Han languages

| Han | |

|---|---|

| Samhan | |

| Geographic distribution | Southern part ofKorea |

| Linguistic classification | Koreanic?

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | None |

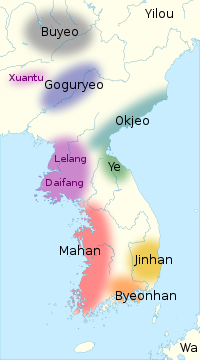

Chinese commanderies (in purple) and their eastern neighbours mentioned in theRecords of the Three Kingdoms[1] | |

TheHan languages(Korean:한어;Hanja:Hàn ngữ) orSamhan languages(삼한어;Tam Hàn ngữ) were the languages of theSamhan('three Han') of ancient southern Korea, the confederacies ofMahan,ByeonhanandJinhan. They are mentioned in surveys of the peninsula in the 3rd century found in Chinese histories, which also contain lists of placenames, but are otherwise unattested. There is no consensus about the relationships between these languages and the languages of later kingdoms.

Records

[edit]The Samhan are known from Chinese histories. Chapter 30 of theRecords of the Three Kingdoms(late 3rd century) and Chapter 85 of theBook of the Later Han(5th century) contain parallel accounts, apparently based on a common source, of peoples neighbouring theFour Commanderies of Hanin northern Korea.[2][3] TheGwanggaeto Stele(414) listsGoguryeoand Han villages, without subdividing the latter.[4]

The Chinese histories state that Jinhan had a different language from Mahan, listing some Jinhan words said to be shared with the Chinese state ofQin,from which the Jinhan claimed to be refugees (a claim discounted by most historians).[4] The two accounts differ on the relationship between the languages of Byeonhan and Jinhan, with theRecords of the Three Kingdomsdescribing them as similar, but theBook of the Later Hanreferring to differences.[5]

TheRecords of the Three Kingdomsalso gives phonographic transcriptions in Chinese characters of names of settlements, 54 in Mahan and 12 each in Byeonhan and Jinhan. Some of these names appear to include suffixes:[6][7]

- Six of the Mahan names include a suffix *-peiliai⟨ ti ly ⟩,which has been compared with the common elementpuri⟨ phu ⟩'town' in laterBaekjeplacenames andLate Middle Korean-βɨr 'town'.[6]

- Two of the Byeonhan names and one of the Jinhan names include a suffix *-mietoŋ⟨ di đông lạnh ⟩,which has been compared with Late Middle KoreanmithandProto-Japonic*mətə, both meaning 'base, bottom' and claimed bySamuel Martinto be cognate.[6]

- One of the Byeonhan names has a suffix *-jama⟨ tà mã ⟩,which is commonly identified with Proto-Japonic *jama 'mountain'.[6]

In the 4th century,Baekje,theGaya confederacyandSillaarose from Mahan, Byeonhan and Jinhan respectively.[8][9][a] Linguistic evidence from these states is sparse and, being recorded inChinese characters,difficult to interpret. Most of these materials come from Silla, whose language is generally believed to be ancestral to all extant Korean varieties as a result of theSillan unificationof most of the peninsula in the late 7th century.[11][12]

Apart from placenames, whose interpretation is controversial, data on theBaekje languageis extremely sparse:[13]

- TheBook of Liang(635) states that the language of Baekje was the same asthat of Goguryeo.[14]

- TheBook of Zhou(636) states that the Baekje gentry and commoners have different words for 'king'.[15]

- According to theSamguk sagi,the kingdom of Baekje was founded by immigrants from Goguryeo who took over Mahan.[16][17]

- The Japanese historyNihon Shoki,compiled in the early 8th century from earlier documents, including some from Baekje, records 42 Baekje words. These are transcribed asOld Japanesesyllables, which are restricted to the form (C)V, limiting the precision of the transcription. About half of them appear to beKoreanic.[18]

A single word is directly attributed to theGaya languagein theSamguk sagi(1145). It is the word for 'gate', and appears to resemble theOld Japaneseword for 'gate'.[19]

Interpretations

[edit]Different authors have offered a variety of views on the natures of these languages, based on the extant records and evidence thatPeninsular Japoniclanguages were still spoken in southern and central parts of the peninsula in the early centuries of the common era.[20] The issue is politically charged in Korea, with scholars who point out differences being accused by nationalists of trying to "divide the homeland".[21]

Based on the account of theRecords of the Three Kingdoms,Lee Ki-Moon divided the languages spoken on the Korean peninsula at that time intoPuyŏand Han groups.[22] Lee originally proposed that these were two branches of a Koreanic language family, a view that was widely adopted by scholars in Korea.[23][24][25] He later argued that the Puyŏ languages were intermediate between Korean and Japanese.[14]

Christopher Beckwithargues that the Han languages were Koreanic, and replaced the Japonic Puyŏ languages from the 7th century.[26] Alexander VovinandJames Marshall Ungerargue that the Han languages were Japonic, and were replaced by Koreanic Puyŏ languages in the 4th century.[27][28]

Based on the vocabulary in theNihon Shokiand the passage in theBook of Zhouabout words for 'king', Kōno Rokurō argued that the kingdom of Baekje was bilingual, with the gentry speaking a Puyŏ language and the common people a Han language.[15][29] Juha Janhunenargues that Baekje was Japonic speaking until Koreanic expanded from Silla.[30]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Shin (2014),pp. 16, 19.

- ^Byington & Barnes (2014),pp. 97–98.

- ^Lee & Ramsey (2011),p. 34.

- ^abWhitman (2011),p. 152.

- ^Lee & Ramsey (2011),pp. 35–36.

- ^abcdWhitman (2011),p. 153.

- ^Byington & Barnes (2014),pp. 111–112.

- ^Pai (2000),p. 234.

- ^Seth (2016),pp. 30–33.

- ^Seth (2016),p. 29.

- ^Lee & Ramsey (2000),pp. 274–275.

- ^Janhunen (2010),p. 290.

- ^Whitman (2015),p. 423.

- ^abLee & Ramsey (2011),p. 44.

- ^abVovin (2005),p. 119.

- ^Sohn (1999),p. 38.

- ^Seth (2016),p. 30.

- ^Bentley (2000),pp. 424–427, 436–438.

- ^Lee & Ramsey (2011),pp. 46–47.

- ^Whitman (2011),pp. 153–154.

- ^Lee & Ramsey (2000),p. 276.

- ^Lee & Ramsey (2011),pp. 34–36.

- ^Kim (1987),pp. 882–883.

- ^Whitman (2013),pp. 249–250.

- ^Kim (1983),p. 2.

- ^Beckwith (2004),pp. 27–28.

- ^Vovin (2013),pp. 237–238.

- ^Unger (2009),p. 87.

- ^Kōno (1987),pp. 84–85.

- ^Janhunen (2010),p. 294.

Works cited

[edit]- Beckwith, Christopher I.(2004),Koguryo, the Language of Japan's Continental Relatives,Brill,ISBN978-90-04-13949-7.

- Bentley, John R. (2000), "A new look at Paekche and Korean: data from theNihon shoki",Language Research,36(2): 417–443.

- Byington, Mark E.; Barnes, Gina (2014),"Comparison of Texts between the Accounts of Han Hàn in theSanguo zhiTam Quốc Chí, in the Fragments of theWeilüeNgụy lược, and in theHou-Han shuHậu Hán Thư "(PDF),Crossroads,9:97–112, archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2020-06-06,retrieved2020-06-06.

- Janhunen, Juha(2010),"Reconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia",Studia Orientalia,108:281–303.

- Kim, Won-yong(1983),Recent Archaeological Discoveries in the Republic of Korea,Tokyo: Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, UNESCO,ISBN978-92-3-102001-8.

- Kim, Nam-Kil (1987), "Korean", in Comrie, Bernard (ed.),The World's Major Languages,Oxford University Press, pp. 881–898,ISBN978-0-19-520521-3.

- Kōno, Rokurō (1987), "The bilingualism of the Paekche language",Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko,45:75–86.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (2000),The Korean Language,SUNY Press,ISBN978-0-7914-4831-1.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011),A History of the Korean Language,Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-1-139-49448-9.

- Pai, Hyung Il 裵 quýnh dật (2000),Constructing "Korean" Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology, Historiography, and Racial Myth in Korean State-formation Theories,Harvard University Asia Center,ISBN978-0-674-00244-9.

- Seth, Michael J. (2016),A Concise History of Premodern Korea(2nd ed.), Rowman & Littlefield,ISBN978-1-4422-6043-6.

- Shin, Michael D., ed. (2014),Korean History in Maps,Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-1-107-09846-6.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (1999),The Korean Language,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-36123-1.

- Unger, J. Marshall(2009),The role of contact in the origins of the Japanese and Korean languages,Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press,ISBN978-0-8248-3279-7.

- Vovin, Alexander(2005), "Koguryŏ and Paekche: different languages or dialects of Old Korean?",Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies,2(2): 107–140.

- ——— (2013), "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean",Korean Linguistics,15(2): 222–240,doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.03vov.

- Whitman, John (2011), "Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan",Rice,4(3–4): 149–158,doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0.

- ——— (2013), "A History of the Korean Language,by Ki-Moon Lee and Robert Ramsey ",Korean Linguistics,15(2): 246–260,doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.05whi.

- ——— (2015), "Old Korean", in Brown, Lucien; Yeon, Jaehoon (eds.),The Handbook of Korean Linguistics,Wiley, pp. 421–438,ISBN978-1-118-35491-9.