Hiking

Hikingis a long, vigorouswalk,usually ontrailsorfootpathsin the countryside. Walking for pleasure developed in Europe during the eighteenth century.[1]Religiouspilgrimageshave existed much longer but they involve walking long distances for a spiritual purpose associated with specific religions.

"Hiking" is the preferred term inCanadaand theUnited States;the term "walking"is used in these regions for shorter, particularly urban walks. In the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, the word" walking "describes all forms of walking, whether it is a walk in the park orbackpackingin theAlps.The word hiking is also often used in the UK, along withrambling,hillwalking,andfell walking(a term mostly used for hillwalking in northern England). The termbushwalkingis endemic to Australia, having been adopted by the Sydney Bush Walkers club in 1927.[2]In New Zealand a long, vigorous walk or hike is calledtramping.[3]It is a popular activity with numeroushiking organizationsworldwide, and studies suggest that all forms of walking have health benefits.[4][5]

Related terms

[edit]

In the United States, Canada, the Republic of Ireland, and the United Kingdom, hiking means walking outdoors on a trail, or off trail, for recreational purposes.[6]A day hike refers to a hike that can be completed in a single day. However, in the United Kingdom, the word walking is also used, as well as rambling, while walking in mountainous areas is calledhillwalking.InNorthern England,Including theLake DistrictandYorkshire Dales,fell walking describes hill or mountain walks, asfellis the common word for both features there.

Hiking sometimes involves bushwhacking and is sometimes referred to as such. This specifically refers to difficult walking through dense forest, undergrowth, or bushes where forward progress requires pushing vegetation aside. In extreme cases of bushwhacking, where the vegetation is so dense that human passage is impeded, amacheteis used to clear a pathway. The Australian term bushwalking refers to both on and off-trail hiking.[7]Common terms for hiking used by New Zealanders aretramping(particularly for overnight and longer trips),[8]walking or bushwalking.Trekkingis the preferred word used to describe multi-day hiking in the mountainous regions of India, Pakistan, Nepal, North America, South America, Iran, and the highlands ofEast Africa.Hiking along-distance trailfrom end-to-end is also referred to as trekking and asthru-hikingin some places.[9]In North America, multi-day hikes, usually withcamping,are referred to asbackpacking.[6]

History

[edit]

The poetPetrarchis frequently mentioned as an early example of someone hiking. Petrarch recounts that on April 26, 1336, with his brother and two servants, he climbed to the top ofMont Ventoux(1,912 meters (6,273 ft), a feat which he undertook for recreation rather than necessity.[10]The exploit is described in a celebrated letter addressed to his friend and confessor, the monkDionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro,composed some time after the fact. However, some have suggested that Petrarch's climb was fictional.[11][12]

Jakob Burckhardt,inThe Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy(in German in 1860) declared Petrarch "a truly modern man", because of the significance of nature for his "receptive spirit"; even if he did not yet have the skill to describe nature.[13]Petrarch's implication that he was the first to climb mountains for pleasure, and Burckhardt's insistence on Petrarch's sensitivity to nature have been often repeated since. There are also numerous references to Petrarch as an "alpinist",[14]althoughMont Ventouxis not a hard climb, and is not usually considered part of the Alps.[15]This implicit claim of Petrarch and Burckhardt, that Petrarch was the first to climb a mountain for pleasure since antiquity, was disproven byLynn Thorndikein 1943.[16]: 69–74 Mount Ventoux was climbed byJean Buridan,on his way to the papal court inAvignonbefore the year 1334, "in order to make some meteorological observations".[17][18]There were ascents accomplished during theMiddle Ages;[19][16]: 69–74 Lynn Thorndike mentions that "a book on feeling for nature in Germany in the tenth and eleventh centuries, noted various ascents and descriptions of mountains from that period", and that "in the closing years of his life archbishopAnno II, Archbishop of Cologne(c. 1010 – 1075) climbed his beloved mountain oftener than usual ".[16]: 71–72

Other early examples of individuals hiking or climbing mountains for pleasure include the Roman Emperor, Hadrian, who ascended Mount Etna during a return trip from Greece in 125 CE. In 1275, Peter III of Aragon claimed to have reached the summit of Pic du Canigou, a 9134-foot mountain located near the southern tip of France. The first ascent of any technical difficulty to be officially verified took place on June 26, 1492, when Antoine de Ville, a chamberlain and military engineer for Charles VIII, King of France, was ordered to ascend Mont Aiguille. Because ropes, ladders and iron hooks were used during the ascent, this event is widely recognized as being the birth of mountaineering. Conrad Gessner, a 16th Century physician, botanist and naturalist from Switzerland, is widely recognized as being the first person to hike and climb for sheer pleasure.[20]

However, the idea of taking a walk in the countryside only really developed during the 18th century in Europe, and arose because of changing attitudes to the landscape and nature associated with theRomantic movement.[21]In earlier times walking generally indicated poverty and was also associated with vagrancy.[22]: 83, 297 In previous centuries long walks were undertaken as part of religious pilgrimages and this tradition continues throughout the world.

German-speaking world

[edit]The Swiss scientist and poetAlbrecht von Haller's poemDie Alpen(1732) is an historically important early sign of an awakening appreciation of the mountains, though it is chiefly designed to contrast the simple and idyllic life of the inhabitants of theAlpswith the corrupt and decadent existence of the dwellers in the plains.[23]

Numerous travellers explored Europe on foot in the last third of the 18th century and recorded their experiences. A significant example isJohann Gottfried Seume,who set out on foot fromLeipzigto Sicily in 1801, and returned to Leipzig via Paris after nine months.[24]

United Kingdom

[edit]

Thomas West,a Scottish priest, popularized the idea of walking for pleasure in his guide to the Lake District of 1778. In the introduction he wrote that he aimed

to encourage the taste of visiting the lakes by furnishing the traveller with a Guide; and for that purpose, the writer has here collected and laid before him, all the select stations and points of view, noticed by those authors who have last made the tour of the lakes, verified by his own repeated observations.[25]

To this end he included various 'stations' or viewpoints around the lakes, from which tourists would be encouraged to enjoy the views in terms of their aesthetic qualities.[26]Published in 1778 the book was a major success.[27]

Another famous early exponent of walking for pleasure was the English poetWilliam Wordsworth.In 1790 he embarked on an extended tour of France, Switzerland, and Germany, a journey subsequently recorded in his long autobiographical poemThe Prelude(1850). His famous poemTintern Abbeywas inspired by a visit to theWye Valleymade during awalking tourofWalesin 1798 with his sisterDorothy Wordsworth.Wordsworth's friendColeridgewas another keen walker and in the autumn of 1799, he and Wordsworth undertook a three-week tour of the Lake District.John Keats,who belonged to the next generation ofRomantic poetsbegan, in June 1818, a walking tour of Scotland, Ireland, and the Lake District with his friendCharles Armitage Brown.

More and more people undertook walking tours through the 19th century, of which the most famous is probablyRobert Louis Stevenson's journey through theCévennesin France with a donkey, recorded in hisTravels with a Donkey(1879). Stevenson also published in 1876 his famous essay "Walking Tours". The subgenre oftravel writingproduced many classics in the subsequent 20th century. An early American example of a book that describes an extended walking tour is naturalistJohn Muir'sA Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf(1916), a posthumously published account of a long botanizing walk, undertaken in 1867.

Due toindustrialisationin England, people began to migrate to the cities where living standards were often cramped and unsanitary. They would escape the confines of the city by rambling about in the countryside. However, the land in England, particularly around the urban areas ofManchesterandSheffield,was privately owned andtrespasswas illegal. Rambling clubs soon sprang up in thenorthand began politically campaigning for the legal 'right to roam'. One of the first such clubs was 'Sunday Tramps' founded by Leslie White in 1879. The first national grouping, the Federation of Rambling Clubs, was formed in London in 1905 and was heavily patronized by thepeerage.[28]

Access to Mountainsbills,that would have legislated the public's 'right to roam' across some private land, were periodically presented toParliamentfrom 1884 to 1932 without success. Finally, in 1932, the Rambler's Right Movement organized amass trespassonKinder ScoutinDerbyshire.Despite attempts on the part of the police to prevent the trespass from going ahead, it was successfully achieved due to massive publicity. However, the Mountain Access Bill that was passed in 1939 was opposed by many walkers' organizations, includingThe Ramblers,who felt that it did not sufficiently protect their rights, and it was eventually repealed.[29]

The effort to improve access led after World War II to theNational Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949,and in 1951 to the creation of the firstnational parkin the UK, thePeak District National Park.[30]The establishment of this and similar national parks helped to improve access for all outdoors enthusiasts.[31]TheCountryside and Rights of Way Act 2000considerably extended theright to roamin England and Wales.[32][33]

United States

[edit]

An early example of an interest in hiking in the United States isAbel Crawfordand his son Ethan's clearing of a trail to the summit ofMount Washington, New Hampshirein 1819.[34]This 8.5-mile path is the oldest continually used hiking trail in the United States. The influence of British and EuropeanRomanticismreached North America through thetranscendentalist movement,and bothRalph Waldo Emerson(1803–82) andHenry David Thoreau(1817–62) were important influences on the outdoors movement in North America. Thoreau's writing on nature and on walking include the posthumously published "Walking" (1862) ".[35]His earlier essay "A Walk to Wachusett"(1842) describes a four-daywalking tourThoreau took with a companion from Concord, Massachusetts to the summit ofMount Wachusett,Princeton, Massachusettsand back. Established in 1876, theAppalachian Mountain Clubhas the distinction of being the oldest hiking club in America. It was founded to protect the trails and mountains in the northeastern United States. Prior to its founding, four other hiking clubs had already been established in America. This included the very short-lived (first) Rocky Mountain Club in 1875, the White Mountain Club of Portland in 1873, the Alpine Club of Williamstown in 1863, and the Exploring Circle, which was established by four men from Lynn, Massachusetts in 1850. Although not a hiking club in the same sense as the clubs that would emerge later, the National Park Service recognizes the Exploring Circle as being "the first hiking club in New England."[36]All four of these clubs would disband within a few years of their founding.[20]

Despite clubs such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, hiking during the early twentieth century was still primarily in New England,San Francisco,and the Pacific Northwest. Eventually, there were similar clubs formed in the Midwest and following the Appalachian range. As interest grew hiking culture was spread throughout the nation.[1]

The Scottish-born, American naturalistJohn Muir(1838 –1914), was another important early advocate of the preservation of wilderness in the United States. He petitioned theU.S. Congressfor the National Park bill that was passed in 1890, establishing Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. TheSierra Club,which he founded, is now one of the most important conservation organizations in the United States. The spiritual quality and enthusiasm toward nature expressed in his writings inspired others, including presidents and congressmen, to take action to help preserve large areas of undeveloped countryside.[37]He is today referred to as the "Father of the National Parks".[38]In 1916, the National Park Service was created to protect national parks and monuments.[39][40][41]

In 1921,Benton MacKaye,a forester, conceived the idea of what would become America's first National Scenic Trail, theAppalachian trail(AT). The AT was completed in August 1937, running from Maine to Georgia. ThePacific Crest Trail( "PCT" ) was first explored in the 1930s by theYMCAhiking groups and was eventually registered as a complete border to border trail from Mexico to Canada.[42]

Pilgrimages

[edit]Pilgrimageroutes are now treated by some walkers as long-distance routes, and the route taken by the BritishNational TrailtheNorth Downs Wayclosely follows that of thePilgrims' WaytoCanterbury.[43]

The ancient pilgrimage, theCamino de Santiago,or Way of St. James, has become more recently the source for a number of long-distance hiking routes. This is a network ofpilgrims' waysleading to the shrine of theapostleSaint James the Greatin thecathedral of Santiago de CompostelainGaliciain northwestern Spain. Many follow its routes as a form of spiritual path or retreat for their spiritual growth.

TheFrench Wayis the most popular of the routes and runs fromSaint-Jean-Pied-de-Porton the French side of thePyreneestoRoncesvalleson the Spanish side and then another 780 kilometres (480 mi) on to Santiago de Compostela through the major cities ofPamplona,Logroño,BurgosandLeón.A typical walk on theCamino francéstakes at least four weeks, allowing for one or two rest days on the way. Some travel the Camino on bicycle or on horseback. Paths from the cities ofTours,Vézelay,andLe Puy-en-Velaymeet at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.[44]The French long-distance pathGR 65(of theGrande Randonnéenetwork), is an important variant route of the oldChristianpilgrimageway.

TheAbraham Pathis a cultural route believed to have been the path ofIslamic,Christian,andJewishpatriarchAbraham's ancient journey across theAncient Near East.[45]The path was established in 2007 as a pilgrimage route betweenUrfa, Turkey,possibly his birthplace, and his final destination of the desert ofNegev.

Destinations

[edit]

National parksare often important hiking destinations, such asNational Parks of England and Wales;of Canada;of New Zealand,of South Africa,etc.

Frequently, nowadays long-distance hikes (walking tours) are undertaken along long-distance paths, including theNational Trailsin England and Wales, theKungsleden(Sweden) and theNational Trail Systemin the United States. TheGrande Randonnée(France), Grote Routepaden, or Lange-afstand-wandelpaden (The Netherlands), Grande Rota (Portugal), Gran Recorrido (Spain) is a network oflong-distance footpathsin Europe, mostly in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain. There are extensive networks in other European countries of long-distance trails, as well as in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Nepal, and to a lesser extent other Asiatic countries, like Turkey, Israel, and Jordan. In the Alps of Austria, Slovenia, Switzerland, Germany, France, and Italy walking tours can be made from 'hut-to-hut', using an extensive system ofmountain huts.

In the late 20th-century, there has been a proliferation of official and unofficial long-distance routes, which mean that hikers now are more likely to refer to using a long-distance way (Britain), trail (US),The Grande Randonnée(France), etc., than setting out on a walking tour. Early examples of long-distance paths include theAppalachian Trailin the US and thePennine Wayin Britain.

Organized hiking clubs emerged in Europe at approximately the same time as official hiking trails. These clubs established and upheld their own paths during the 19th and 20th centuries, prioritizing the development of extended hiking routes. In 1938, the first long-distance hiking trail in Europe, the Hungarian National Blue Trail, was established in the Hungarian wilderness, stretching approximately 62 miles (100 km).

Asia

[edit]

In the Middle East, theJordan Trailis a 650 km (400 miles) long hiking trail in Jordan established in 2015 by the Jordan Trail Association. AndIsraelhas been described as "a trekker's paradise" with over 9,656 km (6,000 miles) of trails.[46]

TheLycian Wayis a markedlong-distance trailin southwestern Turkey around part of the coast of ancientLycia.[47]It is over 500 km (310 mi) in length and stretches fromHisarönü(Ovacık), nearFethiye,toGeyikbayırıinKonyaaltıabout 20 km (12 mi) fromAntalya.It was conceived by Briton Kate Clow, who lives in Turkey. It takes its name from the ancient civilization, which once ruled the area.[47]

TheGreat Himalaya Trailis a route across theHimalayas.The original concept of the trail was to establish a single long distance trekking trail from the east end to the west end ofNepalthat includes a total of roughly 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) of path. The proposed trail will link together a range of the less explored tourism destinations of Nepal's mountain region.[48]

Latin America

[edit]InLatin America,PeruandChileare important hiking destinations. TheInca Trail to Machu Picchuin Peru is very popular and apermit is required.The longest hiking trail in Chile is the informal 3,000 km (1,850 mi)Greater Patagonia Trailthat was created by a non-governmental initiative.[49]

Africa

[edit]In Africa a majortrekkingdestination[50]isMount Kilimanjaro,adormantvolcanoinTanzania,which is the highestmountain in Africaand the highest single free-standing mountain in the world: 5,895 metres (19,341 ft) above sea level and about 4,900 metres (16,100 ft) above its plateau base.[51]

Equipment

[edit]

The equipment required for hiking depends on a variety of factors, including local climate. Day hikers often carry water, food, a map, hat, and rain-proof gear.[6]Hikers have traditionally worn sturdyhiking boots[6]for stability over rough terrain. In recent decades this has become less common as somelong-distance hikershave switched totrail running shoes.[52]Boots are still commonly used in mountainous terrain.The Mountaineersclub recommends a list of "Ten Essentials"equipment for hiking, including a compass, sunglasses, sunscreen, aflashlight,a first aid kit, afire starter,and a knife.[53]Other groups recommend items such as hat, gloves, insect repellent, and anemergency blanket.[54]AGPS navigation devicecan also be helpful androute cardsmay be used as a guide.Trekking polesare also recommended, especially when carrying a heavy backpack.[55]Winter hiking requires a higher level of skill and generally more specialized gear than in other seasons (see winter hiking below).

Proponents ofultralight backpackingargue that long lists of required items for multi-day hikes increases pack weight, and hence fatigue and the chance of injury.[56]Instead, they recommend reducing pack weight, to make hiking long distances easier. Even the use of hiking boots on long-distances hikes is controversial among ultralight hikers, because of their weight.[56]

Hiking times can be estimated byNaismith's ruleorTobler's hiking function,while distances can be measured on a map with anopisometer.Apedometeris a device that records the distance walked.

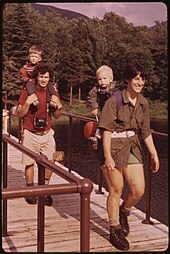

Hiking with children

[edit]

TheAmerican Hiking Societyadvises that parents with young children should encourage them to participate in decision-making about route-finding and pace.[57]Alisha McDarris, writing inPopular Science,suggests that, whilst hiking with children poses particular challenges, it can be a rewarding experience for them, particularly if a route is chosen with their interests in mind.[58]

Young children are prone to becoming fatigued more rapidly than adults, requiring fluids and energy-rich foods more frequently, and are also more sensitive to variations in weather and terrain. Hiking routes may be chosen with these factors in mind, and appropriate clothing, equipment and sun-protection need to be available.[59][60]

Environmental impact

[edit]

Natural environmentsare often fragile and may be accidentally damaged, especially when a large number of hikers are involved. For example, years of gathering wood can strip an alpine area of valuable nutrients, and can cause deforestation;[61]and some species, such asmartensorBighorn Sheep,are very sensitive to the presence of humans, especially around mating season. Generally, protected areas such as parks have regulations in place to protect the environment, so as to minimize such impact.[61]Such regulations include banning wood fires, restrictingcampingto established campsites, disposing or packing outfaecal matter,and imposing a quota on the number of hikers. Many hikers espouse the philosophy ofLeave No Trace,following strict practices on dealing withfood waste,food packaging, and other impacts on the environment.[62] Human feces are often a major source of environmental impact from hiking,[61]and can contaminate the watershed and make other hikers ill. 'Catholes' dug 10 to 25 cm (4 to 10 inches) deep, depending on local soil composition and covered after use, at least 60 m (200 feet) away from water sources and trails, are recommended to reduce the risk of bacterial contamination.

Fire is a particular source of danger, and an individual hiker can have a large impact on an ecosystem. For example, in 2005, a Czech backpacker accidentally started a fire that burnt 5% ofTorres del Paine National Parkin Chile.[63]

Etiquette

[edit]Because hikers may come into conflict with other users of the land or may harm the natural environment, hiking etiquette has developed.

- When two groups of hikers meet on a steep trail, a custom has developed in some areas whereby the group moving uphill has theright-of-way.[64]

- Various organizations recommend that hikers generally avoid making loud sounds, such as shouting or loud conversation, playing music, or the use of mobile phones.[64]However, in bear country, hikers use intentional noise-making as a safety precaution to avoid startling bears.

- TheLeave No Tracemovement offers a set of guidelines for low-impact hiking: "Leave nothing but footprints. Take nothing but photos. Kill nothing but time. Keep nothing but memories".[65]

- Hikers are advised not to feed wild animals, because they will become a danger to other hikers if they become habituated to human food, and may have to be killed, or relocated.[66]

Hazards

[edit]

Hiking can be hazardousbecause of terrain, inclement weather, becoming lost, or pre-existing medical conditions. The dangerous[67]circumstances hikers can face include specific accidents or physical ailments. It is especially hazardous in high mountains, crossing rivers and glaciers, and when there is snow and ice. At times hiking may involvescrambling,as well as the use of ropes, ice axes and crampons and the skill to properly use them.

Potential hazards involving physical ailments may include dehydration, frostbite, hypothermia, sunburn, sunstroke, ordiarrhea,[68]and such injuries as ankle sprains, or broken bones.[69]Hypothermiais a danger for all hikers and especially inexperienced hikers. Weather does not need to be very cold to be dangerous since ordinary rain or mist has a strong cooling effect. In high mountains a further danger isaltitude sickness.This typically occurs only above 2,500 metres (8,000 ft), though some are affected at lower altitudes.[70][71]Risk factors include a prior episode of altitude sickness, a high degree of activity, and a rapid increase in elevation.[70]

Other threats include attacks by animals (e.g., bears, snakes, andinsectsortickscarryingdiseasessuch asLyme) or contact with noxious plants that can cause rashes (e.g.,poison ivy,poison oak,poison sumac,orstinging nettles). Lightning is also a threat, especially on high ground.

Walkers in high mountains, and during winter in many countries, can encounter hazardous snow and ice conditions, and the possibility ofavalanches.[72]Year roundglaciersare potentially hazardous.[73]Fast flowing water presents another danger and a safe crossing may requires special techniques.[74]

In various countries, borders may be poorly marked. In 2009, Iran imprisoned three Americans for hiking across the Iran-Iraq border.[75]It is illegal to cross into the US on thePacific Crest Trailfrom Canada. Going south to north it is more straightforward and a crossing can be made, if advanced arrangements are made withCanada Border Services.Within theSchengen Area,which includes most of theE.U.,and associated nations like Switzerland and Norway, there are no impediments to crossing by path, and borders are not always obvious.[76]

Winter hiking

[edit]

Hiking in winter offers additional opportunities, challenges and hazards.Cramponsmay be needed in icy conditions, and anice axis recommended on steep, snow covered paths.Snowshoesandhiking poles,orcross country skisare useful aid for those hiking in deep snow.[77] An example of a close relationship between skiing and hiking is found in Norway, where TheNorwegian Trekking Associationmaintains over 400 huts stretching across thousands of kilometres of trails which hikers can use in the summer and skiers in the winter.[78]For longer routes in snowy conditions, hikers may resort toski touring,using specialised skis and boots for uphill travel.[79]In winter, factors such as shortened daylight, changeable weather conditions and avalanche risk can raise the hazard level of hiking.[80][81]

See also

[edit]Types

[edit]- Backpacking (hiking).And, in winter,Ski touring

- Dog hiking– hiking where a dog carries a pack

- Fastpacking– fast hiking with light gear

- Glacier hiking– hiking on a glacier that has affinities tomountaineering

- Llama hiking– hiking where llamas accompany people

- Nordic Walking– fitness walking withtrekking poles

- Swimhiking– a sport that combines hiking and swimming

- Ultralight backpacking– carrying the least amount of gear necessary

- Waterfalling– hiking that explores waterfalls

Related activities

[edit]- Cross-country skiing– hiking snow with the aid of skis

- Fell running– the sport of running over rough mountainous ground, often off-trail

- Geocaching– an outdoor treasure-hunting game

- Orienteering– a sport that involves navigation with a map and compass

- Peak bagging– ticking-off a list of mountain peaks climbed

- Pilgrimage– a journey of moral or spiritual significance

- River trekking– a combination of trekking and climbing and sometimes swimming along a river

- Rogaining– a sport of long-distance cross-country navigation

- Snow shoeing– walking across deep snow on snow shoes

- Thru-hiking– hiking an established long-distance hiking trail continuously in one direction

- Trail blazing– using signages to mark a hiking route (known as way-marking in Europe)

- Trail running– running on trails

References

[edit]- ^abAmato, Joseph A. (2004).On Foot: A History of Walking.NYU Press. pp. 101–24.ISBN978-0-8147-0502-5.JSTORj.ctt9qg056.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-05-18.Retrieved2020-11-25.

- ^"Sydney Bush Walkers Club's history".Archivedfrom the original on 2017-02-22.Retrieved2017-02-21.

- ^Orsman, HW (1999).The Dictionary of New Zealand English.Auckland: Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-558347-7.

- ^McKinney, John (2009-03-22)."For Good Health: Take a Hike!".Miller-McCune.Archived fromthe originalon 2011-04-29.

- ^"A Step in the Right Direction: The health benefits of hiking and trails"(PDF).American Hiking Society. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 September 2011.Retrieved1 June2012.

- ^abcdKeller, Kristin T. (2007).Hiking.Capstone Press.ISBN978-0-7368-0916-0.

- ^"Bushwalking Australia home".Bushwalking Australia.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-03-22.Retrieved2016-03-18.

- ^Orsman, HW (1999).The Dictionary of New Zealand English.Auckland: Oxford University Press.ISBN9780195583472.

- ^Mueser, Roland (1997).Long-Distance Hiking: Lessons from the Appalachian Trail.McGraw-Hill.ISBN0-07-044458-7.

- ^Nicolson, Marjorie Hope.Mountain Gloom and Mountain Hlory; The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite.W.W. Norton & Co., Inc. [1963, c1959]. p. 49.OCLC1031245016.

- ^Cassirer, Ernst (January 1943). "Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance".Journal of the History of Ideas.4(1).University of Pennsylvania Press:49–74.doi:10.2307/2707236.JSTOR2707236.

- ^Halsall, Paul (August 1998)."Petrarch: The Ascent of Mount Ventoux".fordham.edu.Fordham University.Archivedfrom the original on 8 January 2014.Retrieved5 March2014.

- ^"Civilization,Part IV §3, beginning ".Archived fromthe originalon February 3, 2007.

- ^Cassirer, Ernst; Kristeller, Paul Oskar; Randall, John Herman (1956).The Renaissance Philosophy of Man.University of Chicago Press. p. 28.doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226149790.001.0001.ISBN978-0-226-09604-9.

- ^Bishop, p.102,104

- ^abcThorndike, Lynn(Jan 1943)."Renaissance or Prenaissance".Journal of the History of Ideas.4(1).JSTOR2707236.JSTORlink to a collection of several letters in the same issue.

- ^Moody, Ernest A."Jean Buridan"(PDF).Dictionary of Scientific Biography.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2021-02-13.Retrieved2020-11-24.

- ^Kimmelman, Michael (1999-06-06)."NOT Because it's There".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-02.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^Burckhardt, Jacob (1904) [1860].The Civilisation of the Period of the Renaissance in Italy.Translated by Middlemore, SGC.Swan Sonnenschein.pp. 301–302.

- ^abDoran, Jeffrey J. (2023).Ramble On: How Hiking Became One of the Most Popular Outdoor Activities in the World.Amazon Digital Services LLC – Kdp.ISBN979-8373963923.

- ^Abrams, MH, ed. (2000).The Norton Anthology of English Literature.Vol. 2 (7th ed.). pp. 9–10.ISBN9780393963380.

- ^Solnit, Rebecca (2000).Wanderlust: A History of Walking.New York: Penguin Books.ISBN0670882097.

- ^Chisholm 1911,p. 855.

- ^Krüger, Arnd (2010). Menzel, Anne; Endress, Martin; Hedorfer, Petra; Antz, Christian (eds.).Wandertourismus: Kundengruppen, Destinationsmarketing, Gesundheitsaspekte.München.ISBN978-3-486-70469-3.OCLC889248430.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^West, Thomas (1780).A Guide to the Lakes.HardPress. p. 2.ISBN9780371947258.

- ^"Development of tourism in the Lake District National Park".Lake District UK. Archived fromthe originalon October 11, 2008.Retrieved2008-11-27.

- ^"Understanding the National Park — Viewing Stations".Lake District National Park Authority. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-01-04.Retrieved2008-11-27.

- ^Stephenson, Tom (1989).Forbidden Land: The Struggle for Access to Mountain and Moorland.Manchester University Press. p.78.ISBN9780719028915.Retrieved2013-02-07.

- ^Stephenson, T.; Holt, A.; Harding, M. (1989). "The 1939 Access to Mountains Act".Forbidden Land: The Struggle for Access to Mountain and Moorland.Manchester University Press. p.165.ISBN978-0-7190-2966-0.

- ^"Quarrying and mineral extraction in the Peak District National Park"(PDF).Peak District National Park Authority. 2011. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 27 January 2012.Retrieved17 April2012.

- ^"Kinder Trespass. A history of rambling".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-08.Retrieved2013-12-17.

- ^"Open access land: management, rights and responsibilities".GOV.UK.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-10.Retrieved2021-03-09.

- ^"Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000".legislation.gov.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-24.Retrieved2023-05-09.

- ^Condensed Facts About Mount Washington.Atkinson News Co. 1912.

- ^Thoreau, Henry David."Walking".The Atlantic.No. June 1862.Archivedfrom the original on 13 October 2017.Retrieved24 July2017.

- ^"Lynn Woods Historic District".NPS.7 July 2020.Retrieved28 May2023.

- ^"The Life and Contributions of John Muir".Sierra Club. Archived fromthe originalon March 31, 2014.RetrievedOctober 23,2009.

- ^Miller, Barbara Kiely (2008).John Muir.Gareth Stevens. p. 10.ISBN978-0836883183.

- ^"Quick History of the National Park Service (U.S. National Park Service)".nps.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-09.Retrieved2021-03-09.

- ^"National Park Service".HISTORY.21 August 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-05.Retrieved2021-03-09.

- ^"Congress Creates the National Park Service".National Archives.2016-08-25.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-26.Retrieved2021-03-09.

- ^"The Top 10 Hiking Trails in the US".e2e. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-02-23.Retrieved2014-02-12.

- ^"North Downs Way National Trail | Paths by name | Ramblers, Britain's Walking Charity".2012-07-28. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-28.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^Starkie, Walter(1965) [1957].The Roads to Santiago: Pilgrims of St. James.University of California Press.

- ^"Abraham Path | a cultural route connecting the storied places associated with Abraham's ancient journey".abrahampath.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-05-17.Retrieved2017-05-16.

- ^"Hiking in Israel – a trekkers paradise".2012-08-15. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-05-25.

- ^ab"Lycian Way".Culture Routes Society.Retrieved2024-06-16.

- ^"Great Himalaya Trails:: Trekking, hiking and walking in Nepal".Great Himalaya Trails.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-11-16.Retrieved2020-11-14.

- ^Dudeck, Jan."Greater Patagonian Trail".Wikiexplora.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2014.Retrieved1 September2014.

- ^Trimble, Morgan (2016-11-15)."How to climb Kilimanjaro without the crowds".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-02.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^Sharaf, Yasir (24 March 2016)."Mount Kilimanjaro Volcanic Cones: Shira, Kibo And Mawenzi Peaks".XPATS International.Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2021.Retrieved7 December2021.

- ^O'Grady, Kyle (4 December 2015)."The Footwear Debate: Are Trail Runners Superior to Boots?".The Trek.Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2020.Retrieved28 July2020.

- ^Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills(6th ed.). The Mountaineers. 1997. pp. 35–40.ISBN0-89886-427-5.

- ^"Ten Essential Groups Article".Texas Sierra Club. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-06-02.Retrieved2011-01-19.

- ^"Trekking Poles".American Hiking Association. 10 April 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-11-13.Retrieved2020-11-13.

- ^abJardine, Ray (2000).Beyond Backpacking: Ray Jardine's Guide to Lightweight Hiking.AdventureLore Press.ISBN0963235931.

- ^Ray, Tyler (2013-04-10)."Hiking with Kids".American Hiking Society.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-02-03.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^McDarris, Alisha (2020-05-19)."What you need to know when hiking with kids".Popular Science.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-11-27.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^"Wandern mit Kindern".alpenverein.at(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 27 January 2021.Retrieved27 December2020.

- ^Bloch, Romana (Sep 2017)."Bergtouren mit Kindern: Das muss man beachten!"[Mountain tours with children: You have to pay attention to this!].Alpin(in German).Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2020.Retrieved27 December2020.

- ^abcCole, David."Impacts of Hiking and Camping on Soils and Vegetation: A Review"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2010-07-06.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^"About Our Mission".Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-09-16.Retrieved2020-09-19.

- ^"Chile and Czech Republic work to restore Torres del Paine Park".MercoPress.2009-09-30.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-06-17.Retrieved2020-06-17.

- ^abDevaughn, Melissa (April 1997)."Trail Etiquette".Backpacker Magazine.Active Interest Media, Inc. p. 40.ISSN0277-867X.Retrieved22 January2011.

- ^"Leave No Trace Seven Principles (U.S. National Park Service)".nps.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-18.Retrieved2021-03-18.

- ^"Do Not Feed Wildlife".Upper Thames River Conservation Authority.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-02.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^"Is Hiking Dangerous?".Trekkearth.17 December 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 18 December 2021.Retrieved18 December2021.

- ^Boulware, D.R.; et al. (2003). "Medical Risks of Wilderness Hiking".American Journal of Medicine.114(4): 288–93.doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01494-8.PMID12681456.

- ^Goldenberg, Marni; Martin, Bruce (2007).Hiking and Backpacking.Wilderness Education Association. p. 104.ISBN978-0-7360-6801-7.

- ^ab"Altitude Diseases – Injuries; Poisoning".Merck Manuals Professional Edition.May 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 27 June 2018.Retrieved3 August2018.

- ^Simancas-Racines, D; Arevalo-Rodriguez, I; Osorio, D; Franco, JV; Xu, Y; Hidalgo, R (30 June 2018)."Interventions for treating acute high altitude illness".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.6(12): CD009567.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009567.pub2.PMC6513207.PMID29959871.

- ^"Avalanche danger".Pacific Crest Trails Association.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-11-12.Retrieved2020-11-13.

- ^"How to cross a glacier".Washington Trails Association.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-12.Retrieved2020-11-13.

- ^"Stream crossing safety while hiking and backpacking".Pacific Crest Trail Association.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-11-08.Retrieved2020-11-12.

- ^Gordon, Michael R.; Lehren, Andrew W. (2010-10-23)."Iran Seized U.S. Hikers in Iraq, U.S. Report Asserts".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-04-24.Retrieved2017-02-24.

- ^"Hiking the Via Alpina – Questions / Answers".via-alpina.org.Archivedfrom the original on August 5, 2020.RetrievedMay 31,2020.

- ^"Winter Hiking: What to Know Before You Go".Appalachian Trail Conservancy.2019-01-21.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-31.Retrieved2023-01-02.

- ^Volken, Martin; Schnell, Scott; Wheeler, Margaret (2007).Backcountry Skiing: Skills for Ski Touring and Ski Mountaineering.Mountaineers Books. p.12.ISBN978-1-59485-038-7.Retrieved2014-07-12.

- ^"Transport in, to and out of the backcountry – Snow Safety information".mountainacademy.salomon.Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2020.Retrieved21 November2020.

- ^"Ten mistakes winter walkers make – and how to avoid them".thebmc.co.uk.British Mountaineering Council.Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2020.Retrieved21 November2020.

- ^"Hill skills: avalanche awareness".thebmc.co.uk.British Mountaineering Council.Archivedfrom the original on 27 November 2020.Retrieved21 November2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Amata, Joseph (2004).On Foot, A History of Walking.New York: New York University Press.ISBN9780814705025.See summary of contents

- Berger, Karen(2017).Great Hiking Trails of the World.New York: Rizzoli.ISBN978-0-847-86093-7.

- Chamberlin, Silas (2016).On the Trail: A History of American Hiking.Yale University Press.

- Doran, Jeffrey J. (2023).Ramble On: How Hiking Became One of the Most Popular Outdoor Activities in the World.Amazon Digital Services LLC – Kdp.ISBN979-8373963923.

- Gros, Frédéric (2014).A Philosophy of Walking.Translated by Howe, John. London, New York: Verso.ISBN9781781682708.

- Solnit, Rebecca (2000).Wanderlust: a history of walking.New York: Viking.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Haller, Albrecht von".Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.