Indo-Roman trade relations

Indo-Roman trade relations(see also thespice tradeandincense road) was trade between theIndian subcontinentand theRoman EmpireinEuropeand theMediterranean Sea.Trade through the overland caravan routes viaAsia Minorand theMiddle East,though at a relative trickle compared to later times, preceded the southern trade route via theRed Seawhich started around the beginning of theCommon Era(CE) following the reign ofAugustusandhis conquestofEgyptin 30 BCE.[1]

The southern route so helped enhance trade between the ancientRoman Empireand the Indian subcontinent, that Roman politicians and historians are on record decrying the loss of silver and gold to buy silk to pamper Roman wives, and the southern route grew to eclipse and then totally supplant the overland trade route.[2]Roman and Greek traders frequented theancient Tamil country,present daySouthern IndiaandSri Lanka,securing trade with the seafaringTamilstates of thePandyan,CholaandCheradynasties andestablishing trading settlementswhich secured trade with the Indian subcontinent by theGreco-Roman worldsince the time of thePtolemaic dynasty[3]a few decades before the start of theCommon Eraand remained long after the fall of theWestern Roman Empire.[4]

Background

[edit]

TheSeleucid dynastycontrolled a developed network of trade with theIndian Subcontinentwhich had previously existed under the influence of theAchaemenid Empire.The Greek-Ptolemaic dynasty,controlling the western and northern end of other trade routes toSouthern Arabiaand the Indian Subcontinent,[5]had begun to exploit trading opportunities in the region prior to the Roman involvement but, according to the historianStrabo,the volume of commerce between Indians and the Greeks was not comparable to that of later Indo-Roman trade.[2]

ThePeriplus Maris Erythraeimentions a time when sea trade between Egypt and the subcontinent did not involve direct sailings.[2]The cargo under these situations was shipped toAden:[2]

Aden – Arabia Eudaimon was called the fortunate, being once a city, when, because ships neither came from India toEgyptnor did those from Egypt dare to go further but only came as far as this place, it received the cargoes from both, just asAlexandriareceives goods brought from outside and from Egypt.

— Gary Keith Young, Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy

The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with Indian kingdoms using the Red Sea ports.[1]With the establishment ofRoman Egypt,the Romans took over and further developed the already existing trade using these ports.[1]

Classical geographers such asStraboandPliny the Elderwere generally slow to incorporate new information into their works and, from their positions asesteemed scholars,were seemingly prejudiced against lowly merchants and theirtopographicalaccounts.[6]Ptolemy'sGeographyrepresents somewhat of a break from this since he demonstrated an openness to their accounts and would not have been able to chart theBay of Bengalso accurately had it not been for the input of traders.[6]It is perhaps no surprise then that Marinus and Ptolemy relied on the testimony of a Greek sailor named Alexander for how to reach "Cattigara"(most likelyOc Eo,Vietnam,whereAntonine-periodRoman artefactshave been discovered) in theMagnus Sinus(i.e.Gulf of ThailandandSouth China Sea) located east of theGolden Chersonese(i.e.Malay Peninsula).[7][8]In the 1st-century CEPeriplus of the Erythraean Sea,its anonymous Greek-speaking author, a merchant ofRoman Egypt,provides such vivid accounts of trade cities in Arabia and India, includingtravel times from rivers and towns,where to dropanchor,the locations of royal courts, lifestyles of the locals and goods found in their markets, and favorable times of year to sail from Egypt to these places in order to catch themonsoonwinds, that it is clear he visited many of these locations.[9]

Establishment

[edit]

The replacement of Greek kingdoms by the Roman Empire as the administrator of the easternMediterraneanbasin led to the strengthening of direct maritime trade with the east and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of various land based trading routes.[10]Strabo'smention of the vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt indicates that monsoon was known from his time.[11]

The trade started byEudoxus of Cyzicusin 130 BCE kept increasing according to Strabo (II.5.12.):[12]

At any rate, whenGalluswas prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended theNileas far asSyeneand the frontiers ofKingdom of Aksum(Ethiopia), and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing fromMyos Hormosto the subcontinent, whereas formerly, under thePtolemies,only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise.

— Strabo

By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships were setting sail every year fromMyos Hormosto India.[12]So much gold was used for this trade, and apparently recycled by theKushan Empire(Kushans) for their own coinage, thatPliny the Elder(NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:

India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred millionsestercesfrom our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what fraction of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?

— Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

-

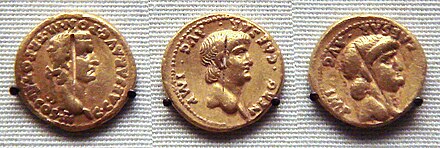

Gold coin ofClaudius(50–51 CE) excavated in South India.

-

Gold coin ofJustinian I(527–565 CE) excavated in India probably in the south.

Trade of exotic animals

[edit]

There is evidence of animal trade between Indian Ocean harbours and theMediterranean.This can be seen in themosaicsandfrescoesof the remains ofRoman villasinItaly.For example, theVilla del Casalehas mosaics depicting the capture of animals in India, Indonesia and Africa. The intercontinental trade of animals was one of the sources of wealth for the owners of the villa. In theAmbulacro della Grande Caccia,[13]the hunting and capture of animals is represented in such detail that it is possible to identify the species. There is a scene that shows a technique to distract atigerwith a shimmering ball ofglassormirrorin order to take her cubs. Tiger hunting with red ribbons serving as a distraction is also shown. In the mosaic there are also numerous other animals such asrhinoceros,anIndian elephant(recognized from the ears) with his Indian conductor, and theIndian peafowl,and other exotic birds. There are also numerous animals fromAfrica.Tigers,leopardsand Asian and Africanlionswere used in thearenasandcircuses.TheEuropean lionwas already extinct at that time. Probably the last lived in theBalkan Peninsulaand were hunted to stock arenas. The birds and monkeys entertained the guests of many villas. Also in theVilla Romana del Tellarothere is a mosaic with a tiger in the jungle attacking a man with Roman clothes, probably a careless hunter. The animals were transported in cages by ship.[14]

Ports

[edit]Roman ports

[edit]The three main Roman ports involved with eastern trade wereArsinoe,Bereniceand Myos Hormos. Arsinoe was one of the early trading centers but was soon overshadowed by the more easily accessible Myos Hormos and Berenice.

Arsinoe

[edit]

The Ptolemaic dynasty exploited the strategic position ofAlexandriato secure trade with the subcontinent.[3]The course of trade with the east then seems to have been first through the harbor of Arsinoe, the present daySuez.[3]The goods from theEast Africantrade were landed at one of the three main Roman ports, Arsinoe, Berenice or Myos Hormos.[15]The Romans repaired and cleared out the silted up canal from the Nile to harbor center of Arsinoe on the Red Sea.[16]This was one of the many efforts the Roman administration had to undertake to divert as much of the trade to the maritime routes as possible.[16]

Arsinoe was eventually overshadowed by the rising prominence of Myos Hormos.[16]The navigation to the northern ports, such as Arsinoe-Clysma, became difficult in comparison to Myos Hormos due to the northern winds in theGulf of Suez.[17]Venturing to these northern ports presented additional difficulties such asshoals,reefsand treacherouscurrents.[17]

Myos Hormos and Berenice

[edit]

Myos Hormos and Berenice appear to have been important ancient trading ports, possibly used by thePharaonictraders of ancient Egypt and the Ptolemaic dynasty before falling into Roman control.[1]

The site of Berenice, since its discovery byBelzoni(1818), has been equated with the ruins nearRas Banasin Southern Egypt.[1]However, the precise location of Myos Hormos is disputed with the latitude and longitude given inPtolemy'sGeographyfavoring Abu Sha'ar and the accounts given inclassical literatureandsatellite imagesindicating a probable identification with Quseir el-Quadim at the end of a fortified road fromKoptoson theNile.[1]The Quseir el-Quadim site has further been associated with Myos Hormos following the excavations atel-Zerqa,halfway along the route, which have revealedostracaleading to the conclusion that the port at the end of this road may have been Myos Hormos.[1]

In Berenike in March 2022 an American-Polish archaeological mission excavating the main early Roman period temple dedicated to theGoddess Isisuncovered in the forecourt of the temple a marble statue of aBuddha,theBerenike Buddha,suggesting the presence of Buddhist merchants from India in Egypt at that time.[18][19]

Major regional ports

[edit]

The regional ports ofBarbaricum(modernKarachi),Sounagoura(centralBangladesh),Barygaza(Bharuch inGujarat),Muziris(present dayKodungallur),Korkai,KaveripattinamandArikamedu(Tamil Nadu) on the southern tip of present-day India were the main centers of this trade, along withKodumanal,an inland city. ThePeriplus Maris Erythraeidescribes Greco-Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens,topaz,coral,storax,frankincense,vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine "in exchange for"costus,bdellium,lycium,nard,turquoise,lapis lazuli,Seric skins,cotton cloth,silkyarn, andindigo".[20]In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth.[20]

Barigaza

[edit]Trade with Barigaza, under the control of theIndo-ScythianWestern SatrapNahapana( "Nambanus" ), was especially flourishing:[20]

There are imported into this market-town (Barigaza), wine, Italian preferred, also Laodicean and Arabian; copper, tin, and lead; coral and topaz; thin clothing and inferior sorts of all kinds; bright-coloredgirdlesa cubit wide; storax,sweetclover,flint glass,realgar,antimony,gold and silver coin, on which there is a profit when exchanged for the money of the country; and ointment, but not very costly and not much. And for the King there are brought into those places very costly vessels of silver, singing boys, beautiful maidens for the harem, fine wines, thin clothing of the finest weaves, and the choicest ointments. There are exported from these placesspikenard,costus,bdellium,ivory,agateandcarnelian,lycium,cotton cloth of all kinds,silkcloth, mallow cloth, yarn,long pepperand such other things as are brought here from the various market-towns. Those bound for this market-town from Egypt make the voyage favorably about the month of July, that is Epiphi.

— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (paragraph 49).

Muziris

[edit]

Muzirisis a lost port city on the south-western coast of India which was a major center of trade in the ancient Tamil land between the Chera kingdom and the Roman Empire.[21]Its location is generally identified with modern-dayCranganore(central Kerala).[22][23]Large hoards of coins and innumerable shards ofamphoraefound at the town ofPattanam(near Cranganore) have elicited recent archeological interest in finding a probable location of this port city.[21]

According to thePeriplus,numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:[20]

Then come Naura and Tyndis, the first markets ofDamirica(Limyrike), and then Muziris and Nelcynda, which are now of leading importance. Tyndis is of theKingdom of Cerobothra;it is a village in plain sight by the sea. Muziris, of the same Kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by river and sea five hundred stadia, and up the river from the shore twenty stadia "

— The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (53–54)

Arikamedu

[edit]ThePeriplus Maris Erythraeimentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), whichG.W.B. Huntingfordidentified as possibly beingArikameduinTamil Nadu,a centre ofearly Cholatrade (now part ofAriyankuppam), about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the modernPondicherry.[24]Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery was found at Arikamedu in 1937, andarcheologicalexcavations between 1944 and 1949 showed that it was "a trading station to which goods of Roman manufacture were imported during the first half of the 1st century AD".[24]

Cultural exchanges

[edit]

The Rome-subcontinental trade also saw several cultural exchanges which had a lasting effect on both the civilizations and others involved in the trade. TheEthiopiankingdom ofAksumwas involved in the Indian Ocean trade network and was influenced by Roman culture and Indian architecture.[4]Traces of Indian influences are visible in Roman works of silver and ivory, or in Egyptian cotton and silk fabrics used for sale inEurope.[25]The Indian presence in Alexandria may have influenced the culture but little is known about the manner of this influence.[25]Clement of Alexandriamentions theBuddhain his writings and otherIndian religionsfind mentions in other texts of the period.[25]

Han Chinawas perhaps alsoinvolved in the Roman trade,withRoman embassiesrecorded for the years 166, 226, and 284 that allegedly landed inRinan(Jiaozhi) in northernVietnam,according toChinese histories.[7][26][27][28]Roman coinsand goodssuch as glasswaresandsilverwareshave been found in China,[29][30]as well as Roman coins, bracelets, glass beads, a bronze lamp, andAntonine-period medallions in Vietnam, especially atOc Eo(belonging to theFunan Kingdom).[7][26][31]The 1st-centuryPeriplusnotes how a country calledThis,with a great city calledThinae(comparable toSinaeinPtolemy'sGeography),produced silkand exported it toBactriabefore it traveled overland toBarygazain India and down theGanges River.[32]WhileMarinus of TyreandPtolemyprovided vague accounts of theGulf of ThailandandSoutheast Asia,[33]the Alexandrian Greek monk and former merchantCosmas Indicopleustes,in hisChristian Topography(c. 550), spoke clearly about China, how to sail there, and how it was involved in theclovetrade stretching toCeylon.[34][35]Comparing the small amount of Roman coins found in China as opposed to India,Warwick Ballasserts that most of the Chinesesilkpurchased by the Romans was done so in India, withthe land routethroughancient Persiaplaying a secondary role.[36]

ChristianandJewishsettlers from Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.[4]Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.[4]TheTamilakkamkings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins in order to signify their sovereignty.[37]Mentions of the traders are recorded in theTamilSangam literatureof India.[37]One such mention reads: "The beautifully built ships of the Yavanas came with gold and returned with pepper, and Muziris resounded with the noise." (from poem no. 149 of 'Akananuru' of Sangam Literature) "[37]

Decline and aftermath

[edit]Roman decline

[edit]

Trade declined from the mid-3rd century duringa crisis in the Roman Empire,but recovered in the 4th century until the early 7th century, whenKhosrow II,Shah of theSasanian Empire,occupied the Roman parts of the Fertile Crescent and Egyptuntilbeing defeatedby theEastern Roman EmperorHeraclius[38]at the end of 627, after which the lost territories were returned to the Eastern Romans.Cosmas Indicopleustes('Cosmas who sailed to India') was a Greek-Egyptian trader, and later monk, who wrote about his trade trips to India and Sri Lanka in the 6th century.

Ravaging of the Gupta Empire by the Huns

[edit]

TheGupta Empirehad been benefiting greatly from Indo-Roman trade. They had been exporting numerous luxury products such assilk,leather goods, fur, iron products,ivory,pearlor pepper from the ports ofBharutkutccha,Kalyan,Sindand the city ofUjjaini.[42]

TheAlchon Huns' invasions (496–534 CE) are said to have seriously damaged the Gupta's (c.319-560 CE) trade withEuropeandCentral Asia.[43]Soon after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by these invasions and the rise of local rulers, ended as well.[44]Following the invasions, northern India was left in disarray, with numerous smaller Indian powers emerging after the crumbling of the Guptas.[45]

Arab expansion

[edit]

The Arabs, led by'Amr ibn al-'As,crossed into Egypt in late 639 or early 640 CE.[46]This advance marked the beginning of theIslamic conquest of Egypt.[46]The capture of Alexandria and the rest of the country[47]brought an end to 670 years of Roman trade with the subcontinent.[3]

Tamil speaking south India turned toSoutheast Asiafor international trade where Indian cultureinfluenced the native cultureto a greater degree than the sketchy impressions made on Rome seen in the adoption ofHinduismand then Buddhism.[48]However, knowledge of the Indian subcontinent and its trade was preserved in Byzantine books and it is likely that the court of the Emperor still maintained some form of diplomatic relation to the region up until at least the time ofConstantine VII,seeking an ally against the rising influence of the Islamic states in the Middle East and Persia, appearing in a work on ceremonies calledDe Ceremoniis.[49]

TheOttoman TurksconqueredConstantinoplein the 15th century (1453), marking the beginning of Turkish control over the most direct trade routes between Europe and Asia.[50]The Ottomans initially cut off eastern trade with Europe, leading in turn to the attempt by Europeans to find a sea route around Africa, spurring the EuropeanAge of Discovery,and the eventual rise of EuropeanMercantilismandColonialism.

See also

[edit]- Ancient Greece–Ancient India relations

- Buddhism and the Roman world

- Chronology of European exploration of Asia

- Economic history of India

- Historic GDP of India (1-1947 CE)

- Indus–Mesopotamia relations

- Indian maritime history

- Indo-Mediterranean

- Indo-Roman relations

- Maritime Silk Road

- Meluhha trade with Sumer

- Sino-Roman relations

Notes

[edit]- ^abcdefgShaw 2003: 426

- ^abcdYoung 2001: 19

- ^abcdLindsay 2006: 101

- ^abcdCurtin 1984: 100

- ^Potter 2004: 20

- ^abParker 2008: 118.

- ^abcYoung 2001: 29.

- ^Mawer 2013: 38.

- ^William H. Schoff (2004) [1912]. Lance Jenott (ed.).""The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century" in The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea ".Depts.washington.edu.University of Washington.Retrieved19 September2016.

- ^Lach 1994: 13

- ^Young 2001: 20

- ^ab"The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917".

- ^"Archived copy".Archived from the original on 13 February 2017.Retrieved19 February2011.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^"Il Blog sulla Villa Romana del Casale Piazza Armerina".villadelcasale.it.Retrieved12 February2017.

- ^O'Leary 2001: 72

- ^abcFayle 2006: 52

- ^abFreeman 2003: 72

- ^"Garum Masala;Dramatic archaeological discoveries have led scholars to radically reassess the size and importance of the trade between ancient Rome and India".New York Review.20 April 2023.

- ^Magazine, Smithsonian; Parker, Christopher."Archaeologists Unearth Buddha Statue in Ancient Egyptian Port City".Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^abcdHalsall, Paul."Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century".Fordham University.

- ^ab"Search for India's ancient city".BBC. 11 June 2006.Retrieved4 January2010.

- ^George Menachery (1987)Kodungallur City of St. Thomas;(2000)Azhikode alias Kodungallur Cradle of Christianity in India

- ^"Signs of ancient port in Kerala".telegraphindia.Calcutta (Kolkata): The Telegraph. Archived fromthe originalon 4 August 2009.Retrieved12 February2017.

- ^abHuntingford 1980: 119.

- ^abcLach 1994: 18

- ^abBall 2016: 152–53

- ^Hill 2009: 27

- ^Yule 1915: 53–54

- ^An 2002: 83

- ^Harper 2002: 99–100, 106–07

- ^O'Reilly 2007: 97

- ^Schoff 2004 [1912]:paragraph #64.Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^Suárez (1999): 90–92

- ^Yule 1915: 25–28

- ^Lieu 2009: 227

- ^Ball 2016: 153–54.

- ^abcKulke 2004: 108

- ^Farrokh 2007: 252

- ^Bakker, Hans (2017).Monuments of Hope, Gloom, and Glory in the Age of the Hunnic Wars. 50 years that changed India.Amsterdam: J. Gonda Fund Foundation of the KNAW. pp. 484–534.ISBN978-9069847153.

- ^Schwartzberg, Joseph E.(1978).A Historical atlas of South Asia.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 25.ISBN0226742210.

- ^Schwartzberg, Joseph E.(1978).A Historical atlas of South Asia.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145, map XIV.1 (k).ISBN0226742210.

- ^Longman History & Civics ICSE 9 by Singhp. 81

- ^The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eralypp. 48 sq

- ^Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Senp. 221

- ^A Comprehensive History Of Ancient Indiap. 174

- ^abMeri 2006: 224

- ^Holl 2003: 9

- ^Kulke 2004: 106

- ^Luttwak 2009:167–68

- ^The Encyclopedia Americana 1989: 176

References

[edit]- An, Jiayao (2002). "When Glass Was Treasured in China". In Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (ed.).Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road.Brepols Publishers. pp. 79–94.ISBN2-503-52178-9.

- Ball, Warwick (2016).Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire(2nd ed.). Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-72078-6.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond; el al. (1984).Cross-Cultural Trade in World History.Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-26931-8.

- The Encyclopedia Americana(1989).Grolier. 1989.ISBN0-7172-0120-1.

- Farrokh, Kaveh(2007).Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War.Osprey Publishing.ISBN978-1-84603-108-3.

- Fayle, Charles Ernest (2006).A Short History of the World's Shipping Industry.Routledge.ISBN0-415-28619-0.

- Freeman, Donald B. (2003).The Straits of Malacca: Gateway Or Gauntlet?.McGill-Queen's Press.ISBN0-7735-2515-7.

- Harper, P.O. (2002). "Iranian Luxury Vessels in China From the Late First Millennium B.C.E. to the Second Half of the First Millennium C.E.". In Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (ed.).Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road.Brepols Publishers. pp. 95–113.ISBN2-503-52178-9.

- Hill, John E. (2009).Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE.BookSurge.ISBN978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (2003).Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements.Le xing ton Books.ISBN0-7391-0407-1.

- Huntingford, G.W.B. (1980).The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.Hakluyt Society.

- Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (2004).A History of India.Routledge.ISBN0-415-32919-1.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994).Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery. Book 1.University of Chicago Press.ISBN0-226-46731-7.

- Lieu, Samuel N.C. (2009). "Epigraphica Nestoriana Serica".Exegisti monumenta Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams.Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 227–46.ISBN978-3-447-05937-4.

- Lindsay, W S (2006).History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce.Adamant Media Corporation.ISBN0-543-94253-8.

- Luttwak, Edward (2009).The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire.Harvard University Press.ISBN978-0-674-03519-5.

- Mawer, Granville Allen (2013). "The Riddle of Cattigara". In Nichols, Robert and Martin Woods (ed.).Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia.National Library of Australia. pp. 38–39.ISBN9780642278098.

- Meri, Josef W.;Jere L. Bacharach (2006).Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia.Routledge.ISBN0-415-96690-6.

- O'Leary, De Lacy(2001).Arabia Before Muhammad.Routledge.ISBN0-415-23188-4.

- O'Reilly, Dougald J.W. (2007).Early Civilizations of Southeast Asia.AltaMira Press, Division of Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.ISBN978-0-7591-0279-8.

- Parker, Grant (2008).The Making of Roman India.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-85834-2.

- Potter, David Stone (2004).The Roman Empire at Bay: Ad 180–395.Routledge.ISBN0-415-10058-5.

- Schoff, Williamm H. (2004) [1912]. Lance Jenott (ed.).""The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century" in The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea ".Depts.washington.edu.University of Washington.Retrieved19 September2016.

- Shaw, Ian(2003).The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-280458-8.

- Suresh, S. (2004).SYMBOLS OF TRADE Roman and Pseudo-Roman Objects found in India(PDF).Manohar.

- Young, Gary Keith (2001).Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC–AD 305.Routledge.ISBN0-415-24219-3.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier (ed.).Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route.Vol. 1. Hakluyt Society.

Further reading

[edit]- Lionel Casson,The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text With Introduction, Translation, and Commentary.Princeton University Press,1989.ISBN0-691-04060-5.

- Chakrabarti D.K. (1990). The External Trade of the Indus Civilization. Delhi: Manoharlal Publishers Private Limited

- Chami, F. A. 1999. “The Early Iron Age on Mafia island and its relationship with the mainland.”AzaniaVol. XXXIV.

- McLaughlin, Raoul. (2010).Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China.Continuum, London and New York.ISBN978-1-84725-235-7.

- Miller, J. Innes. 1969.The Spice Trade of The Roman Empire: 29 B.C. to A.D. 641.Oxford University Press. Special edition for Sandpiper Books. 1998.ISBN0-19-814264-1.

- Sidebotham, Steven E. (2011).Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route.University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-24430-6.

- William Dalrymple,The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World.Bloomsbury Publishing,2024.

- Van der Veen, Marijke (2011).Consumption, Trade and Innovation. Exploring the Botanical Remains from the Roman and Islamic Ports at Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt.Frankfurt: Africa Magna Verlag.ISBN978-3-937248-23-3

- Raith, M. – Hoffbauer, R. – Euler, H. – Yule, P. – Damgaard, K. (2013). “The view from Ẓafār –An archaeometric study of the Aqaba late Roman period pottery complex and distribution in the 1st millennium CE”.Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie6, 320–50.ISBN978-3-11-019704-4.