Gloucester Cathedral

| Gloucester Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinity | |

| |

| 51°52′03″N2°14′48″W/ 51.8675°N 2.246667°W | |

| Location | Gloucester,Gloucestershire |

| Country | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | gloucestercathedral |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Dedication | St Peter Holy Trinity |

| Consecrated | 15 July 1100 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Formerlyabbey,dissolved 1540.Cathedralsince 1541. |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building |

| Style | Romanesque,Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1089 |

| Completed | 1482[1] |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 426 ft 6 in (130.00 m) |

| Navelength | 174 ft (53 m)[2] |

| Choir length | 140 ft (43 m)[2] |

| Navewidth | 34 ft (10 m)[2] |

| Width across transepts | 144 ft (44 m) |

| Naveheight | 68 ft (21 m)[2] |

| Choir height | 86 ft (26 m)[2] |

| Number oftowers | 1 |

| Tower height | 225 ft (69 m) |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Gloucester(since 1541) |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Rachel Treweek |

| Dean | Andrew Zihni |

| Precentor | Craig Huxley-Jones |

| Chancellor | Rebecca Lloyd |

| Canon(s) | Nikki Arthy (City Rector) |

| Archdeacon | Hilary Dawson |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Adrian Partington |

| Organist(s) | Jonathan Hope |

| Chapter clerk | Theo Platt (COO) |

| Lay member(s) of chapter | Canon Peter Clark, Canon John Coates, Canon Paul Mason[3][4] |

Listed Building– Grade I | |

| Official name | Cathedral Church of the Holy and Indivisible Trinity |

| Designated | 23 January 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1245952 |

Gloucester Cathedral,formally theCathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinityand formerlySt Peter's Abbey,inGloucester, England,stands in the north of the city near theRiver Severn.It originated with the establishment of aminster,Gloucester Abbey, dedicated toSaint Peterand founded byOsric,King of theHwicce,in around 679.

The subsequent history of the church is complex; Osric's foundation came under the control of theBenedictine Orderat the beginning of the 11th century and in around 1058,Ealdred,Bishop of Worcester,established a new abbey "a little further from the place where it had stood". The abbey appears not to have been an initial success, by 1072, the number of attendant monks had reduced to two. The present building was begun by AbbottSerloin about 1089, following a major fire the previous year.

Serlo's efforts transformed the abbey's fortunes; rising revenues and royal patronage enabled the construction of a major church.William the Conquerorheld his Christmas Court at thechapter housein 1085, at which he ordered the compilation ofDomesday Book.In October 1216,Henry IIIwascrownedat the abbey.

Following another disastrous fire in 1222, an ambitious rebuilding programme was begun. In the 14th century, the Great and LittleCloisterswere constructed, displaying the earliest, and perhaps the finest, examples offan vaultinganywhere. The cathedral contains theshrineof deposed KingEdward II,who was believed to have been murdered at nearbyBerkeley Castle.

Following thedissolution of the monasteriesbyHenry VIIIin 1536, the abbey was refounded as a cathedral. The cathedral underwent much restoration in the 18th century, and again in the 19th. In 1989, it celebrated its 900th anniversary. In 2015, the installation ofRachel Treweeksaw theChurch of Englandappoint its first woman as adiocesan bishop.The cathedral has frequently been used as a filming location, including as a stand-in forHogwartsin theHarry Potter movies.

The cathedral is aGrade I listed building.There are a large number of other listed buildings within the cathedral complex, many also listed at Grade I, the highest grade. These include theTreasury,theChapter House,theCloisters,the precinct wall and a number of the medieval gates into the cathedral enclosure. Others are listed at Grade II* and Grade II.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The first recorded religious building on the site was a minster founded byOsric of Hwiccein around 679.[5]A relative, Kyneburg, was consecrated as the first abbess byBosel,Bishop of Worcester.Monastic life flourished, and the possessions of the house increased, but after 767 it seems probable that the nuns dispersed during the confusion of civil strife in England.

Beornwulf of Merciais said to have rebuilt the church, and to have endowed a body of secular priests with the former possessions of the nuns.[6]In 1022Wulfstan,Bishop of Worcester, had theBenedictine ruleintroduced and the abbey dedicated to St Peter.[7]

The early building history is confused; at some point in the early 11th century the monastic buildings were destroyed by fire, and it is recorded thatEaldred,Bishop of Worcesterrebuilt the church in around 1058 on a site "a little further from the place where it stood, and nearer to the side of the city".[8][a]The foundations of the present church were laid by AbbotSerlo(1072–1104).[5]Appointed byWilliam the Conquerorin 1072, Serlo found a new building with a complement of only two monks and eight novices.[10]

The situation was worsened by another major fire in 1088.[5]But the town retained its importance as a favoured royal seat; William celebrated Christmas there in 1085 when, in discussion with hisWitanin thechapter house,he initiated the assembly ofDomesday Book.[10]His support, together with that of others such asWalter de Lacyand his wife,[b]enabled Serlo to embark on a major rebuilding, and between the laying of the foundation stone in 1089 and the abbey's re-consecration in 1100, work on thenave,theapse,thecryptand the chapter house was undertaken at speed[5]and on an "exceptional scale".[12]

St Peter's Abbey had long enjoyed important royal connections, from its foundation, then under the patronage of the Conqueror, and in October 1216 it was chosen as the venue for thecoronationofHenry III,after the death of his father,King John.[13]The nine-year old boy was crowned in the presence of his motherIsabella,whose bracelet was reputedly used in place of a crown.[5]

The abbey's royal connections continued, albeit in a darker vein, in the following century. In 1327,Edward IIwas buried in an elaborateshrineat Gloucester, following his death atBerkeley Castlenearby. Widely believed to have been murdered,[12]Edward was entombed at Gloucester in a lavish ceremony attended by his widow,Isabellaand their young son,Edward.The abbey reputedly benefitted from substantial gifts donated by those making pilgrimage to Edward's shrine, although this is disputed.Nikolaus Pevsnersuggests that the more likely source of revenue was the new king, making donationsin piam memoriam.[14]

Others support the traditional claim, and Jon Cannon, in his work,Cathedral: The great English cathedrals and the world that made them,is certain that the presence of the body of the dead king had a long-term, beneficial, impact on the abbey's fortunes, citingHenry VIII's later decision to make it a cathedral, on account of the presence of "many famous monuments of our renowned ancestors, kings of England."[15]

However occasioned, the cathedral's improved financial position enabled another great period of building. This work included the cloisters, with their famed fan vaulting.[16]St Peter's was unusual as a religious foundation in commissioning its own history, theHistoria Monasterii Sancti Petri Gloucestriae.Its author, Walter Frocester (died 1412), became its first mitred abbot in 1381.[17]

Dependencies[edit]

- In 1134, William Fitznorman gave the church ofSt David,Kilpeck, and the Chapel of St Mary at Kilpeck Castle to Gloucester Abbey, and a priory cell was established about 400 yards south east of the church, to house some monks displaced fromLlanthony Prioryby attacks of the Welsh.Kilpeck Prioryclosed in 1422.[18]

- ThePriory of Saints Peter, Paul and GuthlacinHerefordwas a dependency of Gloucester Abbey.[19]

- Ewenny Priorywas founded byMaurice de Londresin 1141. Maurice granted theNormanchurch ofSt. Michaelto theabbeyof St. Peter at Gloucester, together with the church ofSt Brides Majorand the chapel atOgmore"in order that a convent of monks might be formed".[20]

- In 1146 the college of Augustinian canons atStanley St. Leonardwas given to the monastery by Roger de Berkeley III, with the consent of the prior and canons, and became St. Leonard Priory. His grandfather, Roger de Berkeley I, had retired as a monk to St Peter's Abbey around 1091.[21]

Dissolution and recreation[edit]

At its inception, the abbey stood in thesee of Worcester;but its position was transformed at theDissolution of the monasteries.Following abolition, Henry VIII created the newDiocese of Gloucesterand on 3 September 1541,[22]the abbey church became its cathedral, withJohn Wakeman,last abbot ofTewkesbury,as its first bishop.[16]The diocese covered the greater part ofGloucestershire,with small parts ofHerefordshireandWiltshire.Although staunchlyRoyalistin its sympathies, the city, and the cathedral, escaped largely unscathed from the tumult of theEnglish Civil Warand plans for complete demolition formulated during theCommonwealthwere not taken forward.[16]

The 18th and 19th centuries saw repeated periods of reconstruction, renovation and rebuilding. Counter to the approach sometimes adopted elsewhere in theVictorian era,the 19th century restorations at Gloucester, firstly by the local architects,Frederick S. WallerandThomas Fulljames,and latterly byGeorge Gilbert Scott,were "on the whole, very tactful" [see box].[23][c]During theSecond World Wara recess in the crypt was used to house theCoronation Chair,which had been moved in August 1939 fromWestminster Abbeyfor safe keeping. The 13th century bog-oak effigy ofRobert Curthosewas placed on the chair and the whole covered by sandbags. The Great East Window was also dismantled and placed in storage.[25]The remainder of the 10,000 sandbags supplied by the Office of Works were used to protect the other monuments in the cathedral, including the tomb of Edward II.[25]

Modern period[edit]

The cathedral celebrated its 900th anniversary in 1989. In 2015Rachel Treweekwas installed as bishop, the first woman to be appointed to adiocesan bishopricin the history of theChurch of England.[26]In September 2016 Gloucester Cathedral joined the Church of England's 'Shrinking the footprint' campaign, intended to reduce the Church of England's carbon emissions by 80% by 2050. The cathedral commissioned asolar arrayon the cathedral roof which is expected to reduce the cathedral's energy costs by 25%.[27]The installation was completed by November 2016, making the 927-year-old cathedral the oldest one in the UK with a solar installation.[28][29]

A redevelopment of an old car park next to the cathedral was finished in 2018, making the car park a green space.[30]

Architecture[edit]

Main building[edit]

The cathedral consists of aNormannave (Walter de Lacyis buried there), with additions in every style ofGothic architecture.It is 420 feet (130 m) long, and 144 feet (44 m) wide, with a fine central tower of the 15th century rising to the height of 225 ft (69 m) and topped by four delicatepinnacles.

The crypt, nave and chapter house date from the late 11th century. The crypt is one of the fourapsidalcathedral crypts in England, the others being atWorcester,WinchesterandCanterbury.The nave was begun in 1089. The church was largely complete by 1100. In the early 12th century, the western towers were added; the south tower collapsed around 1165.

In 1222, a fire damaged the timber roof and several of the monastic buildings. To repair the damage and update the architectural style, an ambitious building campaign was launched, including the revaulting of the nave Early English style (completed 1243); the construction of the central tower (begun 1237); the rebuilding of the collapsed south tower (completed 1246); and the rebuilding of the refectory.[9]

The south aisle was rebuilt in 1318–29. The most notable monument is the canopied shrine ofEdward II of Englandwho was murdered at nearbyBerkeley Castlein 1327. Pilgrimages to the tomb brought a huge influx of cash enabling the rebuilding and redecorating of the south transept (1329–37), the north transept (1368–73), and the choir (1350–77). The Norman choir walls are sheathed in Perpendicular tracery. The multiplication of ribs, liernes and Boss es in the choir vaulting is particularly rich.

The late Decorated Great East window is partly filled with surviving medievalstained glass.When completed in 1350, it was the largest window in existence.[31]One window is said to depict the earliest images of the game ofgolf.This dates from 1350, over 300 years earlier than the earliest image of golf from Scotland.[32]Another image, carved on amisericord,shows people playing a ball game, which has been suggested as one of the earliest images ofmedieval football.[33]

Between the apsidal chapels is a crossLady chapel,and north of the nave are thecloisters,the carrels or stalls for the monks' study and writing lying to the south. In a side-chapel is a monument in colouredbog oakofRobert Curthose,eldest son ofWilliam the Conquerorand a great benefactor of the abbey, who was interred there. Monuments ofWilliam Warburton(Bishop of Gloucester) andEdward Jenner(physician) are also worthy of note. The coronation ofHenry IIIis commemorated in a stained-glass window in the south aisle.[34]

Between 1873 and 1890, and in 1897, the cathedral was extensivelyrestoredbyGeorge Gilbert Scott.The cathedral has forty-six 14th-century misericords and twelve 19th-century replacements by Gilbert Scott. Both types have a wide range of subject matter: mythology, everyday occurrences, religious symbolism and folklore.[35]

-

The Quire with the Great East Window behind - in 1350, when installed, it was the largest window in the world

-

The West Window

-

The Quire's vaulted ceiling

-

The vaulted ceiling of the Nave

-

The Nave from the east

-

Facing west towards the choir, with the organ above

Cloisters and cathedral precincts[edit]

The cloisters at Gloucester are the earliest survivingfan vaultsin England, having been designed between 1351 and 1377 by Thomas de Cantebrugge.[36][d]David Verey and Alan Brooks, in the 2002 revised volume,Gloucestershire 2: The Vale and the Forest of Dean,in thePevsner Buildings of Englandseries, call them "the most memorable in England".[38]The cathedral itself suggests that they form "the first and best example of fan vaulting in the world".[39][e]

The cloisters stand to the north of the cathedral and, along with the cathedral precincts to the north and east, contain a number of listed buildings. The Great Cloister itself is listed at Grade I,[40]as are the Little Cloister[41]and Little Cloister House,[42]the remains of areservoirin the north-west corner of the Great Cloister[43]and a passage from the cloister to the formerInfirmary,[44]the remains of the infirmary itself,[45]and the north Precinct Wall.[46]

The other major structures within the precincts are theChapter houseand theTreasuryandlibrary.They date initially from the 11th century, although they have undergone major reconstruction in subsequent centuries. Both are Grade I listed buildings. The treasury adjoins the main cathedral on its northern side, with the library above it, and the chapter house adjoins the treasury.[47][48]

Other structures in the precincts now form part ofKing's School, Gloucesterincluding: the remains of the Abbott's lodgings[49]and Dulverton House,[50]both listed at Grade II*, and the gymnasium,[51]Dulverton House Coachhouse,[52]Wardle House,[53]Palace Cottage[54]and a set of railings surrounding a playground,[55]all of which are listed at Grade II.

-

The GreatCloister

-

Another view

-

Another view

-

Fan vaulting

-

Exterior

College Green and Miller's Green[edit]

College Green lies to the south and west of the cathedral, forming itscathedral close.[56]It was originally the site of a series of monastic graveyards, but was largely rebuilt in the 18th century when many of the buildings were converted to domestic use.[56]

Miller's Green forms a close to the north of the cathedral and was originally the monastic service court. Both Miller's Green and College Green contain a large number ofListed buildings.

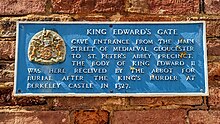

College Green is entered through St Michael's Gate, which dates from the 14th century and is listed at Grade I.[57]No.s 1,[58]2,[59]3,[60]and 4[61]are listed Grade II and stand between St Michael's Gate and King Edward's Gate, which dates from the 16th century, was subject to a major restoration in the 19th century and is listed at II*.[62]No.s 6,[63]7,[64]and 8 conclude the south-western edge of the green and are all listed at Grade II.[65]

No.9 College Green begins the western range of the close and is listed Grade II*.[66]The western range includes No.s 10,[67]11,[68]12, Beaufort House,[69]and 13,[70]all of which are listed at Grade II, and concludes with No. 14, which is listed Grade II*.[71]

The close is then broken by St Mary's Gateway, ascheduled monument.[72]The War Memorial to theRoyal Gloucestershire HussarsYeomanry, a Grade II* listed structure, stands in the centre of College Green.[73]The northern side of College Green concludes with No. 15, Community House, which is Grade II listed,[74]and Church House, which was originally the Abbot's Lodge and is now utilised as offices and a restaurant and is listed at Grade I.[75]On the south-eastern edge of the Green, No.s 17,[76]18[77]and 19[78]are listed at Grade II, while20 College Greenis Grade II*.[79]

Miller's Green is entered through the Inner Gateway, between Community House and No. 7, Miller's Green. The gateway dates from the 14th century and formed thegatehouseto the monastic service court. It is a Grade I listed building,[80]while No. 7 is listed at Grade II.[81]Other buildings on Miller's Green include theDeanery,listed at Grade II*,[82]the Old Mill House, No. 2 Miller's Green, listed at Grade II,[83]and No.s 3,[84]4A,[85]4B,[86]5[87]and 6,[88]all listed at Grade II.

-

No. 9, College Green

-

No. 14, College Green

-

The war memorial on College Green

-

The Deanery, No. 1, Miller's Green

-

The Mediaeval House

Dean and chapter[edit]

- Dean—Andrew Zihni(since 23 April 2023)[89]

- Canon Precentor & Director of Congregational Development — Craig Huxley-Jones (since 23 July 2023 installation)[90]

- Canon Chancellor — Celia Thomson (since 15 March 2003 installation; previously Pastor)[91]

- City Centre Rector (Diocesan Canon) — Nikki Arthy (since 2009; Rector ofSt Mary de Lode,St Mary de CryptandHempsted)

- Archdeacon of Gloucester(Diocesan Canon) —Hilary Dawson(since 27 January 2019 collation)

Music[edit]

Choir[edit]

In medieval times, daily worship was sung by boys and monks from the abbey. The cathedral's current choir was established by KingHenry VIIIin 1539, and at present is composed of 18 boy and 20 girl choristers, as well as 12 adult singers. The choristers attend theKing's School,which was also founded by Henry VIII. The choir sings regularly during term time and at major religious festivals such asChristmasorEaster.It also takes part in concerts and has been featured inchoral evensongonBBC Radio 3.[92]

Organ[edit]

The cathedral's first organ was built by Thomas Harris in 1666. Its original case remains complete, the only such surviving example from the 17th century in England. The pipes displayed on the front of the case are still functional. Over the following four centuries many of the major English organ builders have made contributions to the organ, including modifications in 1847 and a complete rebuild between 1888-1889 byHenry "Father" Willis.[93][94]Harrison & Harrisonundertook a further reconstruction in 1920.[95]

In 1971Hill, Norman and Beard,working with the cathedral's organist John Sanders, and a consultant, Ralph Downes, completely redesigned the instrument, which was again overhauled in 1999 byNicholson & Co.In 2010 Nicholson's added a Trompette Harmonique solo reed.[95]As of 2023, the organ is out of commission, but the cathedral has contracted with Nicholsons for the latest reconstruction to be completed by the time of the next Three Choirs' Festival in 2026.[95]

Organists[edit]

In 1582, Robert Lichfield is recorded as the organist of Gloucester Cathedral. Notable among the organists are composers and choral conductors of theThree Choirs Festival,Herbert Brewer,Herbert SumsionandJohn Sanders.Herbert Howells,who was a pupil of Brewer, composed aMagnificat and Nunc dimittis for Gloucester Cathedral

Three Choirs Festival[edit]

An annual musical festival, theThree Choirs Festival,is hosted by turns in this cathedral and those ofWorcesterandHerefordin rotation.[96]The Three Choirs is the oldest annual musical festival in the world.

Clock and bells[edit]

Clock[edit]

The cathedral's clock, bells and the chimes are referred to in a repair agreement of 1525. The present clock, installed in 1898, is by Dent and Co, who built the clock for Big Ben. There is no external dial, but there is a fine Art Nouveau clock face in the north transept, dating from 1903, designed by Henry Wilson.[97]

Bells[edit]

The bells were rehung and augmented in 1978 to give a ring of twelve. The two oldest bells date from before 1420, so they are older than the present tower. The bells are rung 'full circle' by the cathedral's band of ringers for the weekly practice session In addition there is Great Peter, the largest medieval bell in Britain, weighing a fraction under three tons. Great Peter is the hour bell and can also be heard ringing before the main services.[98]

Burials and monuments[edit]

Gloucester Cathedral has a large collection of funerary monuments from the Middle Ages to the present. Notable people buried at Gloucester Cathedral include:

- Osric, King of the Hwicce

- Robert Curthose,eldest son ofWilliam the Conqueror

- Edward II of England,6thPlantagenetKing of England (1307–1327)

- John Wakeman,lastAbbot of Tewkesburyand firstBishop of Gloucester(1541–1550)

- James Brooks,Bishop of Gloucester (1554–1558)

- Richard Cheyney,Bishop of Gloucester (1562–1579)

- John Bullingham,Bishop of Gloucester (1581–1598)

- Members of theHyett familyfrom the 17th and 18th centuries, whose remains were discovered accidentally in November 2015[99]

- William Nicholson,Bishop of Gloucester (1660–1672)

- Martin Benson,Bishop of Gloucester (1734–1752)

- Richard Pate,landowner andMPfor Gloucester

- Thomas Machen,mercerwho wasmayorof Gloucester three times and one time MP for the city

- Dorothea Beale,Principal of theCheltenham Ladies' College,educational reformer and suffragist

- Ralph Bigland,Garter Principal King of Arms(1712–1784)

- Miles Nightingall,British army general (1768–1829)

- Albert Mansbridge,pioneer ofadult educationin Britain (1876–1952)

- John Yates,Bishop of Gloucester (1925–2008)

-

Tomb ofOsric, King of the Hwicce

-

Tomb ofRobert Curthose

-

Tomb ofEdward II of England

-

Tomb ofThomas Machen

-

Detail of monument to Sarah Morley byJohn Flaxman

Film and television location[edit]

The cathedral has been used as a filming location for movies and for TV including: thefirst,secondandsixthHarry Potter movies;[100]theDoctor WhoepisodesThe Next Doctor[101][102]and theFugitive of the Judoon;[103] The Hollow Crown;[104]Wolf Hall;[105]theSherlockspecialThe Abominable Bride;[106][107]Mary Queen of Scots;[108]and all three ofThe Cousins' Waradaptations–The White Queen,[109]The White Princess[110]andThe Spanish Princess.[111]

Academic use[edit]

Degree ceremonies of theUniversity of Gloucestershireand theUniversity of the West of England(throughHartpury College) both take place at the cathedral.[112][113]The cathedral is also used during school term-time as the venue for assemblies byThe King's School, Gloucester,and for events by theDenmark Road High School,Crypt Grammar School,Sir Thomas Rich's Schoolfor boys andRibston Hall High School.[114]

Timeline[edit]

- 678-79 A small religious community was founded in Anglo-Saxon times byOsric of the Hwicce.His sister Kyneburga was the firstabbess.

- 1017 Secular priests expelled; the monastery given toBenedictinemonks.

- 1072 Serlo, the first Normanabbot,appointed to the almost defunct monastery byWilliam I.

- 1089 Foundation stone of the new abbey church laid byRobert de Losinga,Bishop of Hereford.

- 1100 Consecration of St Peter's Abbey.

- 1216 First coronation ofHenry III.

- 1327 Burial ofEdward II.

- 1331Perpendicularremodelling of thequire.

- 1373 GreatCloister[39]begun by Abbot Horton; completed by Abbott Frouster (1381–1412)

- 1420 West End rebuilt by Abbot Morwent.

- 1450 Tower begun by Abbot Sebrok; completed by Robert Tully.

- 1470 Lady Chapel rebuilt by Abbot Hanley; completed by Abbot Farley (1472–98).

- 1540 Dissolution of the abbey.

- 1541 Refounded as a cathedral byHenry VIII.

- 1616–1621William Laudholds the office of Dean of Gloucester

- 1649–1660 Abolition of dean and chapter, reinstated byCharles II

- 1666 Installation of Great Organ by Thomas Harris

- 1735–1752Martin Benson,Bishop of Gloucester, carried out major repairs and alterations to the cathedral.

- 1847–1873 Beginning of extensiveVictorian restorationwork (Frederick S. WallerandGeorge Gilbert Scott,architects).

- 1953 Major appeal for the restoration of the cathedral; renewed

- 1968 Cathedral largely re-roofed and other major work completed.

- 1989 900th anniversary appeal.

- 1994 Restoration of tower completed.

- 2000 Celebration of the novecentennial of the consecration of St Peter's Abbey.

- 2015 Installation ofRachel Treweekas theChurch of England’s first femalediocesan bishop.[26]

See also[edit]

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- Christopher Whall works in Gloucester Cathedral

Notes[edit]

- ^The history of the early church is made more complicated by its intermingling with that ofSt Oswald's Priory.This foundation was established in around 909 byÆthelflæd,daughter ofAlfred the Great,but was also dedicated to St Peter. Over the following centuries, as the abbey grew in wealth and importance, it incorporated elements of the priory.[9]

- ^On Walter de Lacy's death in 1085, he was buried in the chapter house at Gloucester and his son later became abbot there.[11]

- ^George Gilbert Scott's plans for the restoration ofTewkesbury Abbeysaw a furious assault fromWilliam Morris,who subsequently founded theSociety for the Protection of Ancient Buildingsto fight against the "scraping" he considered was so often the result of Victorian restoration.[24]

- ^Thomas of Catebrugge (of Canterbury) also undertook work atHereford Cathedral.[37]

- ^Gloucester Cathedral also has a LittleCloister,extending from the northeast corner of the Great Cloisters.[39]

References[edit]

- ^Heighway 2003,p. 48.

- ^abcde"Plan of Gloucester Cathedral".Archived fromthe originalon 10 May 2012.Retrieved2 November2015.

- ^"Governance".Gloucester Cathedral Website.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2019.Retrieved28 January2019.

- ^"Appointments".Church Times.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2019.Retrieved28 January2019.

- ^abcdeVerey & Brooks 2002a,p. 395.

- ^Page 1907,pp. 53–61.

- ^Knowles, Brooke & London 1972,p. 52.

- ^Pevsner & Metcalf 2005,p. 100.

- ^abHerbert 1988,pp. 275–288.

- ^abPevsner & Metcalf 2005,p. 101.

- ^Green, Judith A.,The Aristocracy of Norman England.(1997) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 398ISBN0-521-52465-2

- ^abCannon 2011,p. 339.

- ^Ridgeway, Huw W. (2004),"Henry III (1207–1272)",Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.), Oxford University Press (published September 2010),doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12950,archived fromthe originalon 21 September 2013,retrieved22 December2022(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^Pevsner & Metcalf 2005,p. 104.

- ^Cannon 2011,p. 345.

- ^abcVerey & Brooks 2002a,p. 398.

- ^Gransden 2013,p. 391.

- ^Bailey 2000,p.?.

- ^"St Guthlacs Priory".PastScape.org.uk.Historic England.Retrieved15 January2023.

- ^Newman 1995,p. 343.

- ^Cokayne,The Complete Peerage,new edition, II, p.124

- ^Pevsner & Metcalf 2005,p. 106.

- ^Verey & Brooks 2002a,p. 399.

- ^Stamp 2015,pp. 12–13.

- ^abShenton 2021,pp. 201–202.

- ^abWard, Victoria (26 March 2015)."Church of England names first female bishop to sit in the House of Lords".The Daily Telegraph.Retrieved26 March2015.

- ^"Let there be light – 1000 year old Gloucester Cathedral becomes the oldest building of its type in the world to install solar PV".MyPower.Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2018.Retrieved7 September2018.

- ^"First panels laid on 1,000 year old Gloucester Cathedral".Solar Power Portal.Archivedfrom the original on 7 November 2016.Retrieved3 May2021.

- ^"Gloucester Cathedral 'oldest' to get solar panels".BBC. 5 September 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2021.

- ^https:// soglos /news/culture/gloucester-cathedral-celebrates-6-million-project-pilgrim-completion/13181/

- ^"Our heritage - Great East Windwo".Gloucester Cathedral.Retrieved23 December2022.

- ^"The first Golf record?".A Royal and Ancient Golf History video.Fore Tee Video. Archived fromthe originalon 22 January 2009.Retrieved16 January2009.

- ^Flight, Tim (14 November 2019)."40 Unusual Laws in History".History Collection.

- ^Welander 1991,p.?.

- ^"The Misericords and history of Gloucester Cathedral".Misericords.Archivedfrom the original on 9 November 2020.Retrieved3 May2021.

- ^Harvey 1978,p.?.

- ^Pevsner & Metcalf 2005,p. 130.

- ^Verey & Brooks 2002a,p. 425.

- ^abc"The Cloister Project".gloucestercathedral.org.uk.29 September 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2022.Retrieved29 September2022.

- ^Historic England."Cloister and lavatorium (Grade I) (1245954)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Little Cloister (Grade I) (1271578)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Little Cloister House (Grade I) (1271579)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Remains of reservoir, NW corner of cloister (Grade I) (1245955)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Passage from the Cloister to the Infirmary (Grade I) (1271582)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Remains of Monastic Infirmary (Grade I) (1271583)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."North Precinct Wall (Grade I) (1271580)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Cathedral Treasury, Vestry and Library (Grade I) (1245956)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved16 March2023.

- ^Historic England."Cathedral Chapter House (Grade I) (1245953)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved23 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Remains of Abbott's Lodgings (Grade II*) (1245960)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Dulverton House (Grade II*) (1245957)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."King's School Gymnasium (Grade II) (1245961)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Former Coachhouse at Dulverton House (Grade II) (1245958)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Wardle House (Grade II) (1271584)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Palace Cottage (Grade I) (1271581)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Railings to school playground on north side of gymnasium (Grade II) (1271576)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^abVerey & Brooks 2002a,p. 435.

- ^Historic England."St Michael's Gate, College Green (Grade I) (1245905)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."1, College Green (Grade II) (1271593)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."2, College Green (Grade II) (1271594)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."3, College Green (Grade II) (1271595)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."4, College Green (Grade II) (1271596)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."King Edward's Gate, College Green (Grade II*) (1245909)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."6, College Green (Grade II) (1271597)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."7, 7A, 7B, 7C, College Green (Grade II) (1271598)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."8, 8A, College Green (Grade II) (1271599)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."9, College Green (Grade II*) (1271600)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."10, College Green (Grade II) (1271601)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."11, College Green (Grade II) (1271602)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Beaufort House, 12 College Green (Grade II) (1271603)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."13, College Green (Grade II) (1245895)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."14, College Green (Grade II*) (1245896)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."St Mary's Gateway (Grade SM) (1002120)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."War Memorial to the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars Yeomanry (Grade II*) (1245906)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Community House, 15 College Green (Grade II) (1245898)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Church House, 16 College Green (Grade I) (1245900)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."17, College Green (Grade II) (1245901)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."18, College Green (Grade II) (1245902)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."19, College Green (Grade II) (1245903)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."20, College Green (Grade II*) (1245904)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."Inner Gate (Grade I) (1245899)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."7, Miler's Green (Grade II) (1271719)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."The Deanery, 1 Miller's Green (Grade II*) (1271712)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."The Old Mill House, 2 Miller's Green (Grade II) (1271713)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."3, Miller's Green (Grade II) (1271714)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."4A, Miller's Green (Grade II) (1271715)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."4B, Miller's Green (Grade II) (1271716)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."5, Miller's Green (Grade II) (1271717)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^Historic England."6, Miller's Green (Grade II) (1271718)".National Heritage List for England.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^"Zihni installed as the 39th Dean of Gloucester".Gloucester Cathedral.26 April 2023. Archived fromthe originalon 26 April 2023.Retrieved26 April2023.

- ^"Gloucester Cathedral announces new Canon Precentor".Gloucester Cathedral.23 July 2023.Retrieved30 July2023.

- ^"Christ Church West Wimbledon — Information, Candlemas 2003"(PDF).Christchurch-westwimbledon.org.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 23 September 2015.Retrieved9 March2013.

- ^"Gloucester Cathedral | Cathedral Choir".gloucestercathedral.org.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2021.Retrieved8 May2020.

- ^"The National Pipe Organ Register".Npor.org.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2021.Retrieved8 May2020.

- ^"The National Pipe Organ Register".Npor.org.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2021.Retrieved8 May2020.

- ^abc"Gloucester Cathedral – Organ".Gloucestercathedral.org.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2016.Retrieved12 December2016.

- ^"Three Choirs Festival".Archived fromthe originalon 18 April 1999.Retrieved16 January2009.

- ^Verey & Brooks 2002b,p. 23.

- ^"Clock, Bells & Chimes".Gloucester Cathedral.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2019.Retrieved27 October2019.

- ^"Burial vault discovered 'accidentally' at Gloucester Cathedral".BBC News.2 November 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 2 November 2015.Retrieved2 November2015.

- ^"The Harry Potter trail at Gloucester Cathedral".BBC Gloucestershire.Retrieved22 December2022.

- ^"Gloucester Cathedral 'should be heritage site'".BBC Gloucestershire. January 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2018.Retrieved7 September2018.

- ^"Gloucester on film".Thecityofgloucester.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 15 August 2016.

- ^Norris, Phil (21 January 2020)."Doctor Who in Gloucester: This is probably the strangest thing you'll ever see in a cafe".Gloucestershire Live.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2020.Retrieved26 January2020.

- ^"It was a case of 'once more into the breach' for Gloucester Cathedral which has provided the backdrop for another star studded drama".Gloucestershire Live.20 January 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 5 May 2013.Retrieved12 December2016.

- ^"The stately homes of Wolf Hall".BBC News. 7 September 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2018.Retrieved7 September2018.

- ^"Sherlock watch: Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman set for filming in Gloucester Cathedral".Gloucester Citizen. 22 January 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 22 January 2015.Retrieved23 January2015.

- ^"Sherlock stars back filming at Gloucester Cathedral today".Gloucester Citizen. 23 January 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 26 January 2015.Retrieved17 March2015.

- ^Hughes, Janet (15 July 2018)."Spot Gloucester Cathedral in trailer for £180million Margot Robbie blockbuster Mary Queen of Scots".Gloucestershire Live.Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2021.Retrieved10 November2020.

- ^"Gloucester Cathedral Engagement".Gloucester Catherdral Twitter account. 8 April 2020.Retrieved16 March2023.

- ^"Gloucester Cathedral plays host to actors filming 'White Queen' sequel".ITV News. 13 June 2016.Retrieved16 March2023.

- ^"Filmed In Gloucester".Film Gloucester.Retrieved16 March2023.

- ^"University announces honorary awards".University of Gloucestershire.2 September 2016.Retrieved9 July2021.

The graduation ceremonies will take place at Gloucester Cathedral on Thursday November 19 and Friday November 20, 2020

- ^"Hartpury University Graduation".Hartpury University and Hartpury College.Retrieved9 July2021.

Award ceremonies at Gloucester Cathedral on 3–5 November 2021

- ^"G15 Celebration of Success 2018".Make Music Gloucestershire. 5 July 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2019.Retrieved27 October2019.

Sources[edit]

- Bailey, James (2000).The Parish Church of St Mary and St David at Kilpeck.Hereford: Berrington Press.OCLC1033796044.

- Cannon, Jon (2011).Cathedral: The Great English Cathedrals and the World that made them.London:Constable & Robinson.ISBN978-1-849-01679-7.

- Gransden, Antonia (2013).Historical Writing in England: 550 – 1307 and 1307 to the Early Sixteenth Century.London:Routledge.ISBN978-1-136-19021-6.

- Harvey, John (1978).The Perpendicular Style.London:Batsford Books.OCLC819786894.

- Heighway, Carolyn(2003).Gloucester Cathedral and Precinct: an archaeological assessment(PDF).Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.

- Herbert, N.M. (1988). "Gloucester: The cathedral and close".A History of the County of Gloucester.Victoria County History.Vol. 4. Oxford:Oxford University Pressfor theInstitute of Historical Research.OCLC1103213964.

- Knowles, David;Brooke, C. N. L.; London, Vera C. M. (1972).The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales 940–1216.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-08367-2.

- Newman, John(1995).Glamorgan.The Buildings of Wales.London, UK: Penguin.ISBN0140710566.

- Page, William (1907). "The Abbey of St Peter at Gloucester".A History of the County of Gloucester.Victoria County History.Vol. 2. London: Archibald Constable and Company.OCLC927032134.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus;Metcalf, Priscilla (2005).The West and Midlands.The Cathedrals of England. Cambridge:Folio Society.OCLC71807455.

- Shenton, Caroline (2021).National Treasures: Saving the Nation's Art in World War II.London:John Murray.ISBN978-1-529-38743-8.

- Stamp, Gavin(2015).Gothic For The Steam Age: An Illustrated Biography of George Gilbert Scott.London:Aurum Press.ISBN978-1-78131-124-0.OCLC980892536.

- Verey, David; Brooks, Alan (2002a) [1970].Gloucestershire 2: The Vale and the Forest of Dean.The Buildings of England.New Haven, US and London:Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-09733-7.OCLC249275468.

- Verey, David; Brooks, Alan (2002b).Gloucester: The cathedral church of the Holy and Indivisible Trinity.New Haven, US and London:Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-11018-0.

- Welander, David (1991).The history, art, and architecture of Gloucester Cathedral.Stroud, Gloucestershire:Sutton Publishing.OCLC755233912.

Further reading[edit]

External links[edit]

- Gloucester Cathedral

- 681 establishments

- Anglican cathedrals in England

- Benedictine monasteries in England

- Church of England church buildings in Gloucester

- Coronation church buildings

- Diocese of Gloucester

- English Gothic architecture in Gloucestershire

- Grade I listed churches in Gloucestershire

- Grade I listed cathedrals

- Grade I listed buildings in Gloucestershire

- Grade II* listed buildings in Gloucestershire

- Monasteries in Gloucestershire

- English churches with Norman architecture

- Tourist attractions in Gloucestershire

- History of Gloucester

- Pre-Reformation Roman Catholic cathedrals

- Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation

- Anglo-Saxon monastic houses

- Burial sites of the De Lacy family

- Burial sites of the House of Normandy