy, the terms "strong" and "weak" were extended to the corresponding noun classes, witha-stem andō-stem nouns termed "strong" andn-stem nouns termed "weak".

However, in Proto-Germanic – and still inGothic,the most conservative Germanic language – the terms "strong" and "weak" are not clearly appropriate. For one thing, there were a large number of noun declensions. Thea-stem,ō-stem, andn-stem declensions were the most common and represented targets into which the other declensions were eventually absorbed, but this process occurred only gradually. Originally then-stem declension was not a single declension but a set of separate declensions (e.g.,-an,-ōn,-īn) with related endings, and these endings were in no way any "weaker" than the endings of any other declensions. (For example, among the eight possible inflectional categories of a noun — singular/plural crossed with nominative/accusative/dative/genitive — masculinean-stem nouns in Gothic include seven endings, and feminineōn-stem nouns include six endings, meaning there is very little ambiguity of "weakness" in these endings and in fact much less than in the German "strong" endings.) Although it is possible to group the various noun declensions into three basic categories — vowel-stem,n-stem, and other-consonant-stem (a.k.a. "minor declensions" ) — the vowel-stem nouns do not display any sort of unity in their endings that supports grouping them together with each other but separate from then-stem endings.

It is only in later languages that the binary distinction between "strong" and "weak" nouns become more relevant. InOld English,then-stem nouns form a single, clear class, but the masculinea-stem and feminineō-stem nouns have little in common with each other, and neither has much similarity to the small class ofu-stem nouns. Similarly, in Old Norse, the masculinea-stem and feminineō-stem nouns have little in common with each other, and the continuations of the masculinean-stem and feminineōn/īn-stem nouns are also quite distinct. It is only inMiddle Dutchand modern German that the various vowel-stem nouns have merged to the point that a binary strong/weak distinction clearly applies.

As a result, newer grammatical descriptions of the Germanic languages often avoid the terms "strong" and "weak" except in conjunction with German itself, preferring instead to use the terms "indefinite" and "definite" for adjectives and to distinguish nouns by their actual stem class.

In English, both sets of adjective endings were lost entirely in the lateMiddle Englishperiod.

Classification

[edit]Note that divisions between and among subfamilies of Germanic are rarely precisely defined; most form continuous clines, with adjacentvarietiesbeing mutually intelligible and more separated ones not. Within the Germanic language family areEast Germanic,West Germanic,andNorth Germanic.However, East Germanic languages became extinct several centuries ago.[when?]

All living Germanic languages belong either to theWest Germanicor to theNorth Germanicbranch. The West Germanic group is the larger by far, further subdivided intoAnglo-Frisianon one hand andContinental West Germanicon the other. Anglo-Frisian notably includes English and all itsvariants,while Continental West Germanic includes German (standard registeranddialects), as well as Dutch (standard registeranddialects). East Germanic includes most notably the extinct Gothic and Crimean Gothic languages.

Modern classification looks like this. For a full classification, seeList of Germanic languages.

- Germanic

- West Germanic

- High German languages(includesStandard Germanandits dialects)

- Upper German

- Yiddish

- High Franconian(a transitional dialect between Upper and Central German)

- Central German

- Low German

- West Low German

- East Low German

- Plautdietsch(Mennonite Low German)

- Low Franconian

- Dutchandits dialects

- Afrikaans(a separatestandard language)

- Limburgish(anofficial minority *language)

- Anglo-Frisian

- Anglic(or English)

- Englishandits dialects

- Scotsin Scotland andUlster

- Frisian

- West Frisian

- East Frisian

- Saterland Frisian(last remaining dialect of East Frisian)

- North Frisian

- Anglic(or English)

- High German languages(includesStandard Germanandits dialects)

- North Germanic

- East Germanic

- West Germanic

Writing

[edit]

• Early Middle Ages

• Early Twentieth Century

The earliest evidence of Germanic languages comes from names recorded in the 1st century byTacitus(especially from his workGermania), but the earliest Germanic writing occurs in a single instance in the 2nd century BC on theNegau helmet.[72]

From roughly the 2nd century AD, certain speakers of early Germanic varieties developed theElder Futhark,an early form of therunic Alpha bet.Early runic inscriptions also are largely limited to personal names and difficult to interpret. TheGothic languagewas written in theGothic Alpha betdeveloped by BishopUlfilasfor his translation of theBiblein the 4th century.[73]Later, Christian priests and monks who spoke and readLatinin addition to their native Germanic varieties began writing the Germanic languages with slightly modified Latin letters. However, throughout theViking Age,runic Alpha bets remained in common use in Scandinavia.

Modern Germanic languages mostly use an Alpha bet derived from theLatin Alphabet.In print, German used to be predominately set inblacklettertypefaces(e.g.,frakturorschwabacher)untilthe 1940s, whileKurrentand, since the early 20th century,Sütterlinwere formerly used for German handwriting. Yiddish is written using an adaptedHebrew Alpha bet.

Vocabulary comparison

[edit]The table compares cognates in several different Germanic languages. In some cases, the meanings may not be identical in each language.

| West Germanic | North Germanic | East Germanic |

Reconstructed Proto-Germanic[74] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglo-Frisian | Continental | West | East | |||||||

| English | West Frisian | Dutch | Low German[75] | German | Icelandic | Norwegian (Nynorsk) |

Swedish | Danish | Gothic † | |

| apple | apel | appel | Appel | Apfel | epli | eple | äpple | æble | apel[76] | *ap(u)laz |

| can | kinne | kunnen | känen | können | kunna | kunne, kunna | kunna | kunne | kunnan | *kanna |

| daughter | dochter | dochter | Dochter | Tochter | dóttir | dotter | dotter | datter | dauhtar | *đuχtēr |

| dead | dea | dood | dod | tot | dauður | daud | död | død | dauþs | *đauđaz |

| deep | djip | diep | deip | tief | djúpur | djup | djup | dyb | diups | *đeupaz |

| earth | ierde | aarde | Ir(d) | Erde | jörð | jord | jord | jord | airþa | *erþō |

| egg[77] | aei, aai | ei | Ei | Ei | egg | egg | ägg | æg | *addi[78] | *ajjaz |

| fish | fisk | vis | Fisch | Fisch | fiskur | fisk | fisk | fisk | fisks | *fiskaz |

| go | gean | gaan | gahn | gehen | ganga | gå | gå(nga) | gå (gange) | gaggan | *ȝanȝanan |

| good | goed | goed | gaud | gut | góð(ur) | god | god | god | gōþ(is) | *ȝōđaz |

| hear | hearre | horen | hüren | hören | heyra | høyra, høyre | höra | høre | hausjan | *χauzjanan, *χausjanan |

| I | ik | ik | ick | ich | ég | eg | jag | jeg | ik | *eka |

| live | libje | leven | lewen | leben | lifa | leva | leva | leve | liban | *liƀēnan |

| night | nacht | nacht | Nacht | Nacht | nótt | natt | natt | nat | nahts | *naχtz |

| one | ien | één | ein, en | eins | einn | ein | en | en | áins | *ainaz |

| ridge | rêch | rug | Rügg(en) | Rücken | hryggur | rygg | rygg | ryg | – | *χruȝjaz |

| sit | sitte | zitten | sitten | sitzen | sitja | sitja, sitta | sitta | sidde | sitan | *setjanan |

| seek | sykje | zoeken | säuken | suchen | sækja | søkja | söka | søge | sōkjan | *sōkjanan |

| that | dat | dat | dat | das | það | det | det | det | þata | *þat |

| thank (noun) | tank | dank | Dank | Dank | þökk | takk | tack | tak | þagks | *þankaz |

| true | trou | trouw | tru | treu | tryggur | trygg | trygg | tryg | triggws | *trewwaz |

| two | twa | twee | twei | zwei, zwo | tveir, tvær, tvö | to[79] | två, tu | to | twái, twós, twa | *twō(u) |

| us | ús | ons | uns | uns | oss | oss | oss | os | uns | *uns- |

| way | wei | weg | Weg | Weg | vegur | veg | väg | vej | wigs | weȝaz |

| white | wyt | wit | witt | weiß | hvítur | kvit | vit | hvid | ƕeits | *χwītaz |

| word | wurd | woord | Wurd | Wort | orð | ord | ord | ord | waurd | *wurđan |

| year | jier | jaar | Johr | Jahr | ár | år | år | år | jēr | *jēran |

See also

[edit]- List of Germanic languages

- Language families and languages

- List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents

- Germanization

- Anglicization

- Germanic name

- Germanic verband its various subordinated articles

- Germanic placename etymology

- German name

- Isogloss

- South Germanic languages

Footnotes

[edit]- ^Estimates of native speakers of the Germanic languages vary from 450 million[1]through 500 million and up to more than 520 million. Much of the uncertainty is caused by the rapid spread of theEnglish languageand conflicting estimates of its native speakers. Here used is the most probable estimate (currently 515 million) as determined byStatisticssection below.

- ^There are various conflicting estimates of L1/native users of English, from 360 million up to 430 million and more. English is a currentlingua franca,which is spreading rapidly, often replacing other languages throughout the world, thus making it difficult to provide one definitive number. It is a rare case of a language with many more secondary speakers than natives.

- ^This phenomenon is not restricted to German but constitutesa common linguistic developmentaffecting all modern-day living major languages with a complex set of dialects. As local dialects increasingly cease to be used, they are usually replaced by a standardized version of the language.

- ^It uses the lowest estimate for English (360 million).

- ^Estimates for English, German and Dutch are less precise than these for the rest of the Germanic languages. These three languages are the most widely spoken ones; the rest are largely concentrated in specific places (excluding Yiddish and Afrikaans), so precise estimates are easier to get.

- ^Estimate includes mostHigh Germandialects classified into the German language spectrum, while leaves some out like theYiddish language.Low Germanis regarded separately.

- ^All other Germanic languages, includingGutnish,Dalecarlian dialects(among themElfdalian) and any other minor languages.

- ^Estimates of native speakers of the Germanic languages vary from 450 million[1]through 500 million and up to more than 520 million. Much of the uncertainty is caused by the rapid spread of theEnglish languageand conflicting estimates of its native speakers. Here used is the most probable estimate as determined byStatisticssection.

Notes

[edit]- ^abcKönig & van der Auwera (1994).

- ^Bell-Fialkoll, Andrew, ed. (2000).The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe: Sedentary Civilization v. "Barbarian" and Nomad.Palgrave Macmillan. p. 117.ISBN0-312-21207-0.

- ^"Germanic languages - Proto-Germanic, Indo-European, Germanic Dialects | Britannica".Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2023.Retrieved29 December2023.

- ^ab"Världens 100 största språk 2010"[The world's 100 largest languages in 2010].Nationalencyklopedin(in Swedish). 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2014.Retrieved12 February2014.

- ^SIL Ethnologue (2006). 95 million speakers ofStandard German;105 million including Middle and UpperGerman dialects;120 million includingLow GermanandYiddish.

- ^"Afrikaans".Archivedfrom the original on 3 December 2013.Retrieved3 August2016.

- ^abTaaltelling NedersaksischArchived5 October 2021 at theWayback Machine,H. Bloemhoff. (2005). p88.

- ^abStatus und Gebrauch des Niederdeutschen 2016Archived16 January 2021 at theWayback Machine,A. Adler, C. Ehlers, R. Goltz, A. Kleene, A. Plewnia (2016)

- ^Saxon, LowArchived2 January 2018 at theWayback MachineEthnologue.

- ^The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic, and Educational Perspectives by Guus Extra, Durk Gorter; Multilingual Matters, 2001 – 454; page 10.

- ^abDovid Katz."YIDDISH"(PDF).YIVO.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 22 March 2012.Retrieved20 December2015.

- ^Holmberg, Anders and Christer Platzack (2005). "The Scandinavian languages". InThe Comparative Syntax Handbook,edsGuglielmo Cinqueand Richard S. Kayne. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.Excerpt at Durham UniversityArchived3 December 2007 at theWayback Machine.

- ^"1 Cor. 13:1–12".lrc.la.utexas.edu.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2021.Retrieved3 August2016.

- ^"Germanic".Archivedfrom the original on 18 July 2013.Retrieved3 August2016.

- ^Heine, Matthias (16 November 2017)."Sprache und Mundart: Das Aussterben der deutschen Dialekte".Die Welt.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2021.Retrieved4 October2018.

- ^TheMiskito Coastused to be a part ofBritish Empire

- ^"Office pour la langue et les cultures d'Alsace et de Moselle".olcalsace.org.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2023.Retrieved19 January2023.

- ^Pierre Vogler."Le dialecte alsacien: vers l'oubli".hal.science.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2023.Retrieved14 July2021.

- ^"Feiten en cijfers – Taalunieversum".taalunieversum.org.Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2022.Retrieved11 April2015.

- ^Dutch-speakers can understand Afrikaans with some difficulty, but Afrikaans-speakers have a harder time understanding Dutch because of the simplified grammar of Afrikaans, compared to that of Dutch,http:// let.rug.nl/~gooskens/pdf/publ_litlingcomp_2006b.pdfArchived4 March 2016 at theWayback Machine

- ^"A co-oficialização da língua pomerana"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 December 2012.Retrieved11 October2012.

- ^"List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148".Conventions.coe.int.Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2011.Retrieved9 September2012.

- ^"An intro to 'Lëtzebuergesch'".Archivedfrom the original on 12 April 2023.Retrieved18 April2023.

- ^Koyfman, Steph (29 April 2018)."How Many People Speak Swedish, And Where Is It Spoken?".Babbel Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2024.Retrieved11 June2024.

- ^Vasagar, Jeevan (18 June 2013)."German 'should be a working language of EU', says Merkel's party".Archivedfrom the original on 11 January 2022 – via The Telegraph.

- ^"Nederlands, wereldtaal".Nederlandse Taalunie. 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2012.Retrieved7 April2011.

- ^Nationalencyklopedin"Världens 100 största språk 2007" The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007

- ^"Afrikaans - Worldwide distribution".Worlddata.info.October 2023 [April 2015].Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2024.Retrieved3 April2024.

- ^"Danish".ethnologue.Archivedfrom the original on 8 February 2021.Retrieved18 June2014.

- ^"Befolkningen".ssb.no(in Norwegian).Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2021.Retrieved29 November2018.

- ^"Status und Gebrauch des Niederdeutschen 2016"(PDF).ins-bremen.de.p. 40. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 January 2021.Retrieved13 March2021."Taaltelling Nedersaksisch"(PDF).stellingia.nl.p. 78.Archived(PDF)from the original on 5 October 2021.Retrieved13 March2021.

- ^Jacobs (2005).

- ^"Scots".Ethnologue.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2021.Retrieved12 March2015.

- ^"Frisian".Ethnologue.Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2021.Retrieved18 June2014.

- ^SeeLuxembourgish language.

- ^"Statistics Iceland".Statistics Iceland.Archivedfrom the original on 26 May 2020.Retrieved18 June2014.

- ^"Faroese".ethnologue.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2021.Retrieved18 June2014.

- ^Kinder, Hermann (1988),Penguin Atlas of World History,vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108,ISBN0-14-051054-0.

- ^"Languages of the World: Germanic languages".The New Encyclopædia Britannica.Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993.ISBN0-85229-571-5.

- ^"Germanic languages | Definition, Language Tree, & List | Britannica".britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2023.Retrieved11 June2024.

- ^Ringe (2006),p. 67.

- ^These alternations are no longer easily distinguishable from vowel alternations due to earlier changes (e.g.Indo-European ablaut,as inwrite/wrote/written,sing/sang/sung,hold/held) or later changes (e.g. vowel shortening inMiddle English,as inwide/width,lead/led).

- ^Wang et al. (2012),p. 657.

- ^Basbøll & Jacobsen (2003).

- ^Ladefoged, Peter;Maddieson, Ian(1996).The Sounds of the World's Languages.Oxford: Blackwell. p. 290.ISBN0-631-19815-6.

- ^Harbert, Wayne. (2007).The Germanic languages.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–35.ISBN978-0-511-26991-2.OCLC252534420.

- ^According toDonald Ringe,cf.Ringe (2006:295)

- ^Campbell (1983),p. 139.

- ^But seeCercignani (1972)

- ^See alsoCercignani (1979)

- ^Bethge (1900),p. 361.

- ^Schumacher (2005),p. 603f.

- ^Campbell (1983),p. 169.

- ^abRinge (2006).

- ^Bennett (1980).

- ^Wright (1919).

- ^Gordon (1927).

- ^Campbell (1959).

- ^Diamond (1970).

- ^Lass & Anderson (1975).

- ^abLass (1994).

- ^Mitchell & Robinson (1992).

- ^Robinson (1992).

- ^Wright & Wright (1925).

- ^Wright (1906).

- ^Waterman (1976).

- ^Helfenstein (1870).

- ^In speech, the genitive is usually replaced withvom+ dative, or with the dative alone after prepositions.

- ^The use of-ein the dative has become increasingly uncommon, and is found only in a few fixed phrases (e.g.zu Hause"at home" ) and in certain archaizing literary styles.

- ^Of questionable etymology. Possibly an old locative.

- ^van Durme, Luc (2002). "Genesis and Evolution of the Romance-Germanic Language Border in Europe". In Treffers-Daller, Jeanine; Willemyns, Roland (eds.).Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border(PDF).Multilingual Matters. p. 13.ISBN9781853596278.Archived(PDF)from the original on 16 September 2020.

- ^Todd (1992).

- ^Cercignani, Fausto,The Elaboration of the Gothic Alphabet and Orthography,in "Indogermanische Forschungen", 93, 1988, pp. 168–185.

- ^Forms follow Orel 2003. þ represents IPA [θ], χ IPA [x], ȝ IPA [γ], đ IPA [ð], and ƀ IPA [β].

- ^Low German forms follow the dictionary ofReuter, Fritz (1905).Das Fritz-Reuter-Wörterbuch.Digitales Wörterbuch Niederdeutsch (dwn).Archivedfrom the original on 22 October 2021.Retrieved22 October2021.

- ^Attested in this form in Crimean Gothic. See Winfred Lehmann,A Gothic Etymological Dictionary(Brill: Leiden, 1986), p. 40.

- ^The English word is a loan from Old Norse.

- ^Attested in Crimean Gothic in the nominative plural asada.See Winfred Lehmann,A Gothic Etymological Dictionary(Brill: Leiden, 1986), p. 2.

- ^Dialectally tvo, två, tvei (m), tvæ (f), tvau (n).

Sources

[edit]- Basbøll, Hans; Jacobsen, Henrik Galberg (2003).Take Danish, for Instance: Linguistic Studies in Honour of Hans Basbøll Presented on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday, 12 July 2003.University Press of Southern Denmark. pp. 41–57.ISBN9788778388261.

- Bethge, Richard (1900). "Konjugation des Urgermanischen". In Ferdinand Dieter (ed.).Laut- und Formenlehre der altgermanischen Dialekte (2. Halbband: Formenlehre).Leipzig: Reisland.

- Cercignani, Fausto(1972), "Indo-European ē in Germanic",Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Sprachforschung,86(1): 104–110

- Cercignani, Fausto(1979), "The Reduplicating Syllable and Internal Open Juncture in Gothic",Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Sprachforschung,93(11): 126–132

- Jacobs, Neil G. (2005).Yiddish: A Linguistic Introduction.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521772150– via Google Books.

- Joos, Martin (1952). "The Medieval Sibilants".Language.28(2): 222–231.doi:10.2307/410515.JSTOR410515.

- Schumacher, Stefan (2005), "'Langvokalische Perfekta' in indogermanischen Einzelsprachen und ihr grundsprachlicher Hintergrund ", in Meiser, Gerhard; Hackstein, Olav (eds.),Sprachkontakt und Sprachwandel. Akten der XI. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, 17. – 23. September 2000, Halle an der Saale,Wiesbaden: Reichert

- Todd, Malcolm (1992).The Early Germans.Blackwell Publishing.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao; Ding, Qi-Liang; Tao, Huan; Li, Hui (2012)."Comment on" Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa "".Science.335(6069): 657.Bibcode:2012Sci...335..657W.doi:10.1126/science.1207846.ISSN0036-8075.PMID22323803.

Germanic languages in general

[edit]- Fulk, R D (2018).A Comparative Grammar of the Early Germanic Languages.Studies in Germanic Linguistics. Vol. 3. John Benjamin.doi:10.1075/sigl.3.ISBN9789027263131.S2CID165765984.

- Helfenstein, James (1870).A comparative grammar of the Teutonic languages.London: MacMillan and Co.

- König, Ekkehard; van der Auwera, Johan (1994).The Germanic languages.London: Routledge.

Proto-Germanic

[edit]- Orel, Vladimir E.(2003).A Handbook of Germanic Etymology.Brill.ISBN978-90-04-12875-0.

- Ringe, Don (2006).A linguistic history of English: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gothic

- Bennett, William H. (1980).An introduction to the Gothic language.New York: Modern Language Association of America.

- Wright, Joseph C. (1919).Grammar of the Gothic language.London: Oxford University Press.

Old Norse

[edit]- Gordon, E.V. (1927).An introduction to Old Norse.London: Oxford University Press.

- Zoëga, Geir T. (2004).A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic.Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Old English

[edit]- Campbell, A. (1959).Old English grammar.London: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Alistair (1983).Old English Grammar.Clarendon Press.ISBN9780198119432.

- Diamond, Robert E. (1970).Old English grammar and reader.Detroit: Wayne State University Press.ISBN9780814313909.

- Hall, J.R. (1984).A concise Anglo–Saxon dictionary, 4th edition.Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Lass, Roger (1994).Old English: A historical linguistic companion.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lass, Roger; Anderson, John M. (1975).Old English phonology.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C. (1992).A guide to Old English, 5th edition.Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Robinson, Orrin(1992).Old English and its closest relatives.Stanford: Stanford University Press.ISBN9780804714549.

- Wright, Joseph; Wright, Mary Elizabeth (1925).Old English grammar, 3rd edition.London: Oxford University Press.

Old High German

[edit]- Wright, Joseph (1906).An Old High German primer, 2nd edition.Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Waterman, John C. (1976).A history of the German language.Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press.

External links

[edit]- Germanic Lexicon Project

- 'Hover & Hear' pronunciationsArchived8 March 2016 at theWayback Machineof the same Germanic words in dozens of Germanic languages and 'dialects', including English accents, and compare instantaneously side by side

- Bibliographie der Schreibsprachen:Bibliography of medieval written forms of High and Low German and Dutch

- Swadesh lists of Germanic basic vocabulary words(from Wiktionary'sSwadesh-list appendix)

- Germanic languages fragments—YouTube (14:06)