Hoi Tong Monastery

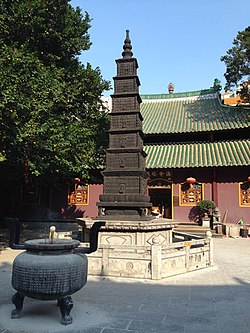

The iron Thousand Buddha Tower in the monastery's courtyard | |

| Site | |

|---|---|

| Location | Guangzhou,China |

| Coordinates | 23°6′28″N113°15′13″E/ 23.10778°N 113.25361°E |

| |

| Hoi Tong Monastery | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The temple's main gate | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | HảiTràngChùa | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Sea-Banner Temple | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Qianqiu Temple | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | NgànThuChùa | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Thousand-Autumn Temple | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Hai giường Park | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | HảiTràngCông viên | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | HảiTràngCông viên | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Sea Banner Public Park | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Henan Park | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Hà NamCông viên | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Hà NamCông viên | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | South of the RiverPublic Park | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Part ofa serieson |

| Chinese Buddhism |

|---|

|

TheHoi Tong Monastery,[1]also known bymany other names,is aBuddhisttempleandmonasteryonHenan IslandinGuangzhou,China. It shares its grounds with the city'sHai giường Park.

Names

[edit]The official English form of the name is "Hoi Tong Monastery",[1]a transcription of theCantonesepronunciation of theChinesetranslation of the IndianBuddhist monkSāgaradhvaja[2][3][4](Sanskrit:सागरध्वज,lit"Ocean[5]Banner "[6]or "Flagpole" ),[7]who appears in theFlower Garland Sutraas a devout student of theHeart Sutra.[1]Variants includeHoi Tong Temple;[8]the translationsOcean Banner Temple[9]orMonastery,[10][11]Sea Banner Temple,[12]andSea Screen[13][14]orSea-screen Temple;theMandarinHae Chwang,[15]Hai giường,[16]andHai- giường Temple;[9]and the misreadings "Hoy Hong Temple"[17]and "Haizhuang Temple".[18]

From its location, it has also been known as theTemple of Honan[19]orHonam.[13][14]

History

[edit]

The monastery was first established as theQianqiu Templeunder theSouthern Han,[1]a 10th-centuryTangsuccessor state whose capital was at Xingwang (nowGuangzhou). The walled city lay north of thePearl River,while Henan Island and the monastery lay to its south. By the end of theMing,the temple operated within the private garden of Guo Longyue (QuáchLongNhạc).[10]He was responsible for renaming it after theBuddhist monkSāgaradhvaja.[1]

The monastery, surrounded by majesticbanyan trees,[19]flourished under the earlyQing.Jin Bao (KimBảo), a formerministerof theYongli Emperor,retired here. During the reign of theKangxi Emperor,it was expanded continuously by the monks Azi (ATự), Chee Yut,[10]and others,[1]sometimes prompting English sources to place its establishment in 1662.[10]Around a hundred monks lived at the monastery; the treatment of the wealthy and poor members was very unequal.[20]It was the principal temple for Henan (then known as "Ho-nan" )[21]and sometimes even acclaimed the most famous of southern China's Buddhist temples.[19][22]

The temple complex was particularly important to foreign visitors as it was one of the few locations inGuangzhou( "Canton" ) open to them before theFirst Opium War.Themain hall's large buddhas were removed to other temples[23][20]so thatLord Amherstand his retinue could rest there for three weeks 1–20 January 1817[24]before returning home viaMacaofollowing their failed embassy to Beijing ( "Pekin" ). TheFrenchartistAuguste Borgetvisited the temple repeatedly during his world tour, stating "The noise outside the temple was so great and the silence inside the temple was so solemn, that I believed myself transported to another world".[25]The temple faced the row offactorieson Guangzhou's waterfront. Regulations issued in 1831 restricted foreign access to its grounds to the 8th, 18th, and 28th days of thelunar months.[9]Prior to the advent ofphotography,paintings of the grounds at Hoi Tong made up one of the fifteen classes of Qing export paintings.[26][n 1]

At the time, the river entrance was the most used, leading to a courtyard guarded by a pair of wooden statues. Beyond, there were flagged walks amid banyan trees, leading to colonnades filled with numerous idols "of every sect and profession". At the far end were three halls, the center of which held three 11-foot (3.4 m) idols of the Buddhas past, present, and yet-to-come— "Kwo-keu-fuh","Heen-tsa-fuh",and"We-lae-fuh"—in a seated position. On each side were 18 earlydisciples of the Buddha,considered at the time to have been the precursors to theQingemperors.[27]Illustrations were made of the trial and punishment of sinners in the afterlife, but none of the Buddhist paradises.[22]The side walls were covered with silk embroidered in gold and silver thread with passages of scripture, and the whole lit with several hundred lanterns suspended from the roof's crossbeams.[20]The garden includedrare plantsandpenjing,miniature trees grown into the shape of boats and birdcages.[13]On the grounds, pigs and other animals[28]were kept as an "illustration of the Buddhist tenet not to destroy but to care for animal life".[29]The pigs became famous, some being so enormously fat that they were nearly unable to walk.[29]Some of thestieswere located with the temples and, upon their deaths, they were accordedfunereal ritesand laid within a special mausoleum on the grounds.[20]Its library was well stocked. The monastery ran its own printing press,[13][14]as well as a crematorium and mausoleum for the monks.[29][28]Thisdagobawas considered "magnificent", if not on the level ofBeijing'sBaita.[30]The abbot's cell included a separate reception room and a small chapel with a shrine to Buddha.[13][14]The entire grounds spread over about 7 acres (2.8 ha).[15]

The monastery was also a site for instruction inkung fu.[31]The master Liang Kun (Leung Kwan) died while training in the 36-Point Copper Ring Pole technique under the monk Yuanguang in 1887.[32]In the 1920s, it housed Guangzhou'sChin Woo Athletic Association.[33]

The great trees of the monastery were ruined during theTaiping Rebellion.[29]The monastery faded from importance in foreign guidebooks after theOpium Warsopened Guangzhou proper to visitors,[34]although the principal factories were removed to Henan during the years 1856–1859 after a devastating fire along the north bank and the number of monks grew as high as 175.[15]During the reign of theEmpress Dowager Cixi,the area around the monastery became more residential and it began to fade.[1]As part of the educational reforms surrounding the end of theimperial examinationsystem, the monastery was obliged to make room for the Nanwu Public School (Nam võCông học).[35]It was severely damaged during the early years of theRepublic,[1]although it was protected for a time by local elites.[36]The entire compound aside from two halls was demolished and in 1928 its land was confiscated and opened asHenan Park.[1]Its scriptures were removed to a public library.[37]An official embassy of the city's Buddhists to the capital atNanjingthe next year was a failure, but the park was permitted to keep some of its idols as statues "for public appreciation". Praying and burningincensein the park were outlawed, but locals continued to tie paper offerings to the Buddhas and several women came at night to pray. Their murmuring was sometimes mistaken by other visitors as the sounds of ghosts haunting the grounds.[38]In September 1933, the area was renamed "Hai giường Park". The surviving buildings of the complex were severely damaged again during theCultural Revolutionof the late 1960s and early '70s.[1]

Following China'sopening up,the Guangzhou Municipal People's Government permitted the monastery to resume official operation in 1993, identifying it as a heritage conservation unit. The grounds of the monastery were repaired and renovated but continue to only occupy the western half of the former site, the rest making up Guangzhou's Hai giường Park. This was restored to the temple by the Haizhu District People's Government on 1 July 2006[1]but remains open to the public.

Abbots

[edit]The presentabbotis Master Xincheng (TânThành).[18]

Gallery

[edit]-

The "Sea-screen Temple at Honam" in 1838, byAuguste Borget,including some of the temple's sacred pigs.[25]

-

The landing place and river entrance to the "Temple of Honan" in the 1840s.[19]

-

The "Great Templeat Honan "in the 1840s.[22]

-

The entrance to the inner courtyards of "Honam Temple" in 1874[13]

-

The land entrance to the "Chinese monastery at Ho Nam" in 1903.[39]

-

Monks at the monastery in 1903.[39]

See also

[edit]- Chinese Buddhism

- List of Buddhist temples

- Guangxiao Temple (Guangzhou)

- Hualin Temple (Guangzhou)

- Temple of the Six Banyan Trees

Notes

[edit]- ^The other fourteen were thecityandportof Guangzhou, its markets and street vendors, its government offices and paraphrenalia, itsriverine and maritime traffic,Chinese clothing,the workshops ofFoshan,Chinese punishments,Chinese gardensandmansions,itsreligious architectureandrituals,opium addicts,Chinese interior decorating including its plants and birds,Chinese opera,Beijing life and customs, and its shop signs.[26]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abcdefghijkOfficial site (2016).

- ^Ding Fubao [ đinh phúc bảo ] (1922),Phật học đại từ điển,53 trí thức.(in Chinese)

- ^Osto, Douglas (2008),Power, Wealth, and Women in Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Gaṇḍavyūha-sūtra,Abingdon: Routledge, p.136.

- ^"Sanskrit Personal Names Index",Digital Dictionary of Buddhism,2015.

- ^"sāgara सागर",Sanskrit Dictionary.

- ^"dhvaja ध्वज",Sanskrit Dictionary.

- ^"dhvaja ध्वज",Sanskrit Dictionary.

- ^The China Journal,vol. 30, 1939, p. 141.

- ^abcGarrett (2002),p. 113.

- ^abcdGray (1875),p.34.

- ^Garrett (2002),p. 114.

- ^Neumann, Karl Friedrich (1831),"The Laws of the Shamans",The Catechism of the Shamans; or, the Laws and Regulations of the Priesthood of Buddha in China,London: Oriental Translation Fund, p.37.

- ^abcdefThomson (1874),"Honam Temple, Canton".

- ^abcdHunter (1885),p.176.

- ^abcThe People's Cyclopedia of Universal Knowledge,vol. I, Phillips & Hunt, 1883, "Canton", p. 364.

- ^Tarocco, Francesca (2007),The Cultural Practices of Modern Chinese Buddhism: Attuning the Dharma,London: Routledge, p.48,ISBN9781136754395.

- ^"Birth Place",Fu-Jow Pai Federation,2011.

- ^abJiang Wu (7 August 2015),"Haizhuang Temple in Guangzhou",Leaving for the Rising Sun.

- ^abcdWright (1843),p.10.

- ^abcdWright (1843),p.11.

- ^Ellis (1817),pp.407.

- ^abcWright (1843),p.66.

- ^Ellis (1817),pp.420.

- ^Ellis (1817),pp.407–21.

- ^ab"The Sea-screen Temple at Honam, Canton",Hong Kong Museum of Art,Google Arts & Culture.

- ^abKit, Eva Wah Man (17 August 2015), "Influence of Global Aesthetics on Chinese Aesthetics: The Adaption ofMoxieand the Case of Dafen Cun ",Issues of Contemporary Art and Aesthetics in Chinese Context,Chinese Contemporary Art Series, Heidelberg: Springer, pp.97–8,ISBN978-3-662-46509-7.

- ^Wright (1843),p.10–11.

- ^abSeward (1873),p.240–1.

- ^abcdHunter (1885),p.177.

- ^Gray, John Henry (1878),China: A History of the Laws, Manners, and Customs of the People,vol. I, London: Macmillan & Co., p.123,ISBN9780486160733.

- ^Lam Sai Wing (2002),Iron Thread,Southern Shaolin Hung Gar Kung Fu, Lulu Press, p.30,ISBN9781847991928.

- ^"The Famous Masters of Hung Gar",European Hung Gar Association,2001, archived from the original on 2006-05-07,retrieved2017-08-29

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - ^Kennedy, Brian; et al. (15 June 2010),Jingwu: The School that Transformed Kung Fu,Berkeley: Blue Snake Books, p.140,ISBN978-1-58394-242-0.

- ^Garrett (2002),p. 123.

- ^Poon (2011),p.25.

- ^Poon (2011),p.55.

- ^Poon (2011),p.127.

- ^Poon (2011),p.75.

- ^abWood, Dick (23 December 1903),"Come with Me to China",The Tacoma Times,p. 2.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Brief Introduction of Hoi Tong Monastery",Official website,Guangzhou: Hoi Tong Monastery, 2016.(in Chinese)&(in English)

- Ellis, Henry (1817),Journal of the Proceedings of the Late Embassy to China, Comprising a Correct Narrative of the Public Transactions of the Embassy, of the Voyage to and from China, and of the Journey from the Mouth of the Pei-Ho to the Return to Canton, Interspersed with Observations upon the Face of the Country, the Polity, Moral Character, and Manners of the Chinese Nation,London: John Murray.

- Garrett, Valery M. (2002),Heaven is High, the Emperor Far Away: Merchants and Mandarins in Old Canton,Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gray, John Henry (1875),Walksin the City of Canton,Hong Kong: De Souza & Co..

- Hunter, William (1885),Bits of Old China,London: Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co..

- Poon Shuk-wah (2011),Negotiating Religion in Modern China: State and Common People in Guangzhou, 1900–1937,Hong Kong: Chinese University Press,ISBN978-962-996-421-4.

- William H. Seward's Travels around the World,New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1873.

- Thomson, John(1874),Illustrations of China and Its People: A Series of Two Hundred Photographs with Letterpress Descriptive of the Places and People Represented,vol. I, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, & Searle.

- Wright, G.N. (1843),China, in a Series of Views, Displaying the Scenery, Architecture, and Social Habits, of that Ancient Empire,vol. III, London: illustrated byThomas Allomfor Fisher, Son, & Co.

External links

[edit]- "Quảng Châu hải tràng chùa"atBaike(in Chinese)

![The "Sea-screen Temple at Honam" in 1838, by Auguste Borget, including some of the temple's sacred pigs.[25]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/The_Sea-screen_Temple_at_Honam_Canton.png/120px-The_Sea-screen_Temple_at_Honam_Canton.png)

![The landing place and river entrance to the "Temple of Honan" in the 1840s.[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3d/Landing_Place_and_Entrance_to_the_Temple_of_Honan_Canton.png/120px-Landing_Place_and_Entrance_to_the_Temple_of_Honan_Canton.png)

![The "Great Temple at Honan" in the 1840s.[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Great_Temple_at_Honan%2C_Canton.png/120px-Great_Temple_at_Honan%2C_Canton.png)

![The entrance to the inner courtyards of "Honam Temple" in 1874[13]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/HONAM_TEMPLE%2C_CANTON.jpg/96px-HONAM_TEMPLE%2C_CANTON.jpg)

![The land entrance to the "Chinese monastery at Ho Nam" in 1903.[39]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Entrance_to_Hoi_Tong_Monastery%2C_1903.JPG/120px-Entrance_to_Hoi_Tong_Monastery%2C_1903.JPG)

![Monks at the monastery in 1903.[39]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Monks_at_Hoi_Tong_monastery%2C_Ho_Nam%2C_China_%281903%29.jpg/120px-Monks_at_Hoi_Tong_monastery%2C_Ho_Nam%2C_China_%281903%29.jpg)