High-speed rail in China

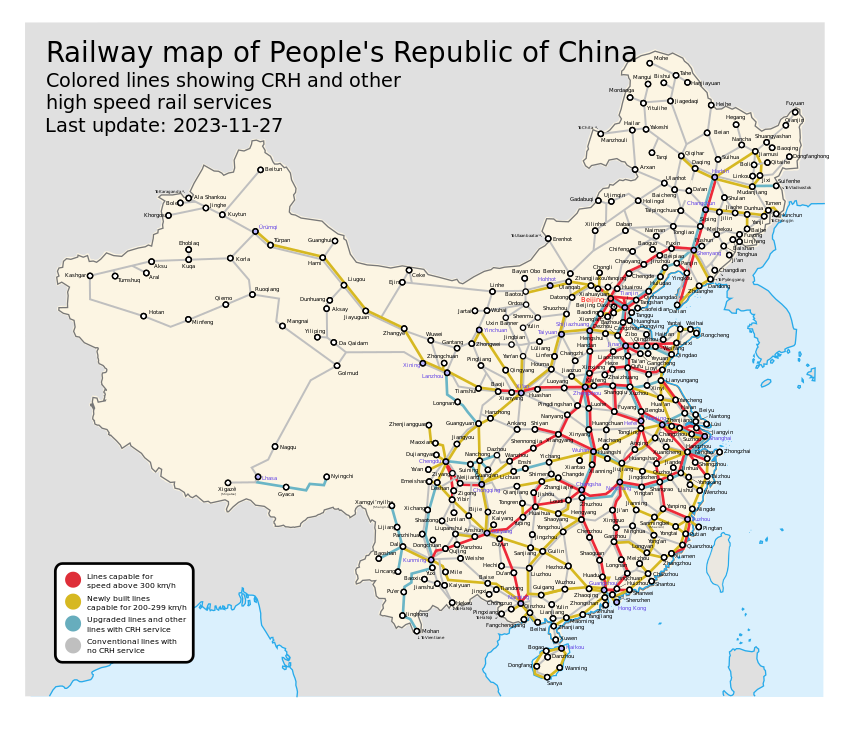

Thehigh-speed rail(HSR) network in thePeople's Republic of China(PRC) is theworld's longestand most extensively used – with a total length of 46,000 kilometres (29,000 mi) in the middle of 2024.[1][2][3]The HSR network encompasses newly built rail lines with a design speed of 200–380 km/h (120–240 mph).[4]China's HSR accounts for two-thirds of the world's total high-speed railway networks.[5][6]Almost all HSR trains, track and service are owned and operated by theChina Railway Corporationunder the brandChina Railway High-speed(CRH).

High-speed rail developed rapidly in China since the mid-2000s. CRH wasintroduced in April 2007and theBeijing-Tianjin intercity rail,which opened in August 2008, was the first passenger dedicated HSR line. Currently, the HSR extends to allprovincial-level administrative divisionsandHong Kong SARwith the exception ofMacau SAR.[note 1][note 2][note 3]

Notable HSR lines in China include theBeijing–Kunming high-speed railwaywhich at 2,760 km (1,710 mi) is the world's longest HSR line in operation, and theBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railwaywith the world's fastest operating conventional train services. TheShanghai Maglevis the world's first high-speed commercialmagnetic levitation(maglev) line that reach a top speed of 431 km/h (268 mph).[8]

The economics of high-speed rail in China has been a topic of much discussion.[9][10]A 2019 study produced by TransFORM, a knowledge platform developed by theWorld BankandChina’s Ministry of Transport,estimated the annual rate of economic return of China's high-speed rail network in 2015, to be at 8 percent, which is well above theopportunity costof capital in China for major long term infrastructure investments. The study also noted a range of benefits which included shortened travel times, improved safety and better facilitation of tourism, labor and mobility, as well as reducing highway congestion, accidents and greenhouse emissions as some automobile travellers switch from car use to rail.[11][12]A 2020 study byPaulson Institutehas estimated the net benefit of the high-speed rail system to be approximately $378 billion, with an annualreturn on investmentof 6.5%.[13]

Definition and terminology

[edit]High-speed rail in China is officially defined as "newly-built passenger-dedicated rail lines designed forelectrical multiple unit (EMU) train setstraveling at not less than 250 km/h (155 mph) (including lines with reserved capacity for upgrade to the 250 km/h (155 mph) standard) on which initial service operate at not less than 200 km/h (124 mph). "[14]EMU train sets have no more than 16railcarswithaxle loadnot greater than 17tonnesand aheadwayof three minutes or less.[14]

Thus, high-speed rail service in China requires high-speed EMU train sets to be providing passenger service on high speed rail lines at speeds of not less than 200 km/h (124 mph). EMU trains operating on non-high speed track or otherwise but at speeds below 200 km/h (124 mph) are not considered high-speed rail. Certain mixed use freight and passenger rail lines, that can be upgraded for train speeds of 250 km/h (155 mph), with current passenger service of at least 200 km/h (124 mph), are also considered high-speed rail.[14]

In common parlance, high-speed train service in China generally refers to G-, D- and C-class passenger train service.

- G-class(Cao thiết;gāotiě;'high speed rail') train service generally features EMU trains running on passenger-dedicated high-speed rail lines and operating at top speeds of at least 250 km/h (155 mph). For example, the G7 train fromBeijing SouthtoShanghai Hongqiao,which runs on theBeijing–Shanghai HSR,a line with an operating speed of 350 km/h (217 mph).

- D-class (Động xe;dòngchē;'electrical multiple unit') train service features EMU trains running at lower speeds, whether on high-speed or non-high-speed track. D-class trains can vary widely in actual trip speed. The non-stop D211 train fromGuiyang EasttoGuangzhou Southon theGuiyang–Guangzhou HSR,a line with designed speed of 250 km/h (155 mph), averages 207 km/h (129 mph) for the trip. The D312 EMU sleeper train between Beijing South and Shanghai on the non-high speedBeijing–Shanghai railwayaverages 121 km/h (75 mph) for the trip.

- C-class (Thành tế;chéngjì;'intercity') train service that operate on high-speed track at speeds above 250 km/h (155 mph) are also considered high-speed rail service. For example, C-class trains on theBeijing–Tianjin ICR,reach top speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph) and completing the trip in 30 mins.

High-speed ridership statistics in China are often reported as the number of passengers carried by high-speed EMU train sets, and such figures typically include passengers on EMU trains operating on non-high speed track or at service speeds below 200 km/h (124 mph).[15]

History

[edit]

Precursor

[edit]The earliest example of a fast commercial train service in China was theAsia Express,a luxury passenger train that operated in Japanese-controlledManchuriafrom 1934 to 1943.[16]Thesteam-powered train,which ran on theSouth Manchuria RailwayfromDalianto Xinjing (Changchun), had a top commercial speed of 110 km/h (68 mph) and a test speed of 130 km/h (81 mph).[16]It was faster than the fastest trains in Japan at the time. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, this train model was renamed the SL-7 and was used by the Chinese Minister of Railways.

Early planning

[edit]

State planning for China's current high-speed railway network began in the early 1990s under the leadership ofDeng Xiaoping.He set up what became known as the "high-speed rail dream" after his visit to Japan in 1978, where he was deeply impressed by theShinkansen,the world's first high speed rail system.[17]In December 1990, theMinistry of Railways(MOR) submitted to theNational People's Congressa proposal to build a high-speed railway between Beijing and Shanghai.[18]At the time, theBeijing–Shanghai Railwaywas already at capacity, and the proposal was jointly studied by theScience & Technology Commission,State Planning Commission,State Economic & Trade Commission, and the MOR.[18]In December 1994, theState Councilcommissioned a feasibility study for the line.[18]

Policy planners debated the necessity and economic viability of high-speed rail service. Supporters argued that high-speed rail would boost future economic growth. Opponents noted that high-speed rail in other countries were expensive and mostly unprofitable. Overcrowding on existing rail lines, they said, could be solved by expanding capacity through higher speed and frequency of service.[citation needed]In 1995, PremierLi Pengannounced that preparatory work on the Beijing Shanghai HSR would begin in the 9thFive Year Plan(1996–2000), but construction was not scheduled until the first decade of the 21st century.

The "Speed Up" campaigns

[edit]In 1993,commercial train service in Chinaaveraged only 48 km/h (30 mph) and was steadily losing market share toairlineand highway travel on the country's expanding network ofexpressways.[19][20]The MOR focused modernization efforts on increasing the service speed and capacity on existing lines throughdouble-tracking,electrification,improvinggrade(through tunnels and bridges), reducing turn curvature and installingcontinuous welded rail.Through five rounds of"Speed-Up" campaignsin April 1997, October 1998, October 2000, November 2001, and April 2004, passenger service on 7,700 km (4,800 mi) of existing tracks was upgraded to reach sub-high speeds of 160 km/h (100 mph).[21]

A notable example is theGuangzhou–Shenzhen railway,which in December 1994 became the first line in China to offer sub-high-speed service of 160 km/h (99 mph) using domestically produced DF-class diesel locomotives. The line was electrified in 1998, and Swedish-madeX 2000trains increased service speed to 200 km/h (124 mph). After the completion of a third track in 2000 and a fourth in 2007, the line became the first in China to run high-speed passenger and freight service on separate tracks.

The completion of the sixth round of the "Speed-Up" Campaign in April 2007 brought HSR service to more existing lines: 423 km (263 mi) capable of 250 km/h (155 mph) train service and 3,002 km (1,865 mi) capable of 200 km/h (124 mph).[22][note 4]In all, travel speed increased on 22,000 km (14,000 mi), or one-fifth, of the national rail network, and the average speed of passenger trains improved to 70 km/h (43 mph). The introduction of more non-stop service between large cities also helped to reduce travel time. The non-stop express train from Beijing toFuzhoushortened travel time from 33.5 to less than 20 hours.[25] In addition to track and scheduling improvements, the MOR also deployed fasterCRH seriestrains. During the Sixth Railway Speed Up Campaign, 52 CRH trainsets (CRH1,CRH2andCRH5) entered into operation. The new trains reduced travel time between Beijing and Shanghai by two hours to just under 10 hours. Some 295 stations have been built or renovated to allow high-speed trains.[26][27]

The conventional rail v. maglev debate

[edit]The development of the HSR network in China was initially delayed by a debate over the type of track technology to be used. In June 1998, at a State Council meeting with theChinese Academies of SciencesandEngineering,PremierZhu Rongjiasked whether the high-speed railway between Beijing and Shanghai still being planned could usemaglev technology.[28]At the time, planners were divided between using high-speed trains with wheels that run on conventionalstandard gaugetracks or magnetic levitation trains that run on special maglev tracks for a new national high-speed rail network.

Maglev received a big boost in 2000 when theShanghai Municipal Governmentagreed to purchase aturnkeyTransRapidtrain system fromGermanyfor the 30.5 km (19.0 mi) rail link connectingShanghai Pudong International Airportand thecity.In 2004, theShanghai Maglev Trainbecame the world's first commercially operated high-speed maglev. As of 2023[update],it remains the fastest commercial train in the world with peak speeds of 431 km/h (268 mph) and makes the 30.5 km (19.0 mi) trip in less than 7.5 minutes.

Despite unmatched advantage in speed, the maglev has not gained widespread use in China's high-speed rail network due to high cost, German refusal to share technology and concerns about safety. The price tag of the Shanghai Maglev was believed to be $1.3 billion and was partially financed by the German government. The refusal of the Transrapid Consortium to share technology and source production in China made large-scale maglev production much more costly than high-speed train technology for conventional lines. Finally, residents living along the proposed maglev route have raised health concerns about noise andelectromagnetic radiationemitted by the trains, despite an environmental assessment by the Shanghai Academy of Environmental Sciences saying the line was safe.[29]These concerns have prevented the construction of the proposedextension of the maglev to Hangzhou.Even the more modest plan to extend the maglev to Shanghai's other airport,Hongqiao,has stalled. Instead,a conventional subway linewas built to connect the two airports, and aconventional high-speed rail line was built between Shanghai and Hangzhou.

While maglev was drawing attention to Shanghai, conventional track HSR technology was being tested on the newly completedQinhuangdao-Shenyang Passenger Railway.This 405 km (252 mi) standard gauge, dual-track, electrified line was built between 1999 and 2003. In June 2002, a domestically made DJF2 train set a record of 292.8 km/h (181.9 mph) on the track. TheChina Star(DJJ2) train followed the same September with a new record of 321 km/h (199 mph). The line supports commercial train service at speeds of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph), and has become a segment of the rail corridor between Beijing and Northeast China. The Qinhuangdao-Shenyang Line showed the greater compatibility of HSR on conventional track with the rest of China's standard gauge rail network.

In 2004, the State Council in itsMid-to-Long Term Railway Development Plan,adopted conventional track HSR technology over maglev for the Beijing–Shanghai High Speed Railway and three other north–south high-speed rail lines. This decision ended the debate and cleared the way for rapid construction of standard gauge, passenger dedicated HSR lines in China.[30][31]

Acquisition of foreign technology

[edit]Despite setting speed records on test tracks, the DJJ2, DJF2 and other domestically produced high-speed trains were insufficiently reliable for commercial operation.[32]The State Council turned to advanced technology abroad but made clear in directives that China's HSR expansion could not only benefit foreign economies and should also be used to develop its own high-speed train building capacity through technology transfers.[32]The State Council, MOR and state-owned train builders used China's large market and competition among foreign train-makers to force technology transfers of foreign high speed rail technology[citation needed].This would later allow the Chinese government throughCRRCto make the more reliableFu xing HaoandHexie Haotrains. TheCRH380series(or family) of trains was initially built with direct cooperation (or help) from foreign trainmakers, but newer trainsets are based on transferred technology, just like the Hexie and Fu xing Hao.

In 2003, the MOR was believed to favor Japan'sShinkansentechnology, especially the700 series.[32]The Japanese government touted the 40-year track record of the Shinkansen and offered favorable financing. A Japanese report envisioned a winner-take all scenario in which the winning technology provider would supply China's trains for over 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of high-speed rail.[33]However, Chinese citizens angry withJapan's denialof World War II war crimes organized a web campaign to oppose the awarding of HSR contracts to Japanese companies. The protests gathered over a million signatures and politicized the issue.[34]The MOR delayed the decision, broadened the bidding and adopted a diversified approach to adopting foreign high-speed train technology.

In June 2004, the MOR solicited bids to make 200 high-speed train sets that can run 200 km/h (124 mph).[32]Alstomof France,SiemensofGermany,Bombardier Transportationbased in Germany and a Japanese consortium led byKawasakiall submitted bids. With the exception of Siemens which refused to lower its demand ofCN¥350 million per train set and €390 million for the technology transfer, the other three were all awarded portions of the contract.[32]All had to adapt their HSR train-sets to China's own common standard and assemble units through localjoint ventures(JV) or cooperate with Chinese manufacturers. Bombardier, through its joint venture with CSR'sSifang Locomotive and Rolling Stock Co (CSR Sifang),Bombardier Sifang (Qingdao) Transportation Ltd (BST) won an order for 40 eight-car train sets based on Bombardier'sReginadesign.[35]These trains, designatedCRH1A, were delivered in 2006. Kawasaki won an order for 60 train sets based on itsE2 Series Shinkansenfor ¥9.3 billion.[36]Of the 60 train sets, three were directly delivered fromNagoya,Japan, six were kits assembled atCSR Sifang Locomotive & Rolling Stock,and the remaining 51 were made in China using transferred technology with domestic and imported parts.[37]They are known asCRH2A. Alstom also won an order for 60 train sets based on theNew Pendolinodeveloped by Alstom-Ferroviariain Italy. The order had a similar delivery structure with three shipped directly fromSaviglianoalong with six kits assembled by CNR'sCRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles,and the rest locally made with transferred technology and some imported parts.[38]Trains with Alstom technology carry theCRH5designation.

The following year, Siemens reshuffled its bidding team, lowered prices, joined the bidding for 350 km/h (217 mph) trains and won a 60-train set order.[32]It supplied the technology for theCRH3C, based on theICE3 (class 403)design, to CNR'sTangshan Railway Vehicle Co. Ltd.The transferred technology includes assembly, body, bogie, traction current transforming, traction transformers, traction motors, traction control, brake systems, and train control networks.

Technology transfer

[edit]Acquiring high-speed rail technology had been a major goal of Chinese state planners. Chinese train-makers, after receiving transferred foreign technology, have been able to achieve a degree of self-sufficiency in making the next generation of high-speed trains by producing key parts and improving upon foreign designs.

Examples of technology transfer includeMitsubishi Electric’s MT205 traction motor and ATM9 transformer toCSR Zhuzhou Electric,Hitachi’s YJ92A traction motor and Alstom’s YJ87A Traction motor toCNR Yongji Electric,Siemens’ TSG series pantograph toZhuzhou Gofront Electric.Most of the components of the CRH trains manufactured by Chinese companies were from local suppliers, with only a few parts imported.[citation needed]

For foreign train-makers, technology transfer was an important part of gaining market access in China. Bombardier, the first foreign train-maker to form a joint venture in China, has been sharing technology for the manufacture of railway passenger cars and rolling stock since 1998. Zhang Jianwei, President of Bombardier China, stated that in a 2009 interview, “Whatever technology Bombardier has, whatever the China market needs, there is no need to ask. Bombardier transfers advanced andmature technologyto China, which we do not treat as an experimental market.”[39]Unlike other series which have imported prototypes, all CRH1 trains have been assembled at Bombardier's joint-venture with CSR, Bombardier Sifang inQingdao.

Kawasaki's cooperation withCSRdid not last as long. Within two years of cooperation with Kawasaki to produce 60 CRH2A sets, CSR began in 2008 to build CRH2B, CRH2C and CRH2E models at its Sifang plant independently without assistance from Kawasaki.[40]According to CSR president Zhang Chenghong, CSR "made the bold move of forming a systemic development platform for high-speed locomotives and further upgrading its design and manufacturing technology. Later, we began to independently develop high-speed CRH trains with a maximum velocity of 300–350 kilometers per hour, which eventually rolled off the production line in December 2007."[41]Since then, CSR has ended its cooperation with Kawasaki.[42]Kawasaki challenged China's high-speed rail project for patent theft, but backed off the effort.[43]

Between June and September 2005, theMORlaunched bidding for high-speed trains with a top speed of 350 km/h (217 mph), as most of the main high-speed rail lines were designed for top speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph) or higher. Along with CRH3C, produced by Siemens and CNR Tangshan, CSR Sifang bid 60 sets of CRH2C.

In 2007, travel time from Beijing to Shanghai was about 10 hours at a top speed of 200 km/h (124 mph) on the upgradedBeijing–Shanghai Railway.To increase transport capacity, the MOR ordered 70 16-car trainsets from CSR Sifang and BST, including 10 sets of CRH1B and 20 sets of CRH2B seating trains, 20 sets of CRH1E and 20 sets ofCRH2Esleeper trains.

Construction of thehigh-speed railway between Beijing and Shanghai,the world's first high-speed rail with a designed speed of 380 km/h (236 mph), began on April 18, 2008. In the same year, theMinistry of Scienceand the MOR agreed to a joint action plan for the indigenous innovation of high-speed trains in China. The MOR then launched the CRH1-350 (Bombardier and BST, designated asCRH380D), CRH2-350 (CSR,designated asCRH380A/AL), and CRH3-350 (CNRand Siemens, designated asCRH380B/BL&CRH380CL), to develop a new generation of CRH trains with a top operation speed of 380 km/h (236 mph). A total of 400 new generation trains were ordered. TheCRH380A/AL,the first indigenous high-speed train of the CRH series, entered service on theShanghai-Hangzhou High-Speed Railwayon October 26, 2010.[44]

On October 19, 2010, the MOR announced the beginning of research and development of "super-speed" railway technology, which would increase the maximum speed of trains to over 500 km/h (311 mph).[45]

Early passenger-dedicated high-speed rail lines

[edit]After committing to conventional-track high-speed rail in 2006, the state embarked on an ambitious campaign to build passenger-dedicated high-speed rail lines, which accounted for a large part of the government's growing budget for rail construction. Total investment in new rail lines grew from $14 billion in 2004 to $22.7 and $26.2 billion in 2006 and 2007.[46]In response to theglobal economic recession,the government accelerated the pace of HSR expansion to stimulate economic growth. Total investments in new rail lines including HSR reached $49.4 billion in 2008 and $88 billion in 2009.[46]In all, the state planned to spend $300 billion to build a 25,000 km (16,000 mi) HSR network by 2020.[47][48]

As of 2007, theQinhuangdao-Shenyang high-speed railway,which carried trains at top speed of 250 km/h (155 mph) along the Liaoxi Corridor in theNortheast,was the only passenger-dedicated HSR line (PDL) in China, but that would soon change as the country embarked on a high-speed railway construction boom.

National high-speed rail grid (4+4)

[edit]Higher-speed express train service allowed more trains to share the tracks and improved rail transport capacity. But high-speed trains often have to share tracks with slower, heavy freight trains – in some cases with as little as 5 minutes headway.[25]To attain higher speeds and transport capacity, planners began to propose a passenger-dedicated HSR network on a grand scale. Initiated by MOR's 2004 "Mid-to-Long Term Railway Network Plan", a national grid composed of eight high-speed rail corridors, four running north–south and four going east–west, was to be constructed.[49]The envisioned network, together with upgraded existing lines, would total 12,000 km (7,456 mi) in length. Most of the new lines follow the routes of existing trunk lines and are designated for passenger travel only. They became known as passenger-designated lines (PDLs). Several sections of the national grid, especially along the southeast coastal corridor, were built to link cities that had no previous rail connections. Those sections will carry a mix of passenger and freight. High-speed trains on PDLs can generally reach 300–350 km/h (190–220 mph). On mixed-use HSR lines, passenger train service can attain peak speeds of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph). The earliest PDLs built were sections of the corridors that connected large cities in the same region. On April 19, 2008,Hefei–Nanjing PDLin theEastopened with a top-speed of 250 km/h (155 mph). On August 1, 2008, theBeijing–Tianjin intercity railwayopened in time for the2008 Summer Olympics.This line betweennorthern China'stwo largest cities, was the first in the country to accommodate commercial trains with top speed of 350 km/h (217 mph) and featured theCRH2C andCRH3C train sets. This ambitious national grid project was planned to be built by 2020, but the government's stimulus has expedited time-tables considerably for many of the lines.

TheWuhan–Guangzhou high-speed railway (Wuguang PDL),which opened on December 26, 2009, was the country's first cross-regional high-speed rail line. With a total length of 968 km (601 mi) and capacity to accommodate trains traveling at 350 km/h (217 mph), the Wuguang PDL set a world record for the fastest commercial train service with average trip speed of 312.5 km/h (194.2 mph). Train travel betweencentral and southern China’s largest cities, Wuhan and Guangzhou, was reduced to just over three hours. On October 26, 2010, China opened its 15th high-speed rail, theShanghai–Hangzhou line,and unveiled theCRH380Atrainset manufactured by CSR Sifang started regular service. TheBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railway,the second major cross-regional line, opened in June 2011 and was the first line designed with a top speed of 380 km/h (236 mph) in commercial service.[50][51]

By January 2011, China had the world'slongest[broken anchor]high-speed rail network with about 8,358 km (5,193 mi)[52]of routes capable for at least 200 km/h (124 mph) running in service including 2,197 km (1,365 mi) of rail lines with top speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph).[dead link][53]The MOR reportedly committed investment of ¥709.1 billion (US$107.9 billion) in railway construction in 2010 and would invest ¥700 billion (US$106 billion) in 2011 on 70 railway projects, including 15 high-speed rail projects. Some 4,715 kilometres (2,930 mi) of new high-speed railways would be opened, and by the end of 2011, China would have 13,073 kilometres (8,123 mi) of railways capable of carrying trains at speeds of at least 200 km/h (124 mph).[54]

Corruption and concerns

[edit]

In February 2011,Railway MinisterLiu Zhijun,a key proponent of HSR expansion in China, was removed from office on charges of corruption.The Economistestimates Liu accepted¥1 billion of bribes ($152 million) in connection with railway construction projects.[55]Investigators found evidence that another¥187 million ($28.5 million) was misappropriated from the $33 billionBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railwayin 2010.[56] Another top official in the Railways Ministry,Zhang Shuguang,was also sacked for corruption.[55]Zhang was estimated to have misappropriated to his personal overseas accounts the equivalent of $2.8 billion.[57]

After the political shake-up, concerns about HSR safety, high ticket prices, financial sustainability and environmental impact received greater scrutiny in the Chinese press.[58][59]

In April 2011, the new Minister of RailwaysSheng Guangzusaid that due to corruption, safety may have been compromised on some construction projects and completion dates may have to be pushed back.[55]Sheng announced that all trains in the high-speed rail network would operate at a maximum speed of 300 km/h (186 mph) beginning on July 1, 2011.[58][60][61]This was in response to concerns over safety, low ridership due to high ticket prices,[62]and high energy usage.[59]On June 13, 2011, the MOR clarified in a press conference that the speed reduction was not due to safety concerns but to offer more affordable tickets for trains at 250 km/h (155 mph) and increase ridership. Higher-speed train travel uses greater energy and imposes more wear on expensive machinery. Railway officials lowered the top speed of trains on most lines that were running at 350 km/h (217 mph) to 300 km/h (186 mph). Trains on the Beijing-Tianjin high-speed line and a few other inter-city lines remained at 350 km/h (217 mph).[63] In May 2011, China'sEnvironmental Protection Ministryordered the halting of construction and operation of two high-speed lines that failed to pass environmental impact tests.[64][65]In June, the MOR maintained that high-speed rail construction was not slowing down.[66]TheCRH380Atrainsets on theBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railwaycould reach a top operational speed of 380 km/h (240 mph) but were limited to 300 km/h (186 mph).[50][67] Under political and public pressure, theNational Audit Office(NAO) carried out an extensive investigation into the building quality of all high-speed rail lines. As of March 2011, no major quality defects had been found in the system.[68]Foreign manufacturers involved in Shanghai-Beijing high-speed link reported that their contracts call for maximum operational speed of 300 km/h (186 mph).[69]From July 20, 2011, the frequency of train service from Jinan to Beijing and Tianjin was reduced due to low occupancy, which renewed concerns about demand and profitability for high-speed services. Service failures in the first month of operation drove passengers back to pre-existing slower rail service and air travel; airline ticket prices rebounded due to reduced competition.[70]

Wenzhou accident

[edit]

On July 23, 2011, two high-speed trains collided on theNingbo–Taizhou–Wenzhou railwayinLucheng DistrictofWenzhou,Zhe gian gProvince.[71][72][73]The accident occurred when one train traveling near Wenzhou was struck by lightning, lost power and stalled. Signals malfunctioned, causing another train to rear-end the stalled train.[72][74][75][76][77]Several carriagesderailed.[78]State-run Chinese media confirmed 40 deaths, and at least 192 people hospitalised, including 12 who were severely injured.[79][80][81]The Wenzhou train accident and the lack of accountability by railway officials caused a public uproar and heightened concerns about the safety and management of China's high-speed rail system.[82][83]Quality and safety concerns also affected plans to export cheaper high-speed train technology to other countries.[84]

The train collision exposed poor management by the railway company.[85][86]This fatal accident, which happened in the midst of corruption investigations into railway officials, led to greater scrutiny in the Chinese press and the populace concerning the HSR[58][59][85][86]and on the railway company.[58][59]

Following the deadly crash, the Chinese government suspended new railway project approvals and launched safety checks on existing equipment.[87][88]A commission was formed to investigate the accident with a directive to report its findings in September 2011.[89]On August 10, 2011, the Chinese government announced that it was suspending approvals of any new high-speed rail lines pending the outcome of the investigation.[90][91]The Minister of Railways announced further cuts in the speed of Chinese high-speed trains, with the speed of the second-tier 'D' trains reduced from 250 km/h (155 mph) to 200 km/h (124 mph), and 200 km/h (124 mph) to 160 km/h (99 mph) on upgraded pre-existing lines.[92]The speed of the remaining 350 km/h (217 mph) trains between Shanghai and Hangzhou was reduced to 300 km/h (186 mph) as of August 28, 2011.[93]To stimulate ridership, on August 16, 2011, ticket prices on high-speed trains were reduced by five percent.[94]From July to September, high-speed rail ridership in China fell by nearly 151 million trips to 30 million trips.[95]

Slowdown in financing and construction

[edit]

In the first half of 2011, the MOR as a whole made a profit of ¥4.29 billion and carried a total debt burden of ¥2.09 trillion, equal to about 5% of China's GDP.[96][97]Earnings from the more profitable freight lines helped to off-set losses by high-speed rail lines.[citation needed]As of years ending 2008, 2009 and 2010, the MOR's debt-to-asset ratio was respectively, 46.81%, 53.06% and 57.44%,[98]and reached 58.58% by mid-year 2011.[99]As of October 12, 2011, the MOR had issued ¥160 billion of debt for the year.[97]But in the late summer, state banks began to cut back on lending to rail construction projects, which reduced funding for existing railway projects. An investigation of 23 railway construction companies in August 2011 revealed that 70% of existing projects had been slowed or halted mainly due to shortage of funding.[99]Affected lines includedXiamen-Shenzhen,Nanning-Guangzhou, Guiyang-Guangzhou, Shijiazhuang-Wuhan, Tianjin-Baoding and Shanghai-Kunming high-speed rail lines.[95][96]By October, work had halted on the construction of 10,000 km (6,200 mi) of track.[95]New projects were put on hold and completion dates for existing projects, including the Tianjin-Baoding, Harbin-Jiamusi, Zhengzhou-Xuzhou and Hainan Ring (West), were pushed back.[99]As of October 2011, the MOR was reportedly concentrating remaining resources on fewer high-speed rail lines and shifting emphasis to more economically viable coal transporting heavy rail.[97]

To ease the credit shortage facing rail construction, the Ministry of Finance announced tax cuts to interest earned on rail construction financing bonds and the State Council ordered state banks to renew lending to rail projects.[95]In late October and November 2011, the MOR raised RMB 250 billion in fresh financing and construction resumed on several lines including the Tianjin-Baoding, Xiamen-Shenzhen and Shanghai-Kunming.[100]

Recovery

[edit]

By early 2012, the Chinese government renewed investments in high-speed rail to rejuvenate the slowing economy.[103]Premier Wen Jiabao visited train manufacturers and gave a vote of confidence in the industry.[103]Over the course of the year, the MOR's budget rose from $64.3 billion to $96.5 billion.[103]Five new lines totaling 2,563 km (1,593 mi) in length entered operation between June 30 and December 31, including the Beijing-Wuhan section of theBeijing-Guangzhou line.[104]By the end of 2012, the total length of high-speed rail tracks had reached 9,300 km (5,800 mi), and ridership rebounded and exceeded levels prior to the Wenzhou crash.[105][106]China's 1,580 high-speed trains were transporting 1.33 million passengers daily, about 25.7% of the overall passenger traffic.[104]The Beijing–Tianjin, Shanghai–Nanjing, Beijing–Shanghai and Shanghai–Hangzhou lines reported breaking even financially[107][108][109][110]The Shanghai-Nanjing line even reported to be operationally profitable,[109]operating with a 380 million yuan net profit.[108][109]However, in 2013, only few lines had yet become profitable.[110]

On December 28, 2013, the total length of high-speed rail tracks nationally topped 10,000 km (6,200 mi) with the opening of theXiamen–Shenzhen,Xian–Baoji,Chongqing−Lichuanhigh-speed railways as well as intercity lines inHubeiandGuangxi.[111]

Second boom

[edit]

In 2014, high-speed rail expansion gained speed with the opening of theTaiyuan–Xi'an,Hangzhou–Changsha,Lanzhou-Ürümqi,Guiyang-Guangzhou,Nanning-Guangzhou trunk lines and intercity lines aroundWuhan,Chengdu,[112]Qingdao[113]and Zhengzhou.[113]High-speed passenger rail service expanded to 28provinces and regions.[114]The number of high-speed train sets in operation grew from 1,277 pairs in June to 1,556.5 pairs in December.[114][115]

In response to a slowing economy, central planners approved a slew of new lines includingShangqiu-Hefei-Hangzhou,[116]Zhengzhou-Wanzhou,[117]Lianyungang-Zhen gian g,[118]Linyi-Qufu,[119]Harbin-Mudan gian g,[120]Yinchuan-Xi'an,[116]Datong-Zhangjiakou,[116]and intercity lines in Zhe gian g[121]and Jiangxi.[116]

The government actively promoted the export of high-speed rail technology to countries including Mexico, Thailand, the United Kingdom, India, Russia and Turkey. To better compete with foreign trainmakers, the central authorities arranged for the merger of the country's two main high-speed train-makers,CSRandCNR,intoCRRC.[122]

By 2015, six high speed rail lines, Beijing–Tianjin, Shanghai–Nanjing, Beijing–Shanghai, Shanghai–Hangzhou, Nanjing–Hangzhou and Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong report operational profitability.[123]The Beijing–Shanghai is particularly profitable reporting a 6.6 billion yuan net profit.[124]

In 2016, with the near completion of the National 4+4 grid, a new "Mid-to-Long Term Railway Network" Plan was drafted. The plan envisions a larger 8+8 high speed rail grid serving the nation and expanded intercity lines for regional and commuter services for largemetropolitan areasof China.[125]The proposed completion date for the network is 2030.[126]

Since 2017, with the introduction of theFu xingseries of trains, a number of lines have resumed 350 km/h operations such asBeijing–Shanghai HSR,Beijing–Tianjin ICR,andChengdu–Chongqing ICR.[127]

The HSR network reached 37,900 km (23,500 mi) in total length by the end of 2020.[128]In 2025, the HSR network will reach a total length of 50,000 km and will grow further.[129]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: 2023[130] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Development and social impact

[edit]China's high-speed rail expansion is entirely managed, planned and financed by the Chinese government.

Public interest, safety, and concern

[edit]On one hand, the demand of high-speed rail in China steadily increases over time. In 2012, the average occupancy rate of high-speed rails in China was 57%. This percentage increased to 65%, 69% and 72% in the year of 2013, 2014 and 2015, respectively. As of February 2016, high-speed rails covered nearly 20,000 km (12,427 mi).[131]On the other hand, however, public concerns about the high-speed rail development have been raised from various perspectives.[132]

The safety issue that drew the attention of the public and the government was theWenzhou train collisionwhich happened on July 23, 2011, in which 40 people died, 172 were injured, and 54 related officials blamed and punished.[133]According to a 2014 World Bank report, the incident was attributed to inadequate testing of a new design for signaling equipment, which lacked proper fail-safe features. Outside of this major accident in 2011, Chinese HSR provides "world-class" quality of service and comfort, and carries a large volume of passengers safely.[134]

However overall, Chinese high speed rail has an exemplary safety record[135]: 70 and according toThe New York Times,the Chinese high-speed rail network is "one of the world’s safest transportation systems."[136]As of at least 2024, the Wenzhou crash remains the only serious accident in the massive Chinese HSR network.[135]: 70

Construction costs

[edit]According to a 2019 World Bank report, China was able to have construction costs of its high speed rail to be at an average of $17 million to 21 million dollars per km, which is lower than other countries by a third.Standardizationof the designs and procedures were cited as the key reason for keeping costs down.[137][138][139]

Economic efficiency

[edit]Experts expressed concern of the network's operational efficiency.[140][141]In 2016, Chinese railways carried almost 2 trillionton-kilometersof freight and over 1 billionpassenger-kilometerof passengers, making it one of the world's most intensively used freight and passenger railway networks in the world.[142]However, the rail staffproductivityupon railway trackinfrastructureindex in China is less than 0.05, being the lowest among the countries with significant railway construction.[140]The government also articulated the importance and urgency of assuring the capacity of railway staff, especially their familiarity with telecommunication and signaling testing in the official investigation of the Wenzhou train collision.[143]In addition, it is hard to identify problems in the construction process, given thedistribution resource planningsystem needed for rapid railway building and assembling. Suppliers and manufacturers blame each other for any problem detected in the trial operation, while tracking the construction process to every single detail is an almost impossible job for inspectors.[132]

Policy justifications

[edit]Critics both in China and abroad have questioned the necessity of having an expensive high-speed rail system in a largely developing country, where most workers cannot afford to pay a premium for faster travel.[47][48]The government has justified the expensive undertaking as promoting a number of policy objectives. HSR provides fast, reliable and comfortable means of transporting large numbers of travelers ina densely populated countryover long distances,[144][145]which:

- Improves economicproductivityandcompetitivenessover the long term by increasing the transport capacity of railways and linking labor markets.[48][146]Dedicating passenger transport to high-speed lines frees up older conventional railways to freights, which can now carry more payload at lower speed and is more profitable for railway companies than passengers, whose fares are subsidized.[144]

- Stimulates the economy in the short term as HSR construction creates jobs and drives up demand for construction, steel and cement industries during the economic downturn. Work on theBeijing–Shanghai HSRmobilized 110,000 workers.[46][146][147]

- Facilitates cross-city economic integration and promotes the growth ofsecond-tier cities.[148]The introduction of thehigh-speed railwaysis responsible for 59% of the increase in market potential for thesecondary citiesconnected by bullet trains. (Market potential, a concept used byeconomic geographers,measures "a geographic area's access to markets for inputs and outputs." ) A 10% increase in asecondary city'smarket potential is expected to be associated with a 4.5% increase in its averagereal estateprice.[149]

- Supports energy independence and environmental sustainability.Electric trainsuse less energy to transport people and goods on a per unit basis and can draw power from morediverse sources of energyincludingrenewablesthan automobile and aircraft, which are more reliant onimportedpetroleum.[144]

- Develop an indigenous high-speed rail equipment industry. The expansion into HSR is also developing China into a leading source of high-speed rail building technology.[46]Chinese train-makers have absorbed imported technologies quickly, localized production processes, and even begun to compete with foreign suppliers in theexport market.Six years after receiving Kawasaki's license to produce Shinkansen E2, CSC Sifang can produce the CRH2A without Japanese input, and Kawasaki has ended cooperation with Sifang on high-speed rail.[150]

Profitability and debt

[edit]

One major concern of the high-speed rail network is the high amount of debt incurred. As of 2022, the China State Railway Group has had a debt of around US$900 billion, according toNikkei.[10]Conservative scholars and officials are worried that the indebted high-speed rail is further exacerbated by its unprofitability, operating at a daily loss of US$24 million as of November 2021. While a number of high-speed railways in eastern China have started to be operationally profitable since 2015, the high speed railways in the midwest still operate at a loss.Zhengzhou–Xi'an high-speed railwayis estimated to run 59 trains in 2010 and 125 trains in 2018, yet in 2016 there are merely around 30 trains on operation, causing a 1.4 billion loss. TheGuiyang–Guangzhou high-speed railwayandLanzhou–Xin gian g high-speed railway(where fares do not cover electricity costs) are both suffering from high maintenance cost due to harsh climate conditions and complicated terrain structure.[151]TheBeijing-Shanghai high-speed railwayis one of the few lines that have been profitable, with profits steadily increasing after first breaking even in 2014, and achieving revenue of CNY 29.6 billion and net profit of CNY 12.7 billion in 2017.[citation needed]In an analysis conducted in 2019, only five out of fifteen high speed railway lines with travel speeds reaching 350 kilometers per hour, were able to cover all costs that included both the operating and capital costs.[citation needed]

Construction financing

[edit]China's high-speed rail construction projects are highlycapital intensive.About 40–50% of financing is provided by the national government through lending bystate owned banksandfinancial institutions,another 40% by the bonds issued by the Ministry of Railway (MOR) and the remaining 10–20% by provincial and local governments.[99][144]The MOR, through its financing arm, the China Rail Investment Corp (CRIC), issued an estimated¥1 trillion (US$150 billion in 2010 dollars) in debt to finance HSR construction from 2006 to 2010,[152]including ¥310 billion in the first 10 months of 2010.[153]CRIC has also raised some capital throughequity offerings;in the spring of 2010, CRIC sold a 4.5 percent stake in theBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railwayto theBank of Chinafor ¥6.6 billion and a 4.5 percent stake to the public for ¥6 billion.[152]CRIC retained 56.2 percent ownership on that line. As of 2010, the CRIC-bonds are considered to be relatively safe investments because they are backed by assets (the railways) and implicitly by the government.

| Table:Construction cost of HSR lines in operation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Large construction debt-loads require significant revenues from rider fares, subsidies, and/or other sources of income, such as advertising, to repay. Despite impressive ridership figures, virtually every completed line has incurred losses in its first years of operation. For example, theBeijing–Tianjin intercity railwayin its two full years of operation, delivered over 41 million rides. The line cost ¥20.42 billion to build, and ¥1.8 billion per annum to operate, including ¥0.6 billion in interest payments on its ¥10 billion of loan obligations.[172]The terms of the loans range from 5–10 years at interest rates of 6.3 to 6.8 percent.[172]In its first year of operation from August 1, 2008, to July 31, 2009, the line carried 18.7 million riders and generated ¥1.1 billion in revenues, which resulted in a loss of ¥0.7 billion. In the second year, ridership rose to 22.3 million and revenues improved to ¥1.4 billion, which narrowed losses somewhat to below ¥0.5 billion.[172]To break even, the line must deliver 30 million rides annually.[172]To be able to repay principal, ridership would need to exceed 40 million.[172]In September 2010, daily ridership averaged 69,000 or an annual rate of 25.2 million.[172]In 2013, ridership totaled 25.85 million.[173] The line has a capacity of delivering 100 million rides annually[174]and initial estimated repayment period of 16 years.[172]In 2012, the Beijing–Tianjin Intercity Railway reported that it had broken even, and by 2015 was operating at a profit.[175][176]

TheShijiazhuang-Taiyuan PDLlost ¥0.8 billion in its first year and is set to lose ¥0.9 billion in 2010.[152]The Southeast HSR corridor lost ¥0.377 billion in its first year beginning August 2009.[152]TheZhengzhou-Xian HSRsince opening in February 2010 was expected to generate revenues of ¥0.6 billion in its first full year but must make interest payments of ¥1.1 billion. In the first three quarters of 2012, the line lost ¥1.87 billion.[177]The losses must be covered by the operator, which is usually subsidized by local governments.[174]In December 2014, the Henan provincial government imposed a rule requiring municipal authorities pay 70% of the deficit incurred by Henan's intercity lines with the provincial authorities paying the remainder 30%.[178]

The MOR faces a debt-repayment peak in 2014.[152]Some economists recommend further subsidies to lower fares and boost ridership and ultimately revenues.[174]Others warn that the financing side of the existing construction and operation model is unsustainable.[174]If the rail-backed loans cannot be fully repaid, they may be refinanced or the banks may seize ownership of the railways.[152]To prevent that eventuality, the MOR is trying to improve management of its rapidly growing HSR holdings.[152]

Overall, ridership is growing as the high-speed rail network continues to expand. High-speed rail is also becoming relatively more affordable as fares have remained stable while worker wages have grown sharply over the same period.[179]In 2016, the high-speed rail revenue was 140.9 billion RMB Yuan (US$20 billion), while the same term interest from at least 3300 billion debt of its construction was 156.8 billion RMB Yuan (US$22.4 billion).[180]According to theWorld Bank,a stable long term planning and standardization of technology and design used in the high-speed rail helps to reduce financial and operational cost. Standardization of designs and procedures such as train tracks, rolling stocks, signal systems keeps the construction cost down. Moreover, State-owned corporation also usesbulk purchasingto reduce material prices.[181]

Fare cost comparisons

[edit]

In 2013 fares for China's high-speed rail service costs significantly less than similar systems in other developed countries, for comparison high speed rail tickets in France or Germany cost slightly over US$0.10 per kilometer and the various Shinkansen services hover above US$0.20 per kilometer.[citation needed]A 2019 study by theWorld Bank Group,had found that the HSR fares in China are low when compared to other countries and have attracted passengers from all income levels. They noted that HSR is "very competitive" with bus and aircraft transport for distances between 150 km and 800 km (about 3 to 4 hours travel time). Additionally due to the frequency and its high speeds, HSR services that travel at 350kph, still remains competitive with other modes of transport, for distances of up to 1,200 km.[48][182]

| Trip | Distance | Price | Price US$/km | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSR trip fromBeijingtoJinan | 419 km (260 mi) | CNY185 (US$30) | 0.07 | 1 hour 22 minutes |

| HSR trip fromParistoLyon | 428 km (266 mi) | CNY240 (US$39) | 0.10 | 2 hours |

| HSR trip from Madrid to Valencia,Spain | 391 km (243 mi) | €33–58 (US$41–72) | 0.11–0.18 | 1 hour 40 minutes |

| HSR train fromTokyotoGifu-Hashima | 396 km (246 mi) | CNY270 (US$43) | 0.11 | 1 hour 56 minutes |

Impact on airlines

[edit]The spread of high-speed rail has forced domestic airlines in China to slash airfare and cancel regional flights.[183]The impact of high-speed rail on air travel is most acute for intercity trips under 500 km (310 mi).[183]By the spring of 2011, commercial airline service had been completely halted on previously popular routes such as Wuhan–Nanjing, Wuhan–Nanchang, Xi’an–Zhengzhou and Chengdu–Chongqing.[183]Flights on routes over 1,500 km (930 mi) are generally unaffected.[183]As of October 2013, high-speed rail was carrying twice as many passengers each month as the country's airlines.[179]

Track network

[edit]

China's high-speed railway network is by far thelongest in the world.The HSR network reached 45,000 km (28,000 mi) in total length by end of 2023 with plans to reach 70,000 km (43,000 mi) in 2035.[184]HSR lines with design speeds at 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph) are more common than higher speed lines. According to a World Bank publication on Chinese HSR, by the end of 2017 "the length of 300–350 kph lines was about 10,000 km, and the length of 200–250 kph lines was about 15,000 km."[4]

Newer HSR lines are one of three types:

- passenger dedicated lines (PDLs) with a design speed of 350 km/h (217 mph),

- regional lines connecting major cities with a design speed of 250 km/h (155 mph), and

- certain regional "intercity" HSR lines with a design speed of 200–350 km/h (120–220 mph).

Lastly, the HSR network includes rail lines that had been newly constructed during a previous stage of the high speed rail build up, carrying high-speed passenger and express freight trains with a design speed of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph).[4]

National High-Speed Rail Grid

[edit]

The centerpiece of China's expansion into high-speed rail is a national high-speed rail grid consisting of mainly passenger dedicated lines that is overlaid onto the existing railway network.

4+4 HSR Grid

[edit]The grid is composed of eight high-speed rail corridors, four running north–south and four east–west, and has a total of 12,000 km (7,456 mi).[49]Most of the lines follow the routes of existing trunk lines and are designated for passenger traffic only. They are known as passenger-designated lines (PDL). Several sections of the national grid, especially along the southeast coastal corridor, were built to link cities that had no previous rail connections. Those sections will carry a mix of passenger and freight. High-speed trains on HSR Corridors can generally reach 300–350 km/h (190–220 mph). On mixed-use HSR lines, passenger train service can attain peak speeds of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph). This ambitious national grid project was planned to be built by 2020, but the government's stimulus has expedited time-tables considerably for many of the lines.

8+8 HSR Grid

[edit]The 4+4 national HSR grid was largely completed by the end of 2015 and now serves as the backbone of China's HSR network. In July 2016, the state planners reorganized the national HSR network – including HSR lines in operation, under construction and under planning – into eight vertical and eight horizontal high speed rail corridors, almost doubling the network.[185][186]

Eight Verticals[187]

- Coastal corridor

- Beijing–Shanghai corridor

- Beijing–Hong Kong (Taipei) corridor

- Harbin–Hong Kong (Macau) corridor

- Hohhot–Nanning corridor

- Beijing–Kunming corridor

- Baotou (Yinchuan)–Hainan corridor

- Lanzhou (Xining)–Guangzhou corridor

Eight Horizontals[188]

Regional High-Speed Rail

[edit]According to the "Mid-to-Long Term Railway Network Plan" (revised in 2008), the MOR plans to build over 40,000 km (25,000 mi) of railway in order to expand the railway network in western China and to fill gaps in the networks of eastern and central China. Some of these new railways are being built to accommodate speeds of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph) for both passengers and freight. These are also considered high-speed rail though they are not part of the national HSR grid or Intercity High Speed Rail. Several HSR lines planned and built as a regional high-speed railway under the 2008 Revisions have since been incorporated into the 8+8 national grid.

High-speed intercity railways

[edit]Intercity railways are designed to provide regional high-speed rail service between large cities andmetropolitan areasthat are generally within the same province. They are built with the approval of the central government but are financed and operated largely by local governments with limited investment and oversight from the China Rail Corporation. Some intercity lines run parallel to other high-speed rail lines but serve more stations along the route. Intercity HSR service speeds range from 200–350 km/h (120–220 mph).

Passenger-freight railways and connecting conventional lines

[edit]The HSR network includes new mixed passenger-freight lines with a design speed of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph). Some high speed trains also continue on or run over connecting segments of upgraded conventional lines. Trains can operate at 200 km/h (124 mph) on many of the conventional main lines.[4]

Service

[edit]

Rail operators

[edit]China Railway High-speed (CRH)is the major high-speed rail service provided by state-owned railway manufacturing and construction corporationChina Railway.The CRH's high-speed trains are calledHarmonyandRejuvenation.In October 2010, CRH service more than 1,000 trains per day, with a daily ridership of about 925,000.[189]

Almost all HSR trains, tracks, and services are owned and operated by theChina Railway Corporationunder the brandChina Railway High-speed(CRH) with two exceptions being theShanghai Maglev Train,which is operated by theShentong Metro Group,andGuangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link(XRL), which is partially operated by the Hong Kong-basedMTR Corporation.Although both classified as high-speed rail, the Shanghai Maglev often is not counted as part of the national high-speed rail network, while XRL is fully integrated into the national network of the CRH.

China has the world's only commercial maglev high-speed train line in operation. TheShanghai Maglev Train,aturnkeyTransrapidmaglevdemonstration line 30.5 km (19.0 mi) long. The trains have a top operational speed of 430 km/h (267 mph) and can reach a top non-commercial speed of 501 km/h (311 mph). It opened for operations in March 2004, and transports passengers between Shanghai'sLongyang Road stationandShanghai Pudong International Airport.There have been numerous attempts to extend the line without success. AShanghai-Hangzhou maglev linewas also initially discussed but later shelved in favour of conventional high-speed rail.[190]

Two other Maglev lines, theChangsha Maglevand theLine S1of Beijing, were designed for commercial operations with speeds lower than 120 km/h (75 mph).[191]TheFenghuang Maglev[192]opened in 2022 while theQingyuan Maglevis under construction.[193]

Ridership

[edit]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source:[104]2008[194]2010[195]2011[196]2014[197][198]2015[199][200]2016[201]2017[202]2018[203]2019[204]2020-2022[205]2023[206] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

China Railwayreports the number of passengers carried by high-speed EMU train sets and this figure is frequently reported as high-speed ridership, even though this figure includes passengers from EMU trains providing sub-high speed service.[207]In 2007,CRHEMU trains running on conventional trackupgraded in the sixth round of the "Speed-up Campaign"carried 61 million passengers, before the country's first high-speed rail line, theBeijing–Tianjin intercity railway,opened in August 2008.

In 2018, China Railway operated 3,970.5 pairs of passenger train service, of which 2,775 pairs were carried by EMU train sets.[207]Of the 3.313 billion passenger-trips delivered by China Railway in 2018, EMU train sets carried 2.001 billion passenger-trips.[207]This EMU passenger figure includes ridership from certain D- and C-class trains that are technically not within the definition of high-speed rail in China, as well as ridership from EMU train sets serving routes on conventional track or routes that combine high-speed track and conventional track.[207]Nevertheless, by any measure, high-speed rail ridership in China has grown rapidly with expansion of the high-speed rail network and EMU service since 2008.

China is the third country, after Japan and France, to have one billion cumulative HSR passengers. In 2018, annual ridership on EMU train sets, which encompasses officially defined high-speed rail service as well as certain sub-high-speed service routes, accounted for about two-thirds of all regional rail trips (not includingurban trains) in China.[207]At the end of 2018, cumulative passengers delivered by EMU trains is reported to be over 9 billion.[207]

Technology

[edit]Rolling stock

[edit]

China Railway High-speed runs differentelectric multiple unittrainsets, the nameHexie Hao(simplified Chinese:Hài hòa hào;traditional Chinese:Hài hòa hào;pinyin:Héxié Hào;lit.'Harmony') is for designs which are imported from other nations and designated CRH-1 through CRH-5 and CRH380A(L), CRH380B(L), and CRH380C(L). CRH trainsets are intended to provide fast and convenient travel between cities. Some of the Hexie Hao train sets are manufactured locally through technology transfer, a key requirement for China. The signalling, track and support structures, control software, and station design are developed domestically with foreign elements as well. By 2010, the truck system as a whole is predominantly Chinese.[208]China currently holds many new patents related to the internal components of these trains, re-designed in China to allow the trains to run at higher speeds than the foreign designs allowed. However, these patents are only valid within China, and as such hold no international power. The weakness on intellectual property of Hexie Hao causes obstruction for China to export its high-speed rail related product, which leads to the development of the completely redesigned train franchise calledFu xing Hao(simplified Chinese:Phục hưng hào;traditional Chinese:Phục hưng hào;pinyin:Fùxīng Hào;lit.'Rejuvenation') that is based on indigenous technologies.[208][209][210][211]

Maglev

[edit]In October 2016 China'sCRRCannounced that it was beginning research and development on a 600 km/h (373 mph)Maglev trainand would build a 5 km (3.1 mi) test track.[212]In June 2020, a trial run was conducted atTongji University.A planned launch of the maglev train was set for 2025.[213]

Track technology

[edit]

Many of the Passenger Designated Lines useballastless tracks,which allow for smoother train rides at high speeds and can withstand heavy use without warping. The ballastless track technology, imported from Germany, carries higher upfront costs but can reduce maintenance costs.[214][215]

Typical application of track technology in China high-speed lines

| Type | Classify | Technology | line |

| CRTSIs | slab track | RTRI, Japan | Hada PDL |

| CRTSIIs | slab track | Max Bögl, Germany | Jingjin ICL |

| CRTSIIIs | slab track | CRCC, China | Chengguan PDL |

| CRTSIIb | ballastless track | Züblin, Germany | Zhengxi PDL |

Technology export

[edit]Chinese train-makers and rail builders have signed agreements to build HSRs inTurkey,Venezuela, Argentina,[216]and Indonesia[217]and are bidding on HSR projects in theUnited States,Russia,Saudi Arabia,Brazil (São Paulo to Rio de Janeiro)and Myanmar, and other countries.[47]They are competing directly with the established European and Japanese manufacturers, and sometimes partnering with them. In Saudi Arabia'sHaramain High Speed Rail Project,Alstom partnered withChina Railway Construction Corp.to win the contract to build phase I of theMeccatoMedinaHSR line, and Siemens has joinedCSRto bid on phase II.[218]China is also competing with Japan, Germany, South Korea, Spain, France and Italy to bid forCalifornia's high-speed rail line project,which would connect San Francisco and Los Angeles.[219]In November 2009, the MOR signed preliminary agreements with the state's high-speed rail authority andGeneral Electric(GE) under which China would license technology, provide financing and furnish up to 20 percent of the parts with the remaining sourced from American suppliers, and final assembly of the rolling stock in the United States.[220]

In January 2014, the China Railway Construction Corporation completed a 30 km (19 mi) section of theAnkara-Istanbul high-speed railwaybetweenEskişehirandİnönüin westernTurkey.[221]

In 2015, China Railway signed up to design a high-speed railway line between the Russian cities ofMoscowandKazan.Russian state-owned railway corporation JSC Russian Railways cooperated with China Railway Group to plan for a 770-kilometer high-speed rail between the two Russian cities. The estimated total cost of the design contract is 20.8 billion rubles ($383 million) for two years.[222]Once the designs are developed, a separate tender will be held for the construction of the rail link, which Russian Railways expects to cost 1.06 trillion rubles ($19.5 billion).[223]

In October 2023, Indonesia launched the first high-speed railway in Southeast Asia, namedWhoosh,connecting Indonesia's capitalJakartaand its economic hubBandung.[224][225][226]As part of China'sBelt and Road Initiative,the project cost $7.3 billion and was primarily funded by Chinese banks. As per the agreement,China Railwayprovided high-speed rail technologies and operational knowledge to Indonesia whileChina Railway Construction Corporation(CRCC) completed the line. The line is operated byKereta Cepat Indonesia China.According to Western analysts, this is the first complete high-speed rail export project offered by China and signifies China's growing geopolitical influence in the region.[227][228][229][230][231]Indonesia and Chinese authorities discussed further plans to extend the railway across theJavaisland.[232][233]

Records

[edit]

Fastest trains in China

[edit]The "fastest" train commercial service can be defined alternatively by a train's top speed or average trip speed.

- The fastest commercial train service measured by peak operational speed is theShanghai Maglev Trainwhich can reach 431 km/h (268 mph). Due to the limited length of the Shanghai Maglev track 30 km (18.6 mi), the maglev train's average trip speed is only 245.5 km/h (152.5 mph). During testing in 2003, the maglev train achieved the Chinese record speed of 501 km/h (311 mph).[234]

- The fastest commercial train service measured by average train speed is the CRH express service on theBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railway,which reaches a top speed of 350 km/h (220 mph) and completes the 1,302 km (809 mi) journey betweenShanghai HongqiaoandBeijing South,with two stops, in 4 hours and 24 min for an average speed of 291.9 km/h (181.4 mph), the fastest train service measured by average trip speed in the world.[235][236][237]

- The fastest timetabled start-to-stop runs between a station pair in the world are trains G17/G39 on theBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railwayaveraging 317.7 km/h (197.4 mph) running non-stop betweenBeijing SouthtoNanjing Southbefore continuing to other destinations.[238]

- The top speed attained by a non-maglev train in China is 487.3 km/h (302.8 mph) by aCRH380BLtrain on theBeijing–Shanghai high-speed railwayduring a testing run on January 10, 2011.[239]

Longest service distance

[edit]The trains G403/404 and G405/406 for theBeijing West(Beijingxi) -Kunming South(Kunmingnan) service (distance 2,760 km (1,710 mi), travel time about 10 1/2 hours), which began service on January 1, 2017, became the longesthigh-speed railservice in the world.[240]It overtook the G529/530 trains for theBeijing West-Beihai(Beihai Railway Station) service (2,697 km (1,676 mi), 15 1/2 hours for southbound train, 15 3/4 hours for northbound train), which had set the previous record on July 1, 2016.[241]

See also

[edit]- China Railway High-speed

- Fastest trains in China

- List of high-speed railway lines

- Rail transport in China

Media related toHigh-speed rail in Chinaat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toHigh-speed rail in Chinaat Wikimedia Commons High-speed rail in Chinatravel guide from Wikivoyage

High-speed rail in Chinatravel guide from Wikivoyage

Notes

[edit]- ^Taiwan High Speed Railis currently not under the jurisdiction of China Railways (CR) nor is it connected with CR's network. However, official CR news reports countTaiwan Areaalong with THSR in the figure.

- ^Sichuan–Tibet railwayis incorporated into the national high-speed rail service with theChina Railway CR200Jhigh-speed train.[7]

- ^Zhuhai Station,which is served by the HSR network, is located parallel to the Mainland-Macau border, serving also as ade factostation for the land-constrained Macau.

- ^According to Xinhua News Agency, the aggregate results of the six “Speed Up Campaigns” were: boosting passenger train speed on 22,000 km (14,000 mi) of tracks to 120 km/h (75 mph), on 14,000 km (8,700 mi) of tracks to 160 km/h (99 mph), on 2,876 km (1,787 mi) of tracks to 200 km/h (124 mph) and on 846 km (526 mi) of tracks to 250 km/h (155 mph).[23]According toChina Daily,however, there were 6,003 km (3,730 mi) of tracks capable of 200 km/h (124 mph) in April 2007.[24]

Further reading

[edit]- Yan, Karl (2023). "Market-creating states: rethinking China's high-speed rail development".Review of International Political Economy.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Length of Beijing-HK rail network same as Equator".thestar.my.Retrieved2022-01-01.

- ^Ma, Yujia ( mã ngọc giai )."New high-speed trains on drawing board- China.org.cn".china.org.cn.Retrieved2017-11-13.

- ^Preston, Robert (3 January 2023)."China opens 4100km of new railway".International Railway Journal.

- ^abcdLawrence, Martha; Bullock, Richard; Liu, Ziming (2019).China's High-Speed Rail Development.Washington, DC: The World Bank. p. 12.ISBN978-1-4648-1425-9.

- ^"Full speed ahead for China's high-speed rail network in 2019".South China Morning Post.2019-01-03.Retrieved2019-06-23.

- ^"China builds the world's longest high-speed rail as a rail stalls in the U.S."finance.yahoo.21 February 2019.Retrieved2019-06-23.

- ^"China-Tibet bullet trains to commence operations before July".Railway Technology.8 March 2021.

- ^"World's Longest Fast Train Line Opens in China".Associated Press. Archived fromthe originalon 29 December 2012.Retrieved26 December2012.

- ^"China's High-Speed Rail, the world's longest high-speed railway network, is now losing $24 million per day with a reported debt of $1.8 trillion".13 November 2021.

- ^ab"China Railway's debt nears $900bn under expansion push".

- ^Gerald Ollivier, Richard Bullock, Ying Jin and Nanyan Zhou, "High-Speed Railways in China: A Look at Traffic" World Bank China Transport Topics No. 11December 2014, accessed 2017-07-17

- ^"China's Experience with High Speed Rail Offers Lessons for Other Countries".World Bank.Retrieved2022-09-20.

- ^"Is the HSR worth it?".MacroPolo.Retrieved2021-01-24.

we estimate that the HSR network confers a net benefit of $378 billion to the Chinese economy and has an annual ROI of 6.5%.

- ^abcMinistry of Railways 2013,Art. 5.

- ^Seeridership sectionfor further details.

- ^abLouise Young.Japan's Total Empire.Berkeley: University of California Press1998. pp. 246–67.

- ^"China's High-Speed Rail Dream"(PDF).

- ^abcKinh hỗ cao tốc đường sắt luận chứng lịch trình đại sự ký(in Chinese).Retrieved2010-10-04.

- ^Cao thiết thời đại.Trung Quốc quốc gia địa lý võng(in Chinese (China)). 2010-04-07. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-19.Retrieved2010-10-05.

- ^By the mid-1990s, average train speed in China was about 60 km/h (37 mph). (Chinese)"China plans five-year leap forward of railway development"Accessed 2006-09-30

- ^Trung Quốc đường sắt bộ sáu lần đại tăng tốc.Sina News(in Chinese (China)).Retrieved2010-10-04.

- ^"(Chinese)".News.cctv.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Trung Quốc cao thiết "Mười một năm" phát triển kỷ thực: Sử hướng tương lai(in Chinese (China)). Xinhua News Agenc y. 2010-09-25. Archived fromthe originalon 2015-01-13.Retrieved2015-05-09.

- ^Dingding, Xin (2007-04-18)."Bullet trains set to join fastest in the world".China Daily.Archived fromthe originalon 2015-09-24.Retrieved2015-05-09– viaHighBeam Research.

- ^ab"International Railway Journal – Rail And Rapid Transit Industry News Worldwide".Archived fromthe originalon August 15, 2007.

- ^MacLeod, Calum (June 1, 2011)."China slows its runaway high-speed rail expansion".USA Today.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Đường sắt bộ quan viên thâm nhập phân tích: Tương lai quốc gia của ta đường sắt bố cục.Trung Quốc kinh tế võng(in Chinese (China)). 2009-01-19. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-01.Retrieved2020-02-08.

- ^(Chinese)[1]Accessed 2010-10-13

- ^"Hundreds protest Shanghai maglev rail extension".Reuters.Jan 12, 2008.Archivedfrom the original on November 13, 2015.RetrievedJuly 1,2017.

- ^"Rail track beats Maglev in Beijing–Shanghai High Speed Railway".People's Daily.2004-01-18.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^"Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Line, China".Railway-technology. 2011-06-15.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^abcdefTrung Quốc thức cao thiết ra đời cùng trưởng thành.Xinhua(in Chinese). March 4, 2010. Archived fromthe originalon May 10, 2010.

- ^Nhật Bản chờ đợi Trung Quốc ' cầu hôn '(in Chinese). 2003-08-06. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-23.Retrieved2010-08-15.

- ^"Violence flares as the Chinese rage at Japan"Guardian2005-04-17

- ^"High speed Train CRH1 – China"BombardierArchived2010-09-19 at theWayback MachineAccessed 2010-08-14

- ^"Kawasaki Wins High-Speed Train Order for China"2004–10ArchivedJune 8, 2008, at theWayback Machine

- ^"How Japan Profits From China's Plans"Forbes2009-10-26

- ^CRH5 hình động xe tổ kỹ càng tỉ mỉ tư liệu.Trung Quốc đường sắt võng(in Chinese). 2009-11-18. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-08.Retrieved2010-08-15.

- ^Bàng ba địch: Dựa cái gì "Thắng ở Trung Quốc" —— sưu tầm bàng ba địch Trung Quốc khu tổng tài kiêm thủ tịch đại biểu trương kiếm vĩ(in Chinese (China)). Worldrailway.cn.Retrieved2011-08-17.[permanent dead link]

- ^"Japan Inc Shoots Itself on the Foot".Financial Times.2010-07-08.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^"Era of" Created in China "".Chinapictorial.cn.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^"China: A future on track".Xinkaishi.typepad. 2010-10-05.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Uông vĩ (2011-07-08)."China denies Japan's rail patent-infringement claims. On 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-07-25".China.org.cn.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^"First Chinese designed HS train breaks cover".International Railway Journal.September 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-08.Retrieved2010-11-03.

- ^"China's 'Super-Speed' Train Hits 500km".2010-10-20. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-10-29.Retrieved2010-11-03.

- ^abcdBradsher, Keith (2010-02-12)."Keith Bradsher," China Sees Growth Engine in a Web of Fast Trains "".The New York Times.China; United States.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^abc"China to Bid on US High-Speed Rail Projects" A.P.March 13, 2010

- ^abcdForsythe, Michael (2009-12-22)."Michael Forsythe" Letter from China: Is China's Economy Speeding Off the Rails? "".The New York Times.China.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^ab2004 năm quốc gia 《 trung trường kỳ đường sắt võng quy hoạch 》 nội dung tóm tắt(in Chinese). 2014-05-27. Archived fromthe originalon 2019-02-28.Retrieved2017-07-16.

- ^ab"China's fastest high speed train 380A rolls off production line"XinhuaArchived2010-05-30 at theWayback Machine2010-05-27

- ^Khi tốc 380 km cao tốc đoàn tàu sang năm 7 nguyệt khởi hành.163(in Chinese (China)). 2010-11-02.

- ^xinhuanet(2011-02-04)."High-speed rail broadens range of options for China's New Year travel".Archived fromthe originalon February 9, 2011.Retrieved2011-02-04.

- ^"Archived copy"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2012-03-15.Retrieved2011-12-10.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^2011 năm Trung Quốc đường sắt đem đầu tư 7000 trăm triệu nguyên _ công ty kênh _ tài tân võng(in Chinese (China)). Business.caing. 2011-01-05.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^abc"Off the rails?".The Economist.2011-03-31.

- ^"China finds 187 mln yuan embezzled from Beijing-Shanghai railway project".News.xinhuanet. 2011-03-23. Archived fromthe originalon November 7, 2012.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Moore, Malcolm (2011-08-01)."Chinese rail crash scandal: 'official steals $2.8 billion'".The Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-01-12.Retrieved2012-04-27.

- ^abcd"China acts on high-speed rail safety fears".Financial Times. 2011-04-14.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^abcd"China Puts Brakes on High-Speed Trains"The Wall Street Journal2011-04-17

- ^"China slows down showcase bullet trains"Bloomberg Businessweek2011-04-17

- ^"World's longest high-speed train to decelerate a bit".People's Daily Online.2011-04-15.

- ^"The Backlash Is Brewing Against Chinese High-Speed Rail: Here's Why It's In Trouble"Business Insider2011-04-17

- ^"Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway to run trials".News.xinhuanet. 2011-05-11. Archived fromthe originalon May 14, 2011.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Kêu đình tân Tần cao thiết cùng Lưu chí quân xuống ngựa không quan hệ.Tề lỗ báo chiều(in Chinese).QQFinance. May 27, 2011. Archived fromthe originalon July 23, 2011.RetrievedJune 14,2011.

- ^Bảo vệ môi trường bộ kêu đình tân Tần đường sắt, keo tế đường sắt hai cao thiết xây dựng vận hành.The Beijing News(in Chinese). Sohu. 2011-05-19.

- ^Yan, Weijue (June 7, 2011)."China not slowing high-speed rail construction".China Daily.Retrieved2020-02-09.

- ^Khi tốc 380 km cao tốc đoàn tàu sang năm 7 nguyệt khởi hành.163.2010-11-02.

- ^Kinh hỗ cao thiết 2010 năm thẩm kế chưa phát hiện trọng đại chất lượng vấn đề.Sina Finance(in Chinese (China)). 2011-03-23.

- ^"Train speed claims were false".

- ^"Railway cuts bullet trains from schedule | Sunday Digest".China Daily.2011-07-23.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Johnson, Ian (2011-07-24)."Train Wreck in China Heightens Unease on Safety Standards".The New York Times.

- ^abWatt, Louise (2011-07-25)."Crash raises doubts about China's fast rail plans".Washington Times.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^Tania Branigan in Beijing and agencies (2011-08-12)."Chinese bullet trains recalled in wake of fatal crash | World news".The Guardian.UK.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^Lafraniere, Sharon (2011-07-28)."Five Days Later, Chinese Concede Design Flaw Had Role in Wreck".The New York Times.

- ^Reinoso, Jose (2011-07-29)."Un error en las señales causó el choque de trenes chinos".El País Archivo(in Spanish).Retrieved2015-10-17.

- ^"La signalisation mise en cause dans l'accident du Pékin-Shanghaď".Le Monde(in French). France.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^"La sécurité des TGV chinois de plus en plus contestée".Le Monde(in French). France.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^"First fatal crash on Chinese high speed line".Railway Gazette International.

- ^Martin Patience (2011-07-28)."China train crash: Signal design flaw blamed".BBC.co.uk.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^Cherry Wilson (2011-07-23)."China train crash kills 32 The Observer".Guardian.UK.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Martin Patience (2011-07-28)."China train crash: Signal design flaw blamed".BBC.Retrieved2011-08-14.

- ^Coonan, Clifford (2011-08-12)."Outrage at Wenzhou disaster pushes China to suspend bullet train project".The Independent.London.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^"China's High-Speed Rail Accident 'Struck a Nerve' | The Rundown News Blog".PBS NewsHour. 2011-08-10. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-08-12.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^Pilling, David (2011-08-03)."China crashes into a middle class revolt".FT.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^ab"'Design flaws' caused China crash ".2011-12-28.Retrieved2019-07-01.

- ^ab"How China's Train Tragedy Unfolded".The Wall Street Journal.Associated Press. 29 December 2011.

- ^"China steps up train safety amid anger after cras".The Guardian.UK. 2011-08-10.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^"China freezes new railway projects after high-speed train crash".Reuters. 2011-08-10.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-08-17.Retrieved2011-10-17.

- ^"China train crash: Design flaws to blame – safety chief".BBC. 2011-08-12.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^Rabinovitch, Simon (2011-08-11)."China suspends new high speed rail plans".FT.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^"China freezes new railway projects after high-speed train crash".Reuters. 2011-08-10.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-08-17.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^"Decision to slow trains met with mixed response|Nation|chinadaily.cn".chinadaily.cn.

- ^"More high-speed trains slow down to improve safety|Society|chinadaily.cn".chinadaily.cn.

- ^"CapitalVue News: China Cuts Ticket Price Of High Speed Rail".Capitalvue. 2011-08-12. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-03-23.Retrieved2011-08-17.

- ^abcdRabinovitch, Simon (2011-10-27)."China's high-speed rail plans falter".China: Financial Times.Retrieved2011-10-27.