History of botany

Thehistory of botanyexamines the human effort to understand life on Earth by tracing the historical development of the discipline ofbotany—that part of natural science dealing with organisms traditionally treated as plants.

Rudimentary botanical science began with empirically based plant lore passed from generation to generation in the oral traditions ofpaleolithichunter-gatherers.The first writings that show human curiosity about plants themselves, rather than the uses that could be made of them, appear inancient Greeceand ancient India. In Ancient Greece, the teachings ofAristotle's studentTheophrastusat theLyceuminancient Athensin about 350 BC are considered the starting point for Western botany. In ancient India, the Vṛkṣāyurveda, attributed toParashara,is also considered one of the earliest texts to describe various branches of botany.[1]

In Europe, botanical science was soon overshadowed by amedievalpreoccupation with the medicinal properties of plants that lasted more than 1000 years. During this time, the medicinal works of classical antiquity were reproduced in manuscripts and books calledherbals.In China and the Arab world, theGreco-Romanwork on medicinal plants was preserved and extended.

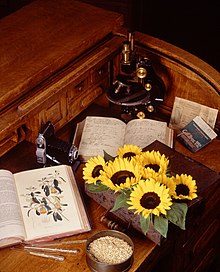

In Europe, theRenaissanceof the 14th–17th centuries heralded a scientific revival during which botany gradually emerged fromnatural historyas an independent science, distinct from medicine and agriculture.Herbalswere replaced byfloras:books that described the native plants of local regions. The invention of themicroscopestimulated the study ofplant anatomy,and the first carefully designed experiments inplant physiologywere performed. With the expansion of trade and exploration beyond Europe, the many new plants being discovered were subjected to an increasingly rigorous process ofnaming,description, andclassification.

Progressively more sophisticated scientific technology has aided the development of contemporary botanical offshoots in the plant sciences, ranging from the applied fields ofeconomic botany(notably agriculture, horticulture and forestry), to the detailed examination of the structure and function of plants and their interaction with the environment over many scales from the large-scale global significance of vegetation and plant communities (biogeographyandecology) through to the small scale of subjects likecell theory,molecular biologyand plantbiochemistry.

Introduction

[edit]Botany(GreekΒοτάνη(botanē) meaning "pasture","herbs""grass",or"fodder";[2]Medieval Latinbotanicus– herb, plant)[3]andzoologyare, historically, the core disciplines ofbiologywhose history is closely associated with the natural scienceschemistry,physicsandgeology.A distinction can be made between botanical science in a pure sense, as the study of plants themselves, and botany as applied science, which studies the human use of plants. Earlynatural historydivided pure botany into three main streamsmorphology-classification,anatomyandphysiology– that is, external form, internal structure, and functional operation.[4]The most obvious topics in applied botany arehorticulture,forestryandagriculturealthough there are many others likeweed science,plant pathology,floristry,pharmacognosy,economic botanyandethnobotanywhich lie outside modern courses in botany. Since the origin of botanical science there has been a progressive increase in the scope of the subject as technology has opened up new techniques and areas of study. Modernmolecular systematics,for example, entails the principles and techniques oftaxonomy,molecular biology,computer scienceand more.

Within botany, there are a number of sub-disciplines that focus on particular plant groups, each with their own range of related studies (anatomy, morphology etc.). Included here are:phycology(algae),pteridology(ferns),bryology(mossesandliverworts) andpalaeobotany(fossil plants) and their histories are treated elsewhere (see side bar). To this list can be addedmycology,the study offungi,which were once treated as plants, but are now ranked as a unique kingdom.

Ancient knowledge

[edit]Nomadichunter-gatherersocieties passed on, byoral tradition,what they knew (their empirical observations) about the different kinds of plants that they used for food, shelter, poisons, medicines, for ceremonies and rituals etc. The uses of plants by these pre-literate societies influenced the way the plants were named and classified—their uses were embedded infolk-taxonomies,the way they were grouped according to use in everyday communication.[5]The nomadic life-style was drastically changed when settled communities were established in about twelve centres around the world during theNeolithic Revolutionwhich extended from about 10,000 to 2500 years ago depending on the region. With these communities came the development of the technology and skills needed for thedomestication of plantsand animals and the emergence of the written word provided evidence for the passing of systematic knowledge and culture from one generation to the next.[6]

Plant lore and plant selection

[edit]

During the Neolithic Revolution, plant knowledge increased most obviously through the use of plants for food and medicine. All of today'sstaple foodswere domesticated inprehistorictimes as a gradual process of selection of higher-yielding varieties took place, possibly unknowingly, over hundreds to thousands of years.Legumeswere cultivated on all continents but cereals made up most of the regular diet:ricein East Asia,wheatandbarleyin the Middle east, andmaizein Central and South America. By Greco-Roman times, popular food plants of today, includinggrapes,apples,figs,andolives,were being listed as named varieties in early manuscripts.[7]Botanical authorityWilliam Stearnhas observed that "cultivated plants are mankind's most vital and precious heritage from remote antiquity".[8]

It is also from the Neolithic, in about 3000 BC, that we glimpse the first known illustrations of plants[9]and read descriptions of impressive gardens in Egypt.[10]However protobotany, the first pre-scientific written record of plants, did not begin with food; it was born out of the medicinal literature ofEgypt,China,MesopotamiaandIndia.[11]Botanical historian Alan Morton notes that agriculture was the occupation of the poor and uneducated, while medicine was the realm of socially influentialshamans,priests,apothecaries,magiciansandphysicians,who were more likely to record their knowledge for posterity.[12]

Early botany

[edit]Ancient India

[edit]This articlerelies largely or entirely on asingle source.(May 2024) |

Early Indian texts, like theVedasmention plants with magical properties. TheSushruta Samhita,describes over 700 plants used for medicinal purposes. This text reflects a level of medical knowledge and practice comparable toancient Egypt.Notably, the Sushruta Samhita categorizes food plants based on their utilized parts, taste, and dietary effects. While lacking detailed botanical descriptions beyond occasional habitat or foliage references, the text demonstrates close observation of plants. This is evident in the classification of sugarcane varieties and the listing of fungi based on their growth medium. Interestingly, theCharaka Samhitā,foundational Ayurvedic text, presents the earliest known plant classification system in India, using habitat, presence of flowers/fruits, and reproduction as criteria.[13]

Classical antiquity

[edit]Classical Greece

[edit]

Ancient Athens, of the 6th century BC, was the busy trade centre at the confluence ofEgyptian,MesopotamianandMinoancultures at the height of Greek colonisation of the Mediterranean. The philosophical thought of this period ranged freely through many subjects.Empedocles(490–430 BC) foreshadowed Darwinian evolutionary theory in a crude formulation of the mutability of species andnatural selection.[14]The physicianHippocrates(460–370 BC) avoided the prevailing superstition of his day and approached healing by close observation and the test of experience. At this time, a genuine non-anthropocentriccuriosity about plants emerged. The major works written about plants extended beyond the description of their medicinal uses to the topics of plant geography, morphology, physiology, nutrition, growth and reproduction.[15]

Theophrastus and the origin of botanical science

[edit]

Foremost among the scholars studying botany wasTheophrastusof Eressus (Greek:Θεόφραστος;c. 371–287 BC) who has been frequently referred to as the "Father of Botany". He was a student and close friend ofAristotle(384–322 BC) and succeeded him as head of theLyceum(an educational establishment like a modern university) in Athens with its tradition ofperipateticphilosophy. Aristotle's special treatise on plants —θεωρία περὶ φυτῶν— is now lost, although there are many botanical observations scattered throughout his other writings (these have been assembled byChristian WimmerinPhytologiae Aristotelicae Fragmenta,1836) but they give little insight into his botanical thinking.[16]The Lyceum prided itself in a tradition of systematic observation of causal connections, critical experiment and rational theorizing. Theophrastus challenged the superstitious medicine employed by the physicians of his day, called rhizotomi, and also the control over medicine exerted by priestly authority and tradition.[17]Together with Aristotle, he had tutoredAlexander the Greatwhose military conquests were carried out with all the scientific resources of the day, the Lyceum garden probably containing many botanical trophies collected during his campaigns as well as other explorations in distant lands.[18]It was in this garden where he gained much of his plant knowledge.[19]

Enquiry into PlantsandCauses of Plants

[edit]

Theophrastus's major botanical works were theEnquiry into Plants(Historia Plantarum) andCauses of Plants(Causae Plantarum) which were his lecture notes for the Lyceum.[20]The opening sentence of theEnquiryreads like a botanicalmanifesto:

We must consider the distinctive characters and the general nature of plants from the point of view of their morphology, their behaviour under external conditions, their mode of generation and the whole course of their life.

— Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants

TheEnquiryis 9 books of "applied" botany dealing with the forms andclassificationof plants andeconomic botany,examining the techniques ofagriculture(relationship of crops to soil, climate, water and habitat) andhorticulture.He described some 500 plants in detail, often including descriptions of habitat and geographic distribution, and he recognised some plant groups that can be recognised as modern-day plant families. Some names he used, likeCrataegus,DaucusandAsparagushave persisted until today. His second bookCauses of Plantscovers plant growth and reproduction (akin to modern physiology).[21]Like Aristotle, he grouped plants into "trees", "undershrubs", "shrubs" and "herbs" but he also made several other important botanical distinctions and observations. He noted that plants could beannuals,perennialsandbiennials,they were also eithermonocotyledonsordicotyledonsand he also noticed the difference betweendeterminateand indeterminate growth and details of floral structure including the degree of fusion of the petals, position of the ovary and more.[22][23]These lecture notes of Theophrastus comprise the first clear exposition of the rudiments of plant anatomy, physiology, morphology and ecology — presented in a way that would not be matched for another eighteen centuries.[24]

Pedanius Dioscorides

[edit]

A full synthesis of ancient Greek pharmacology was compiled inDeMateria Medicac. 60 AD byPedanius Dioscorides(c. 40-90 AD) who was a Greek physician with the Roman army. This work proved to be the definitive text on medicinal herbs, both oriental and occidental, for fifteen hundred years until the dawn of the EuropeanRenaissancebeing slavishly copied again and again throughout this period.[25]Though rich in medicinal information with descriptions of about 600 medicinal herbs, the botanical content of the work was extremely limited.[26]

Ancient Rome

[edit]

The Romans contributed little to the foundations of botanical science laid by the ancient Greeks, but made a sound contribution to our knowledge of applied botany as agriculture. In works titledDe Re Rustica,four Roman writers contributed to a compendiumScriptores Rei Rusticae,published from the Renaissance on, which set out the principles and practice of agriculture. These authors wereCato(234–149 BC),Varro(116–27 BC) and, in particular,Columella(4–70 AD) andPalladius(4th century AD).[27]

Pliny the Elder

[edit]Roman encyclopaedistPliny the Elder(23–79 AD) deals with plants in Books 12 to 26 of his 37-volume highly influential workNaturalis Historiain which he frequently quotes Theophrastus but with a lack of botanical insight although he does, nevertheless, draw a distinction between true botany on the one hand, and farming and medicine on the other.[28]It is estimated that at the time of the Roman Empire between 1300 and 1400 plants had been recorded in the West.[29]

Ancient China

[edit]Inancient China,lists of different plants and herb concoctions forpharmaceuticalpurposes date back to at least the time of theWarring States(481 BC-221 BC). Many Chinese writers over the centuries contributed to the written knowledge of herbal pharmaceutics. The Chinese dictionary-encyclopaediaErh Yaprobably dates from about 300 BC and describes about 334 plants classed as trees or shrubs, each with a common name and illustration. TheHan Dynasty(202 BC-220 AD) includes the notable work of theHuangdi Neijingand the famous pharmacologistZhang Zhongjing.

Medieval knowledge

[edit]Medicinal plants of the early Middle Ages

[edit]

In Western Europe, after Theophrastus, botany passed through a bleak period of 1800 years when little progress was made and, indeed, many of the early insights were lost. As Europe entered theMiddle Ages(5th to 15th centuries), China, India and the Arab world enjoyed a golden age.

Medieval China

[edit]Chinese philosophy had followed a similar path to that of the ancient Greeks. Between 100 and 1700 AD, many new works on pharmaceutical botany were produced. The 11th century scientists and statesmenSu SongandShen Kuocompiled learned treatises on natural history, emphasising herbal medicine.[30]Among the pharmaceutical botany works were encyclopaedic accounts and treatises compiled for the Chinese imperial court. These were free of superstition and myth with carefully researched descriptions and nomenclature; they included cultivation information and notes on economic and medicinal uses — and even elaborate monographs on ornamental plants. But there was no experimental method and no analysis of the plant sexual system, nutrition, or anatomy.[31]

Medieval India

[edit]In India, simple artificial plant classification became more botanical with the work ofParashara(c. 400 – c. 500 AD), the author ofVṛksayurveda(the science of life of trees).[32]He made close observations of cells and leaves and divided plants into Dvimatrka (Dicotyledons) and Ekamatrka (Monocotyledons). He has developed a more elaborate classification based largely on morphological consideration such as floral characters, their resemblances and differences into groupings (ganas) akin to modern floral families:Samiganiya(Fabaceae),Puplikagalniya(Rutaceae),Svastikaganiya(Cruciferae),Tripuspaganiya(Cucurbitaceae),Mallikaganiya(Apocynaceae), andKurcapuspaganiya(Asteraceae).[33][verification needed][34]Important medieval Indian works of plant physiology include thePrthviniraparyamofUdayana,Nyayavindutikaof Dharmottara,Saddarsana-samuccayaof Gunaratna, andUpaskaraof Sankaramisra.[citation needed]

Islamic Golden Age

[edit]

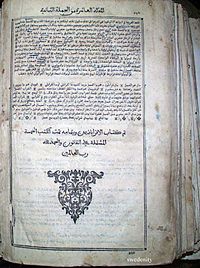

The 400-year period from the 9th to 13th centuries AD was theIslamic Renaissance,a time when Islamic culture and science thrived. Greco-Roman texts were preserved, copied and extended although new texts always emphasised the medicinal aspects of plants.KurdishbiologistĀbu Ḥanīfah Āḥmad ibn Dawūd Dīnawarī(828–896 AD) is known as the founder of Arabic botany; hisKitâb al-nabât('Book of Plants') describes 637 species, discussing plant development from germination to senescence and including details of flowers and fruits.[35]TheMutazilitephilosopherand physicianIbn Sina(Avicenna) (c. 980–1037 AD) was another influential figure, hisThe Canon of Medicinebeing a landmark in the history of medicine treasured until theEnlightenment.[36]

The Silk Road

[edit]Following thefall of Constantinople(1453), the newly expandedOttoman Empirewelcomed European embassies in its capital, which in turn became the sources of plants from those regions to the east which traded with the empire. In the following century, twenty times as many plants entered Europe along theSilk Roadas had been transported in the previous two thousand years, mainly as bulbs. Others were acquired primarily for their alleged medicinal value. Initially, Italy benefited from this new knowledge, especiallyVenice,which traded extensively with the East. From there, these new plants rapidly spread to the rest of Western Europe.[37]By the middle of the sixteenth century, there was already a flourishing export trade of various bulbs from Turkey to Europe.[38]

The Age of Herbals

[edit]

In the EuropeanMiddle Agesof the 15th and 16th centuries, the lives of European citizens were based around agriculture but when printing arrived, with movable type andwoodcutillustrations, it was not treatises on agriculture that were published, but lists of medicinal plants with descriptions of their properties or "virtues". These first plant books, known asherbalsshowed that botany was still a part of medicine, as it had been for most of ancient history.[36]Authors of herbals were often curators of university gardens,[39]and most herbals were derivative compilations of classic texts, especiallyDe Materia Medica.

The authors of the oldest herbals of the 16th century, Brunfels, Fuchs, Bock, Mattioli and others, regarded plants mainly as the vehicles of medicinal virtues.... Their chief object was to discover the plants employed by the physicians of antiquity, the knowledge of which had been lost in later times. The corrupt texts of Theophrastus, Dioscorides, Pliny and Galen had been in many respects improved and illustrated by... Italian commentators of the 15th and... early part of the 16th century; but there was one imperfection which no criticism could remove,—the highly unsatisfactory descriptions of the old authors or the entire absence of descriptions.[40]

It was moreover at first assumed that the plants described by the Greek physicians must grow wild in Germany also, and generally in the rest of Europe; each author identified a different native plant with some one mentioned by Dioscorides or Theophrastus or others, and thus there arose [in] the 16th century a confusion of nomenclature.[40]

However, the need for accurate and detailed plant descriptions meant that some herbals were more botanical than medicinal.

A great advance was made by the first German composers of herbals, who went straight to nature, described the wild plants growing around them and had figures of them carefully executed in wood. Thus was made the first beginning of a really scientific examination of plants, though the aims pursued were not yet truly scientific, for no questions were proposed as to the nature of plants, their organisation or mutual relations; the only point of interest was the knowledge of individual forms and of their medicinal virtues.[41]

— Julius von Sachs, History of Botany

GermanOtto Brunfels's (1464–1534)Herbarum Vivae Icones(1530) contained descriptions of about 47 species new to science combined with accurate illustrations. His fellow countrymanHieronymus Bock's (1498–1554)Kreutterbuchof 1539 described plants he found in nearby woods and fields and these were illustrated in the 1546 edition.[42]However, it wasValerius Cordus(1515–1544) who pioneered the formal botanical description that detailed both flowers and fruits, some anatomy including the number of chambers in theovary,and the type ofovuleplacentation.He also made observations on pollen and distinguished betweeninflorescencetypes.[42]His five-volumeHistoria Plantarumwas published about 18 years after his early death aged 29 in 1561–1563. In England,William Turner(1515–1568) in hisLibellus De Re Herbaria Novus(1538) published names, descriptions and localities of many native British plants[43]and in HollandRembert Dodoens(1517–1585), inStirpium Historiae(1583), included descriptions of many new species from the Netherlands in a scientific arrangement.[44]

Herbals contributed to botany by setting in train the science of plant description, classification, and botanical illustration. Up to the 17th century, botany and medicine were one and the same but those books emphasising medicinal aspects eventually omitted the plant lore to become modern pharmacopoeias; those that omitted the medicine became more botanical and evolved into the modern compilations of plant descriptions we callFloras.These were often backed by specimens deposited in aherbariumwhich was a collection of dried plants that verified the plant descriptions given in the Floras. The transition from herbal to Flora marked the final separation of botany from medicine.[45]

The Renaissance and Age of Enlightenment (1550–1800)

[edit]

The revival of learning during the EuropeanRenaissancerenewed interest in plants. The church, feudal aristocracy and an increasingly influential merchant class that supported science and the arts, now jostled in a world of increasing trade. Sea voyages of exploration returned botanical treasures to the large public, private, and newly established botanic gardens, and introduced an eager population to novel crops, drugs and spices from Asia, theEast Indiesand theNew World.

The number of scientific publications increased. In England, for example, scientific communication and causes were facilitated by learned societies like Royal Society (founded in 1660) and theLinnaean Society(founded in 1788): there was also the support and activities of botanical institutions like theJardin du Roiin Paris,Chelsea Physic Garden,Royal Botanic Gardens Kew,and theOxfordandCambridge Botanic Gardens,as well as the influence of renowned private gardens and wealthy entrepreneurial nurserymen.[46]By the early 17th century the number of plants described in Europe had risen to about 6000.[47]The 18th centuryEnlightenmentvalues of reason and science coupled with new voyages to distant lands instigating another phase of encyclopaedic plant identification, nomenclature, description and illustration, "flower painting" possibly at its best in this period of history.[48][49]Plant trophies from distant lands decorated the gardens of Europe's powerful and wealthy in a period of enthusiasm for natural history, especially botany (a preoccupation sometimes referred to as "botanophilia" ) that is never likely to recur.[50]Often such exotic new plant imports (primarily from Turkey), when they first appeared in print in English, lacked common names in the language.[49]

During the 18th century, botany was one of the few sciences considered appropriate for genteel educated women. Around 1760, with the popularization of the Linnaean system, botany became much more widespread among educated women who painted plants, attended classes on plant classification, and collected herbarium specimens although emphasis was on the healing properties of plants rather than plant reproduction which had overtones of sexuality. Women began publishing on botanical topics and children's books on botany appeared by authors likeCharlotte Turner Smith.Cultural authorities argued that education through botany created culturally and scientifically aware citizens, part of the thrust for 'improvement' that characterised the Enlightenment. However, in the early 19th century with the recognition of botany as an official science, women were again excluded from the discipline.[51]Compared to other sciences, however, in botany the number of female researchers, collectors, or illustrators has always been remarkably high.[52]

Botanical gardens and herbaria

[edit]

Public and private gardens have always been strongly associated with the historical unfolding of botanical science.[53] Early botanical gardens were physic gardens, repositories for the medicinal plants described in the herbals. As they were generally associated with universities or other academic institutions, the plants were also used for study. The directors of these gardens were eminent physicians with an educational role as "scientific gardeners" and it was staff of these institutions that produced many of the published herbals.

The botanical gardens of the modern tradition were established in northern Italy, the first being atPisa(1544), founded byLuca Ghini(1490–1556). Although part of a medical faculty, the first chair ofmateria medica,essentially a chair in botany, was established in Padua in 1533. Then in 1534, Ghini became Reader inmateria medicaat Bologna University, whereUlisse Aldrovandiestablished a similar garden in 1568 (see below).[54]Collections of pressed and dried specimens were called ahortus siccus(garden of dry plants) and the first accumulation of plants in this way (including the use of a plant press) is attributed to Ghini.[55][56]Buildings calledherbariahoused these specimens mounted on card with descriptive labels. Stored in cupboards in systematic order, they could be preserved in perpetuity and easily transferred or exchanged with other institutions, a taxonomic procedure that is still used today.

By the 18th century, the physic gardens had been transformed into "order beds" that demonstrated the classification systems that were being devised by botanists of the day — but they also had to accommodate the influx of curious, beautiful and new plants pouring in from voyages of exploration that were associated with European colonial expansion.

From Herbal to Flora

[edit]Plant classification systems of the 17th and 18th centuries now related plants to one another and not to man, marking a return to the non-anthropocentric botanical science promoted by Theophrastus over 1500 years before. In England, various herbals in eitherLatinor English were mainly compilations and translations of continental European works, of limited relevance to the British Isles. This included the rather unreliable work ofGerard(1597).[57]The first systematic attempt to collect information on British plants was that ofThomas Johnson(1629),[58][59]who was later to issue his own revision of Gerard's work (1633–1636).[60]

However, Johnson was not the first apothecary or physician to organise botanical expeditions tosystematisetheir local flora. In Italy,Ulisse Aldrovandi(1522 – 1605) organised an expedition to theSibylline mountainsinUmbriain 1557, and compiled a localFlora.He then began to disseminate his findings amongst other European scholars, forming an early network ofknowledge sharing"molti amici in molti luoghi"(many friends in many places),[61][62]including Charles de l'Écluse (Clusius) (1526 – 1609) atMontpellierand Jean de Brancion atMalines.Between them, they started developing Latin names for plants, in addition to their common names.[63]The exchange of information and specimens between scholars was often associated with the founding ofbotanical gardens(above), and to this end Aldrovandi founded one of the earliest at his university inBologna,theOrto Botanico di Bolognain 1568.[54]

In France, Clusius journeyed throughout most ofWestern Europe,making discoveries in the vegetable kingdom along the way. He compiled Flora of Spain (1576), and Austria and Hungary (1583). He was the first to propose dividing plants into classes.[64][65]Meanwhile, in Switzerland, from 1554,Conrad Gessner(1516 – 1565) made regular explorations of theSwiss Alpsfrom his nativeZurichand discovered many new plants. He proposed that there were groups or genera of plants. He said that each genus was composed of many species and that these were defined by similar flowers and fruits. This principle of organization laid the groundwork for future botanists. He wrote his importantHistoria Plantarumshortly before his death. At Malines, inFlandershe established and maintained the botanical gardens of Jean de Brancion from 1568 to 1573, and first encounteredtulips.[66][67]

This approach coupled with the new Linnaean system ofbinomial nomenclatureresulted in plant encyclopaedias without medicinal information calledFlorasthat meticulously described and illustrated the plants growing in particular regions.[68]The 17th century also marked the beginning of experimental botany and application of a rigorous scientific method, while improvements in the microscope launched the new discipline of plant anatomy whose foundations, laid by the careful observations of EnglishmanNehemiah Grew[69]and ItalianMarcello Malpighi,would last for 150 years.[70]

Botanical exploration

[edit]More new lands were opening up to European colonial powers, the botanical riches being returned to European botanists for description. This was a romantic era of botanical explorers, intrepidplant huntersand gardener-botanists. Significant botanical collections came from: the West Indies (Hans Sloane(1660–1753)); China (James Cunningham); the spice islands of the East Indies (Moluccas,George Rumphius(1627–1702)); China and Mozambique (João de Loureiro(1717–1791)); West Africa (Michel Adanson(1727–1806)) who devised his own classification scheme and forwarded a crude theory of the mutability of species; Canada, Hebrides, Iceland, New Zealand byCaptain James Cook's chief botanistJoseph Banks(1743–1820).[71]

Classification and morphology

[edit]

By the middle of the 18th century, the botanical booty resulting from the era of exploration was accumulating in gardens and herbaria – and it needed to be systematically catalogued. This was the task of the taxonomists, the plant classifiers.

Plant classifications have changed over time from "artificial" systems based on general habit and form, to pre-evolutionary "natural" systems expressing similarity using one to many characters, leading to post-evolutionary "natural" systems that use characters to inferevolutionary relationships.[72]

Italian physicianAndrea Caesalpino(1519–1603) studied medicine and taught botany at theUniversity of Pisafor about 40 years eventually becoming Director of theBotanic Garden of Pisafrom 1554 to 1558. His sixteen-volumeDe Plantis(1583) described 1500 plants and hisherbariumof 260 pages and 768 mounted specimens still remains. Caesalpino proposed classes based largely on the detailed structure of the flowers and fruit;[65]he also applied the concept of the genus.[73]He was the first to try and derive principles of natural classification reflecting the overall similarities between plants and he produced a classification scheme well in advance of its day.[74]Gaspard Bauhin(1560–1624) produced two influential publicationsProdromus Theatrici Botanici(1620) andPinax(1623). These brought order to the 6000 species now described and in the latter he used binomials and synonyms that may well have influenced Linnaeus's thinking. He also insisted that taxonomy should be based on natural affinities.[75]

To sharpen the precision of description and classification,Joachim Jung(1587–1657) compiled a much-needed botanical terminology which has stood the test of time. English botanistJohn Ray(1623–1705) built on Jung's work to establish the most elaborate and insightful classification system of the day.[76]His observations started with the local plants of Cambridge where he lived, with theCatalogus Stirpium circa Cantabrigiam Nascentium(1860) which later expanded to hisSynopsis Methodica Stirpium Britannicarum,essentially the first British Flora. Although hisHistoria Plantarum(1682, 1688, 1704) provided a step towards a world Flora as he included more and more plants from his travels, first on the continent and then beyond. He extended Caesalpino's natural system with a more precise definition of the higher classification levels, deriving many modern families in the process, and asserted that all parts of plants were important in classification. He recognised that variation arises from both internal (genotypic) and external environmental (phenotypic) causes and that only the former was of taxonomic significance. He was also among the first experimental physiologists. TheHistoria Plantarumcan be regarded as the first botanical synthesis and textbook for modern botany. According to botanical historian Alan Morton, Ray "influenced both the theory and the practice of botany more decisively than any other single person in the latter half of the seventeenth century".[77]Ray's family system was later extended byPierre Magnol(1638–1715) andJoseph de Tournefort(1656–1708), a student of Magnol, achieved notoriety for his botanical expeditions, his emphasis on floral characters in classification, and for reviving the idea of the genus as the basic unit of classification.[78]

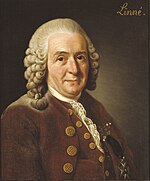

Above all it was SwedishCarl Linnaeus(1707–1778), who eased the task of plant cataloguing. He adopted a sexual system of classification using stamens and pistils as important characters. Among his most important publications wereSystema Naturae(1735),Genera Plantarum(1737), andPhilosophia Botanica(1751) but it was in hisSpecies Plantarum(1753) that he gave every species abinomialthus setting the path for the future accepted method of designating the names of all organisms. Linnaean thought and books dominated the world of taxonomy for nearly a century.[79]His sexual system was later elaborated byBernard de Jussieu(1699–1777) whose nephewAntoine-Laurent de Jussieu(1748–1836) extended it yet again to include about 100 orders (present-day families).[80]FrenchmanMichel Adanson(1727–1806) in hisFamilles des Plantes(1763, 1764), apart from extending the current system of family names, emphasized that a natural classification must be based on a consideration of all characters, even though these may later be given different emphasis according to their diagnostic value for the particular plant group. Adanson's method has, in essence, been followed to this day.[81]

18th century plant taxonomy bequeathed to the 19th century a precise binomial nomenclature and botanical terminology, a system of classification based on natural affinities, and a clear idea of the ranks of family, genus and species — although the taxa to be placed within these ranks remains, as always, the subject of taxonomic research.

Anatomy

[edit]

In the first half of the 18th century, botany was beginning to move beyond descriptive science into experimental science. Although themicroscopewas invented in 1590, it was only in the late 17th century that lens grinding provided the resolution needed to make major discoveries.Antony van Leeuwenhoekis a notable example of an early lens grinder who achieved remarkable resolution with his single-lens microscopes. Important general biological observations were made byRobert Hooke(1635–1703) but the foundations of plant anatomy were laid by ItalianMarcello Malpighi(1628–1694) of the University of Bologna in hisAnatome Plantarum(1675) and Royal Society EnglishmanNehemiah Grew(1628–1711) in hisThe Anatomy of Plants Begun(1671) andAnatomy of Plants(1682). These botanists explored what is now called developmental anatomy and morphology by carefully observing, describing and drawing the developmental transition from seed to mature plant, recording stem and wood formation. This work included the discovery and naming ofparenchymaandstomata.[82]

Physiology

[edit]In plant physiology, research interest was focused on the movement of sap and the absorption of substances through the roots.Jan Helmont(1577–1644) by experimental observation and calculation, noted that the increase in weight of a growing plant cannot be derived purely from the soil, and concluded it must relate to water uptake.[83]EnglishmanStephen Hales[84](1677–1761) established by quantitative experiment that there is uptake of water by plants and a loss of water by transpiration and that this is influenced by environmental conditions: he distinguished "root pressure", "leaf suction" and "imbibition" and also noted that the major direction of sap flow in woody tissue is upward. His results were published inVegetable Staticks(1727) He also noted that "air makes a very considerable part of the substance of vegetables".[85]English chemistJoseph Priestley(1733–1804) is noted for his discovery of oxygen (as now called) and its production by plants. Later,Jan Ingenhousz(1730–1799) observed that only in sunlight do the green parts of plants absorb air and release oxygen, this being more rapid in bright sunlight while, at night, the air (CO2) is released from all parts. His results were published inExperiments upon vegetables(1779) and with this the foundations for 20th century studies of carbon fixation were laid. From his observations, he sketched the cycle of carbon in nature even though the composition of carbon dioxide was yet to be resolved.[86]Studies in plant nutrition had also progressed. In 1804,Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure's (1767–1845)Recherches Chimiques sur la Végétationwas an exemplary study of scientific exactitude that demonstrated the similarity of respiration in both plants and animals, that the fixation of carbon dioxide includes water, and that just minute amounts of salts and nutrients (which he analyzed in chemical detail from plant ash) have a powerful influence on plant growth.[87]

Plant sexuality

[edit]

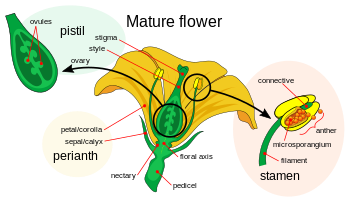

It wasRudolf Camerarius(1665–1721) who was the first to establish plant sexuality conclusively by experiment. He declared in a letter to a colleague, dated 1694 and titledDe Sexu Plantarum Epistola,that "no ovules of plants could ever develop into seeds from the female style and ovary without first being prepared by the pollen from the stamens, the male sexual organs of the plant".[88]

Some time later, the German academic and natural historianJoseph Kölreuter(1733–1806) extended this work by noting the function of nectar in attracting pollinators and the role of wind and insects in pollination. He also produced deliberate hybrids, observed the microscopic structure of pollen grains and how the transfer of matter from the pollen to the ovary inducing the formation of the embryo.[89]

One hundred years after Camerarius, in 1793,Christian Sprengel(1750–1816) broadened the understanding of flowers by describing the role of nectar guides in pollination, the adaptive floral mechanisms used for pollination, and the prevalence of cross-pollination, even though male and female parts are usually together on the same flower.[90]

Much was learned about plant sexuality by unravelling the reproductive mechanisms of mosses, liverworts and algae. In hisVergleichende Untersuchungenof 1851,Wilhelm Hofmeister(1824–1877) starting with the ferns and bryophytes demonstrated that the process of sexual reproduction in plants entails an "alternation of generations" betweensporophytesandgametophytes.[91]This initiated the new field ofcomparative morphologywhich, largely through the combined work ofWilliam Farlow(1844–1919),Nathanael Pringsheim(1823–1894),Frederick Bower,Eduard Strasburgerand others, established that an "alternation of generations" occurs throughout the plant kingdom.[92]

Nineteenth-century foundations of modern botany

[edit]In about the mid-19th century, scientific communication changed. Until this time, ideas were largely exchanged by reading the works of authoritative individuals who dominated in their field: these were often wealthy and influential "gentlemen scientists". Now, research was reported by the publication of "papers" that emanated from research "schools" that promoted the questioning of conventional wisdom. This process had started in the late 18th century when specialist journals began to appear.[93]Even so, botany was greatly stimulated by the appearance of the first "modern" textbook,Matthias Schleiden's (1804–1881)Grundzüge der Wissenschaftlichen Botanik,published in English in 1849 asPrinciples of Scientific Botany.[94]By 1850, an invigorated organic chemistry had revealed the structure of many plant constituents.[95]Although the great era of plant classification had now passed, the work of description continued.Augustin de Candolle(1778–1841) succeededAntoine-Laurent de Jussieuin managing the botanical projectProdromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis(1824–1841) which involved 35 authors: it contained all the dicotyledons known in his day, some 58000 species in 161 families, and he doubled the number of recognized plant families, the work being completed by his sonAlphonse(1806–1893) in the years from 1841 to 1873.[96]

Plant geography and ecology

[edit]

The opening of the 19th century was marked by an increase in interest in the connection between climate and plant distribution.Carl Willdenow(1765–1812) examined the connection between seed dispersal and distribution, the nature of plant associations and the impact of geological history. He noticed the similarities between the floras of N America and N Asia, the Cape and Australia, and he explored the ideas of "centre of diversity"and"centre of origin".GermanAlexander von Humboldt(1769–1859) and FrenchmanAime Bonpland(1773–1858) published a massive and highly influential 30 volume work on their travels;Robert Brown(1773–1852) noted the similarities between the floras of S Africa, Australia and India, whileJoakim Schouw(1789–1852) explored more deeply than anyone else the influence on plant distribution of temperature,soilfactors, especially soil water, and light, work that was continued byAlphonse de Candolle(1806–1893).[97]Joseph Hooker(1817–1911) pushed the boundaries of floristic studies with his work on Antarctica, India and the Middle East with special attention toendemism.August Grisebach(1814–1879) inDie Vegetation der Erde(1872) examinedphysiognomyin relation to climate and in America geographic studies were pioneered byAsa Gray(1810–1888).[98]

Physiological plant geography, orecology,emerged from floristic biogeography in the late 19th century as environmental influences on plants received greater recognition. Early work in this area was synthesised by Danish professorEugenius Warming(1841–1924) in his bookPlantesamfund(Ecology of Plants, generally taken to mark the beginning of modern ecology) including new ideas on plant communities, their adaptations and environmental influences. This was followed by another grand synthesis, thePflanzengeographie auf Physiologischer GrundlageofAndreas Schimper(1856–1901) in 1898 (published in English in 1903 as Plant-geography upon a physiological basis translated by W. R. Fischer, Oxford: Clarendon press, 839 pp).[99]

Anatomy

[edit]

During the 19th century, German scientists led the way towards a unitary theory of the structure and life-cycle of plants. Following improvements in the microscope at the end of the 18th century,Charles Mirbel(1776–1854) in 1802 published hisTraité d'Anatomie et de Physiologie VégétaleandJohann Moldenhawer(1766–1827) publishedBeyträge zur Anatomie der Pflanzen(1812) in which he describes techniques for separating cells from the middlelamella.He identifiedvascularandparenchymatoustissues, described vascular bundles, observed the cells in thecambium,and interpreted tree rings. He found thatstomatawere composed of pairs of cells, rather than a single cell with a hole.[100]

Anatomical studies on thestelewere consolidated byCarl Sanio(1832–1891), who described the secondary tissues andmeristemincludingcambiumand its action.Hugo von Mohl(1805–1872) summarized work in anatomy leading up to 1850 inDie Vegetabilische Zelle(1851) but this work was later eclipsed by the encyclopaedic comparative anatomy ofHeinrich Anton de Baryin 1877. An overview of knowledge of the stele in root and stem was completed byVan Tieghem(1839–1914) and of the meristem byCarl Nägeli(1817–1891). Studies had also begun on the origins of thecarpelandflowerthat continue to the present day.[101]

Water relations

[edit]The riddle of water andnutrienttransport through the plant remained. Physiologist Von Mohl explored solute transport and the theory of water uptake by the roots using the concepts of cohesion, transpirational pull, capillarity and root pressure.[95]German dominance in the field of experimental physiology, largely influenced byWilhelm KnopandJulius von Sachs,was underlined by the publication of the definitive textbook on plant physiology synthesising the work of this period, Sachs'Vorlesungen über Pflanzenphysiologieof 1882. There were, however, some advances elsewhere such as the early exploration ofgeotropism(the effect of gravity on growth) by Englishman Thomas Knight, and the discovery and naming ofosmosisby FrenchmanHenri Dutrochet(1776–1847).[102]The AmericanDennis Robert Hoagland(1884–1949) discovered the dependence of nutrientabsorptionandtranslocationby the plant onmetabolic energy.[103]

Cytology

[edit]The cell nucleus was discovered byRobert Brownin 1831. Demonstration of the cellular composition of all organisms, with each cell possessing all the characteristics of life, is attributed to the combined efforts of botanist Matthias Schleiden and zoologistTheodor Schwann(1810–1882) in the early 19th century, although Moldenhawer had already shown that plants were wholly cellular with each cell having its own wall andJulius von Sachshad shown the continuityprotoplasmbetweencell walls.[104]

From 1870 to 1880, it became clear that cell nuclei are never formed anew but always derived from the substance of another nucleus. In 1882, Flemming observed the longitudinal splitting ofchromosomesin the dividing nucleus and concluded that each daughter nucleus received half of each of the chromosomes of the mother nucleus: then by the early 20th century, it was found that the number of chromosomes in a given species is constant. With genetic continuity confirmed and the finding byEduard Strasburgerthat the nuclei of reproductive cells (in pollen and embryo) have a reducing division (halving of chromosomes, now known asmeiosis) the field of heredity was opened up. By 1926,Thomas Morganwas able to outline a theory of thegeneand its structure and function. The form and function of plastids received similar attention, the association with starch being noted at an early date.[105]With observation of the cellular structure of all organisms and the process of cell division and continuity of genetic material, the analysis of the structure of protoplasm and the cell wall as well as that ofplastidsandvacuoles– what is now known ascytology,orcell theorybecame firmly established.

Later, the cytological basis of the gene-chromosome theory ofheredityextended from about 1900–1944 and was initiated by the rediscovery ofGregor Mendel's (1822–1884) laws of plant heredity first published in 1866 inExperiments on Plant Hybridizationand based on cultivated pea,Pisum sativum:this heralded the opening up of plant genetics. The cytological basis for gene-chromosome theory was explored through the role ofpolyploidyandhybridizationinspeciationand it was becoming better understood that interbreeding populations were the unit of adaptive change in biology.[106]

Developmental morphology and evolution

[edit]Until the 1860s, it was believed that species had remained unchanged through time: each biological form was the result of an independent act of creation and therefore absolutely distinct and immutable. But the hard reality of geological formations and strange fossils needed scientific explanation.Charles Darwin'sOrigin of Species(1859) replaced the assumption of constancy with the theory of descent with modification.Phylogenybecame a new principle as "natural" classifications became classifications reflecting, not just similarities, but evolutionary relationships.Wilhelm Hofmeisterestablished that there was a similar pattern of organization in all plants expressed through thealternation of generationsand extensivehomologyof structures.[107]

German writerJohann Wolfgang von Goethe(1749–1832), apolymath,had interests and influence that extended into botany. InDie Metamorphose der Pflanzen(1790), he provided a theory of plant morphology (he coined the word "morphology" ) and he included within his concept of "metamorphosis" modification during evolution, thus linking comparative morphology with phylogeny. Though the botanical basis of his work has been challenged, there is no doubt that he prompted discussion and research on the origin and function of floral parts.[108]His theory probably stimulated the opposing views of German botanistsAlexander Braun(1805–1877) and Matthias Schleiden who applied the experimental method to the principles of growth and form that were later extended byAugustin de Candolle(1778–1841).[109]

Carbon fixation (photosynthesis)

[edit]

At the start of the 19th century, the idea that plants could synthesize almost all their tissues from atmospheric gases had not yet emerged. The energy component of photosynthesis, the capture and storage of the Sun'sradiant energyin carbon bonds (a process on which all life depends) was first elucidated in 1847 byMayer,but the details of how this was done would take many more years.[110]Chlorophyll was named in 1818 and its chemistry gradually determined, to be finally resolved in the early 20th century. The mechanism of photosynthesis remained a mystery until the mid-19th century when Sachs, in 1862, noted that starch was formed in green cells only in the presence of light, and in 1882, he confirmed carbohydrates as the starting point for all other organic compounds in plants.[111]The connection between the pigment chlorophyll and starch production was finally made in 1864 but tracing the precise biochemical pathway of starch formation did not begin until about 1915.

Nitrogen fixation

[edit]Significant discoveries relating to nitrogen assimilation and metabolism, includingammonification,nitrificationandnitrogen fixation(the uptake of atmospheric nitrogen bysymbioticsoil microorganisms) had to wait for advances in chemistry and bacteriology in the late 19th century and this was followed in the early 20th century by the elucidation ofproteinandamino-acidsynthesis and their role in plant metabolism. With this knowledge, it was then possible to outline the globalnitrogen cycle.[112]

Twentieth century

[edit]

20th century science grew out of the solid foundations laid by the breadth of vision and detailed experimental observations of the 19th century. A vastly increased research force was now rapidly extending the horizons of botanical knowledge at all levels of plant organization from molecules to global plant ecology. There was now an awareness of the unity of biological structure and function at the cellular and biochemical levels of organisation. Botanical advance was closely associated with advances in physics and chemistry with the greatest advances in the 20th century mainly relating to the penetration of molecular organization.[113]However, at the level of plant communities it would take until mid century to consolidate work on ecology andpopulation genetics.[114] By 1910, experiments using labelledisotopeswere being used to elucidate plant biochemical pathways, to open the line of research leading to gene technology. On a more practical level, research funding was now becoming available from agriculture and industry.

Molecules

[edit]In 1903,Chlorophyllsa and b were separated by thin layerchromatographythen, through the 1920s and 1930s, biochemists, notablyHans Krebs(1900–1981) andCarl(1896–1984) andGerty Cori(1896–1957) began tracing out the central metabolic pathways of life. Between the 1930s and 1950s, it was determined thatATP,located inmitochondria,was the source of cellular chemical energy and the constituent reactions ofphotosynthesiswere progressively revealed. Then, in 1944,DNAwas extracted for the first time.[115]Along with these revelations, there was the discovery of plant hormones or "growth substances", notablyauxins,(1934)gibberellins(1934) andcytokinins(1964)[116]and the effects ofphotoperiodism,the control of plant processes, especially flowering, by the relative lengths of day and night.[117]

Following the establishment of Mendel's laws, the gene-chromosome theory of heredity was confirmed by the work ofAugust Weismannwho identified chromosomes as the hereditary material. Also, in observing the halving of the chromosome number in germ cells he anticipated work to follow on the details ofmeiosis,the complex process of redistribution of hereditary material that occurs in the germ cells. In the 1920s and 1930s,population geneticscombined the theory of evolution withMendelian geneticsto produce themodern synthesis.By the mid-1960s, the molecular basis of metabolism and reproduction was firmly established through the new discipline ofmolecular biology.Genetic engineering,the insertion of genes into a host cell for cloning, began in the 1970s with the invention ofrecombinant DNAtechniques and its commercial applications applied to agricultural crops followed in the 1990s. There was now the potential to identify organisms by molecular "fingerprinting"and to estimate the times in the past when critical evolutionary changes had occurred through the use of"molecular clocks".

Computers, electron microscopes and evolution

[edit]

Increased experimental precision combined with vastly improved scientific instrumentation was opening up exciting new fields. In 1936,Alexander Oparin(1894–1980) demonstrated a possible mechanism for the synthesis of organic matter from inorganic molecules. In the 1960s, it was determined that the Earth's earliest life-forms treated as plants, thecyanobacteriaknown asstromatolites,dated back some 3.5 billion years.[118]

Mid-century transmission and scanning electron microscopy presented another level of resolution to the structure of matter, taking anatomy into the new world of "ultrastructure".[119]

New and revised "phylogenetic" classification systems of the plant kingdom were produced by several botanists, includingAugust Eichler.A massive 23 volumeDie natürlichen Pflanzenfamilienwas published byAdolf Engler&Karl Prantlover the period 1887 to 1915.Taxonomybased on gross morphology was now being supplemented by using characters revealed bypollen morphology,embryology,anatomy,cytology,serology,macromoleculesand more.[120]The introduction of computers facilitated the rapid analysis of large data sets used fornumerical taxonomy(also calledtaximetricsorphenetics). The emphasis on truly natural phylogenies spawned the disciplines ofcladisticsandphylogenetic systematics.The grand taxonomic synthesisAn Integrated System of Classification of Flowering Plants(1981) of AmericanArthur Cronquist(1919–1992) was superseded when, in 1998, theAngiosperm Phylogeny Grouppublished aphylogenyof flowering plants based on the analysis ofDNAsequences using the techniques of the newmolecular systematicswhich was resolving questions concerning the earliest evolutionary branches of theangiosperms(flowering plants). The exact relationship of fungi to plants had for some time been uncertain. Several lines of evidence pointed to fungi being different from plants, animals and bacteria – indeed, more closely related to animals than plants. In the 1980s-90s, molecular analysis revealed an evolutionary divergence of fungi from other organisms about 1 billion years ago – sufficient reason to erect a unique kingdom separate from plants.[121]

Biogeography and ecology

[edit]

The publication ofAlfred Wegener's (1880–1930) theory ofcontinental drift1912 gave additional impetus to comparative physiology and the study ofbiogeographywhile ecology in the 1930s contributed the important ideas of plant community,succession,community change, and energy flows.[122]From 1940 to 1950, ecology matured to become an independent discipline asEugene Odum(1913–2002) formulated many of the concepts ofecosystem ecology,emphasising relationships between groups of organisms (especially material and energy relationships) as key factors in the field. Building on the extensive earlier work of Alphonse de Candolle,Nikolai Vavilov(1887–1943) from 1914 to 1940 produced accounts of the geography, centres of origin, and evolutionary history of economic plants.[123]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Prasad, G. P. (Jan–Jun 2016). "Vŗkşăyurvĕda of Parăśara--an ancient treatise on plant science".Bulletin of the Indian Institute of History of Medicine (Hyderabad).36(1): 63–74.

- ^"βοτάνη - LSJ".LSJ.Internet Archive. 27 January 2021. Archived fromthe originalon 2021-01-27.Retrieved19 September2024.

- ^Morton 1981,p. 49

- ^Sachs 1890,p. v

- ^Walters 1981,p. 3

- ^Morton 1981,p. 2

- ^Stearn 1986.

- ^Stearn 1965,pp. 279–91, 322–41

- ^Reed 1942,p. 3

- ^Morton 1981,p. 5

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 7–29

- ^Morton 1981,p. 15

- ^Morton 1981,p. 12

- ^Morton 1981,p. 23

- ^Morton 1981,p. 25

- ^Vines inOliver 1913,p. 8

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 29–43

- ^Singer 1923,p. 98

- ^Reed 1942,p. 34

- ^Morton 1981,p. 42

- ^Reed 1942,p. 37

- ^Thanos 2005.

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 36–43

- ^Harvey-Gibson 1919,p. 9

- ^Singer 1923,p. 101

- ^Morton 1981,p. 68

- ^Morton 1981,p. 69

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 70–1

- ^Sengbusch 2004.

- ^Needham et al 1986.

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 58–64

- ^A Concise History of Science in India (Eds.) D. M. Bose, S. N. Sen and B.V. Subbarayappa.Indian National Science Academy. 1971-10-15. p. 388.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^Majumdar 1982,pp. 356–411

- ^A Concise History of Science in India (Eds.) D. M. Bose, S. N. Sen and B.V. Subbarayappa.Indian National Science Academy. 1971-10-15. p. 56.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^Fahd 1996,p. 815

- ^abMorton 1981,p. 82

- ^Pavord 2005,pp. 11–13

- ^Pavord 1999.

- ^Sachs 1890,p. 19

- ^abSachs 1890,p. 3.

- ^Sachs 1890,pp. 3–4.

- ^abReed 1942,p. 65

- ^Arber 1986,pp. 119–124

- ^Reed 1942,p. 68

- ^Arber inOliver 1913,pp. 146–246

- ^Henrey 1975,pp. 631–46

- ^Morton 1981,p. 145

- ^Buck 2017.

- ^abJacobson 2014.

- ^Williams 2001.

- ^Shteir 1996,Prologue.

- ^Women in Botany

- ^Spencer & Cross 2017,pp. 43–93

- ^abConan 2005,p. 96.

- ^Sachs 1890,p. 18

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 120–4

- ^Gerard 1597

- ^Johnson 1629

- ^Pavord 2005,pp. 5–10

- ^Johnson 1636

- ^Conan 2005,pp. 121, 123.

- ^Bethencourt & Egmond 2007.

- ^Pavord 2005,p. 16

- ^Helmsley & Poole 2004.

- ^abMeyer 1854–57

- ^Willes 2011,p. 76.

- ^Goldgar 2007,p. 34.

- ^Arber 1986,p. 270

- ^Arber inOliver 1913,pp. 44–64

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 178–80

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 110–1

- ^Woodland 1991,pp. 372–408

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 71–3

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 130–40

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 147–8

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 82–3

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 196–216

- ^Woodland 1991,pp. 372–375

- ^Stafleu 1971,p. 79

- ^Reed 1942,p. 102

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 301–11

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 88–9

- ^Reed 1942,p. 91

- ^Darwin inOliver 1913,pp. 65–83

- ^Morton 1981,p. 250

- ^Reed 1942,p. 107

- ^Morton 1981,p. 338

- ^Reed 1942,p. 96

- ^Reed 1942,p. 97

- ^Reed 1942,p. 98

- ^Reed 1942,p. 138

- ^Reed 1942,p. 140

- ^Reynolds Green 1909,p. 502

- ^Morton 1981,p. 377

- ^abMorton 1981,p. 388

- ^Morton 1981,p. 372

- ^Morton 1981,p. 364

- ^Morton 1981,p. 413

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 126–33

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 368–370

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 386–395

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 390–1

- ^Hoagland, D R; Hibbard, P L; Davis, A R (1926)."The influence of light, temperature, and other conditions on the ability ofNitellacells to concentrate halogens in the cell sap ".Journal of General Physiology.10(1): 121–126.doi:10.1085/jgp.10.1.121.PMC2140878.PMID19872303.

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 381–2

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 154–75

- ^Morton 1981,p. 453

- ^Reynolds Green 1909,pp. 7–10, 501

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 343–6

- ^Morton 1981,pp. 371–3

- ^Reed 1942,p. 207

- ^Reed 1942,p. 197

- ^Reed 1942,pp. 214–40

- ^Morton 1981,p. 448

- ^Morton 1981,p. 451

- ^Morton 1981,p. 460

- ^Morton 1981,p. 461

- ^Morton 1981,p. 464

- ^Morton 1981,p. 454

- ^Morton 1981,p. 459

- ^Morton 1981,p. 456

- ^Bruns 2006.

- ^Morton 1981,p. 457

- ^de Candolle 1885.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]History of science

[edit]- Harkness, Deborah E.(2007).The Jewel house of art and nature: Elizabethan London and the social foundations of the scientific revolution.New Haven:Yale University Press.ISBN9780300111965.(see alsoThe Jewel House)

- Huff, Toby (2003).The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-52994-5.

- Majumdar, G. P. (1982). "Studies in History of Science in India". In Chattopadhyaya, Debiprasad (ed.).The history of botany and allied sciences in India (c. 2000 B.C. to 100 A.D.).Asha Jyoti, New Delhi: Editorial Enterprise.

- Needham, Joseph& Lu, Gwei-Djen (2000). Sivin, Nathan (ed.).Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 6 Part 6 Medicine.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ogilvie, Brian W. (2006).The Science of Describing Natural History in Renaissance Europe.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN9780226620862.

- Stafleu, Frans A. (1971).Linnaeus and the Linnaeans.Utrecht: International Association of Plant Taxonomy.ISBN978-90-6046-064-1.

History of botany, agriculture and horticulture

[edit]- Arber, Agnes(1986) [1912; 2nd ed. 1938].Stearn, William T.(ed.).Herbals: their origin and evolution. A chapter in the history of botany, 1470-1670(3rd ed.). Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521338790.

- Conan, Michel, ed. (2005).Baroque garden cultures: emulation, sublimation, subversion.Washington, D.C.:Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.ISBN978-0-88402-304-3.Retrieved21 February2015.

- Erichsen-Brown, Charlotte (1979).Medicinal and Other Uses of North American Plants: A Historical Survey with Special Reference to the Eastern Indian Tribes.Courier Corporation.ISBN978-0-486-25951-2.

- Ewan, Joseph; Arnold, Chester Arthur (1969).A short history of botany in the United States.Hafner Publishing Co.ISBN9780028443607.

- Fahd, Toufic (1996). "Botany and agriculture". In Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (eds.).Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science.Vol. 3. London: Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-12410-2.

- Fischer, Hubertus; Remmert, Volker R.; Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (2016).Gardens, Knowledge and the Sciences in the Early Modern Period.Birkhäuser.ISBN978-3-319-26342-7.

- Fries, Robert Elias(1950).A short history of botany in Sweden.Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells boktr. OCLC3954193

- Greene, Edward Lee(1983a). Egerton, Frank N. (ed.).Landmarks of Botanical History: Part 1.Stanford: Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-1075-6.;originally published asGreene, Edward L.(1909).Landmarks of Botanical History 1. Prior to 1562 A.D.Washington: Smithsonian Institution.OCLC174698401.

- Greene, Edward Lee(1983b). Egerton, Frank N. (ed.).Landmarks of Botanical History: Part 2.Stanford: Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-1075-6.

- Harvey-Gibson, Robert J. (1919).Outlines of the history of botany.London: A. & C. Black.ISBN9788171415083.Retrieved29 April2015.1999 reprint Google Books

- Helmsley, Alan R.; Poole, Imogen, eds. (2004).The Evolution of Plant Physiology: From Whole Plants to Ecosystems.London: Elsevier Academic Press.ISBN978-0-12-339552-8.

- Henrey, Blanche(1975).British botanical and horticultural literature before 1800 (Vols 1–3).Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-211548-5.

- Jackson, Benjamin D. (1881).Guide to the Literature of Botany, Being a Classified Selection of Botanical Works.London: Longmans, Green.

- Jacobson, Miriam (2014).Barbarous Antiquity: Reorienting the Past in the Poetry of Early Modern England.University of Pennsylvania Press.p. 118.ISBN978-0-8122-9007-3.

- Morton, Alan G. (1981).History of Botanical Science: An Account of the Development of Botany from Ancient Times to the Present Day.London:Academic Press.ISBN978-0-12-508382-9.(availablehereatInternet Archive)

- Meyer, Ernst H.F.(1854–57).Geschichte der Botanik.Königsberg: Verlag de Gebrűder Bornträger.Retrieved2009-12-11.

Geschichte der Botanik Meyer.

- Needham, Joseph;Lu, Gwei-djen & Huang, Hsing-Tsung (1986).Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 6 Part 1 Botany.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rádl, Emanuel(1909–1913).Geschichte der biologischen Theorien in der Neuzeit(in German) (2nd ed.). Leipzig: Verlag von W. Engelmann.

- Rakow, Donald; Lee, Sharon, eds. (2013).Public garden management.Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.ISBN9780470904596.Retrieved21 February2015.

- Reed, Howard S. (1942).A Short History of the Plant Sciences.New York: Ronald Press.

- Reynolds Green, Joseph (1909).History of Botany 1860–1900.Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sachs, Julius von(1875).Geschichte der Botanik vom 16. Jahrhundert bis 1860.Munich: Oldenbourg.Retrieved13 December2015.

- Sachs, Julius von(1890) [1875].Geschichte der Botanik vom 16. Jahrhundert bis 1860[History of botany (1530-1860)]. translated by Henry E. F. Garnsey, revised by Isaac Bayley Balfour. Oxford:Oxford University Press.doi:10.5962/bhl.title.30585.Retrieved13 December2015.,see alsoHistory of botany (1530-1860)atGoogle Books

- Green, J Reynolds.A history of botany 1860-1900; being a continuation of Sachs History of botany, 1530-1860.Oxford: Oxford University Press.Retrieved13 December2015.

- Stace, Clive A.(1989) [1980].Plant taxonomy and biosystematics(2nd. ed.). Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521427852.Retrieved29 April2015.

- Vavilov, Nicolai I.(1992).Origin and Geography of Cultivated Plants.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-40427-3.

- Williams, Roger L. (2001).Botanophilia in Eighteenth-Century France: The Spirit of the Enlightenment.Springer Science & Business Media.ISBN978-0-7923-6886-1.

- Winterborne, Jeffrey (2005).Hydroponics: indoor horticulture.Guildford: Pukka Press.ISBN978-0-9550112-0-7.Retrieved2009-12-14.

- Woodland, Dennis W. (1991).Contemporary Plant Systematics.New Jersey: Prentice Hall.ISBN978-0-205-12182-3.

Antiquity

[edit]- Baumann, Hellmut (1993) [1986].Die griechische Pflanzenwelt in Mythos, Kunst und Literatur[The Greek Plant World in Myth, Art, and Literature]. trans. William Thomas Stearn, Eldwyth Ruth Stearn. Timber Press.ISBN9780881922318.

- Hardy, Gavin; Totelin, Laurence (2016).Ancient Botany.Abingdon:Routledge.ISBN9781134386796.

- Raven, J.E.(2000).Stearn, W.T.(ed.).Plants and plant lore in ancient Greece.Oxford: Leopard's Press.ISBN9780904920406.

- Thanos, Costas A. (2005)."The Geography of Theophrastus' Life and of his Botanical Writings (Περι Φυτων)"(PDF).In Karamanos, A.J.; Thanos C.A. (eds.).Biodiversity and Natural Heritage in the Aegean, Proceedings of the Conference 'Theophrastus 2000' (Eressos - Sigri, Lesbos, July 6–8, 2000).Athens: Fragoudis. pp. 23–45. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-06-03.Retrieved2009-11-11.

British botany

[edit]- Barlow, Horace Mallinson (1913)."Old English herbals 1525-1640".Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine.6(Sect Hist Med). London: John Bale, Sons & Danielsson: 108–49.doi:10.1177/003591571300601512.PMC2006232.PMID19977241.

- Grubb, Peter J;Snow, E Anne;Walters, S Max(2004).100 Years of Plant Sciences in Cambridge: 1904–2004.Department of Plant Sciences, Cambridge University.

- Gunther, Robert Theodore (1922).Early British botanists and their gardens, based on unpublished writings of Goodyer, Tradescant, and others.Oxford University Press.

- Hoeniger, F. David; Hoeniger, J. F. M. (1969).The Development of Natural History in Tudor England.MIT Press.ISBN978-0-918016-29-4.

- Hoeniger, F.D.; Hoeniger, J.F.M. (1969).The Growth of Natural History in Stuart England: From Gerard to the Royal Society.Charlottesville:Folger Books.ISBN978-0-918016-14-0.

- Oliver, Francis W.,ed. (1913).Makers of British Botany.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- Raven, Charles E.(1950) [1942].John Ray, naturalist: his life and works(2nd ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521310833.

- Raven, Charles E.(1947).English naturalists from Neckham to Ray: a study of the making if the modern world.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.ISBN9781108016346.

- Walters, Stuart M.(1981).The shaping of Cambridge botany: a short history of whole-plant botany in Cambridge from the time of Ray into the present century.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521237956.

- Willes, Margaret (2011).The making of the English gardener. Plants, Books and Inspiration, 1560-1660.New Haven:Yale University Press.ISBN9780300163827.

Cultural studies

[edit]- Bethencourt, Francisco; Egmond, Florike, eds. (2007).Cultural exchange in Early Modern Europe. Volume 3 Correspondence and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400-1700.Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.ISBN9780521845489.Retrieved21 February2015.

- Fara, Patricia(2003).Sex, Botany and Empire: The Story of Carl Linnaeus and Joseph Banks.Cambridge: Icon Books.ISBN9781840464443.Retrieved22 February2015.

- George, Sam (2007).Botany, sexuality, and women's writing 1760-1830: from modest shoot to forward plant.Manchester:Manchester University Press.ISBN9780719076978.Retrieved23 February2015.

- Goldgar, Anne (2007).Tulipmania: money, honor, and knowledge in the Dutch golden age.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.ISBN9780226301303.Retrieved21 February2015.

- Kelley, Theresa M. (2012).Clandestine marriage botany and Romantic culture.Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN9781421407609.Retrieved6 March2015.

- Page, Judith W.; Smith, Elise L. (2011).Women, literature, and the domesticated landscape: England's disciples of Flora, 1780-1870.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN9780521768658.Retrieved6 March2015.

- Pavord, Anna(1999).The Tulip.London:Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN978-0-7475-4296-4.

- Pavord, Anna(2005).The naming of names: the search for order in the world of plants.New York:Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN978-1-59691-071-3.

- Shteir, Ann B. (1996).Cultivating women, cultivating science: Flora's daughters and botany in England, 1760-1860.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN978-0-8018-6175-8.Retrieved18 February2015.

- Thomas, Vivian; Faircloth, Nicki (2014).Shakespeare's Plants and Gardens: A Dictionary.Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN978-1-4725-5858-9.

Botanical art and illustration

[edit]- Kusukawa, Sachiko (2012).Picturing the Book of Nature: Image, Text, and Argument in Sixteenth-Century Human Anatomy and Medical Botany.University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-46529-6.

- Lefèvre, Wolfgang; Renn, Jürgen; Schoepflin, Urs, eds. (2003).The Power of Images in Early Modern Science.Basel: Birkhäuser Basel.ISBN9783034880992.

- Tomasi, Lucia Tongiorgi; Hirschauer, Gretchen A. (2002).The flowering of Florence: botanical art for the Medici. 3 March-27 May(PDF)(Exhibition catalogue). Washington:National Gallery of Art.ISBN978-0-85331-857-6.

Historical sources

[edit]- Gerard, John (1597).The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes.London: John Norton.Retrieved26 November2014.

- Johnson, Thomas, ed. (1636).Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, gathered by John Gerarde.London: Adam Islip, Joice Norton and Richard Whitakers.Retrieved19 February2015.

- Johnson, Thomas(1629).Iter Plantarum Investigationis ergo susceptum a decem Sociis in Agrum Cantianum, anno Dom. 1629, Julii 13.London.

- Fuchs, Leonhart (1642).De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes.Basileae: In officina Isingriniana.Retrieved20 February2015.

- Pulteney, Richard (1790).Historical and biographical sketches of the progress of botany in England from its origin to the introduction of the Linnæan system.London: T. Cadell.

- Penny Cyclopedia(1828–1843).The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.London: Charles Knight.

- de Candolle, Alphonse(1885) [1882].Origine des Plantes Cultivées[Origin of Cultivated Plants] (in French). New York: Appleton.Retrieved19 February2015.

Bibliographic sources

[edit]- Johnston, Stanley H. (1992).The Cleveland Herbal, Botanical, and Horticultural Collections: A Descriptive Bibliography of Pre-1830 Works from the Libraries of the Holden Arboretum, the Cleveland Medical Library Association, and the Garden Center of Greater Cleveland.Kent State University Press.ISBN978-0-87338-433-9.

- Stafleu, Frans A.;Cowan, Richard S.(1976–1988).Taxonomic literature: a selective guide to botanical publications and collections with dates, commentaries and types. 7 vols. + VIII supplements(2nd ed.). Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema.ISBN9789031302246.

Articles

[edit]- Bruns, Tom (2006)."Evolutionary biology: a kingdom revised".Nature.443(7113): 758–61.Bibcode:2006Natur.443..758B.doi:10.1038/443758a.PMID17051197.S2CID648881.

- Denham, Tim; Haberle, SG; Lentfer, C; Fullagar, R; Field, J; Therin, M; Porch, N; Winsborough, B; et al. (2003)."Origins of Agriculture at Kuk Swamp in the Highlands of New Guinea".Science.301(5630): 189–193.doi:10.1126/science.1085255.PMID12817084.S2CID10644185.

- Johnson, Dale E. (1985)."Literature on the history of botany and botanic gardens 1730–1840: A bibliography"(PDF).Huntia.6(1): 1–121.PMID11620777.

- Singer, Charles(1923). "Herbals".The Edinburgh Review.237:95–112.

- Spencer, Roger;Cross, Rob (2017)."The origins of botanic gardens and their relation to plant science with special reference to horticultural botany and cultivated plant taxonomy".Muelleria.35:43–93.doi:10.5962/p.291985.S2CID251005623.

- Stearn, William T.(1965). "The Origin and Later Development of Cultivated Plants".Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society.90:279–291, 322–341.

- Stearn, William T.(1986). "Historical Survey of the Naming of Cultivated Plants".Acta Horticulturae.182:18–28.

- Vavilov, Nicolai I.(1951). "The Origin, Variation, Immunity and Breeding of Cultivated Plants".Chronica Botanica.13(6). trans. K. Starr Chester: 1–366.Bibcode:1951SoilS..72..482V.doi:10.1097/00010694-195112000-00018.

- Raven, John A.(April 2004). "Building botany in Cambridge. 1904–2004: the centenary of the opening of the Botany School, University of Cambridge, UK".New Phytologist.162(1): 7–8.doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01040.x.

- George, Sam (June 2005). "'Not Strictly Proper For A Female Pen': Eighteenth-Century Poetry and the Sexuality of Botany ".Comparative Critical Studies.2(2): 191–210.doi:10.3366/ccs.2005.2.2.191.

- Shteir, Ann B. (Spring 1990). "Botanical Dialogues: Maria Jacson and Women's Popular Science Writing in England".Eighteenth-Century Studies.23(3): 301–317.doi:10.2307/2738798.JSTOR2738798.

- Shteir, Ann B. (2007). "Flora primavera or Flora meretrix? Iconography, Gender, and Science".Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture.36(1): 147–168.doi:10.1353/sec.2007.0014.S2CID143804304.

- Williams, Roger L. (2011)."On the establishment of the principal gardens of botany: a bibliographical essay by Jean-Philippe-François Deleuze"(PDF).Huntia.14(2): 147–176.

Websites

[edit]- BSA."Evolution and Diversity".Botany for the Next Millennium: I. The intellectual: evolution, development, ecosystems.Retrieved19 February2015.

- Buck, Jutta (2017)."A Brief History of Botanical Art".American Society of Botanical Artists.Retrieved20 November2017.

- Sengbusch, Peter (2004)."Botany: The History of a Science".Botany online.Retrieved19 November2017.

- Tiwari, Lalit (24 June 2003)."Ancient Indian Botany and Taxonomy".The Infinity Foundation.Retrieved15 December2009.

- Widder, Agnes Haigh."Women and Botany in 18th and Early 19th-Century England".Michigan State University Libraries.

- National Library of Medicine

- North, Michael (14 April 2016)."Curious Herbals".The Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine.National Library of Medicine.Retrieved19 November2017.

- North, Michael (14 May 2015)."1. The Earliest Herbals".The Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine.National Library of Medicine.Retrieved19 November2017.

- North, Michael (9 July 2015)."2. Medieval Herbals in Movable Type".The Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine.National Library of Medicine.Retrieved19 November2017.

- North, Michael (29 September 2015)."3. A German Botanical Renaissance".The Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine.National Library of Medicine.Retrieved19 November2017.