Influenza A virus subtype H5N1

Parts of this article (those related to developments over the last 10 to 15 years) need to beupdated.(January 2024) |

| Influenza A virus | |

|---|---|

| |

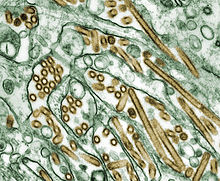

| Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (seen in gold) grown in MDCK cells (seen in green) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | Influenza A virus

|

| Notable strains | |

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1(A/H5N1) is a subtype of theinfluenza A virus,which causesinfluenza(flu), predominantly in birds. It isenzootic(maintained in the population) in many bird populations, and alsopanzootic(affecting animals of many species over a wide area).[1]A/H5N1 virus can also infect mammals (including humans) that have been exposed to infected birds; in these cases, symptoms are frequently severe or fatal.[2]

A/H5N1 virus is shed in the saliva, mucous, and feces of infected birds; other infected animals may shed bird flu viruses in respiratory secretions and other body fluids (such as milk).[3]The virus can spread rapidly through poultry flocks and among wild birds.[3]An estimated half a billion farmed birds have been slaughtered in efforts to contain the virus.[2]

Symptoms of A/H5N1 influenza vary according to both the strain of virus underlying the infection and on the species of bird or mammal affected.[4][5]Classification as either Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) or High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is based on the severity of symptoms in domesticchickensand does not predict the severity of symptoms in other species.[6]Chickens infected with LPAI A/H5N1 virus display mild symptoms or areasymptomatic,whereas HPAI A/H5N1 causes serious breathing difficulties, a significant drop in egg production, and sudden death.[7]

In mammals, including humans, A/H5N1 influenza (whether LPAI or HPAI) is rare. Symptoms of infection vary from mild to severe, including fever, diarrhoea, and cough.[5]Human infections with A/H5N1 virus have been reported in 23 countries since 1997, resulting in severe pneumonia and death in about 50% of cases.[8]As of May 2024, 889 human cases had been identified worldwide, with 463 fatalities, giving acase fatality rateof around 50%;[9]however, it is likely that this may be an overestimate given that mild infections can go undetected and under-reported.[10]

A/H5N1 influenza virus was first identified in farmed birds in southern China in 1996.[11]Between 1996 and 2018, A/H5N1 coexisted in bird populations with other subtypes of the virus, but since then, the highly pathogenic subtype HPAI A(H5N1) has become the dominant strain in bird populations worldwide.[12]Some strains of A/H5N1 which are highly pathogenic to chickens have adapted to cause mild symptoms in ducks and geese,[13][6]and are able to spread rapidly through bird migration.[14]Mammal species that have been recorded with H5N1 infection include cows, seals, goats, and skunks.[15]

Due to the high lethality andvirulenceof HPAI A(H5N1), its worldwide presence, its increasingly diversehostreservoir,and its significant ongoing mutations, the H5N1 virus is regarded as the world's largestpandemicthreat.[16]Domestic poultry may potentially be protected from specific strains of the virus by vaccination.[17]In the event of a serious outbreak of H5N1 flu among humans, health agencies have prepared "candidate" vaccines that may be used to prevent infection and control the outbreak; however, it could take several months to ramp up mass production.[3][18][19]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Humans[edit]

Avian flu viruses, both HPAI and LPAI, can infect humans who are in close, unprotected contact with infected poultry. Incidents of cross-species transmission are rare, with symptoms ranging in severity from no symptoms or mild illness, to severe disease that resulted in death.[22][23]As of February, 2024 there have been very few instances of human-to-human transmission, and each outbreak has been limited to a few people.[24]All subtypes of avian Influenza A have potential to cross the species barrier, withH5N1andH7N9considered the biggest threats.[25][26]

In order to avoid infection, the general public are advised to avoid contact with sick birds or potentially contaminated material such as carcasses or feces. People working with birds, such as conservationists or poultry workers, are advised to wear appropriate personal protection equipment.[27]

The avian influenzahemagglutininprefers to bind to Alpha -2,3sialic acidreceptors, while the human influenza hemagglutinin prefers to bind to Alpha -2,6 sialic acid receptors.[28][29]This means that when the H5N1 strain infects humans, it will replicate in the lower respiratory tract (where Alpha -2,3 sialic acid receptors are more plentiful in humans) and consequently causeviral pneumonia.[30][31]

Between 2003 and May 2024, theWorld Health Organizationhas recorded 892 cases of confirmed H5N1 influenza, leading to 463 deaths.[32]The true fatality rate may be lower because some cases with mild symptoms may not have been identified as H5N1.[33]

Virology[edit]

Influenza virus nomenclature[edit]

To unambiguously describe a specificisolateof virus, researchers use the internationally acceptedInfluenza virus nomenclature,[34]which describes, among other things, the species of animal from which the virus was isolated, and the place and year of collection. For example,A/chicken/Nakorn-Patom/Thailand/CU-K2/04(H5N1):

- Astands for the genus of influenza (A,BorC).

- chickenis the animal species the isolate was found in (note: human isolates lack this component term and are thus identified as human isolates by default)

- Nakorn-Patom/Thailandis the place this specific virus was isolated

- CU-K2is the laboratory reference number that identifies it from other influenza viruses isolated at the same place and year

- 04represents the year of isolation 2004

- H5stands for the fifth of several known types of the proteinhemagglutinin.

- N1stands for the first of several known types of the proteinneuraminidase.

Other examples include: A/duck/Hong Kong/308/78(H5N3), and A/shoveler/Egypt/03(H5N2).[35]

Genetic structure[edit]

H5N1 is a subtype of Influenza A virus, like all subtypes it is anenvelopednegative-senseRNA virus,with a segmented genome.[36]Subtypes of IAV are defined by the combination of the antigenichemagglutininandneuraminidaseproteins in theviral envelope."H5N1" designates an IAV subtype that has a type 5 hemagglutinin (H) protein and a type-1 neuraminidase (N) protein.[37]Further variations exist within the subtypes and can lead to very significant differences in the virus's ability to infect and cause disease, as well as to the severity of symptoms.[38][39]

Influenza viruses have a relatively high mutation rate that is characteristic ofRNA viruses.[40]The segmentation of itsgenomefacilitatesgenetic recombinationby segmentreassortmentin hosts infected with two different strains of influenza viruses at the same time.[41][42]Through a combination ofmutationand geneticreassortmentthe virus can evolve to acquire new characteristics, enabling it to evade host immunity and occasionally to jump from one species of host to another.[43][44]

Prevention and treatment[edit]

Vaccine[edit]

There are several H5N1vaccinesfor several of the avian H5N1 varieties, but the continual mutation of H5N1 renders them of limited use to date: while vaccines can sometimes provide cross-protection against related flu strains, the best protection would be from a vaccine specifically produced for any future pandemic flu virus strain.Daniel R. Lucey,co-director of the Biohazardous Threats and Emerging Diseases graduate program atGeorgetown Universityhas made this point, "There is no H5N1pandemicso there can be no pandemicvaccine".[45]However, "pre-pandemic vaccines" have been created; are being refined and tested; and do have some promise both in furthering research and preparedness for the next pandemic.[46][47][48]Vaccine manufacturing companies are being encouraged to increase capacity so that if a pandemic vaccine is needed, facilities will be available for rapid production of large amounts of a vaccine specific to a new pandemic strain.

Public health[edit]

"TheUnited Statesis collaborating closely with eight international organizations, including theWorld Health Organization(WHO), theFood and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO), theWorld Organization for Animal Health(OIE), and 88 foreign governments to address the situation through planning, greater monitoring, and full transparency in reporting and investigating avian influenza occurrences. The United States and these international partners have led global efforts to encourage countries to heighten surveillance for outbreaks in poultry and significant numbers of deaths in migratory birds and to rapidly introduce containment measures. TheU.S. Agency for International Development(USAID) and theU.S. Department of State,theU.S. Department of Health and Human Services(HHS), andAgriculture(USDA) are coordinating future international response measures on behalf of the White House with departments and agencies across the federal government ".[49]

Together steps are being taken to "minimize the risk of further spread in animal populations", "reduce the risk of human infections", and "further support pandemic planning and preparedness".[49]

Ongoing detailed mutually coordinated onsite surveillance and analysis of human and animal H5N1 avian flu outbreaks are being conducted and reported by theUSGSNational Wildlife Health Center, theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention,theWorld Health Organization,theEuropean Commission,and others.[50]

Treatment[edit]

There is no highly effective treatment for H5N1 flu, butoseltamivir(commercially marketed byRocheas Tamiflu) can sometimes inhibit the influenza virus from spreading inside the user's body. This drug has become a focus for some governments and organizations trying to prepare for a possible H5N1 pandemic.[51]On April 20, 2006, Roche AG announced that astockpileof three million treatment courses ofTamifluare waiting at the disposal of theWorld Health Organizationto be used in case of a flu pandemic; separately Roche donated two million courses to the WHO for use indeveloping nationsthat may be affected by such a pandemic but lack the ability to purchase large quantities of the drug.[52]

However, WHO expert Hassan al-Bushra has said:[53]

Even now, we remain unsure about Tamiflu's real effectiveness. As for avaccine,work cannot start on it until the emergence of a new virus, and we predict it would take six to nine months to develop it. For the moment, we cannot by any means count on a potential vaccine to prevent the spread of a contagious influenza virus, whose various precedents in the past 90 years have been highly pathogenic.

Animal and lab studies suggest that Relenza (zanamivir), which is in the same class of drugs as Tamiflu, may also be effective against H5N1. In a study performed on mice in 2000, "zanamivir was shown to be efficacious in treating avian influenza viruses H9N2,H6N1,and H5N1 transmissible to mammals ".[54]In addition, mice studies suggest the combination of zanamivir, celecoxib and mesalazine looks promising producing a 50% survival rate compared to no survival in the placebo arm.[55]While no one knows if zanamivir will be useful or not on a yet to exist pandemic strain of H5N1, it might be useful to stockpile zanamivir as well as oseltamivir in the event of an H5N1 influenza pandemic. Neither oseltamivir nor zanamivir can be manufactured in quantities that would be meaningful once efficient human transmission starts.[56]In September, 2006, a WHO scientist announced that studies had confirmed cases of H5N1 strains resistant to Tamiflu and Amantadine.[57]Tamiflu-resistant strains have also appeared in theEU,which remain sensitive to Relenza.[58][59]

Epidemiology[edit]

History[edit]

Influenza A/H5N1 was first detected in 1959 after an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza in Scotland, which infected two flocks of chickens.[60][61]The next detection, and the earliest infection of humans by H5N1, was anepizootic(an epidemic in nonhumans) of H5N1 influenza in Hong Kong's poultry population in 1997. This outbreak was stopped by the killing of the entire domestic poultry population within the territory. Human infection was confirmed in 18 individuals who had been in close contact with poultry, 6 of whom died.[62][63]

Since then, avian A/H5N1 bird flu has become widespread in wild birds worldwide, with numerous outbreaks among both domestic and wild birds. An estimated half a billion farmed birds have been slaughtered in efforts to contain the virus.[64][65]

Contagiousness[edit]

H5N1 is easily transmissible between birds, facilitating a potentialglobal spread of H5N1.While H5N1 undergoes mutation and reassortment, creating variations which can infect species not previously known to carry the virus, not all of these variant forms can infect humans. H5N1 as an avian virus preferentially binds to a type ofgalactosereceptors that populate the avian respiratory tract from the nose to the lungs and are virtually absent in humans, occurring only in and around thealveoli,structures deep in the lungs where oxygen is passed to the blood. Therefore, the virus is not easily expelled by coughing and sneezing, the usual route of transmission.[29][30][66]

H5N1 is mainly spread by domesticpoultry,both through the movements of infected birds and poultry products and through the use of infected poultry manure as fertilizer or feed. Humans with H5N1 have typically caught it from chickens, which were in turn infected by other poultry or waterfowl. Migratingwaterfowl(wildducks,geeseandswans) carry H5N1, often without becoming sick.[67][68]Many species of birds and mammals can be infected with HPAI A(H5N1), but the role of animals other than poultry and waterfowl as disease-spreading hosts is unknown.[69]

According to a report by theWorld Health Organization,H5N1 may be spread indirectly. The report stated the virus may sometimes stick to surfaces or get kicked up in fertilizer dust to infect people.[70]

Virulence[edit]

H5N1 hasmutatedinto a variety ofstrainswith differing pathogenic profiles, some pathogenic to one species but not others, some pathogenic to multiple species. Each specific known genetic variation is traceable to a virus isolate of a specific case of infection. Throughantigenic drift,H5N1 has mutated into dozens of highly pathogenic varieties divided into genetic clades which are known from specific isolates, but all belong to genotype Z of avian influenza virus H5N1, now the dominant genotype.[42][41]H5N1 isolates found inHong Kongin 1997 and 2001 were not consistently transmitted efficiently among birds and did not cause significant disease in these animals. In 2002, new isolates of H5N1 were appearing within the bird population of Hong Kong. These new isolates caused acute disease, including severe neurological dysfunction and death inducks.This was the first reported case of lethal influenza virus infection in wild aquatic birds since 1961.[71]

Genotype Z emerged in 2002 throughreassortmentfrom earlier highly pathogenic genotypes of H5N1[72]that first infected birds in China in 1996, and first infected humans inHong Kongin 1997.[41][42][73]Genotype Z is endemic in birds in Southeast Asia, has created at least two clades that can infect humans, and is spreading across the globe in bird populations. Mutations occurring within this genotype are increasing their pathogenicity.[74]Birds are also able to shed the virus for longer periods of time before their death, increasing the transmissibility of the virus.

Pandemic potential[edit]

Influenza viruses have a relatively high mutation rate that is characteristic ofRNA viruses.[75]The segmentation of the influenza A virusgenomefacilitatesgenetic recombinationby segmentreassortmentin hosts who become infected with two different strains of influenza viruses at the same time.[76][77]With reassortment between strains, an avian strain which does not affect humans may acquire characteristics from a different strain which enable it to infect and pass between humans - azoonoticevent.[78]

As of June 2024, there is concern about two subtypes of avian influenza which are circulating in wild bird populations worldwide, A/H5N1 andA/H7N9.Both of these have potential to devastate poultry stocks, and both have jumped to humans with relatively highcase fatality rates.[79]A/H5N1 in particular has infected awide range of mammalsand may be adapting to mammalian hosts.[80]

Surveillance[edit]

TheGlobal Influenza Surveillance and Response System(GISRS)is a global network of laboratories that monitor the spread ofinfluenzawith the aim to provide theWorld Health Organizationwith influenza control information and to inform vaccine development.[81]Several millions of specimens are tested by the GISRS network annually through a network of laboratories in 127 countries. GISRS monitors avian, swine, and other potentiallyzoonoticinfluenza viruses as well as human viruses.[82]

Transmission and host range[edit]

Infected birds transmit H5N1 through theirsaliva,nasal secretions,fecesandblood.Other animals may become infected with the virus through direct contact with these bodily fluids or through contact with surfaces contaminated with them. H5N1 remains infectious after over 30 days at 0 °C (32 °F) (over one month at freezing temperature) or 6 days at 37 °C (99 °F) (one week at human body temperature); at ordinary temperatures it lasts in the environment for weeks. In Arctic temperatures, it does not degrade at all.[citation needed]

Because migratory birds are among the carriers of the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus, it is spreading to all parts of the world. H5N1 is different from all previously known highly pathogenic avian flu viruses in its ability to be spread by animals other than poultry.

In October 2004, researchers discovered H5N1 is far more dangerous than was previously believed.Waterfowlwere revealed to be directly spreading this highly pathogenic strain tochickens,crows,pigeons,and other birds, and the virus was increasing its ability to infect mammals, as well. From this point on, avian flu experts increasingly referred to containment as a strategy that can delay, but not ultimately prevent, a future avian flu pandemic.[citation needed]

"Since 1997, studies of influenza A (H5N1) indicate that these viruses continue to evolve, with changes in antigenicity and internal gene constellations; an expanded host range in avian species and the ability to infect felids; enhanced pathogenicity in experimentally infected mice and ferrets, in which they cause systemic infections; and increased environmental stability."[83]

The New York Times,in an article on transmission of H5N1 through smuggled birds, reports Wade Hagemeijer of Wetlands International stating, "We believe it is spread by both bird migration and trade, but that trade, particularly illegal trade, is more important".[84]

On September 29, 2007, researchers reported the H5N1 bird flu virus can also pass through a pregnant woman's placenta to infect the fetus. They also found evidence of what doctors had long suspected—the virus not only affects the lungs, but also passes throughout the body into the gastrointestinal tract, the brain, liver, and blood cells.[85]

In May 2013,North Koreaconfirmed a H5N1 bird flu outbreak that forced authorities to kill over 160,000 ducks inPyongyang.[86]

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

cases |

deaths |

CFR

|

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 8 | 1 | 12.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 100% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 8 | 8 | 100% | 3 | 3 | 100% | 26 | 14 | 53.8% | 9 | 4 | 44.4% | 6 | 4 | 66.7% | 7 | 1 | 14.0% | 69 | 42 | 60.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 13 | 8 | 61.5% | 5 | 3 | 60.0% | 4 | 4 | 100% | 7 | 4 | 57.1% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 2 | 0 | 0% | 6 | 1 | 16.7% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 55 | 32 | 58.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 10 | 55.6% | 25 | 9 | 36.0% | 8 | 4 | 50.0% | 39 | 4 | 10.3% | 29 | 13 | 44.8% | 39 | 15 | 38.5% | 11 | 5 | 45.5% | 4 | 3 | 75.0% | 37 | 14 | 37.8% | 136 | 39 | 28.7% | 10 | 3 | 30.0% | 3 | 1 | 33.3% | 359 | 120 | 33.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 13 | 65.0% | 55 | 45 | 81.8% | 42 | 37 | 88.1% | 24 | 20 | 83.3% | 21 | 19 | 90.5% | 9 | 7 | 77.8% | 12 | 10 | 83.3% | 9 | 9 | 100% | 3 | 3 | 100% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 200 | 168 | 84.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 2 | 66.6% | 3 | 2 | 66.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 3 | 2 | 66.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 33.3% | 3 | 1 | 33.3% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | 12 | 70.6% | 5 | 2 | 40.0% | 3 | 3 | 100% | 25 | 17 | 68.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 4 | 33.3% | 12 | 4 | 33.3% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 4 | 0 | 0% | 5 | 0 | 0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 7 | 0 | 0% | 8 | 0 | 0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 100% | 29 | 20 | 69.0% | 61 | 19 | 31.1% | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 6 | 5 | 83.3% | 5 | 5 | 100% | 7 | 2 | 28.6% | 4 | 2 | 50.0% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 129 | 65 | 50.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 100% | 46 | 32 | 69.6% | 98 | 43 | 43.9% | 115 | 79 | 68.7% | 88 | 59 | 67.0% | 44 | 33 | 75.0% | 73 | 32 | 43.8% | 48 | 24 | 50.0% | 62 | 34 | 54.8% | 32 | 20 | 62.5% | 39 | 25 | 64.1% | 52 | 22 | 42.3% | 145 | 42 | 29.0% | 10 | 3 | 30.0% | 4 | 2 | 50.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 6 | 1 | 16.7% | 12 | 4 | 33.3% | 16 | 2 | 12.5% | 898 | 463 | 51.6% |

2020–2024 global H5N1 outbreak[edit]

Europe[edit]

A major outbreak of a new strain of H5N1 in wild birds and poultry appeared in Russia in August 2020 and quickly spread to other parts of Europe by October.[87]

Over the winter of 2021 and 2022, avian flu spread among the population ofbarnacle geeseon the Solway Firth, UK, with estimates of up to a third of the Svalbard population being lost;[88][89]pink-footed geesewere also affected there and it seems carried the virus to new sites in northern Scotland. The disease was confirmed insandwich ternsin South Africa in April 2022.[90]In late spring 2022 avian flu outbreaks affected many species of wild bird in the United Kingdom, with heavy losses reported among seabirds returning to breed at colonies in the Northern Isles and Outer Hebrides,[91]includinggreat skuas(bonxie) for which outbreaks had initially been reported in 2021[92](Scotland hosts c. 60% of the world's breeding population) – the 2022 census onSt Kildashowed a 64% decline on 2019 with 106 dead birds recorded so far (to 6 June),[93]gannets(1000+ birds reported dead at the Shetlands'Hermanesscolony alone,[91]where there are around 26,000 breeding pairs), with many more gannets being reported dead at other colonies (Troup Head,Bass Rock,andSt Kilda);[94]the range of species also seems to be expanding, with reports for many species of wildfowl, seabirds (auks, terns and gulls) and scavenging species (corvids and raptors).[95][96]

Elsewhere in Europe the virus killed hundreds (574+) ofDalmatian pelicansin Greece,[97][98]and in Israel around 6000common craneswere found dead at Hula in December 2021.[99]A report by Scientific Task Force on Avian Influenza and Wild Birds on: "H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in poultry and wild birds: Winter of 2021/2022 with focus on mass mortality of wild birds in UK and Israel" summarises the situation up to 24 January 2022 and mentions that "H5N8 HPAI is still responsible for poultry and wild bird cases mainly in Asia, H5N1 has now in effect replaced this subtype in Africa and Eurasia in both poultry and wild birds".[100]

The 2022–2023 season was also the worst recorded outbreak in the United Kingdom, with the British government requiring a so-called "poultry lockdown" which required that farmers keep their birds indoors.[101]Meanwhile, an outbreak of H5N1 on a Spanish mink farm led researchers to believe that they had observed the first case of mammal-to-mammal transmission of H5N1.[102]Human cases were reported in Spain in November 2022, and in the UK in May 2023.[87]

Asia[edit]

By November 2020, large outbreaks of the new strain of H5N1 had started to spread into wild birds and farmed poultry across Asia. In February 2023, human cases were reported in Cambodia.[87]

Africa[edit]

Large losses of poultry and wild birds to H5N1 started to occur in Africa in November 2021 and continued through 2022.[87]

Americas[edit]

Similar to 2021 reports, outbreaks were noted fromgannetcolonies in Canada, with thousands of birds dead in June 2022,[103]as well ascommon eidersandgreat black-backed gulls.[104]Prior to that there were reports of spread in wild birds in over 30 states in the US, including major mortalities in adouble-crested cormorantcolony inBarrington, Illinois,[105][106]the virus also spreading to scavengers including threebald eaglesin Georgia.[107]Mass die-offs of both birds and mammals were noted in Peru during the 2022–2023 season.[108]In particular, the Peruvian government reported the deaths of approximately 63,000 birds as well as 716sea lions,with the WHO noting that mammalian spillovers needed to be "monitored closely".[101][109]In the United States, the 2022–2023 avian outbreak was the worst since H5N1 was first detected.[101]

Ecuadorentered into a three-month "animal-health emergency" on 29 November 2022, just days after its first case was reported, whereasArgentinaandUruguayboth declared "national sanitary emergencies" on 15 February 2023, after their respective first cases were discovered.[110]On 22 May 2023, Brazil, as the world's largest exporter of chicken meat, declared a 180-day emergency following several cases detected in wild birds and created an emergency operations center to plan for and mitigate potential further spread of H5N1.[111]Human cases were reported in Ecuador and Chile.[87]

In March 2024, H5N1 infections were recorded for the first time in deceased and sick livestock located in the United States.Goatsand cows in three states became ill after exposure to wild birds and culled poultry.[112]In early April, H5N1 was reported to have spread amongstdairy cowherds in multiple states of the USA, indicating cow-to-cow spread, possibly occurring while the animals were being milked.[113]A dairy worker in Texas also became infected, withconjunctivitisbeing the main symptom.[114]

On 22 May 2024, a farm worker in Michigan was infected with the H5N1 virus due to their regular exposure to infected dairy cows. The person had mild symptoms and recovered.[115]On 30 May, it was announced that a second Michigan farm worker from a different dairy farm had been diagnosed with H5N1 after exhibiting respiratory symptoms.[116][117]By mid July, seven human cases in the USA were reported in workers at both dairy and poultry farms.[118]

Antarctica[edit]

H5N1 was detected in dead birds on the Antarctic mainland for the first time in February 2024.[119]

Arctic[edit]

In December 2023, conservation officials confirmed that apolar bearhad died of H5N1 near Alaska's northernmost city,Utqiagvik.[120]

Australia[edit]

In May 2024, H5N1 was detected for the first time in Australia after a human child who had returned to the country from India tested positive. The child had a severe infection but recovered.[121]

Mammalian infections[edit]

H5N1 transmission studies in ferrets (2011)[edit]

Novel,contagiousstrains of H5N1 were created by Ron Fouchier of theErasmus Medical Centerin Rotterdam, the Netherlands, who first presented his work to the public at an influenza conference in Malta in September 2011. Three mutations were introduced into the H5N1 virus genome, and the virus was then passed from the noses of infectedferretsto the noses of uninfected ones, which was repeated 10 times.[122]After these 10 passages the H5N1 virus had acquired the ability of transmission between ferrets via aerosols or respiratory droplets.

After Fouchier offered an article describing this work to the leading academic journalScience,the USNational Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity(NSABB) recommended against publication of the full details of the study, and the one submitted to Nature by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin describing related work. However, after additional consultations at the World Health Organization and by the NSABB, the NSABB reversed its position and recommended publication of revised versions of the two papers.[123]However, then theDutch governmentdeclared that this type of manuscripts required Fouchier to apply for an export permit in the light of EU directive 428/2009 on dual use goods.[note 1]After much controversy surrounding the publishing of his research, Fouchier complied (under formal protest) with Dutch government demands to obtain a special permit[124]for submitting his manuscript, and his research appeared in a special issue of the journalSciencedevoted to H5N1.[125][126][127]The papers by Fouchier and Kawaoka conclude that it is entirely possible that a natural chain of mutations could lead to an H5N1 virus acquiring the capability of airborne transmission between mammals, and that a H5N1 influenza pandemic would not be impossible.[128]

In May 2013, it was reported that scientists at theHarbin Veterinary Research InstituteinHarbin,China, had created H5N1 strains which passed betweenguinea pigs.[129]

In response to Fouchier and Kawaoka's work, a number of scientists expressed concerns with therisksof creating novel potential pandemic pathogens, culminating in the formation ofthe Cambridge Working Group,a consensus statement calling for an assessment of the risks and benefits of such research.[130][131]

Mammal-to-mammal transmission (2022–2024)[edit]

Although mammals, including humans, had become infected with H5N1 bird flu strains in the past, these cases had ostensibly been caused by direct exposure to infected birds, such as through consumption of birds by wildlife or exposure to infected poultry by farmers. In contrast, the October 2022 mammalian outbreak of H5N1 on a Spanish mink farm showed evidence of being the first recorded case of mammal-to-mammal transmission, with 4 percent of the farm's mink population dying from H5N1-related haemorrhagic pneumonia.[102][132]The mink respiratory tract is particularly well suited to act as a pathway of viral transmission into humans, which has concerned public health professionals due to the production of all but one approved human vaccine requiring the eggs of chickens, which H5N1 kills at a 90–100 percent fatality rate.[133]Infected mink in Spain were also found to have exhibited the "PB2" viral mutation found when H5N1 jumped into pigs over a decade prior, adding to fears that farms could be acting as incubators and/orreservoirsof the virus, similar to the role of minks inSARS-CoV-2.[102]

As of January 2023, fifteen species of wild and captive mammals had become infected with H5N1 throughout the United States.[134]A massCaspian sealdie-off in December 2022, with 700 infected seals found dead along the Caspian Sea coastline of Russia'sDagestanrepublic,worried researchers regarding the possibility that wild mammal-to-mammal spread had begun.[135]A similar mass die-off of 95% ofsouthern elephant sealpups in 2023 also raised concerns of mammal-to-mammal spread, as nursing pups would have had less exposure to birds.[136]

In April 2024, spread of H5N1 amongst dairy cow herds in nine states of the USA strongly indicated the presence of cow-to-cow transmission possibly occurring while the animals were being milked.[113][137]Although mortality in bovines infected with H5N1 is rare, abundant virus shedding in the milk is evident.[113]Around 50% of cats that lived on the affected dairy farms and were fed unpasteurised milk from symptomatic cows died within a few days from severe systemic influenza infection, raising significant concerns of cross-species mammal-to-mammal transmission.[138]

Society and culture[edit]

H5N1 has had a significant effect onhumansociety,especially thefinancial,political,social,and personal responses to both actual and predicteddeathsinbirds,humans,and otheranimals.Billions of dollars are being raised and spent to research H5N1 and prepare for a potentialavian influenzapandemic.Over $10 billion have been spent and over 200 million birds have been killed to try to contain H5N1.[139][140][141][142][143][144][145][146][147]

People have reacted by buying less chicken, causing poultry sales and prices to fall.[148]Many individuals have stockpiled supplies for a possible flu pandemic. International health officials and other experts have pointed out that many unknown questions still hover around the disease.[149]

Dr.David Nabarro,Chief Avian Flu Coordinator for the United Nations, and former Chief of Crisis Response for the World Health Organization has described himself as "quite scared" about H5N1's potential impact on humans. Nabarro has been accused of being alarmist before, and on his first day in his role for the United Nations, he proclaimed the avian flu could kill 150 million people. In an interview with theInternational Herald Tribune,Nabarro compares avian flu toAIDSin Africa, warning that underestimations led to inappropriate focus for research and intervention.[150]

See also[edit]

- Antigenic shift

- Avian influenza virus

- Favipiravir

- Fu gian flu

- H5N1 clinical trials

- H7N9

- Influenzavirus A

- International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases

- National Influenza Centers

- Swine influenza

- Zoonosis

Notes[edit]

- ^The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) listsstrategic goodswith prohibited goods or goods that require a special permit for import and export without which the carrier faces pecuniary punishment or up to 5 years' imprisonment.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^"Influenza (Avian and other zoonotic)".who.int.World Health Organization.3 October 2023.Retrieved2024-05-06.

- ^abBourk, India (26 April 2024)."'Unprecedented': How bird flu became an animal pandemic ".bbc.BBC.Retrieved2024-05-08.

- ^abc"Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People | Avian Influenza (Flu)".cdc.gov.US:Centers for Disease Control.2024-04-19.Retrieved2024-05-08.

- ^"Bird flu (avian influenza)".betterhealth.vic.gov.au.Victoria, Australia: Department of Health & Human Services.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^ab"Avian influenza: guidance, data and analysis".gov.uk.2021-11-18.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^ab"Avian Influenza in Birds".cdc.gov.US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022-06-14.Retrieved2024-05-06.

- ^"Bird flu (avian influenza): how to spot and report it in poultry or other captive birds".gov.uk.UK: Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs and Animal and Plant Health Agency. 2022-12-13.Retrieved2024-05-06.

- ^"Influenza Type A Viruses".cdc.gov.US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024-02-01.Retrieved2024-05-03.

- ^Devlin, Hannah (2024-04-18)."Risk of bird flu spreading to humans is 'enormous concern', says WHO".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved2024-05-06.

- ^"Avian influenza A(H5N1): For health professionals".canada.ca.2023-02-20.Retrieved2024-05-22.

- ^"Emergence and Evolution of H5N1 Bird Flu | Avian Influenza (Flu)".cdc.gov.US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023-06-06.Retrieved2024-05-03.

- ^Huang, Pan; Sun, Lujia; Li, Jinhao; et al. (2023-06-16)."Potential cross-species transmission of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 subtype (HPAI H5) viruses to humans calls for the development of H5-specific and universal influenza vaccines".Cell Discovery.9(1): 58.doi:10.1038/s41421-023-00571-x.ISSN2056-5968.PMC10275984.PMID37328456.

- ^"Highlights in the History of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) Timeline – 2020-2024 | Avian Influenza (Flu)".cdc.gov.US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024-04-22.Retrieved2024-05-08.

- ^Caliendo, V.; Lewis, N. S.; Pohlmann, A.; et al. (2022-07-11)."Transatlantic spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 by wild birds from Europe to North America in 2021".Scientific Reports.12(1): 11729.Bibcode:2022NatSR..1211729C.doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13447-z.ISSN2045-2322.PMC9276711.PMID35821511.

- ^"Bird flu is bad for poultry and cattle. Why it's not a dire threat for most of us — yet".NBC News. 2024-05-02.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^McKie, Robin (2024-04-20)."Next pandemic likely to be caused by flu virus, scientists warn".The Observer.ISSN0029-7712.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^"Vaccination of poultry against highly pathogenic avian influenza – Available vaccines and vaccination strategies".efsa.europa.eu.2023-10-10.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^"Two possible bird flu vaccines could be available within weeks, if needed".NBC News. 2024-05-01.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^"Avian influenza (bird flu) | European Medicines Agency".ema.europa.eu.Retrieved2024-05-09.

- ^"Bird flu (avian influenza): how to spot and report it in poultry or other captive birds".Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs and Animal and Plant Health Agency.2022-12-13.Retrieved2024-05-06.

- ^"Avian flu".The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB).Retrieved2024-06-25.

- ^CDC (2024-05-30)."Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Retrieved2024-06-11.

- ^"Questions and Answers on Avian Influenza".An official website of the European Commission.11 June 2024.Retrieved2024-06-11.

- ^"Reported Human Infections with Avian Influenza A Viruses | Avian Influenza (Flu)".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.2024-02-01.Retrieved2024-06-11.

- ^"Zoonotic influenza".Wordl Health Organization.Retrieved2024-06-16.

- ^"The next pandemic: H5N1 and H7N9 influenza?".Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.Retrieved2024-06-16.

- ^"Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus in Animals: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations".Centers for Disease Control.2024-06-05.Retrieved2024-06-13.

- ^Bertram S, Glowacka I, Steffen I, et al. (September 2010)."Novel insights into proteolytic cleavage of influenza virus hemagglutinin".Reviews in Medical Virology.20(5): 298–310.doi:10.1002/rmv.657.PMC7169116.PMID20629046.

The influenza virus HA binds to Alpha 2–3 linked (avian viruses) or Alpha 2–6 linked (human viruses) sialic acids presented by proteins or lipids on the host cell surface.

- ^abShinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, et al. (March 2006). "Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway".Nature.440(7083): 435–436.Bibcode:2006Natur.440..435S.doi:10.1038/440435a.PMID16554799.S2CID9472264.

- ^abvan Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T (2006). "H5N1 Virus Attachment to Lower Respiratory Tract".Science.312(5772): 399.doi:10.1126/science.1125548.PMID16556800.S2CID33294327.

- ^Bennett, Nicholas John (13 October 2021)."Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology".Medscape Reference.Retrieved28 April2024.

Avian influenza is still primarily a respiratory infection but involves more of the lower airways than human influenza typically does. This is likely due to differences in the hemagglutinin protein and the types of sialic acid residues to which the protein binds. Avian viruses tend to prefer sialic acid Alpha (2-3) galactose, which, in humans, is found in the terminal bronchi and alveoli. Conversely, human viruses prefer sialic acid Alpha (2-6) galactose, which is found on epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract.

- ^"Avian influenza A(H5N1) virus".who.int.Retrieved2024-05-28.

- ^Li FC, Choi BC, Sly T, Pak AW (June 2008)."Finding the real case-fatality rate of H5N1 avian influenza".J Epidemiol Community Health.62(6): 555–9.doi:10.1136/jech.2007.064030.PMID18477756.S2CID34200426.

- ^"A revision of the system of nomenclature for influenza viruses: a WHO Memorandum".Bull World Health Organ.58(4): 585–591. 1980.PMC2395936.PMID6969132.

This Memorandum was drafted by the signatories listed on page 590 on the occasion of a meeting held in Geneva in February 1980.

- ^Payungporn S, Chutinimitkul S, Chaisingh A, Damrongwantanapokin S, Nuansrichay B, Pinyochon W, Amonsin A, Donis RO, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan T (2006)."Discrimination between Highly Pathogenic and Low Pathogenic H5 Avian Influenza A Viruses".Emerging Infectious Diseases.12(4): 700–701.doi:10.3201/eid1204.051427.PMC3294708.PMID16715581.

- ^"Influenza A Subtypes and the Species Affected | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.2024-05-13.Retrieved2024-06-17.

- ^CDC (2024-02-01)."Influenza Type A Viruses".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Retrieved2024-05-03.

- ^CDC (2023-03-30)."Types of Influenza Viruses".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Retrieved2024-06-17.

- ^CDC (2024-06-11)."Avian Influenza Type A Viruses".Avian Influenza (Bird Flu).Retrieved2024-06-17.

- ^Márquez Domínguez L, Márquez Matla K, Reyes Leyva J, Vallejo Ruíz V, Santos López G (December 2023)."Antiviral resistance in influenza viruses".Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France).69(13): 16–23.doi:10.14715/cmb/2023.69.13.3.PMID38158694.

- ^abcKou Z, Lei FM, Yu J, Fan ZJ, Yin ZH, Jia CX, Xiong KJ, Sun YH, Zhang XW, Wu XM, Gao XB, Li TX (2005)."New Genotype of Avian Influenza H5N1 Viruses Isolated from Tree Sparrows in China".J. Virol.79(24): 15460–15466.doi:10.1128/JVI.79.24.15460-15466.2005.PMC1316012.PMID16306617.

- ^abcThe World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network. (2005)."Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia".Emerging Infectious Diseases.11(10): 1515–1521.doi:10.3201/eid1110.050644.PMC3366754.PMID16318689.

Figure 1 shows a diagramatic representation of the genetic relatedness of Asian H5N1hemagglutiningenes from various isolates of the virus - ^Shao, Wenhan; Li, Xinxin; Goraya, Mohsan Ullah; Wang, Song; Chen, Ji-Long (2017-08-07)."Evolution of Influenza A Virus by Mutation and Re-Assortment".International Journal of Molecular Sciences.18(8): 1650.doi:10.3390/ijms18081650.ISSN1422-0067.PMC5578040.PMID28783091.

- ^Eisfeld AJ, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y (January 2015)."At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins".Nature Reviews. Microbiology.13(1): 28–41.doi:10.1038/nrmicro3367.PMC5619696.PMID25417656.

- ^Schultz J (2005-11-28)."Bird flu vaccine won't precede pandemic".United Press International. Archived fromthe originalon February 15, 2006.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Enserick, M. (2005-08-12)."Avian Influenza:'Pandemic Vaccine' Appears to Protect Only at High Doses".American Scientist.91(2): 122.doi:10.1511/2003.2.122.Archivedfrom the original on 2006-02-28.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Walker K (2006-01-27)."Two H5N1 human vaccine trials to begin".Science Daily. Archived fromthe originalon 2006-02-14.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Gao W, Soloff AC, Lu X, Montecalvo A, Nguyen DC, Matsuoka Y, Robbins PD, Swayne DE, Donis RO, Katz JM, Barratt-Boyes SM, Gambotto A (2006)."Protection of Mice and Poultry from Lethal H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus through Adenovirus-Based Immunization".J. Virol.80(4): 1959–1964.doi:10.1128/JVI.80.4.1959-1964.2006.PMC1367171.PMID16439551.

- ^ab United States Agency for International Development(2006)."Avian Influenza Response: Key Actions to Date".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-04-17.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^ United States Department of Health and Human Services(2002)."Pandemicflu.gov Monitoring outbreaks".Archivedfrom the original on 2006-04-26.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Medline Plus (2006-01-12)."Oseltamivir (Systemic)".National Institutes of Health(NIH). Archived fromthe originalon 2006-04-25.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Associated Press,"Tamiflu is Set Aside for WHO,"The Wall Street Journal,April 20, 2006, p. D6.

- ^Integrated Regional Information Networks(2006-04-02)."Middle East: Interview with WHO experts Hassan al-Bushra and John Jabbour".Alertnet Reuters foundation. Archived fromthe originalon 2006-04-07.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Bernd Sebastian Kamps; Christian Hoffmann."Zanamivir".Influenza Report.Archivedfrom the original on 2006-10-27.Retrieved2006-10-15.

- ^Zheng B.-J. (June 10, 2008)."Delayed antiviral plus immunomodulator treatment still reduces mortality in mice infected by high inoculum of influenza A/H5N1 virus".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.105(23): 8091–8096.Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8091Z.doi:10.1073/pnas.0711942105.PMC2430364.PMID18523003.

- ^"Oseltamivir-resistant H5N1 virus isolated from Vietnamese girl".Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). October 14, 2005.Archivedfrom the original on September 25, 2006.Retrieved2006-10-15.

- ^"U.N. Says Bird Flu Awareness Increases".National Public Radio(NPR). October 12, 2006.Retrieved2006-10-15.[dead link]

- ^ Collins PJ, Haire LF, Lin YP, Liu J, Russell RJ, Walker PA, Skehel JJ, Martin SR, Hay AJ, Gamblin SJ (2008)."Crystal structures of oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus neuraminidase mutants".Nature.453(7199): 1258–1261.Bibcode:2008Natur.453.1258C.doi:10.1038/nature06956.PMID18480754.S2CID4383625.

- ^ Garcia-Sosa AT, Sild S, Maran U (2008). "Design of Multi-Binding-Site Inhibitors, Ligand Efficiency, and Consensus Screening of Avian Influenza H5N1 Wild-Type Neuraminidase and of the Oseltamivir-Resistant H274Y Variant".J. Chem. Inf. Model.48(10): 2074–2080.doi:10.1021/ci800242z.PMID18847186.

- ^Charostad, Javad; Rezaei Zadeh Rukerd, Mohammad; Mahmoudvand, Shahab; Bashash, Davood; Hashemi, Seyed Mohammad Ali; Nakhaie, Mohsen; Zandi, Keivan (September 2023)."A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: An imminent threat at doorstep".Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease.55:102638.doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2023.102638.ISSN1477-8939.

- ^CDC (2024-06-10)."1880-1959 Highlights in the History of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) Timeline".Avian Influenza (Bird Flu).Retrieved2024-07-08.

- ^CDC (2024-06-10)."1960-1999 Highlights in the History of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) Timeline".Avian Influenza (Bird Flu).Retrieved2024-07-08.

- ^Chan, Paul K. S. (2002-05-01)."Outbreak of Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection in Hong Kong in 1997".Clinical Infectious Diseases.34(Supplement_2): S58–S64.doi:10.1086/338820.ISSN1537-6591.

- ^Bourk, India (26 April 2024)."'Unprecedented': How bird flu became an animal pandemic ".bbc.Retrieved2024-05-08.

- ^CDC (2024-07-05)."H5N1 Bird Flu: Current Situation".Avian Influenza (Bird Flu).Retrieved2024-07-08.

- ^ "Studies Spot Obstacle to Human Transmission of Bird Flu".Forbes.2006-03-22. Archived fromthe originalon May 23, 2006.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^ Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (2005)."Wild birds and Avian Influenza".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-11-01.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^ Brstilo M. (2006-01-19)."Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Croatia Follow-up report No. 4".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-05-14.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority(2006-04-04)."Scientific Statement on Migratory birds and their possible role in the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2006-05-07.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^"Bird flu may be spread indirectly, WHO says".Reuters.Reuters. 2008-01-17.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-12-01.Retrieved2009-09-01.

- ^Sturm-Ramirez KM, Ellis T, Bousfield B, Bissett L, Dyrting K, Rehg JE, Poon L, Guan Y, Peiris M, Webster RG (2004)."Reemerging H5N1 Influenza Viruses in Hong Kong in 2002 Are Highly Pathogenic to Ducks".J. Virol.78(9): 4892–45901.doi:10.1128/JVI.78.9.4892-4901.2004.PMC387679.PMID15078970.

- ^Li KS, Guan Y, Wang J, Smith GJ, Xu KM, Duan L, Rahardjo AP, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen TD, Estoepangestie AT, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Long HT, Hanh NT, Webby RJ, Poon LL, Chen H, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Webster RG, Peiris JS (2004). "Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in eastern Asia".Nature.430(6996): 209–213.Bibcode:2004Natur.430..209L.doi:10.1038/nature02746.PMID15241415.S2CID4410379.

This was reprinted in 2005:Li KS, Guan Y, Wang J, Smith GJ, Xu KM, Duan L, Rahardjo AP, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen TD, Estoepangestie AT, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Long HT, Hanh NT, Webby RJ, Poon LL, Chen H, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Webster RG, Peiris JS (2005)."Today's Pandemic Threat: Genesis of a Highly Pathogenic and Potentially Pandemic H5N1 Influenza Virus in Eastern Asia".In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.).The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005).Washington DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 116–130. Archived fromthe originalon 2006-09-14. - ^World Health Organization(2005-10-28)."H5N1 avian influenza: timeline"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-27.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Chen H, Deng G, Li Z, Tian G, Li Y, Jiao P, Zhang L, Liu Z, Webster RG, Yu K (2004)."The evolution of H5N1 influenza viruses in ducks in southern China".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.101(28): 10452–10457.Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110452C.doi:10.1073/pnas.0403212101.PMC478602.PMID15235128.

- ^Sanjuán R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R (October 2010)."Viral mutation rates".Journal of Virology.84(19): 9733–48.doi:10.1128/JVI.00694-10.PMC2937809.PMID20660197.

- ^Kou Z, Lei FM, Yu J, Fan ZJ, Yin ZH, Jia CX, Xiong KJ, Sun YH, Zhang XW, Wu XM, Gao XB, Li TX (2005)."New Genotype of Avian Influenza H5N1 Viruses Isolated from Tree Sparrows in China".J. Virol.79(24): 15460–15466.doi:10.1128/JVI.79.24.15460-15466.2005.PMC1316012.PMID16306617.

- ^The World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network. (2005)."Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia".Emerging Infectious Diseases.11(10): 1515–1521.doi:10.3201/eid1110.050644.PMC3366754.PMID16318689.Figure 1 shows a diagramatic representation of the genetic relatedness of Asian H5N1hemagglutiningenes from various isolates of the virus

- ^CDC (2024-05-15)."Transmission of Bird Flu Viruses Between Animals and People".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Retrieved2024-06-10.

- ^"Global AIV with Zoonotic Potential".The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.29 July 2020.Retrieved2024-06-24.

- ^Plaza, Pablo I.; Gamarra-Toledo, Víctor; Euguí, Juan Rodríguez; Lambertucci, Sergio A. (2024)."Recent Changes in Patterns of Mammal Infection with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Worldwide".Emerging Infections Diseases.30(3): 444–452.doi:10.3201/eid3003.231098.PMC10902543.PMID38407173.

- ^Lee, Kelley; Fang, Jennifer (2013).Historical Dictionary of the World Health Organization.Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN9780810878587.

- ^"70 years of GISRS – the Global Influenza Surveillance & Response System".World Health Organization.19 September 2022.Retrieved2024-06-13.

- ^Beigel JH; Farrar J; Han AM; Hayden FG; Hyer R; de Jong MD; Lochindarat S; Nguyen TK; Nguyen TH; Tran TH; Nicoll A; Touch S; Yuen KY (2005). "Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans; Writing Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) Consultation on Human Influenza A/H5".N. Engl. J. Med.353(13): 1374–1385.CiteSeerX10.1.1.730.7890.doi:10.1056/NEJMra052211.PMID16192482.

- ^Rosenthal E (2006-04-15)."Bird Flu Virus May Be Spread by Smuggling".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2013-05-20.Retrieved2006-04-18.

- ^Gu, Jiang; Xie, Zhigang; Gao, Zhancheng; Liu, Jinhua; Korteweg, Christine; Ye, Juxiang; Lau, Lok Ting; Lu, Jie; Gao, Zifen; Zhang, Bo; McNutt, Michael A. (2007-09-29)."H5N1 infection of the respiratory tract and beyond: a molecular pathology study".The Lancet.370(9593): 1137–1145.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61515-3.ISSN0140-6736.PMC7159293.PMID17905166.

- ^"North Korea confirms bird flu outbreak at duck farm".Yonhap News. 2013-05-20.Archivedfrom the original on 2014-04-07.

- ^abcde"Avian Influenza Situation Reports".woah.org.World Organisation for Animal Health.Retrieved26 March2024.

- ^Miller, Brittney J. (2022)."Why unprecedented bird flu outbreaks sweeping the world are concerning scientists".Nature.606(7912): 18–19.Bibcode:2022Natur.606...18M.doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01338-2.PMID35618804.S2CID249096351.

- ^"Urgent action needed to address impacts of Avian Influenza. Outbreak of bird disease is worst on record".

- ^"Wilde vogels bezwijken aan vogelgriep: 'Blijf uit de buurt van dode dieren'".7 June 2022.

- ^ab"Hundreds of seabirds being lost to avian flu in Shetland".BBC News.6 June 2022.

- ^"Bird Flu Update June 2022 – Bird flu updates – Our work – the RSPB Community".June 2022.

- ^@StKildaNTS (8 June 2022)."We completed the Great Skua census today on #StKilda and the impact of the current #AvianInfluenza outbreak is clea..."(Tweet) – viaTwitter.

- ^"Avian flu kills birds at St Kilda World Heritage Site".BBC News.7 June 2022.

- ^"Huge concern for Scotland's seabirds as number dying from Avian Influenza continues to increase".

- ^"Dozens of dead birds in suspected flu outbreak at Highlands reserve".BBC News.13 May 2022.

- ^"Mass mortality of Dalmatian pelicans observed in Greece due to Avian influenza".11 March 2022.

- ^"Bird flu hits world's largest Dalmatian Pelican colony".16 March 2022.

- ^"Israel and UK facing record-breaking bird flu outbreaks".10 January 2022.

- ^"H5N1 HIGHLY PATHOGENIC AVIAN INFLUENZA IN POULTRY AND WILD BIRDS: WINTER OF 2021/2022 WITH FOCUS ON MASS MORTALITY OF WILD BIRDS IN UK AND ISRAEL"(PDF).cms.int.2022-01-24.Retrieved2023-03-02.

- ^abcPrater, Erin (8 February 2023)."The spillover of bird flu to mammals must be 'monitored closely,' WHO officials warn: 'We need to be ready to face outbreaks in humans'".Fortune. Archived fromthe originalon 9 February 2023.Retrieved9 February2023.

- ^abcNuki, Paul (2 February 2023)."How worried should we be about avian flu?".The Telegraph. Archived fromthe originalon 2 February 2023.Retrieved5 February2023.

- ^"Hundreds of birds dead or dying of avian flu land on Cape Breton shores".Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.2022-06-06.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-06-06.Retrieved2023-03-02.

- ^"Mortalities in colonial seabirds associated with a highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus in Quebec".31 May 2022.

- ^"Hundreds of Birds Found Dead of Bird Flu at Suburban Lake, Experts Fear Bigger Outbreak".14 April 2022.

- ^"Bald eagles dying, egg prices rising: Bird flu spreads to more than 30 states".NBC News.16 April 2022.

- ^"Avian Influenza Detected in Bald Eagles in Georgia | Department of Natural Resources Division".

- ^"Sernanp despliega protocolo de monitoreo ante casos de aves y lobos marinos afectados por influenza aviar en áreas naturales protegidas"(in Spanish). National Service of Protected Areas by the State (SERNANP). 6 February 2023. Archived fromthe originalon 7 February 2023.Retrieved10 February2023.

- ^"Bird flu kills sea lions and thousands of pelicans in Peru's protected areas".Reuters. 21 February 2023. Archived fromthe originalon 21 February 2023.Retrieved21 February2023.

- ^Polansek, Tom (15 February 2023)."Bird flu spreads to new countries, threatens non-stop 'war' on poultry".Reuters. Archived fromthe originalon 16 February 2023.Retrieved17 February2023.

- ^Mano, Ana (22 May 2023)."Brazil declares 180-day animal health emergency amid avian flu cases in wild birds".Reuters. Archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2023.Retrieved23 May2023.

- ^Schnirring, Lisa (25 March 2024)."Sick cows in 2 states test positive for avian flu".University of Minnesota. CIDRAP.Retrieved26 March2024.

- ^abcKozlov, Max (2024-06-05)."Huge amounts of bird-flu virus found in raw milk of infected cows".Nature.doi:10.1038/d41586-024-01624-1.ISSN0028-0836.PMID38840011.

- ^Schnirring, Lisa (1 April 2024)."Avian flu infects person exposed to sick cows in Texas".University of Minnesota. CIDRAP.Retrieved2 April2024.

- ^Edwards, Erika; Miller, Sara G. (2024-05-22)."Second human case of bird flu linked to dairy cows found in Michigan".NBC News.

- ^Mandavilli, Apoorva (May 30, 2024)."Bird Flu Has Infected a Third U.S. Farmworker".The New York Times.RetrievedMay 31,2024.

- ^Edwards, Erika (May 30, 2024)."Third person infected in U.S. bird flu outbreak".NBC News.RetrievedMay 31,2024.

- ^Steenhuysen, Julie (13 July 2024)."Colorado reports three presumptive human bird flu cases, CDC says".Reuters.Retrieved13 July2024.

- ^Weston, Phoebe (27 February 2024)."Scientists confirm first cases of bird flu on mainland Antarctica".The Guardian.Retrieved21 March2024.

- ^Weston, Phoebe (2 January 2024)."Polar bear dies from bird flu as H5N1 spreads across globe".The Guardian.Archived fromthe originalon 4 January 2024.Retrieved4 January2024.

- ^"First human H5N1 case reported in Australia as another highly pathogenic strain of bird flu detected on Victorian farm".The Guardian Australia. 22 May 2024.Retrieved22 May2024.

- ^ Harmon, Katherine (2011-09-19)."What Will the Next Influenza Pandemic Look Like?".Scientific American.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-03-02.Retrieved2012-01-23.

- ^David Malakoff (March 30, 2012)."Breaking News: NSABB Reverses Position on Flu Papers".Science Insider.Archived fromthe originalon June 30, 2012.RetrievedJune 23,2012.

- ^Nell Greenfieldboyce (April 24, 2012)."Bird Flu Scientist has Applied for Permit to Export Research".NPR.Archivedfrom the original on June 22, 2012.RetrievedJune 23,2012.

- ^Nell Greenfieldboyce (June 21, 2012)."Journal Publishes Details on Contagious Bird Flu Created in Lab".National Public Radio (NPR).Archivedfrom the original on June 22, 2012.RetrievedJune 23,2012.

- ^"H5N1"(Special Issue).Science.June 21, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on June 25, 2012.RetrievedJune 23,2012.

- ^Herfst, S.; Schrauwen, E. J. A.; Linster, M.; Chutinimitkul, S.; De Wit, E.; Munster, V. J.; Sorrell, E. M.; Bestebroer, T. M.; Burke, D. F.; Smith, D. J.; Rimmelzwaan, G. F.; Osterhaus, A. D. M. E.; Fouchier, R. A. M. (2012)."Airborne Transmission of Influenza A/H5N1 Virus Between Ferrets".Science.336(6088): 1534–1541.Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1534H.doi:10.1126/science.1213362.PMC4810786.PMID22723413.

- ^Brown, Eryn (June 21, 2012)."Scientists create bird flu that spreads easily among mammals".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on June 23, 2012.RetrievedJune 23,2012.

- ^Keim, Brandon (2013-05-02)."Chinese Scientists Create New Mutant Bird-Flu Virus".Wired.ISSN1059-1028.Retrieved2023-02-07.

- ^"Scientists Resume Efforts to Create Deadly Flu Virus, with US Government's Blessing".Forbes.

- ^"From anthrax to bird flu – the dangers of lax security in disease-control labs".TheGuardian.18 July 2014.

- ^Pelley, Lauren (2 February 2023)."Bird flu keeps spreading beyond birds. Scientists worry it signals a growing threat to humans, too".CBC News. Archived fromthe originalon 2 February 2023.Retrieved5 February2023.

- ^Tufekci, Zeynep (3 February 2023)."An Even Deadlier Pandemic Could Soon Be Here".New York Times.Archived fromthe originalon 5 February 2023.Retrieved5 February2023.

- ^"2022-2023 Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Mammals".Avian Influenza.USDA APHIS. Archived fromthe originalon 30 January 2023.Retrieved5 February2023.

- ^Merrick, Jane (1 February 2023)."Mass death of seals raises fears bird flu is jumping between mammals, threatening new pandemic".The i newspaper. Archived fromthe originalon 3 February 2023.Retrieved15 February2023.

- ^Kwan, Jacklin (22 January 2024)."Bird flu wipes out over 95% of southern elephant seal pups in 'catastrophic' mass death".livescience.Retrieved23 January2024.

- ^Mallapaty, Smriti (2024-04-27)."Bird flu virus has been spreading in US cows for months, RNA reveals".Nature.doi:10.1038/d41586-024-01256-5.PMID38678111.

- ^Burrough, Eric; Magstadt, Drew; Main, Rodger (29 April 2024)."Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024".Emerging Infectious Diseases.30(7): 1335–1343.doi:10.3201/eid3007.240508.PMC11210653.PMID38683888.Retrieved30 April2024.

- ^Rosenthal E, Bradsher K (2006-03-16)."Is Business Ready for a Flu Pandemic?".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2013-05-02.Retrieved2012-01-23.

- ^State.govArchived2006-09-14 at theWayback Machine

- ^NewswireArchivedMay 17, 2008, at theWayback Machine

- ^US AIDArchived2008-08-15 at theWayback Machine

- ^"BMO Financial Group"..bmo.Archivedfrom the original on 2009-05-03.Retrieved2010-04-05.

- ^"Council on Foreign Relations".Cfr.org. Archived fromthe originalon 2008-10-13.Retrieved2010-04-05.

- ^Reuters[dead link]articleVietnam to unveil advanced plan to fight bird flupublished on April 28, 2006

- ^Poultry sector suffers despite absence of bird fluArchivedMarch 30, 2006, at theWayback Machine

- ^Barber, Tony (2006-02-13)."Italy imposes controls after bird flu discovery".FT.Retrieved2012-08-19.

- ^India eNews[usurped]articlePakistani poultry industry demands 10-year tax holidaypublished May 7, 2006 says "Pakistani poultry farmers have sought a 10-year tax exemption to support their dwindling business after the detection of the H5N1 strain of bird flu triggered a fall in demand and prices, a poultry trader said."

- ^International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)Archived2006-04-27 at theWayback MachineScientific Seminar on Avian Influenza, the Environment and Migratory Birds on 10–11 April 2006published 14 April 2006.

- ^McNeil, Donald G. Jr.(March 28, 2006)."The response to bird flu: Too much or not enough? UN expert stands by his dire warnings".International Herald Tribune.Archivedfrom the original on February 20, 2008.

Sources[edit]

- Analysis of the efficacy of an adjuvant-based inactivated pandemic H5N1 influenza virus vaccine.https://link.springer /article/10.1007%2Fs00705-019-04147-7Ainur NurpeisovaEmail authorMarkhabat KassenovNurkuisa RametovKaissar TabynovGourapura J. RenukaradhyaYevgeniy VolginAltynay SagymbayAmanzhol MakbuzAbylay SansyzbayBerik Khairullin

Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems (RIBSP), Zhambyl Region, Republic of Kazakhstan

External links[edit]

- Influenza Research Database– Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- WHOWorld Health Organization

- WHO's Avian Flu Facts Sheet for 2006

- Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and ResponseGuide to WHO's H5N1 pages

- Avian Influenza Resources (updated)– tracks human cases and deaths

- National Influenza Pandemic Plans

- WHO Collaborating Centres and Reference LaboratoriesCenters, names, locations, and phone numbers

- FAO Avian Influenza portalArchived2012-01-26 at theWayback MachineInformation resources, animations, videos, photos

- FAOFood and Agriculture Organisation – Bi-weekly Avian Influenza Maps – tracks animal cases and deaths

- FAO Bird Flu disease card

- FAO Socio-Economic impact of AIProjects, Information resources

- OIEWorld Organisation for Animal Health– tracks animal cases and deaths

- Official outbreak reports by countryArchived2012-12-13 at theWayback Machine

- Official outbreak reports by week

- Chart of outbreaks by countryArchived2012-04-19 at theWayback Machine

- Health-EU PortalEU response to Avian Influenza.

- Avian influenza – Q & A'sfactsheet fromEuropean Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- United Kingdom

- Exotic Animal Disease Generic Contingency Plan–DEFRAgeneric contingency plan for controlling and eradicating an outbreak of an exotic animal disease.PDFhosted byBBC.

- UK Influenza Pandemic Contingency Planby theNational Health Service– a government entity.PDFhosted byBBC

- UK Department of HealthArchived2009-07-09 at theWayback Machine

- United States

- Center for Infectious Disease Research and PolicyArchived2013-06-17 at theWayback MachineAvian Influenza (Bird Flu): Implications for Human Disease – An overview of Avian Influenza

- PandemicFlu.GovU.S. Government's avian flu information site

- USAIDU.S. Agency for International Development – Avian Influenza Response

- CDC,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention– responsible agency for avian influenza in humans in US – Facts About Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) and Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus

- USGS – NWHCNational Wildlife Health Center – responsible agency for avian influenza in animals in US

- Wildlife Disease Information NodeA part of the National Biological Information Infrastructure and partner of the NWHC, this agency collects and distributes news and information about wildlife diseases such as avian influenza and coordinates collaborative information sharing efforts.

- HHSU.S.Department of Health & Human Services's Pandemic Influenza Plan