Gudbrandsdalen

Gudbrandsdalen | |

|---|---|

Dovre,in the northern part of the valley | |

| |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Innlandet |

| Region | Austlandet |

| Urban center | Lillehammer |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,340 km2(5,920 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 71,038 |

| • Density | 4.6/km2(12/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Gudbrandsdøl |

Gudbrandsdalen(Urban East Norwegian:[ˈɡʉ̂ː(d)brɑnsˌdɑːɳ];English:Gudbrand Valley[1][2][3]) is avalleyandtraditional districtin theNorwegiancounty ofInnlandet(formerlyOppland).[4]The valley is oriented in a north-westerly direction fromLillehammerand the lake ofMjøsa,extending 230 kilometers (140 mi) toward theRomsdalenvalley. The riverGudbrandsdalslågen(Lågen) flows through the valley, starting from the lakeLesjaskogsvatnetand ending at the lake Mjøsa. TheOtta riverwhich flows through Otta valley is a major tributary to the main river Lågen. The valleys of the tributary rivers such asOttaand Gausa (Gausdal) are usually regarded as part of Gudbrandsdalen. The total area of the valley is calculated from the areas of the relatedmunicipalities.[5]Gudbrandsdalen is the main valley in a web of smaller valleys. On the western (right hand) side there are long adjacent valleys: Ottadalen stretches 100 kilometers (62 mi) from Otta village, Gausdal some 50 kilometers (31 mi) from Lillehammer andHeidalsome 40 kilometers (25 mi) from Sjoa.[6]Gudbrandsdalen runs between the major mountain ranges of Norway includingJotunheimenandDovrefjell–Rondane.[5]

Together with theGlommariver and theØsterdalenvalley, the river Lågen and the Gudbrandsdalen valley form Norway's largest drainage system covering major parts ofEastern Norway.Gudbrandsdalen is home toDovre Linerailway and theEuropean route E6highway. The valley is the main land transport corridor through Eastern Norway, from Oslo and central eastern lowlands to Trondheim andMøre og Romsdal.

The valley is divided into three parts: Norddalen (Northern valley; themunicipalitiesofLesja,Dovre,Skjåk,Lom,VågåandSel), Midtdalen (middle valley; the municipalities ofNord-Fron,Sør-FronandRingebu), and Sørdalen (Southern valley; the municipalities ofØyer,GausdalandLillehammer). The municipalities within the valley fall under theVestre Innlandet District Court.[5]Until 2016, the valley was also a police district.[7]The Gudbrandsdalen district covers about 60% of the formerOpplandcounty.[6]

The invention of the modern, firm, fatty variant ofBrunost cheeseis commonly attributed to themilkmaidAnne Hovfrom the rural valley.

The main character inHenrik Ibsen's playPeer Gyntwas inspired by a real or legendary person living in the valley in the 18th or 17th century.[8]Ibsen travelled through the valley in 1862 and collected local stories, legends and poems.[9]Ibsen also made drawings from his trip, including "Elstad in Gudbrandsdalen".[6]

Etymology

[edit]

The nameGudbrandsdalenmeans 'the valley/dale of Gudbrand'.Gudbrand(Old NorseGuðbrandr) is an old male name compounded ofguð,'god' andbrandr,'sword'. The name may be derived from a chief (hersir) called Gudbrand. According toSnorri Sturlusonthe district was also referred to asi Dalom( "in the valleys" ) because of the many valleys.[6]Dale-Gudbrandsettled inHundorp,Sør-Fron.[10][11]At the time ofHalfdan the Blackthere was a "chief Gudbrand north in Gubrandsdalen" (Gudbrand herse nord i Dalom). LaterEric Bloodaxehad an opponent called Dale-Gudbrand. According to the sageOlaf II of Norwaymet one Dale-Gudbrand, supposedly the last Dale-Gudbrand, in 1021. Historians believe there was a regional centre at Hundorp during the Viking era and that the name Gudbrand was used for many generations by the ruling family. Burial mounds (tumulus) atHundorpsuggest that powerful men are buried there.[6]

Geography

[edit]The Gudbrandsdalen valley includes the most arid area in Norway. AtSkjåkthe average annual precipitation is only 278 millimetres (10.9 in).[12]The valley sits in therain shadowof the mountains west (includingJotunheimen), north, and east of the valley.[13]The valley is less incised than the valleys of western Norway.[14]Farming is mostly confined to the relatively narrow areas along the rivers. Gudbrandsdalen and adjacent valleys are surrounded by wide uplands and mountain plateaus traditional used asseteror summer farms.[6]

In July 1789 theStorofsenflood disaster occurred and Gudbrandsdalslågen overflooded. This is the largest flood recorded in Norway and the valley was particularly affected. 61 people perished. About 3000 houses were totally damaged and some thousand livestock drowned. All bridges disappeared.[15][16]Lågen rose up to 7 metres (23 ft) above its normal level and covered most of the valley floor.[13]A number of farmers abandoned their damaged farms and settled inMålselv,Tromscounty.[16][15]The second largest flood occurred in the summer of 1995 and again the valley floor was largely covered by water. After Storofsen the valley floor upstream fromSel Churchchanged into bogs and shallow lakes because stone and gravel changed the flow of Lågen. From around 1910 drainage efforts left some 500 hectares (1,200 acres) of dry farmland on what is still known as theSelbogs. The toxiccicuta virosathrived on those bogs before they were drained and are known in Norwegian asselsnepe(literally Selturnip). The valley floor inLesja(between Dombås and Lora) were originally covered by a shallow lake. Drainage efforts from 1860 abolished the lake and left some 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) of farmland.[15]The central part of the valley is covered by theLosnalake, some 50–60 metres (160–200 ft) deep.

Geology

[edit]The valley of Gudbrandsdalen is of considerable antiquity considering the overall development of the relief of Norway. The valley runs across the height axis of the southernScandinavian Mountains—a characteristic that could be indicating that the valley formed before thetectonic uplift of Norway.[14]The valley is one of several valleys ofsouthern Norwaythat existed already as part of the ancientPaleic reliefbut had at the time gentler slopes.[17]Gudbrandsdalen formed and developed originally as a valley of fluvial origin. Only millions of year later was the valley re-shaped byglaciers during the Quaternary period.[14]As the Fennoscandian Ice Sheetmelted and retreatedduring the end of thelast ice agea large but an ephemeralice-dammed lakeformed in the valley.[18]

History

[edit]The valley was shaped by therecent ice ageand rivers from the present glacial areas inJotunheimenandDovre.Bones and teeth frommammothsandmusk oxen,living in the area at that time, are found in the valley. Several traces of hunters from theStone Ageare found in the valley (and in the mountain areas around). There is arock carvingofmoosein the northern part ofLillehammer.[19]Gudbrandsdalen has always hosted the main road between Trondheim and the central eastern lowlands. InOld Norseknown asþjóðvegr(tjodvei), "people's road" or "everybody's road".[6]

Legendary history

[edit]

Raum the Oldwas the father of Dale-Gudbrand, and he settled inHundorp.The Gudbrand Valley is mentioned extensively in theHeimskringla(Chronicle of the Kings of Norway) bySnorri Sturluson.The account ofKing Olaf's (A.D. 1015–1021) conversion of Dale-Gudbrand toChristianityis popularly recognized. According to the saga Gudbrand built a church there "in the valleys", possibly at Haave farm near Hundorp where archaeological evidence indicates what may have been the first church in the valley.[6]In 1206, the heir to theNorwegian throne,Håkon Håkonsson,was saved bybirkebeinerswith a ski-run fromLillehammertoRena.

Until theBlack Plaguesettlement expanded and new farms were established at outskirts. Farms with names-gard,-rud,-hus,and-liare mostly from this expansion period. During theHigh Middle Agesabout 40 churches existed, most built in wood except for instances masonry churches in Easter Gausdal andFollebu.Hamar episcopal see was established in 1152 and its jurisdiction included Gudbrandsdalen.Garmo Stave ChurchandRingebu Stave Churchare examples of ancient wooden churches.Fåvang Stave ChurchandVågå Churchinclude parts from older churches. The Black Plague reduced the population in Gudbrandsdal by 50 to 70% during 1349 to 1350. Saksum, Brekkom, Skåbo, Venabygd and other districts were left largely deserted for centuries. Inhabitants from marginal areas presumably relocated to the main valley and other areas with vacant land. A large number of clergy also perished during the plague and churches fell into disrepair. During the 1600s the population again reached the same level as in 1300. During the 1500s the area had about 6000 inhabitants. No census was taken before 1665 and population figures are based on estimates.[6]This resulted in a temporary improvement for the lower classes ascroftersbecame scarce and the poor were able to rent the better farms.[6]

Older history

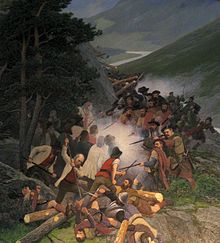

[edit]During theReformationin 1537, theChurch of Norwaywas subordinated to thelendmennor sheriffs. Church property was appropriated by the Crown and the King became the biggest landowner in the valley. TheBattle of Kringentook place in 1612, nearOtta, Norway,and the local "Gudbrandsdøls" defeated aScottishmercenary army. The legends of this battle live on to this day, including the story of how the peasant girlPrillar-Gurilured the Scots into an ambush by playing the traditional ram's horn.[citation needed]The 1665 census indicates a population of 13,000.[6]

In 1670 to 1725, most of the royal property was sold off to pay for war debts, first to established property holders, but increasingly to peasant proprietors. A freeholders' era began and a new "upper class" of landholders was formed.Storofsahappened in 1789, and is the greatest flood recorded in the Gudbrand Valley; several farms were devastated, and many people died.[citation needed]

Modern history

[edit]In 1827, the town ofLillehammeris established. The paddle steamerSkibladneronMjøsaandHovedbanen(the first railroad in Norway) connected the valley to the capital city,Christiania,in 1856. TheHamar-Selbanenrailway was completed toTrettenin 1894. Hamar-Selbanen changed its name to theDovre Linein 1921, and the new main railway betweenOsloandTrondheim,was completed through the valley. The outdoor museum ofMaihaugen,exhibiting historical architecture from all parts of the valley, opened at Lillehammer in 1904.[citation needed]

From around 1865 the population declined substantially because of emigration to North America. Until 1946 the majority of inhabitants worked in farming.[6]

There was severe fighting in the valley atTrettenandKvam,as well as inDombås,duringWorld War II.TheBattle of Dombåswas an attempt to stop theGerman advance.British troops engaged German troops in land battles for the first time in World War 2 after many months ofPhoney War.[20]

Lillehammer was the site of theLillehammer affairin 1973, wherein operatives of theIsraeli Mossadshot and killed a Moroccan waiter they mistakenly thought wasAli Hassan Salameh,who was involved in the Munich Massacre.

The1994 Winter Olympicswere celebrated atLillehammer.

The2016 Youth Olympicswere celebrated at Lillehammer.

Urban areas

[edit]Mountain areas close to the valley

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Jenkins, J. Geraint (1972). "The Use of Artifacts and Folk Art in the Folk Museum". In Dorson, Richard M. (ed.).Folklore and Folklife: An Introduction.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 497–516.

- ^Hesse, David (2014).Warrior Dreams: Playing Scotsmen in Mainland Europe.Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 147.

- ^Art of California.Saint Helena, CA: Greg Saffell Communications. 1990. p. 59.

- ^moderniseringsdepartementet, Kommunal- og (7 July 2017)."Regionreform".Regjeringen.no.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2018.Retrieved28 April2018.

- ^abcThorsnæs, Geir (14 February 2018),"Gudbrandsdalen",Store norske leksikon(in Norwegian),retrieved5 December2018

- ^abcdefghijklGudbrandsdalen.Oslo: Gyldendal, 1974.ISBN8205062846.

- ^"Slik blir politireformen".31 May 2015.

- ^Meyer, Michael. 1974.Ibsen: A Biography.Abridged edition. Pelican Biographies ser. Harmondsworth:Penguin.ISBN0-14-021772-X.

- ^Østvedt, Einar (1967).Med Henrik Ibsen i fjellheimen.Skien: Oluf Rasmussens forlag.

- ^"dialekter i Gudbrandsdalen".snl.no.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^"Gudbrandsdalen".snl.no.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^"Norges våteste og tørreste steder"(in Norwegian). NRK. 11 July 2013.Retrieved21 January2017.

- ^abØstmoe, Arne (1985).Stor-ofsen 1789. Værsystemet som førte til den største flomkatastrofen i Norge(in Norwegian). Ski: Oversiktsregisteret.ISBN82-7379-001-0.

- ^abcBonow, Johan Mauritz;Lidmar-Bergström, Karna;Näslund, Jens-Ove (2007). "Palaeosurfaces and major valleys in the area of Kjølen Mountains, southern Norway – a consequence of uplift and climatic change".Norwegian Journal of Geography.57:83–101.

- ^abcAndersen, Bård (1996).Flomsikring i 200 år.[Oslo]: Norges vassdrags- og energiverk.ISBN82-410-0263-7.

- ^abMardal, Marius A."Storofsen".InGodal, Anne Marit(ed.).Store norske leksikon(in Norwegian). Oslo: Norsk nettleksikon.Retrieved20 September2012.

- ^Lidmar-Bergström, Karna;Ollier, C.D.;Sulebak, J.R. (2000). "Landforms and uplift history of southern Norway".Global and Planetary Change.24(3): 211–231.Bibcode:2000GPC....24..211L.doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00009-6.

- ^Garnes, K.; Bergersten, O.F. (1980). "Wastage features of the inland ice sheet in central South Norway".Boreas.9:251–269.

- ^"Kart - Kulturminnesøk".Kulturminnesøk.

- ^Dirk Levsen: Mikrogeschichte als Besatzungsgeschichte. Der deutsche Feldzug durch das Guldbrandsdal und das Romsdal im Frühjahr 1940. Historiographie und museale Präsentation. In Robert Bohn, (Hrsg.):Die deutsche Herrschaft in den "germanischen" Ländern 1940–1945(= Historische Mitteilungen der Ranke-Gesellschaft, Beiheft 26). Steiner, Stuttgart 1997ISBN3-515-07099-0.S. 113f.