Institute of Contemporary Arts

| |

| |

| Established | 1946 |

|---|---|

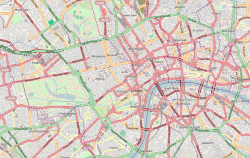

| Location | The Mall,London (offices inCarlton House Terrace) |

| Coordinates | 51°30′24″N0°07′50″W/ 51.506608°N 0.13061°W |

| Director | Bengi Unsal |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

TheInstitute of Contemporary Arts(ICA) is anartisticand cultural centre onThe MallinLondon,just offTrafalgar Square.Located within Nash House, part ofCarlton House Terrace,near theDuke of York StepsandAdmiralty Arch,the ICA contains galleries, a theatre, two cinemas, a bookshop and a bar.

History

[edit]The ICA was founded byRoland Penrose,Peter Watson,Herbert Read,Peter Gregory,[1]Geoffrey GrigsonandE. L. T. Mesensin 1946.[2]The ICA's founders intended to establish a space where artists, writers and scientists could debate ideas outside the traditional confines of theRoyal Academy.The model for establishing the ICA was the earlierLeeds Arts Club,founded in 1903 byAlfred Orage,of which Herbert Read had been a leading member. Like the ICA, this too was a centre for multi-disciplinary debate, combined with avant-garde art exhibition and performances, within a framework that emphasised a radical social outlook.[3]

The first two exhibitions at the ICA,40 Years of Modern Artand40,000 Years of Modern Art,were organised by Penrose, and reflected his interests inCubismandAfrican art,taking place in thebasement of the Academy Cinema,165 Oxford Street. The Academy Cinema building included the Pavilion, a restaurant, and the Marquee ballroom in the basement; the building was managed byGeorge Hoellering,the film, jazz and big band promoter.[4]In 1968Jasia Reichardtcurated the exhibition on computer generated art and music:Cybernetic Serendipityat the ICA.

With the acquisition of 17Dover Street,Piccadilly, in May 1950, the ICA was able to expand considerably. Ewan Phillips served as the first director. It was the former residence of Vice AdmiralHoratio Nelson.The gallery, clubroom and offices were refurbished by modernist architectJane Drewassisted by Neil Morris andEduardo Paolozzi.Paolozzi decorated the bar area and designed a metal and concrete table with studentTerence Conran.[5]

Ewan Phillips left in 1951, and Dorothy Morland was asked to take over temporarily, but stayed there as director for 18 years, until the move to the more spacious Nash House.[6] The criticReyner Banhamacted as assistant Director during the early 1950s, followed byLawrence Allowayduring the mid- to later 1950s. In its early years, the Institute organised exhibitions of modern art includingPicassoandJackson Pollock.AGeorges Braqueexhibition was held at the ICA in 1954. The first woman to exhibit there wasFahrelnissa Zeidin 1956. It also launchedPop art,Op art,and BritishBrutalistart and architecture. TheIndependent Groupmet at the ICA in 1952–1962/63 and organised several exhibitions, includingThis Is Tomorrow.

With the support of theArts Council,the ICA moved to its current site at Nash House in 1968, the refurbishment again designed byJane Drew.[7]For a period during the 1970s the institute was known for its often anarchic programme and administration.Norman Rosenthal,then director of exhibitions, was once assaulted by a group of people who were living in the upper floors of the building: a bloodstain on the wall of the administrative offices is preserved under glass, with a note reading "this is Normans's blood". Rosenthal claims the group which assaulted him included the actorKeith Allen.[8]

Bill McAllister was ICA Director from 1977 to 1990, when the Institute developed a system of separate departments specializing in visual art; cinema; and theatre, music and performance art. A fourth department was devoted to talks and lectures.Iwona Blazwickwas Director of Exhibitions from 1986 to 1993. Other notable curatorial and programming staff have includedLisa Appignanesi(deputy director of ICA and Head of Talks, 1980–90),James Lingwood(Exhibition Curator, 1986–90),Michael Morris(Director of Theatre),Lois Keidan,(Director of Live Arts, 1992–97),Catherine Ugwu,MBE (deputy director of Live Arts, 1991–97), Tim Highsted (deputy director of Cinema, 1988–95) andJens Hoffmann(Director of Exhibitions, 2003–07).

Mik Flood took over as director of the ICA in 1990 after McAllister's resignation. Flood announced that the Institute would have to leave its Mall location and move to a larger site, a plan that ultimately came to nothing.[9]He also oversaw a sponsorship scheme whereby the electrical goods companyToshibapaid to have their logo included on every piece of ICA publicity for three years, and in effect changed the name of the ICA to ICA/Toshiba.[10]He was replaced as Director in 1997 byPhilip Dodd.In 2002, the then ICA ChairmanIvan Massowcriticised what he described as "concept art", leading to his resignation.[11]

From 2003 to 2009, the ICA hostedComica,the London International Comics Festival, usually during periods when the ICA had no other events or exhibitions scheduled.[12]

Following the departure of Dodd, the ICA appointedEkow Eshunas artistic director in 2005.[13]Under Eshun's directorship the Live Arts Department was closed down in 2008, the charge for admission for non-members was abandoned (resulting in a reduction of membership numbers and a cash shortfall), the Talks Department lost all its personnel, and many commentators argued that the Institute suffered from a lack of direction.[14]A large financial deficit led to redundancies and resignations of key staff. Art critic JJ Charlesworth saw Eshun’s directorship as a direct cause of the ICA's ills; criticizing Eshun's reliance on private sponsorship, his cultivation of a "cool" ICA brand, and his focus on a cross-disciplinary approach that was put in place "at the cost", Charlesworth wrote "of a loss of curatorial expertise."[15]Problems between staff and Eshun, sometimes supported by the Chairman of the ICA Board,Alan Yentob,led to fractious and difficult staff relations.[16]Eshun resigned in August 2010, and Yentob announced he would leave.[17][18]

In January 2011, the ICA appointed as its Executive DirectorGregor Muir,who took up his post on 7 February 2011.[19]Muir stepped down in 2016 and was replaced by formerArtists SpacedirectorStefan Kalmár.[20]Kalmár was the first non-British Director of the ICA and made the cinemas fully independent. He announced his departure from the role after five years in August 2021 saying 'the moment now feels right for me to hand over to the next generation,' but also citing concerns around the loss of the 'arm's length principle' in UK arts funding and increasing Right-Wing attacks in the UK post-Brexit.[21]The ICA was hit hard by closures due to the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns from mid-March 2020 and reopened in July 2021 withWar Inna Babylon: the Community’s Struggle for Truths and Rights,an exhibition focused on the “various forms of state violence and institutional racism targeted at Britain’s Black communities."[22]In 2024, a group of former ICA workers alleged that the ICA fired them for their Palestinian advocacy. In response, artist Rheim Alkadhi, whose exhibition runs from June to September 2024, said she will pull her work out of London’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) if the organisation does not take accountability for retaliating against workers who have expressed solidarity with Palestinians.[23]

From 2012 to 2020 the gallery was refurbished byDavid Kohn Architects,a process that revealed some of the 1968 works by Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, practicing as Fry Drew and Partners.[24]

Notable exhibitions, talks, film festivals and music events

[edit]- 1948:40 Years of Modern Art,the ICA's first exhibition organised byHerbert ReadandRoland Penrose(10 February to 8 March, at Academy Hall, Oxford Street, W1).

- 1948:40,000 Years of Modern Art,the ICA's second exhibition organised by Herbert Read and Roland Penrose.

- 1948: The ICA and Mars Group organise a symposium on architecture.

- 1950:London-Paris: New Trends in Painting and Sculpturelaunched theGeometry of Fearsculptors.

- 1950:James Joyce:His Life and Work,first show in Dover Street at the ICA.

- 1951:Growth and Form,organised byRichard Hamilton.

- 1951: First ICA film screenings at the French Institute.

- 1952Sixteen Young Sculptors,organised byDavid Sylvester.

- 1952: Formation of theYoung Group,consisting of artists Nigel Henderson,Toni del Renzio,Reyner Banhamand Richard Lannoy, facilitated by the ICA Director Dorothy Morland.

- 1953:Herbert Readdelivers four lectures under the title "The Aesthetics of Sculpture".

- 1953:Alfred Barr,Director ofNew York City'sMuseum of Modern Art(MoMA) delivers a lecture entitled "They hate Modern Art or Patterns of Philistine Power".

- 1953: TheIndependent Group,including the sculptorEduardo Paolozzi,begins meeting at the ICA. This leads ultimately to the launch ofBritish Pop Art.The leading theorist of the group,Lawrence Alloway,lectures on "The Human Head in Modern Art".

- 1953:Pierre SchaefferperformsMusique Concrète.

- 1953:Parallel of Life and Art,organised byNigel Henderson,Eduardo PaolozziandAlison and Peter Smithson.

- 1953:Jackson Pollockfeatures in a show calledOpposing Forces.

- 1954:Man Raygives a talk on 'Painting of the Future and the Future of Painting'.

- 1955: UK Premiere ofKenneth Angerfilms.

- 1955: Public discussion on the works ofFrancis BaconwithLawrence AllowayandVictor Willing.

- 1955:Man, Machine and Motion,curated byRichard Hamilton.

- 1956:Richard Wollheimdelivers a lecture entitled "Art and Theory".

- 1956:Meyer Shapirodelivers a lecture entitled "Recent Abstract Painting in America".

- 1956:Ernst Gombrichdelivers a lecture entitled "Aspects of Communication through Painting".

- 1956:Reyner Banhamgives a talk on Revaluation and Futurism.

- 1956:Richard Hamilton,Anthony HillandColin St. John Wilsonin public discussion "Revaluation of Duchamp", the first revaluation ofMarcel Duchampin Britain after the Second World War.

- 1957: First UK screening of the French filmHurlements en Faveur de SadebyGuy Debord,which caused riots when shown in Paris because it mostly featured a black screen and silence.

- 1957:Paintings by Chimpanzees,curated by future ICA directorDesmond Morris.

- 1958:British Caribbean Writerstalk byStuart HallandV.S Naipaul.

- 1966–68:Yoko Onocontributes toDestruction in Art Symposiumorchestrated byGustav Metzger.

- 1967:Ian Dury,Pat Douthwaite,Herbert Kitchen andStass ParaskosexhibitionFantasy and Figuration.Dury was to become a celebrated punk rock musician, and Stass Paraskos had, in 1966, been the last artist in Britain to be successfully prosecuted for showing obscene paintings under theVagrancy Act 1838.

- 1968: The inaugural exhibition in the Nash buildingThe Obsessive Imagefeatures a waxwork model of a dead hippie byPaul Thek.TheCybernetic Serendipityexhibition features computers, pulsing TV screens and a mosaic floor made of coloured lights.

- 1976:Mary Kellyexhibits the first part ofPost-Partum Document,an exploration (developed between 1973 and 1979) of the mother-child relationship. Each section highlights a formative moment in her son’s mastery of language, along with the artist's sense of loss. Informed by feminism and psychoanalysis, the work alternately adopts the voice of the mother, the child, and an analytic observer. The installation provoked tabloid newspaper outrage because of stained (but laundered) nappy liners incorporated in "Documentation I".[25]

- 1976: A retrospective ofCOUM Transmissions(a performance group whose core subsequently formedThrobbing Gristle) entitledProstitutionfeatures sanitary towels and explicit photographs. The exhibition was held concurrently withMary Kelly'sPost-Partum Document.

- 1977:Adam and the Ants,at this point known simply as The Ants, perform their official debut concert in the restaurant. SingerAdam Ant's stage costume at this point includes abondage hoodand other leather garments. The performance is aborted by venue staff after one song, "Beat My Guest" (later the B-side of major hit single "Stand and Deliver"), but is resumed and completed later that day in the main theatre during the interval of a performance byJohn DowieandVictoria Wood.

- 1980: Sees several important feminist art exhibitions:

- 4–26 October,Women's Images of Men(curated by Joyce Agee, Jacqueline Morreau,Catherine Elwes,Pat Whiteread);[26]

- 30 October–9 November:About Time: Video, Performance and Installation by 21 Women Artists(curated byCatherine Elwes,Rose Garrard,Sandy Nairne);[27]

- 14 November–21 December:Issue: Social Strategies by Women Artists(curated byLucy R. Lippard).[28]

- 1981:Roger Westmanexhibited his schemeWalls: A Framework for Communal Anarchy.[29]

- 1986:Helen Chadwick’s artworkCarcass,consisting of composting vegetation in a perspex tower, is removed after the gasses from the compost caused the tower to give way. The smell led to complaints from neighbours and a visit by health inspectors. The main part of the exhibition, 'The Oval Court' (a major installation of sculptural forms, photocopies of animals, vegetation and the artist's body) was bought by theVictoria and Albert Museumfor its permanent collection.

- 1988:Taking Liberties: AIDS and Cultural Politics,organised by Erica Carter andSimon Watney,tackles cultural and activist responses to theAIDScrisis. A book of the same name is published bySerpent's Tailin 1989.

- 1989:Gerhard Richtershows black-and-white oil paintings of theBaader-Meinhof ganginspired by contemporary newspaper and police photographs.

- 1990:Vaclav Havellaunches Censored Theatre, a programme of readings of suppressed plays. The first reading ofDeath and the Maidenby the young Chilean playwrightAriel Dorfmanis performed by actors includingJuliet Stevenson.Harold Pinter,in the audience, said the play "felt like it was a sequel to his own 1984 play One for the Road, which also revolved around a woman who had been raped and tortured".[30]

- 1991:Damien Hirst’sInternational Affairs,his first solo exhibition in a public gallery, features glass cases containing items such as a desk, cigarette packets and an ashtray.

- 1992: The conferencePreaching to the Perverted,organised withThe Spanner Trustasks: "Are fetishistic practices politically radical?"[31]

- 1993: The exhibitionBad Girls,curated byKate BushandEmma Dexter,celebrates a new spirit of playfulness, tactility and perverse humour in the work of six British and US women artists:Helen Chadwick,Dorothy Cross,Rachel Evans,Nicole Eisenman,Nan GoldinandSue Williams.

- 1994: A video camera is set up in the men’s toilets of the ICA, and real-time images of urinating visitors are relayed to a screen in the theatre in a piece by Rosa Sanchez.

- 1994: The world's first cybercafe is held in the ICA theatre.

- 1995:BearandFive Easy Pieces,films by future Turner Prize-winning artistSteve McQueen,are included in the exhibitionMirage: Enigmas of Race, Difference and Desire,curated byDavid A. Baileyand organised withInIVA.Other artists whose work is included areSonia Boyce,Eddie George and Trevor Mathison ofBlack Audio Film Collective,Renée Green,Lyle Ashton Harris,Isaac Julien,Marc Latamie,andGlenn Ligon.An accompanying symposium,Working with Fanon,debates the legacy ofFrantz Fanonwithin the context of art and visual representation. Speakers includeHomi K. Bhabha,Paul Gilroy,Stuart Hall,bell hooks,Isaac Julien,Kobena Mercer,Raoul Peck,Ntozake Shange,Françoise Versages, andLola Young.[32]

- 1996:Jake and Dinos ChapmandisplayTragic Anatomies,sculptures of children with genitalia in place of facial features, as part of their exhibitionChapman World.

- 1996: TheOnedotzerodigital film festival is hosted at the ICA for the first time.

- 1996:Incarcerated with Artaud and Genettraces the legacies of the avant-garde French writers in a weekend event with participants including the writer and musicianPatti Smith,writerTahar Ben Jelloun,film makerAlejandro Jodorowsky,and theatre directorPeter Sellars.

- 1997: Four female models, naked apart from high-heeled shoes, stand in mute silence in an upstairs gallery for a piece by Italian artistVanessa Beecroftas part of the showMade in Italy.

- 2000: The annual Beck’s Futures prize is set up to celebrate the work of emerging artists, and continues at the ICA until 2005.

- 2006: TheAlien Nationexhibition is presented withinIVA,exploring the complex relationship between science fiction, race and contemporary art. Among the featured artists areLaylah Ali,Hew LockeandYinka Shonibare.

- 2008: Over a six-month period, and as part of the ICA's 60th-birthday year, the exhibitionNought to Sixtypresents 60 emerging artists based in Britain and Ireland.

- 2010: The first major solo exhibition of cult figure, artist, musician and writerBilly Childishis presented at the ICA.

- 2011: The ICA hostsBruderskriegsoundsystem,a project from Edwin Burdis,Mark Leckey,Kieron Livingston andSteven Claydon.Pablo Bronstein's exhibitionSketches for Regency Livingtakes over the entire ICA building for the first time in its history.

- 2015: The ICA hostsfig-2,[33]a one-year series of week-long exhibitions curated byFatoş Üstekthat included the artists Laura Eldret,Charles Avery,Rebecca Birch,Annika Ström,Young In Hong,Beth Collar,Tom McCarthy,Shezad Dawood,Suzanne Treister,Jacopo Miliani, Kathryn Elkin, Marjolijn Dijkman,Ben Judd,Karen Mirza,Oreet Ashery,Eva Grubinger,Melanie Manchot,Bruce McLean,Vesna Petresin, and duo Wright and Vandame.

- 2016: The first edition of FRAMES of REPRESENTATION (FoR) film festival was launched on the 20th of April 2016. FoR was conceived to engage with new visions of cinema through the presentation of innovative and politically aware cinematic languages situated at the intersection between fiction and non-fiction. Throughout its ongoing annual event, the festival presented international and UK premieres of films byRoberto Minervini,Khalik Allah,Salome' Lamas,Wang Bing,Clement Cogitore,Teddy Williams,Nele Wohlatz, Betzabe' Garcia, Anna Zamecka, Gürcan Keltek,Pietro Marcello,Zhao Liang,Yalda Afsah,Rosa Barba,Ana Vaz, Isabel Pagliai, Dorian Jespers, Alexander Abaturov, Zhu Shengze to mention a few; masterclasses, workshops and conversations with speaker guests such asWalter Murch,Gianfranco Rosi,Laura Poitras,Joshua OppenheimerandCarlos Reygadasamongst many others. The fifth edition of the festival originally planned for April 2020 was postponed due to theCOVID-19 pandemicbut due to taking place at the end of 2020.[34]

- 2019: Image Behaviour with works fromNora Turato,Marianna Simnett,Hannah Quinlan + Rosie Hastings, Keiken,Lawrence Lek+ Clifford Sage, Andros Zins-Browne, Lexachast (Amnesia Scanner,Bill Kouligas,Harm van den Dorpel), Ken Okiishi, Julie Béna,Patrick Staff,and others.[35]

- 2019:I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker,the first UK exhibition dedicated to the American writerKathy Acker(1947 – 1997), and her written, spoken and performed work. With works and contributions by:Reza Abdoh,Carl Gent, Leslie Asako Gladsjø, Bette Gordon,Penny Goring,Johanna Hedva, Caspar Heinemann, Every Ocean Hughes, Bhanu Kapil, Ghislaine Leung, Sophie Lewis, Candice Lin, Stephen Littman, Rosanna McNamara, Reba Maybury,The Mekons,D. Mortimer,Precious Okoyomon,Genesis P-Orridge,Raúl Ruiz,Sarah Schulman,Nancy Spero,David Wojnarowicz,and others.

- 2020: Since January 2020, INFERNO queer techno rave have held regular parties and events at the ICA, with DJs and performance commissions including byLewis G. Burton,Samantha Togni andSweatmother.

- In 2022 INFERNO commissioned Sweatmother to makeDyke, Just Do It,which was further developed into a full-length live performance debuting at the ICA in October 2023.

- In 2023, the installation of ad&b audiotechnikSoundscape system in the Theatre, and concerts byKing Krule,Bendik Giske,Okkyung Lee,and as part of theMinus Onelive performance series, 'Landscapes' by Tutto Questo Sentire including musiciansSandro Mussida,Olivia Salvadori,Kenichi Iwasa,Maxwell Sterling,Jan Hendrickse,Coby Sey,Akihide Monna, light artist Charlie Hope, and video artistRebecca Salvadori

- In 2024, concerts includingGoat Girl,Keeley Forsyth,Claire Rousay,andgoat jp.

Organisation

[edit]Membership of the ICA is available to the general public. The ICA is constituted as a private limited company and registered charity, run by a 13-member Board and led by a Director.

ICA Directors

[edit]- Ewan Phillips 1948–1951

- Dorothy Morland1951–1967

- Desmond Morris1967–1968

- Michael Kustow 1968–1970

- Peter Cook1970–1973

- Ted Little 1973–1977

- Bill McAlister 1977–1990

- Mik Flood 1990–1997

- Philip Dodd1997–2004

- Ekow Eshun2005–2010

- Gregor Muir2011–2016

- Stefan Kalmar 2016–2021

- Bengi Unsal 2022–present.[36]

See also

[edit]- Artangel,founded by former Exhibition Curator James Lingwood and Director of Performance Michael Morris.

- Live Art Development Agency,founded by former Director of Live Arts Lois Keidan.

References

[edit]- ^Jane Drew toThe Times,14 February 1959.

- ^"About".ICA.Retrieved26 April2021.

- ^Nannette Aldred, 'A sufficient Flow of Vital Ideas: Herbert Read and the Flow of Ideas from the Leeds Arts Club to the ICA' in Michael Paraskos (ed.)Re-Reading Read: New Views on Herbert Read(London: Freedom Press, 2008) p. 70.

- ^Allen Eyles,"Cinemas & Cinemagoing: Art House & Repertory"Archived3 March 2016 at theWayback Machine,BFI Screenonline.

- ^Massey, A. (1995).The Independent Group: modernism and mass culture in Britain, 1945-59.Manchester (England): Manchester University Press.

- ^Sile Flower, Jean Macfarlane, Ruth Plant,Jane B. Drew, architect: A tribute from her colleagues and friends for her 75th birthday 24 March 1986,p. 23. Bristol: Bristol Centre for the Advancement of Architecture, 1986,ISBN0-9510759-0-X.

- ^"David Kohn Architects: Institute of Contemporary Arts".davidkohn.co.uk.Retrieved21 August2024.

- ^Hattenstone, Simon (25 November 2002)."I'm a lucky bugger".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2017.

- ^Nowicka, Helen; Welch, Jilly (12 August 1994)."ICA to quit Mall for big river complex".The Independent.London.Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2017.

- ^Chin-Tao Wu (2003).Privatising culture: corporate art intervention since the 1980s.Verso. p. 145.

- ^Gibbons, Fiachra (17 January 2002)."Concept art is pretentious tat, says ICA chief".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2017.

- ^Freeman, John(30 October 2009)."Matters of Convention: ComICA".DownTheTubes.net.

- ^Alberge, Dalya (10 March 2005)."ICA appoints the first black gallery director".The Times.London.[dead link]

- ^"Should we let the ICA die".The Times.London. 28 January 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 15 June 2011.

- ^Milliard, Coline."London ICA Director Ekow Eshun Submits His Resignation | BLOUIN ARTINFO".Artinfo.Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2013.Retrieved18 April2014.

- ^Higgins, Charlotte (23 January 2010)."ICA warns staff it could close by May".The Guardian.London.

- ^Edemariam, Aida (27 August 2010)."Ekow Eshun and Alan Yentob to quit after ICA survives crisis".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2015.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^Edemariam, Aida (28 August 2010)."Ekow Eshun: 'It's been a tough year...'".The Guardian.London.

- ^Brown, Mark (11 January 2011)."Gregor Muir to be new ICA chief".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2015.

- ^Brown, Mark (19 September 2016)."Stefan Kalmár appointed as new director of the ICA".The Guardian.London.Archivedfrom the original on 18 March 2017.In March 2022, the ICA appointed its recent Director Bengi Unsal, previously the Head of Contemporary Music at Southbank Centre.

- ^Article, Sarah Cascone ShareShare This (10 August 2021)."ICA London Director Stefan Kalmár on How British Politics—and Right-Wing Attacks—Sparked His Departure From the Museum".Artnet News.Retrieved30 April2024.

- ^"Stefan Kalmár steps down as director of ICA London after five years".The Art Newspaper - International art news and events.10 August 2021.Retrieved30 April2024.

- ^"London Art Institute Workers Say They Were Fired for Supporting Palestine".19 July 2024.

- ^"David Kohn Architects: Institute of Contemporary Arts".davidkohn.co.uk.Retrieved21 August2024.

- ^Kelly, Mary."Post-Partum Document".Mary Kelly.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2013.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^Nairne, Sandy (1908).Women's Images of Men.London: ICA.ISBN0-905263-07-3.

- ^Elwes, Catherine (1980).About Time: Video, Performance and Installation by 21 Women Artists.London: ICA.ISBN0-905263-08-1.

- ^Lippard, Lucy (1980).Issue: Social Strategies by Women Artists.London: ICA.ISBN0-905263-09-X.

- ^Hardy, Dennis (2004).Arcadia for All: The Legacy of a Makeshift Landscape.Five Leaves. pp. 301 and 304.ISBN0907123597.

- ^Shenton, Mark."Death and the Maiden".The Stage.Retrieved2 February2014.

- ^"Are Fetishistic Practices Politically Radical".British Library Sound Archive.Archivedfrom the original on 19 February 2014.Retrieved1 February2014.

- ^Haye, Christian."Just an Illusion".frieze. Archived fromthe originalon 23 February 2014.Retrieved12 February2014.

- ^"fig-futures".fig-futures.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2018.Retrieved7 May2018.

- ^"ICA | FRAMES of REPRESENTATION 2020".ica.art.

- ^"ICA | Image Behaviour".Archived fromthe originalon 2 March 2020.

- ^Solomon, Tessa (10 August 2021)."ICA London Director to Step Down, Citing Need to 'Hand Over to the Next Generation'".ARTNews.

External links

[edit]- 1947 establishments in England

- Art museums and galleries established in 1947

- Art museums and galleries in London

- Arts centres in London

- Buildings and structures on The Mall, London

- Cinemas in London

- Contemporary art galleries in London

- Museums in the City of Westminster

- Performing arts in London

- Theatres in the City of Westminster

- Tourist attractions in the City of Westminster