Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia

Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia Hrvatska Republika Herceg-Bosna(Croatian) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–1996 | |||||||||

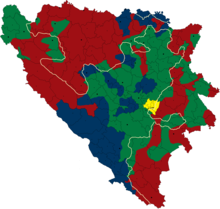

Location of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia (shown in red) within Bosnia and Herzegovina (shown in pink) | |||||||||

Herzeg-Bosnia at its greatest territorial extent in late 1995 afterOperation Southern Move

Territory controlled in October 1995

Territory claimed | |||||||||

| Status | Defunct unrecognized quasi-state in Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||||||||

| Capital | Mostar 43°20′37″N17°48′27″E/ 43.34361°N 17.80750°E | ||||||||

| Common languages | Croatian | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1991–1994 | Mate Boban | ||||||||

• 1994–1996 | Krešimir Zubak | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1993–1996 | Jadranko Prlić | ||||||||

• 1996 | Pero Marković | ||||||||

| Legislature | Assembly of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia[1] | ||||||||

| Historical era | Yugoslav Wars | ||||||||

• Community proclaimed | 18 November 1991 | ||||||||

| 6 April 1992 | |||||||||

• Declared unconstitutionala | 14 September 1992 | ||||||||

| 18 October 1992 | |||||||||

• Republic proclaimed | 28 August 1993 | ||||||||

| 18 March 1994 | |||||||||

• Formally abolished | 14 August 1996 | ||||||||

| Currency | Official:Bosnia and Herzegovina dinar Parallel:Deutsche Mark,Croatian dinar[2] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

TheCroatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia(Croatian:Hrvatska Republika Herceg-Bosna) was an unrecognized geopolitical entity andquasi-stateinBosnia and Herzegovina.It was proclaimed on 18 November 1991 under the nameCroatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia(Croatian:Hrvatska Zajednica Herceg-Bosna) as a "political, cultural, economic and territorial whole" in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and abolished on 14 August 1996.

The Croatian Community of Bosnian Posavina, proclaimed in northern Bosnia on 12 November 1991, was joined with Herzeg-Bosnia in October 1992. In its proclaimed borders, Herzeg-Bosnia encompassed about 30% of the country, but did not have effective control over the entire territory as parts of it were lost to theArmy of Republika Srpska(VRS) at the beginning of theBosnian War.The armed forces of Herzeg-Bosnia, theCroatian Defence Council(HVO), were formed on 8 April 1992 and initially fought in an alliance with theArmy of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.Their relations deteriorated throughout late 1992, which led to theCroat–Bosniak War.

The Constitutional Court of theRepublic of Bosnia and Herzegovinadeclared Herzeg-Bosnia unconstitutional on 14 September 1992. Herzeg-Bosnia formally recognized the Government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and functioned as a state within a state, while some in its leadership advocated the secession of the entity and its unification withCroatia.

On 28 August 1993, Herzeg-Bosnia was declared a republic following the proposal of theOwen-Stoltenberg Plan,envisioning Bosnia and Herzegovina as a union of three republics. Its capital city wasMostar,which was then a war zone, and the effective control center was inGrude.In March 1994, theWashington Agreementwas signed that ended the conflict betweenCroatsandBosniaks.Under the agreement, Herzeg-Bosnia was to be joined into theFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,but it continued to exist until it was formally abolished in 1996.

Etymology

[edit]

The termHerzeg-Bosnia(Croatian:Herceg-Bosna) appeared in the late 19th century and was used as a synonym forBosniaandHerzegovinawithout political connotations. It was often found in folk poems as a more poetic name for Bosnia and Herzegovina. One of the earliest mentions of the term was by Croatian writer Ivan Zovko in his 1899 bookCroatianhood in the Tradition and Customs of Herzeg-Bosnia.Croatian historianFerdo Šišićused the term in his 1908 bookHerzeg-Bosnia on the Occasion of Annexation.In the first half of the 20th century the name Herzeg-Bosnia was used by historians such asHamdija KreševljakovićandDominik Mandićand Croatian politiciansVladko MačekandMladen Lorković.Its usage decreased in the second half of the 20th century until 1991 and the proclamation of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia.[3]Since the 1990s, it has been used as a name for aCroat territorial unit in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[4]

After theWashington Agreementwas signed in March 1994 and theFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas created, one ofits cantonswas named the Herzeg-Bosnia Canton. In 1997, that name was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and officially renamedCanton 10.[5]

Background

[edit]

In early 1991, following the14th Extraordinary Congressof theCommunist Party of Yugoslavia,the leaders of the six Yugoslav republics began a series of meetings to solve the crisis inYugoslavia.The Serbian leadership favored the centralisation of the country, whereas the Croatian and Slovenian leadership favored a confederation of sovereign states or federalization.Alija Izetbegovićproposed an asymmetrical federation on 22 February, where Slovenia and Croatia would maintain loose ties with the 4 remaining republics. Shortly after that, he changed his position and opted for a sovereign Bosnia and Herzegovina as a prerequisite for such a federation.[6]On 25 March 1991, Croatian presidentFranjo Tuđmanmet with Serbian presidentSlobodan Miloševićin Karađorđevo,allegedly to discuss thepartition of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[7][8]On 6 June, Izetbegović and Macedonian presidentKiro Gligorovproposed a weak confederation between Croatia, Slovenia and a federation of the other four republics, which was rejected by Milošević.[9]

On 13 July, the government ofNetherlands,then the presiding EC country, suggested to other EC countries that the possibility of agreed changes to Yugoslav Republics borders could be explored, but the proposal was rejected by other members.[10]In July 1991,Radovan Karadžić,president of the self-proclaimedRepublika Srpska,andMuhamed Filipović,vice president of theMuslim Bosniak Organisation(MBO), drafted an agreement between the Serbs and Bosniaks which would leave Bosnia in a state union with SR Serbia and SR Montenegro. TheCroatian Democratic Union(HDZ BiH) and theSocial Democratic Party(SDP BiH) denounced the agreement, calling it an anti-Croat pact and a betrayal. Although initially welcoming the initiative, Izetbegović also dismissed the agreement.[11][12]

From July 1991 to January 1992, during theCroatian War of Independence,the JNA and Serb paramilitaries used Bosnian territory to wage attacks on Croatia.[13]The Croatian government helped arm the Croats and Bosniaks in Bosnia and Herzegovina, expecting the war to spread there.[14][13]By late 1991 about 20,000 Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, mostly from the Herzegovina region, enlisted in theCroatian National Guard.[15]During the war in Croatia, Bosnian presidentAlija Izetbegovićgave a televised proclamation of neutrality, stating that "this is not our war", and the Sarajevo government was not taking defensive measures against a probable attack by the Bosnian Serbs and the JNA.[16]Izetbegović agreed to disarm the existingTerritorial Defense(TO) forces on the demand of the JNA. This was defied by Bosnian Croats and Bosniak organizations that gained control of many facilities and weapons of the TO.[17][18]

History

[edit]Establishment

[edit]In October 1991 the Croat village ofRavnoin Herzegovina was attacked and destroyed byYugoslav People's Army(JNA) forces before turning south towards thebesiegedDubrovnik.[19]These were the first Croat casualties in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Izetbegović did not react to the attack on Ravno. The leadership of Bosnia and Herzegovina initially showed a willingness to remain in a rump Yugoslavia but later advocated for a unified Bosnia and Herzegovina.[20]

On 12 November 1991, at a meeting chaired byDario KordićandMate Boban,local party leaders of the HDZ BiH reached an agreement to undertake a policy of achieving an "age-old dream, a common Croatian State" and decided that the proclamation of aCroatian banovinain Bosnia and Herzegovina should be the "initial phase leading towards the final solution of the Croatian question and the creation of a sovereign Croatia within its ethnic and historical [...] borders."[21]On the same day, the Croatian Community of Bosnian Posavina was proclaimed in municipalities of northwest Bosnia inBosanski Brod.[22]

On 18 November, the autonomous Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia (HZ-HB) was established, it claimed it had no secession goal and that it would serve a "legal basis for local self-administration".[23]The decision on its establishment stated that the Community will "respect the democratically elected government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina for as long as exists the state independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina in relation to the former, or any other, Yugoslavia".[24]Boban was established as its president.[25]One of Boban's advisers stated that Herzeg-Bosnia was only a temporary measure and that the entire area will in the end be an integral part of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[26]From its inception the leadership of Herzeg-Bosnia and HVO held close relations to the Croatian government and theCroatian Army(HV).[27]At a session of the Supreme State Council of Croatia, Tuđman said that the establishment of Herzeg-Bosnia was not a decision to separate from Bosnia and Herzegovina. On 23 November, the Bosnian government declared Herzeg-Bosnia unlawful.[28]

On 27 December 1991, the leadership of the HDZ of Croatia and of HDZ BiH held a meeting in Zagreb chaired by Tuđman. They discussed Bosnia and Herzegovina's future, their differences in opinion on it, and the creation of a Croatian political strategy.Stjepan Kljuićfavored that Croats stay within Bosnia and Herzegovina while Boban said that, in the event of Bosnia and Herzegovina's disintegration, Herzeg-Bosnia should be proclaimed an independent Croatian territory "which will accede to the State of Croatia but only at such time as the Croatian leadership [...] should decide." Kordić, the vice president of Herzeg-Bosnia, claimed that the spirit of Croats in Herzeg-Bosnia had grown stronger since its declaration and that Croats in the Travnik region were prepared to become a part of the Croatian State "at all costs [...] any other option would be considered treason, save the clear demarcation of Croatian soil in the territory of Herzeg-Bosnia."[29]At the same meeting, Tuđman said that "from the perspective of sovereignty, Bosnia-Herzegovina has no prospects" and recommended that Croatian policy should be one of "support for the sovereignty [of Bosnia and Herzegovina] until such time as it no longer suits Croatia."[30]He based this on the belief that the Serbs did not accept Bosnia and Herzegovina and that Bosnian representatives did not believe in it and wished to remain in Yugoslavia,[31]and thought that such a policy would avoid war.[32]Tuđman declared "it is time that we take the opportunity to gather the Croatian people inside the widest possible borders".[33]

Bosnian War

[edit]

Between 29 February and 1 March 1992, anindependence referendumwas held inSR Bosnia and Herzegovina.[34]The referendum question was: "Are you in favor of a sovereign and independent Bosnia-Herzegovina, a state of equal citizens and nations of Muslims, Serbs, Croats and others who live in it?"[35]Independence was strongly favoured by Bosniak and Bosnian Croat voters, but the referendum was largely boycotted byBosnian Serbs.The total turnout of voters was 63.6%, of which 99.7% voted for the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[36]

On 8 April 1992, theCroatian Defence Council(HVO) was formed and was the official military of Herzeg-Bosnia.[8]A sizable number of Bosniaks also joined the HVO,[14]constituting between 20 and 30 percent of the army.[37]The legal rationale for the formation of HVO was seen in the laws of Yugoslavia that allowed citizens to organize their own self-defence when their government was unable or unwilling to defend them. Boban said that the HVO was formed because "thirteen Croatian villages in the municipality of Trebinje – including Ravno – were destroyed and the Bosnian government did nothing thereafter".[16]

At the beginning of the war, a Croat-Bosniak alliance was formed, but over time there were notable breakdowns of it due to rising tensions and the lack of mutual trust,[38]with each of the two sides holding separate discussions with the Serbs, and soon there were complaints from both sides against the other.[39]The designated capital of Herzeg-Bosnia,Mostar,wasbesiegedby the JNA and later theArmy of Republika Srpska(VRS) from April 1992. In late May, the HVO launched a counter-offensive and, after more than a month of fighting, managed to suppress the VRS forces from Mostar and the surrounding area.[40]

The Croatian and Herzeg-Bosnia leadership offered Izetbegović aconfederationof Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, but Izetbegović rejected it.[26]On 3 July 1992, the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia was formally declared, in an amendment to the original decision from November 1991.[41][26]It adopted theCroatian dinaras its currency andCroatianas the official language. It had its own school curriculum and a local government system.[42]In the preamble it was attested:[43]

"Faced with the ruthless aggression of the Yugoslav Army and Chetniks against the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Croatia, with the tremendous number of lives lost, with the suffering and pain, with the fact that age-old Croatian territories and goods are being coveted, with the destruction of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and its legally elected bodies, the Croatian people of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in these difficult moments of their history when the last Communist army of Europe, united with the Chetniks, is endangering the existence of the Croatian people and the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, are deeply aware that their future lies with the future of the entire Croatian people."

On 21 July 1992, theAgreement on Friendship and Cooperation between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatiawas signed by Alija Izetbegović and Franjo Tuđman, establishing a military cooperation between Bosnian and Croatian forces.[44]Although it was often not harmonious, it resulted in the gradual stabilisation of the defence in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Weapons for the Bosnian army were sent through Croatia despite the arms embargo.[14]At a session held on 6 August, the Bosnian Presidency accepted HVO as an integral part of the Bosnian armed forces.[45]

On 14 September 1992, theConstitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovinadeclared the proclamation of Herzeg-Bosnia unconstitutional.[46]The Croatian Community of Bosnian Posavina was formally joined into Herzeg-Bosnia in October 1992.[22]Throughout late 1992, tensions between Croats and Bosniaks increased and in early 1993 theCroat–Bosniak Warescalated.[47]Clashes spread in central Bosnia, particularly in theLašva Valley.[48]Within two months most of central Bosnia was under ARBiH control.

In late July 1993 the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan was proposed by U.N. mediatorsThorvald StoltenbergandDavid Owenthat would organize Bosnia and Herzegovina into a union of three ethnic republics.[49]Serbs would receive 53 percent of the territory, Bosniaks would receive 30 percent, and Croats 17 percent. The Croats accepted the proposal, although they had some objections regarding the proposed borders. The Serbs also accepted the proposal, while the Bosniak side rejected the plan, demanding territories in eastern and western Bosnia from the Serbs and access to theAdriatic Seafrom the Croats. On 28 August, in accordance with the Owen-Stoltenberg peace proposal, the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia was proclaimed in Grude as a "republic of the Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina".[50]However, it was not recognised by the Bosnian government.[51]

Washington Agreement

[edit]On 26 February 1994 talks began inWashington, D.C.between the Bosnian government leaders andMate Granić,CroatianMinister of Foreign Affairsto discuss the possibilities of a permanent ceasefire and a confederation of Bosniak and Croat regions.[52]By this time the amount of territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina controlled by the HVO had dropped from 20 percent to 10 percent.[53][54]Boban and HVO hardliners were removed from power[55]while "criminal elements" were dismissed from theArmy of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina(ARBiH).[56]Under strong American pressure,[55]a provisional agreement on aCroat-Bosniak Federationwas reached in Washington on 1 March. On 18 March, at a ceremony hosted by US PresidentBill Clinton,Bosnian Prime MinisterHaris Silajdžić,Croatian Foreign Minister Mate Granić and President of Herzeg-BosniaKrešimir Zubaksigned the ceasefire agreement. The agreement was also signed by Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović and Croatian President Franjo Tuđman. Under this agreement, the combined territory held by the Croat and Bosnian government forces was divided into ten autonomous cantons. It effectively ended the Croat-Bosniak War.[52]

Aftermath

[edit]

In November 1995 theDayton Agreementwas signed by presidents of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia that ended the Bosnian war. TheFederation of Bosnia and Herzegovina(FBiH) was defined as one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina and comprised 51% of the territory. TheRepublika Srpska(RS) comprised the other 49%. However, there were problems with its implementation due to different interpretations of the agreement.[57]AnArmy of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas to be created by merging units from the ARBiH and the HVO, though this process was largely ineffective.[58]The Federation was divided into 10 cantons. Croats were a majority in three of them and Bosniaks in five. Two cantons were ethnically mixed, and in municipalities that were divided during the war parallel local administrations remained. The return of refugees was to begin in those cantons.[59]The agreement stipulated that Herzeg-Bosnia be abolished within two weeks.[60]

The Federation acted only on paper and failed to function as a working government, despite the pressure from Washington and with presidents Tuđman and Izetbegović assuring that Croat and Bosniak politicians would join together in the new government. On 14 August 1996, it was agreed that Herzeg-Bosnia would be formally abolished by the end of that month.[61]On 24 May 1997, theCroatian Community of Herzeg-Bosniaassociation was founded in Neum as the main institution of Croats in the country.[62]

According to a 1999 report by theEuropean Stability Initiative(ESI), Herzeg-Bosnia structures continued to function and a parallel government acted to expand the independence of its financial institutions. HDZ leaders claimed that "the Herzeg-Bosnia side could not accept a common financial system, because such a system did not allow the Bosnian Croats to finance their own army and to follow up on their own social obligations in the long term."[63]Parallel Herzeg-Bosnia budgetary systems collect revenue from Croat-controlled cantons. The Herzeg-Bosnia Payments Bureau controls Croat economic activity and there are separate Croat public utilities, social services, social insurance funds, and forestry administrations. A segregated education system with a Herzeg-Bosnia curriculum and textbooks from Croatia is maintained.[64]According to the ESI report, Herzeg-Bosnia continued receiving financial support from Croatia, particularly theMinistry of Defence.The pension and education systems and the salaries of Croat politicians and military officers are subsidized by the Croatian government.[65]AnOrganization for Security and Co-operation in Europe(OSCE) report two years after the end of the war concluded that Herzeg-Bosnia became "in every respect, from military and security matters to business ties, part of Croatia."[66][67]

Area and population

[edit]

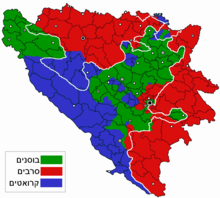

The Croatian Communities of Bosnian Posavina and Herzeg-Bosnia within its proclaimed borders in November 1991 extended at about 30% of Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to the 1991 census, in that territory, there were 1,238,512 people with ethnicities as follows.[68]

- Croats– 556,274 (44.91%)

- Muslims– 398,092 (32.14%)

- Serbs– 203,612 (16.44%)

- Yugoslavs– 56,092 (4.53%)

- Others – 24,505 (1.98%)

During the initial negotiations organized by the international community, the Croatian side advocated for a Croat national unit at some 30% of Bosnia and Herzegovina – slightly altered borders of the Croatian Communities, but with Croat enclaves around Žepče, Banja Luka and Prijedor included.[68]

This maximalist approach was done for a better position during negotiations, which would inevitably reduce the excessive demands to an optimal envision of a Croat unit. Based on later statements of Herzeg-Bosnia leading officials, the optimal range of a Croat territorial unit was within the borders of the 1939 Banovina of Croatia, thus excluding Bosniak and Serb majority areas on the outskirts of Herzeg-Bosnia. Those borders would include around 26% of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ethnic composition of this area in 1991 was:[69]

- Croats – 514,228 (50.94%)

- Muslims – 291,232 (28.85%)

- Serbs – 141,805 (14.05%)

- Yugoslavs – 44,043 (4.36%)

- Others – 18,191 (1.80%)

At the beginning of the war, JNA and VRS forces gained control of Serb-majority areas that were proclaimed part of Herzeg-Bosnia. By late 1992 Herzeg-Bosnia lost Kupres, most of Bosnian Posavina, and Jajce to VRS.[70]The territory under the authority of Herzeg-Bosnia became limited to Croat ethnic areas in around 16% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[71]The arrival of Bosniak refugees from areas captured by the VRS to HVO-controlled parts of central Bosnia and Mostar altered the ethnic structure and reduced the share of Croats.[72][73]

Economy

[edit]In the late 1980s and early 1990s, theSocialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovinawas the poorest republic of the SFR Yugoslavia, along withSocialist Republic of Macedonia.Infrastructure and industry were poorly developed. The economy of Bosnia and Herzegovina totally faded during theBosnian War.Many companies, which were successful before the war, were robbed and destroyed just at the beginning of the war. There was no economic activity due to the Yugoslav wars. Agricultural output was diminished, the traffic infrastructure was in collapse, construction was almost non-existent, and unemployment was very high. As a result of the wars, between 1992 and 1995, industrial production declined by 80% and an already poor infrastructure declined further. Croats left the war the most prosperous. Former Yugoslav companies were left without headquarters which were located on the territory of Herzeg-Bosnia. All banks were based inSarajevo.[74][75]

Herzeg-Bosnia did not have a central bank. Credits were obtained from local commercial banks, meaning that the deficit was financed by the real sector and the households sector.[76]Foreign banking branches had to legally close their operations and reregister as new banks in Bosnia and Herzegovina after it declared independence.[77]The most important bank in Herzeg-Bosnia was Hrvatska banka d.d. Mostar. The second largest bank was Hrvatska poštanska banka.[78]The official currency in the territory of Herzeg-Bosnia was theBosnia and Herzegovina dinar,but two parallel currencies were also in use: theDeutsche Markand theCroatian dinar(later theCroatian kuna).[2]

Reconstruction in most of Herzeg-Bosnia resumed shortly after the Washington Agreement was signed.[79]Civilian employment in Herzeg-Bosnia in 1994 was around 20% of its pre-war level.[80]In 1995, the industrial production growth rate in Croat-majority areas was 25%, average wages grew by 35%, and employment growth was 69%. The highest growth was recorded in the production of concrete. The average monthly wage was 250 DEM and each employee received a monthly food supplement of 50 DEM. Unemployment was estimated at 50% of the total labor force in mid-1995.[81]GDP growth in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was estimated at 28% in 1995, fueled by the renewal of the Croat-Bosniak alliance, while GDP in Republika Srpska declined by 23%.[80]

Military

[edit]

The Croatian Defence Council (Croatian:Hrvatsko vijeće obrane,HVO) was formed on 8 April 1992 and was the official military of Herzeg-Bosnia, although the organization and arming of Bosnian Croat military forces began in late 1991. Each district of Herzeg-Bosnia was responsible for its own defence until the formation of four Operative Zones with headquarters in Mostar, Tomislavgrad, Vitez and Orašje. However, there were always problems in coordinating the Operative Zones. On 15 May 1992, the HVO Department of Defense was established. By that time the HVO Main Staff, Main Logistics Base, Military Police, and Personnel Administration were also formed.[82]The backbone of the HVO were its brigades formed in late 1992 and early 1993. Their organization and military equipment was relatively good, but could only conduct limited and local offensive action. The brigades usually had three or four subordinate infantry battalions with light artillery, mortars, antitank and support platoons. A brigade numbered between a few hundred to several thousand men, but most had 2–3,000.[83][84]In early 1993 the HVO Home Guard was formed in order to provide support for the brigades.[85]The HVO forces became better organized as time passed by, but they started creating guards brigades, mobile units of professional soldiers, only in early 1994.[86]The European Community Monitoring Mission (ECMM) estimated the strength of the HVO in the beginning of 1993 at 45,000–55,000.[87]In July 1993, CIA estimated the HVO forces at 40,000 to 50,000 men.[88]

Culture

[edit]The Government of Herzeg-Bosnia founded the National Theatre in 1993 in Mostar. From 1994 it had the title ofCroatian National Theatre in Mostarand was the first one with the prefix Croatian. The first play performed in this theatre wasA Christmas Fable(Božićna bajka) by Mate Matišić. The foundations of a new building were laid in January 1996.[89]

Education

[edit]The Ministry of Education of Herzeg-Bosnia adoptedCroatianas the official language and followed the education programme of Croatian schools. As the war escalated, teaching in schools and theUniversity of Mostarwas suspended in May 1993 for the remainder of the academic year. TheFaculty of Pedagogyof the University of Mostar, located in western Mostar, temporarily moved its facilities to the towns ofŠiroki BrijegandNeumwhere there were no major armed conflicts. It returned to Mostar in 1994.[90]

Sport

[edit]Organized football competitions in Bosnia and Herzegovina were cancelled in 1992 due to the war. TheFirst League of Herzeg-Bosniaas the top football league started on 20 April 1994 and was divided into two groups. The League was organized by theFootball Federation of Herzeg Bosnia.The winner of the first season, that was played only in Spring, wasNK Mladost-Dubint Široki Brijeg.The league was played for seven years, with NK Široki Brijeg winning five andNK Posušjetwo trophies.[91]

Legacy

[edit]

Since 2005, there have been attempts byirredentiststo restore Herzeg-Bosnia by creating a new third entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was started under the leadership ofIvo Miro Jović,as he said "I don't mean to reproach Bosnian Serbs, but if they have a Serb republic, then we should also create a Croat republic and Bosniak (Muslim) republic". The Croat representative on the federal Bosnian Presidency,Željko Komšić,opposed this, but some Bosnian Croat politicians advocated for the establishment of a third (Croatian) entity.[92]

Dragan Čović,president of one of the main Croatian parties in Bosnia,Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina(HDZ BiH), said that "all Croatian parties will propose that Bosnia and Herzegovina be divided into three ethnic entities, withSarajevoas a separate district. Croatian politicians must be the initiators of a new constitution which would guarantee Croats the same rights as to other constituent peoples. Every federal unit would have its legislative, executive and judiciary organs ". He claimed the two-entity system is untenable and that Croats have been subject to assimilation and deprived of basic rights in the federation with Bosniaks.[93]

Petar Matanović, president of theCroatian National Council,opposed creating a third entity, claiming that the division of Bosnia into four federal units (three proposed ethnically-based entities plus Sarajevo as a neutral capital entity) would lead to a new war. He added that "we have to establish the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina in accordance with European standards and then regulate entities. It seems to me that thisagreemententails an intention to strengthen entities and weaken the country. "[94]Stjepan Mesić,former president ofCroatia,opposed the creation of a third entity, stating that: "if the current division of Bosnia Herzegovina into two entities does not function, it will not function with divisions into three entities".[95]

In 2009,Miroslav Tuđman,son of the late Franjo Tuđman, called for the establishment of a Croatian entity.[96][97]Čović stated, "We want to live in Bosnia-Herzegovina where Croats will be equal to the other two peoples according to the Constitution."[98]

In 2013, six political and military leaders of Herzeg-Bosnia,Jadranko Prlić,Bruno Stojić,Slobodan Praljak,Milivoj Petković,Valentin Ćorić,andBerislav Pušić,were convicted in a first instance verdict by the ICTY for being part of ajoint criminal enterprise(JCE) against the non-Croat population of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ICTY also ruled, by a majority, that Tuđman, Šušak and Boban were part of a JCE, whose goal was to annex or control territory that was part of theBanovina of Croatiain 1939.[99]Judge Jean-Claude Antonetti, the presiding judge in the trial, issued a separate opinion in which he contested the notion of a joint criminal enterprise.[100]

Slobodan Praljak and others (Prlić, Stojić, Petković, Ćorić and Pušić) were found guilty of committing violations of the laws of war, crimes against humanity and breaches of the Geneva Conventions during the Croat–Bosniak War by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in November 2017.[101]

In February 2017,Croatian Peasant Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina's presidentMario Karamatićsaid his party will demand a reestablishment of Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia in its 1995 shape if theRepublika Srpska secedes.[102]Karamatić declared Croats have been "fooled" by the 1994Washington Agreementthat abolished Herzeg-Bosnia and established theCroat-Bosniak Federation,which was also "broken" numerous times and that Croats have the right to recede to thestatus quo ante,i.e., Herzeg-Bosnia.[103]As far as the Herzeg-Bosnia's tentative territory, Karamatić proposed the area served by the electricity utilityElektroprivreda HZ HB,[104]which covers most areas of Croat habitation.[105]

18 November is celebrated as the holiday inWest Herzegovina Cantonas theday of Herzeg-Bosnia's foundation.[106]One of the cantons of the Federation used the name "Herzeg-Bosnian Canton",but this name was deemedunconstitutionalby the Federation Constitutional Court, and it is officially referred to asCanton 10.[5]A memorial plaque in honor of Herzeg-Bosnia andMate Bobanwas placed in downtownGrude.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^"A NEW LEADER OF THE CROATS IN B&H".

- ^abCvikl 2008,p. 124.

- ^Nuić & 28 July 2009.

- ^Herceg-BosnaArchived2016-08-03 at theWayback Machine–Croatian Encyclopedia

- ^ab"U-11/97".Archived fromthe originalon April 19, 2008.RetrievedJune 8,2009.

- ^Ramet 2006,p. 386.

- ^Ramet 2010,p. 263.

- ^abTanner 2001,p. 286.

- ^Tanner 2001,p. 248.

- ^Owen 1996,pp. 32–34.

- ^Ramet 2006,p. 426.

- ^Schindler 2007,p. 71.

- ^abLukic & Lynch 1996,p. 206.

- ^abcGoldstein 1999,p. 243.

- ^Hockenos 2003,pp. 91–2.

- ^abShrader 2003,p. 25.

- ^Shrader 2003,p. 33.

- ^Malcolm 1995,p. 306.

- ^Marijan 2004,p. 255.

- ^Krišto 2011,p. 43.

- ^Kordić & Čerkez Judgement 2001,p. 141.

- ^abTomas & Nazor 2013,p. 281.

- ^Ramet 2010,p. 264.

- ^Marijan 2004,p. 259.

- ^Toal & Dahlman 2011,p. 105.

- ^abcMalcolm 1995,p. 318.

- ^Calic 2012,p. 127.

- ^Prlic et al. judgement vol.1 2013,p. 150.

- ^Kordić & Čerkez Judgement 2001,p. 142.

- ^Ramet 2010,p. 265.

- ^Krišto 2011,p. 47.

- ^Krišto 2011,p. 46.

- ^Prlic et al. judgement 2013,pp. 151–2.

- ^Nohlen & Stöver 2010,p. 330.

- ^Velikonja 2003,p. 237.

- ^Nohlen & Stöver 2010,p. 334.

- ^Mulaj 2008,p. 53.

- ^Christia 2012,p. 154.

- ^Marijan 2004,p. 269.

- ^Malcolm 1995,p. 317.

- ^Dyker & Vejvoda 2014,p. 103.

- ^Christia 2012,p. 182.

- ^Prlic et al. judgement vol.6 2013,pp. 396–397.

- ^Ramet 2006,p. 463.

- ^Marijan 2004,p. 270.

- ^Paul R. Bartrop (2012).A Biographical Encyclopedia of Contemporary Genocide: Portraits of Evil and Good.ABC-CLIO. p. 44.ISBN9780313386794.

- ^Christia 2012,pp. 157–158.

- ^Tanner 2001,p. 290.

- ^Marijan 2004,p. 261.

- ^Klemenčić, Pratt & Schofield 1994,pp. 57–59.

- ^Owen-Jackson 2015,p. 74.

- ^abBethlehem & Weller 1997,p. liv.

- ^Magaš & Žanić 2001,p. 66.

- ^Hoare 2010,p. 129.

- ^abTanner 2001,p. 292.

- ^Christia 2012,p. 177.

- ^Goldstein 1999,p. 255.

- ^Schindler 2007,p. 252.

- ^Toal & Dahlman 2011,p. 196.

- ^Gosztonyi 2003,p. 53.

- ^Perlez & 15 August 1996.

- ^Anđelić 2009,p. 9.

- ^ESI & 14 October 1999,pp. 7–8.

- ^ESI & 14 October 1999,pp. 8–9.

- ^ESI & 14 October 1999,p. 9.

- ^Moore 2013,p. 95.

- ^Burg & Shoup 1999,p. 377.

- ^abMrduljaš 2009,p. 831.

- ^Mrduljaš 2009,pp. 833–834.

- ^Mrduljaš 2009,p. 838.

- ^Mrduljaš 2009,p. 837.

- ^Tanner 2001,p. 287.

- ^Shrader 2003,p. 3.

- ^Zupcevic, Merima (September 2009)."CASE STUDY: BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA"(PDF).web.worldbank.org.

- ^"Summary of the ICTY Judgment on Gneral Blaskic. ICTY, 03 March 2000".phdn.org.Retrieved2022-12-16.

- ^Cvikl 2008,p. 148.

- ^Cvikl 2008,p. 141.

- ^IMF 1996,p. 37.

- ^IMF 1996,p. 38.

- ^abCvikl 2008,p. 189.

- ^Cvikl 2008,p. 191.

- ^Shrader 2003,pp. 25–27.

- ^Shrader 2003,p. 30.

- ^CIA 1993,p. 47.

- ^Shrader 2003,p. 31.

- ^Shrader 2003,p. 29.

- ^Shrader 2003,p. 22.

- ^CIA 1993,p. 28.

- ^Komadina 2014,p. 103.

- ^Owen-Jackson 2015,p. 114.

- ^"NK Široki Brijeg – Povijest kluba".NK Široki Brijeg.Archivedfrom the original on 20 March 2016.Retrieved28 April2016.

- ^Staff."Bosnia: Regionalization proposal on table".B92. Archived fromthe originalon 22 February 2014.Retrieved27 April2015.

- ^"BOSNIA: 'Sanctions if no progress on reform', warns top envoy's deputy".ADN Kronos International. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved13 August2015.

- ^Petar Matanović commentsArchived2018-09-04 at theWayback Machine,javno; accessed 27 April 2015.

- ^Stjepan Mesić commentsArchivedMarch 9, 2009, at theWayback Machine,javno; accessed 27 April 2015.

- ^[1]Archived2009-12-08 at theWayback Machine,dnevniavaz.ba; accessed 28 April 2015.(in Croatian)

- ^[2]Archived2015-07-02 at theWayback Machine,sabahusa; accessed 28 April 2015(in Croatian)

- ^[3]Archived2009-12-13 at theWayback MachineArchived2009-12-13 at theWayback Machine,b92.net; accessed 27 April 2015.

- ^Prlic et al. judgement 2013.

- ^Prlic et al. judgement vol.6 2013,p. 212, 374, 377.

- ^"Trial Judgement Summary for Prlić et al"(PDF).ICTY. 29 November 2017.Archived(PDF)from the original on 10 April 2018.Retrieved27 March2019.

- ^"HSS will demand re-establishment of HR-HB in case of secession of RS"Archived2017-02-23 at theWayback Machine,fena.ba, 22.02.2017.

- ^"KARAMATIĆ: KUD' STRUJA, TUD' I REFERENDUM!"Archived2017-02-23 at theWayback Machine,starmo.ba, February 22nd, 2017

- ^"Beljak u Mostaru: Hrvati Herceg-Bosne bili su na braniku Hrvatske, a ona ih je ignorirala 100 godina"Archived2017-02-23 at theWayback Machine,RADIO LJUBUŠKI, February 22nd, 2017

- ^Bosnia's Future, p. 37

- ^18 November commemorationArchived2011-07-17 at theWayback Machine,uip-zzh; accessed 27 April 2015.

References

[edit]Books and journals

[edit]- Anđelić, Ivan (2009).Hrvatska zajednica Herceg-Bosna 1997. – 2009[Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia 1997 – 2009](PDF).Mostar: Hrvatska zajednica Herceg Bosna. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2018-02-10.Retrieved2016-12-29.

- Bethlehem, Daniel; Weller, Marc (1997).The Yugoslav Crisis in International Law.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521463041.

- Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (1999).The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention.Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.ISBN978-0-7656-3189-3.

- International Monetary Fund(1996).Bosnia and Herzegovina, recent economic developments.International Monetary Fund.ISBN9781452773773.

- Calic, Marie–Janine (2012). "Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes, 1991–1995". In Ingrao, Charles; Emmert, Thomas A. (eds.).Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative(2nd ed.). West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 114–153.ISBN978-1-55753-617-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency,Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002).Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 1.Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency.ISBN978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency,Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002).Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 2.Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency.ISBN978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency(1993).Combatant Forces in the Former Yugoslavia(PDF).Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency.

- Christia, Fotini(2012).Alliance Formation in Civil Wars.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1-13985-175-6.

- Cvikl, Milan Martin (2008).Analysis of the Economic Measures & Developments in the HZ/HR HB Within the Context of the Economic Environment in BiH 1991–1994.Ljubljana:International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

- Dyker, David A.; Vejvoda, Ivan (2014).Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth.New York City: Routledge.ISBN9781317891352.

- Goldstein, Ivo(1999).Croatia: A History.London: C. Hurst & Co.ISBN978-1-85065-525-1.

- Gosztonyi, Kristóf (2003). "Non-Existent States with Strange Institutions". In Koehler, Jan; Zürcher, Christoph (eds.).Potentials of Disorder: Explaining Conflict and Stability in the Caucasus and in the Former Yugoslavia.Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 46–61.ISBN9780719062414.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-03.Retrieved2016-09-27.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.).Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136.ISBN978-1-139-48750-4.

- Hockenos, Paul (2003).Homeland Calling: Exile Patriotism and the Balkan Wars.Ithaca: Cornell University Press.ISBN978-0-8014-4158-5.

- Klemenčić, Mladen; Pratt, Martin; Schofield, Clive H. (1994).Territorial Proposals for the Settlement of the War in Bosnia-Hercegovina.IBRU.ISBN9781897643150.

- Komadina, Dragan (2014)."A Short history of Croatian theatre in Bosnia and Herzegovina".Croatian Studies Review.9.Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History: 98–104.

- Krišto, Jure (April 2011)."Deconstructing a myth: Franjo Tuđman and Bosnia and Herzegovina".Review of Croatian History.6(1). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History: 37–66.

- Lukic, Reneo; Lynch, Allen (1996).Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-829200-5.

- Magaš, Branka; Žanić, Ivo (2001).The War in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina 1991–1995.London: Frank Cass.ISBN978-0-7146-8201-3.

- Malcolm, Noel(1995).Povijest Bosne: kratki pregled[Bosnia: A Short History]. Erasmus Gilda.ISBN9783895470820.

- Marijan, Davor (2004)."Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991–1995)".Journal of Contemporary History.36.Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History: 249–289.

- Moore, Adam (2013).Peacebuilding in Practice: Local Experience in Two Bosnian Towns.Ithaca: Cornell University Press.ISBN978-0-8014-5199-7.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-03-12.Retrieved2016-03-23.

- Mrduljaš, Saša (2009)."Hrvatska politika unutar Bosne i Hercegovine u kontekstu deklarativnog i realnoga opsega Hrvatska zajednice / republike Herceg-Bosne"[Croatian policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the context of declarative and real extent of the Croatian Community / Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia].Journal for General Social Issues(in Croatian).18.Split, Croatia: Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar: 825–850.

- Mulaj, Kledja (2008).Politics of Ethnic Cleansing: Nation-State Building and Provision of Insecurity in Twentieth-Century Balkans.Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN9780739146675.

- Nohlen, Dieter;Stöver, Philip (2010).Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook.Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft Mbh & Co.ISBN978-3-8329-5609-7.

- Owen, David(1996).Balkan Odyssey.London: Indigo.ISBN9780575400290.

- Owen-Jackson, Gwyneth (2015).Political and Social Influences on the Education of Children: Research from Bosnia and Herzegovina.New York: Routledge.ISBN9781317570141.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006).The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005.Bloomington: Indiana University Press.ISBN978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). "Politics in Croatia since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.).Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 258–285.ISBN978-1-139-48750-4.

- Schindler, John R. (2007).Unholy Terror: Bosnia, Al-Qa'ida, and the Rise of Global Jihad.New York City: Zenith Press.ISBN9780760330036.

- Shrader, Charles R. (2003).The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia: A Military History, 1992–1994.College Station, Texas:Texas A&M University Press.ISBN978-1-58544-261-4.

- Tanner, Marcus (2001).Croatia: A Nation Forged in War.New Haven: Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-09125-0.

- Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011).Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal.New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-973036-0.

- Tomas, Mario; Nazor, Ante (October 2013)."Prikaz i analiza borbi na bosanskoposavskom bojištu 1992"[Analysis of the Military Conflict on the Bosnian-Posavina Battlefront in 1992].Scrinia Slavonica.13(1). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Historical Institute – Department of History of Slavonia, Srijem and Baranja: 277–315.ISSN1848-9109.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003).Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina.College Station: Texas A&M University Press.ISBN978-1-58544-226-3.

News articles

[edit]- Nuić, Tihomir (28 July 2009)."Zašto Herceg-Bosna?"[Why Herzeg-Bosnia?].Ljubuški portal.Archived fromthe originalon 30 July 2017.Retrieved9 May2016.

- Perlez, Jane (15 August 1996)."Muslim and Croatian Leaders Approve Federation for Bosnia".New York Times.

International, governmental, and NGO sources

[edit]- "Prosecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez Judgement"(PDF).International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2001.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement Summary"(PDF).International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 1 of 6"(PDF).International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 6 of 6"(PDF).International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- Reshaping International Priorities In Bosnia And Herzegovina – Part I – Bosnian Power Structures(PDF)(Report). European Stability Initiative. 14 October 1999.Archived(PDF)from the original on 1 October 2018.Retrieved10 March2016.

External links

[edit]- Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia

- Bosnian War

- Former unrecognized countries

- History of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- History of the Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Separatism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1992 establishments in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1994 disestablishments in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- States and territories established in 1992

- States and territories disestablished in 1994

- Politics of Yugoslavia

- Administrative divisions of Yugoslavia

- Former subdivisions of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Former republics in Europe