Kalmar Union

Kalmar Union Kalmarunionen | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1397–1523 | |||||||||||||||

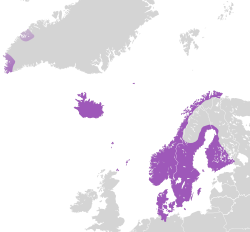

The Kalmar Union,c. 1400 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Personal union | ||||||||||||||

| Capital |

55°40′N12°34′E/ 55.667°N 12.567°E | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Personal union | ||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||

• 1397–1442a | Eric of Pomerania(first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1513–23b | Christian II(last) | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | RiksrådandHerredag (one in each kingdom) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||

• Inception | 17 June 1397 | ||||||||||||||

| 1434–1436 | |||||||||||||||

| November 1520 | |||||||||||||||

•Gustav Vasaelected as King of Sweden | 1523 | ||||||||||||||

•Denmark-Norwaywas established. | 1523 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

• Total | 2,839,386 km2(1,096,293 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Mark,Örtug,Norwegian penning,Swedish penning | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Part ofa serieson |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

TheKalmar Union[a]was apersonal unioninScandinavia,agreed atKalmarinSwedenas designed by widowed QueenMargaretof Denmark. From 1397 to 1523,[1]it joined under a single monarch the three kingdoms ofDenmark,Sweden(then including much of present-dayFinland), andNorway,together withNorway's overseas colonies[b](then includingIceland,Greenland,[c]theFaroe Islands,and theNorthern IslesofOrkneyandShetland).

The union was not quite continuous; there were several short interruptions. Legally, the countries remained separatesovereign states.However, their domestic and foreign policies were directed by a common monarch.Gustav Vasa's election as King of Sweden on 6 June 1523, and his triumphantentry into Stockholmeleven days later, marked Sweden's final secession from the Kalmar Union.[2]Formally, the Danish king acknowledged Sweden's independence in 1524 at theTreaty of Malmö.

Inception

[edit]The union was the work of Scandinavian aristocracy who sought to counter the influence of theHanseatic League,a northern German trade league centered around the Baltic and North Seas. Denmark in particular was in apower struggle with the Leagueand recently suffered ahumiliating defeat in 1370that allowed the Hanseatic League to become even more powerful. More personally, it was achieved by QueenMargaret I of Denmark(1353–1412). She was a daughter of KingValdemar IVand had married KingHaakon VI of Norwayand Sweden, who was the son of KingMagnus IV of Sweden,Norway andScania.Margaret succeeded in having her and Haakon's sonOlafrecognized as heir to the throne of Denmark. In 1376 Olaf inherited the crown of Denmark from his maternal grandfather as King Olaf II, with his mother as guardian; when Haakon VI died in 1380, Olaf also inherited the crown of Norway.[3]

Margaret became regent of Denmark and Norway when Olaf died in 1387, leaving her without an heir.[4]She adopted her great-nephewEric of Pomeraniathe same year.[5]The following year, 1388, Swedish nobles called upon her help against KingAlbert.[6]After Margaret defeated Albert in 1389, her heir Eric was proclaimed King of Norway.[4]Eric was subsequently elected King of Denmark and Sweden in 1396 under the banner of theHouse of Griffin.[4]His coronation was held inKalmaron 17 June 1397.[7]

One main impetus for its formation was to block German expansion northward into theBaltic region.The main reason for its failure to survive was the perpetual struggle between the monarch, who wanted a strong unified state, and the Swedish and Danish nobility, which did not.[8]

The Union lost territory whenOrkneyandShetlandwerepledgedbyChristian I,in his capacity as King of Norway, as security against the payment of thedowryof his daughterMargaret,betrothed toJames III of Scotlandin 1468.[9]The money was never paid, so in 1472 the islands were annexed by theKingdom of Scotland.[10]

Internal conflict

[edit]Diverging interests (especially theSwedish nobility's dissatisfaction with the dominant role played by Denmark andHolstein) gave rise to a conflict that hampered the union in several intervals starting in the 1430s. TheEngelbrekt rebellion,which started in 1434, led to the overthrow of King Erik (in Denmark and Sweden in 1439, as well as Norway in 1442).[11]The aristocracy sided with the rebels.[11]

King Erik's foreign policy, in particular his conflict with the Hanseatic League, necessitated greater taxation and complicated exports of iron, which in turn may have precipitated the rebellion.[11]Discontent with the nature of King Erik's regime has also been cited as a motivating factor for the rebellion.[11]King Erik also lacked a standing army and had limited tax revenues.[11]

The death ofChristopher of Bavaria(who had no heirs) in 1448 ended a period in which the three Scandinavian kingdoms were uninterruptedly united for a lengthy period.[11]Karl Knutsson Bonderuled as king of Sweden (1448–1457, 1464–1465 and 1467–1470) and Norway (1449-1450).Christian of Oldenburgwas king of Denmark (1448–1481), Norway (1450–1481) and Sweden (1457–1464). Karl and Christian fought over control of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, leading Christian to seize Sweden from him from 1457 to 1464 before a rebellion led Karl to become king of Sweden again.[11]When Karl died in 1470, Christian tried to become king of Sweden again, but was defeated bySten Sture the Elderin the 1471battle of Brunkebergoutside Stockholm.[11]

After the death of Karl, Sweden was mostly ruled by a series of "protectors of the realm" (riksföreståndare), with the Danish kings attempting to assert control. First of these protectors was Sten Sture, who kept Sweden under his control until 1497 when the Swedish nobility deposed him. A peasant rebellion led Sture to become regent of Sweden again in 1501. After his death, Sweden was ruled bySvante Nilsson(1504–1512) and then Svante's sonSten Sture the Younger(1512–1520).[11]Sten Sture the Younger was killed in the 1520 Battle of Bogesund when the Danish kingChristian IIinvaded Sweden with a large army.[11]Subsequently, Christian II was crowned King of Sweden, and supporters of Sten Sture were executed en masse in theStockholm Bloodbath.[11]

Swedish War of Liberation

[edit]After the Stockholm Bloodbath,Gustav Vasa(whose father,Erik Johansson,was executed) travelled toDalarna,where he organized arebellionagainst Christian II.[11]Vasa made an alliance with Lübeck and successfully conquered most of Sweden.[11]He was elected King of Sweden in 1523, effectively ending the Kalmar Union.[11]After theNorthern Seven Years' War,theTreaty of Stettin (1570)sawFrederick IIrenounce all claims to Sweden.[12]

End and aftermath

[edit]One of the last structures of the Union remained until 1536/1537 when theDanish Privy Council,in the aftermath of theCount's Feud,unilaterally declared Norway to be aDanish province.This did not happen. Instead, Norway became a hereditary kingdom in areal unionwith Denmark.[13][14]Norway continued to remain a part of the realm ofDenmark–Norwayunder theOldenburg dynastyfor nearly three centuries, until it wastransferred to Swedenin 1814. The ensuingunion between Sweden and Norwaylasted until 1905, when princeCarl of Denmark,a grandson of both theincumbent king of Denmarkand thelate king of Sweden,was elected king of Norway.[15]

According to historian Sverre Bagge, the Kalmar Union was unstable for several reasons:[9]

- The power of national aristocracies.

- The varied effects of the Kalmar Union's foreign policy on the three kingdoms. For example, attempted expansions into Northern Germany may have served Danish interests, but was costly to Swedes who had to pay higher taxes and were unable to export iron to the Hanseatic League.

- Geography complicated control of the union in the event of rebellion.

- The large territorial size of the union complicated control.

- Denmark was not strong enough to force Norway and Sweden to stay within the union.

Gallery

[edit]The Kalmar Union monarchs were:

-

Queen Margaret

-

King Eric

-

King Christopher

-

King Christian I

-

King John ( "Hans" )

-

King Christian II

See also

[edit]- List of Kalmar Union monarchs

- Scandinavian royal lineage chart for the time around the founding of the Kalmar Union

Notes

[edit]- ^Danish,Norwegian,andSwedish:Kalmarunionen;Finnish:Kalmarin unioni;Icelandic:Kalmarsambandið;Latin:Unio Calmariensis

- ^Norway retained none of its prior possessions, however. Christian I pledged theNorthern IslestoScotlandas insurance for his daughter's dowery in 1468; the dowery was not paid, and the islands transferred to perpetual Scottish sovereignty in 1470. After the Union's dissolution, all remaining overseas possessions brought into the Union by Norway became property of the Danish monarch, who retained ownership following the transfer of the Kingdom of Norway from the Danish crown to Swedish crown (discussed in further detail below) after theNapoleonic Wars.

- ^Nominal possession: Norway claimed suzerainty over the island prior to the Union's formation, but it had long since ceased exercising any administrative control over the European settlements there. No direct contact took place between Greenland and the Kalmar Union during the latter's existence.

References

[edit]- ^Gustafsson, Harald (September 2006)."A STATE THAT FAILED?: On the Union of Kalmar, Especially its Dissolution".Scandinavian Journal of History.31(3–4): 205–220.doi:10.1080/03468750600930720.ISSN0346-8755.

- ^Sampson, Anastacia."Swedish Monarchy – Gustav Vasa".sweden.org.za o. Archived fromthe originalon 14 August 2018.Retrieved1 August2018.

- ^Karlsson, Gunnar (2000).The History of Iceland.p. 102.

- ^abc"Margaret I | queen of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved5 June2017.

- ^"Erik VII | king of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved5 June2017.

- ^"Sweden – Code of law | history – geography".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved5 June2017.

- ^"Kalmar Union | Scandinavian history".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved5 June2017.

- ^For a somewhat different view see"The Union Of Calmar —Nordic Great Power Or Northern German Outpost?".Politics and reformations: communities, polities, nations, and empires essays in honor of Thomas A. Brady, Jr.Studies in Medieval and Reformation traditions. Leiden: Brill. 2007. pp. 471–472.ISBN978-90-04-16173-3.

- ^abBagge, Sverre (2014).Cross and Scepter: The Rise of the Scandinavian Kingdoms from the Vikings to the Reformation.Princeton University Press. pp. 260–268.ISBN978-1-4008-5010-5.

- ^Nicolson (1972) p. 45

- ^abcdefghijklmnBagge, Sverre (2014).Cross and Scepter: The Rise of the Scandinavian Kingdoms from the Vikings to the Reformation.Princeton University Press. pp. 251–259.ISBN978-1-4008-5010-5.

- ^Bain, Robert Nisbet(1905).Scandinavia: A Political History of Denmark, Norway and Sweden from 1513 to 1960.Adegi Graphics LLC. p. 83.ISBN978-0-543-93900-5.

- ^Moseng, Ole Georg (2003).Norges historie 1537–1814.Universietsforlaget AS. p. 27.ISBN978-82-15-00102-9.

- ^Nordstrom, Byron (2000).Scandinavia since 1500.University of MinnesotaPress. p.147.ISBN0-8166-2098-9.

- ^"Jubilee".Time.8 December 1930. p. 1. Archived fromthe originalon 13 August 2009.Retrieved17 December2008.

Further reading

[edit]- Albrectsen, Esben, ed. (1997).Danmark-Norge. 1: Fællesskabet bliver til / af Esben Albrectsen.Oslo: Univ.Forl.ISBN978-87-500-3496-4.

- Carlsson, Gottfrid (1945).Medeltidens nordiska unionstanke(in Swedish). Geber.

- Christensen, Aksel Erhardt (1980).Kalmarunionen og nordisk politik 1319-1439.København: Gyldendal.ISBN978-87-00-51833-9.

- Enemark, Poul (1979).Fra Kalmarbrev til Stockholms blodbad: den nordiske trestatsunions epoke 1397-1521.Temahæfter i Nordens historie. København: Nordisk ministerråd: Gyldendal.ISBN978-87-01-80611-4.

- Gustafsson, Harald (20 October 2017). "The Forgotten Union: Scandinavian dynastic and territorial politics in the 14th century and the Norwegian-Swedish connection".Scandinavian Journal of History.42(5): 560–582.doi:10.1080/03468755.2017.1374028.ISSN0346-8755.

- Harrison, Dick(2020).Kalmarunionen: en nordisk stormakt föds.Lund: Historiska media.ISBN978-91-7789-167-3.

- Helle, Knut; Kouri, E. I.; Olesen, Jens E., eds. (2003).The Cambridge history of Scandinavia.Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-47299-9.OCLC53893623.

- Politics and reformations: communities, polities, nations, and empires essays in honor of Thomas A. Brady, Jr.Studies in Medieval and Reformation traditions. Leiden: Brill. 2007.ISBN978-90-04-16173-3.

- Kirby, David (2014).Northern Europe in the Early Modern Period: The Baltic World 1492-1772.Routledge.ISBN978-1-317-90214-0.

- Larsson, Lars-Olof (2003).Kalmarunionens tid: från drottning Margareta till Kristian II(2. uppl ed.). Stockholm: Prisma.ISBN978-91-518-4217-2.

- Roberts, Michael (1986).The early Vasas: a history of Sweden, 1523-1611.Cambridge: Univ. Press.ISBN978-0-521-31182-3.

External links

[edit] Media related toKalmar Unionat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toKalmar Unionat Wikimedia Commons- The Kalmar Union– Maps of the Kalmar Union

- Kalmar Union

- 1397 establishments in Europe

- 14th century in Denmark

- 14th century in Finland

- 14th century in Norway

- 14th century in Sweden

- 14th-century establishments in Denmark

- 14th-century establishments in Norway

- 14th-century establishments in Sweden

- 1520s disestablishments in Sweden

- 15th century in Denmark

- 15th century in Finland

- 15th century in Norway

- 15th century in Sweden

- 16th century in Denmark

- 16th century in Finland

- 16th century in Norway

- 16th century in Sweden

- 16th-century disestablishments in Denmark

- 16th-century disestablishments in Norway

- Monarchy of Denmark

- Kalmar

- Monarchy of Norway

- Personal unions

- History of Scandinavia

- States and territories established in 1397

- Monarchy of Sweden

- Margaret I of Denmark

- Former monarchies

- Former state unions

- Former monarchies of Europe