Equisetum

| Equisetum Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| "Candocks" ofEquisetum telmateiasubsp.telmateia(great horsetail), showing whorls of branches and the tiny dark-tipped leaves | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Polypodiophyta |

| Class: | Polypodiopsida |

| Subclass: | Equisetidae |

| Order: | Equisetales |

| Family: | Equisetaceae |

| Genus: | Equisetum L. |

| Type species | |

| Equisetum arvense | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Equisetum(/ˌɛkwɪˈsiːtəm/;horsetail,marestail,snake grass,puzzlegrass) is the only livinggenusinEquisetaceae,afamilyofvascular plantsthat reproduce bysporesrather than seeds.[2]

Equisetumis a "living fossil",the only living genus of the entiresubclassEquisetidae,which for over 100 million years was much more diverse and dominated theunderstoreyof latePaleozoicforests. Some equisetids were largetreesreaching to 30 m (98 ft) tall.[3]The genusCalamitesof the familyCalamitaceae,for example, is abundant incoaldeposits from theCarboniferousperiod. The pattern of spacing of nodes in horsetails, wherein those toward the apex of the shoot are increasingly close together, is said to have inspiredJohn Napierto inventlogarithms.[4]Modern horsetails first appeared during theJurassicperiod.

A superficially similar but entirely unrelatedflowering plantgenus, mare's tail (Hippuris), is occasionally referred to as "horsetail", and adding to confusion, the name "mare's tail" is sometimes applied toEquisetum.[5]

Etymology[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(August 2018) |

The name "horsetail", often used for the entire group, arose because the branched species somewhat resemble ahorse's tail. Similarly, thescientific nameEquisetumis derived from theLatinequus('horse') +seta('bristle').[6]

Other names includecandockfor branching species, andsnake grassorscouring-rushfor unbranched or sparsely branched species. The latter name refers to therush-like appearance of the plants and to the fact that the stems are coated with abrasivesilicates,making them useful for scouring (cleaning) metal items such as cooking pots or drinking mugs, particularly those made oftin.Equisetum hyemale,rough horsetail, is still boiled and then dried inJapanto be used for the final polishing process onwoodcraftto produce a smooth finish.[7]InGerman,the corresponding name isZinnkraut('tin-herb'). InSpanish-speaking countries, these plants are known ascola de caballo('horsetail').

Description[edit]

Equisetumleavesare greatly reduced and usually non-photosynthetic.They contain a single, non-branchingvascular trace,which is the defining feature ofmicrophylls.However, it has recently been recognised that horsetail microphylls are probably not ancestral as inlycophytes(clubmosses and relatives), but rather derivedadaptations,evolved by reduction ofmegaphylls.[8]

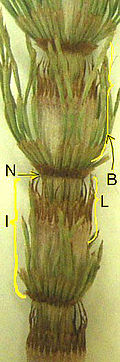

The leaves of horsetails are arranged inwhorlsfused intonodalsheaths. The stems are usually green and photosynthetic, and are distinctive in being hollow, jointed and ridged (with sometimes 3 but usually 6–40 ridges). There may or may not be whorls of branches at the nodes.[citation needed]Unusually, the branches often emerge below the leaves in an internode, and grow from buds between their bases.

B = branch in whorl

I = internode

L = leaves

N = node

The small white protuberances are accumulatedsilicatesoncells.

Spores[edit]

Thesporesare borne undersporangiophoresinstrobili,cone-like structures at the tips of some of the stems. In many species the cone-bearing shoots are unbranched, and in some (e.g.E. arvense,field horsetail) they are non-photosynthetic, produced early in spring. In some other species (e.g.E. palustre,marsh horsetail) they are very similar to sterile shoots, photosynthetic and with whorls of branches.[9]: 12–15

Horsetails are mostlyhomosporous,though in the field horsetail, smaller spores give rise to maleprothalli.The spores have fourelatersthat act as moisture-sensitive springs, assisting spore dispersal through crawling and hopping motions after thesporangiahave split open longitudinally.[10]They are photosynthetic and have a lifespan that is usually two weeks at most, but will germinate immediately under humid conditions and develop into agametophyte.[11]

Cell walls[edit]

The crude cell extracts of allEquisetumspecies tested containmixed-linkage glucan: xyloglucan endotransglucosylase(MXE) activity.[12]This is a novel enzyme and is not known to occur in any other plants. In addition, the cell walls of allEquisetumspecies tested containmixed-linkage glucan(MLG), apolysaccharidewhich, until recently, was thought to be confined to thePoales.[13][14]The evolutionary distance betweenEquisetumand the Poales suggests that each evolved MLG independently. The presence of MXE activity inEquisetumsuggests that they have evolved MLG along with some mechanism of cell wall modification. Non-Equisetumland plants tested lack detectable MXE activity. An observed negative correlation betweenXETactivity and cell age led to the suggestion that XET is catalysing endotransglycosylation in controlled wall-loosening during cell expansion.[15]The lack of MXE in the Poales suggests that there it must play some other, currently unknown, role. Due to the correlation between MXE activity and cell age, MXE has been proposed to promote the cessation of cell expansion.[citation needed]

Taxonomy[edit]

Species[edit]

The living members of the genusEquisetumare divided into three distinct lineages, which are usually treated assubgenera.The name of the type subgenus,Equisetum,means "horse hair" inLatin,while the name of the other large subgenus,Hippochaete,means "horse hair" inGreek.Hybridsare common, but hybridization has only been recorded between members of the same subgenus.[16]While plants of subgenusEquisetumare usually referred to as horsetails, those of subgenusHippochaeteare often called scouring rushes, especially when unbranched.[citation needed]

TwoEquisetumplants are sold commercially under the namesEquisetum japonicum(barred horsetail) andEquisetum camtschatcense(Kamchatka horsetail). These are both types ofE. hyemalevar.hyemale,although they may also be listed as separate varieties ofE. hyemale.[17][citation needed]

Evolutionary history[edit]

The oldest remains of modern horsetails of the genusEquisetumfirst appear in the Early Jurassic, represented byEquisetum dimorphumfrom the Early Jurassic of Patagonia[18]andEquisetum lateralefrom the Early-Middle Jurassic of Australia.[19][20]Silicifiedremains ofEquisetum thermalefrom the Late Jurassic of Argentina exhibit all the morphological characters of modern members of the genus.[21]The estimated split betweenEquisetum bogotenseand all other livingEquisetumis estimated to have occurred no later than the Early Jurassic.[20]

SubgenusParamochaete[edit]

- Equisetum bogotenseKunth– Andean horsetail; uplandSouth Americaup toCosta Rica;includesE. rinihuense,sometimes treated as a separate species. Previously included in subg.Equisetum,but Christenhuszet al.(2019)[22]transfer this here, asE. bogotenseappears to be sister to the remaining species in the genus.

SubgenusEquisetum[edit]

- Equisetum arvenseL.– field horsetail, common horsetail or mare's tail; circumboreal down through temperate zones

- Equisetum diffusumD.Don– Himalayan horsetail; Himalayan India and China and adjacent nations above about 1500 feet (450 m)

- Equisetum fluviatileL.– water horsetail; circumboreal down through temperate zones

- Equisetum palustreL.– marsh horsetail; circumboreal down through temperate zones

- Equisetum pratenseEhrh.– meadow horsetail, shade horsetail, shady horsetail; circumboreal except for tundra down through cool temperate zones

- Equisetum sylvaticumL.– wood horsetail; circumboreal down through cool temperate zones, more restricted in east Asia

- Equisetum telmateiaEhrh.– great horsetail, northern giant horsetail; Europe to Asia Minor and north Africa, also west coast of North America. The North American subspeciesEquisetum telmateia braunii(Milde) Hauke.may be treated as a separate speciesEquisetum brauniiMilde[22]

SubgenusHippochaete[edit]

- Equisetum calderi– Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut and possibly North Slope of Alaska.

- Equisetum giganteumL.– southern giant horsetail or giant horsetail; temperate to tropical South America and Central America north to southern Mexico

- Equisetum hyemaleL.– rough horsetail, rough scouring rush; most of non-tropical northern hemisphere. The North American subspeciesEquisetum hyemale affine(Engelm.) A.A.Eat.may be treated as a separate speciesEquisetum prealtumRaf.[22]

- Equisetum laevigatumA.Braun– smooth horsetail, smooth scouring rush; western 3/4 of North America down into northwestern Mexico; also sometimes known asEquisetum kansanum

- Equisetum myriochaetumSchltdl.&Cham.– Mexican giant horsetail; from central Mexico south to Peru

- Equisetum ramosissimumDesf.(includingE. debile) – branched horsetail; Asia, Europe, Africa, southwest Pacific islands

- Equisetum scirpoidesMichx.– dwarf horsetail, dwarf scouring rush; northern (cool temperate) zones worldwide

- Equisetum variegatumSchleich.exWeber&Mohr– variegated horsetail, variegated scouring rush; northern (cool temperate) zones worldwide, except for northeasternmost Asia

Unplaced to subgenus[edit]

- †Equisetum dimorphum–Early Jurassic,Argentina

- †Equisetum laterale–Early toMiddle Jurassic,Australia

- †Equisetum thermale– Middle toLate Jurassic,Argentina

- †Equisetum similkamense–Ypresian,British Columbia

Named hybrids[edit]

Hybrids between species in subgenusEquisetum[edit]

- Equisetum×bowmaniiC.N.Page(Equisetum sylvaticum×Equisetum telmateia)

- Equisetum×dyceiC.N.Page(Equisetum fluviatile×Equisetum palustre)

- Equisetum×font-queriRothm.(Equisetum palustre×Equisetum telmateia)

- Equisetum×litoraleKühlew exRupr.(Equisetum arvense×Equisetum fluviatile)

- Equisetum×mchaffieaeC.N.Page(Equisetum fluviatile×Equisetum pratense)

- Equisetum×mildeanumRothm.(Equisetum pratense×Equisetum sylvaticum)

- Equisetum×robertsiiDines(Equisetum arvense×Equisetum telmateia)

- Equisetum×rothmaleriC.N.Page(Equisetum arvense×Equisetum palustre)

- Equisetum×willmotiiC.N.Page(Equisetum fluviatile×Equisetum telmateia)

Hybrids between species in subgenusHippochaete[edit]

- Equisetum×ferrissiiClute(Equisetum hyemale×Equisetum laevigatum)

- Equisetum×mooreiNewman(Equisetum hyemale×Equisetum ramosissimum)

- Equisetum×nelsonii(A.A.Eaton) Schaffn.(Equisetum laevigatum×Equisetum variegatum)

- Equisetum×schaffneriMilde(Equisetum giganteum×Equisetum myriochaetum)

- Equisetum×trachyodon(A.Braun) W.D.J.Koch(Equisetum hyemale×Equisetum variegatum)

Phylogeny[edit]

| Christenhuszet al.2019[22] | Nitta et al. 2022[23]and Fern Tree of life[24] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Distribution and ecology[edit]

The genusEquisetumas a whole, while concentrated in the non-tropical northern hemisphere, is near-cosmopolitan,being absent only fromAntarctica,though they are not known to be native to Australia, New Zealand nor the islands of the Pacific. They are most common in northern North America (Canada and the northernmost United States), where the genus is represented by nine species (E. arvense,E. fluviatile,E. hyemale,E. laevigatum,E. palustre,E. pratense,E. scirpoides,E. sylvaticum',andE. variegatum). Only four (E. bogotense,E. giganteum,E. myriochaetum,andE. ramosissimum) of the fifteen species are known to be native south of the Equator. They areperennial plants,herbaceousand dying back in winter as most temperate species, orevergreenas most tropical species and the temperate speciesE. hyemale(rough horsetail),E. ramosissimum(branched horsetail),E. scirpoides(dwarf horsetail) andE. variegatum(variegated horsetail). They typically grow 20 cm–1.5 m (8 in–5 ft) tall, though the "giant horsetails" are recorded to grow as high as 2.5 m (8 ft) (E. telmateia,northern giant horsetail), 5 m (16 ft) (E. giganteum,southern giant horsetail) or 8 m (26 ft) (E. myriochaetum,Mexican giant horsetail), and allegedly even more.[25]

One species,Equisetum fluviatile,is an emergentaquatic,rooted in water with shoots growing into the air. The stalks arise fromrhizomesthat are deep underground and difficult to dig out. Field horsetail (E. arvense) can be a nuisanceweed,readily regrowing from the rhizome after being pulled out. It is unaffected by manyherbicidesdesigned to killseed plants.[26][citation needed]Since the stems have a waxy coat, the plant is resistant to contact weedkillers like glyphosate.[27]However, asE. arvenseprefers an acid soil,limemay be used to assist in eradication efforts to bring thesoil pHto 7 or 8.[28]Members of the genus have been declared noxious weeds inAustraliaand in the US state ofOregon.[29][30]

All theEquisetumare classed as "unwanted organisms" inNew Zealandand are listed on theNational Pest Plant Accord.[31]

Consumption[edit]

People have regularly consumed horsetails. For example, the fertile stems bearing strobili of some species are cooked and eaten like asparagus[32](a dish calledtsukushi(Thổ bút)inJapan[33][failed verification]). Indigenous nations acrossCascadiaconsume and use horsetails in a variety of ways, with theSquamishcalling themsx̱ém'x̱emand theLushootseedusinggʷəɫik,or horsetail roots, for cedar root baskets.[34][35][36]The young plants are eaten cooked or raw, but considerable care must be taken.[37]

If eaten over a long enough period of time, some species of horsetail can bepoisonousto grazing animals, includinghorses.[38]The toxicity appears to be due tothiaminase,which can cause thiamin (vitamin B1) deficiency.[37][39][40][41]

Equisetumspecies may have been a common food for herbivorous dinosaurs. With studies showing that horsetails are nutritionally of high quality, it is assumed that horsetails were an important component of herbivorous dinosaur diets.[42]Analysis of the scratch marks on hadrosaur teeth is consistent with grazing on hard plants like horsetails.[43]

Folk medicine and safety concerns[edit]

Extracts and other preparations ofE. arvensehave served asherbal remedies,with records dating over centuries.[37][39][44]In 2009, theEuropean Food Safety Authorityconcluded there was no evidence for the supposedhealth effectsofE. arvense,such as for invigoration, weight control, skincare, hair health or bone health.[45]As of 2018[update],there is insufficient scientific evidence for its effectiveness as a medicine to treat any human condition.[37][44][45]

E. arvensecontainsthiaminase,which metabolizes theB vitamin,thiamine,potentially causingthiamine deficiencyand associatedliver damage,if taken chronically.[37][39]Horsetail might produce adiuretic effect.[37][39]Further, its safety for oral consumption has not been sufficiently evaluated and it may betoxic,especially to children and pregnant women.[37]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"EquisetumL. "Plants of the World Online.Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017.Retrieved23 August2020.

- ^Dunmire, John R.; Williamson, Joseph F. (1995). "EQUISETUM hyemale". In Brenzel, Kathleen N. (ed.).Western Garden Book.Menlo Park, CA: Sunset. pp. 274, 606.ISBN0376038500.

- ^"An Introduction to the GenusEquisetumand the Class Sphenopsida as a whole ".Florida International University.Archived fromthe originalon 2009-07-14.Retrieved2009-07-22.

- ^Sacks, Oliver (25 July 2011)."Hunting Horsetails".The Talk of the Town: Field Trip.The New Yorker.No. 11 August 2011.

- ^"Equisetum".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^Daniel F. Austin (2004).Florida Ethnobotany(illustrated ed.). CRC Press. p. 283.ISBN9780203491881.

- ^Husby, C (2013). "Biology and functional ecology ofEquisetumwith emphasis on the giant horsetails ".Botanical Review.79(2): 147–177.Bibcode:2013BotRv..79..147H.doi:10.1007/s12229-012-9113-4.S2CID15414705.

- ^Rutishauser, R (November 1999). "Polymerous leaf whorls in vascular plants: Developmental morphology and fuzziness of organ identities".International Journal of Plant Sciences.160(S6): S81–S103.doi:10.1086/314221.PMID10572024.S2CID4658142.

- ^Stace, C. A.(2019).New Flora of the British Isles(Fourth ed.). Middlewood Green, Suffolk, U.K.: C & M Floristics.ISBN978-1-5272-2630-2.

- ^Gill, Victoria (11 September 2013)."Horsetail plant spores use 'legs' to walk and jump".BBC News.

- ^Zhao, Q.; Gao, J.; Suo, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, T.; Dai, S. (2015)."Cytological and proteomic analyses of horsetail (Equisetum arvense L.) spore germination".Frontiers in Plant Science.6:441.doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00441.PMC4469821.PMID26136760.

- ^Fry, S. C.; Mohler, K. E.; Nesselrode, B. H. W. A.; Frankov, L. (2008)."Mixed-linkage -glucan:xyloglucan endotransglucosylase, a novel wall-remodelling enzyme fromEquisetum(horsetails) and charophytic algae ".The Plant Journal.55(2): 240–252.doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03504.x.PMID18397375.

- ^Fry, Stephen C.; Nesselrode, Bertram H. W. A.; Miller, Janice G.; Mewburn, Ben R. (2008)."Mixed-linkage (1→3,1→4)-β-d-glucan is a major hemicellulose ofEquisetum(horsetail) cell walls ".New Phytologist.179(1): 104–15.doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02435.x.PMID18393951.

- ^Sørensen, Iben; Pettolino, Filomena A.; Wilson, Sarah M.; Doblin, Monika S.; Johansen, Bo; Bacic, Antony; Willats, William G. T. (2008)."Mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan is not unique to the Poales and is an abundant component ofEquisetum arvensecell walls ".The Plant Journal.54(3): 510–21.doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03453.x.PMID18284587.

- ^Simmons, Thomas J.; Fry, Stephen C. (2017)."Bonds broken & formed during the mixed-linkage glucan: xyloglucan endotransglucosylase reaction catalysed by Equisetum hetero-trans-β-glucanase".Biochemical Journal.474(7): 1055–1070.doi:10.1042/BCJ20160935.PMC5341106.PMID28108640.Retrieved2019-07-17.

- ^Pigott, Anthony (4 October 2001)."Summary ofEquisetumTaxonomy ".National Collection of Equisetum.Archived fromthe originalon 21 October 2012.Retrieved17 June2013.

- ^Trounce, Bob; Hanson, Cindy; Lloyd, Sandy; Iaconis, Linda; Thorp, John (2003).Horsetails -Equisetumspecies.Atlas of Living Australia,Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.ISBN1-920932-24-0.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2021-08-26.Retrieved2021-08-26.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^Elgorriaga, Andrés; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Bomfleur, Benjamin; Cúneo, Rubén; Ottone, Eduardo G. (February 2015)."Reconstruction and Phylogenetic Significance of a New Equisetum Linnaeus Species from the Lower Jurassic of Cerro Bayo (Chubut Province, Argentina)".Ameghiniana.52(1): 135–152.doi:10.5710/AMGH.15.09.2014.2758.hdl:11336/66623.ISSN0002-7014.S2CID6134534.

- ^Gould, R. E. 1968. Morphology ofEquisetum lateralePhillips, 1829, andE. bryaniisp. nov. from the Mesozoic of south‐eastern Queensland. Australian Journal of Botany 16: 153–176.

- ^abElgorriaga, Andrés; Escapa, Ignacio H.; Rothwell, Gar W.; Tomescu, Alexandru M. F.; Rubén Cúneo, N. (August 2018)."Origin of Equisetum: Evolution of horsetails (Equisetales) within the major euphyllophyte clade Sphenopsida".American Journal of Botany.105(8): 1286–1303.doi:10.1002/ajb2.1125.PMID30025163.

- ^Channing, Alan; Zamuner, Alba; Edwards, Dianne; Guido, Diego (2011)."Equisetum thermale sp. nov. (Equisetales) from the Jurassic San Agustín hot spring deposit, Patagonia: Anatomy, paleoecology, and inferred paleoecophysiology".American Journal of Botany.98(4): 680–697.doi:10.3732/ajb.1000211.hdl:11336/95234.ISSN1537-2197.PMID21613167.

- ^abcdChristenhusz, Maarten J M; Bangiolo, Lois; Chase, Mark W; Fay, Michael F; Husby, Chad; Witkus, Marika; Viruel, Juan (April 2019). "Phylogenetics, classification and typification of extant horsetails (Equisetum,Equisetaceae) ".Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society.189(4): 311–352.doi:10.1093/botlinnean/boz002.

- ^Nitta, Joel H.; Schuettpelz, Eric; Ramírez-Barahona, Santiago; Iwasaki, Wataru; et al. (2022)."An Open and Continuously Updated Fern Tree of Life".Frontiers in Plant Science.13:909768.doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.909768.PMC9449725.PMID36092417.

- ^"Tree viewer: interactive visualization of FTOL".FTOL v1.4.0 [GenBank release 253]. 2023.Retrieved8 March2023.

- ^Husby, Chad E. (2003)."How large are the giant horsetails?".The Giant Horsetails.Archived fromthe originalon 11 April 2004.Retrieved20 November2008.

- ^Altland, James (2003)."Horsetail - 'Equisetum arvense'".oregonstate.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-11-14.Retrieved2019-07-17.

- ^"Control Horse or Mare's Tail - Equisetum Arvense".Controlling Horsetail with Contact Herbicides.allotment-garden.org.2016.Retrieved2019-07-17.

- ^Kress, Henriette (7 April 2005)."Getting rid of horsetail".Henriette's Herbal Homepage.Retrieved19 May2010.

- ^William Thomas Parsons; Eric George Cuthbertson (2001).Noxious weeds of Australia.CSIRO Publishing. p. 14.ISBN978-0-643-06514-7.

- ^"Equisetum telmateiaEhrh. giant horsetail ".USDA.Retrieved2010-05-18.

- ^"National Pest Plant Accord"(PDF).rnzih.org.nz.2001.Retrieved2019-07-17.

- ^"Equisetum (PFAF Plant Database)".Plants For A Future.

- ^Ashkenazi, Michael; Jacob, Jeanne (2003).Food culture in Japan.Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.ISBN0-313-32438-7.

- ^Turner, Nancy J. (2014). "Appendix 2B. Names of Native Plant Species in Indigenous Languages of Northwestern North America".Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge. Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America(PDF).McGill-Queen’s University Press.ISBN978-0773543805.

- ^Gunther, Erna (1973).Ethnobotany of western Washington: the knowledge and use of indigenous plants by Native Americans(Revised ed.). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.ISBN9780295952581.

- ^Hartford, Robin (25 March 2017)."Is Field Horsetail Edible?".Eatweeds.

- ^abcdefg"Horsetail".Drugs. 11 June 2018.Retrieved19 August2018.

- ^Israelsen, Clark E.; McKendrick, Scott S.; Bagley, Clell V. (2010).Poisonous Plants and Equine(Revised ed.). Logan, UT:Utah State University.p. 6.

- ^abcd"Horsetail".MedlinePlus, US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. 8 December 2017.Retrieved14 November2013.

- ^Henderson JA, Evans EV, McIntosh RA (June 1952). "The antithiamine action ofEquisetum".Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association.120(903): 375–8.PMID14927511.

- ^Fabre, B; Geay, B.; Beaufils, P. (1993). "Thiaminase activity inEquisetum arvenseand its extracts ".Plant Med Phytother.26:190–7.

- ^University of Bonn(12 February 2018)."How Did Huge Dinosaurs Find Enough Food? Did Bacteria Aid Their Digestion?".ScienceDaily.

- ^Williams, Vincent S.; Barrett, Paul M. & Purnell, Mark A. (2009), "Quantitative analysis of dental microwear in hadrosaurid dinosaurs, and the implications for hypotheses of jaw mechanics and feeding",Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,106(27): 11194–11199,Bibcode:2009PNAS..10611194W,doi:10.1073/pnas.0812631106,PMC2708679,PMID19564603

- ^abDragos, D; Gilca, M; Gaman, L; Vlad, A; Iosif, L; Stoian, I; Lupescu, O (2017)."Phytomedicine in Joint Disorders".Nutrients.9(1): 70.doi:10.3390/nu9010070.PMC5295114.PMID28275210.

- ^ab"Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related toEquisetum arvenseL. and invigoration of the body (ID 2437), maintenance of skin (ID 2438), maintenance of hair (ID 2438), maintenance of bone (ID 2439), and maintenance or achievement of a normal body weight (ID 2783) pursuant to Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 ".EFSA Journal.7(10).European Food Safety Authority:1289. 2009.doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1289.

Further reading[edit]

- Husby, Chad E.; Walkowiak, Radosław J. (2012). Zawada, Beth (ed.)."An Introduction to the GenusEquisetum(Horsetail) and the Class Equisetopsida (Sphenopsida) as a whole "(PDF).IEA Paper.International Equisetological Association.

- Weber, Reinhard (June 2005)."Equisetites aequecaliginosussp. nov., ein Riesenschachtelhalm aus der spättriassischen Formation Santa Clara, Sonora, Mexiko "[Equisetites aequecaliginosussp. nov., a giant horsetail from the late Triassic Santa Clara Formation, Sonora, Mexico](PDF).Revue de Paléobiologie(in German and English).24(1). Geneva, Switzerland:Muséum d'histoire naturelle:331–364.ISSN1661-5468.Archived(PDF)from the original on 27 March 2016.Retrieved26 August2021.

- Teichman, Rachel (2021-08-03)."The Ancient (Native) Horsetail: Sometimes Unwelcomed, Always Fascinating! – SSISC".SSISC –Sea to SkyInvasive Species Council.Retrieved2021-08-06.

External links[edit]

- Equisetumat the Tree of Life Web Project

- National Collection ofEquisetum

- International Equisetological Association

- .Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). 1911.