Gondwanatheria

| Gondwanatheres Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull ofAdalatherium | |

| |

| Mandible ofSudamerica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | †Allotheria(?) |

| Clade: | †Gondwanatheria Mones,1987 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

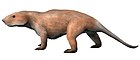

Gondwanatheriais an extinct group ofmammaliaformsthat lived in parts ofGondwana,including Madagascar, India, South America, Africa, and Antarctica during theUpper Cretaceousthrough thePaleogene(and possibly much earlier, ifAllostaffiais a member of this group[3]). Until recently, they were known only from fragmentary remains.[4]They are generally considered to be closely related to themultituberculatesand likely theeuharamiyidians,well known from the Northern Hemisphere, with which they form the cladeAllotheria.[5]

Classification

[edit]

For several decades the affinities of the group were not clear, being first interpreted as earlyxenarthrans,or "toothless" mammals similar to the modernanteater.A variety of studies have placed them asallotheresrelated tomultituberculates,possibly even true multituberculates, closer tocimolodontsthan "plagiaulacidans"are.[1][6][7][8]However, a more recent study recovered them as nested amongharamiyidans,rendering them as non-mammalian cynodonts.[9]A more recently described specimen has since recovered them as allotheres closely related tomultituberculates,[10]but this was soon after followed by a study recovering them as part ofEuharamiyida,which itself was placed inside crown-group Mammalia.[11]

There are three knownfamilieswithin Gondwanatheria. The family Sudamericidae was named by Scillato-Yané and Pascual in 1984, and includes the vast majority of named taxa. The family Ferugliotheriidae was named byJosé Bonapartein 1986, and includes one genus,Ferugliotherium,and possibly a few other forms likeTrapalcotheriumfrom the Late Cretaceous of South America. Ferugliotheriidae are considered the most basal gondawanatherians, and are sometimes recovered outside the group.[5]

Furtherfossilshave come fromIndia,Madagascarand Antarctica. A possibleFerugliotherium-like species occurs inMaastrichtiandeposits ofMexico,extending the clade toNorth America.[12]

The youngest gondwanatherians are known from theEoceneof South America and Antarctica.[13][14]The Eocene genusGroeberiaand Miocene genusPatagonia,two mammals from South America with unusual tooth morphologies usually consideredmetatherians,were considered by one paper to be gondwanatheres.[1]However, their conclusions have generally not been accepted.[5]

Biology

[edit]Gondwanatheres known from cranial remains almost universally have deep, robust snouts, as befitting their specialised herbivorous lifestyle.Vintanapossesses bizarrejugalflanges similar to those ofxenarthranslikeground sloths,though they had a palinal (front-to-back) chewing method as in most allotheres and unlike almost anytherian.[1][6]Most gondwanatheres are specialisedgrazers,even being among the first mammals to have specialised forgrass-eatinglong before any therians did, with the exceptions ofGroeberidaeandFerugliotheriidae,which lack hypsodont teeth and therefore had more generalistic herbivorous habits.

An articulated specimen found in theMaevarano Formationoffers insight to the postcranial skeleton of these animals. Among the bizarre and unique features are a mediolaterally compressed and antero-posteriorly bowed tibia, a doubletrochlea(grooved structure) on thetalus bone,a fully developedhumeral trochlea,and an unusually high number of trunk vertebrae. The new taxon has at least 19 rib-bearing (thoracic) and 11 non-rib-bearing (lumbar) vertebrae. Aside from these derived features, the Malagasy mammal has a mosaic pectoral girdle morphology: the procoracoid is lost, thecoracoidis extremely well developed (into an enlarged process that contributes to half of theglenoid fossa), the interclavicle is small, and thesternoclavicular jointappears mobile. A ventrally-facing glenoid and the well-developed humeral trochlea suggest a relatively parasagittal posture for the forelimbs. Remarkable features of the hind limb and pelvic girdle include a largeobturator foramensimilar in size to that oftherians,a large parafibula, and the presence of anepipubicbone.[15]

The fully described animal, now namedAdalatherium hui,is a comparatively large sized mammal, compared in size to a large cat. It has more erect limbs than other allotheres.[10]

Taxonomy

[edit]Order †Gondwanatheria[16][17]McKenna 1971[GondwanatheroideaKrause & Bonaparte 1993]

- ?†Allostaffia[3]

- †Adalatherium

- ?†Galulatherium

- Family †FerugliotheriidaeBonaparte 1986

- †Ferugliotherium windhauseniBonaparte 1986a[VucetichiaBonaparte 1990;Vucetichia gracilisBonaparte 1990]

- †Trapalcotherium matuastensisRougier et al. 2008

- ?†Magallanodon baikashkenkeGoin et al. 2020

- Family †SudamericidaeScillato-Yané & Pascual 1984[GondwanatheridaeBonaparte 1986]

- †Greniodon sylvanicumGoin et al. 2012

- †Vintana sertichiKrause et al. 2014

- †Dakshina jederiWilson, Das Sarama & Anantharaman 2007

- †Gondwanatherium patagonicumBonaparte 1986

- †Sudamerica ameghinoiScillato-Yané & Pascual 1984

- †Lavanify miolakaKrause et al. 1997

- †Bharattherium bonaparteiPrasad et al. 2007

- †Patagonia peregrinaPascual & Carlini 1987

- †GalulatheriumO'Connor et al. 2019

References

[edit]- ^abcdChimento, Nicolás R.; Agnolin, Federico L.; Novas, Fernando E. (22 April 2014). "The bizarre 'metatherians'GroeberiaandPatagonia,late surviving members of gondwanatherian mammals ".Historical Biology.27(5): 603–623.doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.903945.hdl:11336/85076.S2CID216591096.

- ^Francisco J. Goin; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Laura Chornogubsky; Guillermo M. López; Javier N. Gelfo; Mariano Bond; Michael O. Woodburne; Yamila Gurovich; Marcelo Reguero (2012). "Persistence of a Mesozoic, non-therian mammalian lineage (Gondwanatheria) in the mid-Paleogene of Patagonia".Naturwissenschaften.99(6): 449–463.Bibcode:2012NW.....99..449G.doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0919-z.PMID22584426.S2CID14077735.

- ^abChimento, Nicolas; Agnolin, Federico; Martinelli, Agustin (May 2016)."Mesozoic Mammals from South America: Implications for understanding early mammalian faunas from Gondwana".Historia Evolutiva y Paleobiogeográfica de los Vertebrados de América del Sur.pp. 199–209.

- ^Kraus, David W.(2014).Vintana Sertichi (Mammalia, Gondwanatheria) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar.[Lincoln, NE]: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. pp. 1–2.

- ^abcHoffmann, Simone; Beck, Robin M. D.; Wible, John R.; Rougier, Guillermo W.; Krause, David W. (2020-12-14)."Phylogenetic placement of Adalatherium hui (Mammalia, Gondwanatheria) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar: implications for allotherian relationships".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.40(sup1): 213–234.Bibcode:2020JVPal..40S.213H.doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1801706.ISSN0272-4634.S2CID230968231.

- ^abKrause, David W.; Hoffmann, Simone; Wible, John R.; Kirk, E. Christopher; Schultz, Julia A.; von Koenigswald, Wighart; Groenke, Joseph R.; Rossie, James B.; O'Connor, Patrick M.; Seiffert, Erik R.; Dumont, Elizabeth R.; Holloway, Waymon L.; Rogers, Raymond R.; Rahantarisoa, Lydia J.; Kemp, Addison D.; Andriamialison, Haingoson (5 November 2014). "First cranial remains of a gondwanatherian mammal reveal remarkable mosaicism".Nature.515(7528): 512–517.Bibcode:2014Natur.515..512K.doi:10.1038/nature13922.PMID25383528.S2CID4395258.

- ^"Fossil From Dinosaur Era Reveals Big Mammal With Super Senses".National Geographic News.5 November 2014. Archived fromthe originalon November 5, 2014.

- ^Wilford, John Noble (November 5, 2014)."Fossil's Unusual Size and Location Offer Clues in Evolution of Mammals".New York Times.RetrievedNovember 6,2014.

- ^Huttenlocker, Adam K.; Grossnickle, David M.; Kirkland, James I.; Schultz, Julia A.; Luo, Zhe-Xi (23 May 2018). "Late-surviving stem mammal links the lowermost Cretaceous of North America and Gondwana".Nature.558(7708): 108–112.Bibcode:2018Natur.558..108H.doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0126-y.PMID29795343.S2CID43921185.

- ^abKrause, David W.; Hoffmann, Simone; Hu, Yaoming; Wible, John R.; Rougier, Guillermo W.; Kirk, E. Christopher; Groenke, Joseph R.; Rogers, Raymond R.; Rossie, James B.; Schultz, Julia A.; Evans, Alistair R.; von Koenigswald, Wighart; Rahantarisoa, Lydia J. (29 April 2020). "Skeleton of a Cretaceous mammal from Madagascar reflects long-term insularity".Nature.581(7809): 421–427.Bibcode:2020Natur.581..421K.doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2234-8.PMID32461642.S2CID216650606.

- ^King, Benedict; Beck, Robin M. D. (2020)."Tip dating supports novel resolutions of controversial relationships among early mammals".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.287(1928).doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0943.PMC7341916.PMID32517606.

- ^SVP 2015[full citation needed]

- ^Goin, Francisco J.; Reguero, Marcelo A.; Pascual, Rosendo; Koenigswald, Wighart von; Woodburne, Michael O.; Case, Judd A.; Marenssi, Sergio A.; Vieytes, Carolina; Vizcaíno, Sergio F. (2006-01-01)."First gondwanatherian mammal from Antarctica".Geological Society, London, Special Publications.258(1): 135–144.Bibcode:2006GSLSP.258..135G.doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2006.258.01.10.ISSN0305-8719.S2CID129493664.

- ^Goin, Francisco J.; Tejedor, Marcelo F.; Chornogubsky, Laura; López, Guillermo M.; Gelfo, Javier N.; Bond, Mariano; Woodburne, Michael O.; Gurovich, Yamila; Reguero, Marcelo (2012-06-01). "Persistence of a Mesozoic, non-therian mammalian lineage (Gondwanatheria) in the mid-Paleogene of Patagonia".Naturwissenschaften.99(6): 449–463.Bibcode:2012NW.....99..449G.doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0919-z.ISSN1432-1904.PMID22584426.S2CID14077735.

- ^HOFFMANN, Simone, THE FIRST POSTCRANIAL REMAINS OF A GONDWANATHERIAN MAMMAL, October 2016[verification needed]

- ^Mikko's Phylogeny Archive[1]Haaramo, Mikko (2007)."†Gondwanatheria – gondwanatheres".Retrieved30 December2015.

- ^Paleofile (net, info)"Paleofile".Archived fromthe originalon 2016-01-11.Retrieved2015-12-30.."Taxonomic lists- Mammals".Retrieved30 December2015.