Isentropic process

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

Anisentropic processis an idealizedthermodynamic processthat is bothadiabaticandreversible.[1][2][3][4][5][6][excessive citations]Theworktransfers of the system arefrictionless,and there is no net transfer ofheatormatter.Such an idealized process is useful in engineering as a model of and basis of comparison for real processes.[7]This process is idealized because reversible processes do not occur in reality; thinking of a process as both adiabatic and reversible would show that the initial and final entropies are the same, thus, the reason it is called isentropic (entropy does not change).Thermodynamicprocesses are named based on the effect they would have on the system (ex. isovolumetric: constant volume, isenthalpic: constant enthalpy). Even though in reality it is not necessarily possible to carry out an isentropic process, some may be approximated as such.

The word "isentropic" derives from the process being one in which theentropyof the system remains unchanged. In addition to a process which is both adiabatic and reversible, this can also occur in a system where the work done on the system includesfrictioninternal to the system, and heat is withdrawn from the system sufficient to compensate for it so as to leave the entropy unchanged.[8]However, in relation to theUniverse,its entropy would increase as a result, in agreement with theSecond Law of Thermodynamics.[citation needed]

Background[edit]

Thesecond law of thermodynamicsstates[9][10]that

whereis the amount of energy the system gains by heating,is thetemperatureof the surroundings, andis the change in entropy. The equal sign refers to areversible process,which is an imagined idealized theoretical limit, never actually occurring in physical reality, with essentially equal temperatures of system and surroundings.[11][12]For an isentropic process, if also reversible, there is no transfer of energy as heat because the process isadiabatic;δQ= 0. In contrast, if the process is irreversible, entropy is produced within the system; consequently, in order to maintain constant entropy within the system, energy must be simultaneously removed from the system as heat.

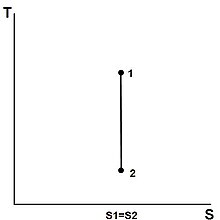

For reversible processes, an isentropic transformation is carried out by thermally "insulating" the system from its surroundings. Temperature is the thermodynamicconjugate variableto entropy, thus the conjugate process would be anisothermal process,in which the system is thermally "connected" to a constant-temperature heat bath.

Isentropic processes in thermodynamic systems[edit]

The entropy of a given mass does not change during a process that is internally reversible and adiabatic. A process during which the entropy remains constant is called an isentropic process, writtenor.[13]Some examples of theoretically isentropic thermodynamic devices arepumps,gas compressors,turbines,nozzles,anddiffusers.

Isentropic efficiencies of steady-flow devices in thermodynamic systems[edit]

Most steady-flow devices operate under adiabatic conditions, and the ideal process for these devices is the isentropic process. The parameter that describes how efficiently a device approximates a corresponding isentropic device is called isentropic or adiabatic efficiency.[13]

Isentropic efficiency of turbines:

Isentropic efficiency of compressors:

Isentropic efficiency of nozzles:

For all the above equations:

- is the specificenthalpyat the entrance state,

- is the specific enthalpy at the exit state for the actual process,

- is the specific enthalpy at the exit state for the isentropic process.

Isentropic devices in thermodynamic cycles[edit]

| Cycle | Isentropic step | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IdealRankine cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression in apump |

| IdealRankine cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion in aturbine |

| IdealCarnot cycle | 2→3 | Isentropic expansion |

| IdealCarnot cycle | 4→1 | Isentropic compression |

| IdealOtto cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression |

| IdealOtto cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion |

| IdealDiesel cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression |

| IdealDiesel cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion |

| IdealBrayton cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression in acompressor |

| IdealBrayton cycle | 3→4 | Isentropic expansion in aturbine |

| Idealvapor-compression refrigerationcycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression in acompressor |

| IdealLenoir cycle | 2→3 | Isentropic expansion |

| IdealSeiliger cycle | 1→2 | Isentropic compression |

| IdealSeiliger cycle | 4→5 | Isentropic compression |

Note: The isentropic assumptions are only applicable with ideal cycles. Real cycles have inherent losses due to compressor and turbine inefficiencies and the second law of thermodynamics. Real systems are not truly isentropic, but isentropic behavior is an adequate approximation for many calculation purposes.

Isentropic flow[edit]

Influid dynamics,anisentropic flowis afluid flowthat is both adiabatic and reversible. That is, no heat is added to the flow, and no energy transformations occur due tofrictionordissipative effects.For an isentropic flow of aperfect gas,several relations can be derived to define the pressure, density and temperature along a streamline.

Note that energycanbe exchanged with the flow in an isentropic transformation, as long as it doesn't happen as heat exchange. An example of such an exchange would be an isentropic expansion or compression that entails work done on or by the flow.

For an isentropic flow, entropy density can vary between different streamlines. If the entropy density is the same everywhere, then the flow is said to behomentropic.

Derivation of the isentropic relations[edit]

For a closed system, the total change in energy of a system is the sum of the work done and the heat added:

The reversible work done on a system by changing the volume is

whereis thepressure,andis thevolume.The change inenthalpy() is given by

Then for a process that is both reversible and adiabatic (i.e. no heat transfer occurs),,and soAll reversible adiabatic processes are isentropic. This leads to two important observations:

Next, a great deal can be computed for isentropic processes of an ideal gas. For any transformation of an ideal gas, it is always true that

- ,and

Using the general results derived above forand,then

So for an ideal gas, theheat capacity ratiocan be written as

For a calorically perfect gasis constant. Hence on integrating the above equation, assuming a calorically perfect gas, we get

that is,

Using theequation of statefor an ideal gas,,

(Proof:ButnR= constant itself, so.)

also, for constant(per mole),

- and

Thus for isentropic processes with an ideal gas,

- or

Table of isentropic relations for an ideal gas[edit]

Derived from

where:

- = pressure,

- = volume,

- = ratio of specific heats =,

- = temperature,

- = mass,

- = gas constant for the specific gas =,

- = universal gas constant,

- = molecular weight of the specific gas,

- = density,

- = specific heat at constant pressure,

- = specific heat at constant volume.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Partington, J. R.(1949),An Advanced Treatise on Physical Chemistry.,vol. 1, Fundamental Principles. The Properties of Gases, London:Longmans, Green and Co.,p. 122.

- ^Kestin, J. (1966).A Course in Thermodynamics,Blaisdell Publishing Company, Waltham MA, p. 196.

- ^Münster, A. (1970).Classical Thermodynamics,translated by E. S. Halberstadt, Wiley–Interscience, London,ISBN0-471-62430-6,p. 13.

- ^Haase, R. (1971). Survey of Fundamental Laws, chapter 1 ofThermodynamics,pages 1–97 of volume 1, ed. W. Jost, ofPhysical Chemistry. An Advanced Treatise,ed. H. Eyring, D. Henderson, W. Jost, Academic Press, New York, lcn 73–117081, p. 71.

- ^Borgnakke, C., Sonntag., R.E. (2009).Fundamentals of Thermodynamics,seventh edition, Wiley,ISBN978-0-470-04192-5,p. 310.

- ^Massey, B. S. (1970),Mechanics of Fluids,Section 12.2 (2nd edition) Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, London. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-25005, p. 19.

- ^Çengel, Y. A., Boles, M. A. (2015).Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach,8th edition, McGraw-Hill, New York,ISBN978-0-07-339817-4,p. 340.

- ^Çengel, Y. A., Boles, M. A. (2015).Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach,8th edition, McGraw-Hill, New York,ISBN978-0-07-339817-4,pp. 340–341.

- ^Mortimer, R. G.Physical Chemistry,3rd ed., p. 120, Academic Press, 2008.

- ^Fermi, E.Thermodynamics,footnote on p. 48, Dover Publications,1956 (still in print).

- ^Guggenheim, E. A.(1985).Thermodynamics. An Advanced Treatment for Chemists and Physicists,seventh edition, North Holland, Amsterdam,ISBN0444869514,p. 12: "As a limiting case between natural and unnatural processes[,] we have reversible processes, which consist of the passage in either direction through a continuous series of equilibrium states. Reversible processes do not actually occur..."

- ^Kestin, J. (1966).A Course in Thermodynamics,Blaisdell Publishing Company, Waltham MA, p. 127: "However, by a stretch of imagination, it was accepted that a process, compression or expansion, as desired, could be performed 'infinitely slowly'[,] or as is sometimes said,quasistatically."P. 130:" It is clear thatall natural processes are irreversibleand that reversible processes constitute convenient idealizations only. "

- ^abCengel, Yunus A., and Michaeul A. Boles. Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach. 7th Edition ed. New York: Mcgraw-Hill, 2012. Print.

References[edit]

- Van Wylen, G. J. and Sonntag, R. E. (1965),Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics,John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19470