James Hutton

James Hutton | |

|---|---|

Portrait byHenry Raeburn,1776 | |

| Born | 3 June 1726 Edinburgh,Scotland |

| Died | 26 March 1797 (aged 70) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geology |

| Notes | |

Member of theRoyal Society of Agriculture of France | |

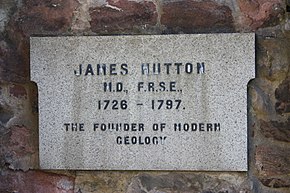

James HuttonFRSE(/ˈhʌtən/;3 JuneO.S.[1]1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottishgeologist,agriculturalist,chemical manufacturer,naturalistandphysician.[2]Often referred to as the "Father of Modern Geology,"[3][4]he played a key role in establishing geology as a modern science.

Hutton advanced the idea that the physical world'sremote historycan be inferred from evidence in present-day rocks. Through his study of features in the landscape and coastlines of his nativeScottish lowlands,such asSalisbury CragsorSiccar Point,he developed the theory that geological features could not be static but underwent continuing transformation over indefinitely long periods of time. From this he argued, in agreement with many other early geologists, that the Earth could not be young. He was one of the earliest proponents of what in the 1830s became known asuniformitarianism,the science which explains features of theEarth's crustas the outcome of continuing natural processes over the longgeologic time scale.Hutton also put forward a thesis for a 'system of the habitable Earth' proposed as adeisticmechanism designed to keep the world eternally suitable for humans,[5]an early attempt to formulate what today might be called one kind ofanthropic principle.

Some reflections similar to those of Hutton can be found in publications of his contemporaries, such as the French naturalistGeorges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon,[5]but it is chiefly Hutton's pioneering work that established the field.[6][7]

Early life and career

[edit]Hutton was born inEdinburghon 3 June O.S.[8]1726, as one of five children of Sarah Balfour and William Hutton, a merchant who was Edinburgh City Treasurer. Hutton's father died in 1729, when he was three.

He was educated at theHigh School of Edinburghwhere he was particularly interested inmathematicsandchemistry,then when he was 14 he attended theUniversity of Edinburghas a "student of humanity", studying theclassics.He was apprenticed to the lawyer George ChalmersWSwhen he was 17, but took more interest in chemical experiments than legal work. At the age of 18, he became a physician's assistant, and attended lectures in medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

After a two-year stay in Paris, James Hutton arrived in Leiden in 1749, where he enrolled at the University of Leiden on 14 August 1749, at the home of the then rector magnificus Joachim Schwartz to obtain a doctorate in medicine. He stayed with the widow Van der Tas (née Judith Bouvat) at the Langebrug, which corresponds to the current address Langebrug 101 in Leiden. His supervisor was Professor Frederik Winter, who was not only a professor at Leiden University, but also court physician to the Stadholder. The Latin manuscript of Hutton's dissertation also contained 92 theses, two of which were successfully defended in public by James Hutton on 3 September 1749. On 12 September 1749, James Hutton obtained his doctorate in medicine from Leiden University with a physico-medical thesis entitledSanguine et Circulatione Microcosmi.The thesis was printed by Wilhelmus Boot, book printer in Leiden. It is believed that James Hutton returned to Britain shortly after his promotion.[9][10]: 2

After his degree Hutton went to London, then in mid-1750 returned to Edinburgh and resumed chemical experiments with close friend, John Davie. Their work on production ofsal ammoniacfromsootled to their partnership in a profitable chemical works,[10]: 2 manufacturing the crystalline salt which was used for dyeing, metalworking and as smelling salts and had been available only from natural sources and had to be imported fromEgypt.Hutton owned and rented out properties in Edinburgh, employing a factor to manage this business.[11]

Farming and geology

[edit]Hutton inherited from his father theBerwickshirefarms ofSlighhouses,a lowland farm which had been in the family since 1713, and the hill farm ofNether Monynut.[10]: 2–3 In the early 1750s he moved toSlighhousesand set about making improvements, introducing farming practices from other parts of Britain and experimenting with plant and animal husbandry.[10]: 2–3 He recorded his ideas and innovations in an unpublished treatise onThe Elements of Agriculture.[10]: 60

This developed his interest inmeteorologyand geology. In a 1753 letter he wrote that he had "become very fond of studying the surface of the earth, and was looking with anxious curiosity into every pit or ditch or bed of a river that fell in his way". Clearing and draining his farm provided ample opportunities. The mathematicianJohn Playfairdescribed Hutton as having noticed that "a vast proportion of the present rocks are composed of materials afforded by the destruction of bodies, animal, vegetable and mineral, of more ancient formation". His theoretical ideas began to come together in 1760. While his farming activities continued, in 1764 he went on a geological tour of the north of Scotland with George Maxwell-Clerk,[12]ancestor of the famousJames Clerk Maxwell.[13]

Edinburgh and canal building

[edit]In 1768, Hutton returned to Edinburgh, letting his farms to tenants but continuing to take an interest in farm improvements and research which included experiments carried out atSlighhouses.He developed a red dye made from the roots of themadderplant.[14]

He had a house built in 1770 at St John's Hill, Edinburgh, overlookingSalisbury Crags.This later became the Balfour family home and, in 1840, the birthplace of the psychiatristJames Crichton-Browne.Hutton was one of the most influential participants in theScottish Enlightenment,and fell in with numerous first-class minds in the sciences including mathematicianJohn Playfair,philosopherDavid Humeand economistAdam Smith.[15]Hutton held no position in the University of Edinburgh and communicated his scientific findings through theRoyal Society of Edinburgh.He was particularly friendly with physician and chemistJoseph Black,and together with Adam Smith they founded theOyster Clubfor weekly meetings.

Between 1767 and 1774 Hutton had close involvement with the construction of theForth and Clyde canal,making full use of his geological knowledge, both as a shareholder and as a member of the committee of management, and attended meetings including extended site inspections of all the works. At this time he is listed as living on Bernard Street inLeith.[16]In 1777 he published a pamphlet onConsiderations on the Nature, Quality and Distinctions of Coal and Culmwhich successfully helped to obtain relief from excise duty on carrying small coal.[17]

In 1783, he was a joint founder of theRoyal Society of Edinburgh.[18]

Later life and death

[edit]

From 1791 Hutton suffered extreme pain fromstones in the bladderand gave up field work to concentrate on finishing his books. A dangerous and painful operation failed to resolve his illness.[19]He died in Edinburgh and was buried in the vault of Andrew Balfour, opposite the vault of his friendJoseph Black,in the now sealed south-west section ofGreyfriars Kirkyardin Edinburgh, commonly known as the Covenanter's Prison.

Hutton did not marry and had no legitimate children.[18]Around 1747, he had a son by a Miss Edington, and though he gave his child, James Smeaton Hutton, financial assistance, he had little to do with the boy, who went on to become a post-office clerk in London.[20]

Theory of rock formations

[edit]Hutton developed several hypotheses to explain therock formationshe saw around him, but according to Playfair he "was in no haste to publish his theory; for he was one of those who are much more delighted with the contemplation of truth, than with the praise of having discovered it". After some 25 years of work,[21]hisTheory of the Earth;or an Investigation of the Laws observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globewas read to meetings of theRoyal Society of Edinburghin two parts, the first by his friendJoseph Blackon 7 March 1785, and the second by himself on 4 April 1785. Hutton subsequently read an abstract of his dissertationConcerning the System of the Earth, its Duration and Stabilityto Society meeting on 4 July 1785,[22]which he had printed and circulated privately.[23]In it, he outlined his theory as follows;

The solid parts of the present land appear in general, to have been composed of the productions of the sea, and of other materials similar to those now found upon the shores. Hence we find reason to conclude:

1st, That the land on which we rest is not simple and original, but that it is a composition, and had been formed by the operation of second causes.

2nd, That before the present land was made, there had subsisted a world composed of sea and land, in which were tides and currents, with such operations at the bottom of the sea as now take place. And,Lastly, That while the present land was forming at the bottom of the ocean, the former land maintained plants and animals; at least the sea was then inhabited by animals, in a similar manner as it is at present.

Hence we are led to conclude, that the greater part of our land, if not the whole had been produced by operations natural to this globe; but that in order to make this land a permanent body, resisting the operations of the waters, two things had been required;

1st, The consolidation of masses formed by collections of loose or incoherent materials;

2ndly, The elevation of those consolidated masses from the bottom of the sea, the place where they were collected, to the stations in which they now remain above the level of the ocean.

Search for evidence

[edit]

In the summer of 1785 atGlen Tiltand other sites in theCairngorm mountainsin theScottish Highlands,Hutton foundgranitepenetratingmetamorphicschists,in a way which indicated that the granite had beenmoltenat the time. This was Hutton's first geological field trip and he was invited by the Duke of Atholl to his hunting lodge, Forest Lodge. The exposures at the Dail-an-eas Bridge demonstrated to him that granite formed from the cooling of molten rock rather than itprecipitatingout of water as others at the time believed, and therefore the granite must be younger than the schists.[24][25]Hutton presented his theory of the earth on 4 March and 7 April 1785, at the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[26]

He went on to find a similar penetration ofvolcanic rockthroughsedimentary rockinEdinburgh,atSalisbury Crags,[4]adjoiningArthur's Seat– this area of the Crags is now known as Hutton's Section.[27][28]He found other examples inGallowayin 1786, and on theIsle of Arranin 1787.

The existence ofangular unconformitieshad been noted byNicolas Stenoand by French geologists includingHorace-Bénédict de Saussure,who interpreted them in terms ofNeptunismas "primary formations". Hutton wanted to examine such formations himself to see "particular marks" of the relationship between the rock layers. On the 1787 trip to theIsle of Arranhe found his first example ofHutton's Unconformityto the north of Newton Point nearLochranza,[29][30]but the limited view meant that the condition of the underlying strata was not clear enough for him,[31]and he incorrectly thought that the strata were conformable at a depth below the exposed outcrop.[32]

Later in 1787 Hutton noted what is now known as the Hutton or "Great" Unconformity at Inchbonny,[6]Jedburgh,in layers ofsedimentary rock.[33]As shown in the illustrations to the right, layers ofgreywackein the lower layers of the cliff face are tilted almost vertically, and above an intervening layer ofconglomeratelie horizontal layers ofOld Red Sandstone.He later wrote of how he "rejoiced at my good fortune in stumbling upon an object so interesting in the natural history of the earth, and which I had been long looking for in vain." That year, he found the same sequence inTeviotdale.[31]

In the Spring of 1788 he set off withJohn Playfairto theBerwickshirecoast and found more examples of this sequence in the valleys of the Tour and Pease Burns nearCockburnspath.[31]They then took a boat trip from Dunglass Burn east along the coast with the geologistSir James HallofDunglass.They found the sequence in the cliff below St. Helens, then just to the east atSiccar Pointfound what Hutton called "a beautiful picture of this junction washed bare by the sea".[34][35]Playfair later commented about the experience, "the mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time".[36]Continuing along the coast, they made more discoveries including sections of the vertical beds showing strong ripple marks which gave Hutton "great satisfaction" as a confirmation of his supposition that these beds had been laid horizontally in water. He also found conglomerate at altitudes that demonstrated the extent of erosion of the strata, and said of this that "we never should have dreamed of meeting with what we now perceived".[31]

Hutton reasoned that there must have been innumerable cycles, each involvingdepositionon theseabed,uplift with tilting anderosionthen undersea again for further layers to be deposited. On the belief that this was due to the same geological forces operating in the past as the very slow geological forces seen operating at the present day, the thicknesses of exposed rock layers implied to him enormous stretches of time.[6]

Publication

[edit]Though Hutton circulated privately a printed version of the abstract of his Theory (Concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration, and Stability) which he read at a meeting of theRoyal Society of Edinburghon 4 July 1785;[23]the full account of his theory as read at 7 March 1785 and 4 April 1785 meetings did not appear in print until 1788. It was titledTheory of the Earth;or an Investigation of the Laws observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globeand appeared inTransactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,vol. I, Part II, pp. 209–304, plates I and II, published 1788.[22]He put forward the view that "from what has actually been, we have data for concluding with regard to that which is to happen thereafter." This restated theScottish Enlightenmentconcept whichDavid Humehad put in 1777 as "all inferences from experience suppose... that the future will resemble the past", andCharles Lyellmemorably rephrased in the 1830s as "the present is the key to the past".[37]Hutton's 1788 paper concludes; "The result, therefore, of our present enquiry is, that we find no vestige of a beginning,–no prospect of an end."[22]His memorably phrased closing statement has long been celebrated.[6][38](It was quoted in the 1989 song "No Control"by songwriter and professorGreg Graffin.[39])

Following criticism, especially the arguments fromRichard Kirwanwho thought Hutton's ideas wereatheisticand not logical,[22]Hutton published a two volume version of his theory in 1795,[40][41]consisting of the 1788 version of his theory (with slight additions) along with a lot of material drawn from shorter papers Hutton already had to hand on various subjects such as the origin of granite. It included a review of alternative theories, such as those ofThomas BurnetandGeorges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon.

The whole was entitledAn Investigation of the Principles of Knowledge and of the Progress of Reason, from Sense to Science and Philosophywhen the third volume was completed in 1794.[42]Its 2,138 pages prompted Playfair to remark that "The great size of the book, and the obscurity which may justly be objected to many parts of it, have probably prevented it from being received as it deserves."

Opposing theories

[edit]His new theories placed him into opposition with the then-popularNeptunisttheories of the German geologistAbraham Gottlob Werner,that all rocks had precipitated out of a single enormous flood. Hutton proposed that theinterior of the Earthwas hot, and that this heat was the engine which drove the creation of new rock: land was eroded by air and water and deposited as layers in the sea; heat then consolidated thesedimentinto stone, and uplifted it into new lands. This theory was dubbed "Plutonist"in contrast to the flood-oriented theory.

As well as combating the Neptunists, he also accepted the growing consensus on the concept ofdeep timefor scientific purposes. Rather than accepting that the earth was no more than a few thousand years old, he maintained that theEarth must be much older,with a history extending indefinitely into the distant past.[24]His main line of argument was that the tremendous displacements and changes he was seeing did not happen in a short period of time by means of catastrophe, but that processes still happening on the Earth in the present day had caused them. As these processes were very gradual, the Earth needed to be ancient, to allow time for the changes. Contemporary investigations had shown that the geologic record required vast time, but no good way of assigning actual years was found for over a century (Rudwick,Bursting the Limits of Time). Hutton's idea of infinite cycles with humans present throughout is quite different from modern geology, with a definite time of formation and directional change through time, but his supporting evidence for the long-term effects of geological processes was valuable in the development of historical geology.

Acceptance of geological theories

[edit]It has been claimed that the prose ofPrinciples of Knowledgewas so obscure that it also impeded the acceptance of Hutton's geological theories.[43]Restatements of his geological ideas (though not his thoughts on evolution) byJohn Playfairin 1802 and thenCharles Lyellin the 1830s popularised the concept of an infinitely repeating cycle, though Lyell tended to dismiss Hutton's views as giving too much credence to catastrophic changes.

Other contributions

[edit]Meteorology

[edit]It was not merely the earth to which Hutton directed his attention. He had long studied the changes of theatmosphere.The same volume in which hisTheory of the Earthappeared contained also aTheory of Rain.He contended that the amount of moisture which the air can retain insolutionincreases with temperature, and, therefore, that on the mixture of two masses of air of different temperatures a portion of the moisture must be condensed and appear in visible form. He investigated the available data regarding rainfall andclimatein different regions of the globe, and came to the conclusion that the rainfall is regulated by thehumidityof the air on the one hand, and mi xing of differentair currentsin the higher atmosphere on the other.

Earth as a living entity

[edit]Hutton taught that biological and geological processes are interlinked.[44]James Lovelock,who developed theGaia hypothesisin the 1970s, cites Hutton as saying that the Earth was asuperorganismand that its proper study should be physiology.[45]Lovelock writes that Hutton's view of the Earth was rejected because of the intensereductionismamong 19th-century scientists.[45]

Evolution

[edit]Hutton also advocated uniformitarianism for living creatures –evolution,ina sense– and even suggestednatural selectionas a possible mechanism affecting them:

- ...if an organised body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be the most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organised bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race. –Investigation of the Principles of Knowledge,volume 2.[42]

Hutton gave the example that where dogs survived through "swiftness of foot and quickness of sight... the most defective in respect of those necessary qualities, would be the most subject to perish, and that those who employed them in greatest perfection... would be those who would remain, to preserve themselves, and to continue the race". Equally, if an acutesense of smellbecame "more necessary to the sustenance of the animal... the same principle [would] change the qualities of the animal, and.. produce a race of well scented hounds, instead of those who catch their prey by swiftness". The same "principle of variation" would influence "every species of plant, whether growing in a forest or a meadow". He came to his ideas as the result of experiments inplantandanimal breeding,some of which he outlined in an unpublished manuscript, theElements of Agriculture.He distinguished betweenheritable variationas the result of breeding, andnon-heritable variationscaused by environmental differences such as soil and climate.[42]

Though he saw his "principle of variation" as explaining the development of varieties, Hutton rejected the idea that evolution might originate species as a "romantic fantasy", according topalaeoclimatologistPaul Pearson.[46]Influenced bydeism,[47]Hutton thought the mechanism allowed species to form varieties better adapted to particular conditions and provided evidence ofbenevolent designin nature. Studies ofCharles Darwin's notebooks have shown that Darwin arrived separately at the idea ofnatural selectionwhich he set out in his 1859 bookOn the Origin of Species,but it has been speculated that he had some half-forgotten memory from his time as a student in Edinburgh of ideas of selection in nature as set out by Hutton, and byWilliam Charles WellsandPatrick Matthewwho had both been associated with the city before publishing their ideas on the topic early in the 19th century.[42]

Works

[edit]- 1785.Abstract of a dissertation read in the Royal Society of Edinburgh, upon the seventh of March, and fourth of April, MDCCLXXXV, Concerning the System of the Earth, Its Duration, and Stability.Edinburgh. 30pp.at Oxford Digital Library.

- 1788.The theory of rain.Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. 1, Part 2, pp. 41–86.

- 1788.Theory of the Earth; or an investigation of the laws observable in the composition, dissolution, and restoration of land upon the Globe.Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. 1, Part 2, pp. 209–304.atInternet Archive.

- 1792.Dissertations on different subjects in natural philosophy.Edinburgh & London: Strahan & Cadell.at Google Books

- 1794.Observations on granite.Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, vol. 3, pp. 77–81.

- 1794.A dissertation upon the philosophy of light, heat, and fire.Edinburgh: Cadell, Junior, Davies.ate-rara (ETH-Bibliothek)

- 1794.An investigation of the principles of knowledge and of the progress of reason, from sense to science and philosophy.Edinburgh: Strahan & Cadell.at(VIRGO) University of Virginia Library)

- 1795.Theory of the Earth; with proofs and illustrations.Edinburgh: Creech. 3 vols.ate-rara (ETH-Bibliothek)

- 1797.Elements of Agriculture.Unpublished manuscript.

- 1899.Theory of the Earth; with proofs and illustrations, vol III,Edited by Sir Archibald Geikie. Geological Society, Burlington House, London.atInternet Archive

Recognition

[edit]

- A street was named after Hutton in theKings Buildingscomplex (a series of science buildings linked toEdinburgh University) in the early 21st century.

- ThepunkbandBad Religionquoted James Hutton with "no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end" in their song "No Control".[48]

- Mount Huttonin theSierra Nevada Mountain Rangeis named after Hutton.

See also

[edit]- Deep history

- James Hutton Institute

- Climate of Scotland

- Geology of Scotland

- Shen Kuo

- Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle,a book byStephen Jay Gouldthat reassesses Hutton's work

References

[edit]- ^Daly, Sean; Agricola, Georgius (10 May 2018).From the Erzgebirge to Potosi: A History of Geology and Mining Since the 1500's.FriesenPress.ISBN978-1-5255-1758-7.

- ^Waterston, Charles D; Macmillan Shearer, A (2006).Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002: Biographical Index(PDF).Vol. I. Edinburgh:The Royal Society of Edinburgh.ISBN978-0-902198-84-5.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 19 September 2015.Retrieved17 July2012.

- ^University of Edinburgh."Millennial Plaques: James Hutton".Hutton's Millennial Plaque, which reads, "In honour of James Hutton 1726–1797 Geologist, chemist, naturalist,father ofmodern geology,alumnusof the University, "is located at the main entrance of theGrant Institute.Archived fromthe originalon 1 November 2007.

- ^abDavid Denby (11 October 2004)."Northern Lights: How modern life emerged from eighteenth-century Edinburgh".The New Yorker.

In 1770, James Hutton, an experimental farmer and the owner of asal ammoniacworks, began poking into the peculiar shapes and textures of theSalisbury Crags,the looming, irregular rock formations inEdinburgh.Hutton noticed something astonishing—fossilizedfish remains embedded in the rock. The remains suggested thatvolcanic activityhad lifted the mass from some depth in the sea. In 1785, he delivered a lecture to theRoyal Society of Edinburgh,which included the remarkable statement that "with respect to human observation, this world has neither a beginning nor an end." The book that he eventually published,Theory of the Earth,helped to establish modern geology.

- ^abM. J. S. Rudwick (15 October 2014).Earth's Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters.University of Chicago Press. pp. 68–70.ISBN978-0-226-20393-5.

- ^abcdAmerican Museum of Natural History(2000)."James Hutton: The Founder of Modern Geology".Earth: Inside and Out.Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.

"The result, therefore, of this physical enquiry", Hutton concluded, "is that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end".

- ^Kenneth L. Taylor (September 2006)."Ages in Chaos: James Hutton and the Discovery of Deep Time".The Historian(abstract).Book reviewofStephen Baxter.ISBN0-7653-1238-7.Retrieved8 April2017.

- ^"James Hutton (1726-1797)".Edinburgh Geological Society.Retrieved29 December2023.

- ^Schuchmann, J.B. (2023).James Hutton's stay in Leiden (1749)(1st ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Leidse Geologische Vereniging. pp. 1–86.ISBN9789090365442.

- ^abcdeDean 1992

- ^"Business and Related Interests".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2011.Retrieved3 August2019.

- ^"Farming and Hutton the Geologist".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2011.Retrieved3 August2019.,Playfair

- ^Campbell, Lewis; Garnett, William (1882).The Life of James Clerk Maxwell.London: Macmillan and Company. p.18.

hutton George Clerk Maxwell.

- ^"Return to Edinburgh".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2012.Retrieved11 April2008.

- ^"Hutton's Contemporaries and The Scottish Enlightenment".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2011.Retrieved3 August2019.

- ^"Williamson's directory for the City of Edinburgh, Canongate, Leith and suburbs".National Library of Scotland.1773–1774. p. 36.Retrieved2 December2017.

- ^"The Forth and Clyde Canal".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2011.Retrieved3 August2019.

- ^abBiographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002(PDF).The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006.ISBN0-902-198-84-X.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 24 January 2013.Retrieved21 November2016.

- ^"James Hutton | Encyclopedia".encyclopedia.

- ^"Settled and Unsettled".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2011.Retrieved3 August2019.

- ^"Theory of the Earth".James Hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 8 September 2012.Retrieved11 April2008.

- ^abcdTheory of the Earthfull text (1788 version)

- ^abConcerning the System of the EarthArchived7 September 2008 at theWayback Machineabstract

- ^abRobert Macfarlane (13 September 2003)."Glimpses into the abyss of time".The Spectator.

Hutton possessed an instinctive ability to reverse physical processes – to read landscapes backwards, as it were. Fingering the white quartz which seamed the grey granite boulders in a Scottish glen, for instance, he understood the confrontation that had once occurred between the two types of rock, and he perceived how, under fantastic pressure, the molten quartz had forced its way into the weaknesses in the mother granite.

- ^"Glen Tilt".Scottish Geology. Archived fromthe originalon 6 May 2020.Retrieved3 May2011.

- ^Stephen J. Gould, page 70, Time's Arrow, Time's Circle, 1987

- ^Scottish Geology – Hutton's Section at Salisbury Crags

Scottish Geology – Hutton's Rock at Salisbury CragsArchived9 August 2018 at theWayback Machine - ^Cliff Ford (1 September 2003)."Hutton's Section at Hoyrood Park".Geos.ed.ac.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 24 June 2011.Retrieved3 May2011.

- ^"Hutton's Unconformity".Isle of ArranHeritage Museum. 2014.Retrieved20 November2017.

- ^"Hutton's Unconformity – Lochranza, Isle of Arran, UK – Places of Geologic Significance on Waymarking".Retrieved20 October2008.

- ^abcdKeith Montgomery (2003)."Siccar Point and Teaching the History of Geology"(PDF).University of Wisconsin.Retrieved26 March2008.

- ^Hugh Rance (1999)."Hutton's unconformities"(PDF).Historical Geology: The Present is the Key to the Past.QCC Press. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 December 2008.Retrieved20 October2008.

- ^"Jedburgh: Hutton's Unconformity".Jedburgh online.Archived fromthe originalon 9 August 2010.

Whilst visiting Allar's Mill on the Jed Water, Hutton was delighted to see horizontal bands of red sandstone lying 'unconformably' on top of near vertical and folded bands of rock.

- ^"Hutton's Journeys to Prove his Theory".James-hutton.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 2 August 2012.Retrieved3 May2011.

- ^"Hutton's Unconformity".Snh.org.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 24 September 2015.Retrieved3 May2011.

- ^John Playfair(1999)."Hutton's Unconformity".Transactions of theRoyal Society of Edinburgh,vol. V, pt. III, 1805, quoted inNatural History,June 1999.Archived fromthe originalon 8 July 2012.

- ^Elizabeth Lincoln Mathieson (13 May 2002)."The Present is the Key to the Past is the Key to the Future".The Geological Society of America. Archived fromthe originalon 9 March 2016.Retrieved28 September2010.

- ^Thomson, Keith (2001)."Vestiges of James Hutton".American Scientist.89(3): 212.doi:10.1511/2001.3.212.Archived fromthe originalon 11 June 2011.

It is ironic that Hutton, the man whose prose style is usually dismissed as unreadable, should have coined one of the most memorable, and indeed lyrical, sentences in all science: "(in geology) we find no vestige of a beginning,—no prospect of an end." In those simple words, Hutton framed a concept that no one had contemplated, that the rocks making up the earth today have not, after all, been here since Creation.

- ^Greg Graffin(1989)."Lyrics, No Control".No Control.

there's no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end (Hutton, 1795)

- ^Theory of the Earth, Volume 1atProject Gutenberg

- ^Theory of the Earth, Volume 2atProject Gutenberg

- ^abcdPearson, Paul N. (October 2003)."In retrospect".Nature.425(6959): 665.Bibcode:2003Natur.425..665P.doi:10.1038/425665a.S2CID161935273.

- ^Geikie, Archibald (1897).The Founders of Geology.London: Macmillan and Company. p.166.

james hutton geology.

- ^Capra, Fritjof (1996). The web of life: a new scientific understanding of living systems. Garden City, N.Y: Anchor Books. p. 23. ISBN0-385-47675-2.cited in"Gaia hypothesis"

- ^abLovelock, James (1979).GAIA – A new look at life on Earth.Oxford University Press. pp. viii, 10.ISBN978-0-19-286030-9.

- ^Connor, Steve (16 October 2003)."The original theory of evolution... were it not for the farmer who came up with it, 60 years before Darwin".The Independent.Retrieved5 February2014.

- ^Dean, Dennis R. (1992).James Hutton and the History of Geology.Cornell University Press. pp.265.ISBN978-0801426667.

James Hutton deist -wikipedia.

- ^Keith Stewart Thomson (May–June 2001). "Vestiges of James Hutton". American Scientist V. 89 #3 p. 212.

Further reading

[edit]- Baxter, Stephen(2003).Ages in Chaos: James Hutton and the Discovery of Deep Time.New York:Tor Books,2004.ISBN0-7653-1238-7.Published in the UK asRevolutions in the Earth: James Hutton and the True Age of the World.London:Weidenfeld & Nicolson.ISBN0-297-82975-0

- Dean, Dennis R. (1992).James Hutton and the history of geology.Ithaca: Cornell University Press.ISBN9780801426667.

- McKirdy, Alan (revised ed. 2022).James Hutton: The Founder of Modern Geology.Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland.ISBN1-9106-8244-6.

- Perman, Ray (2022).James Hutton: The Genius of Time.Edinburgh: Birlinn.ISBN1-7802-7785-7.

- Playfair, John (1822)."Biographical Account of the late James Hutton, M.D.".The Works of John Playfair, Esq.Vol. IV. Edinburgh: Constable.

- Repcheck, Jack (2003).The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth's Antiquity.London andCambridge, Massachusetts:Simon & Schuster.ISBN0-7432-3189-9(UK),ISBN0-7382-0692-X(US)

External links

[edit]- James-Hutton.org,links toJames Hutton – The ManandThe James Hutton Trail.

- James Hutton and Uniformitarianism(scroll down)

- James Hutton's memorial in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh

- First Publication of Theory of the Earth

- Accessible Historical Perspective on James Huttonat theWayback Machine(archived 8 May 2006)

- Gould, Stephen Jay."Justice Scalia's Misunderstanding".B16: The History of Life: Source Book.pp.137,138,139,140.Archived fromthe originalon 8 June 2019.Retrieved17 July2014.

- Works by James HuttonatProject Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Huttonat theInternet Archive

- O'Connor, John J.;Robertson, Edmund F.,"James Hutton",MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive,University of St Andrews

- Digitized volumes at theLinda Hall Library:

- Hutton's (1788),"Theory of the Earth."Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh,Vol. 1, no. 20.

- Hutton's (1795–1899),Theory of the earth, with proofs and illustrations, 3 vols.

- John Playfair (1802),Illustrations of the Huttonian theory of the Earth

- John Playfair (1815),Explication de Playfair sur la théorie de la terre par Hutton(French)

- 1726 births

- 1797 deaths

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Burials at Greyfriars Kirkyard

- Charles Darwin

- British deists

- Leiden University alumni

- Proto-evolutionary biologists

- People associated with the Scottish Borders

- Scientists from Edinburgh

- People educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh

- Founder fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Scottish agronomists

- Scottish businesspeople

- Members of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh

- Scottish geologists

- Scottish meteorologists

- University of Paris alumni

- 18th-century Scottish medical doctors

- Scottish biologists

- 18th-century Scottish farmers

- People of the Scottish Enlightenment

- Enlightenment scientists

- 18th-century British scientists

- Scottish agriculturalists

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- 18th-century British geologists