Jacques Amyot

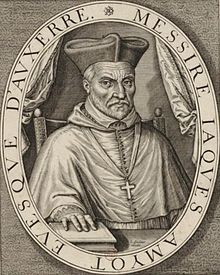

Portrait byLéonard Gaultier.

Jacques Amyot(French:[amjo];30 October 1513 – 6 February 1593),French Renaissancebishop, scholar, writer andtranslator,was born of poor parents, atMelun.

Biography[edit]

Amyot found his way to theUniversity of Paris,where he supported himself by serving some of the richer students. He was nineteen when he becameM.A.at Paris, and later he graduated doctor ofcivil lawatBourges.Through Jacques Colure (or Colin),abbotof St. Ambrose in Bourges, he obtained a tutorship in the family of a secretary of state. By the secretary he was recommended toMargaret of France, Duchess of Berry,and through her influence was made professor ofGreekandLatinat Bourges. Here he translated theÆthiopicaofHeliodorus(1547), for which he was rewarded byFrancis Iwith theabbeyof Bellozane.[1]

He was thus enabled to go to Italy to study theVaticantext ofPlutarch,on the translation of whoseLives(1559–1565) he had been some time engaged. On the way he turned aside on a mission to theCouncil of Trent.Returning home, he was appointed tutor to the sons ofHenry II,by one of whom (Charles IX) he was afterwards made grandalmoner(1561) and by the other (Henry III) was appointed, in spite of his plebeian origin, commander of theOrder of the Holy Spirit.[1]

Pius Vpromoted him to thebishopric of Auxerrein 1570,[2]and here he continued to live in comparative quiet, repairing his cathedral and perfecting his translations, for the rest of his days, though troubled towards the close by the insubordination and revolts of hisclergy.He was a devout and conscientious churchman, and had the courage to stand by his principles. It is said that he advised the chaplain of Henry III to refuseabsolutionto the king after the murder of theGuiseprinces. He was, nevertheless, suspected of approving the crime. His house was plundered, and he was compelled to leave Auxerre for some time. He died bequeathing, it is said, 1200 crowns to the hospital atOrléansfor the twelvedeniershe received there when "poor and naked" on his way to Paris.[1]

He translated seven books ofDiodorus Siculus(1554), theDaphnis and ChloëofLongus(1559) and theOpera MoraliaofPlutarch(1572). His vigorous and idiomatic version of Plutarch,Vies des hommes illustres,was translated into English bySir Thomas North,and suppliedShakespearewith materials for his Roman plays.Montaignesaid of him, "I give the palm to Jacques Amyot over all our French writers, not only for the simplicity and purity of his language in which he surpasses all others, nor for his constancy to so long an undertaking, nor for his profound learning... but I am grateful to him especially for his wisdom in choosing so valuable a work."[1]

It was indeed to Plutarch that Amyot devoted his attention. His other translations were subsidiary. The version of Diodorus he did not publish, although the manuscript had been discovered by him. Amyot took great pains to find and interpret correctly the best authorities, but the interest of his books today lies in the style. His translation reads like an original work. The personal method of Plutarch appealed to a generation addicted to memoirs and incapable of any general theory of history. Amyot's book, therefore, obtained an immense popularity, and exercised great influence over successive generations of French writers.[1]

References[edit]

- ^abcdeOne or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Amyot, Jacques".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 901.Endnotes:

- Edition of the works of Amyot from the firm ofDidot(25 vols, 1818–1821)

- Auguste de Blignières,Essai sur Amyot et les traducteurs français au xviesiècle(Paris, 1851)

- ^"Amyot, Jacques (1513-93)" inChambers's Encyclopaedia.London:George Newnes,1961, Vol. 1, p. 393.