Gus Grissom

Gus Grissom | |

|---|---|

Grissom in 1964 | |

| Born | Virgil Ivan Grissom April 3, 1926 Mitchell, Indiana,U.S. |

| Died | January 27, 1967(aged 40) Cape Canaveral,Florida,U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Education | Purdue University(BS) Air University(BS) |

| Awards | |

| Space career | |

| NASA astronaut | |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel,USAF |

Time in space | 5h 7m |

| Selection | NASA Group 1 (1959) |

| Missions | |

Mission insignia |  |

Virgil Ivan"Gus"Grissom(April 3, 1926 – January 27, 1967) was an American engineer and pilot in theUnited States Air Force,as well as one of the original men, theMercury Seven,selected by theNational Aeronautics and Space AdministrationforProject Mercury,a program to train and launch astronauts intoouter space.Grissom was also aProject GeminiandApollo programastronaut for NASA. As a member of theNASA Astronaut Corps,Grissom was the second American to fly in space in 1961. He was also the second American to fly in space twice, preceded only byJoe Walkerwith his sub-orbitalX-15flights.

Grissom was aWorld War IIandKorean Warveteran, mechanical engineer, andUSAFtest pilot.He was a recipient of theDistinguished Flying Cross,theAir Medalwith anoak leaf cluster,twoNASA Distinguished Service Medals,and, posthumously, theCongressional Space Medal of Honor.

As commander ofAS-204(Apollo 1), Grissom died with astronautsEd WhiteandRoger B. Chaffeeon January 27, 1967, during a pre-launch test for the Apollo 1 mission atCape Kennedy,Florida.

Early life[edit]

Virgil Ivan Grissom was born in the small town ofMitchell, Indiana,on April 3, 1926,[1]to Dennis David Grissom (1903–1994), a signalman for theBaltimore and Ohio Railroad,and Cecile King Grissom (1901–1995), a homemaker. Virgil was the family's second child (an older sister died in infancy shortly before his birth). He was followed by three younger siblings: a sister, Wilma, and two brothers, Norman and Lowell.[2]Grissom started school at Riley grade school. His interest in flying began during that time, building model airplanes.[1]He received his nickname when his friend was reading his name on a scorecard upside down and misread "Griss" as "Gus".[1]

As a youth, Grissom attended the localChurch of Christ,where he remained a lifelong member. He joined the localBoy ScoutTroop and earned the rank ofStar Scout.[3]Grissom credited the Scouts for his love of hunting and fishing. He was the leader of the honor guard in his troop.[4]His first jobs were delivering newspapers forThe Indianapolis Starin the morning and theBedford Timesin the evening.[1]In the summer he picked fruit in area orchards and worked at a dry-goods store.[4]He also worked at a local meat market, a service station, and a clothing store in Mitchell.

Grissom started attendingMitchell High Schoolin 1940.[4]He wanted to play varsity basketball but he was too short. His father encouraged him to find sports he was more suited for, and he joined the swimming team.[4]Although he excelled at mathematics, Grissom was an average high school student in other subjects.[5]He graduated from high school in 1944.

In addition, Grissom occasionally spent time at a local airport inBedford, Indiana,where he first became interested in aviation. A local attorney who owned a small plane would take him on flights and taught him the basics of flying.[6]

World War II[edit]

World War IIbegan while Grissom was still in high school, but he was eager to join the armed services upon graduation. Grissom enlisted as anaviation cadetin theU.S. Army Air Forcesduring his senior year in high school, and completed an entrance exam in November 1943. Grissom was inducted into the U.S. Army Air Forces on August 8, 1944, atFort Benjamin Harrison,Indiana. He was sent toSheppard FieldinWichita Falls, Texas,for five weeks of basic flight training, and was later stationed atBrooks FieldinSan Antonio,Texas. In January 1945 Grissom was assigned toBoca Raton Army Airfieldin Florida. Although he was interested in becoming a pilot, most of Grissom's time before his discharge in 1945 was spent as aclerk.[9]

Post-war employment[edit]

Grissom was discharged from military service in November 1945, after the war had ended, and returned to Mitchell, where he took a job at Carpenter Body Works, a local bus manufacturing business. Grissom was determined to make his career in aviation and attend college. Using theG.I. Billfor partial payment of his school tuition, Grissom enrolled atPurdue Universityin September 1946.[10]

Due to a shortage of campus housing during her husband's first semester in college inWest Lafayette, Indiana,Grissom's wife, Betty, stayed in Mitchell living with her parents, while Grissom lived in a rented apartment with another male student. Betty Grissom joined her husband on campus during his second semester, and the couple settled into a small, one-bedroom apartment. Grissom continued his studies at Purdue, worked part-time as a cook at a local restaurant, and took summer classes to finish college early, while his wife worked the night shift as a long-distance operator for the Indiana Bell Telephone Company to help pay for his schooling and their living expenses. Grissom graduated from Purdue with a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering in February 1950.[11]

Korean War[edit]

After he graduated from Purdue, Grissom re-enlisted in the newly formedU.S. Air Force.He was accepted into theAir Cadet Basic Training ProgramatRandolph Air Force BaseinUniversal City, Texas.Upon completion of the program, he was assigned toWilliams Air Force BaseinMesa, Arizona,where his wife, Betty, and infant son, Scott, joined him, but the family remained there only briefly. In March 1951, Grissom received hispilot wingsand a commission as asecond lieutenant.Nine months later, in December 1951, Grissom and his family moved into new living quarters inPresque Isle, Maine,where he was assigned toPresque Isle Air Force Baseand became a member of the75th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron.[12]

With the ongoingKorean War,Grissom's squadron was dispatched to the war zone in February 1952. There he flew as anF-86 Sabrereplacement pilot and was reassigned to the334th Fighter Squadronof the4th Fighter Interceptor Wingstationed atKimpo Air Base.[13]He flew one hundredcombat missionsduring approximately six months of service in Korea, including multiple occasions when he broke up air raids from North KoreanMiGs.On March 11, 1952, Grissom was promoted tofirst lieutenantand was cited for his "superlative airmanship" for his actions on March 23, 1952, when he flew cover for a photo reconnaissance mission.[14]Grissom was also awarded theDistinguished Flying Crossand theAir Medalwith anoak leaf clusterfor his military service in Korea.[15]

After flying his quota of one hundred missions, Grissom asked to remain in Korea to fly another twenty-five flights, but his request was denied. Grissom returned to the United States to serve as aflight instructoratBryan AFBinBryan, Texas,where he was joined by his wife, Betty, and son, Scott. The Grissoms' second child, Mark, was born there in 1953. Grissom soon learned that flight instructors faced their own set of on-the-job risks. During a training exercise with a cadet, the trainee pilot caused a flap to break off from their two-seat trainer, sending it into a roll. Grissom quickly climbed from the rear seat of the small aircraft to take over the controls and safely land it.[16]

In August 1955, Grissom was reassigned to the U.S.Air Force Institute of Technology(AFIT) atWright-Patterson Air Force BasenearDayton, OhioofAir University.After completing the year-long course he earned abachelor's degreeinaeromechanicsin 1956.[17]In October 1956, he entered theU.S. Air Force Test Pilot SchoolatEdwards Air Force Basein California, and returned to Wright-Patterson AFB inOhioin May 1957, after attaining the rank ofcaptain.Grissom served as atest pilotassigned to the fighter branch.[18][19][20]

NASA career[edit]

In 1959, Grissom received an officialteletypemessage instructing him to report to an address in Washington, D.C., wearing civilian clothes. The message was classified"Top Secret"and Grissom was ordered not to discuss its contents with anyone. Of the 508 military candidates who were considered, he was one of 110 test pilots whose credentials had earned them an invitation to learn more about the U.S. space program in general and itsProject Mercury.Grissom was intrigued by the program, but knew that competition for the final spots would be fierce.[21][22]

Grissom passed the initial screening in Washington, D.C., and was among the thirty-nine candidates sent to theLovelace ClinicinAlbuquerque, New Mexico,and the Aeromedical Laboratory of the Wright Air Development Center in Dayton, Ohio, to undergo extensive physical and psychological testing. He was nearly disqualified when doctors discovered that he suffered fromhay fever,but was permitted to continue after he argued that his allergies would not be a problem due to the absence of ragweed pollen in space.[23]

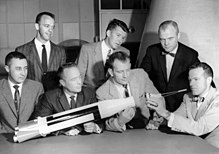

On April 13, 1959, Grissom received official notification that he had been selected as one of the seven Project Mercury astronauts. Grissom and the six other men, after taking a leave of absence from their respective branches of the military service, reported to the Special Task Group atLangley Air Force BaseinVirginiaon April 27, 1959, to begin their astronaut training.[24][25][26]

Project Mercury[edit]

On July 21, 1961, Grissom was pilot of the second Project Mercury flight,Mercury-Redstone 4.Grissom named his spacecraftLiberty Bell 7after theLiberty Bell,and drew a crack on it as a nod to the bell.Liberty Bell 7was launched fromCape Canaveral,Florida, asub-orbital flightthat lasted 15 minutes and 37 seconds.[19][22]Aftersplashdownin the Atlantic Ocean, theLiberty Bell 7's emergency explosive bolts unexpectedly fired, blowing off the hatch and causing water to flood into the spacecraft. Grissom quickly exited through the open hatch and into the ocean. While waiting for recovery helicopters fromUSSRandolphto pick him up, Grissom struggled to keep from drowning after hisspacesuitbegan losing buoyancy due to an open air inlet. Grissom managed to stay afloat until he was pulled from the water by a helicopter and taken to theU.S. Navyship. In the meantime another recovery helicopter tried to lift and retrieve theLiberty Bell 7,but the flooding spacecraft became too heavy, forcing the recovery crew to cut it loose, and it ultimately sank.[22]

When reporters at a news conference surrounded Grissom after his space flight to ask how he felt, Grissom replied, "Well, I was scared a good portion of the time; I guess that's a pretty good indication."[27]Grissom stated he had done nothing to cause the hatch to blow, and no definitive explanation for the incident was found.[22][28]Robert F. Thompson, director of Mercury operations, was dispatched toUSSRandolphbySpace Task GroupDirector Robert Gilruth and spoke with Grissom upon his arrival on the aircraft carrier. Grissom explained that he had gotten ahead in the mission timeline and had removed the detonator cap, and also pulled the safety pin. Once the pin was removed, the trigger was no longer held in place and could have inadvertently fired as a result of ocean wave action, bobbing as a result of helicopter rotor wash, or other activity. NASA officials concluded Grissom had not necessarily initiated the firing of the explosive hatch, which would have required pressing a plunger that required five pounds of force to depress.[29]Hitting this metal trigger with the hand typically left a large bruise,[30]but Grissom was found not to have any of the telltale hand bruising.[22]

While the debate continued about the premature detonation ofLiberty Bell 7's hatch bolts, precautions were initiated for subsequent flights. Fellow Mercury astronautWally Schirra,at the end of hisOctober 3, 1962, flight,remained inside his spacecraft until it was safely aboard the recovery ship, and made a point of deliberately blowing the hatch to get out of the spacecraft, bruising his hand.[22][31]

Grissom's spacecraft wasrecovered in 1999,but no evidence was found that could conclusively explain how the explosive hatch release had occurred. Later,Guenter Wendt,pad leader for the early American crewed space launches, wrote that he believed a small cover over the external release actuator was accidentally lost sometime during the flight or splashdown. Another possible explanation was that the hatch's T-handle may have been tugged by a stray parachute suspension line, or was perhaps damaged by the heat of re-entry, and after cooling upon splashdown it contracted and caught fire.[25][32]It has also been suggested that a static electricity discharge during initial contact between the spacecraft and the rescue helicopter may have caused the hatch's explosive bolts to blow. The co-pilot of the helicopter, U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant John Reinhard, had the job of using a cutting pole to snip off an antenna before the helicopter could latch onto the capsule. In the 1990s, he told a researcher that he remembered seeing an electric arc jump between the capsule and his pole right before the hatch blew.[33]Jim Lewis, the pilot of Grissom's rescue helicopter, toldSmithsonian Magazinethat closer inspection of film footage made him remember the day in better detail. He recalled that "Reinhard must have cut the antenna a mere second or two before I got us in a position for him to attach our harness to the capsule lifting bale," indicating that the timing of the helicopter's approach aligned with the static discharge theory.[34]

Project Gemini[edit]

In early 1964,Alan Shepardwas grounded after being diagnosed withMénière's diseaseand Grissom was designated command pilot forGemini 3,the first crewedProject Geminiflight, which flew on March 23, 1965.[22]This mission made Grissom the first human and thus firstNASA astronautto fly into space twice.[35]The two-man flight on Gemini 3 with Grissom andJohn W. Youngmade three revolutions of the Earth and lasted for 4 hours, 52 minutes and 31 seconds.[36]Grissom was one of the eight pilots of the NASAparaglider research vehicle(Paresev).[37]

Grissom, the shortest of the original seven astronauts at five feet seven inches tall, worked very closely with the engineers and technicians fromMcDonnell Aircraftwho built the Gemini spacecraft. Because of his involvement in the design of the first three spacecraft, his fellow astronauts humorously referred to the craft as "the Gusmobile". By July 1963 NASA discovered 14 out of its 16 astronauts could not fit themselves into the cabin and the later cockpits were modified.[38][39]During this time Grissom invented the multi-axistranslationthruster controller used to push the Gemini and Apollo spacecraft in linear directions forrendezvous and docking.[40]

In a joking nod to the sinking of his Mercury craft, Grissom named the first Gemini spacecraftMolly Brown(after the popular Broadway show,The Unsinkable Molly Brown).[22]Some NASA publicity officials were unhappy with this name and asked Grissom and his pilot,John Young,to come up with a new one. When they offeredTitanicas an alternate,[22]NASA executives decided to allow them to use the name ofMolly Brownfor Gemini 3, but did not use it in official references. Much to the agency's chagrin,CAPCOMGordon Coopergave Gemini 3 its sendoff on launch with the remark to Grissom and Young, "You're on your way,Molly Brown!"Ground controllers also used it to refer to the spacecraft throughout its flight.[41]

After the safe return of Gemini 3, NASA announced new spacecraft would not be nicknamed. Hence,Gemini 4was not calledAmerican Eagleas its crew had planned. The practice of nicknaming spacecraft resumed in 1967, when managers realized that theApolloflights needed a name for each of two flight elements, theCommand Module(CSM) and theLunar Module.Lobbying by the astronauts and senior NASA administrators also had an effect.Apollo 9used the nameGumdropfor the Command Module andSpiderfor the Lunar Module.[42]However, Wally Schirra was prevented from naming hisApollo 7spacecraftPhoenixin honor of theApollo 1crew because some believed that its nickname as a metaphor for "fire" might be misunderstood.[43]

Apollo program[edit]

Grissom was backup command pilot forGemini 6Awhen he was transferred to theApollo programand was assigned as commander of the first crewed mission,AS-204,with Senior PilotEd White,who had flown in space on the Gemini 4 mission, when he became the first American to make aspacewalk,and PilotRoger B. Chaffee.[22]The three men were granted permission to refer to their flight as "Apollo 1" on their mission insignia patch.

Problems with the simulator proved extremely annoying to Grissom, who told a reporter the problems with Apollo 1 came "in bushelfuls" and that he was skeptical of its chances to complete its fourteen-day mission.[44]Grissom earned the nickname "Gruff Gus" by being outspoken about the technical deficiencies of the spacecraft.[45]The engineers who programmed the Apollo training simulator had a difficult time keeping the simulator in sync with the continuous changes being made to the spacecraft. According to backup astronautWalter Cunningham,"We knew that the spacecraft was, you know, in poor shape relative to what it ought to be. We felt like we could fly it, but let's face it, it just wasn't as good as it should have been for the job of flying the first crewed Apollo mission."[22]

NASA pressed on. In mid-January 1967, "preparations were being made for the final pre-flight tests of Spacecraft 012."[22]On January 22, 1967, before returning toCape Kennedyto conduct the January 27 plugs-out test that ended his life, Grissom's wife, Betty, later recalled that he took a lemon from a tree in his back yard and explained that he intended to hang it on that spacecraft, although he actually hung the lemon on the simulator (a duplicate of the Apollo spacecraft).[46][47]

Personal life[edit]

Grissom metBetty Lavonne Moore(1927–2018), in high school.[48]They were married on July 6, 1945, at First Baptist Church in Mitchell when he was home on leave duringWorld War II.The couple had two sons, Scott (1950), and Mark (1953).[49][50]

Two of Grissom's pastimes were hunting and fishing. The family also enjoyed water sports and skiing.[51]

Death[edit]

Before Apollo 1's planned launch on February 21, 1967, the Command Module interior caught fire and burned on January 27, 1967, during a pre-launch test onLaunch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy.Astronauts Grissom, White, and Chaffee, who were working inside the closed Command Module, were asphyxiated. Awaiting launch, Grissom said, "How are we going to get to the Moon if we can't talk between two or three buildings," then shouted "fire!"[52]The fire's ignition source was damaged wiring.[53]The pilots' deaths were attributed to lethal hazards in the early CSM design and conditions of the test, including a pressurized 100 percentoxygenprelaunch atmosphere, wiring and plumbing flaws, flammable materials used in the cockpit and in the astronauts' flight suits, and an inward-opening hatch that could not be opened quickly in an emergency and not at all with full internal pressure.[54]

Grissom's funeral services and burial atArlington National Cemeterywere held on January 31, 1967. Dignitaries in attendance included PresidentLyndon B. Johnson,members of theU.S. Congress,and fellow NASA astronauts, among others. Grissom was interred atArlington National Cemetery,inArlington County, Virginia,[55]beside Roger Chaffee.[56]White's remains are interred at theU.S. Military AcademyatWest Point, New York.[57]

Legacy[edit]

After the accident, NASA decided to give the flight the official designation of Apollo 1 and skip to Apollo 4 for the first uncrewed flight of the Saturn V, counting the two uncrewed suborbital tests,AS-201and202,as part of the sequence. The Apollo spacecraft problems were corrected, withApollo 7,commanded byWally Schirra,launched on October 11, 1968, more than a year and a half after the Apollo 1 accident. The Apollo program reached its objective of successfully landing men on the Moon on July 20, 1969, withApollo 11.[58][59]

At the time of his death, Grissom had attained the rank oflieutenant coloneland had logged a total of 4,600 hours flying time, including 3,500 hours injet airplanes.[19]Some contend that Grissom could have been selected as one of the astronauts to walk on the Moon.Deke Slaytonwrote that he had hoped for one of the original Mercury astronauts to go to the Moon, noting: "It wasn't just a cut-and-dried decision as to who should make the first steps on the Moon. If I had to select on that basis, my first choice would have been Gus, which bothChris KraftandBob Gilruthseconded. "[60]Ultimately,Alan Shepard,one of the original seven NASA astronauts, would receive the honor of commanding theApollo 14lunar landing.[61]

Liberty Bell 7spacesuit controversy[edit]

When theU.S. Astronaut Hall of Fameopened in 1990, his family lent it thespacesuitworn by Grissom duringMercury 4along with other personal artifacts belonging to the astronaut. In 2002, the museum went into bankruptcy and was taken over by a NASA contractor, whereupon the family sought the exhibit's return.[62]All the artifacts were returned to them except the spacesuit, which NASA claimed was government property.[63]NASA insisted Grissom got authorization to use the spacesuit for ashow and tellat his son's school in 1965 and never returned it, but some of Grissom's family members claimed the astronaut rescued the spacesuit from a scrap heap.[64]As of December 2016,[update]the space suit was part of the Kennedy Space Center Hall of Fame's Heroes and Legends exhibit.[65]

Awards and honors[edit]

| ||

To celebrate his spaceflight in 1961, Grissom was made honorary Mayor ofNewport News, Virginia,and a new library was dubbed the Virgil I. Grissom Library in the Denbigh section of Newport News, Virginia.[68]

The airport in Bedford, Indiana, where Grissom flew as a teenager was renamed Virgil I. Grissom Municipal Airport in 1965. A three-ton piece of limestone, inscribed with his name, was unveiled at the airport. His fellow astronauts ribbed him about the name, saying that airports were normally named for dead aviators. Grissom replied, "But this time they've named one for a live one."[69]Virgil Grissom Elementary School in Old Bridge, New Jersey, was named for Grissom the year before his death.[70]His death forced the cancellation of a student project to design a flag to represent Grissom and their school, which would have flown on the mission.[71]

Grissom was awarded theNASA Distinguished Service Medalfor his Mercury flight and was awarded it a second time for his role in Gemini 3.[72]The Apollo 1 crew was awarded the medal posthumously in a 1969 presentation of thePresidential Medal of Freedomto the Apollo 11 crew.[73]

Grissom's family received theCongressional Space Medal of Honorin 1978 from President Carter (White's and Chaffee's families received it in 1997).[74]

Grissom was granted an honorary doctorate fromFlorida Institute of Technologyin 1962, the first-ever awarded by the university.[75]Grissom was inducted into theInternational Space Hall of Famein 1981,[76][77]and theNational Aviation Hall of Famein 1987.[78]Grissom was posthumously inducted into theU.S. Astronaut Hall of Famein 1990.[79][80]His wife,Betty Lavonne Moore,donated his Congressional Space Medal of Honor to the accompanying museum.[81]

Grissom posthumously received AIAA's Haley Astronautics Award for 1968.[82]

Memorials[edit]

If we die, we want people to accept it. We are in a risky business and we hope that if anything happens to us it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life.

The dismantledLaunch Pad 34atCape Canaveral Air Force Stationbears two memorial plaques to the crew of Apollo 1.[84]The Kennedy Space Center features a memorial exhibit honoring the Apollo 1 crew in theApollo/Saturn V Center,which includes artifacts and personal mementos of Grissom, Chaffee, and White. Grissom's name is included on the plaque left on the Moon with theFallen Astronautstatue in 1971 by the crew ofApollo 15.[85]

The Grissom Memorial, a 44-foot (13 m) talllimestonemonument representing the Redstone rocket and his Mercury space capsule was dedicated in downtown Mitchell, Indiana, in 1981.[86]The Virgil I. Grissom Memorial inSpring Mill State Park,near Grissom's hometown of Mitchell, Indiana, was dedicated in 1971, the tenth anniversary of his Mercury flight.[86][87]The governor declared it a state holiday for the second year in a row.[88]TheGus Grissom Stakesis a thoroughbred horse race run in Indiana each fall; originally held atHoosier ParkinAnderson,it was moved toHorseshoe IndianapolisinShelbyvillein 2014.[66]

Grissom Island is anartificial islandoff of Long Beach, California, created in 1966 for drilling oil (along with White, Chaffee andFreemanIslands).[89][90][91]Virgil "Gus" Grissom Park opened in 1971 inFullerton, California.His widow and son were invited to the dedication ceremony and planted the first large tree in the park.[92]Grissom is named with his Apollo 1 crewmates on theSpace Mirror Memorial,which was dedicated in 1991. His son, Gary Grissom, said, "When I was younger, I thought NASA would do something. It's a shame it has taken this long".[93][94]

Navi(Ivanspelled backwards), is a seldom-used nickname for the starGamma Cassiopeiae.Grissom used this name, plus two others for White and Chaffee, on his Apollo 1 mission planning star charts as a joke, and the succeeding Apollo astronauts kept using the names as a memorial.[95][96]Grissom crateris one of several located on the far side of the Moon named for Apollo astronauts. The name was created and used unofficially by the Apollo 8 astronauts and was adopted as the official name by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1970.[97][98]2161 Grissomis amain belt asteroidthat was discovered in 1963 and officially designated in 1981.[99]The name references his launch date of July 21, 1961.[100]Grissom Hill,one of theApollo 1 HillsonMarswas named by NASA on January 27, 2004, the 37th anniversary of the Apollo 1 fire.[101][102]

Bunker Hill Air Force Base in Peru, Indiana, was renamed on May 12, 1968, toGrissom Air Force Base.During the dedication ceremony, his son said, "Of all the honors he won, none would please him more than this one today."[103]In 1994, it was again renamed toGrissom Air Reserve Basefollowing the USAF's realignment program.[104]The three-letter identifier of theVHF Omni Directional Radio Range(VOR) located atGrissom Air Reserve Baseis GUS. In 2000, classes of theUnited States Air Force Academybegan selecting aClass Exemplarwho embodies the type of person they strive to be. The class of 2007 selected Grissom.[105]An academic building was renamed Grissom Hall in 1968 at the formerChanute Air Force Base,Rantoul, Illinois, whereMinuteman missilemaintenance training was conducted. It was one of five buildings renamed for deceased Air Force personnel.[106][107]

The Virgil I. Grissom Museum, dedicated in 1971 by GovernorEdgar Whitcomb,[108]is located just inside the entrance toSpring Mill State Parkin Mitchell, Indiana.[109]TheMolly Brownwas transferred to be displayed in the museum in 1974.[110]His boyhood home in Mitchell, Indiana, is located on Grissom Avenue. The street was renamed in his honor after his Mercury flight.[111][112]

Schools[edit]

Florida Institute of Technologydedicated Grissom Hall, a residence hall, in 1967.[113]State University of New York at Fredoniadubbed their new residence hall Grissom Hall in 1967.[114]Grissom Hall, dedicated in 1968 atPurdue University,was the home of the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics for several decades. It is currently home of the Purdue department of Industrial Engineering.[115][116]

Virgil I. Grissom Elementary School was built in Houston, Texas, in 1967.[117]Virgil Grissom Elementary School in Princeton, Iowa was one of four schools in Iowa named after astronauts in late 1967.[118][119]Grissom's family members attended the 1968 dedication of Virgil I. Grissom Middle School in Mishawaka, Indiana.[120]School No. 7 in Rochester, New York, was named for Grissom in April 1968.[121]Devault Elementary School in Gary, Indiana, was renamed Grissom Elementary School in 1969 after Devault was convicted of conspiring to forge purchase orders.[122]Virgil I. Grissom Middle School was dedicated in November 1969 in Sterling Heights, Michigan.[123]Virgil I. Grissom High Schoolwas built in 1969 in Huntsville, Alabama.[124]The school board in the Hegewisch community of Chicago, Illinois, voted to name their new school under construction Virgil I. Grissom Elementary School in March 1969.[125]Grissom Elementary School in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was founded in 1969[126][127]and dedicated by Betty Grissom in 1970.[128]Grissom Memorial Elementary School was dedicated in 1973 in Muncie, Indiana.[129]Virgil I. Grissom Middle School was founded in Tinley Park, Illinois, in 1975.[130]

Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom Elementary School was operated by the Department of Defense Dependents Schools at the formerClark Air Base,Philippines.[131]Originally named the Wurtsmith Hill School, it was renamed on November 14, 1968.[132]It housed 3rd and 4th grade students. The school was severely damaged by the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991.[133]

- Virgil I. Grissom Junior High School 226, South Ozone Park, Queens, New York City[134]

Film and television[edit]

Grissom has been noted and remembered in many film and television productions. Before he became widely known as an astronaut, the filmAir Cadet(1951) starringRichard LongandRock Hudsonbriefly featured Grissom early in the movie as a U.S. Air Force candidate for flight school atRandolph Field,San Antonio, Texas.[135]Grissom was depicted byFred Wardin the filmThe Right Stuff(1983)[136]and (very briefly) in the filmApollo 13(1995) by Steve Bernie.[137]: 43 He was portrayed in the 1998HBOminiseriesFrom the Earth to the Moon(1998) byMark Rolston.[138]Actor Kevin McCorkle played Grissom in the third-season finale of theNBCtelevision showAmerican Dreams.[139]Bryan Cranstonplayed Grissom as a variety-show guest in the filmThat Thing You Do![140][141]Actor Joel Johnstone portrays Gus Grissom in the 2015ABCTV seriesThe Astronaut Wives Club.[142]In 2016 Gus Grissom was included in the narrative of the movieHidden Figures.In 2018, he was portrayed byShea WhighaminFirst Man.[143]In 2020'sDisney+miniseriesThe Right Stuff,Grissom is portrayed by Michael Trotter.

In the 1984 filmStar Trek III: The Search for Spock,theFederationstarship USS Grissom is named for Grissom.[144]Another USSGrissomwas featured in a 1990 episode of the TV seriesStar Trek: The Next Generation,[145]and was mentioned in a 1999 episode ofStar Trek: Deep Space Nine.[146]The characterGil Grissomin the CBS television seriesCSI: Crime Scene Investigationand the characterVirgil Tracyin the British television seriesThunderbirdsare also named after the astronaut.[147][148]NASA footage, including Grissom's Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions, was released in high definition on theDiscovery Channelin June 2008 in the television seriesWhen We Left Earth: The NASA Missions.[25]

When Grissom died, he was in the process of writing a book about Gemini.[149]

Notes[edit]

- ^The provenance of this quote is uncertain. SeeLeopold 2016,pp. 209–214.

- ^abcdBurgess, Doolan & Vis 2008,p. 88.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 39–40.

- ^"Scouting and Space Exploration".Boy Scouts of America. Archived fromthe originalon March 4, 2016.RetrievedJune 25,2014.

- ^abcdBurgess, Doolan & Vis 2008,p. 89.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 42–43.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 47.

- ^MacKeen, Jason (May 24, 2022)."Famous Freemason - Virgil Grissom".Fellowship Lodge.RetrievedMarch 14,2023.

- ^"Famous Freemasons in History | Freemason Information".February 20, 2009.RetrievedMarch 14,2023.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 48–49.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 50–53.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 55–57.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 57–60.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 63.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 63–68.

- ^Burgess 2014,p. 59.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 68–69.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 71.

- ^"Astronaut Biographies: Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom".U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame.Archived fromthe originalon October 8, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 23,2008.

- ^abcd"Astronaut Bio: Virgil I. Grissom"(PDF).NASA.December 1997.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 9, 2022.RetrievedFebruary 19,2021.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 72–74.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 88–91.

- ^abcdefghijklmWhite, Mary."Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew – Gus Grissom".NASA History Program Office.RetrievedFebruary 21,2017.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 92–93.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 117.

- ^abcDiscovery Channel,When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions,"Ordinary Supermen," airdate June 8, 2008 (season 1)

- ^Zornio, Mary C."Virgil Ivan" Gus "Grissom".NASA History Program Office.RetrievedNovember 16,2014.

- ^"U.S. in Space".Year in Review.UPI.RetrievedJuly 12,2015.

- ^"Liberty Bell 7 Yields Clues to Its Sinking".Los Angeles Times.Archived fromthe originalon March 27, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 29,2017.

- ^Berger, Eric (November 8, 2016)."Gus Grissom taught NASA a hard lesson: 'You can hurt yourself in the ocean'".Ars Technica.RetrievedMarch 26,2017.

- ^French & Burgess 2007,p. 93.

- ^Alexander, C. C.; Grimwood, J. M.; Swenson, L. S. Jr. (1966). "Chapter 14: Climax of Project Mercury-The Textbook Flight".This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury.NASA. p. 484.hdl:2060/19670005605.(HTML copyRetrieved July 12, 2015)

- ^Banke, Jim (June 17, 2000)."Gus Grissom didn't sink the Liberty Bell 7 Mercury capsule".Space.Archived fromthe originalon November 15, 2010.RetrievedFebruary 11,2023.

- ^Leopold, George; Saunders, Andy (July 21, 2021)."Did static electricity — not Gus Grissom — blow the hatch of the Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft?".Astronomy.RetrievedDecember 4,2022.

- ^Reichhardt, Tony."New Evidence Shows That Gus Grissom Did Not Accidentally Sink His Own Spacecraft 60 Years Ago".Smithsonian Magazine.RetrievedDecember 4,2022.

- ^The first person to reach space twice wasJoseph A. Walker,a NASAtest pilotwho made twoX-15flights in 1963 which exceeded 100 kilometers (54 nmi) altitude, the internationally recognized definition of outer space.

- ^"Virgil" Gus "Grissom Honored".Astronaut Memorial Foundation. Archived fromthe originalon July 6, 2017.RetrievedMay 4,2017.

- ^"Photo Paresev Contact Sheet".NASA Dryden Flight Research Center.RetrievedNovember 28,2016.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 100.

- ^Hacker, Barton C.; James M. Grimwood (1977).On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini.NASA History Series #4203. NASA Special Publications. Archived fromthe originalon November 30, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 23,2008.

- ^Agle, D.C. (September 1, 1998),"Flying the Gusmobile",Air & Space,Smithsonian Institution

- ^Shayler 2001,p. 186.

- ^Collins 2001,pp. 138–139.

- ^"Alternate Apollo 7: Astronaut's anniversary patch recalls 'Flight of the Phoenix'".collectSPACE.RetrievedMay 31,2017.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 293.

- ^Burgess, Doolan & Vis 2008,p. 82.

- ^Boomhower 2004,p. 290.

- ^Brooks; Grimwood; Swenson (1979)."Preparations for the First Manned Apollo Mission".Chariots for Apollo.Archivedfrom the original on February 9, 2008.RetrievedApril 22,2016.

- ^Callahan, Rick (October 10, 2018)."Betty Grissom, widow of astronaut Virgil 'Gus' Grissom, dies".Associated Press.RetrievedJanuary 26,2019.

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 59, 68.

- ^"In Memoriam – Lt. Col. Virgil Ivan" Gus "Grissom (USAF)".Archived fromthe originalon July 23, 2014.

- ^"40th Anniversary of Mercury 7: Virgil Ivan" Gus "Grissom".NASA.RetrievedJuly 11,2018.

- ^"File:Apollo One Recording.ogg - Wikipedia".commons.wikimedia.org.January 27, 1967.RetrievedDecember 23,2022.

- ^Sen, Nina (September 4, 2012)."What Happened to NASA's Apollo 1 Mission?".LiveScience.Purch.RetrievedFebruary 11,2021.

- ^"Findings, Determinations And Recommendations".Report of Apollo 204 Review Board.NASA. April 5, 1967. Archived fromthe originalon December 31, 2016.RetrievedJuly 9,2008.

No single ignition source of the fire was conclusively identified.

- ^"Grissom, Virgil Ivan (Section 3, Grave 2503-E)".ANC Explorer.Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- ^"Chaffee, Roger B. (Section 3, Grave 2502-F)".ANC Explorer.Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- ^Boomhower 2004,pp. 315–317.

- ^"The Apollo 1 Tragedy".NASA.RetrievedApril 16,2017.

- ^Dunbar, Brian (January 9, 2018)."Apollo 7".NASA.RetrievedJuly 9,2018.See also:"Apollo 11 Mission Summary".The Apollo Program.Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived fromthe originalon August 29, 2013.RetrievedJuly 9,2018.

- ^Slayton & Cassutt 1994,p. 223.

- ^Slayton & Cassutt 1994,pp. 235–237.

- ^Kelly, John (November 20, 2002)."Gus Grissom's Family, NASA Fight Over Spacesuit".Florida Today.Archived fromthe originalon May 21, 2008.RetrievedMay 27,2007.

- ^"Luckless Gus Grissom in the hot seat again".RoadsideAmerica.November 24, 2002. Archived fromthe originalon September 30, 2007.RetrievedMay 4,2007.

- ^Lee, Christopher (August 24, 2005)."Grissom Spacesuit in Tug of War".The Washington Post.RetrievedMay 27,2007.

- ^Cauley, H. M. (December 8, 2016)."Kennedy Space Center offers new Heroes and Legends hall, much more".The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.RetrievedApril 17,2017.

- ^abcdefghijklBurgess 2014,p. 264.

- ^Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1963: Report of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to the Committee on Science and Astronautics(PDF).Washington, D.C.: U.S. House of Representatives, 89th Congress. 1963.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^Greiff, John B. (July 25, 1961)."Astronaut Grissom is Honorary Mayor, Library Gets Name".Daily Press.Newport News, Virginia. p. 3 – via Newspapers.

- ^Snapp, Raymond (November 20, 1965)."Bedford Airpor Named in Honor of Grissom".The Indianapolis Star.Indianapolis, Indiana. p. 1 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Welcome to Virgil Grissom Elementary School".Old Bridge Township Public Schools.Archived fromthe originalon June 3, 2001.RetrievedJanuary 23,2008.

- ^Heffernan, William (January 28, 1967)."Madison Schools: Living Memorials".The Central New Jersey Home News.New Brunswick, New Jersey. p. 1 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Medal Winners".The Palm Beach Post.Palm Beach, Florida. August 25, 1966. p. 72 – via Newspapers.

- ^Smith, Merriman (August 14, 1969)."Astronauts Awed by the Acclaim".The Honolulu Advertiser.Honolulu, Hawaii. UPI. p. 1 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Congressional Space Medal of Honor".C-SPAN. December 17, 1997.Archivedfrom the original on October 16, 2012.RetrievedJune 16,2016.

- ^Salamon, Milt (January 30, 1997)."1st Astronaut Doctorate Given Locally".Florida Today.Cocoa, Florida. p. 26 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Second American to travel in space; first person to enter space twice".New Mexico Museum of Space History.RetrievedJanuary 27,2019.

- ^Harbert, Nancy (September 27, 1981)."Hall to Induct Seven Space Pioneers".Albuquerque Journal.Albuquerque, New Mexico. p. 53 – via Newspapers.

- ^"National Aviation Hall of fame: Our Enshrinees".National Aviation Hall of Fame.Archived fromthe originalon March 12, 2011.RetrievedFebruary 10,2011.

- ^"Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom".Astronaut Scholarship Foundation.RetrievedJanuary 27,2019.

- ^"Mercury Astronauts Dedicate Hall of Fame at Florida Site".Victoria Advocate.Victoria, Texas. Associated Press. May 12, 1990. p. 38 – via Newspapers.

- ^Clarke, Jay (June 10, 1990)."Astronaut Hall of Fame is Blast from the Past".The Cincinnati Enquirer.Knight News Service. p. 66 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Grissom Named for Posthumous Award".The Bedford Daily-Times Mail.Bedford, Indiana. Associated Press. March 23, 1968. p. 2 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Early Apollo".Apollo to the Moon: To Reach the Moon – Building a Moon Rocket.Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum. July 1999. Archived fromthe originalon May 24, 2011.RetrievedApril 3,2011.

- ^"The Official Site of Edward White, II".Archived fromthe originalon December 3, 2013.RetrievedFebruary 16,2011.

- ^"2 Added Moonshots Called for by Scott".Harford Courant.Hartford, Connecticut. Associated Press. August 13, 1971. p. 5 – via Newspapers.

- ^abTaylor et al. 1989,pp. 335–336.

- ^"Memorial Dedication Today".The Courier-Journal.Louisville, Kentucky. July 21, 1971. p. 40 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Grissom Memorial Dedication at Spring Hill Wednesday".Journal and Courier.Lafayette, Indiana. UPI. July 20, 1971. p. 8 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Oil Biz: A Touch of Disney".The Philadelphia Inquirer.Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Los Angeles Times Service. May 27, 1978. p. 14 – via Newspapers.

- ^Gore, Robert J. (May 19, 1978)."Is This An Apartment Complex...or an Oil Drilling Island?".Tampa Bay Times.St. Petersburg, Florida: Los Angeles Times. p. 14 – via Newspapers.

- ^U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Island Grissom

- ^"Astronaut's Widow Dedicates New Gus Grissom Park".Independent Press-Telegram.Long Beach, California. April 3, 1971. p. 46.

- ^"Hoosier Among Astronauts Honored".Muncie Evening Press.Muncie, Indiana. Associated Press. October 13, 1989. p. 11 – via Newspapers.

- ^Dunn, Marcia (May 10, 1991)."'Space Mirror': Memorial for 15 Dead Astronauts Unveiled at Kennedy Space Center ".Muncie Evening Press.Muncie, Indiana. Associated Press – via Newspapers.

- ^Rao, Joe (September 5, 2008)."Derf, Dnoces, and other strange star names".Space.NBC News.RetrievedJanuary 28,2019.

- ^"Lunar Backside Craters Get Apollo Names".The Fresno Bee.Fresno, California. UPI. December 26, 1968. p. 8 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Grissom".USGS.RetrievedJanuary 28,2019.

- ^"2161 Grissom (1963 UD)".Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).RetrievedJanuary 28,2019.

- ^"Asteroid Named After Grissom".The Tribune.Seymour, Indiana. Associated Press. March 30, 1981. p. 12 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Fallen Apollo 1 astronauts honored on Mars".collectSPACE.RetrievedJanuary 28,2019.

- ^Wallheimer, Brian (October 23, 2007)."Space Experts Say Apollo 1 Deaths Not in Vain".Journal and Courier.Lafayette, Indiana. p. 2.

- ^"Rename Base for Grissom".The South Bend Tribune.South Bend, Indiana. Associated Press. May 13, 1968. p. 4 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Questions About Grissom".Grissom Air Reserve Base, USAF.Archived fromthe originalon November 3, 2007.RetrievedJanuary 23,2008.

- ^"USAFA Class Exemplars".United States Air Force Academy.RetrievedFebruary 25,2019.

- ^"Chanute AFB to Honor Five Heroes on Armed Forces Day".The Pantagraph.Bloomington, Illinois. May 14, 1968. p. 7 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Armed Forces Day at Chanute AF Base".Gibson City Courier.Gibson City, Illinois. May 15, 1975. p. 11 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Grissom Memorial to be Set".The Republic.Columbus, Indiana. July 10, 1971. p. 10 – via Newspapers.

- ^"DNR: Gus Grissom Memorial".Archived fromthe originalon July 24, 2015.RetrievedJuly 24,2015.

- ^"Apollo 15's Module at AF Museum".The Journal Herald.Dayton, Ohio. October 24, 1974. p. 44 – via Newspapers.

- ^Wasik, John W. (April 4, 1965)."Virgil Grissom and John Young: Our Trail-Blazing 'Twin' Astronauts".Family Weekly.The Herald-Tribune. p. 4.RetrievedJanuary 28,2010.

- ^Dibell, Kathie (June 16, 1962)."Welsh, Hovde Head Group Honoring Virgil Grissom".Vidette-Messenger of Porter County.Valparaiso, Indiana. p. 1 – via Newspapers.

- ^"FIT Dedicates 'Grissom Hall'".The Orlando Sentinel.Orlando, Florida. January 31, 1967. p. 16 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Grissom Hall".State University of New York at Fredonia.RetrievedFebruary 28,2019.

- ^Sequin, Cynthia (October 14, 2005)."Purdue industrial engineering kicks off Grissom renovation, celebrates gifts".Purdue University News.RetrievedJanuary 23,2008.

- ^"Grissom, Chaffee Dedications to Honor Fallen Astronauts".Journal and Courier.Lafayette, Indiana. April 26, 1968. p. 14 – via Newspapers.

- ^"Grissom at a Glance".Virgil Ivan Grissom Elementary School.RetrievedFebruary 28,2019.

- ^Lazio, Virginia (November 7, 1967)."Fulton Will Attend N. Scott Dedication".Quad-City Times.p. 3 – via Newspapers.

- ^Bustos, Cheryl (January 29, 1987)."Shuttle Anniversary Touches Student's Hearts".Quad-City Times.Davenport, Iowa. p. 3 – via Newspapers.

- ^Miller, John D. (October 7, 1968)."P-H-M Corp Lauded at Grissom School Dedication".The South Bend Tribune.South Bend, Indiana – via Newspapers.

- ^"Naming of New School No. 7".Democrat and Chronicle.Rochester, New York. April 5, 1968. p. 29 – via Newspapers.

- ^"School Named for Astronaut".The Evening Sun.Baltimore, Maryland. Associated Press. p. 4.

- ^"About Us".Virgil I. Grissom Middle School. Archived fromthe originalon December 3, 2021.RetrievedFebruary 27,2019.

- ^Whitmire, Olivia (August 24, 2018)."Sidewalk on Old Grissom High campus holds 40-year-old memories".WHNT 19 News.RetrievedFebruary 27,2019.

- ^"School Council Plan Reported a Failure".Chicago Tribune.Chicago, Illinois. March 27, 1969. p. 14 – via Newspapers.

- ^"History".Tulsa Public Schools.RetrievedJuly 13,2013.

- ^Kovar, Claudia (September 21, 1994)."Grissom Celebrates 25th Anniversary".Tulsa World.Tulsa, Oklahoma.

- ^"Mrs. Grissom to Aid in School Dedication".The Courier-Journal.Louisville, Kentucky. Associated Press. April 18, 1970. p. 3 – via newspapers.

- ^"Grissom School Dedication is October 28".The Star Press.Muncie, Indiana. October 17, 1973. p. 5 – via Newspapers.

- ^"About Us".Virgil I. Grissom Middle School.RetrievedFebruary 28,2019.

- ^"The History of Clark Air Base Schools".whoa.org.RetrievedApril 3,2019.

- ^Rosmer, David L. (1986)."Table of Contents – An Annotated Pictorial History of Clark Air Base".whoa.org.p. 312.RetrievedApril 3,2019.

- ^Drogin, Bob (June 24, 1991)."Volcano Clouds Future of Strategic Clark Base: Philippines: Mt. Pinatubo may remain active for up to three years, endangering lives and equipment".Los Angeles Times.

- ^Pugh, Thomas (July 2, 1980)."Pupils' D.C. Trip is Memorial to Grissom, Hero Astronaut".Daily News.New York City. p. 782.

- ^Gus GrissomatIMDb

- ^Seelye, Katharine."Betty Grissom, at 91; Husband Died in Apollo Fire".The New York Times.New York. p. C9 – via The Boston Globe.

- ^Rosales, Jean; Jobe, Michael (2003).DC Goes to the Movies: A Unique Guide to the Reel Washington.New York: Writer's Club Press.ISBN978-0-595-26797-2.

- ^Vito & Tropea 2010,p. 195.

- ^Kevin McCorkleatIMDb

- ^Epstein, Leonora (August 26, 2013)."9 of Bryan Cranston's Forgotten Roles".Buzzfeed.RetrievedFebruary 23,2017.

- ^Leopold, Todd (September 19, 2013)."Emmys 2013: Bryan Cranston, man of the moment".CNN.RetrievedApril 28,2018.

- ^"Joel Johnstone Joins ABC's 'The Astronaut Wives Club'; Rahart Adams in Nickelodeon's 'Every Witch Way'".Deadline Hollywood.April 25, 2014.RetrievedFebruary 23,2017.

- ^Jensen, Erin (October 4, 2018)."Christian Bale's 'Vice' co-star Shea Whigham was blown away with Dick Cheney makeover".The Herald-Mail.RetrievedDecember 23,2018.

- ^Okuda, Michael(October 22, 2002).Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Special Collector's Edition: Text commentary(DVD; Disc 1/2).Paramount Pictures.

- ^Roddenberry, Gene (May 1990). "The Most Toys".Star Trek: The Next Generation.Season 3. Episode 22.

- ^Berman, Rick (February 1999). "Field of Fire".Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.Season 7. Episode 13.

- ^Burgess 2015,p. 232.

- ^Gabettas, Chris (Spring 2010)."William Petersen: From ISU to CSI".Idaho State University Magazine.Vol. 20, no. 2. Idaho State University. Archived fromthe originalon April 14, 2013.RetrievedOctober 19,2015.

- ^"Excerpts from Gus Grissom's 'Gemini' Story".The Minneapolis Star.Minneapolis, Minnesota. May 13, 1968. p. 12B – via Newspapers.

References[edit]

- Boomhower, Ray E. (2004).Gus Grissom: The Lost Astronaut.Indiana Biography Series. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.ISBN0-87195-176-2.

- Burgess, Colin;Doolan, Kate; Vis, Bert (2008).Fallen Astronauts: Heroes Who Died Reaching the Moon.Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska.ISBN978-0-8032-1332-6.

- Burgess, Colin (2014).Liberty Bell 7: the suborbital Mercury flight of Virgil I. Grissom.Cham: Springer-Praxis books in space exploration.ISBN978-3-319-04390-6.OCLC868042180.

- Burgess, Colin (2015).Aurora 7: The Mercury Space Flight of M. Scott Carpenter.Springer Praxis Books.ISBN978-3-319-20438-3.

- Collins, Michael (2001).Carrying the Fire: an Astronaut's Journey.Rowman and Littlefield.ISBN978-0-8154-1028-7.

- French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2007).Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961–1965.Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.ISBN978-0-8032-1146-9.

- Leopold, George (2016).Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom.West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press.ISBN978-1-55753-745-4.

- Shayler, David (2001).Gemini: Steps to the Moon.Chichester, United Kingdom: Praxis Publishing.ISBN1-85233-405-3.

- Slayton, Donald K.;Cassutt, Michael(1994).Deke!: U.S. Manned Space from Mercury to the Shuttle.New York City: Forge: St. Martin's Press.ISBN0-312-85503-6.LCCN94-2463.OCLC29845663.

- Taylor, Robert M. Jr.; Stevens, Errol Wayne; Ponder, Mary Ann; Brockman, Paul (1989).Indiana: A New Historical Guide.Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society.ISBN0-87195-048-0.

- Vito, John De; Tropea, Frank (2010).Epic Television Miniseries: A Critical History.Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Company.ISBN978-0-7864-4149-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Bredeson, Carmen (1998).Gus Grissom: A Space Biography.Countdown to Space. Springfield, NJ: Enslow Publishers.ISBN0-89490-974-6.LCCN97-21343.(For children.)

- Greenberger, Robert(2004).Gus Grissom: The Tragedy ofApollo 1.The Library of Astronaut Biographies. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group.ISBN0-8239-4458-1.LCCN2003011980.(For children.)

- Grissom, Virgil I. (1968).Gemini: A Personal Account of Man's Venture into Space.New York: MacMillan Publishing Company.ISBN0-02-545800-0.OCLC442293.

External links[edit]

- Letter from Grissom thanking students for naming their school after him

- Beddingfield, Sam."Astronaut Virgil" Gus "Grissom".SpySpace.Archived fromthe originalon March 28, 2013.RetrievedDecember 19,2007.

- Grissom's Gemini G3-C Pressure Suit,National Air and Space Museum

- Grissom'sLiberty Bell 7Pressure SuitArchivedJune 18, 2019, at theWayback Machine,National Air and Space Museum

- "Gus Grissom Collection, 1960–1967, N.D.",at theIndiana Historical Society,Indianapolis

- "Gus GrissomLiberty Bell 7Flight "ArchivedJuly 30, 2018, at theWayback Machine(video), Sen Corporation, Ltd.

- IHS Staff."Virgil" Gus "Grissom"(PDF).Indiana Historical Society.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 9, 2022.RetrievedJuly 30,2018.

- Virgil (Gus) I. Grissom collectionArchivedJune 18, 2019, at theWayback Machineat the Smithsonian, National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Gus Grissom

- 1926 births

- 1967 deaths

- 1961 in spaceflight

- 1965 in spaceflight

- Apollo 1

- Accidental deaths in Florida

- Air Force Institute of Technology alumni

- American Freemasons

- American test pilots

- American mechanical engineers

- United States Air Force personnel of the Korean War

- Apollo program astronauts

- Aviators from Indiana

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Deaths by smoke inhalation

- Deaths from fire in the United States

- Engineers from Indiana

- Mercury Seven

- Military personnel from Indiana

- National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees

- People from Mitchell, Indiana

- Purdue University College of Engineering alumni

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Recipients of the Congressional Space Medal of Honor

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the NASA Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the NASA Exceptional Service Medal

- U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School alumni

- United States Air Force astronauts

- United States Air Force officers

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II

- United States Astronaut Hall of Fame inductees

- American flight instructors

- Project Gemini astronauts

- United States Army Air Forces soldiers

- People who have flown in suborbital spaceflight