Grammar

| Part ofa serieson |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

Inlinguistics,agrammaris the set of rules for how anatural languageis structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use ofclauses,phrases,andwords.The term may also refer to the study of such rules, a subject that includesphonology,morphology,andsyntax,together withphonetics,semantics,andpragmatics.There are, broadly speaking, two different ways to study grammar:traditional grammarandtheoretical grammar.

Fluency in a particularlanguage varietyinvolves a speaker internalizing these rules, many or most of which areacquiredby observing other speakers, as opposed to intentional study orinstruction.Much of this internalization occurs during early childhood; learning a language later in life usually involves more direct instruction.[1]The termgrammarcan also describe the linguistic behaviour of groups of speakers and writers rather than individuals. Differences in scale are important to this meaning: for example, English grammar could describe those rules followed by every one of the language's speakers.[2]At smaller scales, it may refer to rules shared by smaller groups of speakers.

A description, study, or analysis of such rules may also be known as a grammar, or as agrammar book.Areference workdescribing the grammar of a language is called areference grammaror simply agrammar.A fully revealed grammar, which describes thegrammaticalconstructions of a particular speech type in great detail is called descriptive grammar. This kind oflinguistic descriptioncontrasts withlinguistic prescription,a plan to marginalize some constructions whilecodifyingothers, either absolutely or in the framework of astandard language.The wordgrammaroften has divergent meanings when used in contexts outside linguistics. It may be used more broadly as to includeorthographicconventions ofwritten languagesuch as spelling and punctuation, which are not typically considered as part of grammar by linguists, theconventionsused for writing a language. It may also be used more narrowly to refer to a set ofprescriptive normsonly, excluding the aspects of a language's grammar which do notchangeor are clearly acceptable (or not) without the need for discussions.

Etymology

[edit]The wordgrammaris derived fromGreekγραμματικὴ τέχνη(grammatikḕ téchnē), which means "art of letters", fromγράμμα(grámma), "letter", itself fromγράφειν(gráphein), "to draw, to write".[3]The same Greek root also appears in the wordsgraphics,grapheme,andphotograph.

History

[edit]The first systematic grammar ofSanskritoriginated inIron Age India,withYaska(6th century BC),Pāṇini(6th–5th century BC[4]) and his commentatorsPingala(c. 200 BC),Katyayana,andPatanjali(2nd century BC).Tolkāppiyam,the earliestTamilgrammar, is mostly dated to before the 5th century AD. TheBabyloniansalso made some early attempts at language description.[5]

Grammar appeared as a discipline inHellenismfrom the 3rd century BC forward with authors such asRhyanusandAristarchus of Samothrace.The oldest known grammar handbook is theArt of Grammar(Τέχνη Γραμματική), a succinct guide to speaking and writing clearly and effectively, written by the ancient Greek scholarDionysius Thrax(c.170–c.90 BC), a student of Aristarchus of Samothrace who founded a school on the Greek island of Rhodes. Dionysius Thrax's grammar book remained the primary grammar textbook for Greek schoolboys until as late as the twelfth century AD. The Romans based their grammatical writings on it and its basic format remains the basis for grammar guides in many languages even today.[6]Latin grammardeveloped by following Greek models from the 1st century BC, due to the work of authors such asOrbilius Pupillus,Remmius Palaemon,Marcus Valerius Probus,Verrius Flaccus,andAemilius Asper.

The grammar ofIrishoriginated in the 7th century withAuraicept na n-Éces.Arabic grammaremerged withAbu al-Aswad al-Du'aliin the 7th century. The first treatises onHebrew grammarappeared in theHigh Middle Ages,in the context ofMidrash(exegesis of theHebrew Bible). TheKaraitetradition originated inAbbasidBaghdad.TheDiqduq(10th century) is one of the earliest grammatical commentaries on the Hebrew Bible.[7]Ibn Barunin the 12th century, compares the Hebrew language with Arabic in theIslamic grammatical tradition.[8]

Belonging to thetriviumof the sevenliberal arts,grammar was taught as a core discipline throughout theMiddle Ages,following the influence of authors fromLate Antiquity,such asPriscian.Treatment of vernaculars began gradually during theHigh Middle Ages,with isolated works such as theFirst Grammatical Treatise,but became influential only in theRenaissanceandBaroqueperiods. In 1486,Antonio de NebrijapublishedLas introduciones Latinas contrapuesto el romance al Latin,and the firstSpanish grammar,Gramática de la lengua castellana,in 1492. During the 16th-centuryItalian Renaissance,theQuestione della linguawas the discussion on the status and ideal form of the Italian language, initiated byDante'sde vulgari eloquentia(Pietro Bembo,Prose della volgar linguaVenice 1525). The first grammar ofSlovenewas written in 1583 byAdam Bohorič,andGrammatica Germanicae Linguae,the first grammar of German, was published in 1578.

Grammars of some languages began to be compiled for the purposes of evangelism andBible translationfrom the 16th century onward, such asGrammatica o Arte de la Lengua General de Los Indios de Los Reynos del Perú(1560), aQuechuagrammar byFray Domingo de Santo Tomás.

From the latter part of the 18th century, grammar came to be understood as a subfield of the emerging discipline of modern linguistics. TheDeutsche GrammatikofJacob Grimmwas first published in the 1810s. TheComparative GrammarofFranz Bopp,the starting point of moderncomparative linguistics,came out in 1833.

Theoretical frameworks

[edit]

Frameworks of grammar which seek to give a precise scientific theory of the syntactic rules of grammar and their function have been developed intheoretical linguistics.

- Dependency grammar:dependency relation (Lucien Tesnière1959)

- Functional grammar(structural–functional analysis):

- Montague grammar

Other frameworks are based on an innate "universal grammar",an idea developed byNoam Chomsky.In such models, the object is placed into the verb phrase. The most prominent biologically-oriented theories are:

- Cognitive grammar/Cognitive linguistics

- Generative grammar:

- Transformational grammar(1960s)

- Generative semantics(1970s) andSemantic Syntax(1990s)

- Phrase structure grammar(late 1970s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar(late 1970s)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar(1985)

- Principles and parametersgrammar (Government and binding theory) (1980s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar(late 1970s)

- Lexical functional grammar

- Categorial grammar(lambda calculus)

- Minimalist program-based grammar (1993)

- Stochastic grammar:probabilistic

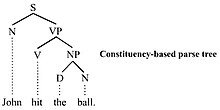

Parse treesare commonly used by such frameworks to depict their rules. There are various alternative schemes for some grammar:

- Affix grammar over a finite lattice

- Backus–Naur form

- Constraint grammar

- Lambda calculus

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- X-bar theory

Development of grammar

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(June 2020) |

Grammars evolve throughusage.Historically, with the advent ofwritten representations,formal rules aboutlanguage usagetend to appear also, although such rules tend to describe writing conventions more accurately than conventions of speech.[11]Formal grammarsarecodificationsof usage which are developed by repeated documentation andobservationover time. As rules are established and developed, the prescriptive concept ofgrammatical correctnesscan arise. This often produces a discrepancy between contemporary usage and that which has been accepted, over time, as being standard or "correct". Linguists tend to view prescriptive grammar as having little justification beyond their authors' aesthetic tastes, although style guides may give useful advice aboutstandard language employmentbased on descriptions of usage in contemporary writings of the same language. Linguistic prescriptions also form part of the explanation for variation in speech, particularly variation in the speech of an individual speaker (for example, why some speakers say "I didn't do nothing", some say "I didn't do anything", and some say one or the other depending on social context).

The formal study of grammar is an important part of children's schooling from a young age through advancedlearning,though the rules taught in schools are not a "grammar" in the sense that mostlinguistsuse, particularly as they areprescriptivein intent rather thandescriptive.

Constructed languages(also calledplanned languagesorconlangs) are more common in the modern-day, although still extremely uncommon compared to natural languages. Many have been designed to aid human communication (for example, naturalisticInterlingua,schematicEsperanto,and the highly logicalLojban). Each of these languages has its own grammar.

Syntaxrefers to the linguistic structure above the word level (for example, how sentences are formed) – though without taking into accountintonation,which is the domain of phonology. Morphology, by contrast, refers to the structure at and below the word level (for example, howcompound wordsare formed), but above the level of individual sounds, which, like intonation, are in the domain of phonology.[12]However, no clear line can be drawn between syntax and morphology.Analytic languagesuse syntax to convey information that is encoded byinflectioninsynthetic languages.In other words, word order is not significant, and morphology is highly significant in a purely synthetic language, whereas morphology is not significant and syntax is highly significant in an analytic language. For example, Chinese andAfrikaansare highly analytic, thus meaning is very context-dependent. (Both have some inflections, and both have had more in the past; thus, they are becoming even less synthetic and more "purely" analytic over time.)Latin,which is highlysynthetic,usesaffixesandinflectionsto convey the same information that Chinese does with syntax. Because Latin words are quite (though not totally) self-contained, an intelligible Latinsentencecan be made from elements that are arranged almost arbitrarily. Latin has a complex affixation and simple syntax, whereas Chinese has the opposite.

Education

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(December 2021) |

Prescriptivegrammar is taught in primary and secondary school. The term "grammar school" historically referred to a school (attached to a cathedral or monastery) that teaches Latin grammar to future priests and monks. It originally referred to a school that taught students how to read, scan, interpret, and declaim Greek and Latin poets (including Homer, Virgil, Euripides, and others). These should not be mistaken for the related, albeit distinct, modern British grammar schools.

Astandard languageis a dialect that is promoted above other dialects in writing, education, and, broadly speaking, in the public sphere; it contrasts withvernacular dialects,which may be the objects of study in academic,descriptive linguisticsbut which are rarely taught prescriptively. The standardized "first language"taught in primary education may be subject topoliticalcontroversy because it may sometimes establish a standard defining nationality orethnicity.

Recently, efforts have begun to updategrammar instructionin primary and secondary education. The main focus has been to prevent the use of outdated prescriptive rules in favor of setting norms based on earlier descriptive research and to change perceptions about the relative "correctness" of prescribed standard forms in comparison to non-standard dialects. A series of metastudies have found that the explicit teaching of grammatical parts of speech and syntax has little or no effect on the improvement of student writing quality in elementary school, middle school of high school; other methods of writing instruction had far greater positive effect, including strategy instruction, collaborative writing, summary writing, process instruction, sentence combining and inquiry projects.[13][14][15]

The preeminence ofParisian Frenchhas reigned largely unchallenged throughout the history of modern French literature. Standard Italian is based on the speech of Florence rather than the capital because of its influence on early literature. Likewise, standard Spanish is not based on the speech of Madrid but on that of educated speakers from more northern areas such as Castile and León (seeGramática de la lengua castellana). InArgentinaandUruguaythe Spanish standard is based on the local dialects of Buenos Aires and Montevideo (Rioplatense Spanish).Portuguesehas, for now,two official standards,Brazilian PortugueseandEuropean Portuguese.

TheSerbianvariant ofSerbo-Croatianis likewise divided;Serbiaand theRepublika SrpskaofBosnia and Herzegovinause their own distinct normative subvarieties, with differences inyatreflexes. The existence and codification of a distinct Montenegrin standard is a matter of controversy, some treatMontenegrinas a separate standard lect, and some think that it should be considered another form of Serbian.

Norwegianhas two standards,BokmålandNynorsk,the choice between which is subject tocontroversy:Each Norwegian municipality can either declare one as its official language or it can remain "language neutral". Nynorsk is backed by 27 percent of municipalities. The main language used in primary schools, chosen by referendum within the local school district, normally follows the official language of its municipality.Standard Germanemerged from the standardized chancellery use ofHigh Germanin the 16th and 17th centuries. Until about 1800, it was almost exclusively a written language, but now it is so widely spoken that most of the formerGerman dialectsare nearly extinct.

Standard Chinesehas official status as the standard spoken form of the Chinese language in the People's Republic of China (PRC), theRepublic of China(ROC), and theRepublic of Singapore.Pronunciation of Standard Chinese is based on the local accent ofMandarin Chinesefrom Luanping, Chengde in Hebei Province near Beijing, while grammar and syntax are based on modernvernacular written Chinese.

Modern Standard Arabicis directly based onClassical Arabic,the language of theQur'an.TheHindustani languagehas two standards,HindiandUrdu.

In the United States, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar designated 4 March asNational Grammar Dayin 2008.[16]

See also

[edit]- Ambiguous grammar

- Constraint-based grammar

- Grammeme

- Harmonic Grammar

- Higher order grammar(HOG)

- Linguistic error

- Linguistic typology

- Paragrammatism

- Speech error(slip of the tongue)

- Usage (language)

- Usus

Notes

[edit]- ^O'Grady, William; Dobrovolsky, Michael; Katamba, Francis (1996).Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction.Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 4–7, 464–539.ISBN978-0-582-24691-1.

- ^Holmes, Janet (2001).An Introduction to Sociolinguistics(2nd ed.). Harlow, Essex: Longman. pp. 73–94.ISBN978-0-582-32861-7.

- ^Harper, Douglas."Grammar".Online Etymological Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 9 March 2013.Retrieved8 April2010.

- ^Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini.Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2017.Retrieved23 October2017.

Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī ( "Eight Chapters" ), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the 6th to 5th century BCE by the Indian grammarian Panini.

- ^McGregor, William B.(2015).Linguistics: An Introduction(2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 15–16.ISBN978-0-567-58352-9.

- ^Casson, Lionel(2001).Libraries in the Ancient World.New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 45.ISBN978-0-300-09721-4.Archivedfrom the original on 24 August 2021.Retrieved11 November2020.

- ^G. Khan, J. B. Noah,The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought(2000)

- ^Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn's Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (1964)

- ^Schäfer, Roland(2016).Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen(2nd ed.). Berlin: Language Science Press.ISBN978-1-5375-0495-7.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2017.Retrieved17 January2020.

- ^Butler, Christopher S. (2003).Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1(PDF).John Benjamins. pp. 121–124.ISBN978-1-58811-358-0.Archived(PDF)from the original on 22 January 2020.Retrieved19 January2020.

- ^Carter, Ronald; McCarthy, Michael (2017). "Spoken Grammar: Where are We and Where are We Going?".Applied Linguistics.38:1–20.doi:10.1093/applin/amu080.

- ^Gussenhoven, Carlos; Jacobs, Haike (2005).Understanding Phonology(2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold.ISBN978-0-340-80735-4.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2021.Retrieved11 November2020.

- ^Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York.Washington, DC:Alliance for Excellent Education.

- ^Graham, Steve; Perin, Dolores (2007)."A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students".Journal of Educational Psychology.99(3): 445–476.CiteSeerX10.1.1.462.2356.doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445.

- ^Graham, Steve; McKeown, Debra; Kiuhara, Sharlene; Harris, Karen R. (2012)."A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades".Journal of Educational Psychology.104(4): 879–896.doi:10.1037/a0029185.

- ^"National Grammar Day".Quick and Dirty Tips.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2021.Retrieved12 November2021.

References

[edit]- Rundle, Bede.Grammar in Philosophy.Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.ISBN0198246129.

External links

[edit]- Grammarfrom theOxford English Dictionary(archived 18 January 2014)

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.).