History of Germany

This articlemay betoo longto read and navigate comfortably.When this tag was added, itsreadable prose sizewas 26,000 words.(May 2023) |

This articlecontains too many pictures for its overall length. |

| History ofGermany |

|---|

|

The concept ofGermanyas a distinct region inCentral Europecan be traced toJulius Caesar,who referred to the unconquered area east of theRhineasGermania,thus distinguishing it fromGaul.The victory of theGermanic tribesin theBattle of the Teutoburg Forest(AD9) prevented annexation by theRoman Empire,although theRoman provincesofGermania SuperiorandGermania Inferiorwere established along theRhine.Following theFall of the Western Roman Empire,theFranksconquered the otherWestGermanic tribes.When theFrankish Empirewas divided amongCharles the Great's heirs in 843, the eastern part becameEast Francia.In 962,Otto Ibecame the firstHoly Roman Emperorof theHoly Roman Empire,the medieval German state.

During theHigh Middle Ages,theHanseatic League,dominated by German port cities, established itself along theBalticandNorth Seas.The growth of a crusading element within GermanChristendomled to theState of the Teutonic Orderalong the Baltic coast in what would later becomePrussia.In theInvestiture Controversy,the German Emperors resisted Catholic Church authority. In theLate Middle Ages,the regional dukes, princes, and bishops gained power at the expense of the emperors.Martin Lutherled theProtestant Reformationwithin the Catholic Church after 1517, as the northern and eastern states became Protestant, while most of the southern and western states remained Catholic. TheThirty Years' War,a civil war from 1618 to 1648 brought tremendous destruction to the Holy Roman Empire. The estates of the empire attained great autonomy in thePeace of Westphalia,the most important beingAustria,Prussia,BavariaandSaxony.With theNapoleonic Wars,feudalism fell away and the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806.Napoleonestablished theConfederation of the Rhineas a German puppet state, but after the French defeat, theGerman Confederationwas established under Austrian presidency. TheGerman revolutions of 1848–1849failed but theIndustrial Revolutionmodernized the German economy, leading to rapid urban growth and the emergence of thesocialist movement.Prussia, with its capitalBerlin,grew in power. German universities became world-class centers for science and humanities, while music and art flourished. Theunification of Germanywas achieved under the leadership of the ChancellorOtto von Bismarckwith the formation of theGerman Empirein 1871. The newReichstag,an elected parliament, had only a limited role in the imperial government. Germany joined the other powers incolonial expansion in Africa and the Pacific.

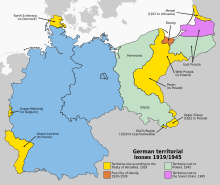

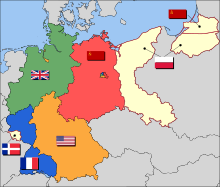

By 1900, Germany was the dominant power on the European continent and its rapidly expanding industry had surpassedBritain's while provoking it ina naval arms race.Germany led theCentral PowersinWorld War I,but was defeated, partly occupied, forced to paywar reparations,and stripped of its colonies and significant territory along its borders. TheGerman Revolution of 1918–1919ended the German Empire with the abdication ofWilhelm IIin 1918 and established theWeimar Republic,an ultimately unstable parliamentary democracy. In January 1933,Adolf Hitler,leader of theNazi Party,used the economic hardships of theGreat Depressionalong with popular resentment over the terms imposed on Germany at the end of World War I to establish atotalitarianregime. ThisNazi Germanymade racism, especiallyantisemitism,a central tenet of its policies, and became increasingly aggressive with its territorial demands, threatening war if they were not met. Germany quickly remilitarized, annexed its German-speaking neighbors andinvaded Poland,triggeringWorld War II.During the war, the Nazis established a systematicgenocideprogram known asthe Holocaustwhich killed 17 million people, including 6 million Jews (representing 2/3rds of the European Jewish population). By 1944, the German Army was pushed back on all fronts until finally collapsing in May 1945. Underoccupation by the Allies,denazificationefforts took place, large populations under former German-occupied territories were displaced, German territories were split up by the victorious powers and in the east annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union. Germany spent the entirety of theCold Warera divided into theNATO-alignedWest GermanyandWarsaw Pact-alignedEast Germany.Germans also fled from Communist areas into West Germany, which experienced rapideconomic expansion,and became the dominant economy in Western Europe.

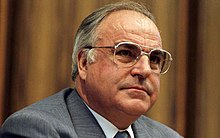

In 1989, theBerlin Wallwasopened,theEastern Bloccollapsed, andEast and West Germany were reunitedin 1990. TheFranco-German friendshipbecame the basis for the political integration of Western Europe in theEuropean Union.In 1998–1999, Germany was one of the founding countries of theeurozone.Germany remains one of the economic powerhouses of Europe, contributing about 1/4 of the eurozone's annualgross domestic product.In the early 2010s, Germany played a critical role in trying to resolve the escalating euro crisis, especially concerning Greece and otherSouthern Europeannations. In 2015, Germany faced theEuropean migrant crisisas the main receiver of asylum seekers fromSyriaand other troubled regions. Germany opposedRussia's 2022 invasion of Ukraineand decided to strengthenits armed forces.

Prehistory

[edit]Paleolithic and Neolithic ages

[edit]Pre-human apes such asDanuvius guggenmosi,who were present in Germany over 11 million years ago, are theorized to be among the earliest apes to walk on two legs prior to other species and genera such asAustralopithecus.[1]The discovery of theHomo heidelbergensismandible in 1907 affirms archaic human presence in Germany by at least 600,000 years ago,[2]so stone tools were dated as far back as 1.33 million years ago.[3]The oldest complete set of hunting weapons ever found anywhere in the world was excavated from a coal mine inSchöningen,Lower Saxony.Between 1994 and 1998,eight 380,000-year-old wooden javelinsbetween 1.82 and 2.25 m (5.97 and 7.38 ft) in length were eventually unearthed.[4][5] One of the oldest buildings in the world and one of the oldest pieces of art was found inBilzingsleben.[6]

In 1856, the fossilized bones of an extinct human species were salvaged from a limestone grotto in theNeandervalley nearDüsseldorf,North Rhine-Westphalia.The archaic nature of the fossils, now known to be around 40,000 years old, was recognized and the characteristics published in the first-everpaleoanthropologicspecies descriptionin 1858 byHermann Schaaffhausen.[7]The species was namedHomo neanderthalensis,Neanderthalman in 1864.

The oldest traces ofhomo sapiensin Germany were found in the caveIlsenhöhleinRanis,where up to 47,500-year-old remains were discovered, among the oldest in Europe.[8]The remains ofPaleolithicearly modern humanoccupation uncovered and documented in several caves in theSwabian Jurainclude various mammoth ivory sculptures that rank among the oldest uncontested works of art and several flutes, made of bird bone and mammoth ivory that are confirmed to be the oldest musical instruments ever found. The 41,000-year-oldLöwenmensch figurinerepresents the oldest uncontested figurative work of art and the 40,000-year-oldVenus of Hohle Felshas been asserted as the oldest uncontested object of human figurative art ever discovered.[9][10][11][12]These artefacts are attributed to theAurignacianculture.

Between 12,900 and 11,700 years ago, north-central Germany was part of theAhrensburg culture(named forAhrensburg).

The first groups of early farmers different from the indigenous hunter-gatherers to migrate into Europe came from a population in westernAnatoliaat the beginning of theNeolithicperiod between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago.[13]

Central Germany was one of the primary areas of theLinear Pottery culture(c. 5500 BC– c. 4500 BC), which was partially contemporary with theErtebølle culture(c. 5300 BC– c. 3950 BC) of Denmark and northern Germany. The construction of the Central EuropeanNeolithic circular enclosuresfalls in this time period with the best known and oldest being theGoseck circle,constructedc. 4900 BC.Afterwards, Germany was part of theRössen culture,Michelsberg cultureandFunnelbeaker culture(c. 4600 BC– c. 2800 BC). The oldest traces for the use of wheel and wagon ever found are located at a northern German Funnelbeaker culture site and date to around 3400 BC.[14]

Bronze Age

[edit]The settlers of theCorded Ware culture(c. 2900 BC– c. 2350 BC), that had spread all over the fertile plains of Central Europe during the Late Neolithic were ofIndo-Europeanancestry. The Indo-Europeans had, via mass-migration, arrived into the heartland of Europe around 4,500 years ago.[16]

By the lateBronze Age,theUrnfield culture(c. 1300 BC– c. 750 BC) had replaced theBell Beaker,UneticeandTumulus culturesin central Europe,[17]whilst theNordic Bronze Agehad developed in Scandinavia and northern Germany. The name comes from the custom ofcrematingthe dead and placing their ashes inurns,which were then buried in fields. The first usage of the name occurred in publications over grave sites in southern Germany in the late 19th century.[18][19]Over much of Europe, the Urnfield culture followed theTumulus cultureand was succeeded by theHallstatt culture.[20]TheItalic peoples,including theLatins,from which theRomansemerged, come from the Urnfield culture of central Europe.[21][22][23]

Iron Age

[edit]TheHallstatt culture,which had developed from the Urnfield culture, was the predominant Western and Central European culture from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and during the earlyIron Age(8th to 6th centuries BC). It was followed by theLa Tène culture(5th to 1st centuries BC).

The people who had adopted these cultural characteristics in central and southern Germany are regarded asCelts.How and if the Celts are related to the Urnfield culture remains disputed. However, Celtic cultural centres developed in central Europe during the late Bronze Age (c. 1200 BCuntil 700 BC). Some, like theHeuneburg,the oldest city north of the Alps,[24]grew to become important cultural centres of the Iron Age in Central Europe, that maintained trade routes to theMediterranean.In the 5th century BC the Greek historianHerodotusmentioned a Celtic city at the Danube –Pyrene,that historians attribute to the Heuneburg. Beginning around 700 BC (or later),Germanic peoples(Germanic tribes) fromsouthern Scandinavia and northern Germanyexpanded south and gradually replaced the Celtic peoples in Central Europe.[25][26][27][28][29][30]

Early history: Germanic tribes, Roman conquests, and the Migration Period

[edit]Early migrations, the Suebi and the Roman Republic

[edit]

Theethnogenesisof theGermanic tribesremains debated. However, for authorAveril Cameron"it is obvious that a steady process" occurred during theNordic Bronze Age,or at the latest during thePre-Roman Iron Age[33](Jastorf culture). From their homes in southern Scandinavia and northern Germany the tribes began expanding south, east and west during the 1st century BC,[34]and came into contact with theCeltictribes ofGaul,as well as withIranic,[35]Baltic,[36]andSlaviccultures inCentral/Eastern Europe.[37]

Factual and detailed knowledge about the early history of the Germanic tribes is rare. Researchers have to be content with the recordings of the tribes' affairs with theRomans,linguistic conclusions, archaeological discoveries and the rather new yet auspicious results ofarchaeogeneticstudy.[38]In the mid-1st century BC,Republican RomanstatesmanJulius Caesarerected thefirst known bridges across the Rhineduring hiscampaign in Gauland led a military contingent across and into the territories of the local Germanic tribes. After several days and having made no contact with Germanic troops (who had retreated inland) Caesar returned to the west of the river.[39]By 60 BC, theSuebitribe under chieftainAriovistus,had conquered lands of the GallicAeduitribe to the west of the Rhine. Consequent plans to populate the region with Germanic settlers from the east were vehemently opposed by Caesar, who had already launched hisambitious campaignto subjugate all Gaul. Julius Caesar defeated the Suebi forces in 58 BC in theBattle of Vosgesand forced Ariovistus to retreat across the Rhine.[40][41]

Roman settlement of the Rhine

[edit]

Augustus,firstRoman emperor,considered conquest beyond theRhineand theDanubenot only regular foreign policy but also necessary to counter Germanic incursions into a still rebellious Gaul. Forts and commercial centers were established along the rivers. Some tribes, such as theUbiiconsequently allied with Rome and readily adopted advanced Roman culture. During the 1st century CE Roman legions conducted extended campaigns intoGermania magna,the area north of the Upper Danube and east of the Rhine, attempting to subdue the various tribes. Roman ideas of administration, the imposition of taxes and a legal framework were frustrated by the total absence of an infrastructure.Germanicus'scampaigns,for example, were almost exclusively characterized by frequent massacres of villagers and indiscriminate pillaging. The tribes, however maintained their elusive identities. A coalition of tribes under theCheruscichieftainArminius,who was familiar with Roman tactical doctrines, defeated a large Roman force in theBattle of the Teutoburg Forest.Consequently, Rome resolved to permanently establish the Rhine/Danube border and refrain from further territorial advance into Germania.[42][43]By AD 100 the frontier along the Rhine and the Danube and theLimes Germanicuswas firmly established. Several Germanic tribes lived under Roman rule south and west of the border, as described inTacitus'sGermania.Austria formed the regular provinces ofNoricumandRaetia.[44][45][46]The provincesGermania Inferior(with the capital situated atColonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium,modernCologne) andGermania Superior(with its capital atMogontiacum,modernMainz), were formally established in 85 AD, after long campaigns as lasting military control was confined to the lands surrounding the rivers.[47]Christianity was introducedto Roman controlled western Germania before the Middle Ages, with Christian religious structures such as theAula PalatinaofTrierbuilt during the reign ofConstantine I(r. 306–337).[48]

Migration Period and decline of the Western Roman Empire

[edit]Rome'sThird Century Crisiscoincided with the emergence of a number of large West Germanic tribes: theAlamanni,Franks,Bavarii,Chatti,Saxons,Frisii,Sicambri,andThuringii.By the 3rd century the Germanic speaking peoples began to migrate beyond thelimesand the Danube frontier.[49]Several large tribes – theVisigoths,Ostrogoths,Vandals,Burgundians,Lombards,SaxonsandFranks– migrated and played their part in thedecline of the Roman Empireand the transformation of the oldWestern Roman Empire.[50]By the end of the 4th century theHunsinvaded eastern and central Europe, establishing theHunnic Empire.The event triggered theMigration Period.[51]Hunnic hegemony over a vast territory in central and eastern Europe lasted until the death ofAttila's sonDengizichin 469.[52]Another pivotal moment in the Migration Period was theCrossing of the Rhinein December of 406 by a large group of tribes includingVandals,AlansandSuebiwho settled permanently within the crumbling Western Roman Empire.[53]

Stem duchies and marches

[edit]

Stem duchies(‹See Tfd›German:Stammesherzogtümer) in Germany refer to the traditional territory of the various Germanic tribes. The concept of such duchies survived especially in the areas which by the 9th century would constituteEast Francia,[54]which included theDuchy of Bavaria,theDuchy of Swabia,theDuchy of Saxony,theDuchy of Franconiaand theDuchy of Thuringia,[55]unlike further west theCounty of BurgundyorLorraineinMiddle Francia.[56] [57]

TheSalian emperors(reigned 1027–1125) retained the stem duchies as the major divisions of Germany, but they became increasingly obsolete during the early high-medieval period under theHohenstaufen,andFrederick Barbarossafinally abolished them in 1180 in favour of more numerous territorial duchies.

Successive kings of Germany founded a series of border counties ormarchesin the east and the north. These includedLusatia,theNorth March(which would becomeBrandenburgand the heart of the futurePrussia), and theBillung March.In the south, the marches includedCarniola,Styria,and theMarch of Austriathat would becomeAustria.

Middle Ages

[edit]Frankish Empire

[edit]The Western Roman Empire fell in 476 with thedeposition of Romulus Augustusby the GermanicfoederatileaderOdoacer,who became the firstKing of Italy.[58]Afterwards, the Franks, like other post-Roman Western Europeans, emerged as a tribal confederacy in the Middle Rhine-Weser region, among the territory soon to be calledAustrasia(the "eastern land" ), the northeastern portion of the future Kingdom of theMerovingianFranks.As a whole, Austrasia comprised parts of present-dayFrance,Germany,Belgium,Luxembourgand theNetherlands.Unlike theAlamannito their south inSwabia,they absorbed large swaths of former Roman territory as they spread west intoGaul,beginning in 250.Clovis Iof theMerovingian dynastyconquered northern Gaul in 486 and in theBattle of Tolbiacin 496 theAlemannitribe inSwabia,which eventually became theDuchy of Swabia.

By 500, Clovis had united all the Frankish tribes, ruled all of Gaul[59]and was proclaimedKing of the Franksbetween 509 and 511.[60]Clovis, unlike most Germanic rulers of the time, was baptized directly intoRoman Catholicisminstead ofArianism.His successors would cooperate closely withpapalmissionaries, among themSaint Boniface.After the death of Clovis in 511, his four sons partitioned his kingdom includingAustrasia.Authority over Austrasia passed back and forth from autonomy to royal subjugation, as successiveMerovingiankings alternately united and subdivided the Frankish lands.[61]

During the 5th and 6th centuries the Merovingian kings conquered theThuringii(531 to 532), theKingdom of the Burgundiansand the principality of Metz and defeated the Danes, the Saxons and the Visigoths.[62]KingChlothar I(558 to 561) ruled the greater part of what is now Germany and undertook military expeditions intoSaxony,while the South-east of what is modern Germany remained under the influence of theOstrogoths.Saxons controlled the area from the northern sea board to theHarz Mountainsand theEichsfeldin the south.[63]

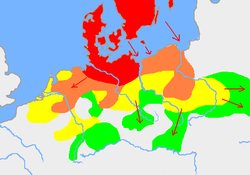

Blue = realm ofPepin the Shortin 758;

Orange = expansion underCharlemagneuntil 814;

Yellow =Marchesand dependencies;

Red =Papal States.

The Merovingians placed the various regions of their Frankish Empire under the control of semi-autonomous dukes – either Franks or local rulers,[64]and followedimperial Romanstrategic traditions of social and political integration of the newly conquered territories.[65][66]While allowed to preserve their own legal systems,[67]the conquered Germanic tribes were pressured to abandon theArianChristian faith.[68]

In 718Charles Martelwaged war against the Saxons in support of theNeustrians.In 743 his sonCarlomanin his role asMayor of the Palacerenewed the war against the Saxons, who had allied with and aided the dukeOdilo of Bavaria.[69]The Catholic Franks, who by 750 controlled avast territoryin Gaul, north-western Germany, Swabia,Burgundyand westernSwitzerland,that included thealpinepasses allied with the Curia inRomeagainst theLombards,who posed a permanent threat to the Holy See.[59]Pressed byLiutprand, King of the Lombards,a Papal envoy for help had already been sent to the de facto rulerCharles Martelafter his victory in 732 over the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate at theBattle of Tours,however a lasting and mutually beneficial alliance would only materialize after Charles' death under his successor Duke of the Franks, Pepin the Short.[70]

In 751Pippin III,Mayor of the Palaceunder the Merovingian king, himself assumed the title of king and was anointed by the Church.Pope Stephen IIbestowed him the hereditary title ofPatricius Romanorumas protector of Rome and St. Peter[71]in response to theDonation of Pepin,that guaranteed the sovereignty of thePapal States.Charles the Great(who ruled the Franks from 774 to 814) launched a decades-long military campaign against the Franks' heathen rivals, theSaxonsand theAvars.The campaigns and insurrections of theSaxon Warslasted from 772 to 804. The Franks eventually overwhelmed the Saxons and Avars, forcibly converted the people toChristianity,and annexed their lands to theCarolingian Empire.

Foundation of the Holy Roman Empire

[edit]

After the death of Frankish kingPepin the Shortin 768, his oldest son "Charlemagne"(" Charles the Great ") consolidated his power over and expanded theKingdom.Charlemagne ended 200 years of Royal Lombard rule with theSiege of Pavia,and in 774 he installed himself asKing of the Lombards.Loyal Frankish nobles replaced the old Lombard aristocracy following a rebellion in 776.[72]The next 30 years of his reign were spent ruthlessly strengthening his power in Francia and on the conquest of the Slavs andPannonian Avarsin the east and alltribes,such as theSaxonsand theBavarians.[73][74]OnChristmas Day,800 AD, Charlemagne was crownedImperator Romanorum(Emperor of the Romans) in Rome byPope Leo III.[74]

Fighting among Charlemagne's three grandsons over the continuation of the custom ofpartible inheritanceor the introduction ofprimogeniturecaused the Carolingian empire to be partitioned into three parts by theTreaty of Verdunof 843.[75]Louis the Germanreceived the Eastern portion of the kingdom,East Francia,all lands east of the Rhine river and to the north of Italy. This encompassed the territories of the Germanstem duchies– Franks, Saxons,Swabians,and Bavarians – that were united in a federation under the first non-Frankish kingHenry the Fowler,who ruled from 919 to 936.[76]The royal court permanently moved in between a series of strongholds, calledKaiserpfalzen,that developed into economic and cultural centers.Aachen Palaceplayed a central role, as the localPalatine Chapelserved as the official site for all royal coronation ceremonies during the entire Medieval period until 1531.[74][77]

-

The division of theCarolingian Empireby theTreaty of Verdunin 843

-

Territorial evolution of theHoly Roman Empirefrom 962 to 1806

-

TheHoly Roman Empireat its greatest territorial extent underHohenstaufenemperorFrederick II,13th century

-

TheHoly Roman Empirearound the year 1700

Otto the Great

[edit]

In 936,Otto Iwas crowned German king atAachen,in 961King of ItalyinPaviaand crowned emperor byPope John XIIinRomein 962. The tradition of the German King as protector of the Kingdom of Italy and the Latin Church resulted in the termHoly Roman Empirein the 12th century. The name, that was to identify with Germany continued to be used officially, with the extension added:Nationis Germanicæ (of the German nation)after the last imperial coronation in Rome in 1452 until its dissolution in 1806.[76]Otto strengthened the royal authority by re-asserting the oldCarolingianrights over ecclesiastical appointments.[78]Otto wrested from the nobles the powers of appointment of the bishops and abbots, who controlled large land holdings. Additionally, Otto revived the old Carolingian program of appointing missionaries in the border lands. Otto continued to supportcelibacyfor the higher clergy, so ecclesiastical appointments never became hereditary. By granting lands to the abbots and bishops he appointed, Otto actually turned these bishops into "princes of the Empire" (Reichsfürsten).[79]In this way, Otto was able to establish a national church. Outside threats to the kingdom were contained with the decisive defeat of the HungarianMagyarsat theBattle of Lechfeldin 955. TheSlavsbetween theElbeand theOderrivers were also subjugated. Otto marched on Rome and droveJohn XIIfrom the papal throne and for years controlled the election of the pope, setting a firm precedent for imperial control of the papacy for years to come.[80][81]

During the reign of Conrad II's son,Henry III(1039 to 1056), the empire supported theCluniac reformsof the Church, thePeace of God,prohibition ofsimony(the purchase of clerical offices), and requiredcelibacyof priests. Imperial authority over the Pope reached its peak. However, Rome reacted with the creation of theCollege of CardinalsandPope Gregory VII'sseries of clerical reforms.Pope Gregory insisted in hisDictatus Papaeon absolute papal authority over appointments to ecclesiastical offices. The subsequent conflict in which emperorHenry IVwas compelled to submit to the Pope atCanossain 1077, after having been excommunicated came to be known as theInvestiture Controversy.In 1122, a temporary reconciliation was reached betweenHenry Vand the Pope with theConcordat of Worms.With the conclusion of the dispute the Roman church and the papacy regained supreme control over all religious affairs.[83][84]Consequently, the imperial Ottonian church system (Reichskirche) declined. It also ended the royal/imperial tradition of appointing selected powerful clerical leaders to counter the Imperial secular princes.[85]

Between 1095 and 1291 the various campaigns of thecrusadesto the Holy Land took place. Knightly religious orders were established, including theKnights Templar,the Knights of St John (Knights Hospitaller), and theTeutonic Order.[86][87]

The termsacrum imperium(Holy Empire) was first used officially byFriedrich Iin 1157,[88]but the wordsSacrum Romanum Imperium,Holy Roman Empire, were only combined in July 1180 and would never consistently appear on official documents from 1254 onwards.[89]

Hanseatic League

[edit]

TheHanseatic Leaguewas a commercial and defensive alliance of the merchantguildsof towns and cities in northern and central Europe that dominated marine trade in theBaltic Sea,theNorth Seaand along the connected navigable rivers during the Late Middle Ages ( 12th to 15th centuries ). Each of the affiliated cities retained the legal system of its sovereign and, with the exception of theFree imperial cities,had only a limited degree of political autonomy.[90]Beginning with an agreement of the cities ofLübeckandHamburg,guilds cooperated in order to strengthen and combine their economic assets, like securing trading routes and tax privileges, to control prices and better protect and market their local commodities. Important centers of commerce within the empire, such asCologneon theRhineriver andBremenon theNorth Seajoined the union, which resulted in greater diplomatic esteem.[91]Recognized by the various regional princes for the great economic potential, favorable charters for, often exclusive, commercial operations were granted.[92]During its zenith the alliance maintained trading posts andkontorsin virtually all cities betweenLondonandEdinburghin the west toNovgorodin the east andBergenin Norway. By the late 14th century the powerful league enforced its interests with military means, if necessary. This culminated ina warwith the sovereign Kingdom of Denmark from 1361 to 1370. Principal city of the Hanseatic League remained Lübeck, where in 1356 the first general diet was held and its official structure was announced. The league declined after 1450 due to a number of factors, such as the15th-century crisis,the territorial lords' shifting policies towards greater commercial control, thesilver crisisand marginalization in the wider Eurasian trade network, among others.[93][94]

Eastward expansion

[edit]

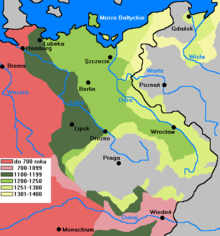

TheOstsiedlung(lit. Eastern settlement) is the term for a process of largely uncoordinated immigration and chartering of settlement structures by ethnic Germans into territories, already inhabited bySlavsandBaltseast of theSaaleandElberivers, such as modern Poland andSilesiaand to the south intoBohemia,modern Hungary and Romania during theHigh Middle Agesfrom the 11th to the 14th century.[95][96]The primary purpose of the early imperial military campaigns into the lands to the east during the 10th and 11th century, was to punish and subjugate the localheathentribes. Conquered territories were mostly lost after the troops had retreated, but eventually were incorporated into the empire asmarches,fortified borderlands with garrisoned troops in strongholds and castles, who were to ensure military control and enforce the exaction of tributes. Contemporary sources do not support the idea of policies or plans for the organized settlement of civilians.[97]

Emperor Lothair IIre-established feudal sovereignty over Poland, Denmark and Bohemia from 1135 and appointedmargravesto turn the borderlands into hereditaryfiefsand install a civilian administration. There is no discernible chronology of the immigration process as it took place in many individual efforts and stages, often even encouraged by the Slavic regional lords. However, the new communities were subjected to German law and customs. Total numbers of settlers were generally rather low and, depending on who held a numerical majority, populations usually assimilated into each other. In many regions only enclaves would persist, likeHermannstadt,founded by theTransylvanian Saxonsin the medieval Hungarian Kingdom (today in Romania) who were called on byGeza IIto repopulate the area as part of theOstsiedlung,having arrived there and founding the city in 1147 [Saxons called these parts of Transylvania "Altland" to distinguish them from later immigrant Saxon settlements established in about 1220 by the Teutonic Order].[98][99]

In 1230, the Catholicmonasticorder of theTeutonic Knightslaunched thePrussian Crusade.The campaign, that was supported by the forces of Polish dukeKonrad I of Masovia,initially intended to Christianize the BalticOld Prussians,succeeded primarily in the conquest of large territories. The order, emboldened byimperial approval,quickly resolved to establish an independentstate,without the consent of duke Konrad. Recognizing only papal authority and based on a solid economy, the order steadily expanded the Teutonic state during the following 150 years, engaging in several land disputes with its neighbors. Permanent conflicts with theKingdom of Poland,theGrand Duchy of Lithuania,and theNovgorod Republic,eventually led tomilitary defeatand containment by the mid-15th century. The lastGrand MasterAlbert of Brandenburgconverted toLutheranismin 1525 and turned the remaining lands of the order into the secularDuchy of Prussia.[100][101]

Church and state

[edit]

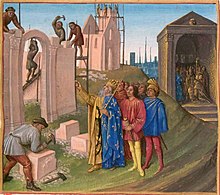

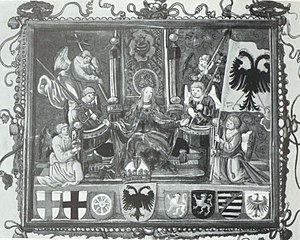

left to right:Archbishop of Cologne,Archbishop of Mainz,Archbishop of Trier,Count Palatine,Duke of Saxony,Margrave of BrandenburgandKing of Bohemia(Codex Balduini Trevirorum,c. 1340)

Henry V,great-grandson of Conrad II, who had overthrown his fatherHenry IVbecameHoly Roman Emperorin 1111. Hoping to gain greater control over the church inside the Empire, Henry V appointedAdalbert of Saarbrückenas the powerfularchbishop of Mainzin the same year. Adalbert began to assert the powers of the Church against secular authorities, that is, the Emperor. This precipitated the "Crisis of 1111" as yet another chapter of the long-termInvestiture Controversy.[102]In 1137, the prince-electors turned back to theHohenstaufenfamily for a candidate,Conrad III.Conrad tried to divest his rivalHenry the Proudof his two duchies—BavariaandSaxony—that led to war in southern Germany as the empire was divided into two powerful factions. The faction of theWelfsorGuelphs(in Italian) supported theHouse of Welfof Henry the Proud, which was the ruling dynasty in the Duchy of Bavaria. The rival faction of theWaiblingsorGhibellines(in Italian) pledged allegiance to theSwabianHouse of Hohenstaufen. During this early period, the Welfs generally maintained ecclesiastical independence under the papacy andpolitical particularism(the focus on ducal interests against the central imperial authority). The Waiblings, on the other hand, championed strict control of the church and a strong central imperial government.[103]

During the reign of theHohenstaufenemperorFrederick I(Barbarossa), an accommodation was reached in 1156 between the two factions. The Duchy of Bavaria was returned to Henry the Proud's sonHenry the Lion,duke ofSaxony,who represented theGuelphparty. However, theMargraviate of Austriawas separated from Bavaria and turned into the independentDuchy of Austriaby virtue of thePrivilegium Minusin 1156.[104]

Having become wealthy through trade, the confident cities of Northern Italy, supported by the Pope, increasingly opposed Barbarossa's claim of feudal rule(Honor Imperii)over Italy. The cities united in theLombard Leagueand finally defeated Barbarossa in theBattle of Legnanoin 1176. The following year a reconciliation was reached between the emperor andPope Alexander IIIin theTreaty of Venice.[105]The 1183Peace of Constanceeventually settled that the Italian cities remained loyal to the empire but were granted local jurisdiction and fullregal rightsin their territories.[106]

In 1180, Henry the Lion was outlawed, Saxony was divided, and Bavaria was given toOtto of Wittelsbach,who founded theWittelsbach dynasty,which was to rule Bavaria until 1918.

From 1184 to 1186, the empire underFrederick I Barbarossareached its cultural peak with theDiet of Pentecostheld atMainzand the marriage of his sonHenryin Milan to theNormanprincessConstance of Sicily.[107]The power of the feudal lords was undermined by the appointment ofministerials(unfree servants of the Emperor) as officials. Chivalry and the court life flowered, as expressed in the scholastic philosophy ofAlbertus Magnusand the literature ofWolfram von Eschenbach.[108]

Between 1212 and 1250,Frederick IIestablished a modern, professionally administered state from his base inSicily.He resumed the conquest of Italy, leading to further conflict with thePapacy.In the Empire, extensive sovereign powers were granted to ecclesiastical and secular princes, leading to the rise of independent territorial states. The struggle with the Pope sapped the Empire's strength, as Frederick II was excommunicated three times. After his death, the Hohenstaufen dynasty fell, followed by aninterregnumduring which there was no Emperor (1250–1273). This interregnum came to an end with the election of a small Swabian count, Rudolf of Habsburg, as emperor.[109][110]

The failure of negotiations between EmperorLouis IVand the papacy led to the 1338Declaration at Rhenseby six princes of theImperial Estateto the effect that election by all or the majority of the electors automatically conferred the royal title and rule over the empire, without papal confirmation. As result, the monarch was no longer subject to papal approbation and became increasingly dependent on the favour of the electors. Between 1346 and 1378Emperor Charles IVofLuxembourg,king of Bohemia, sought to restore imperial authority. The 1356 decree of theGolden Bullstipulated that all future emperors were to be chosen by a college of onlyseven– four secular and three clerical – electors. The secular electors were the King of Bohemia, theCount Palatineof the Rhine, the Duke ofSaxony,and the Margrave ofBrandenburg,the clerical electors were the Archbishops ofMainz,Trier,andCologne.[111]

Between 1347 and 1351 Germany and almost the entire European continent were consumed by the most severe outbreak of theBlack Deathpandemic.Estimated to have caused the abrupt death of 30 to 60% of Europe's population, it led to widespread social and economic disruption and deep religious disaffection and fanaticism. Minority groups, and Jews in particular were blamed, singled out andattacked.As a consequence, many Jews fled and resettled in Eastern Europe.[112][113]

Towns and cities

[edit]Total population estimates of the German territories range around 5 to 6 million by the end of Henry III's reign in 1056 and about 7 to 8 million after Friedrich Barbarossa's rule in 1190.[114][115]The vast majority were farmers, typically in a state ofserfdomunder feudal lords and monasteries.[103]Towns gradually emerged and in the 12th century many new cities were founded along the trading routes and near imperial strongholds and castles. The towns were subjected to themunicipal legal system.Cities such asCologne,that had acquired the status ofImperial Free Cities,were no longer answerable to the local landlords or bishops, but immediate subjects of the Emperor and enjoyed greater commercial and legal liberties.[116]The towns were ruled by a council of the – usuallymercantile– elite, thepatricians.Craftsmenformedguilds,governed by strict rules, which sought to obtain control of the towns; a few were open to women. Society had diversified, but was divided into sharply demarcated classes of theclergy,physicians,merchants,various guilds of artisans, unskilled day labourers andpeasants.Full citizenship was not available topaupers.Political tensions arose from issues of taxation, public spending, regulation of business, and market supervision, as well as the limits of corporate autonomy.[117]

Cologne'scentral location on theRhineriver placed it at the intersection of the major trade routes between east and west and was the basis of Cologne's growth.[118]The economic structures of medieval and early modern Cologne were characterized by the city's status as a major harbor and transport hub upon the Rhine. It was the seat of an archbishop, under whose patronage the vastCologne Cathedralwas built since 1240. The cathedral houses sacred Christian relics and it has since become a well knownpilgrimage destination.By 1288 the city had secured its independence from the archbishop (who relocated to Bonn), and was ruled by itsburghers.[119]

Learning and culture

[edit]BenedictineabbessHildegard von Bingenwrote several influential theological, botanical, and medicinal texts, as well as letters, liturgical songs, poems, and arguably the oldest survivingmorality play,Ordo Virtutum,while supervising brilliant miniatureIlluminations.About 100 years later,Walther von der Vogelweidebecame the most celebrated of theMinnesänger,who wereMiddle High Germanlyric poets.

Around 1439,Johannes GutenbergofMainz,usedmovable typeprinting and issued theGutenberg Bible.He was the global inventor of theprinting press,thereby starting thePrinting Revolution.Cheap printed books and pamphlets played central roles for the spread of theReformationand theScientific Revolution.

Around the transition from the 15th to the 16th century,Albrecht DürerfromNurembergestablished his reputation across Europe aspainter,printmaker,mathematician,engraver,andtheoristwhen he was still in his twenties and secured his reputation as one of the most important figures of theNorthern Renaissance.

-

Hildegard von Bingen,Benedictine abbess, philosopher, author, artist and visionary naturalist

-

Albertus Magnus,bishop, philosopher, theologian,Doctor of the Church

-

Hans Memling's religious works often incorporateddonor portraitsof the clergymen, aristocrats, andburghers(bankers, merchants, and politicians) who were his patrons[120]

-

Albrecht Dürer,one of the most influential artists of theNorthern Renaissance

-

Tilman Riemenschneider,most accomplished sculptor, woodcarver and master in stone from the lateGothicto theRenaissance

-

Matthias Grünewaldwas aGerman Renaissancepainter of religious works who ignored Renaissanceclassicismto continue the style of late medieval Central European art into the 16th century.

-

Adam Riesis known as the "father of modern calculating" because of his decisive contribution to the recognition thatRoman numeralsare unpractical and to their replacement by the considerably more practicalArabic numerals.[121]

-

Georgius Agricolawas the first to drop the Arabic definite articleal-,exclusively writingchymiaandchymistadescribingchemistry.[122][123]He is generally referred to as the father ofmineralogyand the founder ofgeologyas a scientific discipline.[124][123]

-

Hans Holbein the Youngeris considered one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century.[125]

Early modern Germany

[edit]- SeeList of states in the Holy Roman Empirefor subdivisions and the political structure

Social changes

[edit]

The early-modern European society gradually developed after the disasters of the 14th century as religious obedience and political loyalties declined in the wake of theGreat Plague,theschismof the Church and prolonged dynastic wars. The rise of thecitiesand the emergence of the newburgherclass eroded the societal, legal and economic order of feudalism.[127]

The commercial enterprises of the mercantile elites in the quickly developing cities in South Germany (such asAugsburgandNuremberg), with the most prominent families being theGossembrots,Fuggers(the wealthiest family in Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries[130]),Welsers,Hochstetters,Imholts, generated unprecedented financial means. As financiers to both the leading ecclesiastical and secular rulers, these families fundamentally influenced the political affairs in the empire during the fifteenth and sixteenth century.[131][132][133][134]The increasingly money based economy also provoked social discontent among knights and peasants and predatory "robber knights" became common.[135]

From 1438 theHabsburgdynasty, who had acquired control in the south-eastern empire over the Duchy of Austria,BohemiaandHungaryafter the death of KingLouis IIin 1526, managed to permanently occupy the position of the Holy Roman Emperor until 1806 (with the exception of the years between 1742 and 1745).

Some Europe-wide revolutions were born in the Empire: the combination of thefirst modern postal systemestablished byMaximilian(with the management under theTaxis family) with the printing system invented by Gutenberg produced a communication revolution[136][137][138]– the Empire's decentralized nature made censorship difficult and this combined with the new communication system to facilitate free expression, thus elevating cultural life. The system also helped the authorities to disseminate orders and policies, boosted the Empire's coherence in general, and helped reformers like Luther to broadcast their views and communicate with each other effectively, thus contributing to the religious Reformation.[139][140][141]

Maximilian'smilitary reforms,especially his development of theLandsknechte,caused a military revolution that broke the back of the knight class[142][143]and spread all over Europe shortly after his death.[144][145]

Imperial reform

[edit]

During his reign from 1493 to 1519,Maximilian I,in a combined effort with the Estates (who sometimes acted as opponents and sometimes as cooperators to him), his officials and his humanists,reformedthe empire. A dual system of Supreme Courts (theReichskammergerichtand theReichshofrat) was established (with theReichshofratplaying a more efficient role during the Early Modern period),[150]together with the formalized Reception of Roman Law;[151][152][153][154]theImperial Diet(Reichstag) became the all-important political forum and the supreme legal and constitutional institution, which would act as a guarantee for the preservation of the Empire in the long run;[155][156]a Permanent Land Piece (Ewiger Landfriede) was declared in 1495 with regional leagues and unions providing the supporting structure, together with the creation of theReichskreise(Imperial Circles,which would serve the purpose of organize imperial armies, collect taxes and enforce orders of the imperial institutions);[157][158][159]the Imperial and Court Chanceries were combined to become the decisive government institution;[160][161]theLandsknechtethat Maximilian created became a form of imperial army;[162]a national political culture began to emerge;[163][164]and the German language began to attain an unified form.[165][166]The political structure remained incomplete and piecemeal though, mainly due to the failure of the Common Penny (an imperial tax) that the Estates resisted.[150][a]Through many compromises between emperor and estates though, a flexible, future-oriented problem-solving mechanism for the Empire was formed, together with a monarchy through which the emperor shared power with the Estates.[168][b]Whether the Reform also equated to a (successful or unsuccessful) nation building process remains a debate.[170]

The additionNationis Germanicæ(of German Nation) to the emperor's title appeared first in the 15th century: in a 1486 law decreed by Frederick III and in 1512 in reference to the Imperial Diet in Cologne by Maximilian I. In 1525, the Heilbronn reform plan – the most advanced document of theGerman Peasants' War(Deutscher Bauernkrieg) – referred to theReichasvon Teutscher Nation(of German nation). During the fifteen century, the term "German nation" had witness a rise in use due to the growth of a "community of interests". The Estates also increasingly distinguished between their German Reich and the wider, "universal" Reich.[171]

Protestant Reformation

[edit]

In order to manage their ever growing expenses, theRenaissance Popesof the 15th and early 16th century promoted the excessive sale ofindulgencesand offices and titles of the Roman Curia.

In 1517, the monkMartin Lutherpublished a pamphlet with95 Thesesthat he posted in the town square ofWittenbergand handed copies of to feudal lords. Whether he nailed them to a church door at Wittenberg remains unclear. The list detailed 95 assertions, he argued, represented corrupt practice of the Christian faith and misconduct within the Catholic Church. Although perhaps not Luther's chief concern, he received popular support for his condemnation of the sale ofindulgencesand clerical offices, the pope's and higher clergy's abuse of power and his doubts of the very idea of the institution of the Church and the papacy.[172]

TheProtestant Reformationwas the first successful challenge to the Catholic Church and began in 1521 as Luther was outlawed at theDiet of Wormsafter his refusal to repent. The ideas of the reformation spread rapidly, as the new technology of the modern printing press ensured cheap mass copies and distribution of the theses and helped by theEmperor Charles V's wars with France and theTurks.[172]Hiding in theWartburg Castle,Luther translated the Bible into German, thereby greatly contributing to the establishment of the modern German language. This is highlighted by the fact that Luther spoke only a local dialect of minor importance during that time. After the publication of his Bible, his dialect suppressed others and constitutes to a great extent what is now modern German. With theprotestationof the Lutheran princes at theImperial DietofSpeyerin 1529 and the acceptance and adoption of the LutheranAugsburg Confessionby the Lutheran princes beginning in 1530, the separate Lutheran church was established.[173]

TheGerman Peasants' War,which began in the southwest inAlsaceandSwabiaand spread further east intoFranconia,Thuringiaand Austria, was a series of economic and religious revolts of the rural lower classes, encouraged by the rhetoric of various radical religious reformers and Anabaptists against the ruling feudal lords. Although occasionally assisted by war-experienced noblemen likeGötz von BerlichingenandFlorian Geyer(in Franconia) and the theologianThomas Müntzer(in Thuringia), the peasant forces lacked military structure, skill, logistics and equipment and as many as 100,000 insurgents were eventually defeated and massacred by the territorial princes.[174]

The CatholicCounter-Reformation,initiated in 1545 at theCouncil of Trentwas spearheaded by the scholarly religiousJesuit order,that was founded just five years prior by several clerics aroundIgnatius of Loyola.Its intent was to challenge and contain the Protestant Reformation via apologetic and polemical writings and decrees, ecclesiastical reconfiguration, wars and imperial political maneuverings. In 1547, emperor Charles V defeated theSchmalkaldic League,a military alliance of Protestant rulers.[175]The 1555Peace of Augsburgdecreed the recognition of the Lutheran Faith and religious division of the empire. It also stipulated the ruler's right to determine the official confession in his principality (Cuius regio, eius religio). The Counter-Reformation eventually failed to reintegrate the central and northern German Lutheran states. In 1608/1609 theProtestant Unionand theCatholic Leaguewere formed.

Thirty Years' War, 1618–1648

[edit]

The 1618 to 1648Thirty Years' War,that took place almost exclusively in the Holy Roman Empire has its origins, which remain widely debated, in the unsolved and recurring conflicts of the Catholic and Protestant factions. The Catholic emperorFerdinand IIattempted to achieve the religious and political unity of the empire, while the opposing Protestant Union forces were determined to defend their religious rights. The religious motive served as the universal justification for the various territorial and foreign princes, who over the course of several stages joined either of the two warring parties in order to gain land and power.[176][177]

The conflict was sparked by therevolt of the Protestant nobility of Bohemiaagainst emperorMatthias' succession policies. After imperial triumph at theBattle of White Mountainand a short-lived peace, the war grew to become a political European conflict by the intervention ofKing Christian IV of Denmarkfrom 1625 to 1630,Gustavus Adolphus of Swedenfrom 1630 to 1648 and France underCardinal Richelieufrom 1635 to 1648. The conflict increasingly evolved into a struggle between the French House of Bourbon and the House of Habsburg for predominance in Europe, for which the central German territories of the empire served as the battleground.[178]

The war ranks among the most catastrophic in history as three decades of constant warfare and destruction had left the land devastated. Marauding armies incessantly pillaged the countryside, seized and levied heavy taxes on cities and indiscriminately plundered the food stocks of the peasantry. There were also the countless bands of murderous outlaws, sick, homeless, disrupted people and invalid soldiery. Overall social and economic disruption caused a dramatic decline in population as a result of pandemic murder and random rape and killings, endemic infectious diseases, crop failures, famine, declining birth rates, wanton burglary, witch-hunts and the emigration of terrified people. Estimates vary between a 38% drop from 16 million people in 1618 to 10 million by 1650 and a mere 20% drop from 20 million to 16 million. TheAltmarkandWürttembergregions were especially hard hit, where it took generations to fully recover.[176][179]

The war was the last major religious struggle in mainland Europe and ended in 1648 with thePeace of Westphalia.It resulted in increased autonomy for the constituent states of the Holy Roman Empire, limiting the power of the emperor. Most ofAlsacewas ceded to France,Western PomeraniaandBremen-Verdenwere given to Sweden as Imperial fiefs, and the Netherlands officially left the Empire.[180]

Culture and literacy

[edit]

The population of Germany reached about twenty million people by the mid-16th century, the great majority of whom were peasant farmers.[182]

TheProtestant Reformationwas a triumph forliteracyand the newprinting press.[183][c][185][186]Luther's translation of the Bible into High German(theNew Testamentwas published in 1522; theOld Testamentwas published in parts and completed in 1534) was a decisive impulse for the increase of literacy inearly modern Germany,[181]and stimulated printing and distribution of religious books and pamphlets. From 1517 onward religious pamphlets flooded Germany and much of Europe. The Reformation instigated a media revolution as by 1530 over 10,000 individual works are published with a total of ten million copies. Luther strengthened his attacks on Rome by depicting a "good" against "bad" church. It soon became clear that print could be used for propaganda in the Reformation for particular agendas. Reform writers used pre-Reformation styles, clichés, and stereotypes and changed items as needed for their own purposes.[187]Especially effective were Luther'sSmall Catechism,for use of parents teaching their children, andLarger Catechism,for pastors.[188]Using the German vernacular they expressed the Apostles' Creed in simpler, more personal, Trinitarian language. Illustrations in the newly translated Bible and in many tracts popularized Luther's ideas.Lucas Cranach the Elder,the painter patronized by the electors of Wittenberg, was a close friend of Luther, and illustrated Luther's theology for a popular audience. He dramatized Luther's views on the relationship between the Old and New Testaments, while remaining mindful of Luther's careful distinctions about proper and improper uses of visual imagery.[189]

Luther's translation of the Bible into High Germanwas also decisive for theGerman languageand its evolution fromEarly New High Germanto Modern Standard German.[181]The publication of Luther's Bible was a decisive moment in the spread of literacy inearly modern Germany,[181]and promoted the development of non-local forms of language and exposed all speakers to forms of German from outside their own area.[190]

Science

[edit]

Notable late fifteenth to early eighteenth-centurypolymathsinclude:Johannes Trithemius,one of the founder of modern cryptography, founder ofsteganography,as well asbibliographyand literary studies as branches of knowledge;[191][192][193]Conrad Celtes,the first and foremost German cartographic writer and "the greatest lyric genius and certainly the greatest organizer and popularizer of German Humanism";[194][195][196][197]Athanasius Kircher,described by Fletcher as "a founder figure of various disciplines—of geology (certainly vulcanology), musicology (as a surveyor of musical forms), museum curatorship, Coptology, to name a few—and might be claimed today as the first theorist of gravity and a long-term originator of the moving pictures (with his magic lantern shows). Through his many enthusiasms, moreover, he was the conduit of others' pursuits in the rapidly widening horizon of knowledge that marks the later Renaissance.";[198]andGottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,one of the greatest, if not the greatest "Universal genius", of all times.[199][200]

Cartography developed strongly, with the center being Nuremberg, at the beginning of the sixteenth century.Martin WaldseemüllerandMatthias Ringmann'sUniversalis Cosmographiaand the 1513 edition ofGeographymarked the climax of a cartography revolution.[201][202]The emperor himself dabbled in cartography.[203]

In 1515,Johannes Stabius(court astronomer under Maximilian I),Albrecht Dürerand the astronomerKonrad Heinfogelproduced the first planispheres of both southern and northerns hemispheres, also the first printed celestial maps. These maps prompted the revival of interest in the field of uranometry throughout Europe.[204][205][206][207]

AstronomerJohannes KeplerfromWeil der Stadtwas one of the pioneering minds of empirical and rational research. Through rigorous application of the principles of theScientific methodhe construed hislaws of planetary motion.His ideas influenced contemporary Italian scientistGalileo Galileiand provided fundamental mechanical principles forIsaac Newton's theory ofuniversal gravitation.[208]

-

Johannes Kepler,one of the founders and fathers of modernastronomy,thescientific method,naturalandmodern science[209][210][211]

-

Otto von Guericke,scientist, inventor and politician, famous for demonstrating the power of atmospheric pressure with theMagdeburg hemispheres

-

Elisabeth of the Palatinate,philosopher, critic ofRené Descartes' dualistic metaphysics

-

Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen,author of the novelSimplicius Simplicissimus

-

Athanasius Kircher,polymath

-

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,philosopher and mathematician

-

Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus,mathematician, physicist, physician, philosopher, co-inventor of European porcelain

Colonies

[edit]German Colonies in the Americas existed because theFree Imperial CitiesofAugsburgandNuremberggot colonial rights in theProvince of Venezuelaor North of South America in return for debts owed by theHoly Roman EmpireCharles V,who was also King of Spain. In 1528, Charles V issued a charter by which theWelser familypossessed the rights to explore, rule and colonize the area, also with the motivation of searching for the legendary golden city ofEl Dorado.Their principal colony wasKlein-Venedig.A never realized colonial project wasHanauish-Indiesintended byFriedrich Casimir, Count of Hanau-Lichtenbergas a fief of theDutch West India Company.The project failed due to a lack of funds and the outbreak of theFranco-Dutch Warin 1672.

1648–1815

[edit]Rise of Prussia

[edit]

Frederick William,ruler ofBrandenburg-Prussiasince 1640 and later called the GreatElector,acquiredEast Pomeraniavia thePeace of Westphaliain 1648. He reorganized his loose and scattered territories and managed to throw off the vassalage of Prussia under the Kingdom of Poland during theSecond Northern War.[212]In order to address the demographic problem of Prussia's largely rural population of about three million, he attracted the immigration and settlement of FrenchHuguenotsin urban areas. Many became craftsmen and entrepreneurs.[213]King Frederick William I,known as theSoldier King,who reigned from 1713 to 1740, established the structures for the highly centralized Prussian state and raised a professional army, that was to play a central role.[214]He also successfully operated a command economy that some historians consider mercantilist.[215][216]

The total population of Germany (in its1914 territorial extent) grew from 16 million in 1700 to 17 million in 1750 and reached 24 million in 1800. The 18th-century economy noticeably profited from widespread practical application of the Scientific method as greater yields and a more reliable agricultural production and the introduction of hygienic standards positively affected the birth rate – death rate balance.[217]

Wars

[edit]

Louis XIV of Francewaged a series of successful wars in order to extend the French territory. He occupiedLorraine(1670) and annexed the remainder of Alsace (1678–1681) that included the free imperial city ofStraßburg.At the start of theNine Years' War,he also invaded theElectorate of the Palatinate(1688–1697).[218]Louis established a number ofcourtswhose sole function was to reinterpret historic decrees and treaties, theTreaties of Nijmegen(1678) and thePeace of Westphalia(1648) in particular in favor of his policies of conquest. He considered the conclusions of these courts, theChambres de réunionas sufficient justification for his boundless annexations. Louis' forces operated inside the Holy Roman Empire largely unopposed, because all available imperial contingents fought in Austria in theGreat Turkish War.TheGrand Allianceof 1689 took up arms against France and countered any further military advances of Louis. The conflict ended in 1697 as both parties agreed to peace talks after either side had realized, that a total victory was financially unattainable. TheTreaty of Ryswickprovided for the return of the Lorraine and Luxembourg to the empire and the abandoning of French claims to the Palatinate.[219]

After the last-minuterelief of Viennafrom a siege and the imminent seizure by aTurkish forcein 1683, the combined troops of theHoly League,that had been founded the following year, embarked on the military containment of theOttoman Empireand reconqueredHungaryin 1687.[220]ThePapal States,the Holy Roman Empire, thePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth,theRepublic of Veniceand since 1686Russiahad joined the league under the leadership ofPope Innocent XI.Prince Eugene of Savoy,who served under emperor Leopold I, took supreme command in 1697 and decisively defeated the Ottomans in a series of spectacular battles and manoeuvres. The 1699Treaty of Karlowitzmarked the end of the Great Turkish War and Prince Eugene continued his service for theHabsburg monarchyas president of theWar Council.He effectively ended Turkish rule over most of the territorial states in theBalkansduring theAustro-Turkish War of 1716–1718.TheTreaty of Passarowitzleft Austria to freely establish royal domains in Serbia and the Banat and maintain hegemony inSoutheast Europe,on which the futureAustrian Empirewas based.[221][222]

Enlightened absolutism

[edit]

Frederick II "the Great"is best known for his military genius and unique utilisation of the highly organized army to make Prussia one of the great powers in Europe as well asescaping from almost certain national disasterat the last minute. He was also an artist, author and philosopher, who conceived and promoted the concept ofenlightened absolutism.[223][224]

Austrian empressMaria Theresasucceeded in bringing about a favorable conclusion for her inthe 1740 to 1748 warfor recognition of her succession to the throne. However,Silesiawas permanently lost to Prussia as a consequence of theSilesian Warsand theSeven Years' War.The 1763Treaty of Hubertusburgruled that Austria and Saxony had to relinquish all claims to Silesia. Prussia, that had nearly doubled its territory was eventually recognized as a great European power with the consequence that the politics of the following century were fundamentally influenced byGerman dualism,the rivalry of Austria and Prussia for supremacy in Central Europe.[225]

The concept of enlightened absolutism, although rejected by the nobility and citizenry, was advocated inPrussiaandAustriaand implemented since 1763. Prussian kingFrederick IIdefended the idea in an essay and argued that thebenevolent monarchsimply is thefirst servant of the state,who effects his absolute political power for the benefit of the population as a whole. A number of legal reforms (e.g. the abolition of torture and the emancipation of the rural population and the Jews), the reorganization of thePrussian Academy of Sciences,the introduction of compulsory education for boys and girls and promotion of religious tolerance, among others, caused rapid social and economic development.[226]

During 1772 to 1795 Prussia instigated thepartitions of Polandby occupying the western territories of the formerPolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.Austria andRussiaresolved to acquire the remaining lands with the effect that Poland ceased to exist as a sovereign state until 1918.[227]

Smaller states

[edit]

The smaller German states were overshadowed by Prussia and Austria.Bavariahad arural economy.Saxonywas in economically good shape, although numerous wars had taken their toll. During the time when Prussia rose rapidly within Germany, Saxony was distracted by foreign affairs. The House of Wettin concentrated on acquiring and then holding on to the Polish throne which was ultimately unsuccessful.[228][clarification needed]

Many of the smaller states of Germany were run by bishops, who in reality were from powerful noble families and showed scant interest in religion. While none of the later ecclesial rulers reached the outstanding reputation of Mainz'Johann Philipp von Schönbornor Münster'sChristoph Bernhard von Galen,some of them promotedEnlightenmentlike the benevolent and progressiveFranz Ludwig von ErthalinWürzburgandBamberg.[229]

InHesse-Kassel,the LandgraveFrederick II,ruled from 1760 to 1785 as an enlightened despot, and raised money by renting soldiers (called "Hessians") toGreat Britainto help fight theAmerican Revolutionary War.He combined Enlightenment ideas with Christian values,cameralistplans for central control of the economy, and a militaristic approach toward diplomacy.[230]

Hanoverdid not have to support a lavish court—its rulers were also kings of England and resided in London.George III,elector (ruler) from 1760 to 1820, never once visited Hanover. The local nobility who ran the country opened theUniversity of Göttingenin 1737; it soon became a world-class intellectual center.Badensported perhaps the best government of the smaller states.Karl Friedrichruled for 73 years and was an enthusiast for the Enlightenment; he abolished serfdom in 1783.[231]

The smaller states failed to form coalitions with each other, and were eventually overwhelmed by Prussia who swallowed up many of them between 1807 and 1871.[232]

Social changes

[edit]Prussiaunderwent majorsocial changebetween the mid-17th and mid-18th centuries as thenobilitydeclined as the traditionalaristocracystruggled to compete with the risingmerchant class,[233]which developed into a newBourgeoisiemiddle class,[234][235][236]while theemancipation of the serfsgranted the ruralpeasantryland purchasing rights and freedom of movement,[237]and a series ofagrarian reformsin northwestern Germany abolishedfeudal obligationsand divided up feudal land, giving rise to wealthier peasants and paved the way for a more efficientrural economy.[238]

Enlightenment

[edit]

During the mid-18th century, the recognition and application of Enlightenment cultural, intellectual and spiritual ideals and standards, led to a flourishing of art, music, philosophy, science and literature. The philosopherChristian Wolffwas a pioneering author in a vast number of fields of Enlightenment rationality, and established German as the prevailing language of philosophical reasoning, scholarly instruction and research.[239]

In 1685, MargraveFrederick Williamof Prussia issued theEdict of Potsdamwithin a week after French kingLouis XIV'sEdict of Fontainebleau,that decreed the abolishment of the 1598concessionto free religious practice forProtestants.Frederick William offered hisco-religionists, who are oppressed and assailed for the sake of the Holy Gospel and its pure doctrine...a secure and free refuge in all Our Lands.[240]Around 20,000 Huguenot refugees arrived in an immediate wave and settled in the cities, 40% in Berlin, the ducal residence alone. The French Lyceum in Berlin was established in 1689 and the French language had by the end of the 17th century replaced Latin to be spoken universally in international diplomacy. The nobility and the educated middle-class of Prussia and the various German states increasingly used the French language in public conversation in combination with universal cultivated manners. Like no other German state, Prussia had access to and the skill set for the application of pan-European Enlightenment ideas to develop more rational political and administrative institutions.[241]The princes of Saxony carried out a comprehensive series of fundamental fiscal, administrative, judicial, educational, cultural and general economic reforms. The reforms were aided by the country's strong urban structure and influential commercial groups, who modernized pre-1789 Saxony along the lines of classic Enlightenment principles.[242]

Johann Gottfried von Herderbroke new ground in philosophy and poetry, as a leader of theSturm und Drangmovement of proto-Romanticism.Weimar Classicism( "Weimarer Klassik" ) was a cultural and literary movement based in Weimar that sought to establish a new humanism by synthesizing Romantic, classical, and Enlightenment ideas. The movement, from 1772 until 1805, involved Herder as well as polymathJohann Wolfgang von GoetheandFriedrich Schiller,a poet and historian. Herder argued that every folk had its own particular identity, which was expressed in its language and culture. This legitimized the promotion of German language and culture and helped shape the development of German nationalism. Schiller's plays expressed the restless spirit of his generation, depicting the hero's struggle against social pressures and the force of destiny.[243]

German music, sponsored by the upper classes, came of age under composersJohann Sebastian Bach,Joseph Haydn,andWolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[244]

KönigsbergphilosopherImmanuel Kanttried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom, and political authority. Kant's work contained basic tensions that would continue to shape German thought – and indeed all of European philosophy – well into the 20th century.[245][246]The ideas of the Enlightenment and their implementation received general approval and recognition as principal cause for widespread cultural progress.[247]

French Revolution, 1789–1815

[edit]

German reaction to theFrench Revolutionwas mixed at first. German intellectuals celebrated the outbreak, hoping to see the triumph of Reason and The Enlightenment. The royal courts in Vienna and Berlin denounced the overthrow of the king and the threatened spread of notions of liberty, equality, and fraternity. By 1793, theexecution of the French kingand the onset ofthe Terrordisillusioned the Bildungsbürgertum (educated middle classes). Reformers said the solution was to have faith in the ability of Germans to reform their laws and institutions in peaceful fashion.[248]

Europe was racked by two decades of war revolving around France's efforts to spread its revolutionary ideals, and the opposition of reactionary royalty. War broke out in 1792 as Austria and Prussia invaded France, but were defeated at theBattle of Valmy(1792). The German lands saw armies marching back and forth, bringing devastation (albeit on a far lower scale than theThirty Years' War,almost two centuries before), but also bringing new ideas of liberty and civil rights for the people. Prussia and Austria ended their failed wars with France but (with Russia) partitioned Poland among themselves in 1793 and 1795.

French consulate suzerainty

[edit]Francetook control of theRhineland,imposed French-style reforms, abolished feudalism, established constitutions, promoted freedom of religion, emancipated Jews, opened the bureaucracy to ordinary citizens of talent, and forced the nobility to share power with the rising middle class. Napoleon created theKingdom of Westphaliaas a model state.[249]These reforms proved largely permanent and modernized the western parts of Germany. When the French tried to impose the French language, German opposition grew in intensity. ASecond Coalitionof Britain, Russia, and Austria then attacked France but failed. Napoleon established direct or indirect control over most of western Europe, including the German states apart from Prussia and Austria. The old Holy Roman Empire was little more than a farce; Napoleon simply abolished it in 1806 while forming new countries under his control. In Germany Napoleon set up the "Confederation of the Rhine",comprising most of the German states except Prussia and Austria.[250]

Imperial French suzerainty

[edit]UnderFrederick William II's weak rule (1786–1797) Prussia had undergone a serious economic, political and military decline. His successor kingFrederick William IIItried to remain neutral during theWar of the Third CoalitionandFrench emperorNapoleon's dissolution of theHoly Roman Empireand reorganisation of the German principalities. Induced by the queen and a pro-war party Frederick William joined theFourth Coalitionin October 1806. Napoleon easily defeated the Prussian army at theBattle of Jenaand occupied Berlin. Prussia lost its recently acquired territories in western Germany, its army was reduced to 42,000 men, no trade with Britain was allowed and Berlin had to pay Paris high reparations and fund the French army of occupation.Saxonychanged sides to support Napoleon and joined theConfederation of the Rhine.RulerFrederick Augustus Iwas rewarded with the title of king and given a part of Poland taken from Prussia, which became known as theDuchy of Warsaw.[251]

AfterNapoleon's military fiasco in Russia in 1812,Prussia allied with Russia in theSixth Coalition.A series of battles followed and Austria joined the alliance. Napoleon was decisively defeated in theBattle of Leipzigin late 1813. The German states of the Confederation of the Rhine defected to the Coalition against Napoleon, who rejected any peace terms. Coalition forces invaded France in early 1814,Paris felland in April Napoleon surrendered. Prussia as one of the winners at theCongress of Vienna,gained extensive territory.[217]

1815–1871

[edit]Overview

[edit]

In 1815, continental Europe was in a state of overall turbulence and exhaustion, as a consequence of theFrench RevolutionaryandNapoleonic Wars.The liberal spirit of theEnlightenmentand Revolutionary era diverged towardRomanticism.[252]The victorious members of the Coalition had negotiated a new peaceful balance of powers in Vienna and agreed to maintain a stable German heartland that keeps French imperialism at bay. However, the idea of reforming the defunctHoly Roman Empirewas discarded. Napoleon'sreorganization of the German stateswas continued and the remaining princes were allowed to keep their titles. In 1813, in return for guarantees from the Allies that the sovereignty and integrity of the Southern German states (Baden,Württemberg,andBavaria) would be preserved, they broke with France.[253]

German Confederation

[edit]During the 1815Congress of Viennathe 39 former states of theConfederation of the Rhinejoined theGerman Confederation,a loose agreement for mutual defense. Attempts of economic integration and customs coordination were frustrated by repressive anti-national policies. Great Britain approved of the union, convinced that a stable, peaceful entity in central Europe could discourage aggressive moves by France or Russia. Most historians, however, concluded, that the Confederation was weak and ineffective and an obstacle to German nationalism. The union was undermined by the creation of theZollvereinin 1834, the1848 revolutions,the rivalry between Prussia and Austria and was finally dissolved in the wake of theAustro-Prussian Warof 1866,[254]to be replaced by theNorth German Confederationduring the same year.[254]

Society and economy

[edit]Increasingly after 1815, a centralized Prussian government based in Berlin took over the powers of the nobles, which in terms of control over the peasantry had been almost absolute. To help the nobility avoid indebtedness, Berlin set up a credit institution to provide capital loans in 1809, and extended the loan network to peasants in 1849. When the German Empire was established in 1871, the Junker nobility controlled the army and the navy, the bureaucracy, and the royal court; they generally set governmental policies.[255]

Population

[edit]

Between 1815 and 1865 the population of the German Confederation (excluding Austria) grew around 60% from 21 million to 34 million.[256]Simultaneously theDemographic Transitiontook place as the high birth rates and high death rates of the pre-industrial country shifted to low birth and death rates of the fast-growing industrialized urban economic and agricultural system. Increased agricultural productivity secured a steady food supply, as famines and epidemics declined. This allowed people to marry earlier, and have more children. The high birthrate was offset by a very high rate of infant mortality and after 1840, large-scale emigration to theUnited States.Emigration totaled at 480,000 in the 1840s, 1,200,000 in the 1850s, and at 780,000 in the 1860s. The upper and middle classes first practiced birth control, soon to be universally adopted.[257]

Industrialization

[edit]

In 1800, Germany's social structure was poorly suited to entrepreneurship or economic development. Domination by France during the French Revolution (1790s to 1815), however, produced important institutional reforms, that included the abolition of feudal restrictions on the sale of large landed estates, the reduction of the power of the guilds in the cities, and the introduction of a new, more efficient commercial law. The idea, that these reforms were beneficial for Industrialization has been contested.[258]

In the early 19th century the Industrial Revolution was in full swing in Britain, France, and Belgium. The various small federal states in Germany developed only slowly and independently as competition was strong. Early investments for the railway network during the 1830s came almost exclusively from private hands. Without a central regulatory agency the construction projects were quickly realized. Actual industrialization only took off after 1850 in the wake of the railroad construction.[259]The textile industry grew rapidly, profiting from the elimination of tariff barriers by the Zollverein.[260][261]During the second half of the 19th century the German industry grew exponentially and by 1900, Germany was an industrial world leader along with Britain and the United States.[262]</ref>

Urbanization

[edit]In 1800, the population was predominantly rural, as only 10% lived in communities of 5,000 or more people, and only 2% lived in cities of more than 100,000 people. After 1815, the urban population grew rapidly, due to the influx of young people from the rural areas. Berlin grew from 172,000 in 1800, to 826,000 inhabitants in 1870, Hamburg from 130,000 to 290,000, Munich from 40,000 to 269,000 and Dresden from 60,000 to 177,000.[263]

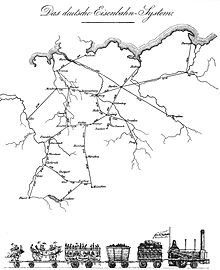

Railways

[edit]

The takeoff stage of economic development came with the railroad revolution in the 1840s, which opened up new markets for local products, created a pool of middle managers, increased the demand for engineers, architects and skilled machinists and stimulated investments in coal and iron. Political disunity of three dozen states and a pervasive conservatism made it difficult to build railways in the 1830s. However, by the 1840s, trunk lines did link the major cities; each German state was responsible for the lines within its own borders. EconomistFriedrich Listsummed up the advantages to be derived from the development of the railway system in 1841:

- 1. As a means of national defence, it facilitates the concentration, distribution and direction of the army.

- 2. It is a means to the improvement of the culture of the nation. It brings talent, knowledge and skill of every kind readily to market.

- 3. It secures the community against dearth and famine, and against excessive fluctuation in the prices of the necessaries of life.

- 4. It promotes the spirit of the nation, as it has a tendency to destroy the Philistine spirit arising from isolation and provincial prejudice and vanity. It binds nations by ligaments, and promotes an interchange of food and of commodities, thus making it feel to be a unit. The iron rails become a nerve system, which, on the one hand, strengthens public opinion, and, on the other hand, strengthens the power of the state for police and governmental purposes.[264]