Abdomen

| Abdomen | |

|---|---|

| |

The human abdomen and organs which can be found beneath the surface | |

| Details | |

| Actions | Movement and support for the torso Assistance with breathing Protection for the inner organs Postural support |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | abdomen |

| Greek | ἦτρον |

| MeSH | D000005 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.016 |

| TA2 | 127 |

| FMA | 9577 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Theabdomen(colloquially called thebelly,tummy,midriff,tucky,orstomach[citation needed]) is the front part of thetorsobetween thethorax(chest) andpelvisin humans and in othervertebrates.The area occupied by the abdomen is called theabdominal cavity.Inarthropods,it is theposteriortagmaof the body; it follows the thorax orcephalothorax.[1]

In humans, the abdomen stretches from the thorax at thethoracic diaphragmto the pelvis at thepelvic brim.The pelvic brim stretches from thelumbosacral joint(theintervertebral discbetweenL5andS1) to thepubic symphysisand is the edge of thepelvic inlet.The space above this inlet and under the thoracic diaphragm is termed the abdominal cavity. The boundary of the abdominal cavity is theabdominal wallin the front and the peritoneal surface at the rear.

In vertebrates, the abdomen is a largebody cavityenclosed by the abdominal muscles, at the front and to the sides, and by part of thevertebral columnat the back. Lower ribs can also enclose ventral and lateral walls. The abdominal cavity is continuous with, and above, the pelvic cavity. It is attached to thethoracic cavityby the diaphragm. Structures such as theaorta,inferior vena cavaandesophaguspass through the diaphragm. Both the abdominal and pelvic cavities are lined by a serous membrane known as theparietal peritoneum.This membrane is continuous with thevisceral peritoneumlining the organs.[2]The abdomen in vertebrates contains a number oforgansbelonging to, for instance, thedigestive system,urinary system,andmuscular system.

Contents

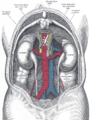

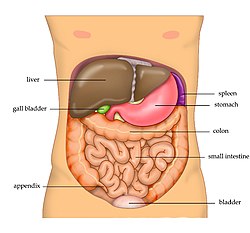

[edit]Theabdominal cavitycontains most organs of thedigestive system,including thestomach,thesmall intestine,and thecolonwith its attachedappendix.Other digestive organs are known as the accessory digestive organs and include theliver,its attachedgallbladder,and thepancreas,and these communicate with the rest of the system via various ducts. Thespleen,and organs of theurinary systemincluding thekidneys,andadrenal glandsalso lie within the abdomen, along with many blood vessels including theaortaandinferior vena cava.Theurinary bladder,uterus,fallopian tubes,andovariesmay be seen as either abdominal organs or as pelvic organs. Finally, the abdomen contains an extensive membrane called theperitoneum.A fold of peritoneum may completely cover certain organs, whereas it may cover only one side of organs that usually lie closer to the abdominal wall. This is called theretroperitoneum,and the kidneys and ureters are known asretroperitonealorgans.

-

View of the various organs and blood-vessels in proximity with liver.

-

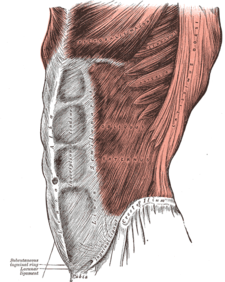

The relations of the viscera and large vessels of the abdomen, seen from behind.

Muscles

[edit](Right) Amaleabdomen.

There are three layers of muscles in theabdominal wall.They are, from the outside to the inside:external oblique,internal oblique,andtransverse abdominal.[3]The first three layers extend between thevertebral column,the lower ribs, theiliac crestandpubisof thehip.All of their fibers merge towards the midline and surround therectus abdominisin a sheath before joining up on the opposite side at thelinea alba.Strength is gained by the criss-crossing of fibers, such that theexternal obliqueruns downward and forward, theinternal obliqueupward and forward, and the transverse abdominal horizontally forward.[3]

Thetransverse abdominalmuscle is flat and triangular, with its fibers running horizontally. It lies between the internal oblique and the underlyingtransverse fascia.It originates from the inguinal ligament, costal cartilages 7-12, the iliac crest and thoracolumbar fascia. Inserts into the conjoint tendon,xiphoid process,linea alba and the pubic crest.

Therectus abdominis musclesare long and flat. The muscle is crossed by three fibrous bands called thetendinous intersections.The rectus abdominis is enclosed in a thick sheath, formed as described above, by fibers from each of the three muscles of the lateral abdominal wall. They originate at thepubis bone,run up the abdomen on either side of the linea alba, and insert into the cartilages of the fifth, sixth, and seventh ribs. In the region of thegroin,theinguinal canal,is a passage through the layers. This gap is where thetestescan drop through the wall and where the fibrous cord from theuterusin the female runs. This is also where weakness can form, and causeinguinal hernias.[3]

Thepyramidalis muscleis small and triangular. It is located in the lower abdomen in front of the rectus abdominis. It originates at the pubic bone and is inserted into the linea alba halfway up to thenavel.

Function

[edit]

Functionally, the human abdomen is where most of the digestive tract is placed and so most of the absorption and digestion of food occurs here. The alimentary tract in the abdomen consists of the loweresophagus,thestomach,theduodenum,thejejunum,ileum,thececumand theappendix,theascending,transverseanddescending colons,thesigmoid colonand therectum.Other vital organs inside the abdomen include theliver,thekidneys,thepancreasand thespleen.

Theabdominal wallis split into the posterior (back), lateral (sides), and anterior (front) walls.

Movement, breathing and other functions

[edit]The abdominal muscles have different important functions. They assist asmuscles of exhalationin the breathing process duringforceful exhalation.Moreover, these muscles serve as protection for the inner organs. Furthermore, together with the back muscles they provide postural support and are important in defining the form. When theglottisis closed and thethoraxandpelvisare fixed, they are integral in thecough,urination,defecation,childbirth,vomit,and singing functions.[3]When the pelvis is fixed, they can initiate the movement of the trunk in a forward motion. They also preventhyperextension.When the thorax is fixed, they can pull up the pelvis and finally, they can bend the vertebral column sideways and assist in the trunk's rotation.[3]

Posture

[edit]The transverse abdominis muscle is the deepest muscle; therefore, it cannot be touched from the outside. It can greatly affect the body's posture. The internal obliques are also deep and also affect body posture. Both of them are involved in rotation and lateral flexion of thespineand are used to bend and support the spine from the front. The external obliques are more superficial and are also involved in rotation and lateral flexion of the spine. They also stabilize the spine when upright. The rectus abdominis muscle is not the most superficial abdominal muscle. The tendonous sheath extending from the external obliques cover the rectus abdominis. The rectus abdominis is the muscle that very fit people develop into "six-pack" abs, though there are five vertical sections on each side. The two bottom sections are just above the pubic bone and usually not visible. The rectus abdominals' function is to bend one's back forward (flexion). The main work of the abdominal muscles is to bend the spine forward when contracting concentrically.[4]

Society and culture

[edit]Social and cultural perceptions of the outward appearance of the abdomen has varying significance around the world. Depending on the type of society,excess weightcan be perceived as an indicator of wealth and prestige due to excess food, or as a sign of poor health due to lack of exercise. In many cultures, bare abdomens are distinctly sexualized and perceived similarly tobreast cleavage.

Exercise

[edit]

Being key elements of spinal support, and contributors to good posture, it is important to properly exercise the abdominal muscles together with the back muscles because when these are weak or overly tight they can suffer painful spasms andinjuries.When properly exercised, abdominal muscles contribute to improved posture and balance, reduce the likelihood ofback painepisodes, reduce the severity of back pain,[6]protect against injury,[7]help avoid some back surgeries, and help with the healing of back problems, or after spine surgery. When strengthened, the abdominal muscles provide flexibility as well. The abdominal muscles can be worked by strength and fitness exercises, and through practicing disciplines of general body strength such asPilates,[8]yoga,[9]tai chi,andjogging.

Clinical significance

[edit]Abdominal obesityis a condition whereabdominal fator visceral fat, has built up excessively between the abdominal organs. This is associated with a higher risk ofheart disease,asthmaandtype 2 diabetes.

Abdominal traumais an injury to the abdomen and can involve damage to the abdominal organs. There is an associated risk ofsevere blood lossandinfection.[10]Injury to the lower chest can cause injuries to the spleen and liver.[11]

A scaphoid abdomen is when the abdomen is sucked inwards.[12]In a newborn, it may represent adiaphragmatic hernia.[13]In general, it is indicative ofmalnutrition.[14]

Disease

[edit]Manygastrointestinal diseasesaffect the abdominal organs. These includestomach disease,liver disease,pancreatic disease,gallbladderandbile ductdisease; intestinal diseases includeenteritis,coeliac disease,diverticulitis,andirritable bowel syndrome.

Examination

[edit]Differentmedical procedurescan be used to examine the organs of the gastrointestinal tract. These includeendoscopy,colonoscopy,sigmoidoscopy,enteroscopy,oesophagogastroduodenoscopyandvirtual colonoscopy.There are also a number ofmedical imagingtechniques that can be used. Surface landmarks are important in theexamination of the abdomen.

Surface landmarks

[edit]

In the mid-line, a slight furrow extends from thexiphoid processabove to thepubic symphysisbelow, representing thelinea albain the abdominal wall. At about its midpoint sits the umbilicus ornavel.Therectus abdominison each side of the linea alba stands out in muscular people. The outline of these muscles is interrupted by three or more transverse depressions indicating thetendinous intersections.There is usually one about the xiphoid process, one at the navel, and one in between. It is the combination of the linea alba and the tendinous intersections which form the abdominal "six-pack" sought after by many people.

The upper lateral limit of the abdomen is the subcostal margin (at or near thesubcostal plane) formed by the cartilages of thefalse ribs(8, 9, 10) joining one another. The lower lateral limit is the anterior crest of theiliumandPoupart's ligament,which runs from the anterior superior spine of the ilium to the spine of thepubis.These lower limits are marked by visible grooves. Just above the pubic spines on either side are the external abdominal rings, which are openings in the muscular wall of the abdomen through which thespermatic cordemerges in the male, and through which aninguinal herniamay rupture.

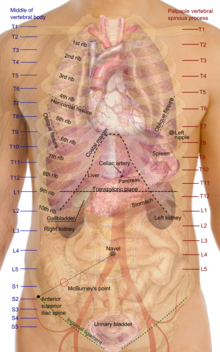

One method by which the location of the abdominal contents can be appreciated is to draw three horizontal and two vertical lines.

Horizontal lines

[edit]

- The highest of the former is thetranspyloric lineof C. Addison, which is situated halfway between thesuprasternal notchand the top of the pubic symphysis, and often cuts the pyloric opening of the stomach an inch to the right of the mid-line. Thehilumof eachkidneyis a little below it, while its left end approximately touches the lower limit of thespleen.It corresponds to the first lumbar vertebra behind.

- The second line is thesubcostal line,drawn from the lowest point of thesubcostal arch(tenth rib). It corresponds to the upper part of the third lumbar vertebra, and it is an inch or so above the umbilicus. It indicates roughly thetransverse colon,the lower ends of the kidneys, and the upper limit of the transverse (3rd) part of theduodenum.

- The third line is called theintertubercular line,and runs across between the two roughtubercles,which can be felt on the outer lip of the crest of the ilium about two and a half inches (64 mm) from the anterior superior spine. This line corresponds to the body of the fifth lumbar vertebra, and passes through or just above theileo-caecal valve,where thesmall intestinejoins thelarge intestine.

Vertical lines

[edit]The two vertical or mid-Poupart lines are drawn from the point midway between the anterior superior spine and the pubic symphysis on each side, vertically upward to the costal margin.

- The right one is the most valuable, as theileo-caecal valveis situated where it cuts the intertubercular line. The orifice of theappendixlies an inch lower, atMcBurney's point.In its upper part, the vertical line meets the transpyloric line at the lower margin of the ribs, usually the ninth, and here thegallbladderis situated.

- The left mid-Poupart line corresponds in its upper three-quarters to the inner edge of thedescending colon.

The right subcostal margin corresponds to the lower limit of theliver,while the right nipple is about half an inch above its upper limit.

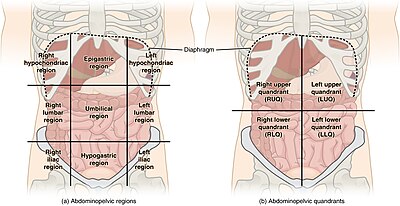

Quadrants and regions

[edit]

The abdomen can be divided into quadrants or regions to describe the location of an organ or structure. Classically, quadrants are described as the left upper, left lower, right upper, and right lower.[citation needed]Quadrants are also often used in describing the site of an abdominal pain.[15]

The abdomen can also be divided into nine regions.

| right hypochondriac/hypochondrium | epigastric/epigastrium | left hypochondriac/hypochondrium |

| right lumbar/flank/latus/lateral | umbilical | left lumbar/flank/latus/lateral |

| rightinguinal/iliac | hypogastric/suprapubic | left inguinal/iliac |

These terms stem from "hypo" meaning "below" and "epi" means "above", while "chondron" means "cartilage" (in this case, the cartilage of the rib) and "gaster" means stomach. The reversal of "left" and "right" is intentional, because the anatomical designations reflectthe patient's own right and left.)

The "right iliac fossa" (RIF) is a common site of pain and tenderness in patients who haveappendicitis.The fossa is named for the underlyingiliac fossaof thehip bone,and thus is somewhat imprecise. Most of the anatomical structures that will produce pain and tenderness in this region are not in fact in the concavity of the ileum. However, the term is in common usage.

Across animal phyla and classes

[edit]Chordata

[edit]Mammals

[edit]Abdominal organs can be highly specialized in some mammals. For example, the stomach ofruminants,(asuborderof mammals that includescattleandsheep), is divided into four chambers –rumen,reticulum,omasumandabomasum.[16]

Arthropoda

[edit]Inarthropods,the abdomen is built up of a series of upper plates known astergitesand lower plates known assternites,the whole being held together by a tough yet stretchable membrane.

Insects

[edit]

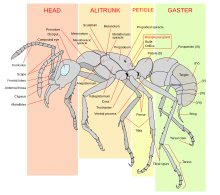

Ininsects,the abdomen contains the insect's digestive tract and reproductive organs, it consists of eleven segments in most orders of insects though the eleventh segment is absent in the adult of most higher orders. The number of these segments does vary from species to species with the number of segments visible reduced to only seven in the commonhoney bee.In theCollembola(springtails), the abdomen has only six segments.

The abdomen is sometimes highly modified. InApocrita(bees, ants and wasps), the first segment of the abdomen is fused to thethoraxand is called thepropodeum.Inants,the second segment forms the narrowpetiole.Some ants have an additionalpostpetiolesegment, and the remaining segments form the bulbousgaster.[17]The petiole and gaster (abdominal segments 2 and onward) are collectively called themetasoma.

Unlike other arthropods, insects possess no legs on the abdomen in adult form, though theProturado have rudimentary leg-like appendages on the first three abdominal segments, andArchaeognathapossess small, articulated "styli" which are sometimes considered to be rudimentary appendages. Many larval insects including theLepidopteraand theSymphyta(sawflies) have fleshy appendages calledprolegson their abdominal segments (as well as their more familiar thoracic legs), which allow them to grip onto the edges of plant leaves as they walk around.

Arachnida

[edit]Inarachnids(spiders, scorpions and relatives), the term "abdomen" is used interchangeably with "opisthosoma"(" hind body "), which is the body section posterior to that bearing the legs and head (the prosoma orcephalothorax).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Abdomen.Dictionary. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th Edition. Retrieved 22 October 2007

- ^Peritoneum.The Veterinary Dictionary. Elsevier, 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007

- ^abcde"Abdominal cavity".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. I: A-Ak – Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL. 2010. pp.19–20.ISBN978-1-59339-837-8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"The Abdominal Muscle Group".Archived fromthe originalon 2015-12-26.Retrieved2010-07-13.

- ^Terry, Michael; Goodman, Paul (2019).Hockey Anatomy.Champaign: Human Kinetics. pp. 74–75.ISBN978-1-4925-3588-1.

- ^Raj, Joshua (2011).A Guide to the Prevention and Treatment of Back Pain.Singapore: Armour. p. 23.ISBN978-981-4305-32-7.

- ^Reger-Nash, Bill; Smith, Meredith; Juckett, Gregory (2015).Foundations of Wellness.Human Kinetics. p. 96.ISBN978-1-4504-0200-2.

- ^Isacowitz, Rael (2014).Pilates(2 ed.). Champaign: Human Kinetics. p. 36.ISBN978-1-4504-3416-4.

- ^Swenson, Doug (2001). "Accumulating strong abs".Power Yoga for Dummies.Hoboken: Wiley Publishers.

- ^Jansen JO, Yule SR, Loudon MA (April 2008)."Investigation of blunt abdominal trauma".BMJ.336(7650): 938–42.doi:10.1136/bmj.39534.686192.80.PMC2335258.PMID18436949.

- ^Wyatt, Jonathon; Illingworth, RN; Graham, CA; Clancy, MJ; Robertson, CE (2006).Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine.Oxford University Press. p. 346.ISBN978-0-19-920607-0.

- ^Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary(32nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. 2012. p. 2.ISBN978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^Durward, Heather; Baston, Helen (2001).Examination of the newborn: a practical guide.New York: Routledge. p.134.ISBN978-0-415-19184-5.

- ^Ferguson, Charles (1990)."Inspection, Auscultation, Palpation, and Percussion of the Abdomen".In Walker, HK; Hall, WD; Hurst, JW (eds.).Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations(3rd ed.). Boston: Butterworths.ISBN9780409900774.Retrieved2013-11-27.

- ^Saladin, Kenneth (2011).Human anatomy.McGraw-Hill. p. 14.ISBN9780071222075.

- ^"Ruminant."The Veterinary Dictionary. Elsevier, 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007

- ^"Glossary of Descriptive Terminology".Desertants.org. Archived fromthe originalon 17 May 2013.Retrieved2013-07-08.

External links

[edit]- .Collier's New Encyclopedia.1921.

Media related toAbdomenat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toAbdomenat Wikimedia Commons