Halothane

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Fluothane |

| AHFS/Drugs | FDA Professional Drug Information |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | Inhalation |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokineticdata | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic(CYP2E1[4]) |

| Excretion | Kidney,respiratory |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChemCID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard(EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.270 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

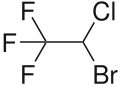

| Formula | C2HBrClF3 |

| Molar mass | 197.38g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.871 g/cm3(at 20 °C) |

| Melting point | −118 °C (−180 °F) |

| Boiling point | 50.2 °C (122.4 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Halothane,sold under the brand nameFluothaneamong others, is ageneral anaesthetic.[5]It can be used to induce or maintainanaesthesia.[5]One of its benefits is that it does not increase the production ofsaliva,which can be particularly useful in those who are difficult tointubate.[5]It is given byinhalation.[5]

Side effects include anirregular heartbeat,respiratory depression,andhepatotoxicity.[5]Like all volatile anesthetics, it should not be used in people with a personal or family history ofmalignant hyperthermia.[5]It appears to be safe inporphyria.[6]It is unclear whether its usage duringpregnancyis harmful to the fetus, and its use during aC-sectionis generally discouraged.[7]Halothane is achiralmolecule that is used as aracemic mixture.[8]

Halothane was discovered in 1951.[9]It was approved for medical use in the United States in 1958.[3]It is on theWorld Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10]Its use indeveloped countrieshas been mostly replaced by newer anesthetic agents such assevoflurane.[11]It is no longer commercially available in the United States.[7]Halothane also contributes toozone depletion.[12][13]

Medical uses[edit]

It is a potent anesthetic with aminimum alveolar concentration(MAC) of 0.74%.[14]Itsblood/gas partition coefficientof 2.4 makes it an agent with moderate induction and recovery time.[15]It is not a goodanalgesicand its muscle relaxation effect is moderate.[16]

Halothane is colour-coded red onanaesthetic vaporisers.[17]

Side effects[edit]

Side effects includeirregular heartbeat,respiratory depression,andhepatotoxicity.[5]It appears to be safe inporphyria.[6]It is unclear whether use duringpregnancyis harmful to the baby, and it is not generally recommended for use during aC-section.[7] In rare cases, repeated exposure to halothane in adults was noted to result in severeliverinjury. This occurred in about one in 10,000 exposures. The resulting syndrome was referred to as halothanehepatitis,immunoallergic in origin,[18]and is thought to result from the metabolism of halothane totrifluoroacetic acidvia oxidative reactions in the liver. About 20% of inhaled halothane is metabolized by the liver and these products are excreted in the urine. The hepatitis syndrome had a mortality rate of 30% to 70%.[19]Concern for hepatitis resulted in a dramatic reduction in the use of halothane for adults and it was replaced in the 1980s byenfluraneandisoflurane.[20][21]By 2005, the most common volatile anesthetics used wereisoflurane,sevoflurane,anddesflurane.Since the risk of halothane hepatitis in children was substantially lower than in adults, halothane continued to be used in pediatrics in the 1990s as it was especially useful for inhalation induction of anesthesia.[22][23]However, by 2000, sevoflurane, excellent for inhalation induction, had largely replaced the use of halothane in children.[24]

Halothane sensitises the heart to catecholamines, so it is liable to cause cardiac arrhythmia, occasionally fatal, particularly ifhypercapniahas been allowed to develop. This seems to be especially problematic in dental anesthesia.[25]

Like all the potent inhalational anaesthetic agents, it is a potent trigger formalignant hyperthermia.[5]Similarly, in common with the other potent inhalational agents, it relaxes uterine smooth muscle and this may increase blood loss during delivery or termination of pregnancy.[26]

Occupational safety[edit]

People can be exposed to halothane in the workplace by breathing it in as waste anaesthetic gas, skin contact, eye contact, or swallowing it.[27]TheNational Institute for Occupational Safety and Health(NIOSH) has set arecommended exposure limit(REL) of 2 ppm (16.2 mg/m3) over 60 minutes.[28]

Pharmacology[edit]

The exact mechanism of the action of general anaestheticshas not been delineated.[29]Halothane activatesGABAAandglycine receptors.[30][31]It also acts as anNMDA receptor antagonist,[31]inhibitsnAChandvoltage-gated sodium channels,[30][32]and activates5-HT3andtwin-pore K+channels.[30][33]It does not affect theAMPAorkainate receptors.[31]

Chemical and physical properties[edit]

Halothane (2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane) is a dense, highly volatile, clear, colourless, nonflammable liquid with a chloroform-like sweet odour. It is very slightly soluble in water and miscible with various organic solvents. Halothane can decompose tohydrogen fluoride,hydrogen chlorideandhydrogen bromidein the presence of light and heat.[34]

| Boiling point: | 50.2 °C | (at 101.325 kPa) |

| Density: | 1.871 g/cm3 | (at 20 °C) |

| Molecular Weight: | 197.4u | |

| Vapor pressure: | 244 mmHg (32kPa) | (at 20 °C) |

| 288 mmHg (38kPa) | (at 24 °C) | |

| MAC: | 0.75 | vol % |

| Blood:gas partition coefficient: | 2.3 | |

| Oil:gas partition coefficient: | 224 |

Chemically, halothane is analkyl halide(not anetherlike many other anesthetics).[4]The structure has one stereocenter, so (R)- and (S)-optical isomersoccur.[citation needed]

Synthesis[edit]

The commercial synthesis of halothane starts fromtrichloroethylene,which is reacted withhydrogen fluoridein the presence ofantimony trichlorideat 130 °C to form2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane.This is then reacted withbromineat 450 °C to produce halothane.[35]

Related substances[edit]

Attempts to find anesthetics with less metabolism led tohalogenated etherssuch asenfluraneandisoflurane.The incidence ofhepaticreactions with these agents is lower. The exact degree ofhepatotoxicpotential of enflurane is debated, although it is minimally metabolized. Isoflurane is essentially not metabolized and reports of associated liver injury are quite rare.[36]Small amounts oftrifluoroacetic acidcan be formed from both halothane and isoflurane metabolism and possibly accounts for cross sensitization of patients between these agents.[37][38]

The main advantage of the more modern agents is lower blood solubility, resulting in faster induction of and recovery from anaesthesia.[39]

History[edit]

Halothane was first synthesized byC. W. SucklingofImperial Chemical Industriesin 1951 at the ICIWidnes Laboratoryand was first used clinically by M. Johnstone inManchesterin 1956. Initially, many pharmacologists and anaesthesiologists had doubts about the safety and efficacy of the new drug. But halothane, which required specialist knowledge and technologies for safe administration, also afforded British anaesthesiologists the opportunity to remake their speciality as a profession during a period, when the newly establishedNational Health Serviceneeded more specialist consultants.[40]In this context, halothane eventually became popular as a nonflammable general anesthetic replacing othervolatile anestheticssuch astrichloroethylene,diethyl etherandcyclopropane.In many parts of the world it has been largely replaced by newer agents since the 1980s but is still widely used in developing countries because of its lower cost.[41]

Halothane was given to many millions of people worldwide from its introduction in 1956 through the 1980s.[42]Its properties include cardiac depression at high levels, cardiac sensitization tocatecholaminessuch asnorepinephrine,and potent bronchial relaxation. Its lack of airway irritation made it a common inhalation induction agent in pediatric anesthesia.[43][44] Its use indeveloped countrieshas been mostly replaced by newer anesthetic agents such assevoflurane.[45]It is not commercially available in the United States.[7]

Society and culture[edit]

Availability[edit]

It is on theWorld Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10]It is available as a volatile liquid, at 30, 50, 200, and 250 ml per container but in many developed nations is not available having been displaced by newer agents.[46]

It is the onlyinhalational anestheticcontainingbromine,which makes itradiopaque.[47]It is colorless and pleasant-smelling, but unstable in light. It is packaged in dark-colored bottles and contains 0.01%thymolas a stabilizing agent.[20]

Greenhouse gas[edit]

Owing to the presence of covalently bonded fluorine, halothane absorbs in theatmospheric windowand is therefore agreenhouse gas.However, it is much less potent than most otherchlorofluorocarbonsandbromofluorocarbonsdue to its short atmospheric lifetime, estimated at only one year vis-à-vis over 100 years for manyperfluorocarbons.[48]Despite its short lifespan, halothane still has aglobal warming potential47 times that of carbon dioxide, although this is over 100 times smaller than the most abundant fluorinated gases, and about 800 times smaller than the GWP ofsulfur hexafluorideover 500 years.[49]Halothane is believed to make a negligible contribution toglobal warming.[48]

Ozone depletion[edit]

Halothane is anozone depleting substancewith anODPof 1.56 and it is calculated to be responsible for 1% of total stratospheric ozone layer depletion.[12][13]

References[edit]

- ^Anvisa(31 March 2023)."RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial"[Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese).Diário Oficial da União(published 4 April 2023).Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2023.Retrieved16 August2023.

- ^"Halothane, USP".DailyMed.18 September 2013.Retrieved11 February2022.

- ^ab"Fluothane: FDA-Approved Drugs".U.S. Food and Drug Administration.Retrieved12 February2022.

- ^ab"Halothane".DrugBank.DB01159.

- ^abcdefghWorld Health Organization(2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.).WHO Model Formulary 2008.World Health Organization. pp. 17–8.hdl:10665/44053.ISBN9789241547659.

- ^abJames MF, Hift RJ (July 2000)."Porphyrias".British Journal of Anaesthesia.85(1): 143–53.doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.143.PMID10928003.

- ^abcd"Halothane - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses".drugs.June 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2016.Retrieved13 December2016.

- ^Bricker S (17 June 2004).The Anaesthesia Science Viva Book.Cambridge University Press. p. 161.ISBN9780521682480.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^Walker SR (2012).Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109.ISBN9789400926592.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^abWorld Health Organization(2023).The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023).Geneva: World Health Organization.hdl:10665/371090.WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^Yentis SM, Hirsch NP, Ip J (2013).Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice(5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 264.ISBN9780702053757.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^abKümmerer K (2013).Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Sources, Fate, Effects and Risks.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 33.ISBN9783662092590.

- ^abLangbein T, Sonntag H, Trapp D, Hoffmann A, Malms W, Röth EP, et al. (January 1999)."Volatile anaesthetics and the atmosphere: atmospheric lifetimes and atmospheric effects of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane".British Journal of Anaesthesia.82(1): 66–73.doi:10.1093/bja/82.1.66.PMID10325839.

- ^Lobo SA, Ojeda J, Dua A, Singh K, Lopez J (2022)."Minimum Alveolar Concentration".StatPearls.Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.PMID30422569.Retrieved9 August2022.

- ^Bezuidenhout E."The blood–gas partition coefficient".Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia.1(3): 3.eISSN2220-1173.ISSN2220-1181.Retrieved8 August2022– viaCharlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital.[dead link]

- ^"Halothane".Anesthesia General.31 October 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 16 February 2011.

- ^M Subrahmanyam, S Mohan.Safety Features in Anaesthesia Machine.Indian J Anaesth. 2013 Sep-Oct; 57(5): 472–480.doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.120143 PMCID: PMC3821264PMID: 24249880

- ^Habibollahi P, Mahboobi N, Esmaeili S, Safari S, Dabbagh A, Alavian SM (January 2018)."Halothane".LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet].PMID31643481.Retrieved27 January2021– via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ^Wark H, Earl J, Chau DD, Overton J (April 1990)."Halothane metabolism in children".British Journal of Anaesthesia.64(4): 474–481.doi:10.1093/bja/64.4.474.PMID2334622.

- ^abGyorfi MJ, Kim PY (2022)."Halothane Toxicity".StatPearls.Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.PMID31424865.Retrieved18 January2023.

- ^Hankins DC, Kharasch ED (9 May 1997). "Determination of the halothane metabolites trifluoroacetic acid and bromide in plasma and urine by ion chromatography".Journal of Chromatography B: Biomedical Sciences and Applications.692(2): 413–418.doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(96)00527-0.ISSN0378-4347.PMID9188831.

- ^Okuno T, Koutsogiannaki S, Hou L, Bu W, Ohto U, Eckenhoff RG, et al. (December 2019)."Volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane directly target and attenuate Toll-like receptor 4 system".FASEB Journal.33(12): 14528–14541.doi:10.1096/fj.201901570R.PMC6894077.PMID31675483.

- ^Sakai EM, Connolly LA, Klauck JA (December 2005). "Inhalation anesthesiology and volatile liquid anesthetics: focus on isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane".Pharmacotherapy.25(12): 1773–1788.doi:10.1592/phco.2005.25.12.1773.PMID16305297.S2CID40873242.

- ^Patel SS, Goa KL (April 1996). "Sevoflurane. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its clinical use in general anaesthesia".Drugs.51(4): 658–700.doi:10.2165/00003495-199651040-00009.PMID8706599.S2CID265731583.

- ^Paris ST, Cafferkey M, Tarling M, Hancock P, Yate PM, Flynn PJ (September 1997)."Comparison of sevoflurane and halothane for outpatient dental anaesthesia in children".British Journal of Anaesthesia.79(3): 280–284.doi:10.1093/bja/79.3.280.PMID9389840.

- ^Satuito M, Tom J (2016)."Potent Inhalational Anesthetics for Dentistry".Anesthesia Progress.63(1): 42–8, quiz 49.doi:10.2344/0003-3006-63.1.42.PMC4751520.PMID26866411.

- ^"Common Name: Halothene"(PDF).Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet(PDF).969(1). 1999 – viaNew Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services.

- ^"CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Halothane".cdc.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2015.Retrieved3 November2015.

- ^Perkins B (7 February 2005)."How does anesthesia work?".Scientific American.Retrieved30 June2016.

- ^abcHemmings HC, Hopkins PM (2006).Foundations of Anesthesia: Basic Sciences for Clinical Practice.Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 292–.ISBN978-0-323-03707-5.Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2016.

- ^abcBarash P, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan M, Stock CM, Ortega R (7 February 2013).Clinical Anesthesia, 7e: Print + Ebook with Multimedia.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 116–.ISBN978-1-4698-3027-8.Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2016.

- ^Schüttler J, Schwilden H (8 January 2008).Modern Anesthetics.Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 70–.ISBN978-3-540-74806-9.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2016.

- ^Bowery NG (19 June 2006).Allosteric Receptor Modulation in Drug Targeting.CRC Press. pp. 143–.ISBN978-1-4200-1618-5.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2016.

- ^Lewis, R.J. Sax's Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. 9th ed. Volumes 1-3. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1996., p. 1761

- ^Suckling et al.,"PROCESS FOR THE PREPARATION OF 1,1,1-TRIFLUORO-2-BROMO-2-CHLOROETHANE",US patent 2921098,granted January 1960, assigned to Imperial Chemical Industries

- ^"Halogenated Anesthetics".LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury.1(1). 1 January 2018.PMID31644158.NBK548851.

- ^Ma TG, Ling YH, McClure GD, Tseng MT (October 1990). "Effects of trifluoroacetic acid, a halothane metabolite, on C6 glioma cells".Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health.31(2): 147–158.Bibcode:1990JTEH...31..147M.doi:10.1080/15287399009531444.PMID2213926.

- ^Biermann JS, Rice SA, Fish KJ, Serra MT (September 1989)."Metabolism of halothane in obese Fischer 344 rats".Anesthesiology.71(3): 431–437.doi:10.1097/00000542-198909000-00020.PMID2774271.

- ^Eger EI (1984)."The pharmacology of isoflurane".British Journal of Anaesthesia.56(Suppl 1): 71S–99S.PMID6391530.

- ^Mueller LM (March 2021). "Medicating Anaesthesiology: Pharmaceutical Change, Specialisation and Healthcare Reform in Post-War Britain".Social History of Medicine.34(4): 1343–1365.doi:10.1093/shm/hkaa101.

- ^Bovill JG (2008). "Inhalation Anaesthesia: From Diethyl Ether to Xenon".Modern Anesthetics.Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 182. pp. 121–142.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_6.ISBN978-3-540-72813-9.PMID18175089.

- ^Niedermeyer E, da Silva FH (2005).Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1156.ISBN978-0-7817-5126-1.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2016.

- ^Himmel HM (2008). "Mechanisms involved in cardiac sensitization by volatile anesthetics: general applicability to halogenated hydrocarbons?".Critical Reviews in Toxicology.38(9): 773–803.doi:10.1080/10408440802237664.PMID18941968.S2CID12906139.

- ^Chavez CA, Ski CF, Thompson DR (July 2014). "Psychometric properties of the Cardiac Depression Scale: a systematic review".Heart, Lung & Circulation.23(7): 610–618.doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.020.PMID24709392.

- ^Yentis SM, Hirsch NP, Ip J (2013).Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A-Z: An Encyclopedia of Principles and Practice(5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 264.ISBN9780702053757.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^National formulary of India(4th ed.). New Delhi, India: Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission. 2011. p. 411.

- ^Miller AL, Theodore D, Widrich J (2022)."Inhalational Anesthetic".StatPearls.Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.PMID32119427.Retrieved18 January2023.

- ^abHodnebrog Ø, Etminan M, Fuglestvedt JS, Marston G, Myhre G, Nielsen CJ, et al. (24 April 2013)."Global warming potentials and radiative efficiencies of halocarbons and related compounds: A comprehensive review"(PDF).Reviews of Geophysics.51(2): 300–378.Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..300H.doi:10.1002/rog.20013.

- ^Hodnebrog Ø, Aamaas B, Fuglestvedt JS, Marston G, Myhre G, Nielsen CJ, et al. (September 2020)."Updated Global Warming Potentials and Radiative Efficiencies of Halocarbons and Other Weak Atmospheric Absorbers".Reviews of Geophysics.58(3): e2019RG000691.Bibcode:2020RvGeo..5800691H.doi:10.1029/2019RG000691.PMC7518032.PMID33015672.

- 5-HT3 agonists

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- General anesthetics

- Glycine receptor agonists

- Hepatitis

- Hepatotoxins

- Nicotinic antagonists

- NMDA receptor antagonists

- Organobromides

- Organochlorides

- Organofluorides

- Trifluoromethyl compounds

- Withdrawn drugs

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- Ozone depletion

- Racemic mixtures