Indian nationalism

This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Indian nationalismis an instance ofterritorial nationalism,which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite theirdiverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds.Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, but was fully developed during theIndian independence movementwhich campaigned forindependencefromBritish rule.Indian nationalism quickly rose to popularity in India through these united anti-colonial coalitions and movements. Independence movement figures likeMahatma Gandhi,Subhas Chandra Bose,andJawaharlal Nehruspearheaded the Indian nationalist movement. AfterIndian Independence,Nehru and his successors continued to campaign on Indian nationalism in face of border wars with bothChinaandPakistan.After theIndo-Pakistan War of 1971and theBangladesh Liberation War,Indian nationalism reached its post-independence peak. However by the 1980s, religious tensions reached amelting pointand Indian nationalism sluggishly collapsed in the following decades. Despite its decline and the rise of religious nationalism, Indian nationalism and its historic figures continue to strongly influence thepolitics of Indiaand reflect an opposition to the sectarian strands ofHindu nationalismandMuslim nationalism.[1][2][3][4]

National consciousness in India

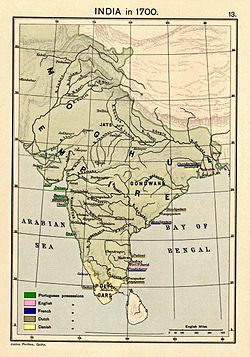

Among antient texts, the Indian subcontinent came to be called Bharat under the rule ofBharata.[5]TheMaurya Empirewas the first to unite all ofIndia,and South Asia (including parts ofAfghanistan).[6]Much of India has also been unified by later empires, such as theMughal Empire,[7]Maratha Empire.[8]

Conception of Pan-South Asianism

India's concept of nationhood is based not merely on territorial extent of its sovereignty. Nationalistic sentiments and expression encompass that India's ancient history,[9]as the birthplace of theIndus Valley civilisation,as well as four major world religions –Hinduism,Buddhism,JainismandSikhism.Indian nationalists see India stretching along these lines across theIndian subcontinent.[citation needed]

Ages of war and invasion

India today celebrates many kings and queens for combating foreign invasion and domination,[10]such asShivajiof theMaratha Empire,RaniLaxmibaiofJhansi,Kittur Chennamma,Maharana PratapofRajputana,Prithviraj ChauhanandTipu Sultan.The kings ofAncient India,such asChandragupta MauryaandAshokaof theMagadhaEmpire, are also remembered for their military genius, notable conquests and remarkablereligious tolerance.

Akbarwas a Mughal emperor, was known to have a good relationship with the Roman Catholic Church as well as with his subjects – Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains.[10]He forged familial and political bonds with HinduRajputkings. Although previous Sultans had been more or less tolerant, Akbar took religious intermingling to new level of exploration. He developed for the first time in Islamic India an environment of complete religious freedom. Akbar undid most forms of religious discrimination, and invited the participation of wise Hindu ministers and kings, and even religious scholars to debate in his court.[11]

Colonial-era nationalism

The consolidation of theBritish East India Company's rule in the Indian subcontinent during the 18th century brought about socio-economic changes which led to the rise of an Indianmiddle classand steadily eroded pre-colonial socio-religious institutions and barriers.[12]The emerging economic and financial power of Indian business-owners and merchants and the professional class brought them increasingly into conflict with the British authorities. A rising political consciousness among the native Indian social elite (including lawyers, doctors, university graduates, government officials and similar groups) spawned an Indian identity[13][14]and fed a growing nationalist sentiment in India in the last decades of the nineteenth century.[15]The creation in 1885 of theIndian National Congressin India by the political reformerA.O. Humeintensified the process by providing an important platform from which demands could be made for political liberalisation, increased autonomy, and social reform.[16]The leaders of the Congress advocated dialogue and debate with the Raj administration to achieve their political goals. Distinct from these moderate voices (or loyalists) who did not preach or support violence was the nationalist movement, which grew particularly strong, radical and violent inBengaland inPunjab.Notable but smaller movements also appeared inMaharashtra,Madrasand other areas across the south.[16]

Swadeshi

The controversial1905 partition of Bengalescalated the growing unrest, stimulating radical nationalist sentiments and becoming a driving force for Indian revolutionaries.[17]

The Gandhian era

Mahatma Gandhipioneered the art ofSatyagraha,typified with a strict adherence toahimsa(non-violence), andcivil disobedience.This permitted common individuals to engage the British in revolution, without employing violence or other distasteful means. Gandhi's equally strict adherence to democracy, religious and ethnic equality and brotherhood, as well as activist rejection of caste-based discrimination anduntouchabilityunited people across these demographic lines for the first time in India's history. The masses participated in India's independence struggle for the first time, and the membership of the Congress grew over tens of millions by the 1930s. In addition, Gandhi's victories in theChamparanandKhedaSatyagraha in 1918–19, gave confidence to a rising younger generation of Indian nationalists that India could gain independence from British rule. National leaders likeMahatma Gandhi,Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel,Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru,Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose,Maulana Azad,Chakravarti Rajagopalachari,Rajendra PrasadandKhan Abdul Gaffar Khanbrought together generations of Indians across regions and demographics, and provided a strong leadership base giving the country political direction.

Beyond Indian nationalism

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(March 2019) |

Indian nationalism is as much a diverse blend of nationalistic sentiments as its people are ethnically and religiously diverse. Thus the most influential undercurrents are more than justIndianin nature. The most controversial and emotionally charged fibre in the fabric of Indian nationalism is religion. Religion forms a major, and in many cases, the central element of Indian life. Ethnic communities are diverse in terms of linguistics, social traditions and history across India.[18]

Hindu Rashtra

An important influence upon Hindu consciousness arises from the time ofIslamic empires in India.Entering the 20th century, Hindus formed over 75% of the population and thus unsurprisingly the backbone and platform of the nationalist movement. Modern Hindu thinking desired to unite Hindu society across the boundaries ofcaste,linguistic groups and ethnicity. In 1925,K.B. Hedgewarfounded theRashtriya Swayamsevak SanghinNagpur,Maharashtra, which grew into the largest civil organisation in the country, and the most potent, mainstream base ofHindu nationalism.[19]

Vinayak Damodar Savarkarcoined the termHindutvafor his ideology that described India as aHindu Rashtra,a Hindu nation. This ideology has become the cornerstone of the political and religious agendas of modern Hindu nationalist bodies like theBharatiya Janata Partyand theVishwa Hindu Parishad.Hindutva political demands include revoking Article 370 of the Constitution that grants a special semi-autonomous status to the Muslim-majority state ofKashmir,adopting a uniform civil code, thus ending a special legal frameworks for different religions in the country.[20]These particular demands are based upon ending laws that Hindu nationalists consider to be special treatment offered to different religions.[21]

The Qaum

In 1906–1907, theAll-India Muslim Leaguewas founded, created due to the suspicion of Muslim intellectuals and religious leaders with theIndian National Congress,which was perceived as dominated by Hindu membership and opinions. However,Mahatma Gandhi's leadership attracted a wide array of Muslims to the independence struggle and the Congress Party. TheAligarh Muslim Universityand theJamia Millia Islamiastand apart – the former helped form the Muslim league, while the JMI was founded to promote Muslim education and consciousness upon nationalistic and Gandhian values and thought.

While prominent Muslims likeAllama Iqbal,Muhammad Ali JinnahandLiaquat Ali Khanembraced the notion that Hindus and Muslims were distinct nations, other major leaders likeMukhtar Ahmed Ansari,Maulana Azadand most ofDeobandiclerics strongly backed the leadership ofMahatma Gandhiand the Indian independence struggle, opposing any notion ofMuslim nationalism and separatism.The Muslim school of Indian nationalism failed to attract Muslim masses and theIslamic nationalistMuslim Leagueenjoyed extensive popular political support. Thestate of Pakistanwas ultimately formed following thePartition of India.

Views on the partition of India

Indian nationalists led byMohandas Karamchand GandhiandJawaharlal Nehruwanted to make what was then British India, as well as the 562 princely states under British paramountcy, into a single secular, democratic state.[22]TheAll India Azad Muslim Conference,which represented nationalist Muslims, gathered in Delhi in April 1940 to voice its support for anindependent and united India.[23]The British Government, however, sidelined the 'All India' organization from the independence process and came to see Jinnah, who advocated separatism, as the sole representative of Indian Muslims.[24]This was viewed with dismay by many Indian nationalists, who viewed Jinnah's ideology as damaging and unnecessarily divisive.[25]

In an interview withLeonard Mosley,Nehru said that he and his fellow Congressmen were "tired" after the independence movement, so were not ready to further drag on the matter for years with Jinnah's Muslim League, and that, anyway, they "expected that partition would be temporary, that Pakistan would come back to us."[26]Gandhi also thought that the Partition would be undone.[27]TheAll India Congress Committee,in a resolution adopted on 14 June 1947, openly stated that "geography and the mountains and the seas fashioned India as she is, and no human agency can change that shape or come in the way of its final destiny... at when present passions have subsided, India's problems will be viewed in their proper perspective and the false doctrine of two nations will be discredited and discarded by all."[28]V.P. Menon,who had an important role in the transfer of power in 1947, quotes another major Congress politician,Abul Kalam Azad,who said that "the division is only of the map of the country and not in the hearts of the people, and I am sure it is going to be a short-lived partition."[29]Acharya Kripalani,President of the Congress during the days of Partition, stated that making India "a strong, happy, democratic and socialist state" would ensure that "such an India can win back the seceding children to its lap... for the freedom we have achieved cannot be complete without the unity of India."[30]Yet another leader of the Congress,Sarojini Naidu,said that she did not consider India's flag to be India's because "India is divided" and that "this is merely a temporary geographical separation. There is no spirit of separation in the heart of India."[31]

Giving a more general assessment,Paul Brasssays that "many speakers in theConstituent Assemblyexpressed the belief that theunity of India would be ultimately restored."[32]

See also

References

- ^Lerner, Hanna (12 May 2011),Making Constitutions in Deeply Divided Societies,Cambridge University Press, pp. 120–,ISBN978-1-139-50292-4

- ^Jaffrelot, Christophe (1999),The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s: Strategies of Identity-building, Implantation and Mobilisation (with Special Reference to Central India),Penguin Books India, pp. 13–15, 83,ISBN978-0-14-024602-5

- ^Pachuau, Lalsangkima; Stackhouse, Max L. (2007),News of Boundless Riches,ISPCK, pp. 149–150,ISBN978-81-8458-013-6

- ^Leifer, Michael (2000),Asian Nationalism,Psychology Press, pp. 112–,ISBN978-0-415-23284-5

- ^Vyasa, Dwaipayana (24 August 2021).The Mahabharata of Vyasa: (Complete 18 Volumes).Enigma Edizioni. p. 2643.

- ^Afghanistan Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments geredigeerd door Inb, Inc.International Business Publications, USA. 10 September 2013.ISBN9781438773728.Retrieved27 February2015.[dead link]

- ^Vyasa, Dwaipayana (24 August 2021).The Mahabharata of Vyasa: (Complete 18 Volumes).Enigma Edizioni. p. 2643.

- ^Davies, Cuthbert Collin (1959).An Historical Atlas of the Indian Peninsula.Oxford University Press. p. 54.ISBN978-0-19-635139-1.

- ^Acharya, Shiva."Nation, Nationalism and Social Structure in Ancient India By Shiva Acharya".Sundeepbooks. Archived fromthe originalon 15 February 2012.Retrieved17 November2011.

- ^ab"Mahrattas, Sikhs and Southern Sultans of India: Their Fight Against Foreign Power/edited by H.S. Bhatia".Vedamsbooks.Retrieved17 November2011.

- ^Lane-Poole, Stanley. Jackson, A. V. Williams (ed.).History of India.London: Grolier society. pp. 26-.

- ^Mitra 2006,p. 63

- ^Croitt & Mjøset 2001,p. 158

- ^Desai 2005,p. xxxiii

- ^Desai 2005,p. 30

- ^abYadav 1992,p. 6

- ^Bose & Jalal 1998,p. 117

- ^Lobo, Lancy (2002).Globalisation, Hindu nationalism, and Christians in India.Jaipur: Rawat Publications. p. 26.ISBN978-81-7033-716-4.

- ^"Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh | History, Ideology, & Facts".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved28 July2020.

- ^"What is Uniform Civil Code?".Jagranjosh.7 August 2019.Retrieved28 July2020.

- ^"WHAT IS UNIFORM CIVIL CODE".Business Standard.Retrieved28 July2020.

- ^Hardgrave, Robert."India: The Dilemmas of Diversity",Journal of Democracy,pp. 54–65

- ^Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017).Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan.Cambridge University Press. p. 2.ISBN9781108621236.

- ^Qaiser, Rizwan (2005), "Towards United and Federate India: 1940-47",Maulana Abul Kalam Azad a study of his role in Indian Nationalist Movement 1919–47,Jawaharlal Nehru University/Shodhganga, Chapter 5, pp. 193, 198,hdl:10603/31090

- ^Raj Pruthi,Paradox of Partition: Partition of India and the British strategy,Sumit Enterprises (2008), p. 444

- ^Sankar Ghose,Jawaharlal Nehru, a Biography,Allied Publishers (1993), pp. 160-161

- ^Raj Pruthi,Paradox of Partition: Partition of India and the British strategy,Sumit Enterprises (2008), p. 443

- ^Graham Chapman,The Geopolitics of South Asia: From Early Empires to the Nuclear Age,Ashgate Publishing (2012), p. 326

- ^V.P. Menon,The Transfer of Power in India,Orient Blackswan (1998), p. 385

- ^G. C. Kendadamath,J.B. Kripalani, a study of his political ideas,Ganga Kaveri Pub. House (1992), p. 59

- ^Constituent Assembly Debates: Official Report,Volume 4, Lok Sabha secretariat, 14 July 1947, p. 761

- ^Paul R. Brass,The Politics of India Since Independence,Cambridge University Press (1994), p. 10

Bibliography

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (1998),Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy,New York: Routledge,ISBN0-415-16952-6

- Croitt, Raymond D; Mjøset, Lars (2001),When Histories Collide,Oxford, UK: AltaMira,ISBN0-7591-0158-2

- Desai, A.R. (2005),Social Background of Indian Nationalism (6Th-Edn),Popular Prakashan,ISBN978-81-7154-667-1

- Mitra, Subrata K. (2006),The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory,Routledge,ISBN978-1-134-27493-2

- Mukherjee, Bratindra Nath(2001),Nationhood and Statehood in India: A historical survey,Regency Publications,ISBN978-81-87498-26-1

- Yadav, B.D (1992),M.P.T. Acharya, Reminiscences of an Indian Revolutionary,New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt ltd,ISBN81-7041-470-9

External links

Media related toIndian nationalismat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toIndian nationalismat Wikimedia Commons